I get tired of all the hype I read and hear about the pace of change. On the other hand, when Lewin’s student and my father’s mentor Ron Lippitt speaks, I listen, and he had this to say back in 1958 (the year before I was born):

“The modern world is, above everything else, a world of rapid change. This is something in which observers in every field of thought and knowledge are agreed. What does it mean? Many things of course but perhaps its primary meaning lies in its effect upon people. It means that people, too, must change, must acquire an unaccustomed facility for change, if they are to live in the modern world...It means that if we are to maintain our health and a creative relationship with the world around us, we must be actively engaged in change efforts directed toward ourselves and toward our material, social, and spiritual environments (Lippitt et al, 1958, p3).”

In his co-authored book, The Dynamics of Planned Change, Lippitt offers this simple definition:

“planned change … a deliberate effort to improve the system… (Lippitt et al, 1958, p10).”

That brings us to one of Lewin’s best known and most controversial models. Published with only minor alterations in two different articles Frontiers in Group Dynamics (Lewin 1947, 1997, p330) and Group Decision and Social Change (Lewin, 1948, 1999, p282), Lewin summarized the process of planned change this way.

Changing as Three Steps: Unfreezing, Moving, and Freezing of Group Standards

A change toward a higher level of group performance is frequently short lived; after a “shot in the arm,” group life soon returns to the previous level. This indicates that it does not suffice to define the objective of a planned change in group performance as the reaching of a different level. Permanency of the new level, or permanency for a desired period, should be included in the objective. A successful change includes therefore three aspects: unfreezing (if necessary) the present level L1, moving to the new level L2, and freezing group life on the new level. Since any level is determined by a force field, permanency implies that the new force field is made relatively secure against change.

The “unfreezing” of the present level may involve quite different problems in different cases. Allport has described the “catharsis” which seems to be necessary before prejudices can be removed. To break open the shell of complacency and self-righteousness it is sometimes necessary to bring about deliberately an emotional stir-up.

The same holds for the problem of freezing the new level. Sometimes it is possible to establish an organizational setup which is equivalent to a stable circular causal process.

Critics of Lewin have said this model of change as three steps (dubbed CATS by some) is too simple. I counter such criticism at a number of levels, the first being that the same could be said of the simplification of any phenomenon, and that simplification, in the right dose, is very helpful. Unfreezing, moving, and freezing is an intentional simplification, to create a framework for the process of planned change. Lewin was well aware that the actual effort of changing something is complicated and full of setbacks and surprises, many of which emerge along the way. He is often quoted as saying1,

“If you want to understand something, try to change it.”

_______________

1. I could not locate a source for this quote, even though I could buy a notebook on Amazon with this quote on the cover attributed to Lewin.

Lewin never assumed smooth sailing in any action research or other venture. As he was giving birth to the Commission on Community Interrelations, in a letter to his funding source, Lewin put it this way, “I know that we will have to face an unknown number of obstacles, the most severe of which, I am sure, is hidden from us at present. The sailing for a while may be easier than I expect. But somewhere along the road, maybe in a half-year, maybe in two years, I am sure we will have to face major crisis. I have observed this type of development in many research undertakings, and we will have to be unusually lucky if this time we avoid it. To my mind the difference between success and defeat in such undertakings depends mainly upon the willingness and the guts to pull through such periods. It seems to me decisive that one knows that such developments are the rule, that one is not afraid of this period, and that one holds up a team that is able to pull through (my bolding) (Morrow, 1969, p176).”

Diving into the complexity of change, Lewin writes, “To change the level of velocity of a river its bed has to be narrowed down or widened, rectified, cleared from rocks, etc. To decide how best to bring about such an actual change, it does not suffice to consider one property. The total circumstances have to be examined. For changing a social equilibrium, too, one has to consider the total social field: the groups and subgroups involved, their relations, their value systems, etc. The constellation of the social field as a whole has to be studied and so reorganized that social events flow differently (my bolding) (Lewin, 1947, 1997, p327).”

With such complexity in mind, Lewin devised methods of planned change that address enough of the “constellation of the social field as a whole” to reliably implement and sustain the desired outcomes.

