Jesuit Mission and the Globalization of Knowledge of the Americas: Florian Paucke’s Hin und Her in the Province of ‘Paraquaria’ During the Eighteenth Century

I am grateful to my colleagues José Carlos Rovira, Claudia Comes and Eva Valero Juan for their kind invitation to take part in the conference “América y los jesuitas expulsos” (Centro de Estudios Literarios Iberoamericanos Mario Benedetti, Universidad de Alicante, September 2015), at which I presented a first version of this article. In addition, I thank Sina Rauschenbach, Roberto Aedo, Enrique Corredera Nilsson and Settimio Presutto for their critical reading and bibliographic recommendations. This article was translated by David Sánchez Cano.

Rolando Carrasco M., Universität Osnabrück

Abstract: This article addresses the early globalization phase of the Jesuit Order in America through Florian Paucke’s work Hin und Her.32 Special attention is given to the analysis of the field of tensions underlying the proto-globalization processes of the Spanish empire and the frontier mission, for which three narrative components are considered: ‘Paraquaria’33 and the cartography of the spiritual ‘mission’; a reflection on intercultural stereotypes (indigenous, Spaniards and Germans); and the deconstruction of the autonomist myth of Nicolás I, King of Paraguay.

In current research, the history of globalization and its accelerated impact on the economic, political, sociological, juridical and technological sciences, among others, demonstrates the multidisciplinary resonances that this category has attained—not solely in the scholarly field, but also in everyday speech. Thus, the complexity of the components that converge in the conceptualization of globalization, as well as the dimensions and the respective phases of its evolution, have been the objects of diverse theoretical approaches. This has been particularly true since global transformations accelerated after the end of the Cold War. Multi-dimensional and international changes in the market economy, cosmopolitism and technological connectivity intertwined with the reshaping of a new global village (cf. Fäßler 2007; Osterhammel 2003, 2017; Conrad 2013). Amid the coordinates of this global history, the necessity of re-thinking this category in its apparent unity as a historical phenomenon of the West opens up the question of what Romanist Ottmar Ette terms the ‘archaeology of globality’:

For speech about an archaeology of globality implies a singular, but nevertheless does not define whether an ur- or early history are supposed to be analyzed as a pre-history of globality, or if the object of such archaeology may also include earlier forms of the former which are not part of a pre-history, but constitute an essential element of globality in its temporal and spatial transition. To what extent we will wish to attribute a spatial and historic phenomenon (and our knowledge about it) to a history of globality or, alternatively, “only” to its pre-history, will depend decisively on how globality is defined and exactly what phenomena we are trying to investigate. How could we, then, conceptualize globality in the plural? (Ette 2010, p. 22)

This question about the distinction already drawn by sociologist Ulrich Beck between ‘globality’ and ‘globalism’ (the ideology of the world market) takes us back in time to the early modern age of the sixteenth century (Beck 1997). As an early phase—or ‘proto-globalization’,34 to employ Fäßler’s term—it is characterized by the colonial expansion of the Iberian powers, modern nautical technologies, the search for overseas routes with the ‘Asian invention’ of America (Dussel 1994) and the Catholic missionary project in the two Indies; in short, by components that contributed to the political-spiritual, economic, cartographic and anthropological redesigning of new spaces of interaction in the Atlantic world, with the ensuing debate on and redefinition of European hegemony (Guérin 1992). For Ette, the distinction between four phases of accelerated globalization (Ette 2010, pp. 24–25) and in particular his interest in the analysis of the early philosophical reflections by De Pauw, Forster, Raynal and Humboldt on the Americas and Europe during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, delineate an archaeology of globality open to a permanent revision of its actors, dynamics, and modes of representation and reflection, within the framework of the hetero-discursivities that moved through this global Aufklärung [‘Enlightenment’] (D’Aprile 2016).

One of the distinctive components of this process of accelerated proto-globalization was the expansion of the Catholic church to the four corners of the world, especially by the Jesuit Order (cf. Koschorke 2012, pp. 4–5; van der Heyden 2012). Ever since its foundation in 1540 by Saint Ignatius of Loyola, the Jesuit Church’s structures and transcontinental networks of communication—true to their pastoral motto ‘urbi et orbi’—have made them excellent examples to be studied as a globalizing model of multidimensional (scientific, historical, economic, philosophical, etc.) and international knowledge,35 born of the missionary norms of the Society of Jesus (apostolic mobility, human adaptation and advancement of indigenous peoples) and its intercultural experiences in India, Asia and the New World (Banchoff 2016). Within this broad chapter of the Jesuit spiritual conquest, this essay aspires to determine the specific modalities of representation of and reflection on Spanish colonialism in the Americas during the eighteenth century, examining in this early phase of globalization German-Silesian Jesuit Florian Paucke’s contribution, known as Hin und Her. My objective is to problematize, from the evangelist experience and narrative memoire of this expelled traveler, some of the issues that underlie this proto-history of globalization and the utopian Christian-social project that the Jesuits represented in the New World.

