Complex Citizenship and Globalization

Alejandro Roberto Alba Meraz, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM)

Abstract: This chapter reflects upon the importance the notion of citizenship has acquired in the context of globalization. I will defend the idea that the citizen and his or her actions correspond to the political domain; specifically, in a way that confronts the problem of social order. To accomplish my objective, I have divided the chapter into three parts: a) I will define the idea of the citizen inherited from the Enlightenment; b) I will present an idea of complex citizenship and suggest why we should consider it as an alternative; and c) I will offer an interpretation designed to understand political actions from the perspective of complex citizenship.

Introduction

This chapter reflects upon the importance the notion of citizenship has acquired in the context of globalization. I will defend the idea that the citizen and his or her actions correspond to the political domain; specifically, in a way that confronts the problem of social order. This previous statement may seem unnecessary to repeat; however, I will show that it is worthy of close attention. It is a common idea to consider politics, as enacted by government officials, as a remedy to those conflicts that need a negotiated solution. Within the social aspect, many conflicts require negotiated solutions, but not all of them are political, e. g., the conflicts between parents and their descendants, or many bureaucrats’ actions concerning issues of their private lives.

Instead, politics consists of actions directed towards bringing closer those who differ in their visions of the world or perspectives that coexist in the aspect defined as public. As Bernard Crick mentions, “politics may be defined as the activity through which divergent interests reconcile within a determined government unit” (2001, p. 22). That said, the origins of politics in societies organized under the Nation States model has restricted them to the domain of the state. In this way, a citizen’s actions, whenever they are political, are related to state matters (Clarke 1996).

Certainly, political actions aim to bring together diverging positions with the purpose of generating order. Until the 1980s, the State was in charge of this task. Nevertheless, at the present time order is produced in different bodies other than the State. There are various levels of authority under which citizens feel obliged, such as local, regional, national, or supranational authorities. Additionally, there are non-state entities that contribute to generating order, such as non-governmental organisations like the UN, or civil society organizations. As a result, we can say that politics no longer determine the State’s figure per se.

Consequently, political actions have been understood in two different ways: firstly, as goal-oriented intentional actions, with specific objectives (In the case of state politics, it would be any action that questions the State.); and secondly, as actions that produce a meaning. Examples of the latter appear in concession manifestations through non-institutional means, made by the society aiming to make visible a topic that does not exist for the State. The two need not be incompatible—we can instead understand them as complementary:

This means that an action cannot be completely understood if the matrix of such is not known. But also, that an action cannot be graded as belonging to a certain category if the intention and meaning associated with it are not acknowledged. In other words, an event cannot be defined as political, social, musical, sportive or any other kind if the social matrix, as well as intentional, into which it fits is not known. (Clarke 1999, p. 99)

The notion of citizenship acts in conjunction with seeking goals and generating significance according to the social order. However, classical interpretations, such as the Illustrated, restricted their horizons for the sake of consolidating the goal-oriented perspective. In contrast, the response to this vision was the meaning-oriented perspective, as evidenced by communitarianism. This chapter will talk about another possibility, which I think is more complete—that of complex citizenship.

Recent literature has again referred to the topic of citizenship because of the recurring crisis of the state-political model—considered from the end of Welfare until the rise of the Workfare. However, there is no consensus, neither between academics nor political analysts, of which may be the main attributes of the concept of citizenship. On one side, the dominant postures understand citizenship as a legal status given as a privilege by the State, to which citizens owe loyalty for the fact that it warrantees certain prerogatives within a delimited space made by concrete physical frontiers (Carrasco 2009). Politics in this case are preceded by a relationship with the State (Rawls 2001). On the other side, there are those who consider the idea of legal citizenship as obsolete. They appeal to substantial aspects of identity—culture, language, blood, etc.—with the purpose of giving more importance to the citizen’s identity roots. In this case, politics would be based on its relationship with the roots of the community (McIntyre 2007).

Regardless of whether one is in favor of the legal formal posture, or the substantial vision, both sides restrict understanding of citizens’ actions. There are two difficulties of the previous approaches that stand out as limitations. The first is related to the right of assistance given on behalf of the States to illegal migrants groups. The second is the type of social benefit program focused on guest workers in nations such as Germany or Canada, which originated from the need to hire workers from other countries temporarily to satisfy labor demand. Given the impossibility of making migrants or guest workers return to their native countries, there are two suggested main solutions—integration into the State through naturalization processes or Workfare.

