1

Introduction

This practice guide describes a process-based approach to project management. The framework for this approach is based on the five Project Management Process Groups:

▶Initiating. Those processes performed to define a new project or a new phase of an existing project by obtaining authorization to start the project or phase.

▶Planning. Those processes required to establish the scope of the project, refine the objectives, and define the course of action required to attain the objectives that the project was undertaken to achieve.

▶Executing. Those processes performed to complete the work defined in the project management plan to satisfy the project requirements.

▶Monitoring and Controlling. Those processes required to track, review, and regulate the progress and performance of the project; identify any areas in which changes to the plan are required; and initiate the corresponding changes.

▶Closing. Those processes performed to formally complete or close the project, phase, or contract.

The Process Groups are independent of the development approach (i.e., predictive, adaptive, agile, or hybrid), application area (e.g., marketing, information services, accounting, etc.), and industry (e.g., construction, aerospace, telecommunications, pharmaceuticals, etc.) but are intended for practitioners who primarily follow a predictive or waterfall approach. This practice guide describes the 49 processes within these five Process Groups along with the inputs, tools and techniques, and outputs associated with those processes.

This practice guide identifies the processes that are considered good practices on most projects, most of the time. Project management should be tailored to fit the needs of the project. There is no requirement that any particular process or practice be performed. The processes should be tailored for the specific project and/or organization. Specific methodology recommendations are outside the scope of this practice guide.

1.1 PROJECT MANAGEMENT

Project management is the application of knowledge, skills, tools, and techniques to project activities to meet project requirements. Project management is accomplished through the appropriate application and integration of the project management processes identified for the project.

Managing a project typically includes but is not limited to the following activities:

▶Identify project requirements.

▶Address the various needs, concerns, and expectations of stakeholders.

▶Establish and maintain active communication with stakeholders.

▶Execute the work required to deliver the project outcomes.

▶Manage resources.

▶Balance the competing project constraints, which include but are not limited to scope, schedule, cost, quality, resources, and risk.

Project circumstances will influence how each project management process is implemented and how the project constraints are prioritized.

1.1.1 IMPORTANCE OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT

Project management enables organizations to execute projects effectively and efficiently. Effective project management helps individuals, groups, and public and private organizations to:

▶Meet business objectives.

▶Satisfy stakeholder expectations.

▶Be more predictable.

▶Increase chances of success.

▶Deliver the right products at the right time.

▶Resolve problems and issues.

▶Respond to risks in a timely manner.

▶Optimize the use of organizational resources.

▶Identify, recover, or terminate failing projects.

▶Manage constraints (e.g., scope, quality, schedule, costs, resources).

▶Balance the influence of constraints on the project (e.g., increased scope may increase cost or schedule).

▶Respond to rapidly evolving markets.

▶Manage change using a controlled process.

Poorly managed projects or the absence of project management may result in:

▶Missed requirements,

▶Missed deadlines,

▶Cost overruns,

▶Poor quality,

▶Rework,

▶Waste,

▶Uncontrolled expansion of the project,

▶Loss of reputation for the organization,

▶Unsatisfied stakeholders, and/or

▶Failure in achieving the objectives for which the project was undertaken.

1.1.2 FOUNDATIONAL ELEMENTS

The foundational elements that are essential for working in and understanding the discipline of project management are:

▶Project. A temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result. (See Section 1.2 for additional information.)

▶Program. Related projects, subsidiary programs, and program activities that are managed in a coordinated manner to obtain benefits not available from managing them individually. (See Section 1.3 for additional information.)

▶Program management. The application of knowledge, skills, and principles to a program to achieve the program objectives and obtain benefits and control not available by managing program components individually. (See Section 1.3 for additional information.)

▶Portfolio. Projects, programs, subsidiary portfolios, and operations managed as a group to achieve strategic objectives. (See Section 1.4 for additional information.)

▶Portfolio management. The centralized management of one or more portfolios to achieve strategic objectives. (See Section 1.4 for additional information.)

▶Relationship of project, program, portfolio, and operations management. Projects may be managed in three separate scenarios: as a stand-alone project that is outside of a program or portfolio, within a program, or within a portfolio. (See Section 1.5 for additional information.)

▶Operations management. The ongoing production of goods and/or services. It ensures that business operations continue efficiently by using the optimal resources needed to meet customer demands. It is concerned with managing processes that transform inputs (e.g., materials, components, energy, and labor) into outputs (e.g., products, goods, and/or services).

Operations management is an area that is outside the scope of formal project management as described in this practice guide.

▶Operations and project management. Ongoing operations are outside of the scope of a project; however, there are intersecting points where the two areas cross. (See Section 1.6 for additional information.)

▶Organizational project management (OPM). A framework in which portfolio, program, and project management are integrated with organizational enablers in order to achieve strategic objectives. (See Section 1.6 for additional information.)

1.2 PROJECTS

A project is a temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result. Projects are undertaken to fulfill objectives by producing deliverables that result in the desired outcomes. An objective is defined as an outcome toward which work is to be directed, a strategic position to be attained, a purpose to be achieved, a result to be obtained, a product to be produced, or a service to be performed. A deliverable is defined as any unique and verifiable product, result, or capability to perform a service that is required to be produced to complete a process, phase, or project. Deliverables may be tangible or intangible.

The temporary nature of projects indicates that a project has a definite beginning and end. Temporary does not necessarily mean a project has a short duration. The end of the project is reached when one or more of the following is true:

▶The project's objectives have been achieved.

▶The objectives will not or cannot be met.

▶Funding is exhausted or no longer available for allocation to the project.

▶The need for the project no longer exists (e.g., the customer no longer wants the project completed, a change in strategy or priority ends the project, the organizational management provides direction to end the project).

▶The human or physical resources are no longer available.

▶The project is terminated for legal cause or convenience.

