Options for this Decade

Heavy public debt has been one of the most important reasons why over 5 to 6 years the economic and social structure of western society has been under stress. Unemployment zoomed and then remained at high level, while national income is lower than what would have been expected in an average recovery. This provides politicians and common citizens with three options, in line of diminishing likelihood:

• Continue meddling through hoping to buy time,

• A slow, very slow, improvement of the economy and in employment, and

• A global “perfect storm” leading to a new economic depression.

The meddling through scenarios is the more likely. Steady improvement has lower probability and is optimistic, based on the hypothesis that Euroland finds its way toward a greater economic, financial, fiscal, and political union; the US economy is improving albeit at slow pace; China has a soft landing, and many of the developing countries resume their growth; also there is no war in the Middle East.

Keywords

Economic options; defeatist slogans; debt’s daisy-chain; drift by governments; bank bailouts; financial stability; personal responsibilities; collective responsibilities

3.1 Three Main Options for the Next Years

In an interview he gave on February 8, 2013 to CNN, Mohammed El-Erian, the CEO of Pimco, said that there is a big gap between the economic fundamentals which are low and the market expectations which stand high. To Richard Quest’s question on what makes that gap, El-Erian answered that the wedge is made by central banks, their excessive liquidity and its impact. There is no better description of the bubble economy in which we live.

To the opinion of Dominique Strauss-Kahn, the real question is what will happen if the dollars drop out of the screen of global currencies. As long as confidence in the US dollar persists, even a weak level of confidence, Strauss-Kahn said in his Monte-Carlo lecture of January 18, 2013 America is able to balance its accounts with the rest of the world. But the internal problems, particularly the challenge of huge and growing deficits, continue being gigantic.

According to the former boss of the IMF, the twelfth hour accord on fiscal cliff was, so to speak, mandatory; but it was not useful. Obama gained a few months till the debt calamity hits again with a lot of unwanted consequences. On January 1, 2013 the United States avoided bankruptcy as the Republicans agreed to join in kicking the problem to a later date. Neither party, however, did much to:

Economists think that there is a deeper message hiding behind the sluggish pace of the current recovery,1 which follows the most severe recession since World War II: countries are not doing what it takes to lift themselves up. This is particularly true in western countries. Leveraging by money printing is the wrong remedy given the magnitude of the downturn.

Heavy public debt has been one of the most important reasons why over 5 to 6 years the economic and social structure of western society has been under stress. Unemployment zoomed and then remained at high level, while national income at end of 2012 was lower than what would have been expected in an average recovery. In an interview he gave to Bloomberg BusinessWeek mid-August 2012, Nouriel Roubini, the economist, stated that as far as the coming couple of years are concerned, there are three alternative scenarios.

A. Meddling through, characterized by a 55 percent probability,

B. A global “perfect storm” for 2013, with a likelihood of 35 percent, and

C. A slow, very slow, improvement of the economic situation to which Roubini gave the remaining probability of 10 percent.2

Less than a week earlier, on August 9, 2012 CNBC had conducted a poll focusing on investors’ view of the economy. Of course economists and investors are different populations and their opinions may also differ. This has indeed been the case, but still the likelihood of indecision and meddling through came up in first position, followed by a worsening projection on economic development. Here is in a nutshell this poll’s result:

• There is no change in the economy, 36 percent.

• The economy is getting worse, 34 percent.

• The economy is improving, 30 percent.3

If the first two probabilities are added together, this means that 70 percent of respondents believe the economic and financial difficulties will continue even if they fall short of global meltdown. In the latter case, which is scenario “B” in Roubini’s classification, the situation becomes disorderly with some Euroland countries defaulting while another bubble is bursting in the United States as well there is hard landing in China while other major emerging markets are stalling.4

We are told that there has been soft landing in China. But should we believe it? If yes, how can we explain that there is a big drain of capital from China, part of it heading for Africa, among all places. In addition, big part of this capital drain is made of American and Chinese capital. The answer cannot be found in an aversion to state capitalism, because this has been China’s choice since Day 1 and so far it worked alright.

Experts suggest that the rift between Beijing and Shanghai is a more believable reason. If it happens, economic disruption will be akin to the “real perfect storm,” at least an order of magnitude bigger than that of Lehman Brothers. Compared to this fear, never ending troubles in Euroland look like a joke, and the tsunami from a rift in China will hit the US economy in full force.

State Street Global Advisors, the world’s third biggest funds manager, said 71 percent of investors (in a global survey of 300) globally fear an imminent Lehman-like debacle with Asia the likely epicenter. Participants have included largest pension funds, asset managers, and private banks. Surveyed executives could give 1 or 2 reasons for the tail risk:

• 66 percent answered it would be triggered by the global economy falling into recession,

• 66 percent responded it would be caused by the break-up of the euro, and

• 20 percent said it would be created by big bank insolvency.

Others cited an oil price shock and monetary stimulus creating asset bubbles.5 The responses identified the prevailing investment market psychology and you cannot successfully fight market psychology. Of those surveyed, only 20 percent were confident they were protected against tail-risks. In 2008 “you would have been better off sticking your money under a mattress,” said a senior American assets manager. “Frankly, that could be the best strategy today, too. At least you keep your cash, and inflation is very low.”6

In contrast to the perfect storm and meddling through scenarios, option “C”, which is low probability but optimistic, is based on the hypothesis that Euroland finds its way toward a greater economic, financial, fiscal, and political union. In parallel to this, the US economy is improving, China has a soft landing, and many of the developing countries resume their growth. Also, most importantly, there is no war in the Middle East. All this takes place in what is still a bumpy road.