Hin und Her:

memoire and itinerary of an expelled traveller

The text by Paucke known as Hin und Her [‘There and Here’] constitutes one of the most representative chronicles of the frontier ministry carried out by the Ibero-American missions in the Chaco region. Written in German, the manuscript is preserved in the Cistercian monastery in Zwettl (Austria) and was published in a complete edition in German in 1959. The work offers a narrative and visual portrayal—in over 1000 pages, 104 watercolors integrated into the text, and ten very large scrolls—of diverse aspects of the life and customs of indigenous peoples, of a missionary experience lasting 21 years in the north of the present-day Argentinian province of Santa Fe, and of the rich geographic and natural environment of the region (Furlong 1973; Binková 2001). Paucke’s legacy complements that of the Bohemian Jesuit Martin Dobrizhoffer, who after returning to Austria composed his Historia de Abiponibus (1772–1775) in Latin. Dobrizhoffer’s Historia was soon translated into German and published in Vienna (Dobrizhoffer 1784), adding to the corpus of literature on the expulsion of the Central-European Jesuits from the interior frontier of South America (Meier 2007a).36 In Hans Jürgen Lüsebrink’s opinion, the chronicles by the expelled missionaries from Central Europe who had a Germanic language and culture, such as Johann Jakob Baegert (missionary in the southern California peninsula) and Martin Dobrizhoffer, testify to a twofold effort: on the one hand, “to understand the alterity of the values and forms of behavior of the indigenous peoples” (Lüsebrink 2007, pp. 384–385); and on the other, to furnish a counter-discourse, since they sought—just like the expelled criollos—to correct mistaken conceptions in Europe regarding the reality of the New World (Lüsebrink 2014). Such intentions can be identified in Paucke’s work in those that impact on a specific perspective of his narrative of the political-spiritual conquest of the New World.

The adverbial use in the manuscript’s title Hin und Her indicates, according to Edmundo Wernicke,37 less a static understanding and identification of the places visited by the traveler, ‘but rather the emotions encountered in going there (hin) and returning (her)’. The pendularity of this pathos, as expressed by Paucke—‘hin’ (there, sweet and pleased) and ‘her’ (here, bitter and sorrowful) —corresponds to his trans-Atlantic itinerary (via Olmütz [Olomouc], Malaga, Lisbon, Buenos Aires, Cordoba), with a clear focus on his missionary experience in Santa Fe and San Javier until the enacting of the decree of expulsion in 1767, which obliged him to retrace his maritime journey from Montevideo to Spain and ultimately Germany.38 The compositional complexity of Paucke’s text (autobiography, spiritual, ethnographic, linguistic chronicle and natural history) for the Chaco region is lent coherence by the unifying thread of his ‘memory’ (Zanetti 2013) in the ‘Province of Paraquaria’:

No one should be surprised that in the 59th year of my life, after suffering the heat of the sun and the exhaustion of my travels, after 21 years of laboring in Paraguay without ever having, before I went there, at least briefly noted something down on paper, I perceive a considerable loss of memory. Instead, I marvel that I have preserved in my memory all the things I write about. If I had cherished the hope of ever seeing Europe again, then I would not have so carelessly let my notation quill dry up, for my will was to remain eternally with my Indians. (HH, V2/P6/C9, p. 730)

Despite the enforcement of the punishment of expulsion, Paucke’s narrative memory is synonymous with the recording of his evangelistic experience among the indigenous Mocovís in the Chaco region and his re-encounter with Europe. The narrative self-referentiality of this subject, whose Hin und Her embraces the autobiographical pathos, is distinguished not merely by the pendularity of his emotions, but also of his own understanding. In other words, he has a reflective consciousness, whose act of writing revives the successes as well as the tragedies of his individual—and the Order’s collective—missionary experience in the Province of Paraquaria. At the same time, I aim to place his historical revisionism, as regards the colonial project in the Americas. For this reason, it is worthwhile to determine how his narrative stages the framework of submerged tensions in this process of the proto-globalization of the colonial empire and the frontier mission of the Jesuits later expelled from Ibero-America.

‘Paraquaria’, frontier mission and trans-continental communication networks

From the dawn of globalization’s first phase, the exploration of the American territory and the concurrent creation of the ‘frontier’ were part of a process of inventing an unknown alterity. The traditional paradigm of civilization/barbarism operated as an interpretative matrix during the early representations and interpretations in the colonial textual and visual heritage, as an expression of the Europeanizing and ethnocentric authority of the early modern age. Within this context, the geostrategic significance of northern Mexico (due to the Chichimeca War and the exploitation of the silver mines) or the Chaco region (due to its importance in livestock supply for Peru and as a border against Portuguese ‘bandeirantes’), for example, already demonstrated in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the frontier conflicts on the borders of the Spanish empire in the Americas and the active role played by the religious Orders.39

In Manuel Lucena Giraldo’s opinion, the changes triggered around 1740 by ‘geographic territorial consciousness’ (Lucena Giraldo 1996, p. 268) led the Bourbon state to impose greater social, political and economic control of the American space at the southern margins of its empire. These measures affected the so-called ‘Jesuit state’ in Paraguay through the Order’s expulsion from Portugal (1759), France (1763), Spain (1767), Naples, Parma and Malta, as well as from the overseas colonies. Despite anti-Jesuit propaganda in Europe and America, the establishment of missions and their intervention in the ‘parliaments’ or ‘peace councils’ contributed to a ‘sphere of consensus’ that regulated the intercultural friction between Spaniards and indigenous peoples in the frontier space. According to Guillaume Boccara, one should accentuate a critical perspective that conceptualizes the frontier zones as dynamic and dialogical spaces, and as “an immense ‘laboratory’ for the study of the processes of mestizaje and for the creation of new historical subjects” (quoted in Battcock 2004, p. 2). This latter perspective certainly breaks with the apparent geometric linearity of the space of frontier confrontation that for centuries justified the expansionist policies of the Spanish and Portuguese crowns in the human (‘savage’, ‘cannibal’, ‘pagan’ Indians) and natural (inaccessible jungle, gold, rivers, mountains) landscapes of the New World.40 On the contrary, it means the ‘conjugation of cultural heritages’ (in Gruzinski’s terms) that allow the frontier to be ‘porous, permeable and flexible’. The constitution of the Jesuit utopia of the ‘reductions’ alerts us to the efforts put into the conquest of this fluid territorial dimension of South America and of the mobility of diverse indigenous groups in the so-called Province of Paraquaria.

