Fiscal and Monetary Policies

Introduction: Expansionary and Contractionary Policies

The macroeconomic policymakers are the president, Congress, and the Federal Reserve. Macroeconomic policies are also referred to as stabilization policies. The government adopts macroeconomic policies to improve and stabilize economic performance. Stabilization policies focus on macroeconomic goals such as high real GDP growth, low unemployment, and low stable inflation. To attain these objectives, macroeconomic policies may be expansionary or contractionary.

Expansionary policies are used to alleviate a macroeconomic slowdown, in other words a recessionary gap. Keynesianism is the active use of an expansionary policy to cure a weak economy. According to Keynesianism, an expansionary policy increases aggregate demand, which increases economic growth and reduces unemployment. Keynesianism contrasts with the classical view for resolving a recessionary gap. Classicalism emphasizes the process of market forces rather than government activism.

Figure 4.1 shows the impact of a Keynesian expansionary policy in the expectational Phillips curve framework.

Figure 4.1 Expansionary macroeconomic policy

Suppose the economy is at point 1 in a recessionary gap. Unemployment is equal to 6 percent. This is greater than the natural rate of 5 percent. Inflation is about 2 percent at point 1. Now, assume the government seeks to close the recessionary gap through an expansionary macroeconomic policy. Macroeconomic demand rises. This leads to higher RGDP growth and lower unemployment. The economy moves up and to the left along the short-run Phillips curve S1 from point 1 to point 2. The recessionary gap is resolved as unemployment declines from 6 percent to the natural rate of 5 percent. An expansionary policy, however, may cause an adverse side effect of higher inflation. Demand-pull inflation develops as businesses and households increase demand for spending and are willing to pay higher prices. Inflation rises from 2 to 3 percent as the economy moves from point 1 to point 2. Given the initial recessionary gap, the effects of an expansionary policy are lower unemployment and higher inflation.

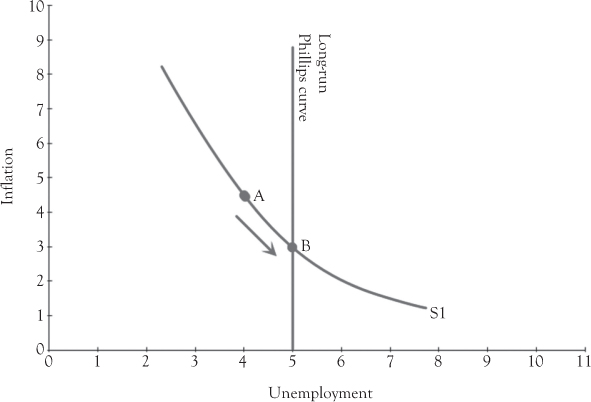

A contractionary macroeconomic policy decreases aggregate demand to alleviate an inflationary gap. The goal of contractionary policy is to reduce inflation. Figure 4.2 shows the effects of a contractionary policy in the expectational Phillips curve model.

Figure 4.2 Contractionary macroeconomic policy

Assume the economy is at point A. Unemployment is about 4 percent. This is less than the natural unemployment rate of 5 percent. The economy is in an inflationary gap and overheated. Excess macroeconomic demand occurs. Excess macroeconomic demand causes rising inflation. Inflation is about 4.5 percent at point A. Inflation is likely to rise further if excess macroeconomic demand persists.

Suppose the policymakers seek to resolve the excess macroeconomic demand or inflationary gap through a contractionary policy. Macroeconomic demand decreases. The economy moves down and to the right along the short-run Phillips curve S1 from point A to point B. The inflationary gap is closed by decreasing macroeconomic demand. Inflation falls from 4.5 to 3 percent. The contractionary policy also causes unemployment to rise from 4 percent to the natural rate of 5 percent. The contractionary policy alleviates macroeconomic overheating, and the economy moves to a long-run position of efficiency at point B. This point is efficient because it occurs on the long-run Phillips curve.