1.2.1 PROJECTS DRIVE CHANGE

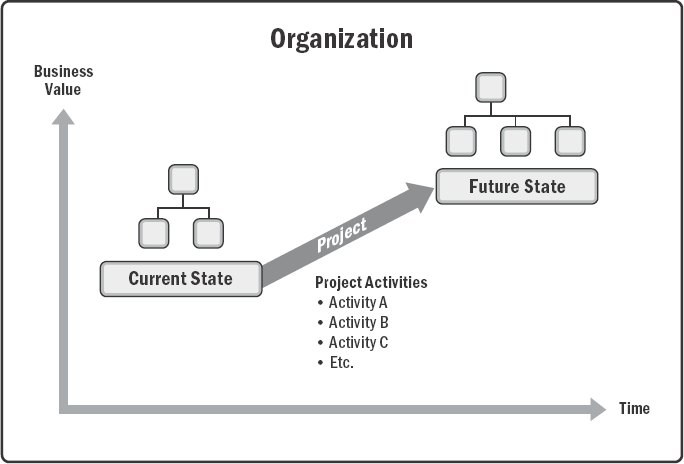

Projects drive change in organizations. From a business perspective, a project is aimed at moving an organization from one state to another state in order to achieve a specific objective (see Figure 1-1). Before the project begins, the organization is commonly referred to as being in the current state. The desired result of the change driven by the project is described as the future state.

The successful completion of a project results in the organization moving to the future state and achieving the specific objective.

Figure 1-1. Organizational State Transition via a Project

1.2.2 PROJECTS ENABLE BUSINESS VALUE CREATION

PMI defines business value as the net quantifiable benefit derived from a business endeavor. The benefit may be tangible, intangible, or both. In business analysis, business value is considered the return, in the form of elements such as time, money, goods, or intangibles in return for something. Business value in projects refers to the benefit that the results of a specific project provide to its stakeholders. The benefit from projects may be tangible, intangible, or both.

1.2.3 CONTEXTS FOR PROJECT INITIATION

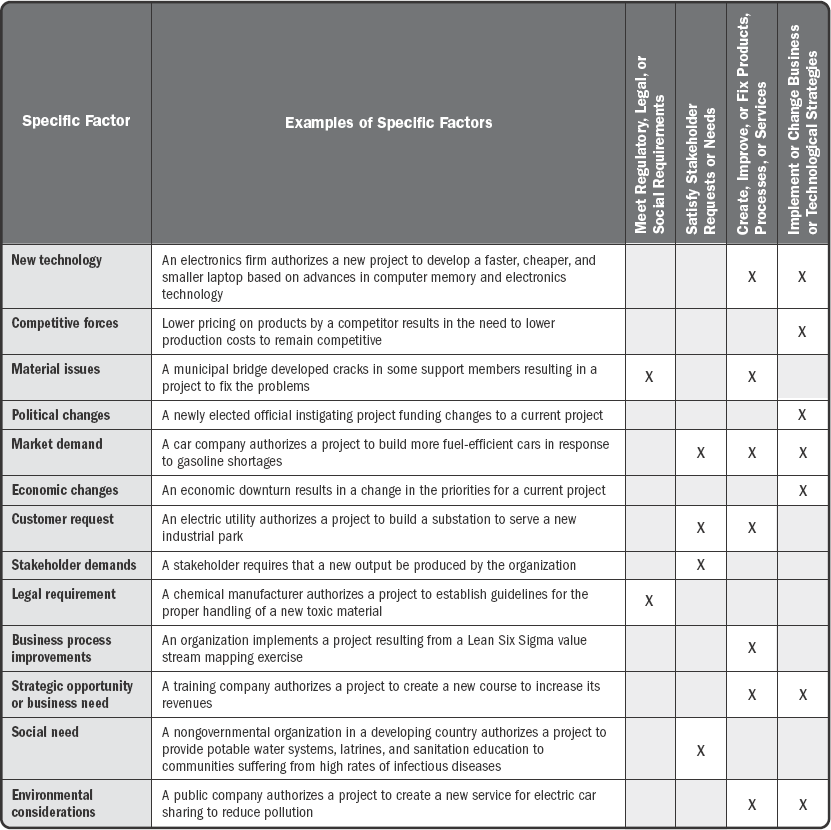

Organizational leaders initiate projects in response to factors acting upon their organizations. Projects provide the means for organizations to successfully make the changes necessary to deal with these factors. There are four fundamental categories for these factors, which illustrate the context of a project:

▶Meet regulatory, legal, or social requirements;

▶Satisfy stakeholder requests or needs;

▶Create, improve, or fix products, processes, or services; and

▶Implement or change business or technological strategies.

These categories should map directly to the strategic objectives of the organization and projects will fulfill the objectives and, ultimately, deliver business value. Examples of factors that lead to the creation of a project are shown in Table 1-1.

Table 1-1. Factors that Lead to the Creation of a Project

1.3 PROGRAMS AND PROGRAM MANAGEMENT

A program is defined as related projects, subsidiary programs, and program activities managed in a coordinated manner to obtain benefits not available from managing them individually. Programs include program-related work outside the scope of the discrete projects in the program. Program management is the application of knowledge, skills, and principles to a program to achieve the program objectives and obtain benefits and control not available by managing related program components individually. Programs may also include work that is operational in nature.

Program management supports organizational strategies by authorizing, changing, or terminating projects and managing their interdependencies.

1.4 PORTFOLIOS AND PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT

A portfolio is defined as projects, programs, subsidiary portfolios, and operations managed in a coordinated manner to achieve strategic objectives. Portfolio management is the centralized management of one or more portfolios to achieve strategic objectives. Portfolio management focuses on ensuring the portfolio is performing consistent with the organization's objectives and evaluating portfolio components to optimize resource allocation. Portfolios may include work that is operational in nature.

