As you’ve seen, a critical component of crafting a winning presentation is that, first and foremost, you must get your story right. Although a strong speaking voice, appropriate gestures, and skilled answers to challenging questions are important factors, none of them will yield a really powerful presentation unless your story is clear and leads your audience directly where you want them to go: your Point B.

Creating your presentation begins with the development of your story. Here is one of the first places where traditional methods of creating a presentation can go wrong.

Remember the MEGO syndrome? It strikes when Mine Eyes Glaze Over during a presentation that overflows with too many facts, all poured out without purpose, structure, or logic. When that happens, the presentation degenerates into a Data Dump: a shapeless outpouring of everything the presenter knows about the topic.

All too many businesspeople labor under the mistaken assumption that, for their audience to understand anything, they have to be told everything. As a result, they give extensive presentations that amount to nothing more than Data Dumps: “Let’s show them the statistics about the growth of the market. Then we’ve got the results of the last two customer satisfaction surveys. Throw in some excerpts from the press coverage we got after our product launch. Give them the highlights of our executive team’s resumes. And don’t forget the financial figures . . . the more, the better.” This is known as the Frankenstein approach: assembling disparate body parts.

The audiences to these Data Dumps are hapless victims. But sometimes the victims rebel. “And your point is?” and “So what?” are the all-too-common anguished interruptions of audiences besieged and overwhelmed by torrents of excessive words and slides. Those interruptions, however, are made more out of self-protection than rudeness. The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves.

Hopefully, you’ll never inflict a Data Dump on any of your audiences. But performing one is vital to the success of any presentation. The secret: The Data Dump must be part of your preparation, not the presentation. Do it backstage, not in the show itself. (The Greek word “obscene” originally described any theatrical action, such as a murder, that was kept offstage, out of the scene, because it was improper to display such behavior in public. In this sense, you can regard a Data Dump as literally obscene.)

What you need instead is a proven system to incorporate a thorough Data Dump into the development of your story. Brainstorming is that system. It’s a process that encourages free association, creativity, randomness, and openness while helping you consider all the information that may (or may not) belong in your presentation. Later on in the process, you can sort, select, eliminate, add, and organize these raw materials into a form that flows logically and compellingly from Point A to Point B. At the start, the key is not to apply logic to the materials, but simply to get them all out on the table, where they can be examined, evaluated, and sorted. Do the distillation before the organization: Focus before Flow.

To understand this approach, it’s important to consider the different processes and skills that go into the creative effort of developing a presentation. These are concepts drawn from my shared experiences with professional creative people in the media.

Scientists have long been fascinated by how different mental functions are centered in different areas of the human brain. Most of the higher brain activities occur in the cerebrum, which is divided into left and right hemispheres. According to most scientists, the left and right halves of the brain are responsible for different forms of reasoning. The left side controls logical functions and is associated with structure, form, sequence, ranking, and order. It tends to operate in a linear, first-one-thing-and-then-the-next fashion. The right side controls creative functions and is associated with concepts. It is essentially nonlinear in its operations. The right brain bounces around among concepts, following connections that are impossible to explain logically.

Building a presentation is a creative process. That means starting with the right brain.

Here’s the problem: Most presenters, when developing their stories, tend to apply a left-brain approach to what is really a right-brain process. They try to jump immediately to a logical, structured, linear end product when their right brain is still caroming in nonlinear mode.

Why? Because businesspeople are results-oriented rather than process-oriented. I’m sure that you, like most businesspeople, are quite process-oriented when it comes to critical matters such as long-term strategy, product design, or problem-solving, but these are all subjects for off-site meetings. Backstage!

When it comes to results-oriented tasks, such as developing a presentation to a very important audience (front and center stage), you are eager to get there in the shortest distance between two points. You think that a time-consuming process might delay the result. But if you choose a left-brain process while your right brain is free-associating, you’ll wind up traversing that seemingly short distance between points over and over and over again. You’ll end up spinning your wheels and spilling out a Data Dump.

