Impact of Bailouts on the Economy of a Sovereign

Theoretically, the conditions attached to the second Greek bailout were wide-ranging privatizations and deep cuts in government expenditures. Such predictions were precarious because they failed to account for the ongoing reaction of the population against austerity measures.

Let’s face it. Neither the EU, nor the ECB, let alone the IMF, had a roadmap for Greece (or for Italy, Spain, Portugal, and France). On paper, much of what came out of the marathon sessions at EU headquarters, in Brussels, might have made sense, but there existed notable risks in implementation reflected in widespread concern among economists and analysts.

While the second package seemed to be more realistic than the first (launched in April 2010) it still contained unrealistic hypotheses. The implementation of tougher austerity measures and other requirements was hanging on the government’s resolve and popular support for the measures. But by large majority the Greek public doubted any money will filter down to common citizen, as most was supposed to be in a blocked account earmarked for paying past obligations. New debt accumulated to pay down old debt.

Keywords

Impact of bailouts; funding gap; Euroland and Greece; state politics; sovereign debt; restructuring; expected results; monkey money; credit default swaps

5.1 Bailout Fatigue

To describe the array of ultra-leftist and ultra-traditionalist forces bent on blocking reform Alexis Papahelas, editor of Kathimerini, easily Greece’s best newspaper, has coined the term “coalition of the unwilling.” He also noted that the number of citizens suspicious of all change may increase, as middle-class Greeks see their hard-earned prosperity go up in smoke.1

That’s Euroland of the bailouts but is the alternative any better? By all likelihood, if Greece were to break with Euroland and launch a new drachma, local banks would be besieged by panicked depositors. “…The shops will empty and some people will jump out of windows,” Theodoros Pangalos, deputy prime minister, told the Spanish daily El Mundo.2

Pangalos impressed some of his compatriots (and annoyed others) by saying that common citizens in Greece, as well as the political elite, wasted loans and subsidies and brought the country to the edge of chaos. His explanation of the debt crisis has been: “We ate it up together,” and in this he is right. The bill came due and the Greek Treasury did not have the reserves to pay it.

Instead, in April 2010 Euroland and the IMF offered a bailout but by mid-2011, when the statements by Papahelas and Pangalos were made, it had proved to be insufficient (if not outright inefficient). A few months later, on February 21, 2012, Euroland’s finance ministers sealed a second bailout for Greece, to the tune of euro 130 billion ($170 billion) in new financing.

Theoretically, the Eurogroup (finance minister 17 nations that use the euro) gave Greece the funding it needed to avoid a potential default. This was a marathon session and Olli Rehn, vice president of the European Commission, said that the previous night he learned that marathon is indeed a Greek word.3 Practically, however, the die was far from being cast.

Rehn pressed the point that the Greek economy cannot rely anymore on a large public administration financed by cheap debt, but rather needs to lean on investment—both Greek and foreign. According to Rehn, another goal Greece has to honor for the second rescue is to reduce to 120 percent, by 2020, the ratio of public debt to GDP. (This stood at 160 percent at time of first bailout.) Instead, 10 months later, as 2012 came to a close:

• The Greek debt-to-GDP ratio stood at an unhealthy 179.8 percent, and

• Nobody can really answer the question how it happens that rather than going down with the PSI, it has gone up.

Bailout fatigue starts being felt when objectives are not met and hopes evaporate, but it is not easy to say “to hell with it” because of the funding gap which will leave the Greek Treasury empty of money for the essentials. Economists calculate that until 2016 (three years away) this funding gap will stand at about euro 43 billion, while they don’t see that (under current conditions) Greece will be able to restart financing in the capital markets till 2015–2016 even for modest amounts.

Moreover, interest costs will be higher due to a greater usage of short-term treasury bills while, because the PSI wounded Greek banks, bank recapitalization is pressing (some analysts believe that eventually this would require about euro 50 billion, instead of the much lower figure I gave in Chapter 4). With all this in mind Table 5.1 presents the major chapters of the current Greek sovereign debt toward the EU (really the EFSF), European Central Bank, and IMF.

Table 5.1

Greek Public Debt Toward the “Untouchables”: EU, ECB, IMF

| Euro | |

| Bailout I | 110 billion |

| Bailout II | 130 billion |

| Bailouts I+II (some of this money is still to be paid) | 240 billion |

| ECB is owed by Greece (because of bonds used as collateral with SMP (Chapter 4)) | 40 billion |

| In TARGET2a Bank of Greece owes | 106 billion |

| Total current exposure in public debt | 386 billion |

aTARGET2 is ECB’s payment system, and member states are supposed to pay their accounts.

Prior to Bailout I and of the PSI haircut Greek public debt stood at the euro 350 billion level ($455 billion). Some Bailout I money was used to repay ECB. Other has been employed to confront demand for cash to pay for maturities (interest and capital). PSI has saved euro 158.76 billion4; but at the other side of the balance sheet there has been the guarantee by Athens for new sovereign bonds and Greek bank recapitalization.

Some economists argue that the TARGET II imbalance (which is a Bank of Greece liability) should not be added to this account, because it is relevant only if Greece leaves the euro. While this remains a possibility (Chapter 6) even if Greece stays in euro, the negative balance of euro 106 billion in TARGET2 is due. As far as clearing accounts are concerned there should be only a small and temporary payments balance which is sometimes positive and sometimes negative.

All accounts made, however, with “pluses” and “minuses” rapidly changing (hence difficult to track), the fact remains that even without the huge TARGET2 negative balance as 2012 came to a close the Greek debt-to-GDP ratio stood at nearly 180 percent and was projected to reach 190 percent in 2013. This is a significant increase over 160 percent when Bailout I started—despite the debt reduction brought by PSI.

Evidently there exist hypotheses about why this is so, and one of them is that the assumptions which were made about the positive effects of Euroland’s rescues were wrong. The second bailout was supposed to give Greece enough space to improve its competitiveness. At least that’s what Christine Lagarde, IMF’s CEO said. But is it really documented by facts?

Theoretically, the conditions attached to the second Greek bailout were to be executed by the next government, to emerge from the April 2012 elections. Practically, this was not at all sure because in February 2012 nobody could tell what kind of government will come out of elections two months later. Predictions were precarious, given:

• The ongoing reaction of the population against austerity measures, and

• The possibility left parties might gain a majority of sorts in the new parliament, form a government and call for renegotiation of all conditions.