Fiscal Policy: Government Spending and Taxes

Two kinds of macroeconomic policies are available for expansionary and contractionary purposes. They are fiscal policy and monetary policy. Fiscal policy is the influence of government expenditures and taxes on macroeconomic demand and the economy as typically measured by RGDP, unemployment, inflation, and interest rates. Some of the main types of government taxes are personal and corporate income taxes, social security taxes, sales taxes, property taxes, and excise taxes. Some of the main types of government spending are national defense, government-provided health care such as Medicare and Medicaid, and public education.

The government budget equals total government spending minus total taxes. A government budget deficit occurs if government spending exceeds total taxes. A budget surplus arises if total government spending is less than total taxes. A balanced budget takes place if total government spending equals total taxes. Government debt is approximately equal to the sum of all past and present government deficits and surpluses. A government deficit causes government debt to increase, while a government surplus causes government debt to decline.

The government finances its debt obligations by borrowing from the public through issuing treasury bonds. The public consists of individuals, businesses, private banks, the central bank, and foreign buyers including foreign governments. The treasury borrows funds by printing treasury bonds that are sold to the public. From the public’s perspective, the purchase of treasury bonds is a financial investment that earns interest. From the government’s point of view, treasury bonds are the means by which the government borrows funds to finance budget deficits. A sizable portion of the national debt is purchased and held as an asset in the balance sheet of the central bank. The central bank buys treasury bonds from the public by printing new currency. This causes money supply in the economy to expand. This relates to the money supply process that is discussed later in this chapter.

Expansionary Fiscal Policy: Higher Government Spending and Lower Taxes

Fiscal policy may be expansionary or contractionary, based on whether unemployment or inflation is considered the main economic concern by policymakers. An expansionary fiscal policy focuses on attaining higher economic growth and lower unemployment. An expansionary fiscal policy consists of two tools, which are tax cuts and higher government spending.

The first tool is lower taxes. Lower income taxes among households and businesses create higher after-tax income for businesses and households. After-tax household income is called disposable income. Higher disposable income enables more consumer spending. Higher after-tax business income, such as after-tax retained corporate earnings, enables more business spending on investment in plant and equipment. Tax cuts indirectly facilitate greater consumption and investment spending among households and businesses. Lower taxes lead to higher after-tax income, greater spending, and higher aggregate demand.

The other expansionary fiscal policy tool, besides tax cuts, is higher government spending. Higher government spending directly increases macroeconomic demand. This is because government expenditure is a direct component of GDP. For example, the initial effect of higher government spending of $100 billion is an increase in GDP of $100 billion. We will discuss the subsequent effects of higher government spending later in this chapter, such as crowding-in, crowding-out, and the spending multiplier.

An expansionary fiscal policy expands macroeconomic demand. This increases RGDP and reduces unemployment. An expansionary policy, however, may cause a negative side effect of worsening inflation. The effect of an expansionary fiscal policy is shown as the movement from point 1 to point 2 in Figure 4.1. Fiscal policy also affects the government budget deficit and national debt. An expansionary fiscal policy of greater government spending or lower taxes causes a larger government budget deficit and higher national debt.

The classical macroeconomic perspective and the political right generally advocate lower taxes as the preferable expansionary fiscal policy. Lower taxes reduce the role and size of government in the economy. This permits a greater role for market forces in the economy. The classical outlook view market forces as more effective and efficient than government spending.

The Keynesian outlook and the political left often advise higher government spending as an effective expansionary fiscal policy. According to Keynesianism, higher government expenditures can offset economic slowdown in the private sector. If the private sector is weak, government spending may be increased to counterbalance low consumer spending and low business spending. Keynesianism asserts that market forces are sometimes insufficient to create a strong economy.

For an expansionary fiscal policy, Keynesianism often advocates higher government spending. This has a stronger, quicker, more reliable, and more direct impact on the economy than tax cuts. Lower taxes directly increase after-tax income. This, however, has an indirect and less certain impact on spending. Tax cuts, for example, could cause more household or business saving rather than more spending.

For instance, rather than increasing business spending, lower corporate taxes could induce corporations to buy back stocks to increase the stock price and increase shareholder wealth. If saving rises instead of spending from a tax cut, then the impact on macroeconomic demand is limited. Spending is the driving force on macroeconomic demand. The higher the spending, the higher the macroeconomic demand.