As is well known, the projection of utopian ideals in the so-called pueblos de indios or ‘reductions’ has intensely captivated the attention of scholars, in particular of the ‘doctrines’ of Jesuit missions in Paraguay (cf. Cro 1990; Armani 1996), which have been regarded as a “materialization of the Augustinian ‘Civitas Dei’ on earth, given the strongly theocratic character that the Jesuits imposed on these civic groups in the reductions in Paraguay” (Rodríguez de Ceballos, p. 162).41 The debate in the eighteenth century was marked on the one hand by their defense by Ludovico Muratori and José Manuel Peramás,42 and on the other by their negative evaluation by authors such as Ibañez de Echevarri, Thomas Raynal and Cornelius de Pauw.43

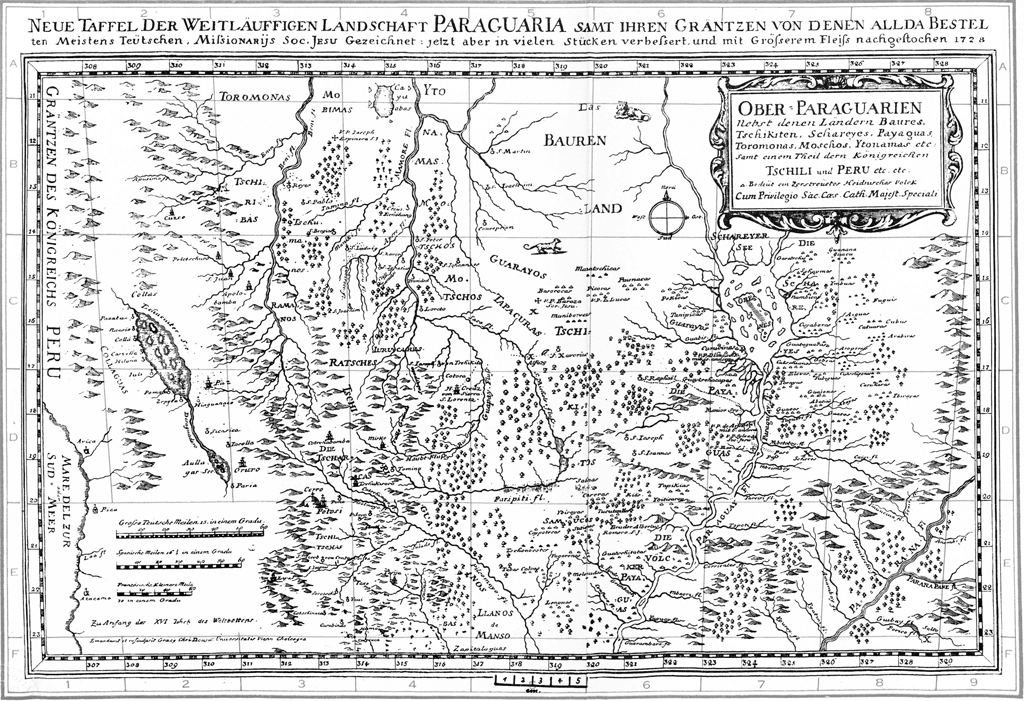

The circulation of geographic knowledge of the Chaco frontier can already be discerned in Martin Dobrizhoffer’s Historia de Abiponibus, which mapped the immense extension of that region in South America, from Brazil to Peru and Chile, and from the southern delta of the Río de la Plata to the northern Amazon area (fig. 1).

Paucke’s work likewise focuses on the so-called province of Paraquaria. The geographical immensity and the identification of unknown lands—i.e., beyond the reductions (HH, V2/P3/C3, p. 146)—demonstrate the will to inform and rectify previous letters and to transmit ‘true’ knowledge of the imperial Spanish-Portuguese frontier and of spiritual conquests, thanks to the reduction of San Javier. For this reason, the categorical visual certification of Paucke’s knowledge is not surprising:

I draw solely on what I have seen with my eyes and trodden with my feet in the maps made of America. Oh, how mistaken the far-away cartographers have been! I will report later on how we Paraquarian missionaries, when we were expelled from America by order of the king of Spain, were commanded to draw up a genuine iconographic map of the Grand Chaco, where we have worked, one for the king, the second for the viceroy in Lima, and the third for the governor of Buenos Aires. If one compares these maps against the ones made beforehand, then one will discover how erroneous they were. (HH, V2/P3/C3, p. 458)

Paucke’s missionary-exploratory work and his criticism of the ‘Geometers und Ichnographisten’ [cartographers] of the American realms confirms the lack of concurrence between the political colonial territory and the spiritual dominion (Fernández Bravo 2014). This acquires greater relevance when the discourse enumerates the diversity of ‘Indian nations’ in the regions of Chaco, Mocovíes, Abipones, Tobas, Mataguayos, etc. (HH,V2/P3/C3, p. 456), thus visualizing the multiethnic, cultural and especially linguistic condition in the space of this mission. The corrective function of Paucke’s narrative refutes the supposed unity of language, customs, nature and physiognomy of the American indigene (HH, V2/P3/ C1, p. 447). At the same time, he argues for the indigenous people’s capacity of understanding and ability (HH, V2/P3/C17, pp. 562–575). Ultimately, the Jesuit intervention not only confirms that in these Spanish possessions “one finds more differences in nations and languages than in the remaining three parts of the world” (HH, V2/P3/C3, p. 457). Moreover, it underlines the preeminence and recognition of the service of the indigenous peoples and ‘soldiers of God’ for the colonial project, since “the king of Spain alone possesses many more countries than all the princes and kings of Europe” (HH, V2/P3/C3, p. 146).