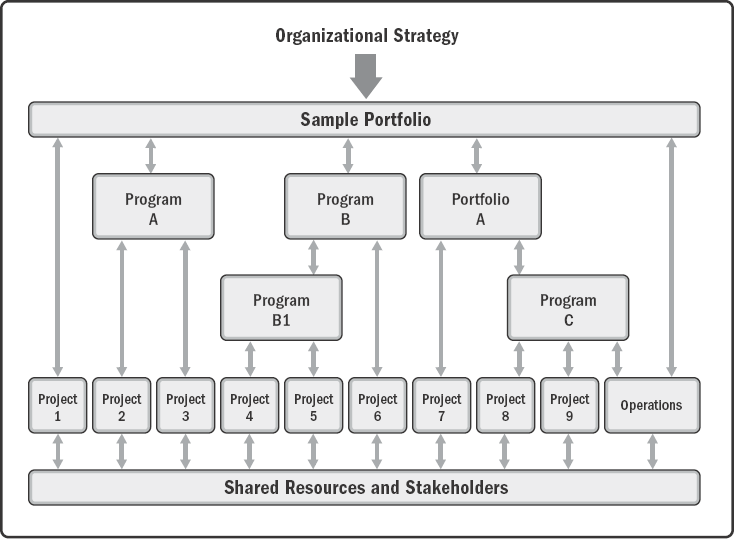

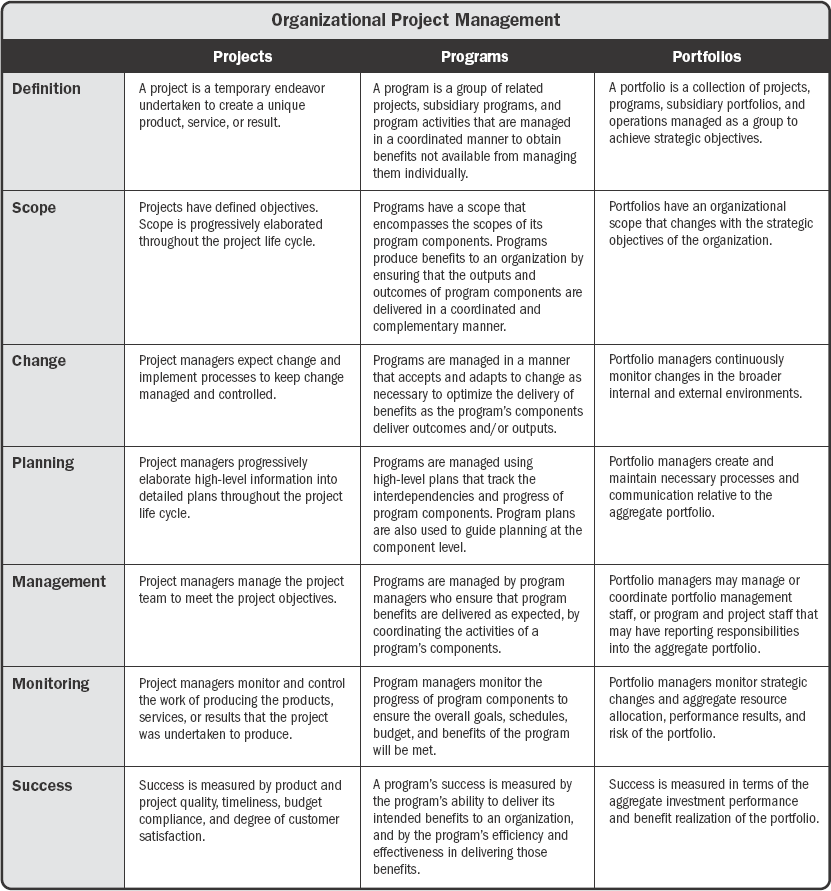

1.5 RELATIONSHIP AMONG PORTFOLIOS, PROGRAMS, AND PROJECTS

A project may be managed in three separate scenarios: as a stand-alone project (outside a portfolio or program); within a program; or within a portfolio. Project management has interactions with portfolio and program management when a project is within a portfolio or program. Figure 1-2 shows the relationships between portfolios and programs, between portfolios and projects, and between programs and individual projects. These relationships are not always hierarchical.

Figure 1-2. Example of Portfolio, Program, and Project Management Interfaces

Table 1-2 gives a comparative overview of portfolios, programs, and projects.

Table 1-2. Comparative Overview of Portfolios, Programs, and Projects

1.6 ORGANIZATIONAL PROJECT MANAGEMENT (OPM)

Organizational project management (OPM) is a strategy execution framework utilizing portfolio, program, and project management. It provides a framework that enables organizations to consistently and predictably deliver on organizational strategy, producing better performance; better results; and a sustainable, competitive advantage.

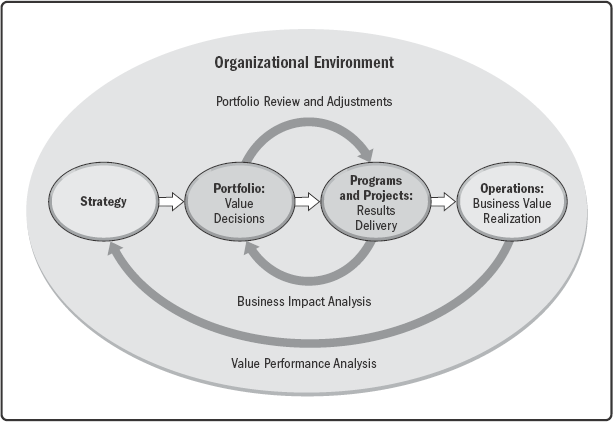

Figure 1-3 shows the organizational environment where strategy, a portfolio, programs and projects, and operations interact.

Figure 1-3. Organizational Project Management

For more information on OPM, refer to The Standard for Organizational Project Management [2].

1.7 PROJECT COMPONENTS AND CONSIDERATIONS

Projects comprise several key components that, when effectively managed, result in their successful completion. This section of the practice guide identifies and explains these components. The various components interrelate to one another during the management of a project.

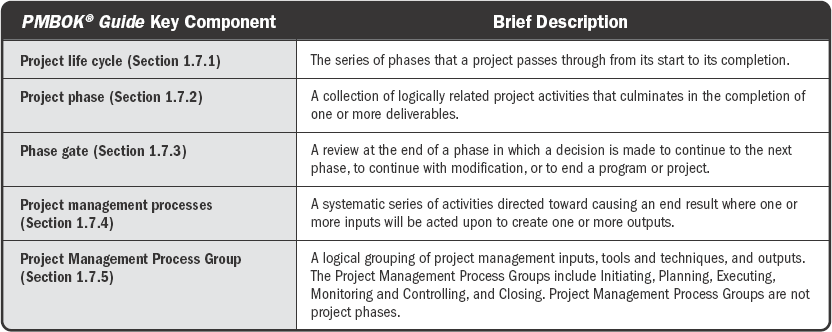

The key components are described briefly in Table 1-3. These components are more fully explained in Sections 1.7.1 through 1.7.5.