Scenario “C” is sustained by the hope that after 5 years of a great recession things start looking up. Not so, says Jamil Baz in an article he published in the Financial Times. To his opinion, it will take a minimum of 15 years for the economy to reach escape velocity and attain a level consistent with healthy growth. For this to become a reality, the debt overhang will need to come down very sharply.7

Baz bases his opinion on historical evidence which suggests that it is impossible to reduce debt by more than 10 percentage points per annum without social and political upheaval. What has happened in 2011 and 2012 in Greece and in 2012 in Spain corroborates Baz’ estimate, as well as his suggestion that:

• When we finally start cutting our debt, the economic impact will be massive, and

• Because of negative feedback loops between deficit cuts and growth, each country engaging in servicing debt may lose more than 20 percent of its GDP.

These are well-received points. It is reasonable enough to guess that a big chunk of this 20 percent of downsizing, in GDP terms, relates to “assets” which have been acquired through steady leveraging over 30 years till the debt became unsustainable. Behind this required deleveraging we find the:

• Impact of households repairing balance sheets,

• Persistence of weak labor markets,

• An effort toward fiscal consolidation, and

• Macroeconomic outlook across the globe surrounded by a high degree of uncertainty.

There is little doubt that the markets will continue focusing on what happens when Spain and/or Italy is (are) forced to ask for bailout and austerity measures have to be taken while the deteriorating macro picture suggest further monetary easing.8 Spikes in commodity prices may unsettle scenario “A” and tilt it toward scenario “B.” In such a situation, the best chiefs of state and central bankers can do is to stay level-headed, without engaging in absurdities by denying the facts.

3.2 “The Worst Is Over” Is a Defeatist Slogan

In an absurd way, emulating the forecast of a Merrill Lynch senior VP who a couple of months prior to the Lehman bankruptcy had said, “The worst is already behind us,” and on March 22, 2012 Mario Draghi, ECB’s president, declared, “The worst is over!” Is it really? Which is the evidence? Which are the preconditions? Is money thrown at the problem enough to solve it? What is the role of political misconduct in engineering the drift from scenario “A” to scenario “B”? (see Section 3.1).

Here is in a nutshell what I mean by political externalities and associated misconduct: In February 2012 George Papandreou, the former socialist prime minister, found the courage to say to the Greek parliament, “Our political system is collectively responsible for all the bureaucrats we have hired because of favoritism, the privileges we have accorded by law, the scandalous demands we satisfied, the syndicalists (labor unionists) and businessmen we favored and the thieves that we did not bring to prison.”9

In one well-phrased statement, expressed in lucid and focused terms, the former prime minister and socialist party leader described what is wrong with the current western democracy. All of the reasons Papandreou mentioned converge to create an impossible economic climate and a mountain of debt which will be paid by the same public who elected these second rate politicians—of the left and of the right—which means by all of us.

Forgetting about political meddling and its (sometimes) disastrous effects, and depending only on running faster, the printing presses serves in solving no economic problems whatsoever. Instead, it creates new ones and makes those already in existence even worse. Aside that fact, politicians at the vertex of the stage and governors of central banks should not allow themselves statements such as “the worst is over” because:

In early 2012, when it were made, Draghi’s statement contrasted to that of economists who, that same day, declared that Italy and Spain were big economies (the third and fourth in Euroland) and if they caved-in then the existing firewalls will not be able to contain the fire from spreading. In addition, just a day prior to “the worst is over” declaration, the message by the financial ticker on Bloomberg News was that Spain risks a default now more than ever. As for Italy, the way an article in the Economist had it, there was a near-paralysis in the country’s domestic banking system with rickety banks reluctant to lend to local firms.

In addition, timing-wise “the worst is over” came at the worst moment possible. Greece is under band aid with the Troika reluctant to release bailout funds; Portugal is uncertain about asking for second bailout; Ireland demanded delays in reimbursing its loans. Economists characterized the bailout problems, including those of Italy and Spain as intractable, while Club Med’s10 governments find it difficult to get themselves together to embrace necessary changes.

Part of staying level-headed is avoiding excessive printing of money in order to continue being all things to all people, all companies and all other sovereigns—allowing no entity to fail and salvaging even the most derelict. This is a Maginot Line mentality, a basket case of poor leadership because:

• History does not repeat itself in an exact manner, and

• Leaders who cling to past recipes are almost certain to fail.

The message all this conveys is that the future survival of the euro is in doubt while Club Med countries, which are feeling the heat of past profligate follies, are nervous. Neither should it be lost from sight that the global economy, too, is highly leveraged. At the end of 2011, global GDP was estimated to stand at $73 trillion. At that time, equity capitalization, debt instruments, and derivatives were slightly in excess of $591 trillion, with the following weights:

| Equity capitalization | $50 trillion |

| Bonds | $95 trillion |

| Derivatives | $446 trillion |

| $591 trillion |

As these numbers document, the gearing of the global virtual economy over the global real economy has reached an unprecedented 822 percent, with derivative financial instruments responsible for roughly three-fourth of that huge sum. This is creating an unbelievably large and risky overhang, documenting that the worst is by no means behind us.

“The system could work as long as there are no substantial bankruptcies,” said one of the experts, adding that precisely because of such an ultrahigh gearing, a couple of big ticket bankruptcies will precipitate a global catastrophe. To the opinion of other knowledgeable analysts, the global debt is no more manageable and if governments are so bewildered and uncertain about the “way out,” it is because the gearings of such a magnitude are unprecedented.