The solution is timing. It’s not a matter of more time; it’s about the proper use of time. Get the sequence right: Let the right brain complete its stream-of-consciousness cycle before applying the left brain’s structure. Focus before Flow.

Let the right brain complete its stream-of-consciousness cycle before applying the left brain’s structure.

A vivid illustration of the distinct difference between right and left brain functioning is spoken language. Speech reflects how the right brain operates in its spontaneity, in its grammatical and syntactical messiness, and in its frequent logical leaps.

Let’s illustrate with an excerpt from the live presidential debate between then-Governor George W. Bush of Texas and Vice President Al Gore. The debate, in a town hall format, took place on October 17, 2000, and PBS anchor Jim Lehrer was the moderator. Each candidate was given a chance to respond to questions posed by ordinary citizens. Here is Governor Bush’s response to the following question: “How will your tax proposals affect me as a middle-class 34-year-old single person with no dependents?”

You’re going to get tax relief under my plan. You’re not going to be targeted in or targeted out. Everybody who pays taxes is going to get tax relief. If you take care of an elderly in your home, you’re going to get the personal exemption increased.

I think also what you need to think about is not the immediate, but what about Medicare? You get a plan that will include prescription drugs, a plan that will give you options. Now, I hope people understand that Medicare today is—is—is important, but it doesn’t keep up with the new medicines. If you’re a Medicare person, on Medicare, you don’t get the new procedures. You’re stuck in a time warp, in many ways. So it will be a modern Medicare system that trusts you to make a variety of options for you.

You’re going to live in a peaceful world. It’ll be a world of peace, because we’re going to have clearer—clear-sighted foreign policy based upon a strong military, and a mission that stands by our friends—a mission that doesn’t try to be all things to all people. A judicious use of the military which will help keep the peace.

You’ll be in a world, hopefully, that’s more educated, so it’s less likely you’ll be harmed in your neighborhood. See, an educated child is one much more likely to be hopeful and optimistic. You’ll be in a world in which—fits into my philosophy, you know, the harder work—the harder you work, the more you can keep. It’s the American way.

Government shouldn’t be a heavy hand. That’s what the federal government does to you. Should be a helping hand. And tax relief in the proposals I just described should be a good helping hand.[1]

Remember (if you still can) that the original question had to do with how a 34-year-old single person with no dependents would be affected by the candidates’ competing tax plans.

The response given by Governor Bush (soon to be President Bush) veered and rambled all over the place. He never specifically addressed the question of how a 34-year-old single person would be affected by his tax plan . . . except at the very beginning of his ramble with a broad, general assertion: “You’re going to get tax relief under my plan,” which didn’t explain how much relief or what kind.

Governor Bush began by talking about offering an increased tax exemption to those who care for “an elderly,” forgetting or ignoring the fact that the person who asked the original question specified that she had no dependents.

Next, he skipped to Medicare (a subject of less-than-immediate interest to a 34-year-old). Then he skipped further off the path on to the topics of world peace, military policy, education, and, finally, work ethic.

Six subjects later, in his last sentence, probably recalling that the original question dealt with taxes, Governor Bush belatedly referred again to “tax relief in the proposals I just described,” skimming over the fact that he never did describe any tax proposals.

This is not meant to pick on George W. Bush. Some of our most effective political leaders have been known to speak in a rambling fashion (Dwight D. Eisenhower, for one). And, speaking crisply and logically is no guarantee of statesmanship or political wisdom. Depending on your own political views and personal tastes, you might find Bush’s speaking style infuriating, comic, or refreshingly human.

The essential point is a more general one. An excerpt of spoken language, when transcribed and printed, will never read like well-crafted prose. As a personal example, I recently recorded myself during a program with my clients, delivering the same material I’ve delivered for two decades. When I read the transcription, I was surprised to see how irregular my word patterns were. The reason: Spoken language is governed by the right brain. Rather than focusing on the rules of logic, grammar, syntax, and consistency, the mind flows freely, wherever the concepts lead.