Table 1-3. Description of Key Components

1.7.1 PROJECT AND DEVELOPMENT LIFE CYCLES

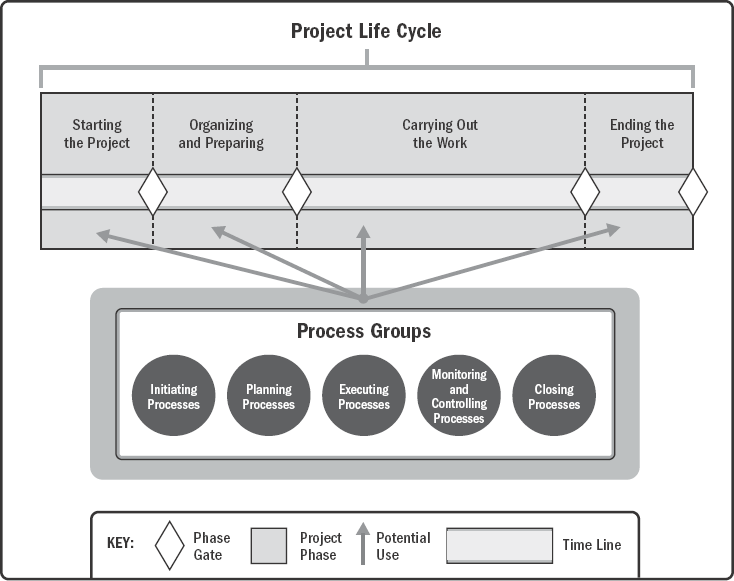

A project life cycle is the series of phases that a project passes through from its start to its completion. It provides the basic framework for managing the project. This basic framework applies regardless of the specific project work involved. The phases may be sequential, iterative, or overlapping. All projects can be mapped to the generic life cycle shown in Figure 1-4.

Figure 1-4. Interrelationship of Key Components in Projects

Project life cycles can be predictive or adaptive. Within a project life cycle, there are generally one or more phases that are associated with the development of the product, service, or result. These are called development life cycles, which can be predictive, adaptive, iterative, incremental, or a hybrid model:

▶In a predictive life cycle, the project scope, time, and cost are determined in the early phases of the life cycle. Any changes to the scope are carefully managed. Predictive life cycles may also be referred to as waterfall life cycles.

▶Adaptive life cycles can be iterative, or incremental. The scope is outlined and agreed before the start of an iteration. Adaptive life cycles are also referred to as agile or change-driven life cycles.

![]() In an iterative life cycle, the project scope is generally determined early in the project life cycle, but time and cost estimates are routinely modified as the project team's understanding of the product increases. Iterations develop the product through a series of repeated cycles, while increments successively add to the functionality of the product.

In an iterative life cycle, the project scope is generally determined early in the project life cycle, but time and cost estimates are routinely modified as the project team's understanding of the product increases. Iterations develop the product through a series of repeated cycles, while increments successively add to the functionality of the product.

![]() In an incremental life cycle, the deliverable is produced through a series of iterations that successively add functionality within a predetermined time frame. The deliverable contains the necessary and sufficient capability to be considered complete only after the final iteration.

In an incremental life cycle, the deliverable is produced through a series of iterations that successively add functionality within a predetermined time frame. The deliverable contains the necessary and sufficient capability to be considered complete only after the final iteration.

▶A hybrid life cycle is a combination of a predictive and an adaptive life cycle. Those elements of the project that are well known or have fixed requirements follow a predictive development life cycle, and those elements that are still evolving follow an adaptive development life cycle.

It is up to the project management team to determine the best life cycle for each project, based on the project's inherent characteristics. The project life cycle needs to be flexible enough to deal with the variety of factors included in the project.

Project life cycles are independent of product life cycles, which may be produced by a project. A product life cycle is the series of phases that represent the evolution of a product, from concept through delivery, growth, maturity, and to retirement.

1.7.2 PROJECT PHASE

A project phase is a collection of logically related project activities that culminates in the completion of one or more deliverables. The phases in a life cycle can be described by a variety of attributes. Attributes may be measurable and unique to a specific phase. Attributes may include but are not limited to:

▶Name (e.g., Phase A, Phase B, Phase 1, Phase 2, proposal phase),

▶Number (e.g., three phases in the project, five phases in the project),

▶Duration (e.g., 1 week, 1 month, 1 quarter),

▶Resource requirements (e.g., people, buildings, equipment),

▶Entrance criteria for a project to move into that phase (e.g., specified approvals documented, specified documents completed), and

▶Exit criteria for a project to complete a phase (e.g., documented approvals, completed documents, completed deliverables).

Projects may be separated into distinct phases or subcomponents. These phases or subcomponents are generally given names that indicate the type of work done in that phase. Examples of phase names include but are not limited to:

▶Concept development,

▶Feasibility study,

▶Customer requirements,

▶Solution development,

▶Design,

▶Prototype,

▶Build,

▶Test,

▶Transition,

▶Commissioning,

▶Milestone review, and

▶Lessons learned.

1.7.3 PHASE GATE

A phase gate (or review) is held at the end of a phase. The project's performance and progress are compared to project and business documents including but not limited to:

▶Project business case,

▶Project charter,

▶Project management plan, and

▶Benefits management plan.

A decision (e.g., go/no-go decision) is made as a result of this comparison to:

▶Continue to the next phase,

▶Continue to the next phase with modification,

▶End the project,

▶Remain in the phase, or

▶Repeat the phase or elements of it.

Depending on the organization, industry, or type of work, phase gates may be referred to by other terms, such as phase review, stage gate, kill point, and phase entrance or phase exit. Organizations may use these reviews to examine other pertinent items which are beyond the scope of this guide, such as product-related documents or models.

1.7.4 PROJECT MANAGEMENT PROCESSES

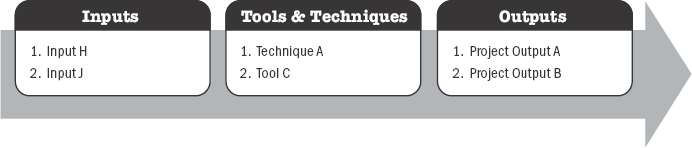

The project life cycle is managed by executing a series of project management activities known as project management processes. There are a total of 49 processes; however, the selection of processes used for any given project depends on the organization and the project—more than likely, all processes will not be used. The outputs can be deliverables or outcomes. Outcomes are the end result of a process. Project management processes apply globally across industries.

