With all of these different ways to start programs on different platforms, it can be difficult to remember what tools to use in a given situation. Moreover, some of these tools are called in ways that are complicated and thus easy to forget (for me, at least). I write scripts that need to launch Python programs often enough that I eventually wrote a module to try to hide most of the underlying details. While I was at it, I made this module smart enough to automatically pick a launch scheme based on the underlying platform. Laziness is the mother of many a useful module.

Example 5-25 collects

in a single module many of the techniques we’ve met in this chapter.

It implements an abstract superclass, LaunchMode, which defines what it means to

start a Python program, but it doesn’t define how. Instead, its

subclasses provide a run method

that actually starts a Python program according to a given scheme, and

(optionally) define an announce

method to display a program’s name at startup time.

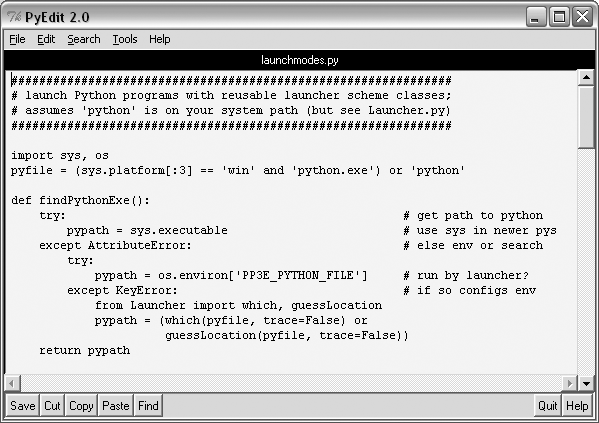

Example 5-25. PP3Elaunchmodes.py

###############################################################

# launch Python programs with reusable launcher scheme classes;

# assumes 'python' is on your system path (but see Launcher.py)

###############################################################

import sys, os

pyfile = (sys.platform[:3] == 'win' and 'python.exe') or 'python'

def findPythonExe( ):

try: # get path to python

pypath = sys.executable # use sys in newer pys

except AttributeError: # else env or search

try:

pypath = os.environ['PP3E_PYTHON_FILE'] # run by launcher?

except KeyError: # if so configs env

from Launcher import which, guessLocation

pypath = (which(pyfile, trace=False) or

guessLocation(pyfile, trace=False))

return pypath

class LaunchMode:

def _ _init_ _(self, label, command):

self.what = label

self.where = command

def _ _call_ _(self): # on call, ex: button press callback

self.announce(self.what)

self.run(self.where) # subclasses must define run( )

def announce(self, text): # subclasses may redefine announce( )

print text # methods instead of if/elif logic

def run(self, cmdline):

assert 0, 'run must be defined'

class System(LaunchMode): # run shell commands

def run(self, cmdline): # caveat: blocks caller

pypath = findPythonExe( )

os.system('%s %s' % (pypath, cmdline)) # unless '&' added on Linux

class Popen(LaunchMode): # caveat: blocks caller

def run(self, cmdline): # since pipe closed too soon

pypath = findPythonExe( )

os.popen(pypath + ' ' + cmdline)

class Fork(LaunchMode):

def run(self, cmdline):

assert hasattr(os, 'fork') # for Unix systems today

cmdline = cmdline.split( ) # convert string to list

if os.fork( ) == 0: # start new child process

pypath = findPythonExe( )

os.execvp(pypath, [pyfile] + cmdline) # run new program in child

class Start(LaunchMode):

def run(self, cmdline): # for Windows only

assert sys.platform[:3] == 'win' # runs independent of caller

os.startfile(cmdline) # uses Windows associations

class StartArgs(LaunchMode):

def run(self, cmdline): # for Windows only

assert sys.platform[:3] == 'win' # args may require real start

os.system('start ' + cmdline) # creates pop-up window

class Spawn(LaunchMode): # for Windows or Unix

def run(self, cmdline): # run python in new process

pypath = findPythonExe( ) # runs independent of caller

os.spawnv(os.P_DETACH, pypath, (pyfile, cmdline)) # P_NOWAIT: dos box

class Top_level(LaunchMode):

def run(self, cmdline): # new window, same process

assert 0, 'Sorry - mode not yet implemented' # tbd: need GUI class info

if sys.platform[:3] == 'win':

PortableLauncher = Spawn # pick best launcher for platform

else: # need to tweak this code elsewhere

PortableLauncher = Fork

class QuietPortableLauncher(PortableLauncher):

def announce(self, text):

pass

def selftest( ):

myfile = 'launchmodes.py'

program = 'Gui/TextEditor/textEditor.py ' + myfile # assume in cwd

raw_input('default mode...')

launcher = PortableLauncher('PyEdit', program)

launcher( ) # no block

raw_input('system mode...')