On paper, most of what came out of the marathon 13-hour session at EU headquarters, in Brussels, might have made sense, but there existed notable risks in its implementation reflected in widespread concern among economists and analysts. Details which started to be released brought these risks in perspective. While the second package seemed to be more realistic than the first (launched in April 2010) it still contained unrealistic hypotheses.

The implementation of tougher austerity measures and other requirements was hanging on the new government’s resolve and popular support for the measures. But by large majority the Greek public doubted any money will filter down to common citizen, as most was supposed to be in a blocked account earmarked for paying past obligations. New debt is accumulating to pay down old debt.

For instance, more than half of the payments scheduled for late March 2012 were supposed to go to the ECB to cover a maturing position. This was partly a reflection of the fact that the Greek public debt has been staggering. Exposure to Greek bonds by the ECB consumed the lion’s share of its reserves. (Over and above that came ECB’s exposure to Portugal, Ireland, Spain, Italy, and so on.)

The common citizen’s worries and uncertainty about the future contrasted to the optimistic scenario at EU headquarters which assumed that even if eventually Greece exits the euro this will happen only after policymakers have erected a credible firewall. Furthermore, in real life the hypothesis that Spain, Italy, and other member states will not be greatly affected by the economic earthquake in Greece made no sense.

Decisions made in an ivory tower by EU chiefs of state and confirmations by parliaments are not enough, all by themselves, to carry the day. The strength of a commitment rests squarely on the ability of those who have accepted it to continue to deliver. Open-end compromises, as for instance the likelihood of not keeping the implied deadlines for:

• Restructuring the labor market

• Selling assets (Port of Piraeus, government land), and

• Implementing the new and tougher set of cost control measures5

work against the results expected from bailout packages. This is counterproductive. In addition, independent estimates pointed out that Greek budget figures slipped during the first bailout and the euro 130 billion of the second rescue was no longer enough to fill the financing hole faced by the government over the next three years.

“There is clearly the need for everybody to carefully look into their contributions,” said one of the senior officials involved in the negotiations. “The pieces are not yet in place to support a more aggressive strategy,” commented Mutjaba Rahman of the Eurasia Group, a risk analysis firm, “While Greece is unequivocally insolvent, Portugal is not, but it will be the next victim absent a credible firewall.”6

5.2 Aristophanes, Euroland, and Greece Today

Two bailouts are already one-too-many, and we are not yet at the end of the rescues. Is this a comedy or a tragedy? Tragedy and comedy are the same thing and they should be written by the same author, Socrates once said. But laughing is an unfamiliar concept to people who take life more seriously than it is which does not mean that there exist no human tragedies in economic crises.

A master of satiric laugh has been Aristophanes, the ancient Athenian poet and dramaturge. His approach was the laugh that cuts to pieces the stupidities of those who reign, as well as the absurdities which multiplied in the course of the 30-year Greek patricide war, at the end of the fifth century BC (incorrectly known as Peloponnesian war).

Ancient Athens had tried and failed to put together the pieces of its empire using as glue the blood of repressions. In the course of the last quarter of the fifth century BC at the theater of Dionyssos, Athenians would listen to the thunder of the laugh of Aristophanes. Tragedy was in the air, but the poet made fun of it, and the Athenian public laughed.

The satirist dramatic author denounced the contradictions into which the Athenian democracy had cornered itself, the way the silkworm does when it locks itself up in its cocoon. He spoke against the disasters of ancient Greece’s civil war, the resulting misery of the people, the blood spilled for nothing, the acts of demagogues and whereabouts of profiteers who exploited other people’s misery, the stupidities of sovereigns, and unhappiness of common citizen abused by those it (s)elected to run its fortunes.

This laugh was against the sort of things to which the Athenian public had offered itself as hostage. It was not the lyrical laugh of pleasure which springs out of love, be it that of other people, of landscapes, bees, trees, and flowers. The lyrical laugh is spontaneous, the satirical one has long roots often expressed in cartoons and mapped into comic or terrifying masks like those used in ancient Greek theaters.

It is quite interesting to note that satiric authors and cartoon designers confine their art to thoughts, matters, and actions involving their own people, not foreigners, because in their own people they find both the source of satire and the way the cure should be administered. In 2011 and 2012, however, what has been seen in the daily press of Athens is not Aristophanian satire but a low grade, unfunny criticism which has neither base nor salutary aftereffects.

In the wilder fringes of the Greek press Angela Merkel has been compared to Adolf Hitler. This is not only is highly inaccurate but as well total absurdity. In Spain, too, she is damned for being the inventor of austerity, and the picture emerging from the media is of a stubborn individual whose actions threaten the world—as if it is not Merkel who provided the bigger part of fresh money to pull up from under Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain, and Italy.

The hanging tree is not satire, it is simply ridiculous. An aberration engineered by the empty headed and politicians who do not dare to express themselves publicly but only in a circle of intimates.7 Pierre-Antoine Delhommais, of the French news magazine Le Point, is much more objective than many politicians when he asks: “Is Angela Merkel responsible:”

Delhommais answers his question by saying: “No! The party responsible is the delirious model of growth based on debt and massive real estate construction.”

• “If France registers a commercial deficit of euro 70 billion, and if its companies make products which cannot be exported?”

To the opinion of the French journalist in no way can Merkel be held responsible if manufacturing costs in France, and most particularly social costs, are way too high making French products uncompetitive in the global market. (The same is true in Greece.)

“No!” says Delhommais; “Merkel is favorable to European federalism but François Hollande, the French president, does not want to hear about transferring budgetary sovereignty.”8 And this, of course, for evident reasons.

In quite a similar way one can ask if Merkel is responsible for what has happened and continues happening with the implosion of the Greek economy. The answer has been given by Theodoros Pangalos (Section 5.1). Let me add that there is no evidence Merkel was part of the Andreas Papandreou, Costas Karamanlis Jr., and George Papandreou Jr. governments—the gang of three who brought Greece to the abyss—or that she acted as their advisor. Yet, these were the governments which ruined the Greek economy.

• Like Pericles, who launched the destructive Peloponnesian war, they were chosen by free citizens, and

• They bought votes by way of granting unsustainable entitlements, which brought Greece from one disaster to the next.