Government spending has an immediate and direct impact on macroeconomic demand and GDP. This is because government spending is a direct component of GDP. Keynesianism generally advocates higher government spending as an effective expansionary policy to create stronger economic growth. Higher government spending is a direct approach to offset weak private sector spending. Classicalism, on the other hand, generally embraces lower taxes as an effective expansionary policy to enhance economic growth. A tax cut shrinks the role of government and boosts the private sector of the economy.

Crowding-out and Crowding-in Effects

The crowding-out effect and the crowding-in effect are two important influences regarding the effectiveness of an expansionary fiscal policy. The crowding-out effect is a major factor in an efficient full-employment economy. The crowding-in effect is a major factor in an inefficient economy, such as a recession. The stronger the economy, the larger the crowding-out effect and the smaller the crowding-in effect. The weaker the economy, the smaller the crowding-out effect and the larger the crowding-in effect.

The classical view emphasizes the crowding-out effect. The crowding-out effect refers to the harmful impact that may occur from government deficit spending in a full-employment economy. The Keynesian perspective emphasizes the crowding-in effect. The crowding-in effect refers to the positive impact that may occur from government deficit spending in a weak economy.

Crowding-out is the adverse impact of government deficit spending on interest rates and business investment. Higher government spending causes the government deficit to worsen, assuming taxes are constant. A higher budget deficit may cause higher interest rates. This occurs because higher government borrowing to finance a budget deficit competes with private sector borrowing by businesses and households. The overall demand for borrowing throughout the economy increases when government debt rises. The total demand for borrowing is called the demand for loanable funds. This equals government borrowing plus private sector borrowing.

An increase in the demand for loanable funds caused by higher government debt may bid up the cost of borrowing. The interest rate is the cost of borrowing. Higher government spending and a higher budget deficit may cause higher interest rates. If interest rates rise, business borrowing to finance investment in plant and equipment becomes more expensive. Business firms consequently reduce borrowing to fund capital investment. Business investment declines and is crowded out because of higher interest rates associated with higher government debt.

If complete crowding-out occurs, then higher government spending and higher budget deficits are completely negated by an equal decline in private investment spending. Business investment declines as government spending rises. This leaves Real GDP essentially unchanged, but with higher interest rates and greater government debt. As business investment declines, future economic growth may similarly decrease.

Crowding-out, however, is likely to be partial rather than full. Government deficit spending and higher debt may cause lower private economic investment. The two effects, however, may not completely cancel out. An increase in government deficit spending by $100 billion, for example, may cause interest rates to rise and private investment to fall by $25 billion rather than $100 billion. This is partial crowding-out.

Lower government deficit spending, on the other hand, may enable greater business investment spending. A smaller government deficit reduces the demand for loanable funds. This may cause lower interest rates. If interest rates drop, business firms may increase borrowing to finance new investment in plant and equipment.

Crowding-out is likely to happen if the economy is at or near potential or full capacity. The crowding-in effect, by comparison, occurs when the economy is in a recession or experiencing low growth. Crowding-in takes place if government deficit spending triggers an even greater expansion in macroeconomic demand through the spending multiplier. According to the crowding-in effect or the spending multiplier effect, higher government expenditure triggers increases in consumer spending and higher GDP.

Suppose government spending rises by $100 billion. GDP consequently rises by $100 billion because government purchases are a direct part of GDP. This increase in government spending generates higher income of $100 billion to the sellers or suppliers of government products. For example, the suppliers could be health care providers in the Medicare program or government contractors that supply military equipment for national defense.

The suppliers of government goods spend a portion of their $100 billion in new income, perhaps $75 billion on consumer goods. This second round of spending causes GDP to rise by an additional $75 billion. This creates a further round of income, this time to sellers of consumer goods. They, in turn, increase their spending, perhaps by $60 billion. This leads to yet another round of new income and subsequent spending.

Through this multiplier process, higher government spending creates an even greater impact on macroeconomic demand and GDP. Essentially, one person’s spending becomes someone else’s income. This leads to more spending and income to others. This ripple effect of multiple rounds of income and spending occurs in response to the initial rise in government purchases. If overall macroeconomic demand eventually expands by $250 billion in reaction to an initial increase in government purchases of $100 billion, then the spending multiplier is 2.5.