By contrast, the production of written language tends to be governed by the left brain. When most people sit down to write a letter, memo, or report, their minds are front-loaded with those left-brain functions: logic, grammar, spelling, and punctuation. Rather than bouncing freely from one idea to the next, considering names, references, and concepts that may or may not be clearly developed, they move methodically through a sequence of points, meticulously self-correcting their syntax and logic as they go.

The result is a document that is technically correct. It doesn’t contain fractured sentences like George W. Bush’s “You’ll be in a world in which—fits into my philosophy, you know, the harder work—the harder you work, the more you can keep,” or repetitions like his “Now, I hope people understand that Medicare today is—is—is important.”

If the writer’s thinking is being ruled by the left brain, the natural flow of concepts is often impeded. As a result, the ensuing document almost inevitably omits ideas that are necessary or, worse, includes ideas that are unnecessary, overly detailed, or irrelevant.

You’ve probably written documents this way yourself: sitting down cold at your keyboard and banging out an email, memo, or letter, “editing” it for style and content on-the-fly. If so, you may have had the experience of reading the document afterward and discovering that you’d completely forgotten to mention an important fact or idea, or you may have stuck in a completely irrelevant detail. This is a natural by-product of left-brain dominance.

Developing a presentation by starting with left-brain considerations such as logic, sequence, grammar, and word choice (or, for that matter, the color, style, and design of slides) is ineffective. Crafting a presentation is a creative task, and it must start with the resources that are available only on the right side of your brain. Use the right tool for the right job.

Crafting a presentation is a creative task, and it must start with the resources that are available only on the right side of your brain.

Therefore, begin your story development process by doing what your brain is going to do anyway: follow the stream of consciousness, and capture the results during Brainstorming.

When you start to Brainstorm about your very important presentation to your very important client, do you want to start by thinking about what you’ll wear? I doubt it. Do you want to start by thinking about the rest of your schedule on the day of your important presentation? I don’t think so. Attire and calendar are related to the presentation, but only peripherally. You needn’t include them in your Brainstorm.

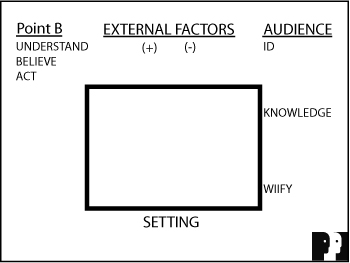

Before you begin the Brainstorming process, you must first tighten your focus past the peripherals. To do this, begin with a tool called the Framework Form.

Think of your presentation as a blank canvas within a frame. This is where you will do your Brainstorming. To tighten the focus, you need to set the outer limits, the parameters, of your presentation. They include the following elements.

Since most presentations lack a clear point (the first of the Five Cardinal Sins), why not start with it? In other words, start with the objective in sight, and work toward it. Here again, this rule incorporates the wisdom of Aristotle and Stephen R. Covey.

Now that you appreciate the importance of Audience Advocacy, you must analyze what your intended audience knows and what they need to know to understand, believe, or act on what you are asking. Use the following three metrics to analyze your audience:

-

Identity. Who will be in the audience? What are their roles?

-

Knowledge level. Remember that one of the Five Cardinal Sins is being too technical. You cannot be an effective audience advocate unless you know your audience and are prepared to communicate with them in language they understand. Therefore, it’s important to spend time during your preparation process analyzing your audience and anticipating what they know and what they don’t know.

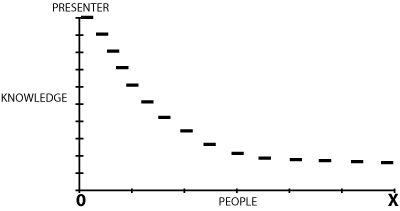

As a tool for assessing your audience’s knowledge level, I’ve developed a simple, nonscientific chart, called the comprehension graph. It measures knowledge along the vertical axis, from zero (no background knowledge about the presentation topic) to the maximum (knowledge that usually only the presenter would have). The horizontal axis measures the number of people in the audience.