Neither is there any evidence that Merkel invented the bailout, and austerity which went with it. The talk in France is that Nicolas Sarkozy was the first to press for a rescue because of the high exposure to Greece of the French banks, and asked Christine Lagarde (then French finance minister and currently president of the IMF) to come up with a solution—which she did.9 The bailout had to involve the IMF because it contributed money as well as for its long decades of experience with rescue loans and restructuring.

Euroland probably took the wrong decision. Economists doubted that bailout funds will provide Greece with financial stability. Independent credit rating agencies have been unimpressed. On February 28, 2012 a week after the second Greek rescue package was approved, Standard & Poor’s downgraded Greece from CCC, the lowest level in its creditworthiness scale, to SD—which stands for “selective default.” That same day the ECB suspended Greek bonds from being used as collateral. Both were bad omens for the continuing bailout package.

The irony is that the second rescue package and PSI were celebrated in Brussels as milestones, with EU top brass professing that Greek default was avoided. To the contrary, critics pointed out that part of that arrangement was nothing else than new austerity measures, including higher direct and indirect taxes, such as a beefed up flat value added tax (VAT) which essentially penalized the financially weaker members of society. In addition, the new burdens were coming in a period when:

• Greek households were finding it increasingly difficult to serve their obligations to tax authorities, and

• Finance ministry officials conceded that there has been an increase in outstanding debts because of the financial crisis.

Clearer heads than those in the celebrating EU Commission made the point that the situation in Greece is a precursor of what will happen in Spain and Italy; and, later on, also in France. It is quite significant that these worries were expressed a whole year prior to February 2013 when it became evident that Italy and Spain were not far from asking for rescue via the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), through ECB’s expedient of OMT mandating purchases of useless sovereign bonds of self-wounded countries.10

Greece, Spain, and Italy have been expecting too much of the German taxpayer in terms of handouts. This is irrational because, as history shows, the citizens of each country are always inclined to first protect their own standard of living and their own future income. (Of the euro 385 billion of Greek Bailout I and Bailout II (Table 5.1), the German share will probably reach about 30 percent of this amount or over two years Germany’s intake in household taxes.11)

The way a Financial Times/Harris Poll had it, only a quarter of Germans think Greece should stay in Euroland or get more help from other countries in the currency union. Such a public verdict highlights Merkel’s domestic dilemma as she comes under pressure to agree for more time and more money for Greece to get the second bailout back on track.12 As for seeing again their money, only 26 percent of Germans believe Greece will ever repay its bailout loans.

In a democracy, public opinion weights on decisions taken by governments and the aforementioned statistics are bleak. The Financial Times/Harris Poll also found that in France opinions are mixed: 32 percent of French respondents thought Greece should leave Euroland (compared with 54 percent of Germans), but the French were as reluctant as their German counterparts to provide Athens with extra money.

In an article he published in Nice Matin, the French Daily, Philippe Bouvard, the journalist, used Aristophanes’ satire to describe what the French feel: “The Greeks are not easy-going cousins, since they refuse to satisfy the imperatives of modern democracy: The payment of taxes… industrial activity…and even affable tourist services. By tradition and culture the Greeks work only a little. No doubt they find the example in Venus of Milo, the divine protector of broken arms.”

The public mood in France is captured, in a more crude but realistic way, by a blogger on Internet who put it this way: “Euro 110 billion in 2010! What did they do with that money? Now we must loan them euro 130 billion!! If we must assist these people at 100 percent my children and grandchildren will not ever pardon me for that!!!” The exclamation marks are not the end of the blog. Its author continued his criticism in a way that would have given Aristophanes food for his satire:

… And if we were asking these demonstrators what they really want? Europe does not want to pay for these cheaters, and they know it. They can no more live on the back of it. Then what? It reminds me the attitude of pedalodreou; he knows how to criticize, but as proposing something intelligent we always wait for it.

Aristophanes would have loved this “pedalodreou.” From Papandreou Jr. to pedalodreou changes only one syllable, but there is also realism in it. The way the Junior of the political family (and president of Socialist International) talks and acts is like going in a pedalo.

5.3 State of Politics and of Sovereign Debt

In its research, the Financial Times/Harris Poll contacted 1000 adults in Britain, Germany, France, Italy, and Spain. Their opinion demonstrated that there are disagreements between northern and southern Europe over important aspects of Euroland’s management. But at the same time there is a common ground. A consensus has started to develop that things are not going the way hope had it.

The reader will probably say that what is happening in Greece, Portugal, Spain, and Italy is tragic; it is not for laughs. That’s true, but neither the highly destructive Peloponnesian war was a joke. The great merit of Aristophanes is that he has shown the absurdity of the patricide war without using words which led to another quarrel.

Satire has been the best way to wake up the public to the fact that among the elected representatives of the people are egoists and incapables. Through their lack of public conscience, they take a self-centered holiday from social reality. Pericles started a brushfire of local repressions among Athenian colonies which turned into a five ring alarm and burned to ashes the social edifice of ancient Greece.

Centuries upon centuries passed since then, and the alarm bells are now ringing for another event which has disastrous social, economic, and financial aftereffects at the same time. Living on debt has been insanity. Doing the same thing over and over but expecting different results is the act of people who have lost any sense of judgment and of government.

This is as true of strikes, rallies, and Molotov cocktails as it is of guessing progress toward competitiveness. In early September 2012 officials in Brussels estimated that the Greek Bailout II program already slipped by up to euro 20 billion since, it was agreed in February of that same year. A decision on how to fill that gap had to be made before an already-overdue euro 31 billion was distributed (finally approved at the end of October as the Greek government said that by November it will run out of money).

What is happening with the Greek bailouts which led to a long list of consequences, should serve the EU, Euroland, and ECB to wake up to the fallacy that Italy, Spain, and eventually France can be rescued. Estimates published on the cost of an uncertain bailout of these bigger economies are not reliable because they only focus on what has been so far committed in Euroland funds, which is nothing more than an entry price.

If the billions and billions of Greece’s mismanaged bailouts are taken as a basis for calculating the cost of salvaging the other self-wounded sovereigns,

Then we reach a level of roughly euro 5 trillion ($6.5 trillion) which turns the euro into dust.

That’s a worst-case scenario, but from time to time worst cases have the nasty habit of turning into real life. Some estimates, very approximate ones, made by those who would like to see a blank check signed by Germany, suggest that altogether euro 1 trillion without France, and no more than euro 1.5 trillion with France, will be enough. I look at that number as an intentional miscalculation.