He was also quite clear that freezing at the new level is not some sort of final or permanent condition. Change is continuous. “Change and constancy are relative concepts; group life is never without change, merely differences in the amount and type of change exist (my bolding) (Lewin, 1947, 1997, p308).” On the other hand, his research, validated by the experience of my father, my colleagues, and I, show that through his basic methods a new and resilient homeostasis can reliably be achieved.

In his 1943 essay, Psychological Ecology (Lewin, 1943, 1997, p290), Lewin uses his Food Habits action research as an example for explaining his theory of planned change, including the application of group dynamics and field theory.

The Field Approach: Culture and Group Life as Quasi-Stationary Processes

This question of planned change or of any “social engineering” is identical with the question: What “conditions” have to be changed to bring about a given result and how can one change these conditions with the means at hand?

One should view the present situation—the status quoas being maintained by certain conditions or forces. A culture —for instance, the food habits of a given group at a given time —is not a static affair but a live process like a river which moves but still keeps a recognizable form. In other words, we have to deal, in group life as in individual life, with what is known in physics as “quasi-stationary” processes.

Food habits do not occur in empty space. They are part and parcel of the daily rhythm of being awake and asleep; of being alone and in a group; of earning a living and playing; of being a member of a town, a family, a social class, a religious group, a nation; of living in a hot or a cool climate; in a rural area or a city, in a district with good groceries and restaurants or in an area of poor and irregular food supply. Somehow all of these factors affect food habits at any given time. They determine the food habits of a group every day anew just as the amount of water supply and the nature of the riverbed determine from day to day the flow of the river, its constancy, or its change.

Food habits of a group, as well as such phenomena as the speed of production in a factory, are the result of a multitude of forces. Some forces support each other, some oppose each other. Some are driving forces, others restraining forces. Like the velocity of a river, the actual conduct of a group depends upon the level (for instance, the speed of production) at which these conflicting forces reach a state of equilibrium (my bolding). To speak of a certain culture pattern—for instance, the food habits of a group—implies that the constellation of these forces remains the same for a period or at least that they find their state of equilibrium at a constant level during that period.

Neither group “habits” nor individual “habits” can be understood sufficiently by a theory which limits its consideration to the processes themselves and conceives of the “habit” as a kind of frozen linkage, an “association” between these processes. Instead, habits will have to be conceived of as a result of forces in the organism and its life space, in the group and its setting. The structure of the organism, of the group, of the setting, or whatever name the field might have in the given case, has to be represented and the forces in the various parts of the field have to be analyzed if the processes (which might be either constant “habits” or changes) are to be understood scientifically. The process is but the epiphenomenon, the real object of study is the constellation of forces.

Therefore, to predict which changes in conditions will have what result we have to conceive of the life of the group as the result of specific constellations of forces within a larger setting. In other words, scientific predictions or advice for methods of change should be based on an analysis of the “field as a whole,” including both its psychological and nonpsychological aspects.

Figure 5.1

A positive central field of forces (Lewin, 1946, 1997, p349)

Force field analysis then, as mentioned earlier “to be done locally,” is critical to unfreezing the current state. In field theory there are two types of forces, holding the current conditions in quasi-stasis or homeostasis.

Driving and Restraining Forces

The forces toward a positive, or away from a negative, valence can be called driving forces (see Figure 5.1, above). They lead to locomotion. These locomotions might be hindered by physical or social obstacles. Such barriers correspond to restraining forces. Restraining forces, as such, do not lead to locomotion, but they do influence the effect of driving forces (Lewin, 1946, 1997, 351).

Without the perspective of field theory, most try to bring about change by adding or increasing a driving force. This predictably leads to an increase in counter forces, and an elimination or reduction of any gains. As Lewin put it, “…a change brought about by adding forces in its direction leads to an increase in tension (Lewin, 1947, 1997, p324).” He elaborates in the following passage.

Two Basic Methods of Changing Level of Conduct

For any type of social management, it is of great practical importance that levels of quasi-stationary equilibria can be changed in either of two ways: by adding forces in the desired direction or by diminishing opposing forces. If a change… is brought about by increasing the forces toward… the secondary effects should be different from the case where the same change of level is brought about by diminishing the opposing forces.