While the buildup of the global bubble took roughly three decades, the worst part has happened over the last dozen years. In 2000, the world’s bond market stood at $36 trillion, composed of three main parts: governments $12 trillion, financial entities $ 18 trillion (half the total), and nonfinancial entities $6 trillion. As we have just seen, at the end of 2011, the world’s debt instruments reached $95 trillion with the following approximate distribution:

• Sovereigns nearly $40 trillion, a 333-percent increase,

• Financial entities over $45 trillion, practically doubling their debt, and

• Nonfinancial companies $10 trillion, a jump of almost 167 percent.11

These are stratospheric levels of indebtedness, and they have the point of being unsustainable. The way an old proverb has it, “When you lose your way go back to the beginning and start again.” Let’s do that based on the analysis of the Great Depression by Irving Fisher, the economist. Fisher had suggested two basic conditions to escape a debt trap.

• Balance sheets of insolvent households, banks, and sovereigns must be repaired by letting them default or by a bailout, doing so as fast as possible without causing new defaults.

• Prices of assets such as bonds and real estate issued by insolvent borrowers must fall as fast as possible to levels that attract buyers and get the economy moving, but not so fast as to trigger a spiral of defaults.

Defaulting without causing new defaults could be achieved through ring-fencing, the way the British Vickers Committee suggested for retail and commercial subsidiaries versus investment banking units of big banks. The purpose of such risk-fencing is to stop contagion which is likely to damage otherwise viable enterprises. Indeed, this is what should have been done in 2008 instead of providing an unprecedented amount of public capital to the self-wounded banking industry.12

As for the first bullet’s option, given the super-leveraging which now prevails around the world, it would be absurd to contemplate bailouts at global scale because there is no ultrarich deus ex machina* to do so—like America did it for Europe with the Marshall Plan, after World War II. Both America and Europe can now depend only on their own forces.

The ultimate goal of monetary and fiscal policy in the EU should be to reengage the private sector, says Bill Gross, chief investment officer of PIMCO. Gross adds that the EU needs the private sector as a willing partner in funding its economy—a point which often gets lost in the all too frequent promises, such as the one to defend the euro made by the European Central Bank president.13 As Gross observes, however, private investors are balking.

Private investors no more accept cold economic policy pronouncements, and IOUs that make for media headlines. Fisher’s advice about allowing entities to default is sound. Freedom to enter the market and freedom to fail are, after all, pillars of capitalism. The principle of freedom to fail was broken by the George W. Bush Administration in 2008 when it intervened to “save” self-wounded big banks from bankruptcy. Freedom to fail was further destabilized by the European Union’s, ECB’s, and IMF’s 2010 “bailout” of Greece whose aftereffects threw the country in despair.

There is nothing wrong when borrowers who cannot service and repay their debts declare bankruptcy. It is up to themselves and their creditors to sort it out. Eventually, the bankrupt entity will come out of the tunnel. In the case of Argentina, it took 2 years while Greece is 3 years in the bailout tunnel and nobody can see the end of it. If governments send the fire brigade (usually the central bank) with plenty of money to put down the fire, there will be constant pressure to:

• Enlarge the limits of this firefighting, and

• Soften the bailout rules, which means making the pain longer lasting.

To participate to the common currency game, whose perceived benefits were attractive, but whose challenges proved to be enormous, sovereigns conducted secret negotiations and faked their economic data. In doing so, they were helped by investment banks and their derivatives games. The inadequacy of results being obtained underlines the inadequacy of that rigged system.

One more critical element should be brought to the reader’s attention. The western economy will not start moving again by applying cookbook solutions. New ideas are necessary, as the story of Apple Computer and other successful companies documents. Coming up from under is a great enterprise, and great enterprises need ideas which are new and vibrant, as well as the will to apply the decisions being made. In Britain, in the nineteenth century, the great idea was the empire. At end of World War II, in America, the great idea was leadership of the free nations. What’s the great idea of western countries in 2013?

3.3 The Italian Government’s Daisy-Chain

In World War II, victory bonds by the US Treasury were the source of great profits for banks because they made possible daisy-chain exploitation of money created by the Federal Reserve. To assure successful bond sales and stable interest rates, the Fed expanded bank reserves by buying up government securities. Commercial banks lent this expanded money supply to private customers who then lend it to the government by buying new Treasury bonds.

The daisy-chain continued as customers sold their new government securities to commercial banks, who (eventually) sold them back to the Fed when the central bank was again required to expand the money supply to provide the liquidity necessary for war effort. In essence, the US government was borrowing its own money, while paying a fee to the middlemen.

This is roughly what the Italian government has been doing in peace time, during the last few years. Experts say that the Italian government’s daisy-chain will become king-size with OMT (Chapter 2) which will significantly expand its present version. To appreciate this argument, the reader should know that Italian public debt is primarily incurred and funded by the central government, which uses several debt issuance venues:

• The largest portion, about 72.5 percent, is issued in the form of long-term bonds (Buoni Poliennali del Tesoro (BTPS)), presently standing at euro 1.79 billion, and

• The Italian Bills program (BOTS) fluctuates in bracket of euro 0.16 to euro 0.25 trillion, with average refinancing cycle of 5 months.