Keynesianism emphasizes the crowding-in effect or spending multiplier effect of government purchases, including deficit spending, upon GDP. The classical perspective emphasizes the crowding-out effect of increased government deficit spending on higher interest rates and the possibility of reduced business investment.

Contractionary Fiscal Policy: Lower Government Spending and Higher Taxes

Government spending and taxes may be used for a contractionary macroeconomic policy. A contractionary fiscal policy may occur in two ways. They are higher taxes or lower government spending. The main goal of a contractionary fiscal policy is to reduce inflationary pressures by lowering macroeconomic demand. This, however, may cause a side effect of lower economic growth and higher unemployment. This occurs because of the short-run inflation-unemployment trade-off. A contractionary policy causes lower inflation but also less spending in the economy and fewer jobs.

A side effect of a contractionary fiscal policy is that the government budget deficit may decline. Higher taxes or lower government spending cause the budget deficit to decrease. Additionally, national debt may decline if a budget surplus occurs from higher taxes or lower government purchases.

The first type of contractionary fiscal policy is higher taxes. An increase in taxes indirectly causes lower spending. This takes place through the intermediate impact of higher taxes on after-tax household and business income. Higher taxes cause after-tax income to fall for households and businesses. Less funds are available for business investment and household consumption because of higher taxes. Lower after-tax income induces businesses and households to reduce spending. Macroeconomic demand accordingly declines. Besides higher taxes, the other contractionary fiscal policy is lower government purchases. Lower government expenditure directly decreases aggregate demand and GDP because government spending is a direct part of GDP.

Classical View and the Political Right on Contractionary Fiscal Policy

The classical perspective on contractionary fiscal policy normally prescribes lower government spending rather than higher taxes to manage inflation. Lower government expenditure reduces the role and size of the state in the economy. This is a major priority of the classical view and the political right. The political right tends to adhere to the classical macroeconomic perspective that advocates a small government sector and a large private sector.

The political right also generally advocates lower spending on government social programs rather than cuts in national defense for contractionary fiscal policy. Two considerations underlie this conservative preference on government spending. They are economic self-reliance and strong national security.

The political right stresses that the long-term solution to poverty is individual economic self-sufficiency through employment for those who are able to work. Employment is the means to self-reliance in a capitalist society. The political right maintains that government subsidies and programs that address poverty can become counterproductive. Government spending to help the poor can inadvertently perpetuate economic dependency. Government programs that deal with poverty may prolong poverty. Some recipients of government assistance may perpetually rely on government aid. The political right and the classical economic view assert that lower social spending compels some long-term recipients of government aid to seek employment.

The political left, on the other hand, maintain that cuts in antipoverty programs worsen poverty among the poor and disabled who fall between the cracks of the market system. Lower social spending causes some long-term welfare recipients to seek work. Those who do not obtain employment, however, find that their poverty worsens because of reduced social spending.

The second conservative principle on contractionary fiscal policy is the concept of strong national security. The 19th century economic philosopher Adam Smith is often considered the father of modern economics. Smith wrote on the role of the state in society and the economy. One of the main functions of government is a strong national defense according to Adam Smith and many others. Strong national security promotes a safe, secure, and stable social and economic environment for the private sector to thrive. High military spending enhances national security according to the political right. Political conservatism tends to adopt a hawkish sentiment on national security. The best way to prevent war is to prepare for war through strong national defense. The political right consequently tends to oppose military spending cuts as a contractionary fiscal policy.

Keynesian View on Contractionary Policy

Keynesianism advocates lower government spending as a contractionary fiscal policy to control inflation. The rationale is that government expenditures have a larger, more direct, quicker, and more reliable impact on macroeconomic demand than tax policy. Lower government spending causes an immediate and direct decline in macroeconomic demand.