…In the first case, the process… would be accomplished by a state of relatively high tension, in the second case, by a state of relatively low tension. Since increase of tension above a certain degree is likely to be paralleled by higher aggressiveness, higher emotionality, and lower constructiveness, it is clear that as a rule, the second method will be preferable to the high pressure method (my bolding) (Lewin, 1948, 1999, p280).

As usual, Lewin illustrated this phenomenon:

Figure 5.2

Gradients of resultant forces (Lewin, 1948, 1999, p280)

Push and people will push back. Push hard and the push back will be stronger. Reduce the restraining forces, and change will happen more smoothly and be more sustainable. Lewin’s research and my own experience validate this theory. The question becomes then, what is the alternative to pushing? As he pointed out in the paper Group Decision and Social Change (Lewin, 1948, 1999, p273), Lewin’s hypothesis was that the key to addressing and reducing restraining forces lay in group dynamics.

Individual Versus Group

The experiment does not try to bring about change of food habits by an approach to the individual, as such. Nor does it use the “mass approach” characteristic of radio and newspaper propaganda. Closer scrutiny shows that both the mass approach and the individual approach place the individual in a quasi-private, psychologically isolated situation with himself and his own ideas. Although he may physically be part of a group listening to a lecture, for example, he finds himself, psychologically speaking, in an “individual situation.”

Even lecturing to a room full of employees, or conducting a public relations campaign for a change effort, is essentially approaching each person as an individual. While such efforts can play a role in disseminating information, they are inadequate for instilling lasting change in behaviors or beliefs. Lewin explains why: “One of the reasons why ‘group carried changes’ are more readily brought about seems to be the unwillingness of the individual to depart too far from group standards—he is likely to change only if the group changes (Lewin, 1948, 1999, p273).” With this in mind, the following excerpt from Frontiers in Group Dynamics (Lewin, 1947, 1997, p330) becomes a core principle of Lewin’s approach to planned change.