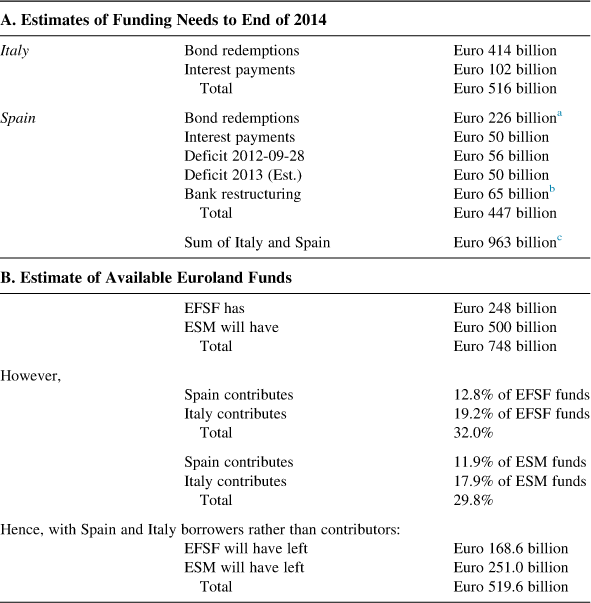

A study by UBS suggests that as far as Italy is concerned, till the end of 2014, total bond redemptions will amount to euro 414 billion while new debt resulting from fiscal deficits and interest paid on debt would be about euro 102 billion—to a total of euro 516 billion ($671 billion).14 That’s a great deal of money.

In 2012, Italy was expected, but only expected, to have a primary (before interest) budget surplus of 2.9 percent GDP. Since about 20 percent of the just mentioned “new debt” was earmarked for interest payments on the country’s huge public debt of about euro 2.1 trillion ($2.73 trillion), that amount of money eats up for breakfast the 2.9 percent primary surplus. That’s a first class example of how much money costs a high public debt policy.

Excluding any surprises, over the time frame under consideration, that is, till end of 2014, Spain is confronted with bond redemptions of euro 226 billion; interest payments of euro 50 billion (for 2 years); an estimated budget deficit in 2012 of over 5 percent with a GDP of euro 1.16 trillion amounts to over euro 61 billion. For 2013, Spain faces an estimated euro 50 billion budget deficit (probably much more) and some euro 65 billion to recapitalize its banks.15 The total is nearly euro 447 billion ($581 billion). This is an optimistic estimate of the Spanish torrent of red ink. Let’s recapitulate:

| Italy | Euro 516 billion ($671 billion) |

| Spain | Euro 452 billion ($587 billion) |

| Spain and Italy | Euro 968 billion ($1.26 trillion) |

The sum euro 963 billion is large, well above the remaining lending capacity of the EFSF (euro 248 billion) and the ESM (euro 500 billion) which still has to be funded. As the UBS study states, the total amount available in the two Euroland funds “… would be clearly insufficient to cover a full funding support program.” The reader should also appreciate that the combined EFSF and ESM capacity would be much lower if Spain and Italy were to become borrowers.

The net result of such a major switch is that the third and fourth Euroland economies will be withdrawing their contribution as guarantors and capital providers to Euroland’s support facilities. Spain currently contributes 12 percent of guarantees to the EFSF by Euroland member countries, and it would confront cash and guarantee contributions to the ESM at the level of 11.9 percent. The respective shares for Italy are 19.2 percent and 17.9 percent—to a total of 32 percent to EFSF and 29.8 percent to ESM.

Clearly, it is not Greece and Portugal who will supply the missing funds, Germany is in a state of bailout fatigue and, sometime in the future, France itself may change to become net borrower from net contributor to EFSF/ESM. With the treasury of these two Euroland salvage funds drying up, credit rating agencies will issue negative ratings on the remaining guarantor countries, which will be particularly painful news for (in alphabetic order) Austria, Finland, Germany, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands.

As Euroland core countries fall down the cliff in a deadly embrace with the profligates, the market will be unforgiving. Its reaction may well change Roubini’s scenario from “A” to “B” (Section 3.1)—a drift which could not be easily stopped. It would be silly to discount this possibility and its dramatic aftereffects.

As if these likelihoods were not enough, the September 2012 announcement of “unlimited” sovereign bond-buying by ECB through the OMT (Chapter 2) opens the way for obliterating the treasuries of EFSF, ESM, and the whole of Euroland in one go. Table 3.1 presents the stated statistics and estimates in a nutshell to help in keeping them in memory when making financial stability and investment decisions.

Table 3.1

Spain, Italy, and Their Use of EFSF and ESM Funds

Moreover, Greece, Portugal, and Ireland are already under bailout regime, hence they contribute nothing.

It follows that total EFSF and ESM available funds are well below euro 500 billion. That’s roughly half the amount needed (under best conditions) for Spanish and Italian bailouts.

The discussion about leveraging ESM lacks seriousness.

aKnown as the Greenspan–Guidotti rule (Guidotti P. remarks at G33 seminar in Bonn, Germany, March 11, 1999; Greenspan A. Currency reserves and debt, remarks before the World Bank Conference on Recent Trends in Reserves Management, Washington, DC, April 29, 1999; available at http://www.federalreserve.gov).

bThe results of the Spanish banks’ audit, released on September 28, 2012 stated that euro 59.3 billion will be needed for their recapitalization. I added to this a margin of 10 percent which I am sure will prove to be inadequate.

cUBS Chief Investment Office. The debt crisis, May 8, 2012. Statistics updated as of September 27, 2012.

None of the figures presented in this section and in Table 3.1 should come as a surprise to people warming armchairs at the European Executive, EU member state governments, and the ECB. Therefore, the recent talk that EFSF and ESM will bailout Spain and Italy is smoke and mirrors. As for the idea of leveraging their funds, this is total nonsense.