Integrated people lose substantial aspects of their original culture, conferring it to the private domain. This represents one of the main complaints from minority defender groups, because they consider that forcing the new members to break away from their language or regional habits (such as dressing or public religious practice) to adopt the hegemonic culture of the host country violates a fundamental aspect of identity that nourishes the citizen.

The second solution comes from new work demands, incarnated by the so-called Workfare. This perspective, with neocommunitarist origins, appeals to a bottom-up process. In this process, citizenship is determined by the culture, particularly the one represented by the spirit of ‘civil society’:

Such approaches convey a new hegemonic conception of governance, an instrument for forging ‘social cohesion’, a distinct ideological and political alternative to the corporative compacts between the social partners (unions and employers) which were still dominant in the Western European countries in the 1980s. (Schierup, Hansen, & Castles 2006, p. 58).

The problem with the way of understanding citizenship has to do, then, with knowing which actions count as political. The protests made by legal or illegal foreigners are not considered political. Our reflection up to this point tries to show the difficulties that entail the conceptions of state citizenship—but also, to expose the problems generated in globalized societies.

Now, to accomplish our objective I have divided the chapter into three parts: a) I will define the inherited idea of the citizen from the Enlightenment; b) I will present an idea of complex citizenship and why we should consider it as an alternative; and c) I will offer an interpretation to understand political actions through the complex citizenship’s perspective.

Citizenship and its enlightenment heritage

The idea of citizenship is, according to Pierre Rosanvallon (1999), one of the greatest achievements of Enlightenment modernity, something unparalleled that did not exist at any other previous time. Rosanvallon’s concept of citizenship is more focused on the importance of human action in politics than on other kind of extra-human or divine forces. This fact allowed people to transfer human action to an autonomous domain never before reached. Certainly, in the political thought of classical Greece and Rome, there were citizenship ideals, but they were circumscribed to the polis, beyond the borders of which people did not have any legal rights. Besides, prerogatives were limited to a reduced group—free men.

Dante (2006) and Machiavelli (1985) exemplify two different ways to understand citizenship and political action. Both showed the need to extend the political conception, by separating the agendas of power and secularizing it. They also stated the possibility of projecting a dual Roman citizenship, which could be passive (a person with rights) or active (a person who could exercise rights). Dante discerned citizenship as the joy of exercising the political action, whereas Machiavelli discerned it only as the response of the subject towards the governor.

When Enlightenment arrived, Hobbes’ citizenship idea—stating that the mere ownership of rights did not translate into an effective exercise—had matured. Therefore, only those who fulfilled residency and administrative requirements, and who exercised autonomy, could become citizens. Women, for example, could not do it (Roldan 2008; Westheimer 2008). Consequently, the scaffolding of State was required (Skinner 1999).

The requirements to determine what it takes to make politics, how a political community is formed, and how can one participate in it were elaborated during the Enlightenment. During this period, politics became independent from social domains, producing contradictory consequences. On the one hand, political actions were redefined as different from moral or economical because they are related to the State. On the other hand, there is the aspect of the fragmentation of subjectivity because when clarifying who are citizens, a part of humanity is discriminated against. This concept of citizenship is of “[…] a bounded population, with a specific set of rights and duties, excluding ‘others’ on the grounds of nationality” (Soysal 1994: p. 2).

Once established that the State is the only reference to politics, it was defined at the same time what was important and what counted in the public domain (Clarke 1996). In this way, during the Enlightenment a subjectivation mode emerged, which fractured the man, privileging a universal way of being (Pérez-Luño 1989, p. 27). The transformation-subject, or the individual’s conversion into an intelligible subject before a political regime, generated the suppression of the action’s enjoyment, as Dante would think. The citizen’s condition as a holder of political participation rights led to exclude important social groups by definition: women, children, indigenous people and foreigners.

Citizenship as an abstract unit, ideal for a procedural republic (as defined by Michael Sandel), reduced a part of the contingency of the conflicts produced by cultural identity features. But, legal identity increased the complexity in many other ways (Follesdal 2014).