Project management processes are logically linked by the outputs they produce. Processes may contain overlapping activities that occur throughout the project. The output of one process generally results in either:

▶An input to another process, or

▶A deliverable of the project or project phase.

Figure 1-5 shows an example of how inputs, tools and techniques, and outputs relate to each other within a process, and with other processes.

Figure 1-5. Example Process: Inputs, Tools & Techniques, and Outputs

The number of process iterations and interactions between processes varies based on the needs of the project. Processes generally fall into one of three categories:

▶Processes used once or at predefined points in the project. The processes Develop Project Charter and Close Project or Phase are examples.

▶Processes that are performed periodically as needed. The process Acquire Resources is performed as resources are needed. The process Conduct Procurements is performed prior to needing the procured item.

▶Processes that are performed continuously throughout the project. The process Define Activities may occur throughout the project life cycle, especially if the project uses rolling wave planning or an adaptive development approach. Many of the Monitoring and Controlling processes are ongoing from the start of the project, until it is closed out.

Project management is accomplished through the appropriate application and integration of logically grouped project management processes. While there are different ways of grouping processes, PMI groups processes into five categories called Process Groups (see Section 1.7.5).

1.7.5 PROJECT MANAGEMENT PROCESS GROUPS

A Project Management Process Group is a logical grouping of project management processes to achieve specific project objectives. Process Groups are independent of project phases. Project management processes are grouped into the following five Project Management Process Groups:

▶Initiating Process Group.. Those processes performed to define a new project or a new phase of an existing project by obtaining authorization to start the project or phase.

▶Planning Process Group.. Those processes required to establish the scope of the project, refine the objectives, and define the course of action required to attain the objectives that the project was undertaken to achieve.

▶Executing Process Group.. Those processes performed to complete the work defined in the project management plan to satisfy the project requirements.

▶Monitoring and Controlling Process Group.. Those processes required to track, review, and regulate the progress and performance of the project; identify any areas in which changes to the plan are required; and initiate the corresponding changes.

▶Closing Process Group.. Those processes performed to formally complete or close the project, phase, or contract.

Process flow diagrams are used throughout this practice guide. The project management processes are linked by specific inputs and outputs where the result or outcome of one process may become the input to another process that is not necessarily in the same Process Group. Note that Process Groups are not the same as project phases.

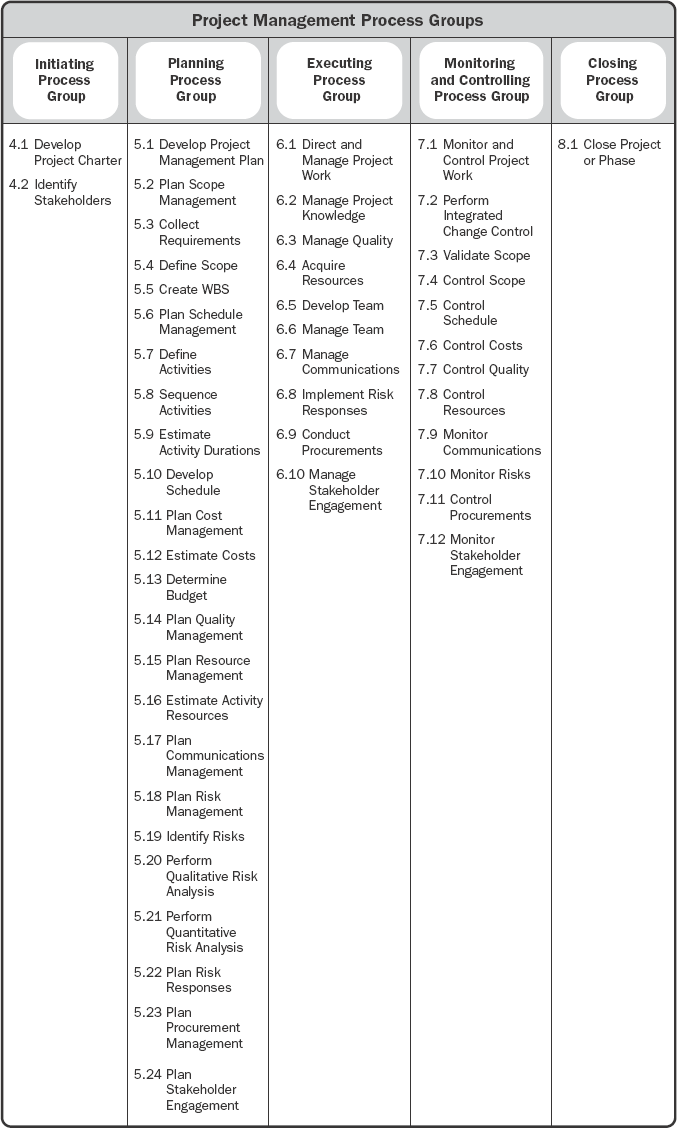

Table 1-4 provides a list of the 49 processes mapped to their respective Process Groups. The numbers refer to the section numbers in this practice guide.

Table 1-4. Process Groups and Project Management Processes

1.8 PROJECT MANAGEMENT DATA AND INFORMATION

Throughout the life cycle of a project, a significant amount of data is collected, analyzed, and transformed. Project data are collected as a result of various processes and are shared within the project team. The collected data are analyzed in context, aggregated, and transformed to become project information during various processes. Information is communicated verbally or stored and distributed in various formats as reports.