A more realistic, though also approximate, estimate of rescue costs should take into account the total debt of the aforementioned countries, plus bank recapitalization. In rounded-up figures, the total debt of Italy, France, Spain, Greece, Portugal, Cyprus and Slovenia13 stands at:

| Italy | euro 2.10 trillion |

| France | euro 1.80 trillion |

| Spain | euro 0.85 trillion |

| Greece, Portugal, Cyprus, Slovenia | euro 0.75 trillion |

| euro 5.50 trillion |

This does not include bank bailouts for which could be taken as proxy the LTROs by ECB to the tune of euro 1 trillion.14 The lion’s share of all this money, which in large part will be thrown to the four winds, will be eaten up by unsuccessfully trying to sustain the status quo in standard of living in profligate economies. In addition, the large majority is contributed by Germany since the second, third, and fourth economies in Euroland find themselves at the receiving end.

• Euro 5.50 trillion plus euro 1.0 trillion (for all banks) are 340 percent of German GDP, and

• Euroland’s sovereigns who look at German money as deus ex machina prepare for themselves the deception of their life.

Theoretically, but only theoretically. Germany has been condemned to pay and pay and pay. Current thinking is best expressed by paraphrasing what Stalin said to Chou En-Lai about the North Koreans: “The Germans can indefinitely continue to finance Euroland. After all they are losing nothing but their money.”15 Practically, the probability this happens is zero-point-zero. No German government can ever propose it and survive public anger.

Compared to losses by Euroland’s sovereigns in the case Greece runs out of rescue money and stop debt payments, the numbers brought to the reader’s attention are astronomical. In May 2012 François Baroin, the former French finance minister, estimated that a Greek bankruptcy will cost the French Treasury euro 50 billion. This roughly corresponds to two years of tax intake by the French Treasury. Think about bailouts and associated bankruptcies of the magnitude we are talking about.

Always using the two Greek bailouts as a proxy, the distribution of losses changes by altering the reference made to Euroland funds, particularly those connected to guarantees by the ECB. An example is the massive withdrawal of funds from Greek banks by depositors which shows up in the TARGET2 central bank balances. By all likelihood, massive withdrawals by common citizen will spill over to Spanish and Italian central banks, making the situation of the two Club Med countries even more unattainable.

As far as overall effect of a Greek bankruptcy is concerned, Pierre Moscovici, the French finance minister, put it in this way: “Greece will provoke a contagion of the crisis whose amplitude cannot be foreseen and most likely it cannot be put under control. Think about Greece plus Spain, Italy, and France. The effects will be at least an order and a half greater than those of Greece alone.

Not only are headline costs unaffordable and unsustainable, but also costs have the nasty habit to keep on increasing leading to unpleasant surprises. When the Swiss were persuaded to join the Schengen agreement16, they were told by the EU that the annual cost will be Swiss francs 11.4 million. This was the case in the first year, but six years down the line, by 2013, the Schengen cost reached Swiss francs 114 million—an order of magnitude increase. The same is going to happen with the hugely undercapitalized banks of Euroland, and most particularly with the derelict Spanish banks.

Using LTRO as proxy, my estimate for recapitalizing Euroland’s self-wounded banks has been euro 1 trillion. This may well come short. Conservative estimates talk of a euro 400 billion to recapitalize banks—evidently including German banks—and pay deposit insurance. This is totally inadequate. Without reliable statistics which, if they exist, are kept close to the banks’ chest and the vaults of their governments, it is difficult to make realistic analysis of recapitalization requirements.

Take the Spanish banks as an example. Available numbers indicating shortage of capital are totally unreliable. They are pulled out of a hat and then massaged. The October 2012 number for recapitalization has been euro 60 billion, so said a study by a consultancy. Market players however commented that needed capital is at or beyond euro 300 billion, and even that may be an underestimate. The euro 60 billion is just the bait to catch the big fish.

Totally unclear has as well been the issue of recapitalizing foreign banks for their losses in Spain, if worse comes to worse. No numbers have been provided, but an idea of likely red ink can be obtained from reference to bank losses in Greece. The French banks losses are estimated at over euro 19.8 billion, with Crédit Agricole leading the list. Compared to this amount German banks will be losing “only” euro 4.5 billion; still a hefty amount. There are moreover the banks’ losses associated to loans to private Greek companies to the amount of euro 21 billion; and so on and so forth.

Some economists are comparing the choices facing Euroland and the IMF to those confronting the American Treasury and Federal Reserve in the days before Lehman Brothers collapsed in September 2008. The fourth largest US investment bank was at the center of tens of thousands of interconnected trades, the large majority hidden from view and difficult to value. Lehman’s balance sheet was $613 billion, before its failure. But with panic following the collapse other players had no way of knowing:

• Who were the counterparties to its risky trades, and

• Whether Lehman owed them so much money that they too might fail.

Reliable information about a sovereign’s assets and liabilities prior to even proposing a bailout is very important, particularly when a common currency area is already in the middle of debt restructuring some of its members. Mistakes in estimates jeopardize the continued provision of assistance, and all of a currency union’s members will bear the consequences of such a scenario.

The same is true of overextending the ESM and EFSF budget by way of leveraging. A significant dilution of assumed agreements would damage confidence in Euroland policies and treaties, strongly weakening incentives for national reform and consolidation measures. It will also call in question the institutional status comprising:

Aristophanes would have enjoyed writing an act about the October 2012 dispute centered on highly pessimistic views taken by the IMF on whether the (then) new Greek government can succeed where its predecessors failed. Could it truly implement economic reforms to return the country to economic growth in a rapid and thorough way? IMF’s pessimism caused friction within the Troika: The European Central Bank and European Commission believed the new Greek team of prime minister Antonis Samaras has shown a credible willingness to tackle the most intractable problems.

A month later, mid-November 2012, Euroland’s ministers of finance found it difficult to decide on authorizing the euro 31.2 billion tranche of Greek bailout. The save the day, the Bank of Greece borrowed euro 5 billion from ECB to pay euro 6.5 billion in bond’s due at that time.17

At stake was not only the euro 31.2 billion aid payment, already more than two months overdue, but the whole issue of what may happen if Spain and Italy joined the hat-in-hand folk. At stake was as well IMF’s willingness to sign off on a revised bailout extending the program two more years into 2016. EU officials said that the extension was likely to add euro 30 billion to Greece’s bailout cost, and not the least of questions asked was: Who pays?