I will now focus on the cognitive capacity of the Enlightenment ideal (Pettit 1990). This is the citizen’s capacity to generate actions according to specific aims. The fact that we may choose and know the consequences of that choice, as well as the corresponding responsibility when acting, is a consideration of principle. This particular attribute of subjectivity emphasizes the following four points:

- the citizen has a pattern to recognize the actions orientated to decision-making (so that the deliberative function becomes a virtue and damage prevention measure simultaneously);

- the citizen’s cognitive capacity can generate a codification register that optimizes the information that reaches the electoral subsystem;

- such a capacity results in accordance with a temporality and speciality of the political process (Palti 2007); and

- rationality from the political information channels allow the elimination of excessive information that may destabilize the system.

The cognitive capacity of the citizen expresses the impartiality principle necessary to making a political election (Allard-Tremblay 2012). Thus, any decision made shall be fair, as it will go through a depuration system of conversion from private interest into public opinion. Consequently, the citizen becomes a reflective agent, capable of ‘mediating interests and making decisions’ (Melucci 2002, p. 168). Judgment capacity, derived from the cognitive component, is appreciated because it produces choices, deliberation and decision while it reactivates options to link to the system—despite its lack of spontaneity (Pettit 1990). The epistemic capacity consists of:

[…] favoring the open circulation of relevant information, allowing intersubjective interests to participate, even with censorship bias. As it is known, they open the alternative option field that could not be considered under the system’s formal restrictions and mainly, allows the alternatives that may have negative consequences to be exposed and summited to test. (Alba-Meraz 2016)

The citizen’s cognitive capacity is a type of cognition placed to elucidate practical objectives; it is a virtue (Pettit 1990). Now I will move on to the perspective of complex citizenship.

Complex citizenship

In the Enlightenment conception, the definition of citizenship was more or less clear. It was restricted to the legal-political, so its debates were related to privilege concession—the acquisition of freedoms. However, this view omits the complaints of those who submit that there are other actions, which do not pass through the State and still, have a political value (Cfr. Franco de Sá 2017, pp. 28–29). As such, political concepts face challenges in the globalization context. Globalization is understood as “the processes of widening and deepening relations and institutions across space. Increasingly, our actions and practices systematically and mutually affect others across territorial borders.” (Sterri 2014, p.71). Regarding the relationship between citizenship and global (mainly economic) forces, it expresses a dispute between real forces for the hegemony of meaning (Zolo 2007) between the variables: a) a market’s competitive and selective logic; b) corporate logic generated by the political-state structure; and c) the logic of identity cultural processes. In view of this tension, the dynamics of the meaning of the political concepts seem to be facing a fragmentation.

In summary, the ground-breaking condition of globalized complex societies raises contradictions between citizenship conceptions generated from the legal, economic and political orders. A pertinent definition of citizenship needs to confront the tensions between the competitive logic of the global market, the configuration of an identity sense and loyalty towards politics, and the need to construct a plural us. In the words of Zolo (2007), the citizenship concept has, within the individual and the collective, the axis of complexity.

With the new globalized scenarios, politics only develops instrumental solutions that answer to the market’s logic. For example, negotiated solutions based on the private with universalization pretensions contrast with what is the proper feature of politics—the creation of a human order or an approach of them towards common interest (Arendt 2005). The current vision of politics is unable to generate future possibilities within the contingency context to which societies are exposed because of globalization (Inneraty 2012; Franco de Sá 2007). As such, it lacks the possibility of establishing a thrust of social coordination (Huysman 2006: p.10; cfr. Bell & Shaw, 1994). Consequently, the question is whether it is possible to motivate citizens with political commitment.

When politics was considered the central articulator of social life, the citizen’s integration commitments were linked to one single authority. Now that the borders are thin and politics is decentralized, loyalties are weak. This state of affairs has produced the appearance of a phenomenon called ‘flexible citizenships’ (Ong 1999). In the Asian continent, the Chinese are a noticeable example of this phenomenon. As it has been documented, a significant number of (middle and upper class) Chinese people have more than one nationality and possess multiple passports accordingly. Such documents become the instruments of their flexibility. With them, Chinese people can change their residence, nation, and commitments according to the country’s circumstances. The reasons for seeking new nationalities are mainly economic and political, but there can be others (referred to in Ong 1999). Interestingly, even in cases when Chinese people seek new nationalities, they maintain a sense of cultural belonging that transfers to their businesses or communities outside of China, making the ‘Chinese’ concept a truly transnational currency—a local-global product. Another case of flexibility is that of ‘guest workers’ who, through extraterritorial working programmes, incorporate themselves into public life in other nations. These workers are not formal citizens, but generate public structures that recognize them through social, economic, and legal benefits.