However, it must be emphasized that the cartographic, natural and ethnographic investigation of the vast American realm undertaken by the Jesuits acquired special relevance in Europe thanks to the knowledge transfer facilitated by their networks of transcontinental communication during this first phase of globalization. This component deserves to be highlighted, thanks to the publication of the cultural ethnographic periodical Neue Welt-Bott [‘New World Messenger’], edited by the Jesuit Joseph Stöcklein between 1725 and 1761, and subtitled, “Letters, Writings, and Travel Descriptions, Most of them from the Missionariis Societatis Jesu from Both Indies and Other Overseas Lands which since 1692 Until this Year Have Arrived in Europe (…).” This collection of letters—the majority of which originated from the overseas missions in the Orient—also included the narrative and cartographic production of the Jesuits from South America (Furlong 1936, Vol. I, p. 49). A representative example is the map and report44 on Paraquaria that appeared in the 1730 volume of Neue Welt-Bott (fig. 2).

Galaxis Borja González has demonstrated the significant role the German press played in the diffusion and reception of literature by the Jesuits in America. In particular, Dobrizhoffer’s abovementioned Historia de Abiponibus (1784) and other Jesuit writings in German contributed to the emergence of a ‘global awareness’ without the need of translators or mediators. They also played an important role in the construction of an imagined political community in eighteenth-century Germany:

In this manner, the Jesuit missionary narratives are inserted into the efforts of German scholarly elites to define an early national identity, constructed on the idea—or in reality on the desire—of possessing a common language and of sharing a determined canon of virtues, attitudes, and values. This positive and inter-confessional handling of the notions of “the German” was possibly the reason why the Enlightenment authors of the second half of the eighteenth century were interested in the missionary texts and referred to them when approaching […] the issue of the nation. (Borja González 2012, p. 188)45

Borja González’s proposal seems particularly interesting within the context of an accelerated proto-globalization, since it highlights the circulation and reception of sources (in Latin or German) written by the Jesuits during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In contrast to the ‘proto-national’ identity awareness of the Jesuit criollos expelled from Mexico or Peru, the narratives of central-European Jesuits allow us to critically examine the folds of this process of early globalization by means of two questions: 1) is it possible to postulate possible divergences in the missionary perspectives within the Jesuit Order itself during its eighteenth-century colonial project in the Americas?; and 2) does an identity proto-consciousness exist in Paucke’s work, based on the attitudes, values and virtues that define him as a European subject? The following shall address these two questions.

Archetypical constructions in Paraquaria: a Prussian Jesuit among Spaniards

As mentioned above, in the context of the foundational postulates of the Jesuit Order, ‘travel’ and ‘mission’ are almost synonymous. The term ‘mission’ expresses the aspirations of universality and of the knowledge and conversion of ‘pagan’ peoples, but also specifically the truncated (by expulsion) project of Jesuit evangelism in the deserts, jungles and plains of Spanish America. Hin und Her is not only marked by the missionary vow of preaching the faith in this phase of proto-globalization, but also by the loss of his own patriotic identity in the Old World:

As everyone must know, we Jesuits, in particular those from German lands, who by the zealous soliciting of our superiors succeed in being allowed to travel to these pagan lands, go there voluntarily and completely perish for our fatherland. If I have left out many things that in certain passages have escaped my weak memory, then if they return to me I will, as long as God gives me life, add an appendix at the end. (HH, V2/P6/C9, pp. 730 –731)

In sharp contrast, the discourse of the expelled criollos Jesuits—such as Francisco Javier Clavijero, Juan Ignacio Molina and Juan de Velasco—was placed in the context of the debate on the New World (Gerbi 1982). They identified themselves with the interrupted criollo ‘homeland’ that formed part of Peruvian Jesuit Juan Pablo de Viscardo y Guzmán’s idea of independence (Pinedo 2010; Hachim 2008).

Paucke seems to experience the symptoms of a double crisis during his return to Europe: on one hand, the crisis of the foundational and corporative postulates of the subject who obeys the punishment of expulsion and suppression of the Order (Fernández Arrillaga 2013, p. 16); on the other hand, that of his own patriotic identification with the central-European countries as former subjects of the Holy Roman Empire. No less relevant in Paucke’s ‘memory’ is his self-representation as a globalized passeur, relativizing the prejudices and civilizatory preponderance of one nation over others:

I will admit that inclinations, habits, and customs are not the same all over the world and I have experienced this myself. But to believe that all the people in a country are subject to their natural inclinations, to the enjoyment of their passions, and permit all their desires, is a prejudice. I have travelled around the greatest part of our Europe, except for the realms in the far north and in the east near Turkey, and have experienced and known all of those peoples who are more moral than others. Nevertheless, although the Germans are praised above others in the sciences, arts, and skills, my experience has convinced me that none of these are lacking in other lands (…). I will continue to speak from my experience and dispassionately report the truth. (HH, V1/P1/C1, p. 107)

Paucke’s movements blur the binary opposition between civilization/barbarism by means of distancing (‘expulsion’) as an instrument of knowledge (Fernández Bravo 2014, p. 178). From the beginning of Hin und Her, Paucke advocates a broad knowledge of the New World, emphasizing the archetypical and civilizatory traits of the ‘Germans’ (scientific knowledge, arts, technology) in comparison to Spaniards and indigenous peoples. One should recall that this reference to ‘Germans’ and to the loss of a ‘patriotic’ sentiment in Paucke is expressed in the age of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation—not from the politicalnational map of the twentieth century—and contains the underlying question regarding the identity of those Jesuits from Bohemia, Moravia, Croatia, Silesia, Hungary, Austria and the Palatinate.46 This is a topic of enormous complexity, if one considers that the geopolitical, linguistic and cultural landscapes of these central-European states already encompassed a heterogeneous space whose ethnic, linguistic and national boundaries were for centuries experiencing transformation and redefinition.