Group Decision as a Change Procedure

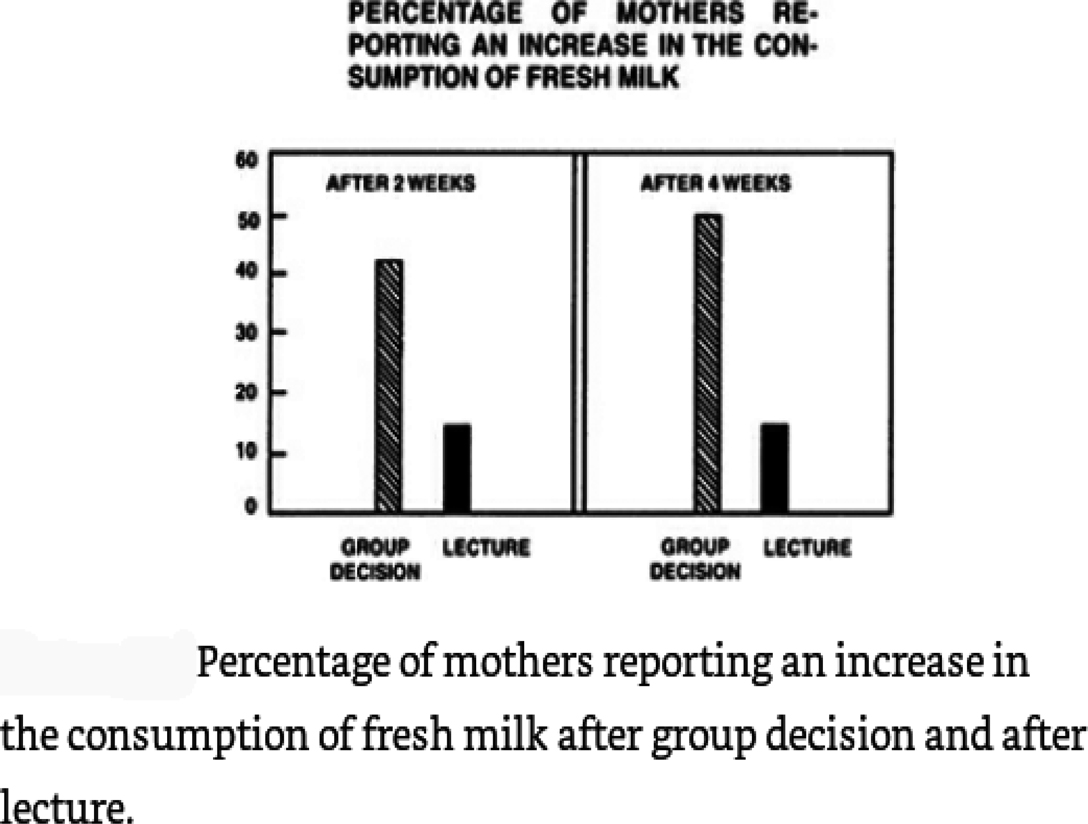

The following example of a process of group decision concerns housewives living in a midwestern town, some of whom were exposed to a good lecture about the value of greater consumption of fresh milk and some of whom were involved in a discussion leading step by step to the decision to increase milk consumption. No high-pressure salesmanship was applied in fact, pressure was carefully avoided. The amount of time used was equal in the two groups. The change in milk consumption was checked after two and four weeks. Figure 5.3 (below) indicates the superiority of group decision.

Figure 5.3

Percentage of mothers reporting an increase in the consumption of fresh milk (Lewin, 1948, 1999, p275)

Lewin replicated similar results time and again. As an aside, Lewin indeed exposed them to “a good lecture.” Margaret Mead was one of the lecturers. She recalled to Alfred Marrow with a chuckle of how she was brought into a similar food habits study as a “…prestige expert from Washington to express publicly my high approval of turnips—which had no effect at all ( Marrow, 1969, p130).” Mead notes (again in Marrow, same page) that it was during the food habits studies, for which she had originally recruited Lewin, that the concept of “group decision” was formed.

Figure 5.4

A highly approved turnip

The food habits studies showed that people, when they are lectured to through traditional classroom methods, even though they are in a group are still in a primarily individual experience and isolated in their thinking. They only change as a group under such conditions if there happens to be a high occurrence of simultaneous individual change. Such a simultaneous individual change would require extraordinary circumstances. In contrast, when Lewin’s participants in this and many other studies were encouraged to think out loud with each other in a facilitated group discussion, the group dynamics shifted from a restraining force to a driving force. The odds of individual change happening and sustaining go way up.

To be clear, this difference between group and individual methods is not magic. It doesn’t come from simply locking a group in a room and leaving the quality of their discussion to chance. As Lewin put it: “The procedure of group decision in this experiment follows a step-by-step method designed a) to secure high involvement, and b) not to impede freedom of decision (Lewin, 1948, 1999, p271).” Lewin goes on, “It is possible that the success of group decision and particularly the permanency of the effect is, in part, due to the attempt to bring about a favorable decision by removing counterforces within the individuals rather than by applying outside pressure (Lewin, 1948, 1999, p281).” The counterforces within the individual can only diminish of their own volition. That is most likely to occur if people feel free to speak their minds, and if they are able to hear the opinions of their peers, whom they likely will trust more than an “expert.” This holds true even if, like the mothers in the food habits study, they are strangers to each other at the beginning of the process.

Here we are seeing the shift away from “pushing” operationalized. As Lewin put it: “The group decision procedure which is used here attempts to avoid high pressure methods and is sensitive to resistance to change. In the experiment by Bavalas on changing production in factory work… for instance, no attempt was made to set the new production goal by majority vote because a majority vote forces some group members to produce more than they consider appropriate. These individuals are likely to have some inner resistance. Instead, a procedure was followed by which a goal was chosen on which everyone could agree fully (Lewin, 1948, 1999, p281).”

This rejection of “high pressure methods” became the foundation of the Knowledge Retrieval Implication Derivation or KRID model devised by Drs. Ron Lippitt and Charles Jung in the 1950s to assure the effective implementation of best practices. My father, brother Chris, and I have been applying KRID ever since. The step-by-step method is detailed in Appendix C.