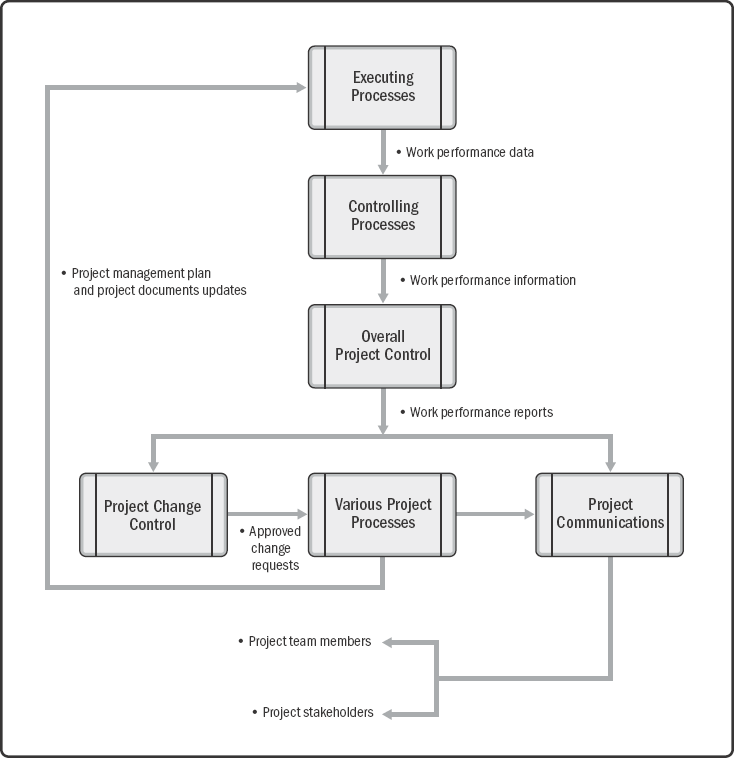

Figure 1-6 shows the flow of project information across the various processes used in managing a project.

Figure 1-6. Project Data, Information, and Report Flow

1.9 TAILORING

Usually, project managers apply a project management methodology to their work. A methodology is a system of practices, techniques, procedures, and rules used by those who work in a discipline. Specific methodology recommendations are outside the scope of this practice guide.

Project management methodologies may be:

▶Developed by experts within the organization,

▶Purchased from vendors,

▶Obtained from professional associations, or

▶Acquired from government agencies.

Tailoring is the deliberate adaptation of approach, governance, and processes to make them more suitable for the given environment and the task(s) at hand.

In a project environment, tailoring includes considering the approaches, processes, interim deliverables, and choice of people to engage with. The tailoring process is driven by a mindset and set of values that influence the tailoring decisions. The project manager collaborates with the project team, sponsor, organizational management, or combination thereof, in the tailoring. In some cases, an organization may require that specific project management methodologies be used.

Tailoring is necessary because each project is unique. Not every process, tool, technique, input, or output identified in this practice guide is required on every project. Tailoring should address the competing constraints of scope, schedule, cost, resources, quality, and risk. The importance of each constraint is different for each project, and the project manager tailors the approach to manage these constraints based on the project environment, organizational culture, stakeholder needs, and other variables.

Sound project management methodologies take into account the unique nature of projects and allow tailoring, to some extent, by the project manager.

Tailoring produces direct and indirect benefits to organizations. These include, but are not limited to:

▶More commitment from project team members who helped to tailor the approach,

▶Customer-oriented focus, as the needs of the customer are an important influencing factor in its development, and

▶More efficient use of project resources.

In tailoring project management, the project manager should also consider the varying levels of governance that may be required and within which the project will operate, as well as considering the culture of the organization (see Section 2.3). In addition, consideration of whether the customer of the project is internal or external to the organization may affect project management tailoring decisions.

The PMBOK Guide® – Seventh Edition outlines a four-step tailoring process:

▶Step 1: Select Initial Development Approach.—This step determines the development approach that will be used for the project. Project teams apply their knowledge of the product, delivery cadence, and awareness of the available options to select the most appropriate development approach for the situation.

▶Step 2: Tailor for the Organization.—While project teams own and improve their processes, organizations often require some level of approval and oversight. Many organizations have a project methodology, general management approach, or general development approach that is used as a starting point for their projects. Organizations that have established process governance need to ensure tailoring is aligned to policy. To demonstrate that the project team's tailoring decisions do not threaten the organization's larger strategic or stewardship goals, project teams may need to justify using a tailored approach.

▶Step 3: Tailor for the Project.—Many attributes influence tailoring for the project. These include, but are not limited to, product/deliverable, project team, and culture. The project team should ask questions about each attribute to help guide them in the tailoring process. Answers to these questions can help identify the need to tailor processes, delivery approach, life cycle, tools, methods, and artifacts.

▶Step 4: Implement Ongoing Improvement.—The process of tailoring is not a single, one-time exercise. During progressive elaboration, issues with how the project team is working, how the product or deliverable is evolving, and other learnings will indicate where further tailoring could bring improvements. Review points, phase gates, and retrospectives all provide opportunities to inspect and adapt the process, development approach, and delivery frequency as necessary.

1.10 BENEFITS MANAGEMENT AND BUSINESS DOCUMENTS

Projects are initiated to realize opportunities that are aligned with an organization's strategic goals. Prior to initiating a project, a business case is often developed to outline the project objectives, the required investment, and financial and qualitative criteria for project success. The business case provides the basis to measure success and progress throughout the project life cycle by comparing the results with the objectives and the identified success criteria. The business case may be used before project initiation and may result in a go/no-go decision for the project.

A needs assessment often precedes the business case. The needs assessment involves understanding business goals and objectives, issues, and opportunities and recommending proposals to address them. The results of the needs assessment may be summarized in the business case document.

Projects are typically initiated as a result of one or more of the following strategic considerations:

▶Market demand,

▶Strategic opportunity/business need,

▶Social need,

▶Environmental consideration,

▶Customer request,

▶Technological advancement,

▶Legal or regulatory requirement, and

▶Existing or forecasted problem.

A benefits management plan describes how and when the benefits of the project will be delivered and how they will be measured. The benefits management plan may include the following:

▶Target benefits. The expected tangible and intangible business value to be gained by the implementation of the product, service, or result.

▶Strategic alignment. How the project benefits support and align with the business strategies of the organization.

▶Time frame for realizing benefits. Benefits by phase: short term, long term, and ongoing.

▶Benefits owner. The accountable person or group that monitors, records, and reports realized benefits throughout the time frame established in the plan.

▶Metrics. The direct and indirect measurements used to show the benefits realized.

▶Risks. Risks associated with achieving target benefits.

The success of the project is measured against the project objectives and success criteria. In many cases, the success of the product, service, or result is not known until sometime after the project is complete. For example, an increase in market share, a decrease in operating expenses, or the success of a new product may not be known when the project is transitioned to operations. In these circumstances, the project management office (PMO), portfolio steering committee, or some other business function within the organization should evaluate the success at a later date to determine if the outcomes met the business objectives.