Taxes, on the other hand, indirectly affect aggregate demand and GDP through the intermediate impact of after-tax income. Taxes directly influence after-tax business and household income. Higher taxes cause lower after-tax income. Lower after-tax business and household income may lead to lower consumption and business spending. However, some economic uncertainty occurs. Some after-tax income goes to saving instead of spending. Higher taxes may have less impact on spending and macroeconomic demand than anticipated because of saving. Households and businesses may react to higher taxes by saving less rather than spending less. If this occurs, macroeconomic demand is unchanged. In this case, consumer and business spending stay the same, while saving decreases because of higher taxes.

The Political Left and Contractionary Fiscal Policy

The political left tends to oppose contractionary fiscal policies of government spending cuts in social safety-net programs such as Medicaid, Medicare, unemployment insurance, social security, and social welfare. The political left emphasizes that lower social spending worsens economic distress among the poor.

Antipoverty government programs are often designed to provide temporary economic relief to low-income households. Social safety-net programs provide economic necessities that otherwise may be unavailable for many of the poor. Government social programs, however, have not been particularly effective in resolving the long-term root causes of poverty. Antipoverty programs can perpetuate poverty if the recipients continually rely on government assistance.

The political left typically opposes cuts in social safety-net programs as a contractionary policy. The political left often advocates lower military spending as a contractionary fiscal policy. The political left tends to embrace a military dove sentiment. Countries that overprepare for war are more likely to go to war. Excess military superiority may create an overconfidence to engage in unnecessary armed conflicts.

The political left also tends to favor a contractionary fiscal policy of higher taxes on the wealthy. The political left often supports a higher marginal income tax rate on higher-income households and businesses. This creates greater equity in disposable income across the socioeconomic spectrum. The marginal income tax rate, according to the political left, should be higher on upper-income households and businesses based on the ability-to-pay principle. Tax rates should be smaller on lower-income individuals and businesses because of lesser ability to pay.

In summary, Keynesianism and the political left generally support higher progressivity of income taxes and cuts in military spending as desirable contractionary fiscal policies to assuage inflationary pressures. The classical macroeconomic view and the political right generally favor lower government spending on social programs as a contractionary fiscal policy to dampen inflation.

The economic and political characteristics of expansionary and contractionary fiscal policies are summarized in Table 4.1.

Table 4.1 Expansionary and contractionary fiscal policies

Fiscal policy |

Goals |

Possible macroeconomic side effects |

Policy tools |

Political left |

Political right |

Expansionary fiscal policy |

Remedy recession or sluggish economic growth, reduce unemployment |

Higher inflation; larger government budget deficit |

Increase in government spending or decrease in taxes |

Increase in government spending, especially social programs |

Decrease in taxes |

Contractionary fiscal policy |

Remedy high inflation or economic overheating |

Lower economic growth, higher unemployment, possibly recession; smaller government budget deficit |

Decrease in government spending or increase in taxes |

Increase in progressivity of taxes or reduction in military spending |

Decrease in government spending on social programs |

The political right and the political left differ on the most effective approach to fiscal policy. This ideological divide is based on opposing views on the role and effectiveness of market forces versus government activism in building a strong economy with low inflation. The political left tends to support Keynesianism, while the political right tends to adhere to classicalism.

Political Influences on the Fiscal Policy Process

Fiscal policy mainly occurs through the federal budget process. This consists of the political interaction and compromise between the president and the Congress. The Congress and the president are the fiscal policymakers. The budget process also involves the macroeconomic agendas of left and right political parties. Most members of Congress and the president belong to one of the two major parties. The interaction between the Congress, the president, and the two main parties in determining fiscal policy may be cooperative or conflictual. The distribution of political party control over the executive and legislative branches affects whether the fiscal policy process is cooperative or conflictual.

If one political party controls both the legislative and executive branches, then the in-party to the White House has a strong likelihood to attain the desired fiscal policy. The fiscal policy process is relatively cooperative between the president and the Congress if a unified government occurs in which one party controls both branches. The executive and legislative branches are likely to agree on the direction and composition of fiscal policy in a unified government of one-party control.

Suppose the Republican party controls the executive and legislative branches. This happens if the president and a majority of legislators in the House and the Senate are members of the Republican party. A unified conservative government occurs. Consequently, the fiscal policy is likely to be conservative. A conservative fiscal policy emphasizes a relatively small size of government. This occurs through relatively low government spending (especially reduced social programs rather than reduced military spending) for a contractionary fiscal policy and relatively low taxes for an expansionary fiscal policy.