The leveraging options most often discussed involve banks and private investors. It should not escape the attention of Euroland’s chiefs of state and central bankers that a hit in the treasuries of these entities in the leveraging of EFSF and ESM can have severe consequences. Banks and private investors may buy Spanish and Italian bonds as long as they expect the ECB to play deus ex machina. When this hope fades, they would rush to the exit—at the same time and from the same door. It is not for nothing that on September 27, 2012 the Finnish government said that ESM money should be used only for bank bailouts.16

It is as well useful to remember that sovereign bond acquisitions by ECB started already in May 2010 through the SMP,17 and a quarter trillion euros has been spent under that program. In December 2011 and February 2012, the ECB also pumped more than euro 1 trillion through the LTRO at 1 percent interest. The lion’s share was taken up by Spanish and Italian banks that—rather than using that money for lending and rebuilding their balance sheet—employed to buy the debt of their governments. No wonder that, even if the economic situation is morose, in mid-2012 eurozone inflation jumped to 2.7 percent.

All this is leaving the ECB under Draghi hanging on a fork. What is happening is dereliction of duty because a central bank’s first and foremost duty is to assure that the currency under its watch does not lose its value, and that economic stability dominates. Both goals require conservative policies rather than throwing taxpayers’ money to the four winds.

Instead of statements promoting financial stability, what we hear is the noise of the western central banks’ money printing presses, as well as an interminable (pseudo) neo-Keynesian/anti-Keynesian debate which has come to dominate much of the economists’ time (and that of the media). This is a largely sterile exercise that obscures the real choices we need to examine and discuss. For instance:

• Should a Euroland (or any other) sovereign qualify for economic help if he or she does not balance, at least, its primary budget?18

• Should the hat-in-hand sovereign come up with a believable, serious plan on how to repay the debt within a period which could be negotiated but not to exceed 5–7 years, prior to be taken under Euroland’s wings?

Answers should be factual and documented, with similar challenges confronted in the past providing the evidence. Marriner Eccles, the Federal Reserve chairman in the Roosevelt years, is a good reference. He has been very careful with monetary policy because he appreciated that money can be easily printed but the productive forces of the economy grow slowly.

The result of turning the central bank’s presses overtime is inflationary, Eccles said. This is as true today as it were in the 1930s. Current money is no longer covered through any material assets. Bank notes are printed paper and knowledgeable people appreciate what this means, says Jens Weidmann, president of the Deutsche Bundesbank.

During the war years, roughly 60 percent of the federal government’s expenditures were financed through borrowing, not revenue. Eccles continually urged the Roosevelt Administration to borrow less and tax more, to finance the war from the swollen savings of consumers rather than the artificial expansion of money. (From 1940 to 1945 immediate inflation was avoided through wartime controls on wages and prices.)

To make his point that a grossly expanded money supply would become an engine of inflation, on September 18, 2012 Weidmann resorted to Goethe’s Faust. Mephistopheles provides an interesting precedence to paper money-based monetary policy as well as the potentially dangerous correlation of:

Early on in Goethe’s play Mephistopheles persuades the heavily leveraged Holy Roman Emperor to print more and more paper money, notionally backed by gold that had not been mined. This, the devil maintains, would help the emperor to solve the economic crisis confronting him. For a short time, the flood of paper money strategy works, but as more and more money is printed:

• The currency is destabilized, and

• Everybody, particularly the economically weak members of society, is worse off.

There are clearly parallels with the performance of the ECB, the Federal Reserve, Bank of England, and Bank of Japan with Goethe’s Mephistopheles. In fact, it looks as if Mephistopheles has multiplied like the head of the hydra and each of his clones landed a job with a western central bank, which allows it to destroy the currency under its jurisdiction.

3.4 Banks Did Not Deserve the Bailout

Decided by politicians who are freely spending taxpayer money, and by central bankers who just as freely print it, bank bailouts have been the extravaganza of the casino society. In America and in Europe, taxpayers felt that they were forced to salvage big banks who did not deserve it. “They should be enraged by the broken promises to Main Street and the unending protection of Wall Street,” says Neil Barofsky, a former US federal prosecutor and former special inspector general of the TARP.19

In his book Bailout,20 Barofsky reviews his argument with Timothy Geithner, the US Treasury secretary, whom he saw as over-sympathetic to Wall Street.21 Other critics agree. True enough, regulators face conflicts between their dual mandates of disciplining banks and keeping the financial system running. This, however, is no excuse for permanently turning a blind eye on cases of fraud as well as on the high stakes in gambling with derivatives and other poisonous products. Everything considered:

• Barofsky’s criticism of the close relationship between the Fed and the Treasury is well founded, and

• He is right when he says that the financial industry is inherently corrupt.

The pros answer that if there are oversights in supervision, they are there to preserve stability;22 otherwise, life will be too difficult for banks.23 By so saying, they confuse the banks with the bankers—particularly the wrongdoers. The argument that a regulator has to go soft on credit institutions, particularly during financial upheaval, is biased. Bringing to court those who deserve it, is the regulators’ obligation. As for each individual bank, it should have enough people trained to replace the incumbents prosecuted their act.

Neither is the recapitalization of wounded big banks the way to kick-start lending. The credit crunch continues as lending has become practically unavailable to small and medium enterprises (SMEs). This is, quite evidently, which is detrimental to economic growth, but it is nobody’s secret that economic growth will return on the heels of confidence.

This is an age-old principle conditioned by other, more recent developments. With globalization we have been experiencing international transmissions of credit supply shocks which impact on both credit and credit spreads. This transmission of credit supply shocks takes place by way of:

• Persistent decline in credit,

• Short to medium term decline in interest rates, and

• A parallel deterioration in the psychology of financial markets.

The noticeable, and often sharp, downsizing of loans activities is amplified by an international financial multiplier which represents the effect of contagion. While the global propagation of financial market shocks has gradually grown stronger over time, it is no less true that bankers and economists do not quite understand the complex national and worldwide effects of financial market disruptions.