This complicates the debate on the imagological, ethnographic and cultural components inscribed in the early reflection on (inter)national stereotypes in Enlightenment discourse.47 During the first half of the eighteenth century:

… the double condition of the Habsburgs as emperors of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation and Kings of Austria, Hungary, Croatia, and Bohemia, meant that a large share of Jesuits belonging to German monasteries were at the same time subjects of two crowns: the imperial and the Austrian. (Borja González 2012, p. 186, note 37)

It can be supposed that this inner polarity for a member of the Jesuit provinces of Silesia (Paucke) or Bohemia (Dobrizhoffer) affected the construction of a differentiated narrative perspective in relation to the imperial program of the Spanish crown in the Americas (Valle 2009, note 22; Nebel (2007). Czech scholar Zdeněk Kalista has highlighted how in comparison to their Spanish companions in the Order, Jesuit missionaries from the province of Bohemia “could not believe themselves owners of the colonies in New Spain in a sense similar to the conception of the immediate subjects of the Spanish king” (Kalista 1968, p. 156) and condemned the methods, the treatment of indigenous peoples, and the colonial systems of both the Spanish and the Portuguese (Kalista 1968, pp. 156–157). Paucke offers a clear counterpoint to any presumed heterogeneity of perspectives within the Jesuit Order.

Firstly, his representation of the practical skills of the exemplary industry of the Catholic world, thanks to the ‘gift of works and trades’ (HH, V2/P3/C17, p. 568),48 was a virtue that distinguished him to the indigenous people and contributed to the acculturative and productive achievements resulting from the reduction. This is expressed in the comment made by the Austrian missionary José Brigniel:

He soon understood me, returned to his room, and said: ‘Yes, my God! This is a powerful miracle, God bestow on this Mestre de Camp sufficient energies; he is a Prussian (he said this because I come from Lower Silesia) and makes the impossible possible, like his king’. (HH, V2/P3/C17, p. 569)

In addition to strengthening Paucke’s virtues and attitudes, the praise of his miraculous action—convincing the young indigenous men to undertake manual work in the reduction—openly contradicts the colonial prejudices of an alleged lack of intelligence, reason and ability for manual production among the indigenous peoples. In his opinion, “solely the absence and dearth of all instruction and doctrine lies at the fault of this” (HH, V2/P3/C17, p. 562). Paucke ultimately deconstructs the entire history of European civilization: “And if the Europeans had been raised with neither doctrine nor education, without the opportunity of knowing anything, in forests, among peoples of equal ignorance, Europe would be an India just like America” (HH, V2/P3/C17, p. 573).

Secondly, no less revealing is the negative stereotyping of the Spaniard (whether European or American) in the space of the mission:

This occurs in those new peoples: if the missionary can do something, if he is skilled and determined to do such things, then the Indians learn what they see; if he is not, then they remain dullards. For who else could they learn from? The Spaniards themselves are hardly eager to learn a trade, everything is only commerce. They regard practicing a trade the most contemptible activity. One will not find any American Spaniards who are tailors, shoemakers, carpenters, or suchlike, all of these trades, and many others, are practiced by their slaves and mulattos. (HH, V2/P3/C17, pp. 571–572)

Paucke here emphasizes the intercultural conflict between the Spanish criollo secular, the clerical and the indigenous worlds in the reductions, counterposing the advancements of Christianization—such as the case of chief Aletín and the defense of the reduction of San Javier (HH, V1/P2/C1, p. 268)—against the disgrace of those ‘dissolute Spaniards’, that ‘vulgar rabble’ whose sole aims were commerce and profit, and the slave exploitation of the indigenous peoples. He rejects the accusations that “the Jesuits, as men greedy for possessions and gold, sought to make Paraquaria their own kingdom” (HH, V2/P3/C18, p. 575), and enumerates the warrior services (provided by the missions against the enemies of the Spaniards) and the tributes paid by the Indians to the crown. Paucke underlines “the conspiracy engendered in the court against the missions” in the province of Paraquaria (HH, V2/P3/C20, p. 603),49 and rejects any accusation of insurrection orchestrated by indigenous peoples and Jesuits against the colonial regime.

An Indian king in the Republic of Paraguay: deconstructing an imagined global fiction

Finally, within the context of those Jesuit travelers and their contribution to a universal ‘geography of knowledge’ (Harris 1999), the informative collections of the Order and the printing of their letters, news reports and travel descriptions permits the consideration of their counter-discursive character in regards to the anti-Jesuit propaganda of the eighteenth century. The texts by Dobrizhoffer, Peramas and Paucke not only aimed to establish and rectify the imperial discourse on the frontier, but also to oppose the libels and defamatory texts against the Society.50 They strove to deconstruct the fictional global imagining of the Jesuit state in Paraguay, disseminated in the press in the Netherlands, France, Germany, Italy and Spain, such as in the case of the History of Nicholas I, King of Paraguay and Emperor of the Mamelukes. Paucke states:

Although everything was glorious and peaceful in our new missions, there was no peace and no tranquility in the old and large missions due to the persecution they suffered at the hands of the Spaniards and Portuguese. They wanted to completely exterminate all the missionaries. The persecution had already been carried out for more than ten years with the greatest zeal. A variety of reports came from Portugal and Spain that more and more claimed that the Jesuits had a separate kingdom in Paraguay and had elected a new king, whose name was Nicholas I. (HH, V1/P4/C10, p. 373)

The impact of this libel (widely translated from French into German and Spanish) from 1755 about ‘Nicolas I’,51 and its representations of the ambitious ‘delinquent’ Nicolás Roubiouni is of enormous interest. Born in Andalucía, this clever libertine schemed his way into the Jesuit Order and obtained permission to travel to the Americas, learned an indigenous language and fomented the indigenous rebellion against the Spanish-Portuguese domination. His imaginary kingdom in Paraquaria rejected the power of the absolutist state and created the space for the realization of the autonomist aspirations of indigenous peoples, black slaves, mestizos and ‘barefoot’ subjects (thieves, murderers). In a relevant chapter of his work (“Of the pseudo king Nicholas”: HH, V1/P1/C6, pp. 167–178), Paucke not only denies the existence of this monarch52 but also categorically rejects this vision of the reductions as regimes that are temporally autonomous, as claimed by defamatory propaganda. For Félix Becker, the myth of Nicholas I can be inscribed in the framework of accusations of a Jesuit plot against the Treaty of Madrid (1750) between the Spanish and Portuguese crowns. It required Spain to cede the territories of seven reductions from the province of Paraguay, which triggered the armed opposition of the indigenous peoples and the alleged leadership of the Jesuits in 1754.53

In spite of this historical rectification and of the extensive analysis of sources to date, there exists little critical attention towards the configuration and circulation of these fictional identities in the space of the frontier and their impact on Paucke’s narrative. In particular, in addition to the supposed figure of Nicholas, the savage and rebellious condition of the Indian, the African and of the troupe of mestizos that made up this new overseas power was repeatedly emphasized. A notable example is that Nicholas I was reportedly the emperor of the ‘Mamelukes’, a name originally designating a lineage of warrior slaves in the Middle East, which in Brazil was applied to the mestizo population and the Spanish hunting of indigenous peoples in the Jesuit reductions. In this invented human geography indigenous and mestizo resistance against the troops of Spain and Portugal completely obscures the advances of the angelical project of Jesuits such as Paucke. In this manner, king Nicholas’ ambition for power, arising from the European fantasy of an imaginary dissidence within the colonial project of the Spanish-Portuguese empire, exposes one of the components that transcends the phases of early globalization: the struggle for self-determination and independence of indigenous peoples in the colonial and post-colonial Americas.

Conclusion

The phenomenon of the Christian mission’s proto-globalization in the province of Paraquaria allows us to recognize the significance of sources like Paucke’s Hin und Her, which together with Dobrizhoffer’s Historia de Abiponibus represents a chapter from the central-European spiritual memory of South America. In his dimension as a global player, Paucke’s narrative not only distinguishes him by its efforts to appreciate American alterity, but also by his clearly counter-discursive component that seeks to rectify the epistemological racism of Spanish colonialism, as well as to contest the circumstances and the reasons for the forced expulsion of the Order. From such a perspective, Hin und Her immerses the field of underlying tensions in the pathos of the Indian missionary experience, as the triumph and loss of the individual and collective identity memory of the Jesuits.

One can distinguish in Paucke’s narrative the enunciation of a reflective awareness in relation to three distinct fields within the dynamics of globalization. Firstly, his writings on Paraquaria allow us to analyze not only his rectifying vision of the territorial and spiritual cartography of the Americas, but also to identify the possible impact of this mission on the transcontinental communication networks of the Jesuit press in the eighteenth century, and the formation of a German national proto-identity. Secondly, Paucke elaborates and puts into circulation an assortment of intercultural stereotypes that counter the prestigious and exemplary industry of the Catholic world, and the achievements of the mission against the vices of Spanish commerce and the colonial interests of a Habsburg monarchy, which for Central-European Jesuits was a double monarchy: imperial and Austrian. Thirdly, we can acknowledge his fruitless efforts to deconstruct, in addition to the historical circumstances of the expulsion, the autonomist and libertine imagination (Nicholas I) of anti-Jesuit propaganda in Europe. On the whole then, these are elements that I believe strengthen the reflective and corrective awareness of Paucke’s work, as a result of the lens of a revisionist (even skeptical) perspective of his own European history and of the ‘civilizatory’ project of the modern age in the so-called era of Enlightenment.

Abbreviated References

HH = Paucke, P. Florian (1959): Zwettler-Codex 420 von P. Florian Paucke S.J. Hin und Her. Hin süsse, und vergnügt, Her bitter und betrübt (…). 2 Vols, Becker-Donner, Etta / Otruba, Gustav (Eds.). Wien: Wilhelm Braumuller. References will be given in the format (HH, V?/P?/C?, p. ?) in which V indicates the Volume number, P is the Part number and C is the Chapter number, followed by the page number/s.

Bibliography

Armani, Alberto (1996): Ciudad de dios y ciudad del sol: el “Estado” jesuita de los guaraníes (1609–1768). México: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Banchoff, Thomas et al. (Eds.) (2016): The Jesuits and Globalization. Historical Legacies and Contemporary Challenges. Washington: Georgetown University Press.

Battcock, Clementina et al. (2004): “Frontera y poder: milicias y misiones en la jurisdicción de Santa Fe de la Vera Cruz, 1700–1780. Algunas reflexiones”. In: Cuicuilco. Revista de Ciencias Antropológicas 11, No. 30, pp. 1–22.