Development and maintenance of the project benefits management plan is an iterative activity. This document complements the business case, project charter, and project management plan. The project manager works with the sponsor to ensure that the project charter, project management plan, and the benefits management plan remain in alignment throughout the life cycle of the project. See Business Analysis for Practitioners: A Practice Guide [3], The Standard for Program Management [4], and The Standard for Portfolio Management [5].

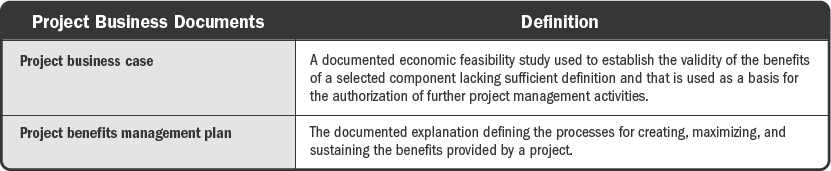

A project manager needs to ensure that the project management approach captures the intent of business documents. These documents are defined in Table 1-5. These two documents are interdependent and iteratively developed and maintained throughout the life cycle of the project.

The project sponsor is generally accountable for the development and maintenance of the project business case document. The project manager is responsible for providing recommendations and oversight to keep the project business case, project management plan, project charter, and project benefits management plan success measures in alignment with one another and with the goals and objectives of the organization.

Both the business case and the benefits management plan are developed prior to the project being initiated. Additionally, both documents are referenced after the project has been completed. Therefore, they are considered business documents rather than project documents or components of the project management plan. As appropriate, these business documents may be inputs to some of the processes involved in managing the project, such as developing the project charter.

Table 1-5. Project Business Documents

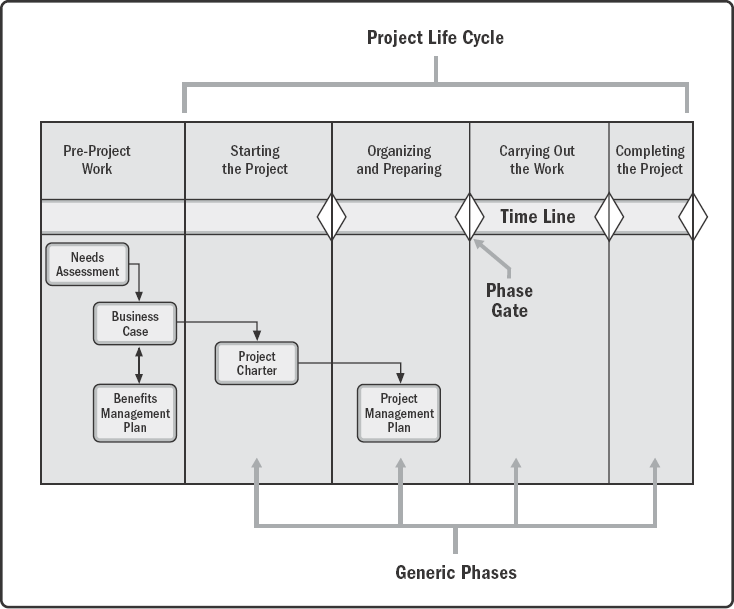

Project managers tailor the noted project management documents for their projects. In some organizations, the business case and benefits management plan are maintained at the program level. Project managers then work with the appropriate program managers to ensure the project management documents are aligned with the program documents. Figure 1-7 illustrates the interrelationship of these critical project management business documents and the needs assessment. Figure 1-7 shows an approximation of the life cycle of these various documents against the project life cycle.

Figure 1-7. Interrelationship of Needs Assessment and Critical Business/Project Documents

1.11 PROJECT CHARTER, PROJECT MANAGEMENT PLAN, AND PROJECT DOCUMENTS

The project charter is defined as a document issued by the project sponsor that formally authorizes the existence of a project and provides the project manager with the authority to apply organizational resources to project activities.

The project management plan is defined as the document that describes how the project will be executed, monitored, and controlled. It integrates and consolidates all of the subsidiary management plans and baselines, and other information that is essential for managing the project. The individual aspects of the project determine which components of the project management plan are needed.

Project management plan components include but are not limited to:

▶Subsidiary management plans:.

![]() Scope management plan. Establishes how the scope will be defined, developed, monitored, controlled, and validated.

Scope management plan. Establishes how the scope will be defined, developed, monitored, controlled, and validated.

![]() Requirements management plan. Establishes how the requirements will be analyzed, documented, and managed.

Requirements management plan. Establishes how the requirements will be analyzed, documented, and managed.

![]() Schedule management plan. Establishes the criteria and the activities for developing, monitoring, and controlling the schedule.

Schedule management plan. Establishes the criteria and the activities for developing, monitoring, and controlling the schedule.

![]() Cost management plan. Establishes how the costs will be planned, structured, and controlled.

Cost management plan. Establishes how the costs will be planned, structured, and controlled.

![]() Quality management plan. Establishes how an organization´s quality policies, methodologies, and standards will be implemented in the project.

Quality management plan. Establishes how an organization´s quality policies, methodologies, and standards will be implemented in the project.

![]() Resource management plan. Provides guidance on how project resources should be categorized, allocated, managed, and released.

Resource management plan. Provides guidance on how project resources should be categorized, allocated, managed, and released.

![]() Communications management plan. Establishes how, when, and by whom information about the project will be administered and disseminated.

Communications management plan. Establishes how, when, and by whom information about the project will be administered and disseminated.

![]() Risk management plan. Establishes how the risk activities will be structured and performed.

Risk management plan. Establishes how the risk activities will be structured and performed.

![]() Procurement management plan. Establishes how the project team will acquire goods and services from outside of the performing organization.

Procurement management plan. Establishes how the project team will acquire goods and services from outside of the performing organization.

![]() Stakeholder engagement plan. Establishes how stakeholders will be engaged in project decisions and execution, according to their needs, interests, and impact.

Stakeholder engagement plan. Establishes how stakeholders will be engaged in project decisions and execution, according to their needs, interests, and impact.

▶Baselines:.

![]() Scope baseline. The approved version of a scope statement, work breakdown structure (WBS), and its associated WBS dictionary, which can be changed using formal change control procedures and is used as a basis for comparison.

Scope baseline. The approved version of a scope statement, work breakdown structure (WBS), and its associated WBS dictionary, which can be changed using formal change control procedures and is used as a basis for comparison.