True enough, the process of improving capital ratios often includes reduction of risky assets. Except loans, however, banks are not keen to reduce their assets, even those of their “assets” which have only a make-believe value. Instead, they increase them through gambling and risky speculations—games particularly favored by big banks. Ponzi games repeat themselves even if the previous tries have failed. For instance, in the United States, bundled loans are back in play at precrisis level.

• The use of low-rated debt in the funding market has returned to the pre-2007 high water mark, and

• This is fueling fears that the shadow banking system is becoming riskier and riskier.

Several types of securitized loans are prone to sudden pullbacks like the one in 2008, particularly when securitizations employ less liquid longer term “assets.” Over and above this comes the fact that in a market crisis, nearly all of the parties to a repurchasing deal would be hit. Those who care about the banking system’s stability, point out that underlying connections characterizing financial products played a critical role in the build up to the 2008 financial crisis.

• Banks used toxic assets, such as repackaged subprime loans, to secure trillions of dollars worth of cheap funding, by selling these leveraged instruments to one another.

• But when the American housing bubble burst, the banks’ trading partners refused to accept such securities as collateral, with the result that the repo market rapidly contracted.

There are good reasons why many seasoned experts, and bank regulators, are now raising their voice against the mammoth-sized banks whose empire has become uncontrollable. Sandy Weill has been an old hand in Wall Street. He is also considered as the father of the “big bank” concept, after he engineered the merger of Travellers with Citibank to form Citigroup, in the 1990s. Therefore, financial analysts pay attention to his call for breaking up the big banks.24

Weill’s advice that “small is beautiful” reinforces the ongoing discussion on the regulators proposal calling for separation of investment banking from commercial banking. “What we should probably do is go and split up investment banking from banking, have banks make commercial loans and real estate loans, have banks do something that’s not going to risk the taxpayer dollars, that’s not too big to fail,” Weill told CNBC.25

Other senior bankers, too, have made the same suggestion. The list includes the chairman of the Vickers Commission;26 John Reed, former co-chief executive of Citigroup with Sandy Weill; Phil Purcell, former chief executive of Morgan Stanley; and Tom Hoenig, director of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). Correctly, the latter has called for a richer, deeper Glass–Steagall Act.27

As boss of FDIC, Hoenig’s business is to watch out for banks sliding toward bankruptcy, try to avert it, and pay out if it happens. To his opinion, recent proposals for bank regulation have fallen short of establishing a solid regulatory environment. These include the Volcker rule,28 which bans banks from trading on their own account but not on behalf of a customer; and the Vickers Commission, in Britain, which suggested forcing banks to ring-fence their retail operations, separating them from their investment banking activities.

To confront adversity, banks also need a solid capital base. Basel III,29 by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, has established higher capital requirements aimed at making financial institutions more resilient. However, as recent demands for capital increase by well-known banks have shown, private investors are unwilling to provide the asked for capital, particularly if the entity is active in investment banking.

This dart of capital has a curious effect which is becoming another hallmark of the casino society: the manipulation of models which are supposed to be objective. Big banks with lots of rocket scientists30 in their employment, are trying to meet capital requirements by tinkering with their internal models. The aim is to make their holdings appear less risky to satisfy Basel III rules phased-in between now and 2019, but model manipulation is trickery, and therefore, it is pure nonsense.

The attempt to lie through models by downsizing the exposure which they have assumed by means of what is wrongly called “risk-weighted asset (RWA) optimization” lacks ethics. Changing the way risk weights are calculated to cut the amount of necessary capital is cheating, while optimization is a misnomer. What lies behind is buying, packaging, and selling toxic assets. Allegedly, banks are playing with the risk weights on various loans, so less capital has to be placed against them. Sometimes, this is done with and in other cases without the agreement of regulator(s).

Still another casino society practice adopted by banks is the massaging of popular indices to their profits. An example is LIBOR, which stands for London Interbank Offered Rates, a widely used benchmark with transactions in billions of dollars worldwide. Allegedly, LIBOR’s cousin the Euro Interbank Offered Rate (EIBOR) has also been the subject of tickering. The scandal was revealed in March 2012 and since then it continues to amplify.

The manipulation of LIBOR rates by Barclays, Royal Bank of Scotland, and other big banks can be traced back to the lax system of regulation which prevailed prior to the financial crisis of 2007–2013. The Barclays Bank admitted that in 2008 it was submitting false LIBOR rates and it had as accomplices in doing so other big banks.

At the time, the president of the New York Federal Reserve was Timothy Geithner whose response was to look the other way and let the case be buried. Many other central bankers have allegedly embraced what has been christened as the Geithner doctrine: the risk of causing big banks to fail, and hence undo all of the bailout efforts, froze them out of action. No attention has been paid by central bankers and regulators to the fact that:

• Each settlement on favorable terms to the wrongdoers reinforces the perception that crime pays.

• The lack prosecution for wrongdoing encourages fraudulent conduct.

The western central bankers and regulators espoused the Geithner doctrine spread the wrong kind of incentives around the world. Punishment for wrongdoing took a leave and personal accountability went alone with it. The lack of accountability for a person’s acts further reinforced the wrong incentives.

• Plenty of big banks have been involved in this LIBOR scandal and paid high penalties for it.

• In Britain, the chairman of Barclays and the CEO had to quit, and

• The European Union’s financial regulator said he will make the manipulation of benchmark rates a crime.

As the investigations continued, Barclays’ chairman and deputy governor of the Bank of England were grilled by a parliamentary committee. At the other side of North Atlantic, it emerged that the Federal Reserve of New York was by all likelihood informed of alleged manipulation of LIBOR sometime after 2007, but took no action. Ethics has taken the back seat; precisely the place where the casino society wants it to be.