From this cultural deepening of human rights, guest nations have limited capacities to make those workers return to their countries of origin or to suspend their benefits (Soysal 1994, pp. 6–7). Flexibility, then, has become another way of producing subjectivity. It is the result of “the cultural logics of capitalist accumulation, travel and displacement that induce the subject to respond fluidly and opportunistically to change political-economic conditions.” (Ong 1999, p. 6) Thus, subjectivation processes (mechanisms expressed through a globalizing logic that provide intelligibility to the individual) introduce the capital mobility pattern to practices that give meaning to things; particularly, the ones related to loyalty, political commitment and obligation towards the authority (Savransky 2011).

The flexible citizen facing structural conditions is supposed to have a clear understanding of his or her interests. This allows establishing strategically planned objectives and having support for the advantages offered by the context, thus conditioning the citizen to express obligations and loyalty to whoever ensures his or her particular interests. However, this presents a contradiction, because it assumes that the aims and advantages that give sense to this identity are stable and do not require others’ mediation (Wisnewsky 2008).

Asian experience is an example of how interaction ranges (between local and transnational matters) give unfair privileges, because a guest worker and a transnational investor do not have the same advantages. This makes public authority sources precarious (Massey 2008, 52). Regarding this, Ong says that the citizen’s “very flexibility in geographical and social positioning is itself an effect of novel articulations between the regimes of the family, the state, and capital, the kinds of practical-technical adjustments that have implications for our understanding of the late modern subject.” (1999, p. 3)

Defenders of globalization respond to critics posing a fallacy. They admit as a premise that the market does not have as an objective the destruction of politics. The market has as purpose to make available to people a wide variety of options, and those options are subjected to people’s choice. Then, not admitting the diversification of the authority sources becomes a bottleneck that uniforms motivation and therefore impoverishes the decision’s scheme. In this way, only the market could favor the plurality that enriches politics. The citizen “[…] embodies the split between state-imposed identity and personal identity caused by political upheavals, migration, and changing global markets.” (Ong 1999, p. 2)

The promoters of flexibility omit the historical and material conditions of structural context. They assume that they can manipulate citizenship according to their interests and omit that such abstraction produces simultaneously a variety of forms of exclusion, hidden in the constitution processes of identity (Savransky 2011). Globalization theorists point out that flexibility improves the notion of citizenship by endowing it with particular features. However, flexibility also produces fragmentation—it makes identity precarious. While flexibility certainly multiplies differences, it does not find a way to generate an axis that articulates those differences for the sake of public affairs. Putting it simply, flexible citizenship makes the citizens of poor countries pay for rich citizens’ advantages facing a ‘differentiated world economy’ (Zolo 2007, p. 49).

In response to the flexible postures, I suggest the perspective of complexity. I subscribe to Zolo’s definition of complexity as:

[…] the cognitive situation in which agents, whether they are individual or social groups, find themselves. The relations which agents construct and project on their environment in their attempts at self-orientation—i. e. at arrangement, prediction, planning, manipulation—will be more or less complex according to circumstance. (Zolo 1992, p. 2)

Citizenship as a complex phenomenon admits the presence of a deep global logic in identity processes—besides the meanings generated by transnational and imaginative political practices. Under this approach, politics are not derived from subordination to the State. It is an affair of strategic ‘practices’ that consist of:

[…] the exercise and mobilization of social demands through a certain performance. Then, these can act intramarco and in consequence, reproduce parameters by which the recognition, distribution and, of course, cultural identity are defined. But it can also be extramarco. Hence, to (per)form in confrontation with recognition’s own terms, giving rise to even more radical social and identity transformations and, opening space for intercultural identification and the debate about citizenship terms. (Savransky, 2011: p.120)

The functionality of complexity is to show the areas of uncertainty generated by the accumulation of information (security, property, prestige, money, power, time, information, etc.) that nourishes identity, without leaving aside the ‘prescriptive structure of possibilities preselection’ (Zolo 1992, p. 39). This mechanism of selective regulation of social conflicts and value distribution makes it possible to “operate on the basis of stable behaviour expectations, according to collective rules” (Zolo 1992, p. 40). The aforementioned focuses on the objective of political actions—the expectations of the creation of paths to make men closer in conflict contexts—rather than on administrative criteria of immediate security. I will now offer an analysis from the perspective of complex citizenship.