Another critical query was and remains: What all this tells us about bailouts in Euroland at large? Martin Wolf, Financial Times’ chief economist, compared Greece to the canary in the mine: “Its plight shows that the euro zone still seeks a workable mixture of flexibility, discipline and solidarity.” The eurozone is in a form of limbo:

To Wolf’s opinion, the most powerful guarantee of Euroland survival is the costs of breaking it up: “Maybe that will prove sufficient. Yet, if the Eurozone is to be more than a grim marriage sustained by the frightening costs of dividing up assets and liabilities, it has to be built on something vastly more positive than that.”18 We will return to “something” in Chapter 6.

5.4 Restructuring Efforts Don’t Necessarily Provide Expected Results

In an environment of risk-off trades, the name of the game is capital preservation. Investors look at both the history and the prospects of a country, prior to proceed with direct investments. Debt crises scare them off, whether these investors are big corporations, insurance companies, private individuals, or pension funds on whose results tens of thousands of families depend for their living.

We must base our asset allocation not on the probabilities of choosing the right allocation, but on the consequences of choosing the wrong one, said in a 2009 speech Jack Bogle, founder and retired CEO of The Vanguard Group. As far as Greece, Portugal, Spain, and Italy are concerned, investors look at their past status and prospects, coming up with the conclusion that investing there would be the wrong allocation.

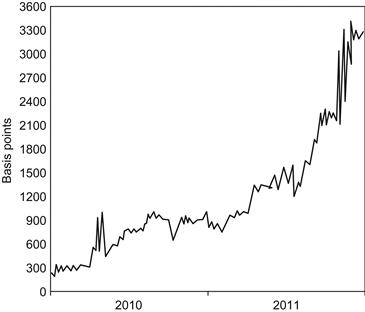

For Greece this is dramatized in Figure 5.1 through the spread of 10-year Greek government bonds against German Bunds, in 2010 and 2011 the years of the first bailout. Note that in the very beginning of 2010 the spread was not greater than 300 basis points. With the bailout discussions hitting the news, the market woke up and by April 2010 the spread zoomed past 1000 basis points. Subsequently, 2011 was a disaster as the spread past 3200 basis points. Yet Greece was already laboring under the first bailout.

That’s what the French call “the tyranny of the market,” but in this they are wrong. Nowadays the global market is composed of millions of individuals who watch over creditworthiness and market risk. Though sometimes the market may be wrong, when there is a pronounced trend, as in Figure 5.1, the way to bet is that the market is right.19 It is not easy to fool millions of individual, independent players. As Abraham Lincoln once said: “You can lie to all of the people some of the time, or some of the people all of the time, but you cannot lie to all of the people all of the time.”

So what is to be done? The answer is change in course, by living on assets not on debt, and through restructuring. To have a chance, restructuring must be done in earnest. Theoretically, since 2010 Greece had adopted extensive consolidation measures. Practically, these consisted of taxes and more taxes. There has been no restructuring of the labor market and no relaunching of the economy. Quite to the contrary, plenty of companies closed down.

Also theoretically, Greece recorded a 1.2 percent point decline in its deficit ratio in 2011. Practically, following the exceptionally sharp deficit increase in the preceding years, the budgetary deficit still stood at 9.1 percent. Greece missed the original target of 7.6 percent agreed when the bailout program was drawn up. These is no evidence that this “7.6 percent” is anything else than a random number, but 9.1 percent greatly increased the debt-to-GDP ratio.

While it is true that 2010 and 2011 were generally difficult years because of a worse-than-expected global economic environment, it is proper also to account for repeated failure by successive Greek governments to implement consolidation and reform measures. The market watched these developments and responded with ultrahigh interest rates for Greek debt postponing the country’s return to the capital markets (originally scheduled for 2012).

In the coming years, economists will be debating whether it was right or wrong that the requirements for fiscal consolidation have been relaxed discernably—by EU, ECB, and IMF—compared with the original agreements. When one goes through a bad period, and feels plenty of pain, it is wise not to relax the rules which (hopefully) lead out of the tunnel. If he does so, then the light at the end of the tunnel becomes dimmer.

Over and above the relaxation which extended the time scales, came the uncertainty about the euro’s future, and the role of Greece in it (Sections 5.5 and 5.6). John Thanassoulis, an Oxford economist who led a study of European corporate finance during the crisis, sees signs of companies positioning themselves for a break-up of the euro.20 He is not alone in this projection.21 As for the role of Greece in Euroland (debated in Chapter 6), at best it is uncertain. As long as it were still the proprietor Crédit Agricole, one of the major three French banks:

• Emptied the tills of Emporiki, its Greek subsidiary, every evening,

• Shipped the balances electronically to Paris, and

• Returned them in the morning to Emporiki, so that it is ready for business.

Crédit Agricole sold Emporiki to a Greek bank for one symbolic euro. Carrefour, the big French supermarket, sold stores in Greece also for a single euro. Other companies, too, gave up their operations in Greece, while very few increased their exposure. Alfa Beta, the supermarket, is an example. The story behind these references is disinvestment, while Greece urgently needs foreign direct investment (FDI).

As one misfortune: lack of confidence, never comes alone, inflation is present in parallel with deflation. According to Thanassoulis since banks are short of capital and their ability to lend is impaired, companies are holding prices up to preserve profit margins and have collateral for future borrowing. At the same time, companies shed full-time staff and turn to outsourcing. No wonder that Greek unemployment zoomed past 25 percent.

Some of the advice the Greek government receives looks funny. In their early September 2012 descent to Athens, the representatives of the EU, ECB, and IMF asked that the country’s citizens work six days per week,22 but left aside the issue of rising unemployment. Labor market flexibility is very important, but thought has also to be given to the fact that unemployment in Greece is now so high that there is not enough work going around for being busy three or four days per week, let alone six.

Even more dramatic is the fact that this free advice which sounds like apple pie and motherhood does not account for the base scenario that Europe and the United States are entering decades of Japanese-style economic stagnation. And there is another similitude with present-day Japan: dysfunctional politics leading to stop-gap decisions which later on corner their decision makers.

This is more or less true for every country in the old continent and constitutes one (but only one) of the reasons why the Troika does not find what it is searching for, when it reads the books of the Ministry of Finance, in Athens. The position taken by EU/ECB/IMF expressed only in too broad terms, that:

But do they bring tangible results? On February 9, 2012 Mohamed El Erian, the CEO of PIMCO, the largest bond investor world-wide, was interviewed by Richard Quest of CNN about the present and next scenes in the Greek drama. His opinion worths recording because it shows impartiality and focuses on the real problem.