3.5 Political Backing for Financial Stability Has Declined

On June 26, 2012 Sigmar Gabriel, leader of Germany’s Social Democratic Party, said the euro was “born with a congenital defect – it lacked a common budget, financial and economic policy.” Gabriel advised that Euroland’s members must pursue closer integration toward a “real fiscal union” to underpin the stability of the common currency; adding, “It would be an illusion to believe that we can create a fiscal union very quickly.”31

This is the right estimate. The surprise in Gabriel’s speech came when he threw his weight behind François Hollande, French president, and Mario Monti, Italian prime minister, in their efforts to persuade Angela Merkel to allow further “short-term” measures (read: flooding the market with liquidity) to calm the different operators. To Gabriel’s mind, the instrument of choice is the “unlimited” sovereign bond-buying by ECB—which, when it comes in “unlimited” amounts can as well be the instrument of financial destruction (OMT, Chapter 2).

Slowly but surely, however, leftist and populist politicians, who think that the way to placate the electorate is to throw money at the problem, are in the wrong track. Europe’s socialist parties are divided down the middle on this issue.

Prior to the mid-September 2012 elections in Holland political analysts suggested that, in large part, support for the Dutch Socialist Party (SP) grew because of its opposition to Euroland’s rescue policies and measures. For some time, the Dutch public has feared that they have to pay other peoples’ debts, and their country’s AAA credit rating is compromised by southern European countries’ spending habits. A traditionally Eurosceptic party, the SP had voted against:

• The Greek and Spanish rescue packages,

• The European Stability Mechanism,

In the end, SP lost the election. Political analysts say that had it come to power it would have instituted a change of regime in the Hague applying a “Holland first” policy with several positions not too different than PVV (Freedom Party), the right wing party. It should as well be remembered that the SP was opposed to the euro in 1999, but in the mid-2012 elections, it did not call for Holland to leave the common currency. The Freedom party, which was explicitly advocating an exit of the Euroland, also lost support.

The Dutch centrist parties maintained their dominant positions. No Dutch party stuck its neck out with a message to the electorate that “the euro must be saved at all cost.” The one which got more votes capitalized on the discontent of Dutch people about having good money run after bad. On the other hand, with the exception of PVV, no Dutch party revealed to the electorate that there is a deeper reason why so much money is thrown down the drain.

“The real reason for current political action is not to save the euro but to save their jobs and privileges,” says Dr. Heinrich Steinmann. The huge EU bureaucracy in Brussels is shaken by the thought that if the euro goes, the EU will fall apart, and they will lose their well-paid positions, expense accounts, and rich pensions. These are personal goals of the Brussels elite, and correlate very badly with the search for financial stability.

The “save the euro to save my job” connection is further reinforced by a financial–political complex which has interests invested in ECB’s ability to continue spitting out other people’s money. And it is further promoted by the general unwillingness of governments to make tough decisions, even if they know that tough and painful decisions are needed to stop déclinisme from gaining the upper ground all over the North Atlantic (Chapter 2).

“Save the euro to save my job” requires short-term action, which explains why many among the present political leaders of Euroland are pushing for more short-term measures while they know that they are ineffectual. In this camp, the ideas on how to spend money have no limits. Monti was the first to suggest the policy of using Euroland’s ECM, and its euro 500 billion, to buy bonds of “virtuous” countries (whatever that means). What a miracle! The “other Mario” (Draghi) was precisely of the same opinion.

Lost in the dust of missing political backing for financial stability is the fact that Italy’s and Spain’s reforms have been approved by the respective parliament only after lots of trimming and abandonment of vital restructuring measures. As a result, a mare’s nest of financial, social, and political risks remain, including litigation, social unrest, and a great deal of ineffectiveness hardly covered by rising populist rhetoric.

Spain’s economic mess is a combination of ailing banks, nearly bankrupt regions, double-dip recession, 28 percent general unemployment, 57 percent youth unemployment—and other dismal statistics which are getting worse. Regarding Spain’s budget, with popular support dropping like a stone Rajoy’s government will, has to find further savings, or additional revenue of at least euro 20 billion. This is easier said than done as the Spanish prime minister has promised not to cut pensions, while under pressure by EU/ECB/IMF the Greek government did just that to the tune of 40 percent and even the Italian government moved in the same direction.

Following ECB’s giveaway money policy of unlimited purchases of useless government bonds (OMT, Chapter 2), Spain managed to auction some short-term debt at reduced interest rate, but experts said the markets would not tolerate the ongoing uncertainty for long. By all evidence, the window of opportunity for Spain to issue debt at rates relatively mild, as they were in mid-September 2012, is closing. At that time, markets had priced-in an ECB-backed bond-buying program for Spain, but delays had a negative effect in market psychology.

In France, after the victory of the left in the presidential and parliamentary elections, little has been done to reshape French economic policy in a rational and effective way, as contrasted to doing so according to the party’s ideology. Hollande is more prone to tax than to cut costs. In his first trimester in office, he also chose the dangerous road of head-on confrontation with Germany,32 all the way:

• To ECB’s buying the sovereign bonds of Euroland’s profligate states, which is a liability, and

• To ECB’s oversight of European banks,33 a job for which the central bank and its boss are singularly unqualified.

Draghi’s fame as super-banking regulator of Euroland got particularly weakened with the scam of Monte dei Paschi di Siena, Italy’s third larger bank, of which he was regulator as president of the Bank of Italy, prior to being appointed to the ECB.