System('PyEdit', program)( ) # blocks

raw_input('popen mode...')

Popen('PyEdit', program)( ) # blocks

if sys.platform[:3] == 'win':

raw_input('DOS start mode...') # no block

StartArgs('PyEdit', os.path.normpath(program))( )

if _ _name_ _ == '_ _main_ _': selftest( )Near the end of the file, the module picks a default class based

on the sys.platform attribute:

PortableLauncher is set to a class

that uses spawnv on Windows and one

that uses the fork/exec combination elsewhere (in recent

Pythons, we could probably just use the spawnv scheme on most platforms, but the

alternatives in this module are used in additional contexts). If you

import this module and always use its PortableLauncher attribute, you can forget

many of the platform-specific details enumerated in this

chapter.

To run a Python program, simply import the PortableLauncher class, make an instance by

passing a label and command line (without a leading “python” word),

and then call the instance object as though it were a function. The

program is started by a call operation instead of a method so that the

classes in this module can be used to generate callback handlers in

Tkinter-based GUIs. As we’ll see in the upcoming chapters,

button-presses in Tkinter invoke a callable object with no arguments;

by registering a PortableLauncher

instance to handle the press event, we can automatically start a new

program from another program’s GUI.

When run standalone, this module’s selftest function is invoked as usual. On

both Windows and Linux, all classes tested start a new Python text

editor program (the upcoming PyEdit GUI program again) running

independently with its own window. Figure 5-2 shows one in action on

Windows; all spawned editors open the

launchmodes.py source file automatically, because

its name is passed to PyEdit as a command-line argument. As coded,

both System and Popen block the caller until the editor

exits, but PortableLauncher

(really, Spawn or Fork) and Start do not:[*]

C:...PP3E>python launchmodes.py

default mode...

PyEdit

system mode...

PyEdit

popen mode...

PyEdit

DOS start mode...

PyEditAs a more practical application, this file is also used by

launcher scripts designed to run examples in this book in a portable

fashion. The PyDemos and PyGadgets scripts at the top of this book’s

examples distribution directory tree (described in the Preface) simply

import PortableLauncher and

register instances to respond to GUI events. Because of that, these

two launcher GUIs run on both Windows and Linux unchanged (Tkinter’s

portability helps too, of course). The PyGadgets script even

customizes PortableLauncher to

update a label in a GUI at start time.

class Launcher(launchmodes.PortableLauncher): # use wrapped launcher class

def announce(self, text): # customize to set GUI label

Info.config(text=text)We’ll explore these scripts in Part III (but feel free to peek at

the end of Chapter 10 now).

Because of this role, the Spawn

class in this file uses additional tools to search for the Python

executable’s path, which is required by os.spawnv. If the sys.executable path string is not available

in an older version of Python that you happen to be using, it calls

two functions exported by a file named

Launcher.py to find a suitable Python executable

regardless of whether the user has added its directory to his system

PATH variable’s setting. The idea

is to start Python programs, even if Python hasn’t been installed in

the shell variables on the local machine. Because we’re going to meet

Launcher.py in the next chapter, though, I’m

going to postpone further details for now.

[*] This is fairly subtle. Technically, Popen blocks its caller only because the

input pipe to the spawned program is closed too early, when the

os.popen call’s result is

garbage collected in Popen.run;

os.popen normally does not

block (in fact, assigning its result here to a global variable

postpones blocking, but only until the next Popen object run frees the prior

result). On Linux, adding an & to the end of the constructed

command line in the System and

Popen.run methods makes these

objects no longer block their callers when run. Since the fork/exec, spawnv, and system/start schemes seem at least as good in

practice, these Popen block

states have not been addressed. Note too that the StartArgs scheme may not generate a DOS

console pop-up window in the self-test if the text editor program

file’s name ends in a .pyw extension;

starting .py program files normally creates

the console pop-up box.