“There is no common analysis, let alone understanding of what is going on,” El Erian said. “Therefore each party (the EU/ECB/IMF and Greece) has its own agenda.” The interview then turned to what a country confronted with a deep economic and financial crisis needs. El Erian’s and Quest’s opinion was that it needs not only loans but also:

Quest asked if the EU is cutting Greece off. El Erian answered that they push it to political fragmentation, pointing out that in the previous days (February 8, 2012) the meeting of Euroland’s finance ministers humiliated Greece.

To the opinion of PIMCO’s CEO there has been a shift in strategy at the vertex of Euroland, which explains the statement that the deep Greek cuts in salaries and pensions are insufficient in spite of the high unemployment which reaches 55 percent for the young (in the 16- to 25-years bracket). This new Euroland strategy can be summarized in two bullets:

It is quite likely that such a shift is taking shape. At the same time, it is no less true that Greece has a euro 250 billion economy and it is crashed by euro 350 billion in debt. When these foreign loans were made by totally incapable populist and socialist governments, the public did not react; neither did it afterward bring the wrong-doers to justice. It simply re-elected them.

“Greece is ring-fenced,” said one of the economists who participate to the research leading to this book, “This is far different than being helped to recover. Its problems are not being solved.” The position taken by the Eurogroup is different: “You have not done enough. Further work is necessary. Follow the Troika’s advice.” The Greek government’s response tells still another story: “Whatever could be done is done.”

These reactions diverge and up to a point explains the fact that the debt-to-GDP ratio continues to worsen. The EU/ECB/IMF want the Greek government to produce a primary budget surplus23 by 2013/2014. Even a blonde with dark glasses can see that this is a chimera. Neither is the two-year extension asked by the coalition government solving anything because:

Restructuring efforts don’t necessarily provide expected results, and this is particularly true when politics take the upper ground. With prices continuing going up, the common citizen is squeezed between reduction in income and inflation. The social fabric is under stress, leading many to believe that a full scale bankruptcy could have been the better alternative—from the start (Chapter 6).

5.5 Rescue Funds Can Turn into Monkey Money

If Greece achieved a primary surplus, the result the second bailout’s providers wanted to see, then this would have improved its chances to start in a path of recovery. It should not be forgotten, however, that the euro 240 billion of the first and second rescues have been loans not gifts. Even at relatively reduced interest rates, the servicing of these loans is bound to weigh heavily on the Greek government’s budget.

Therefore, it is not unlikely that Bailouts I and II will not reach their goal; and they may or may not be followed by Bailout III. Wolfgang Schäuble, the German finance minister, admitted as much when in early March 2012 said that a third package of about euro 50 billion (then $66 billion) might be necessary sometime in the future if the situation in Greece became critical.

There is no reason to believe that the same less-than expected result of bailouts will not characterize the rescues of Spain and Italy (if ever undertaken). The only difference is that the bailouts of Italy and Spain will run dry the ESM fund and explode the European Central Bank’s balance sheet. They will also change the central theme of Euroland’s debt crisis which has been that no player has been willing to:

• Recognize that trillions rather than billions of euro are needed to diffuse the debt bubble which keeps on building up, and

To start with, it is nobody’s secret that no Euroland member country, including Germany, has available the needed trillions. Along with this comes the fact that, admittedly, bailout money is unsecured money. Nobody ever said that Greece, Portugal, Spain, Italy will be able to reimburse the funds they received through rescue packages. The same is evidently true of any other country which gets into unpayable debt blues. So far in recent times in Europe only tiny Iceland and Latvia were able to redress their situation (Chapter 13), which they did:

• Without rescue packages, and

• By betting their economy’s future on hard work and an internal devaluation.

Ireland, too, is in its way of doing so, but all three are northern economies. Club Med has different standards. There is no secret about that and therefore already some of Euroland’s players have hedged their bets. The European Central Bank provides an example. While agreeing (under pressure from Euroland’s finance ministers) to forgo euro 5 billion in potential profits on its Greek bonds:

• It has protected itself against forced losses imposed on its bond holdings, and

• Will not make direct payments to the Greek sovereign whose bonds are no more accepted.24

When the Eurozone debt crisis first threatened to go out of control, the ECB ruled out taking losses on its portfolio of an estimated euro 40 billion under a Securities Markets Program” launched in May 2010 by Jean-Claude Trichet, its then governor. Subsequently, at PSI’s time, the ECB sought special protection for its Greek bond holdings by swapping them for new bonds, to be excluded from collective action clauses (see Chapter 4 on PSI). By contrast, pension funds which had (unwisely) invested in Greek government bonds lost their money.

One cannot really blame the different Euroland players (specifically those with liquid funds) for being prudent. According to many economists, even in the best case what has taken place in Euroland in terms of rescue operations could solve only part of the problem. The likelihood of a more holistic solution to Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, and Greek debilitated public finances is handicapped by:

Moreover, while western central banks flooded the market with liquidity, and big banks profited handsomely from it, loans to companies are not forthcoming. An ECB survey, published in February 2012, has shown that banks continued to tighten credit standards to readings last seen in April 2009 in the wake of Lehman’s bankruptcy. This has prevailed throughout 2012 with a rising default rate promoted by the deteriorating economic environment.

Tighter bank lending in the microeconomy is matched by concern at the marcoeconomy that temporary relief through bailouts will turn those funds to monkey money because of domestic insolvency. In a nutshell, this describes the evolving scenario in Spain and, by all evidence (given political instability) in Italy.

Self-wounded Euroland countries asking for rescues tend to forget that these funds come out of other Euroland citizens’ pockets, and the latter don’t like the idea of a transfer union. They also look at the absence of positive results given the fact that, in spite of spending billions, the debt crisis has not been averted. German, Dutch, Finnish, and other Euroland citizens believe it is not too much to ask that each of the wounded economies searches and finds its own way out of the economic chaos into which it has descended, rather than exporting:

In addition, the depth of the crisis is making structural reforms needed for long-term growth harder to agree upon. It also becomes more difficult to define and implement corrective steps, particularly as the EU tries to do it without a firm plan and a hope from getting out of the debt abyss at a predefined date. The worst-off governments say that they find it politically impossible to ask for needed structural changes, but on the other hand they fail to explain to the citizen that without a plan for recovery, and changes that go along with it, the misery years will continue.

