If you examine the brief history of software engineering just outlined, you'll notice a pattern: every new methodology and technology incorporates the benefits of its preceding technology and improves on the deficiencies of the preceding technology. However, every new generation also introduces new challenges. Therefore, I say that modern software engineering is the ongoing refinement of the ever-increasing degrees of decoupling.

Put differently, coupling is bad, but coupling is unavoidable. An absolutely decoupled application would be useless, because it would add no value. Developers can only add value by coupling things together. Indeed, the very act of writing code is coupling one thing to another. The real question is how to wisely choose what to be coupled to. I believe there are two types of coupling, good and bad. Good coupling is business-level coupling. Developers add value by implementing a system use case or a feature, by coupling software functionality together. Bad coupling is anything to do with writing plumbing. What was wrong with .NET and COM was not the concept; it was the fact that developers could not rely on off-the-shelf plumbing and still had to write so much of it themselves. The real solution is not just off-the-shelf plumbing, but rather standard off-the-shelf plumbing. If the plumbing is standard, the boundary problem goes away, and applications can utilize ready-made plumbing. However, all technologies (.NET, Java, etc.) use the client thread to jump into the object. How can you possibly take a .NET thread and give it to a Java object? The solution is to avoid call-stack invocation and instead to use message exchange. The technology vendors can standardize the format of the message and agree on ways to represent transactions, security credentials, and so on. When the message is received by the other side, the implementation of the plumbing there will convert the message to a native call (on a .NET or a Java thread) and proceed to call the object. Consequently, any attempt to standardize the plumbing has to be message-based.

And so, recognizing the problems of the past, in the late 2000s the service-oriented methodology has emerged as the answer to the shortcomings of component-orientation. In a service-oriented application, developers focus on writing business logic and expose that logic via interchangeable, interoperable service endpoints. Clients consume those endpoints (not the service code, or its packaging). The interaction between the clients and the service endpoint is based on a standard message exchange, and the service publishes some standard metadata describing what exactly it can do and how clients should invoke operations on it. The metadata is the service equivalent of the C++ header file, the COM type library, or the .NET assembly metadata, yet it contains not just operation metadata (such as methods and parameters) but also plumbing metadata. Incompatible clients—that is, clients that are incompatible with the plumbing expectations of the object—cannot call it, since the call will be denied by the platform. This is an extension of the object- and component-oriented compile-time notion that a client that is incompatible with an object's metadata cannot call it. Demanding compatibility with the plumbing (on top of the operations) is paramount. Otherwise, the object must always check on every call that the client meets its expectations in terms of security, transactions, reliability and so on, and thus the object invariably ends up infused with plumbing. Not only that, but the service's endpoint is reusable by any client compatible with its interaction constraints (such as synchronous, transacted, and secure communication), regardless of the client's implementation technology.

In many respects, a service is the natural evolution of the component, just as the component was the natural evolution of the object, which was the natural evolution of the function. Service-orientation is, to the best of our knowledge as an industry, the correct way to build maintainable, robust, and secure applications.

The result of improving on the deficiencies of component-orientation (i.e., classic .NET) is that when developing a service-oriented application, you decouple the service code from the technology and platform used by the client from many of the concurrency management issues, from transaction propagation and management, and from communication reliability, protocols, and patterns. By and large, securing the transfer of the message itself from the client to the service is also outside the scope of the service, and so is authenticating the caller. The service may still do its own local authorization, however, if the requirements so dictate. Similarly, as long as the endpoint supports the contract the client expects, the client does not care about the version of the service. There are also tolerances built into the standards to deal with versioning tolerance of the data passed between the client and the service.

Service-orientation yields maintainable applications because the applications are decoupled on the correct aspects. As the plumbing evolves, the application remains unaffected. A service-oriented application is robust because the developers can use available, proven, and tested plumbing, and the developers are more productive because they get to spend more of the cycle time on the features rather than the plumbing. This is the true value proposition of service-orientation: enabling developers to extract the plumbing from their code and invest more in the business logic and the required features.

The many other hailed benefits, such as cross-technology interoperability, are merely a manifestation of the core benefit. You can certainly interoperate without resorting to services, as was the practice until service-orientation. The difference is that with ready-made plumbing you rely on the plumbing to provide the interoperability for you.

When you write a service, you usually do not care which platform the client executes on—that is immaterial, which is the whole point of seamless interoperability. However, a service-oriented application caters to much more than interoperability. It enables developers to cross boundaries. One type of boundary is the technology and platform, and crossing that boundary is what interoperability is all about. But other boundaries may exist between the client and the service, such as security and trust boundaries, geographical boundaries, organizational boundaries, timeline boundaries, transaction boundaries, and even business model boundaries. Seamlessly crossing each of these boundaries is possible because of the standard message-based interaction. For example, there are standards for how to secure messages and establish a secure interaction between the client and the service, even though both may reside in domains (or sites) that have no direct trust relationship. There is also a standard that enables the transaction manager on the client side to flow the transaction to the transaction manager on the service side, and have the service participate in that transaction, even though the two transaction managers never enlist in each other's transactions directly.

I believe that every application should be service-oriented, not just Enterprise applications that require interoperability and scalability. Writing plumbing in any type of application is wrong, constituting a waste of your time, effort, and budget, resulting in degradation of quality. Just as with .NET every application was component-oriented (which was not so easy to do with COM alone) and with C++ every application was object-oriented (which was not so easy to do with C alone), when using WCF, every application should be service-oriented.

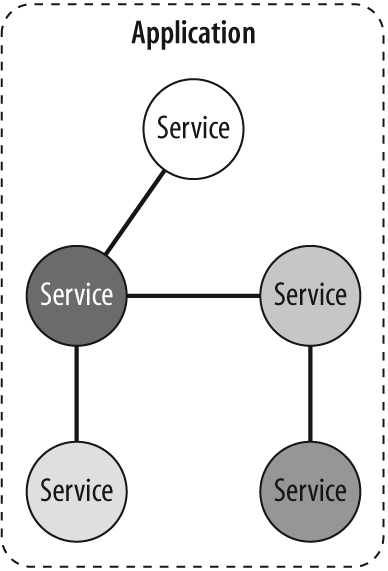

A service is a unit of functionality exposed to the world over standard plumbing. A service-oriented application is simply the aggregation of services into a single logical, cohesive application (see Figure A-1), much as an object-oriented application is the aggregation of objects.

The application itself may expose the aggregate as a new service, just as an object can be composed of smaller objects.

Inside services, developers still use concepts such as specific programming languages, versions, technologies and frameworks, operating systems, APIs, and so on. However, between services you have the standard messages and protocols, contracts, and metadata exchange.

The various services in an application can be all in the same location or be distributed across an intranet or the Internet, and they may come from multiple vendors and be developed across a range of platforms and technologies, versioned independently, and even execute on different timelines. All of those plumbing aspects are hidden from the clients in the application interacting with the services. The clients send the standard messages to the services, and the plumbing at both ends marshals away the differences between the clients and the services by converting the messages to and from the neutral wire representation.