To use this graph, mark points along it that represent what fraction of your audience will be located at each knowledge level along the vertical axis. For example, for a presentation about a new high-tech product to an audience that includes a large number of relatively unsophisticated listeners, along with a handful of engineers and other knowledgeable experts, the graph might look like Figure 3.1.

The specific shape of the line you draw should be in your mind constantly as you prepare and present your material. If only a few members of your audience share your level of technical or industry knowledge (as is often the case), you can’t fly too high for too long. You need to put significant effort into translating your technical information, using language, examples, and analogies that everyone can understand.

When technical terms are unavoidable, you can raise the audience’s knowledge level through the use of parenthetical expansion. Simply stop your forward progress and explain your complex concepts and terminology by parenthetically adding, “By that I mean . . . ” and then going on to offer a clear and simple definition.

-

The WIIFY. This is undoubtedly the most important factor in analyzing your audience. Remember that another of the Five Cardinal Sins is no clear benefit to the audience. Ask yourself: What does your audience want? How does the subject of your presentation offer it to them? How can you make the benefits to your audience crystal clear?

External factors are conditions that are “out there,” in the world, independent of you and your audience. They can impact your message and how it may be received. Some external factors are positive, and some are negative. For instance, when making a pitch for investment dollars for your company, a rapidly expanding market for your product would be a positive external factor, while the emergence of powerful new competitors would be a negative external factor. You must consider all the external factors as you prepare your presentation. In some cases, you may need to change the content of your presentation or alter its structure to respond to unusually powerful factors. Be sure that you include counterpoints to the negative factors.

Throughout the preparation process, keep in mind the physical setting for your presentation. These factors, too, may affect the content of your presentation. You can analyze the setting by asking and then answering these classic journalistic questions:

-

Who? Will you be the only presenter? If not, how many others will be presenting before and after you? How will you distribute the parts of the story among the presenters?

-

When? When will you be making the presentation? How much time will you be allotted? Will you have time for audience interaction? Will there be a question-and-answer period?

-

Where? Will you be meeting in your company’s offices, on your audience’s turf, or in some neutral setting? How will the room be arranged? Will it be an intimate or massive setting? In a larger setting, where only you will have a microphone, it’s likely you’ll give the entire presentation uninterrupted. In a smaller setting, interruptions are inevitable. If so, allow time for discussion.

-

What? What kind of audiovisual aids will you be using? Will you be doing a demonstration to show your product in action? If so, will there be room and visibility to perform the demo? When will you do the demo: before, during, or after the presentation?

You must determine all these factors and define them in your Framework Form before you start your Brainstorming. Use the Framework Form shown in Figure 3.2 to assemble and capture all the preceding information as you develop it.

Figure 3.2. The Power Presentations Framework Form. (You can download a copy of this form by visiting our website, www.powerltd.com.)

Define all these factors as clearly and as specifically as possible. There is no such thing as a one-size-fits-all presentation. Build a presentation tailored to one audience, on one occasion, presented by one set of presenters, conveying one story, with one purpose. A presentation that is not custom-built will inevitably be less effective and less likely to persuade. Why bother presenting at all if you are not prepared to invest the time needed to make your presentation all that it can be?

Does this mean that you need to start every presentation from scratch? Not necessarily. After you’ve done the process once, the second time will be much shorter, and shorter still for each succeeding iteration. In the 20 years I’ve been in business, the process has never taken me more than an hour and a half the first time with a client, regardless of the subject, from the most complex biotech company to the simplest retail story. It usually takes 15 minutes the second time, and less each time thereafter.

Eventually, you’ll be able to click and drag parts of one presentation into another. The key is to develop each presentation by starting with the basic concepts of the Framework Form. This initializing process will help ensure that each presentation you make is effectively focused on each persuasive situation you face.