“Summits” come and go, but they are largely love affairs and change nothing to the dismal situation. Sacred cows lead to lack of a plan and therefore of hope to get the country and the economy moving again. This is the first major concern, while the absence of truthful accounting spreadsheets mapping cost and return of rescue packages are the second. Without generally agreed solutions to both issues, there is the risk of:

In an article in the Financial Times, Professor Grezgorz Kolodko, of Poland’s Kozminski University, put it this way: We now stand at a crossroads. I think it is time to face the truth. If there is still a chance to avoid the train crash, it is not by ignoring reality and believing that the Greeks will fast as much as it takes to pay the mounting debt… Nor is it by lying and sweeping part of the challenge under the carpet, as Eurozone finance ministers and certain European Union leaders are tempted to do again and again.

But getting the whole of Euroland and each individual country, as well as its economy, moving again requires leadership, and leadership is in very short supply all over the West. If proof is needed, the difficulty to reach comprehensive decisions—and outline their consequences—is proof enough. On February 14, 2012 Rehn, the European Commission’s top economics official,

• Warned that there would be “devastating consequences” if Greece defaulted, and

• Pleaded for Eurozone governments to approve the bailout quickly.

This has been Rehn’s opinion. Precisely that same day a group of Euroland governments, particularly those which retain AAA credit ratings, made it clear that they lost faith that Greece will ever deliver its end of the bargain. “We are getting closer to default,” stated a senior Euroland official. “Germany, Finland and the Netherlands are losing patience.”25 “Until we have it all definitely on paper, with really solid guarantees from Greece as well, and legislation, we can’t make any decisions,” said Jan Kees de Jager, Dutch finance minister.26

What rattles the Euroland member states providing the funds is that a bankruptcy by recipient countries would turn their money into monkey money—admittedly not a good prospect. Neither is the drain of funds for nation-state bailouts the only game in town. As Chapter 4 brought to the reader’s attention mismanaged financial institutions, too, have an insatiable appetite for rescue money.

A sound principle in financial management, as well as in good neighborly relations, is that every country takes care of its own sick banks, who gambled and lost in the derivatives markets or kept too close to the unhealthy deadly embrace of banks and sovereigns. The United States, Britain, Germany, and Holland rescued and/or recapitalized their own banks. By contrast Spain, already at the edge of bankruptcy, wants its banks to be financed and recapitalized by Euroland—no questions asked.27

This is permanent free lunch, at its best. As John Major, the former British prime minister, had it in an article he published in the Financial Times, “The ease of (Greek) entry exemplifies the follies of the founders. France insisted: “You cannot say no to the country of Plato.” Maybe not, but every European is now paying the price…”28 The same is practically true of all other Club Med countries’ membership to the single currency.

To Major’s mind, Euroland’s Club Med member states should devalue to become competitive, but they cannot because they are locked in a single currency. And because they cannot devalue their currency, they must devalue their living standards. Promoting reforms to enhance efficiency will take years. Meanwhile, as Major has it: “Wages must fall, unemployment will rise and social unrest will increase.” And, of course, bankruptcies, too, will rise.

This is the right diagnosis, but the prescription is much more complex because it involves not only economics and finance but also (and primarily so) plenty of social issues. The global economy is not at the best of health, and Euroland is no exception to it by any means. In fact, the forecast for 2014 is that Euroland’s economy, as a whole, will grow by less than 1 percent dragged by economic problems in Southern Europe.

5.6 Using CDSs as Predictors

The concept of CDSs has been introduced in Chapter 4 in connection with credit events associated to PSI. A concise way of looking at them is as insurance policies aiming to protect their buyer against credit risk associated to the likelihood that the issuer of debt, or other financial instruments, defaults. At the same time, however, while paying for this protection the buyer assumes two new risks:

• Creditworthiness; the writer of a CDS may not be able to face its obligation, and

• The possibility that a default may be masqueraded, so that a credit event is not being declared triggering the protection payment, as it has nearly happened with PSI.

CDSs are characterized by spreads conveying to buyers and prospects a message on creditworthiness. Not all entities in the same class (sovereigns, companies) have the same quality of credit. Spreads vary as a function of time for the same entity as its financial position (hence, its chances) strengthens or wanes. If one instrument is taken as benchmark for instance German Bunds, then watching the spread of other sovereign bonds against this benchmark provides an interesting measurement.

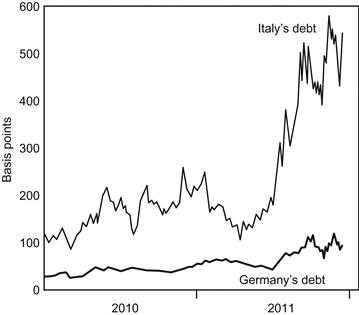

CDSs spreads in Figure 5.2 measure the likelihood of Italy’s inability to honor its debt obligations; for instance, to repay its bonds. The benchmark is German Bunds and the difference is expressed in basis points (100 basis points=1 percent). Because CDSs are tradable, they act as real-time market signals for financial anxiety associated to sovereigns, companies, or any other debtor.

Figure 5.2 Twenty-four months CDS spreads of Italian sovereign bonds against German bunds (in basis points; 100 P=1%).

The volatility of CDSs increases significantly at times of stress. Even for well-known governments (or companies) CDS spreads can easily double and then halve again within a few months. Bankers, investors, and traders look at these spreads as a warning. Even if they are not necessarily the best measurement of an entity’s intrinsic value, they are:

Investors behave like voters and CDS spreads are a vote. At end of April 2012, less than two months after the PSI and second bailout negotiations, Greek two-year bond yields (which move inversely to bond prices) jumped 133 percent—as a news item revealed that the country’s budget deficit for 2010 was 10.5 percent.29 This jump reflected market uncertainty about the Greek economy’s future.

With market uncertainty at an all-time high, the spread between Greek 10-year bonds and German Bunds of similar maturity widened to 1208 basis points, the most since data was first collected in 1998. The cost of borrowing for Portugal also reached Euroland highs, because of rising concerns that peripheral economies will be forced to restructure their debts. Many investors were keen to hedge their risks using either of the principal ways of positioning one’s portfolio against default:

The first alternative is more classical, but shorting becomes problematic with complex debt instruments. There has been, as well, a scarcity of bonds available for investors to borrow on the heels of PSI (Chapter 4). In part, this is also due to a ban in Greece on naked shorting of stocks (where investors do not own the underlying equity), leading to increasing use of CDSs.