Beck, Ulrich (1997): Was ist Globalisierung? Irrtümer des Globalismus—Antworten auf Globalisierung. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

Becker, Félix (1987): Un mito jesuítico Nicolás I Rey del Paraguay. Aportaciones al estudio del ocaso del poderío de la Compañía de Jesús en el siglo XVIII. Asunción: C. Schauman.

Binková, Simona (2001): “Las obras pictóricas de los PP. Florián Paucke e Ignacio Tirsch: intento de una comparación”. In: Manfred Tietz / Dietrich Briesemeister (Eds.): Los jesuitas españoles expulsos: su imagen y su contribución al saber sobre el mundo hispánico en la Europa del siglo XVIII. Madrid, Frankfurt: Iberoamericana / Vervuert, pp. 189–206.

Borja González, Galaxis (2011): Jesuitische Berichterstattung über die Neue Welt: Zur Veröffentlichungs-, Verbreitungs-und Rezeptionsgeschichte jesuitischer Americana auf dem deutschen Buchmarkt im Zeitalter der Aufklärung. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Borja González, Galaxis (2012): “Las narrativas misioneras y la emergencia de una conciencia-mundo en los impresos jesuíticos alemanes en el siglo XVIII”. In: Procesos. Revista Ecuatoriana de Historia, No. 36, pp. 169–192.

Conrad, Sebastian (2013): Globalgeschichte. Eine Einführung. München: C.H.Beck.

Cro, Stelio (1990): “Las reducciones jesuíticas en la encrucijada de dos utopías. Las utopías en el mundo hispánico”. In: Actas del coloquio celebrado en la Casa Velásquez. Madrid: Casa de Velásquez / Universidad Complutense, pp. 41–56.

D’Aprile, Iwan-Michelangelo (2016): “Aufklärung global-globale Aufklärungen (Das achtzehnte Jahrhundert—Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gesellschaft für die Erforschung des achtzehnten Jahrhunderts)”. In: Achtzehnte Jahrhundert 40, No. 2, pp. 153–308.

Del Valle, Ivonne (2009). Escribiendo desde los márgenes. Colonialismo y jesuitas en el siglo XVIII. México: Siglo XXI.

Dobrizhoffer, Martin (1784): Historia de abiponibus equestri bellicosaque paraquariae natione: locupletata copiosis barbararum gentium, urbium (…). Vienna: Typis Josephi Nob. di Kurzbek.

Dussel, Enrique (1994): “De la ‘invención’ al ‘descubrimiento’ del Nuevo Mundo”. In: El encubrimiento del otro. Hacia el origen del mito de la modernidad. Quito: Abya Yala, pp. 31–47.

Ette, Ottmar (2010): “Arqueología de la globalización. La reflexión europea de dos fases de globalización acelerada en Cornelius de Pauw, Georg Forster, Guillaume Thomas Raynal y Alexander von Humboldt”. In: Sagredo, Rafael (Ed.): Ciencia-Mundo. Orden republicano, arte y nación en América. Santiago: Editorial Universitaria-Centro de investigaciones Diego Barros Arana de la DIBAM, pp. 21–66.

Fäßler, Peter E. (2007): Globalisierung: ein historisches Kompendium. Köln: Böhlau.

Fernández Arrillaga, Inmaculada (2013): Tiempo que pasa, verdad que huye. Crónicas inéditas de jesuitas expulsados por Carlos III (1767–1815). Alicante: Publicaciones Universidad de Alicante.

Fernández Bravo, Alvaro (2014): “Paracuaria, ¿territorio imaginario o contestación simbólica? Jurisdicción espiritual y conocimiento material en las obras de Martin Dobrizhoffer y Florian Paucke”. In: Sierra, Marta (Coord.): Geografías imaginarias: espacios de resistencia y crisis en América Latina. Santiago: Editorial Cuarto Propio, pp. 167–190.

Fernández Herrero, Beatriz (1992): La utopía de América. Barcelona: Anthropos.

Friedrich, Markus (2011): Der lange Arm Roms? Globale Verwaltung und Kommunikation im Jesuitenorden; 1540–1773. Frankfurt am Main: Campus-Verlag.

Furlong, Guillermo (1936): Cartografía jesuítica del Río de la Plata. 2 Vols. Buenos Aires: Talleres Casa Jacobo Peuser.

Furlong, Guillermo (1973): Iconografía colonial rioplatense 1749–1767. Costumbres y trajes de españoles, criollos e indios. Introduction by Cutolo, Vicente. Buenos Aires: Editorial Elche.

Gerbi, Antonello (1982): La disputa del Nuevo Mundo. Historia de una polémica 1750–1990. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Guérin, Miguel Alberto (1992): “El relato de viaje americano y la redefinición sociocultural de la ecumene europea”. In: Dispositio 17, No. 42/43, pp. 1–19.

Hachim, Luis (2008): “La colonia y la colonialidad en la “Carta Dirigida a los españoles americanos” del abate Viscardo”. In: Revista de Crítica Literaria Latinoamericana 34, No. 67, pp. 47–65.

Harris, Steven (1999): “Mapping Jesuit Science: The Role of Travel in the Geography of Knowledge”. In: O’Malley, John W. et al. (Eds.): The Jesuits: Cultures, Sciences, and the Arts, 1540–1773. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 212–240.

Hudde, Hinrich (1983): “Griechisches Ideal und südamerikanische Wirklichkeit: zu José Manuel Peramás’ Vergleich zwischen Platons Staatsschriften und dem ‘Jesuitenstaat’ in Paraguay”. In: Lateinamerika-Studien 13, No. 1, pp. 355–367.