Resist any temptation to skip or short-circuit the Framework Form process. Don’t take it for granted that everyone in your group knows and understands the mundane who-what-when-where-why details of your presentation. Lay out these facts in advance; they will have a positive impact on what should and should not appear in your presentation, and in what form.

Now that you’ve set the context and focus, you’re ready to begin developing potential concepts. Now your right brain, rather than thinking about attire or schedule, can focus on more relevant ideas. You’ll want to capture those ideas as they emerge, and that’s where we turn to Brainstorming.

Here’s how to do productive Brainstorming:

-

Set up a large whiteboard or an easel with a big pad of paper and lots of pushpins to mount the sheets. I prefer a whiteboard because it allows me to erase and rewrite free-flowing ideas at will. It also results in a neater and easier-to-read set of Brainstorming notes. Have on hand a supply of markers in several colors. Use different colors to indicate different groups or levels of ideas.

There are several high-tech products on the market that can capture written scrawls electronically from a whiteboard to a computer and then to a printer. (I use eBeam, www.e-beam.com.) These tools are very cool, but not essential. You can always ask someone to hand-copy the notes during or after the Brainstorming.

-

Gather your Brainstorming team. It should include all those who will participate in the presentation, as well as any others who have ideas or information to contribute.

-

You, as the presenter, or someone from your group (with reasonably neat handwriting) should handle the markers and capture the Brainstorming ideas on the whiteboard. This person is your scribe. In my programs with my clients, I act as both scribe and facilitator. As a facilitator, I assume a neutral point of view and simply take down all ideas as they come up, without judgment. There are no bad ideas in Brainstorming. Let them all flow. That is the essence of right-brain thinking. I also ask that each person in the group feed his or her ideas through me so as not to lose any ideas in side discussions, crosstalk, or digressions. I post all the ideas on the whiteboard for all to see and share.

Have your scribe assume a similar role. Your scribe should not have a bias for or against any idea that emerges. Consider your scribe as Switzerland: neutral in all events.

-

Launch the Brainstorming session by having someone, anyone, call out an idea about something that might go into the presentation. One person might say “Management.” You or your scribe should write the word “Management” on the whiteboard and then draw a circle around it to turn that concept into a self-contained nugget.

-

As each concept comes up, the entire group should help to explode the concept. For example, once “Management” appears on the whiteboard, pop out whatever ideas come to mind that are related to management. For example, there are the various members of your company’s top management team: the CEO, the chairman, the CFO, the executive vice president. You or your scribe should jot these down as they come up, circle them, and link the circles to form a cluster of related ideas. Call the major idea in a cluster the “parent” and the subordinate ideas connected to it the “children.”

-

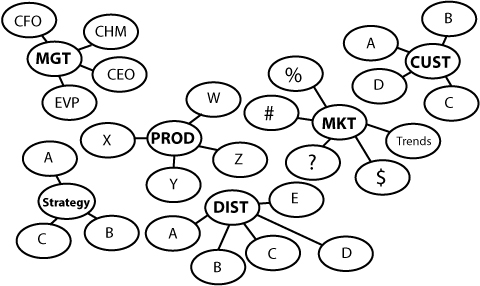

Continue to do the same for other concepts that people in the group suggest. Certain concepts come up in almost every business presentation: “Our Products,” “Our Customers,” “Market Trends,” and “The Competition.” Depending on the specific purpose of your presentation and the issues your company is currently facing, some concepts will be unique to your presentation. As you work, you’ll gradually fill the whiteboard with related concepts that might look something like Figure 3.3.

-

As you work, be flexible! Don’t be afraid to bounce from concept to concept as necessary. While the group is exploding the concept of “Marketing Plan,” someone might interject, “Oops! We forgot to list Jim, the marketing vice president, as a member of the management team.” No problem; squeeze Jim in on the whiteboard. If necessary, use the eraser.