CDSs and recovery swaps, said an expert, give banks and investors more ways and more scope to hedge their risks. At end of April 2012 outstanding gross CDS contracts of Greek, Portuguese, Spanish, and Irish debt totaled about $330 billion. The recovery swaps market also grew. Remember, however, that CDSs and recovery swaps are only activated in case of a credit event; if an issuer:

• Fails to meet coupon payments,

• Alters the terms of a bond to longer maturity,

• Changes the currency the debt is denominated in, or

• Proceeds with restructuring or reprofiling involuntary to investors.

While corporate defaults that lead to payment of CDS protection are routine, the case of sovereign credit event associated to PSI was a novelty. Traders rushed to calculate exposures. The notional value of Greek sovereign bonds insured by CDSs was between $70 and $74 billion, according to DTCC, a data repository. But banks and hedge funds have offsetting exposures, having issued some CDS insurance contracts and bought others. This saw to it that the net exposure to a Greek default was “only” $3.3 billion. Not so deadly.

Both gross and net CDS figures (the $70 to $74 billion and $3.3 billion) are important and necessary; all by themselves CDSs net figures are not transparent enough. Net figures help in calculating capital requirements, while gross figures provide the dimension as well as the basis for estimating credit risk assumed by Bank A which bought protection from Banks B, C, and D. They help to judge if anyone of them might not be able to face its obligations.

In addition, the aforementioned 1 to 22 difference between gross and net has its own risks. Largely contracted over the counter, the CDS market is opaque. Netting is done on initial values which may significantly change as events unfold. The bought-and-sold algorithm used for netting does not account for the price of these contracts. A bank which offered CDSs for Greece when the credit gap to German Bunds was 300 basis points, would pay an exorbitant price to net when the rating of Greece dropped to “CCC” and the credit gap is 1208 basis points.

As Chapter 4 brought to the reader’s attention, on March 1, 2012 the first time around the International Securities Dealers Association (ISDA) ruled that the 73.5 percent haircut on lenders by PSI (in the Greek debt), was not a credit event. But a week later, on March 9, ISDA declared a “credit event had occurred” and billions of euro of credit default insurance had to be paid out. Still, there was no market panic even if risk tends to show up where least expected. That sum seemed reasonable and manageable, it did not keep protection sellers sleepless at night.

Greece was declared to have technically defaulted, as a total of 85.8 percent of Greece’s international creditors approved the restructuring deal which reduced the value of their investments by 73.5 percent. Lucas Papademos, then Greek prime minister32, stated this was the largest restructuring even made, adding that:

• He understood the significant damage unleashed on investors, and

• The country had no right to squander the debt it had been forgiven.

Papademos promised to “modernize the country, make our economy competitive, and tidy up the state,” his government however fell afterward and all that proved to be just words. Politicians will do well to desist from promising any more than they are sure they can deliver.

In retrospect, this first experience with a risk event associated to sovereign credit event was orderly, though painful to the banks who lost nearly three-fourth of their bonds’ face value and to those who had to pay the $3.3 billion protection money. By being orderly:

• It has not created major disruptions in financial markets, and

• The settlement of CDS contracts went smoothly, thereby creating precedence.

At the same time it provided an example for a possible orchestrated sovereign restructuring. Most market participants had anticipated the default event, and plenty of contracts were unwound ahead of the largest losses for government bond investors in history.

It would, however, be wrong to conclude that all future sovereign defaults (which will definitely occur), can be organized in an orderly manner. For instance, the Spanish sovereign, a candidate for the next in line sovereign credit event, has so far kept the status of its Treasury (and that of its banks) close to its chest. Because of prevailing opaqueness, several financial analysts believe that an eventual default by the Kingdom of Spain is unlikely to be isolated and orderly.

1The Economist, July 11, 2011.

2Idem.

3This particular Eurogroup meeting had taken 13 hours.

4The four parts of PSI published by an investment bank analysis are euro 52.2; 35.5; 36 and 92.3 billion. Of the total of euro 216 billion was taken a haircut of 73.5 percent=euro 158.76 billion.

5Their nature has been explained in Chapter 4.

6Financial Times, February 7, 2012.

7As reported in the Canard Enchainé, François Hollande, the French president, said in a meeting with his ministers that Merkel is “a very selfish person”, because she did not agree to his demand to mutualize the bottomless pit of French public debt.

8Le Point, July 5, 2012.

9See also Section 5.4.

10In fact, the heated late January 2013 argument between Wolfgang Schäuble, German finance minister, and Mario Draghi, ECB’s boss, about Cyprus had little to do with Cyprus which found itself in the crossfire. The targets were Spain and Italy.

11Not counting VAT and corporate taxation.

12Financial Times, September 3, 2012.

13As we have already seen, Cyprus and Slovenia are also in the sick list.

14The LTROs took place in December 2011 and February 2012. At end of January 2013 the better off banks returned to the ECB euro 148 billion.

15What Stalin said to Chou En-Lai in plain Korean War has been: “The North Koreans can indefinitely continue fighting because they lose nothing else but their men.” Simon Sebag Montefiore “Staline”, Editions des Syrtes, Paris, 2005.

16Of free circulation of people among subscribing nations.

17November 12, 2012.

18Financial Times, February 15, 2012.

19Yield spread of Greek sovereign bonds reached 4000 basis points in early 2012, collapsing to 1600 and returning to 3000 basis points.

20The Economist, October 6, 2012

21Chorafas DN. Breaking up the euro. The end of a common currency, New York, NY: Palgrave/Macmillan; 2013.

22Le Monde, September 7, 2012.

23A budgetary surplus prior to calculating the interest to be paid for outstanding public loans.

24Later on, this decision was reversed.

25Financial Times, February 15, 2012.

26Idem.

27Unwisely, Euroland’s finance ministers approved a euro 100 billion ($130 billion) rescue package for self-wounded Spanish banks.

28Financial Times, October 27, 2011.

29The deficit was above the government’s estimate of 9.4 percent, although below the 2009 shortfall of 15.4 percent of GDP.

30Which involves borrowing a security and selling it with an agreement to buy it back at a later date.

31With recovery swaps investors bet on the haircut level in any restructuring.

32Papademos is a central banker turned politician.