Fiscal policy is likely to be liberal if the Democratic party controls the legislature and the presidency. A unified liberal government occurs in this instance. A liberal fiscal policy supports a relatively larger role of government in the economy. A liberal expansionary fiscal policy consists of relatively high government expenditure, especially on social programs. A liberal contractionary fiscal policy consists of relatively high progressivity of income taxes on businesses and households.

Suppose the president is a member of one party, while most members of the House and the Senate are members of the opposing political party. A power split occurs on political party control of the two government branches. A divided government arises. For example, the president may be a Democrat while most members of the Congress are Republicans. The president is unlikely to fully attain the desired fiscal policy in a divided government. The fiscal policy is likely to be conflictual in a condition of political gridlock. The majority of members of the Congress and the president are likely to clash on the level and distribution of government spending and taxes.

Monetary Policy: Money Supply and Interest Rates

The Federal Reserve is the central bank and monetary authority in the U.S. economy. The duty of Fed is to administer monetary policy and regulate the banking system. Monetary policy is the control of money supply and interest rates to promote a strong economy with stable low inflation. Monetary policy impacts aggregate demand, with short- and long-run effects on unemployment, inflation, RGDP, and the dynamics of the business cycle. The policy is primarily administered through open market operations (OMO). It is also sometimes administered through Fed purchases of long-term private assets, such as mortgage-backed securities. This is called quantitative easing1.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is the decision-making body of the Fed that is in charge of monetary policy. The FOMC consists of 12 members. The FOMC chairperson is the chairperson of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The president appoints the Fed chairperson (of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System) to serve renewable four-year terms. The other FOMC members consist of six members of the Board of Governors, plus the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and four additional Federal Reserve district bank presidents who serve rotating one-year terms.

This somewhat complex and rotating configuration of FOMC members establishes diversity and plurality in the money supply decision-making process. This mechanism operates as a partial safeguard against excessive control over monetary policy by special interests, the president, the Congress, and the political parties.

Money Supply and Interest Rates

Money supply consists of cash held outside of banks plus bank account deposits. Most of the money supply is in the form of bank deposits, such as checking accounts, savings accounts, and bank certificates of deposit. The Fed uses several different measurements for the quantity of money in the economy, such as M1, M2, M3, and L. The M2 definition of money supply is a widely used measure. M2 consists of cash held outside of banks plus checking and savings account deposits. Money supply is measured nominally and in real terms.

The nominal money supply is the total dollar value of the amount of money in circulation. Real money supply is a measure of purchasing power. Real money supply is the value of money in relation to the prices of products throughout the economy. Real money supply equals nominal money supply divided by the aggregate price index. The aggregate price index is an indicator of the average price level of new products (see Chapter 2 for a discussion on nominal and real values). Real money supply is also called real balances.

A cause–effect relation occurs between real money supply and interest rates. Higher real money supply causes lower interest rates. Lower real money supply leads to higher interest rates. The price of money, especially from a borrower’s perspective, may be thought of as the interest rate. The interest rate and interest payments on loans reflect the price or cost of borrowing money.

According to economic market analysis, an increase in the supply of a product causes its price to decline. Alternatively, when the supply of an economic good decreases, its price goes up. Based on this concept, an inverse relation occurs between the real money supply and its price, which is the interest rate. A change in real money supply affects the interest rate. An increase in the supply of real money causes its price, the interest rate, to go down. A decrease in the real money supply causes the interest rate to go up.

Figure 4.3 shows the general inverse pattern between real balances and interest rates in the U.S. economy. The scatter graph in Figure 4.3 measures the interest rate for AAA corporate bonds along the vertical axis and the growth rate for the real M2 money supply along the horizontal axis. The economic data consists of monthly observations across the time frame from August 1992 to January 2015. The scatterplot shows a general inverse relation. This is indicated by the downward trend line. As the growth rate of real money supply goes up, the interest rate goes down. This inverse pattern signifies money demand. The money demand pattern, however, is not perfectly correlated with all the observations in the graph. Many of the data points in the scatter graph occur above and below the trend line. This occurs because other economic determinants (besides the interest rate) also affect the demand for money.