The Enlightenment notion of citizenship, seen as a legal status, is insufficient to address the three variables mentioned in the previous section: market, state and pertinence. This being the case, neither individuals nor collectives can act in isolation, without the support of structures and variables. In this sense, as I have claimed, citizen identity can be explained as the result of agent’s practices, and within them, the subjects and structures that are integrated into a relational, reflexive and strategic context. It does not seem excessive to emphasize that the constitution of the citizen’s identity is not governed only by the broadening of the conventional political frame. It must include the acquisition of new freedoms, because, refining the political subsystem does not transform by itself the nature of our debate. This is why Nancy Fraser has started to reinterpret politics from a three-dimensional perspective.

Under our perspective of complexity, the subjectivation process occurs through the practices in which the subject is. This implies that relevance should be given to the ‘“subjective” adhesion to an order’ (Savransky 2011, p. 118). Individualization—the attribution of a sense to the subject through social action—is double-edged: if people exist within an organized world, then all aims come from interaction. There is clearly a presence of social control in this interaction, which increases according to the different levels of ‘socializing’ pressure. This social control is then transferred to the motivational and cognitive structures of individuals (Melucci 2002, p. 171). It is important to consider the asymmetries that subjects and collectives face when interacting with different authority systems.

Let us return to the essential component of politics. Such activity has to do with the conciliation forms of divergent interests within a government unity orientated towards the common good. I will now describe the ways in which this goal is pretended to be reached.

The case I propose is far from antagonistic postures that we shall name ‘top-bottom’ or of the ‘bottom-top’ through which citizenship is presented, or rather as the result of a decision orientated from the elites for the sake of a predetermined general conception beyond social practices. When citizenship is conceived as a process directed by social movements—from bottom to top—it encourages changes directed by homogenizing social forces:

Here citizenship is the result of the ideal construction of an order produced from the decisions of elites. Social performers are interrelated with power in a permanent way, within a wider social system that demands interaction as a unit beyond their internal divisions and generates an orientation towards the inferior layers. Here the authority is in charge by decree. We can find an example in the conversion process from subjects to citizens, as in the Spanish colonies, during the enactment of the Constitution of Cadiz in 1812.

This scheme could be adjusted to the imagination of social revolutions, where an apparently stable organization system is transformed by the complainants’ demands, in order to secure advantages in a context run by weak rules, maintained by a general state of injustice. Examples in Latin America are within the Mexican constitutions of Apatzingán in 1814 or the Constitution of 1857.

(in which the conditions are formed by violent or defensive, damage or protection reasons)

In this scheme, citizenship is in permanent reprocessing and unable to be established, due to its lack of unity regarding its objectives. In this scheme, the political value of citizenship is usually mistaken for consumable goods of other dimensions— economic, legal or cultural. Former Yugoslavia can be considered a particular case within this scheme, in which the fragmentation of identities cannot generate an orientation to form a unity due to the competence of powers.

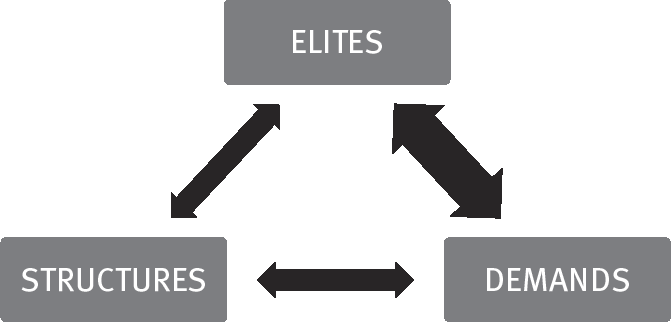

Complex Relational Citizenship Scheme

In this scheme, the concept of subject lacks a strong denomination for identity constitution. The conflicts are produced by a formal framing of institutions, one of which is the political structure. Within this political structure, displacements can be made because there are different relevant aspects to consider—personal, local, regional or global interests. Additionally, a citizen’s circumstances are temporally and spatially defined, and his or her knowledge of context and possibilities are conceivable, but not completely unknown. The demands of a particular citizen match the objectives of other individuals. In this scheme, the parties are involved in the constitution of different identities that have differentiated performances. The concept of citizenship is the result of the interaction between the chain of social demands, the social structure and the elites’ perspective. This interaction develops a structure, which promotes a demand that can be more or less integrating. In this moment, the demands could be the supplies for social structures. These resources are integrated to an imaginary, but the structure is invaded by the limits of elites. Here there are two moments:

- In the first moment, the structure of demands is constituted. This structure links events that are usually antagonistic—for instance, ‘who faces whom’ or ‘who is who’—establishing with it an identifiable polemic, in which the formation of identities is necessary (Laclau & Mouffe 1985).