Someone else might say, “There’s a market statistic I’d like to include, but I’m not sure the latest data is available.” No problem; note the idea wherever it belongs with a question mark in the circle. The placeholder will remind you that further research is needed.

As the Brainstorming proceeds, you’ll find that ideas pop up all over the place. The ideas will shift, connect, disconnect, and duplicate as they seek relationships with other ideas. This is your right brain at work. As ideas continue to come up, they will move around. Let it happen. Relationships will emerge, change, and develop. Capture all the activity on the whiteboard.

While your team is Brainstorming, the right brain must rule. Remember that most businesspeople are left-brain-oriented, conditioned by education and experience to apply logic, reason, and rules to every activity. Learn to stifle this tendency during your Brainstorming. Avoid wordsmithing ideas. If you get bogged down in debating the proper words, you’ll impede the free flow of fresh concepts. It’s hard to avoid wordsmithing at first, but you’ll find it surprisingly liberating.

Remember: There are no bad ideas in Brainstorming. Avoid censoring any ideas. The person whose idea is rejected is likely to feel rebuffed and may become reluctant to offer other ideas. When anyone mentions a new idea, jot it somewhere on the whiteboard, even if it strikes others as trivial or irrelevant. Even a seemingly needless idea can be useful, since it may stimulate someone else to bring up a related fact that may turn out to be important. Get it all down. Don’t worry about recording too much information; not everything on the whiteboard will end up in your presentation. Consider all ideas during Brainstorming as candidates, not finalists. The right time to do the Data Dump is during your preparation . . . and not during your presentation!

Avoid thinking about structure, sequence, or hierarchy. If you find yourself wanting to say, “That idea should go up front” or “That idea should close the presentation” while other ideas are popping up, it would be like trying to rub your stomach and pat your head at the same time. Structuring front-loads your mind with sequence, order, and linear thinking, the hallmarks of your left brain. Instead, let the concepts tumble out in nonlinear fashion, just the way the synapses of your brain fire naturally. Think about structure later. Remember: Focus before Flow.

Give yourself enough time to do a thorough Data Dump. Don’t put down your markers the first time there’s a long pause in the conversation. Chances are the group is just taking a mental breather. Most Brainstorming sessions feature two or three “false finishes,” each followed by an explosion of new ideas, before the group has really exhausted its store of information and ideas.

When you are truly done, your whiteboard will be filled with lots of circles. At that point, the entire group will be able to see all the elements of your story, all the candidate ideas, laid out for easy examination and organization.

If any of this sounds familiar, it should: It is the kind of out-of-the-box thinking that many businesspeople use in strategic planning, product development, or problem-solving sessions. Well, these are the very same minds and the very same subject matter that go into a presentation. Why not use the same process?

One of the benefits of Brainstorming is that it provides a panoramic view. It’s like spreading out all the parts of a kid’s bicycle before you start trying to follow the all-too-complicated assembly directions; or the way a chef lays out all the ingredients for a complicated dish before the cooking begins in what’s called a mise en place. Spreading out the raw materials of your presentation gives you ready access to and control of all your ideas.

Contrast this approach with a left-brain, linear process. The typical left-brain method is to start by designing Slide 1: “Okay, we’ll open with our company mission statement”; then Slide 2: “Now let’s talk about the management team”; then Slide 3: “Now the statistics about the marketplace”; and so on. The problem with this approach is that, as you focus on the slides one by one, each slide effectively covers and hides the slide before. As a result, you’re looking at only one concept at a time. You never see the whole story at once; therefore, you never see all the components organized into a few key high-level units.

Instead, the Brainstorming approach follows the right brain’s natural functions. It allows your ideas to pour out in a random, nonlinear fashion, ensuring that every relevant concept (as well as every irrelevant one) gets a place on the radar screen. Later, you’ll enlist the help of the left brain in bringing order to the raw materials you’ve generated.