![]() Schedule baseline. The approved version of a schedule model that can be changed using formal change control procedures and is used as a basis for comparison to the actual results.

Schedule baseline. The approved version of a schedule model that can be changed using formal change control procedures and is used as a basis for comparison to the actual results.

![]() Cost baseline. The approved version of the time-phased project budget, excluding any management reserves, which can be changed using formal change control procedures and is used as a basis for comparison to the actual results.

Cost baseline. The approved version of the time-phased project budget, excluding any management reserves, which can be changed using formal change control procedures and is used as a basis for comparison to the actual results.

▶Additional components. Most components of the project management plan are produced as outputs from other processes, though some are produced during this process. Those components developed as part of this process will be dependent on the project; however, they often include but are not limited to:

![]() Change management plan. Describes how the change requests throughout the project will be formally authorized and incorporated.

Change management plan. Describes how the change requests throughout the project will be formally authorized and incorporated.

![]() Configuration management plan. Describes how the information about the items of the project (and which items) will be recorded and updated so that the product, service, or result of the project remains consistent and/or operative.

Configuration management plan. Describes how the information about the items of the project (and which items) will be recorded and updated so that the product, service, or result of the project remains consistent and/or operative.

![]() Performance measurement baseline. An integrated scope-schedule-cost plan for the project work against which project execution is compared to measure and manage performance.

Performance measurement baseline. An integrated scope-schedule-cost plan for the project work against which project execution is compared to measure and manage performance.

![]() Project life cycle. Describes the series of phases that a project passes through from its initiation to its closure.

Project life cycle. Describes the series of phases that a project passes through from its initiation to its closure.

![]() Development approach. Describes the product, service, or result development approach, such as predictive, iterative, agile, or a hybrid model.

Development approach. Describes the product, service, or result development approach, such as predictive, iterative, agile, or a hybrid model.

![]() Management reviews. Identifies the points in the project when the project manager and relevant stakeholders will review the project progress to determine if performance is as expected, or if preventive or corrective actions are necessary.

Management reviews. Identifies the points in the project when the project manager and relevant stakeholders will review the project progress to determine if performance is as expected, or if preventive or corrective actions are necessary.

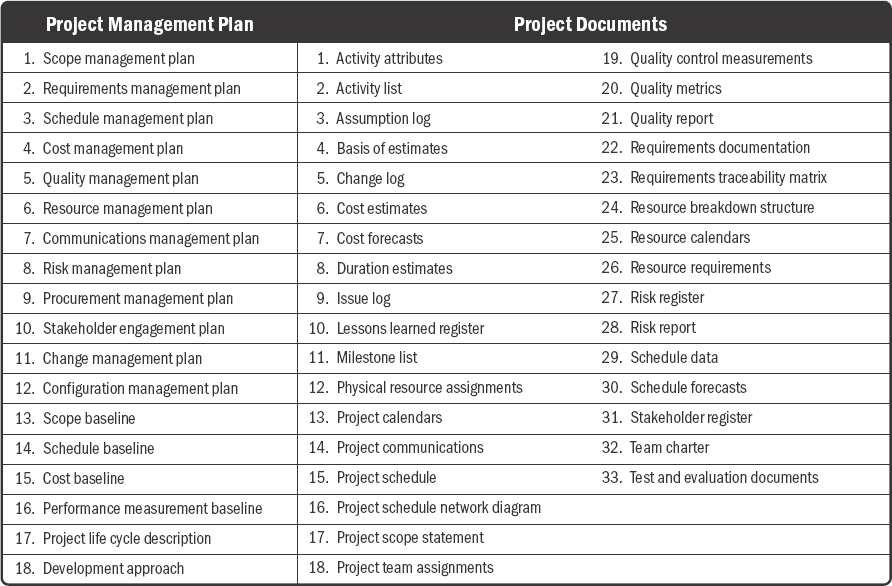

While the project management plan is one of the primary documents used to manage the project, other project documents are also used. These other documents are not part of the project management plan; however, they are necessary to manage the project effectively. Table 1-6 is a representative list of the project management plan components and project documents.

Table 1-6. Project Management Plan and Project Documents

1.12 PROJECT SUCCESS MEASURES

One of the most common challenges in project management is determining whether or not a project is successful.

Traditionally, the project management metrics of time, cost, scope, and quality have been the most important factors in defining the success of a project. More recently, practitioners and scholars have determined that project success should also be measured with consideration toward achievement of the project objectives.

Project stakeholders may have different ideas as to what the successful completion of a project will look like and which factors are the most important. It is critical to clearly document the project objectives and to select objectives that are measurable. Three questions that the key stakeholders and the project manager should answer are:

▶What does success look like for this project?

▶How will success be measured?

▶What factors may impact success?

The answer to these questions should be documented and agreed upon by the key stakeholders and the project manager.

Project success may include additional criteria linked to the organizational strategy and to the delivery of business results. These project objectives may include but are not limited to:

▶Completing the project benefits management plan;

▶Meeting the agreed-upon financial measures documented in the business case. These financial measures may include but are not limited to:

![]() Net present value (NPV),

Net present value (NPV),

![]() Return on investment (ROI),

Return on investment (ROI),

![]() Internal rate of return (IRR),

Internal rate of return (IRR),

![]() Payback period (PBP), and

Payback period (PBP), and

![]() Benefit-cost ratio (BCR).

Benefit-cost ratio (BCR).

▶Meeting business case nonfinancial objectives;

▶Completing movement of an organization from its current state to the desired future state;

▶Fulfilling contract terms and conditions;

▶Meeting organizational strategy, goals, and objectives;

▶Achieving stakeholder satisfaction;

▶Acceptable customer/end-user adoption;

▶Integration of deliverables into the organization's operating environment;

▶Achieving agreed-upon quality of delivery;

▶Meeting governance criteria; and

▶Achieving other agreed-upon success measures or criteria (e.g., process throughput).

The project team needs to be able to assess the project situation, balance the demands, and maintain proactive communication with stakeholders in order to deliver a successful project.

When the business alignment for a project is constant, the chance for project success greatly increases because the project remains aligned with the strategic direction of the organization.

It is possible for a project to be successful from a scope/schedule/budget viewpoint, and to be unsuccessful from a business viewpoint. This can occur when there is a change in the business needs or the market environment before the project is completed.