Kalista, Zdeněk (1968): “Los misioneros de los países checos que en los siglos XVII y XVIII actuaban en América Latina”. In: Ibero-Americana Pragensia, No. 2, pp. 117–161.

Kohut, Karl (2007): “Introducción. Desde los confines de los imperios ibéricos”. In: Kohut, Karl / Torales Pacheco, María Cristina (Eds.): Desde los confines de los imperios ibéricos. Los jesuitas de habla alemana en las misiones americanas. Madrid, Frankfurt: Iberoamericana / Vervuert, pp. xv-xxxvii.

Koschorke, Klaus (Ed.) (2012): Etappen der Globalisierung in christentumsgeschichtlicher Perspektive. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

Lázaro Ávila, Carlos (1996): “El reformismo borbónico y los indígenas fronterizos americanos”. In: Guimerá, Agustín (Ed.): El reformismo borbónico. Una visión interdisciplinar. Madrid: Alianza, pp. 277–292.

Lucena Giraldo, Manuel (1996): “El reformismo de frontera”. In: Guimerá, Agustín (Ed.): El reformismo borbónico. Madrid: Alianza, pp. 265–276.

Lüsebrink, Hans-Jürgen (2007): “Comprehensión y malentendidos interculturales en las obras de Baegert (Noticias de la península americana California) y Dobrizhoffer (Historia de los abipones)”. In: Kohut, Karl / Torales Pacheco, María Cristina (Eds.): Desde los confines de los imperios ibéricos. Los jesuitas de habla alemana en las misiones americanas. Madrid, Frankfurt: Iberoamericana / Vervuert, pp. 377–394.

Lüsebrink, Hans-Jürgen (2014): “Between Ethnology and Romantic Discourse: Martin Dobrizhoffer’s History of the Abipones in a (Post)modern Perspective”. In: Bernier, Marc André / Donato, Clorinda / Lüsebrink, Hans-Jürgen (Eds.): Jesuit Accounts of the Colonial Americas: Intercultural Transfers, Intellectual Disputes, and Textualities. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 127–143.

Meier, Johannes (2007a): “Las contribuciones de jesuitas centroeuropeos al conocimiento de las culturas indígenas y al desarrollo de las misiones”. In: Marzal, Manuel / Bacigalupo, Luis (Eds.): Los jesuitas y la modernidad en Iberoamérica 1549–1773. 2 Vols. Lima: Fondo Editorial de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, pp. 159–167.

Meier, Johannes (2007b): “Totus mundus nostra fit habitation”: Jesuiten aus dem deutschen Sprachraum in Portugiesisch- und Spanisch-Amerika. Stuttgart: Steiner.

Mörner, Magnus (1966): “The Expulsion of the Jesuits from Spain and Spanish America in 1767 in Light of Eighteenth-Century Regalism.” In: The Americas XXIII, No. 2,

pp. 156–164.

Mörner, Magnus (1968): Actividades políticas y económicas de los jesuitas en el Río de la Plata. La era de los Habsburgos. Buenos Aires: Paidós

Nebel, Richard (2007): “Deutschsprachige Jesuiten im kolonialen Mexiko (17./18. Jahrhundert)”. In: Kühlmann, Torsten / Müller-Jacquier, Bernd (Eds.): Deutsche in der Fremde: Assimilation, Abgrenzung, Integration. Bayreuth: Röhring, pp. 131–162.

Osterhammel, Jürgen et al. (Eds.) (2003): Geschichte der Globalisierung. Dimensionen, Prozesse, Epochen. Munich: Beck.

Osterhammel, Jürgen (2017): Die Flughöhe der Adler: historische Essays zur globalen Gegenwart. Munich: Beck.

Pinedo, Javier (2010): “El exilio de los jesuitas latinoamericanos: un creativo dolor”. In: Sanhueza, Carlos / Pinedo, Javier (Eds.): La patria interrumpida: latinoamericanos en el exilio; siglos XVIII-XX. Santiago: LOM, pp. 35–58.

Raposo, Berta (2011): “Las Tablas etnográficas (Völkertafeln) del siglo XVIII y su génesis”. In: Raposo, Berta / Gutiérrez, Isabel (Eds.): Estereotipos interculturales germano-españoles. Valencia: Publicacions Universitat de Valencia, pp. 25–34.

Rodríguez de Ceballos, Alfonso (1990): “El urbanismo de las misiones jesuíticas de América meridional: génesis, tipología y significado”. In: Relaciones artísticas entre España y América. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas; Centro de Est. Históricos; Dep. de Historia del Arte “Diego Velázquez”, pp. 151–171.

Schatz, Klaus (2000): “Die südamerikanischen Jesuiten-Reduktionen im Spiegel der Berichte deutscher Missionare”. In: Meier, Johannes (Ed.): “… usque ad ultimum terrae”: die Jesuiten und die transkontinentale Ausbreitung des Christentums 1540–1773. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 167–182.

Stanzel, Frank (1999): “Transkription der Völkertafel”. In: Stanzel, Frank (Ed.): Europäischer Völkerspiegel. Imagologisch-ethnographische Studien zu den Völkertafeln des frühen 18. Jahrhunderts. Heidelberg: Winter, p. 41.

van der Heyden, Ulrich et al. (Eds.) (2012): Missionsgeschichte als Geschichte der Globalisierung von Wissen. Transkulturelle Wissensaneignung und -vermittlung durch christliche Missionare in Afrika und Asien im 17., 18. und 19. Jahrhundert. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag.

Zanetti, Susana (2013): “Las ‘Memorias’ de Florian Paucke: una crónica singular de las misiones jesuitas del Gran Chaco.” In: América sin nombre, No. 18, pp. 178–189.