Brainstorming generates a host of ideas of varying importance, loosely related to one another. The first step in getting from this relative chaos to an organized, clearly focused presentation is a technique known as Clustering.

Actually, we’ve already used Clustering to a degree. In the previous group Brainstorming example, every time the group exploded a concept into a series of related concepts, forming a group of linked circles on the whiteboard, they created a cluster. These clusters reflected the natural relationships among the ideas as they poured out during Brainstorming: parents and children.

Clustering is a necessary technique for organizing any complex material for presentation to an audience. It’s also an ancient concept, dating back to the classic rhetoricians of Greece and Rome.

There’s a story, probably apocryphal, about a Roman orator whose memory was legendary. (It may have been Cicero, although the documentation is sparse.) The orator often spoke in the Roman Forum extemporaneously for hours, without referring to a single note. His secret was a memory technique that is still used today. We can imagine him explaining it to a curious admirer in a dialogue like this: “You asked me how I can speak coherently at length, without written notes. Did you notice today how I walked around the Forum as I spoke?”

“Indeed I did. I assumed you did so in order to reach out to those in every corner of the audience.”

“In part,” replied the orator. “But there was a more important reason. As I walked from point to point around the edges of the Forum, I paused for a time at six different marble columns. Those columns are my memory aids. Each one symbolizes and reminds me of one group of ideas. Thus, rather than memorizing dozens of particular details, I have to recall only the six key ideas. Each of those key ideas evokes the details related to it.”

Did Cicero really use this technique 2,000 years ago? No one knows for sure. But today I urge my clients to use the same technique to distill the ideas in their presentations. Clustering lets you reduce the 40 or 50 ideas that fill your whiteboard to five or six Roman Columns, the key ideas that organize all the rest. Each column has a group of subordinate ideas. Now instead of trying to organize many ideas at the detail level, you can organize them at the 35,000-foot level.

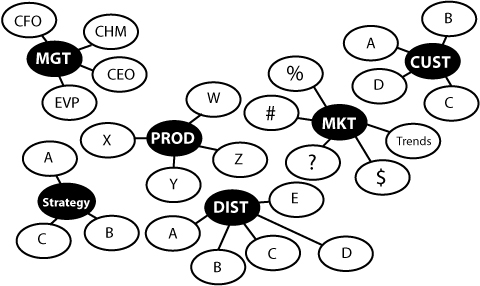

When you look at your whiteboard filled with ideas, you will find key clusters emerging from the chaos. Examine the whiteboard, and use a new marker color to highlight the most significant ideas. The idea is to make the parents stand out visually from the mass of data, as shown in Figure 3.4.

As your group works on identifying clusters, you may find yourselves identifying links and connections that didn’t occur to you before. That’s fine; just draw lines on the board as needed, or erase and redraw the circles and lines as necessary. You may find yourself shifting concepts around: “Say, doesn’t that point about the changing demographics of our market belong with ‘Key Trends’ rather than with ‘Sales Potential’?” “How about connecting ‘Cost Savings’ to ‘Customer Benefits’ instead of to ‘Unique Product Features’?” No problem; move the children and link them to the most appropriate parent.

If some ideas seem to have no connection to any of your Roman columns, now is the time to ask whether those ideas are truly relevant and necessary. Perhaps they don’t deserve to survive the transition to the finished presentation. And if you think of new ideas that should be inserted, go ahead and add them. That’s all part of the process.

As you can see, the technique of Clustering begins the process of organizing and introducing logic into the presentation. After having deliberately held back your left brain, you can now let it begin to get into the act.

You may be tempted to short-circuit the process by skipping the Brainstorming stage. “Why not start with clusters of key ideas?” you might say. “I could probably sit down right now and list the five main points we need to emphasize. That would save us all a lot of time.” That’s your logical left brain speaking. It wants to avoid the messy, uncontrolled process of free association. But the human mind doesn’t work that way.