Figure 4.3 Real M2 money supply and the interest rate

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED)

Besides the interest rate, RGDP is an important factor on money demand. RGDP has a positive impact on money demand and interest rates. Higher RGDP creates a higher demand for money. A greater amount of money is needed in a growing economy to accommodate more spending. This effect is called the transactions demand for money.

Higher money demand connected with higher income and RGDP tends to cause higher interest rates. According to economic market analysis, an increase in the demand for a good will cause its price to rise. The price of money is the interest rate. A higher demand for money causes its price to rise, which is the interest rate. Alternatively, lower RGDP causes money demand to fall. In this case, less money is demanded because of less income and less spending. Interest rates therefore tend to go down.

Open Market Operations

Monetary policy mainly occurs through open market operations (OMO) as determined by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) of the Fed. The OMO mechanism involves central bank purchases and sales of government securities, such as treasury bonds or T-bonds. This action affects money supply and interest rates. Expansionary open market operations consist of Fed purchases of T-bonds. The Fed pays for T-bonds by printing new currency. When the Fed buys T-bonds from the public in the secondary bond market, an injection of cash occurs in the economy and in the banking system as bank reserves. Cash held by banks is called reserves. Through expansionary OMO, banks obtain more cash reserves to lend to business and household borrowers. Bank loans thus increase. When bank loans increase, the money supply in the economy also increases.

Banks earn interest income by lending to households and businesses. To increase the amount of loans, however, banks typically reduce interest rates to induce households and firms to borrow more funds for consumer spending, residential investment, and business investment. More bank loans lead to an expansion in business and residential investments as well as an increase in debt-financed consumer spending. Consequently, an expansionary or loose OMO policy creates higher macroeconomic demand in the form of higher consumer expenditure and more economic investment spending. RGDP accordingly rises and unemployment declines as macroeconomic demand goes up. This outcome of higher RGDP and lower unemployment is the main goal of loose monetary policy. A negative side effect of expansionary monetary policy is higher inflation. Inflation likely increases because of higher macroeconomic demand. Buyers are willing to pay higher product prices when demand increases.

In addition to an expansionary OMO, the central bank may sometimes adopt quantitative easing. This consists of Fed purchases of long-term private bonds to increase the money supply. For example, the central bank may print new cash to buy mortgage-backed securities. This has a similar effect on money supply and interest rates as an expansionary OMO. Central bank purchases of mortgage-backed securities create an injection of cash into the economy. Much of this new cash ends up as reserves in banks. These new bank reserves allow more bank loans to occur. Money supply therefore expands, and interest rates decline.

A contractionary or tight OMO has an opposite effect. A contractionary OMO policy consists of the Fed selling T-bonds to the public in the secondary bond market. The Fed receives money as it sells T-bonds to bond dealers. This action causes money to exit the economy into the vaults of the Fed. A leakage of money occurs from the economy and the banking system. Less cash or reserves are available in banks to lend to borrowers. Bank loans decline and money supply decreases.

This fall in money supply tends to drive up interest rates. A lower supply of money causes its price to rise, which is the interest rate. Higher interest rates create a contractionary demand effect on consumer spending and business investment. Higher interest rates make consumer and business borrowing more expensive. Debt-financed investment and consumption decrease. As aggregate demand falls, inflation goes down. Lower inflation is the goal of tight monetary policy. A negative side effect of a tight monetary policy is lower RGDP and higher unemployment. RGDP and unemployment likely worsen because of lower aggregate demand.

The characteristics of expansionary and contractionary monetary policies are summarized in Table 4.2.