- Once these links are established, the identity is then transferred to the contexts that created it. This kind of identity can be further broken down into two moments: a) a definition of citizenship is constituted that usually seems to be unitary (for example, it can be called liberal citizenship, equalitarian citizenship, etc.); and b) the definition then loses its content—freedom, equality or inclusion—and becomes a floating concept.

I appeal to the idea of Laclau. The different contexts change the use of concepts making them more restrictive. For example, during the nineteenth century in Mexico, the notion of a liberal citizen (driven by the Cadiz Cortes after Ferdinand VII’s abdication) was interpreted in a negative way by the Mexican indigenous people. They considered such status harmful for the autochthonous communities and thought that the implications only benefitted those who adjusted to an individualistic ideal. The more European you were, the closer you were to citizenship. This triggered the quest for shelter in domestic networks, in order to be supported by a collectivist citizenship, even though they did not fulfil the requirements to be called a citizen.

What can we extract from this scheme? It can be inferred that concrete historical events dispute for the configuration of an identity, not necessarily linked to a specific context or claim. The identity of a demand can come together from another event or series of events, which allows the founding of a concept.

This scheme is an analytical exercise that shows how certain practices aim to reclaim the identity of citizenship, facing exclusion. It can be modelled from different demand platforms. The requests for inclusion can be highly diverse. Some concepts expressed from the interior of the demands chain can be employment, political recognition, migration conflicts, economical inclusion, etc. One of these demands may be presented like the flag of a social identity that gets to reunify different interests or to make them coexist. This positioning puts a ‘mark’ upon diversity—it ‘enriches the chain’s content’, because it generates a dialectic effect in which apparently the chain is fulfilled; obtaining more thickness, it acquires a politically relevant sense.

In this way, the social conflict expressed in the struggles for citizenship acquires a fundamentally political aspect, in which it is determined how power is distributed according to the possible coalitions that can be formed by agents that pursue their demands. The idea of political power is a relational notion. Everything refers to the obtaining of resources in a wide sense to reduce risks. However, power is not absolute, but relative. The use of power requires the possibility to evaluate whether it is more appropriate to perform cost-benefit calculations, or to construct symbolic resources in order to form the identity.

I find this scheme to be the most adequate way to understand the effect of power constituting a coalition. The idea is that the elites’ threats do not determine the chain of demands. However, they introduce an element in this chain, which is the spectre of ‘the who’. That is, both demands and limits imposed by elites become supplies for social structures. In this perspective, those elements conform the social imaginary whose elements orientate the concept of citizenship.

My scheme shows that the structure of demands emerges from complex practices that constitute and organize social relationships. Within these demands, the concepts are regulated by a principle that does not remain just in aggregation. In this sense, citizenship is an ‘overdetermined’ identity—i.e., it contains a process that cannot become universal, because in a certain sense, it is formed by fragments. For the same reason, identity cannot become essence.

Finally, following this consideration, it can be accepted that there is nothing pre-determined in the social aspect: there is no meaning; ‘the’ citizen does not exist. There are citizenships—or, following Savransky, there are ‘forms of subjectivity and political investiture’ (2011, p. 120) susceptible to revision and critical reformulation.

Bibliography

Alba-Meraz, Alejandro Roberto (2016): “Repensando la participación política. Una perspectiva desde de la contingencia y la deliberación”. In: Revista Internacional de éticas aplicadas DILEMATA, 8. No. 22, pp. 39–53.

Aligheri, Dante (2006): De la Monarquía. Buenos Aires: Losada.

Allard-Tremblay, Yann (2012): “The Epistemic Edge of Mayority Votting over Lottery Voting”. In: Res Publica, 18, pp. 207–223.

Arendt, Hannah (2005): The Promise of Politics. New York: Schoken Books.

Bell, David Scott / Shaw, Eric (Eds.) (1994): Conflict and Cohesion in Western European Social Democratic Parties. London, New York: Pinter Publishers.