Start by unloading a “Splat!” of ideas in whatever order they came out, free-form . . . a total Data Dump. Organize them later, and later still polish them into words and sentences and paragraphs and, ultimately, into slides. This process is called Splat and Polish.

In my many years in the media, I’ve learned that most professional writers . . . novelists, journalists, playwrights, technical writers, and historians . . . follow this same process. Not one of them will write a single page of text until they’ve done their research, brooded over their topic, and assembled a mass of notes about it. They may note their ideas on Post-its, on dog-eared index cards, in spiral-bound notebooks, or simply in stacks of loose pages. Those notes, of course, are their Data Dump.

Results-oriented businesspeople, unfortunately, don’t use the same process when creating a presentation or, for that matter, when writing a report, a speech, or a memo. That’s the way businesspeople are accustomed to thinking: Get to the endpoint as quickly as possible. Find the shortest distance between two points. They figure that the quickest way to get a presentation done is to just start writing. Logical, yes? Yes, and wrong.

Here’s a story that illustrates the pitfalls that the Splat and Polish approach can help you avoid:

Judy Tarabini (now McNulty) was a vice president in the technology unit of the Hill and Knowlton Public Relations Agency when Ben Rosen, continuing his promise to help me grow my business, introduced me to the firm. After I delivered my program successfully to one of Judy’s clients, she began to call on me regularly for her other clients.

In 1993, Judy joined the corporate communications department of Adobe Systems. It wasn’t long before she called on me to work with Adobe. This time she had a high-level, mission-critical presentation: Adobe was about to introduce its Acrobat product, and they were planning to have their entire senior management team, about 15 strong, fan out into the market to make launch presentations. Judy was so positive about my program, she convinced Adobe’s entire senior management team, including the founding chairman and CEO, John Warnock, and his cofounding partner and president, Chuck Geschke, to participate in a story development session with me.

As always, we started with a blank slate. I stepped up to the immaculate whiteboard in the amply appointed executive conference room at Adobe’s then-brand-new corporate headquarters in Mountain View. (They have since moved to even newer and more advanced facilities in San Jose.)

I started drawing out the executives. We began with Point B, we continued on to the WIIFY, then we moved on to the Brainstorming. As those very bright and very high-powered people spouted their thoughts, I raced to capture them on the whiteboard. We got lots of clusters: the Acrobat rollout schedule, the distribution plan, the Acrobat partners, the product benefits, the market, and many more. Before long, the whiteboard was filled to the edges with clusters of ideas.

Then there was a pause. I looked around the room and said, “Please take a moment and look at all the clusters on the whiteboard. Tell me whether we need to alter any of the ideas, whether we need to consider shifting associations, or whether we’ve omitted anything.”

A thoughtful silence ensued. Then suddenly, reverberating in the silence, there was a sharp thwack! Chuck Geschke had slapped his palm against his forehead, as in the “I should’ve had a V8!” television commercials. Then he broke into a sheepish grin and said, “We’ve left out what Acrobat does!”

Does that sound odd? Sure it does. But it happens a lot. You’re so close to your business that it’s easy to take key ideas for granted, or to overlook or forget about concepts that are second nature to you but unfamiliar to your audience. That’s one huge reason why you should never try to end-run the Brainstorming process and rush past story development. Take the time to make certain that everything (and that means everything) that may be relevant has had a chance to surface. Realizing what you omitted five minutes before the start of your presentation will be too late!

Notice that so far I’ve held off any discussion about selecting the sequence of ideas for your presentation, which is the left-brain process. First, get the heart of your story straight; then and only then can you think about the most effective sequence of concepts for presenting that story persuasively. In developing your presentation, keep the proper order of the creative process in mind: Focus before Flow.

Now, having set the context with the Framework Form, having poured out all the concepts that might be relevant to your presentation by Brainstorming (an efficient Data Dump), and having condensed those concepts and ideas by Clustering, you’re ready to develop the flow of ideas that will guide your presentation. That’s the topic of the next chapter.