Table 4.2 Expansionary and contractionary monetary policies

Type of monetary policy |

Loose policy |

Tight policy |

OMO |

Net purchase of T-bonds |

Net sale of T-bonds |

Effect upon bank reserves |

Increase in bank reserves |

Decrease in bank reserves |

Effect upon bank loans |

Increase in bank loans |

Decrease in bank loans |

Effect upon real money supply |

Increase in real money supply growth |

Decrease in real money supply growth |

Effect upon interest rates |

Decrease in interest rates |

Increase in interest rates |

Macroeconomic goals |

Higher RGDP, lower unemployment |

Lower inflation |

Macroeconomic side effect |

Higher inflation |

Macroeconomic slowdown, possible recession |

Macroeconomic problem that the policy addresses |

Recession or slow macroeconomic growth |

High inflation |

An important characteristic of the money supply process is the fractional reserve banking system. Money supply increases through the process of bank loans. When an individual or business borrows from a bank, the money supply goes up by the amount of the loan or the debt. This implies that a large portion of the money supply is related to the amount of private debt in the economy. Money creation through bank loans can create an economic vulnerability. Periodically, substantial bank loan defaults occur in the economy, such as the mortgage financial crisis of the Great Recession in 2007−2009. When a large amount of bank loan defaults occurs, the money supply declines proportionately. This adversely affects macroeconomic demand, GDP, and unemployment.

Monetary Policy Targeting of Inflation and Interest Rates

The central bank sets targets for inflation and interest rates (and other macroeconomic indicators) in determining monetary policy. The Fed tends to emphasize one or the other macroeconomic targets at different times. The monetary policy goal of inflation targeting focuses on the attainment of low, stable inflation. Inflation targeting is particularly applicable when the economy suffers from high inflation. In addition, the political right and classicalism often emphasize inflation targeting because of its implications for a stable business and financial environment. A stable, low inflation rate reduces financial risk, which enables market forces to flourish. Market forces operate more efficiently in a steady financial setting. This promotes stronger long-run economic growth.

The other main monetary policy objective is interest rate targeting. This strategy focuses on maintaining low and stable interest rates. Low interest rates reduce the cost of borrowing. This permits greater business and residential investment and higher consumer spending. Aggregate demand consequently rises. This leads to stronger RGDP growth and declining unemployment. The political left and Keynesianism tend to emphasize interest rate targeting, especially during episodes of macroeconomic slowdown.

Fiscal and Monetary Policy Coordination and Time Lags

Two additional issues are macroeconomic policy coordination and time lags in macroeconomic policy. The first issue is policy coordination. Depending on the macroeconomic preferences of the policymakers, the fiscal and monetary policies may reinforce each other. Alternatively, the two macroeconomic policies may conflict and could even offset each other.

The fiscal and monetary policies reinforce each other if the three macroeconomic policymakers agree on the policy direction. This occurs if the Fed, the president, and the Congress are unified on whether macroeconomic policies should be expansionary or contractionary. For example, a coordinated set of expansionary macroeconomic policies consists of tax cuts or higher government spending as determined by the president and the Congress combined with higher money supply growth and lower interest rates as adopted by the central bank.

Alternatively, the macroeconomic policymakers may disagree on the direction of stabilization policy. For example, Congress and the president may adopt an expansionary fiscal policy, while the Fed adopts a contractionary monetary policy. The two policies, in this instance, oppose each other. The net effect on the economy could consequently cancel out.

The other issue, besides policy coordination, is time lags for fiscal and monetary policies. Fiscal policy has a quicker impact than monetary policy. Tax cuts and higher government spending have a faster effect on the economy than higher money supply growth and lower interest rates.

Higher government spending or lower taxes impact RGDP and unemployment over a period of several months. Higher government spending directly causes higher GDP since government spending is a GDP component. Lower taxes also influence the economy relatively fast. The tax effect, however, is indirect. Lower income taxes directly influence disposable income. Higher disposable income then affects consumer spending, which is a component of GDP.

The effect of monetary policy on the economy, on the other hand, may require one year or longer to fully occur. Several linkages must take place over time for monetary policy. First, open market operations impact the amount of reserves held in banks. Higher bank reserves allow more bank loans to occur. The money supply rises as bank loans to businesses and households increase. Correspondingly, interest rates decline as money supply increases. Lower interest rates enable more consumer and business borrowing. Debt-financed consumer spending and business investment spending consequently expand. Finally, GDP increases and the unemployment rate falls.

1The discount rate and the reserve requirement also affect money supply and interest rates. These two instruments, however, are not the main tools of monetary policy.