Lewin explains the importance of group decision in planned change this way:

The experiments reported here cover but a few of the necessary variations. Although in some cases the procedure is relatively easily executed, in others it requires skill and presupposes certain general conditions. Managers rushing into a factory to raise production by group decisions are likely to encounter failure. In social management as in medicine there are no patent medicines and each case demands careful diagnosis. The experiments with group decision are nevertheless sufficiently advanced to clarify some of the general problems of social change.

We have seen that a planned social change may be thought of as composed of unfreezing, change of level, and freezing on the new level. In all three respects group decision has the general advantage of the group procedure.

If one uses individual procedures, the force field which corresponds to the dependence of the individual on a valued standard acts as a resistance to change. If, however, one succeeds in changing group standards, this same force field will tend to facilitate changing the individual and will tend to stabilize the individual conduct on the new group level (my bolding) (Lewin, 1947, 1997, p331).

Lewin’s change method includes group decision as a reliable tool in changing the configuration of forces so as to drive and sustain change. The process leading to the group decision had to be active, not passive: “…there is a great difference in asking for a decision after a lecture or after a discussion. Since discussion involves active participation by the audience and a chance to express motivation towards different alternatives, the audience might be more ready to ‘make up its mind,’ that is to make a decision after a group discussion than after a lecture. A group discussion gives the leader a better indication of where the audience stands and what particular obstacles have to be overcome (Lewin, 1948, 1999, p273).”

In group decision, Lewin’s theories regarding the social construction of reality and of intention/commitment/ aspiration are validated. The first paragraph below is based on a study in which the researchers try to convince a group of college students to switch from white bread to whole wheat:

One reason why group decision facilitates change is illustrated by Willerman… When the change was simply requested the degree of eagerness varied greatly with the degree of personal preference for whole wheat. In case of group decision the eagerness seems to be relatively independent of personal preference the individual seems to act mainly as “group member.”

A second factor favoring group decision has to do with the relation between motivation and action. A lecture and particularly a discussion may be quite effective in setting up motivations in the desired direction. Motivation alone, however, does not suffice to lead to change. That presupposes a link between motivation and action. This link is provided by the decision but it usually is not provided by lectures or even by discussions. This seems to be, at least in part, the explanation for the otherwise paradoxical fact that a process like decision which takes only a few minutes is able to affect conduct for many months to come. The decision links motivation to action and, at the same time, seems to have a “freezing” effect which is partly due to the individual’s tendency to “stick to his decision” and partly to the “commitment to a group.” The importance of the second factor would be different for a students’ cooperative where the individuals remain together, for housewives from the same block who see each other once in a while, and for farm mothers who are not in contact with each other. The experiments show, however, that even decisions concerning individual achievement can be effective which are made in a group setting of persons who do not see each other again (my bolding) (Lewin, 1947, 1997, p332).

If there is magic in Lewin’s methods, this might be it. The effect of group decision, if participants really have a chance to dialogue with their peers and with people in positions of formal leadership, if they really have a chance, within reasonable limits, to make up their own minds, is an astonishingly reliable path to successful implementation of sustainable change. I was trained by my father in a basic process of group decision when I was 24, totally wet-behind-the-ears, dealing with understandably cynical elders in difficult manufacturing conditions, and it worked. I’m a living Lewinian research project, and I wouldn’t want it any other way.

We’ll explore Lewin’s methods further, as well as my father’s adaptations. Meanwhile, let us allow Lewin to bring this chapter to a close with the following nuggets of planned change wisdom_

A theory emerges that one of the causes of resistance to change lies in the relation between the individual and the value of group standards. This theory permits conclusions concerning the resistance of certain types of social equilibria to change, the unfreezing, moving, and freezing of a level, and the effectiveness of group procedures for changing attitudes or conduct.

The analytical tools used are equally applicable to cultural, economic, sociological, and psychological aspects of group life. They fit a great variety of processes such as production levels of a factory, a work-team and an individual worker; changes of abilities of an individual and of capacities of a country; group standards with and without cultural value; activities of one group and the interaction between groups, between individuals, and between individuals and groups.

The analysis concedes equal reality to all aspects of group life and to social units of all sizes (Lewin, 1947, 1997, p334).

Universal tools. I believe it. Let’s go deeper now into Lewin’s action research on group dynamics.