Carrasco, Nemrod (2009): “Ciudadanía global versus Estado-nación: la inversión de Hegel”. In: Arstolabio. Revista Internacional de Filosofía, No. 8, pp. 35–42.

Clarke, Paul Barry (1996): Deep Citizenship. London, Chicago: Pluto Press.

Crick, Bernard (2001): En defensa de la política. Barcelona: Tusquets Editores

Follesdal, Andreas (2014): “Global citizenship”. In: A. Sterri (Ed.) Global Citizenship— Challenges and Responsibility in an Interconnected World. Rotterdam, Boston, Taipei: Sense Publishers, pp. 71–82.

Huysman, Jef (2006): The Politics of Insecurity. Fear, Migration and Asylum in the EU. London, New York: Routledge.

Laclau, Ernesto / Mouffe, Chantal (1985): Hegemony and Socialist Strategy. Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. London, New York: Verso.

Luhmann, Niklas (1998): Complejidad y modernidad. De la unidad a la diferencia. Madrid: Editorial Trotta.

Massey, Doreen (2005): For Space. London, California: SAGE Publications.

Massey, Doreen (2008): Ciudad Mundial, Caracas: Fundación Editorial El perro y la rana / Ministerio de la Cultura del Gobierno de Venezuela.

Machiavelli, Niccolò (1985): The Prince. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

McIntyre, Alasdair (2007): After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory (3rd ed.). Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press.

Mellucci, Alberto (2002): Acción colectiva, vida cotidiana y democracia. México: El Colegio de México.

Ong, Aihwa (1999): Flexible Citizenship. The cultural logics of Transnationality. Durham, London: Duke University Press.

Palti, Elias (2007): El tiempo de la política. El siglo XIX reconsiderado. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI editores.

Pérez-Luño, Antonio Enrique (1989): Ciudadanía y definiciones. Valencia: Universidad de Valencia, Espagrafic

Pettit, Philip (1990): “Virtus normativa: Rational Choice Perspectives”. In: Ethics 100, (4), No. 6, pp. 725–755.

Rawls, John (2001): Justice as Fairness: A Restatement. Cambridge, London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Roldán, Concha (2008): “Mujer y razón práctica en la Ilustración alemana”. In: A. Puleo, (coord.): El reto de la igualdad de género. Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva

Rosanvallon, Pierre (1999): La consagración del ciudadano. Historia del sufragio universal en Francia. México: Instituto Mora.

Sá, Alexander Franco de (2007): “Despolitización y poder. Del declive de la soberanía al poder total”. In: Jara, J. (eds). La política en la era de la globalización. Providencia Chile: Editorial Cuarto Propio.

Savransky, Martin (2011): “Ciudadanía, violencia epistémica y subjetividad”. In: Revista CIDOB d′afers Internacionals, No. 95, pp. 113–123.

Schierup, Carl Urik / Hansen, Peo / Castles, Stephen (2006): Migration, Citizenship, and the European Welfare State. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Skinner, Quentin (1993): “Two concepts of citizenship”. In: Tijdschrift Voor Filosofie, Leuven, 55, No. 3, pp. 403–419.

Steenbergen, Bart von (1994): “The Condition of citizenship. An Introduction”. In: Van Steenbergen: The Condition of Citizenship. London: SAGE Publications.

Soysal, Yasemin Nuhoğlu (1994): Limits of Citizenship. Migrants and Postnational Membership in Europe. Chicago, London: The University of Chicago.

Sterri, Aksel (2014): “Introduction”. In: Sterri, A. (Ed.): Global Citizen—Challenges and Responsibility in an Interconnected World. Rotterdam, Boston, Taipei: Sense Publishers.

Westheimer, Joel (2008): “On the Relationship between Political and Moral Engagement”. In: F.K. Oser / W. Veugelers (Eds.): Getting involved: Global Citizenship Development and Sources of Moral Values. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense Publishers, pp. 17–29.

Wisnewski, Jeremy (2008): The Politics of Agency. Toward a Pragmatic Approach to the Philosophical Anthropology. Aldershot, Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Company.

Zolo, Danilo (2007): “Ciudadanía y globalización”. In: Análisis político, No. 61, Bogotá, pp. 45–53.

Zolo, Danilo (1992): Democracy and Complexity. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Zolo, Danilo (1989): Reflexive Epistemology. Dordrecht, London, Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.