On January 17, 2013 two Bloomberg News reporters Eliza Martinuzzi and Nicholas Dunbar broke the story that in December 2008 Deutsche Bank designed a derivative instrument for Banca Monte dei Paschi. The goal was to hide the Italian bank’s losses before it sought a 1.9 billion euro ($2.6 billion) taxpayer bailout in 2009. This is the now famous Project Santorini—one of four of its kind under Draghi’s watch at Monte dei Paschi alone.

According to the law of the land, the Bank of Italy has the statutory responsibility for regulation, inspection, and control of the Italian banking industry. It does so through a powerful Auditing division (Ispettorato) which employs highly competent personnel and is always on alert. It is virtually impossible that for 5 years since fraud and deceit started till 2013 when it was revealed, the governors of the Bank of Italy were unaware of it.

The fact that a scam is left on its own devices while the Bank of Italy is alerted, is already something suspicious. Still more damaging is the fact that, as governor of Bank of Italy, Mario Draghi, did not make Monte dei Paschi disclose that scam information, neither did he call-in the prosecutors. Only in 2012, under his successor Ignazio Visco, Italian prosecutors opened a criminal investigation—one that includes the Bank of Italy.

As for Monte dei Paschi itself it searched for ways to justify its act. Its thinly veiled excuse has been that the “structured deals” were part of its “carry trade,” and were not submitted to its administrative body. Top management knew nothing about multibillion euro deals which turned sour and sank the bank. Evidently, this is a silly excuse, but it seems that it worked as long as Draghi’s Bank of Italy conveniently turned a blind eye.

Whether bank regulation should be hard or soft is one of the issues dividing northern from southern Euroland. The north is for real inspection. The south would not bother pushing the scams under the carpet.

A similar deep divide in economic thinking characterized Euroland’s forces of financial stability. Attempts to throw more money at struggling banks, or to mutualize debt of 17 countries with varying degrees of profligacy, has been anathema to northern Europeans. Those upholding the value of the currency are promoted inter alia by the Bundesbank. The Germans talk with the experience of hyperinflation they went through in 1922, and its devastating aftermath. They are joined by the Finns and the Dutch who also chose financial stability as the best monetary policy.

This dichotomy in economic thinking is the principal reason why Europe’s politicians did not commit themselves to a firm solution out of the debt crisis. As Andreas Höfert, the chief economist of UBS, comments, “On paper, certain solutions to the euro crisis may appear rather simple economically, but they look hugely complex from a political perspective. … Since the beginning of the euro crisis, 12 governments in 10 eurozone countries have already been ousted by general elections or lost confidence votes in their parliaments.”34

If tough decisions cost political careers,

Then such decisions will not be taken with the result that both the economy and the currency suffer.

It is infantile to pretend that the “European spirit” would carry the day, at the expense of hard-working people and to the benefit of the profligate. Which “European spirit?” Solidarity means reciprocity; it is not a one-way street. As for real European integration, it has proved to be a chimera. An article in the Financial Times put it in this way:

• The envisaged leap into “more Europe” is unlikely to be agreed, and

• If agreed, is likely ultimately to fail.35

The featherbedded last two generations of European citizens are unlikely to welcome further austerity till their countries come up from under. This would probably mean a series of crises. Bailouts will reach nowhere as it has already happened with Greece. Profligate countries, mismanaged banks, and people living on debt share as their credo Louis XIV’s après moi le deluge.

3.6 Reinventing Personal and Collective Irresponsibility

The majority of citizens today believe that the public has little influence on government decisions, and that the days of real democracy are past. This means that we have to reexamine the nature of the state and of its governance. In a democracy, the state exists for the individuals; not the individuals for the state. The latter option characterizes the socialist, fascist, Nazi, and Bolshevik credo which mutilates individual freedoms and reduces each individual into a cog in a big machine, degrading him or her to the level of an appendage of a mass society, where:

• Theoretically everything is for “free,” but

• Practically independent human thought and action are forbidden.

Part of the reason for this drift in western democratic values is the wave of materialism which pervades all layers of society. Another major part is the surprising absence of leadership. It looks as if only average men and women are in charge, and everything else has also become average. The breed of politicians in WWI and WWII (the Churchills, Roosevelts, and de Gaulles) is extinct. Today’s politicians are indistinguishable from bureaucrats. As Claude Adrien Helvétius (1715–1771) said long ago: Every period has its great men, and if they are lacking it invents them.

Our generation’s inventions36 are the bureaucrats—along with the personal and collective irresponsibility they represent. “Bureaucrats,” commented a Swedish executive in the course of our meeting in Stockholm, “don’t take risks. Their promotion is based on zero mistakes, and not all initiatives succeed.” To the contrary, for an active person failures are great opportunities for learning. When everything works like a clock without any problem, a real leader knows that the time of crisis is approaching.

Successful leaders neither remain inactive nor are they unpredictable when they act.37 They take calculated risks because they realize that it is much more dangerous to avoid tough decisions than to fail now and then. But they also clearly structure their priorities and carefully follow how risks under their watch develop so that timely corrective action can be taken.

The touch of leadership has been visible with all important issues. Plenty of examples exist from years past but habits, credos, skills, and ethics have changed. How did this change develop? In my research, I have found that recent generations of politicians lack three important ingredients for leadership:

• The ability to tear to pieces the information they are getting to find what lies beneath it, and

• The will to honestly study their strengths and weaknesses, prior to making up their mind on an important decision.

In his book Dereliction of Duty, H.R. McMaster points out that President Johnson’s lack of self-confidence manifested itself in a reluctance to trust those around him. Reflecting on his service in the Johnson White House, McGeorge Bundy had said, “Johnson was worried about the unknown…”

• “He knew how many unknowns there were,

• “He knew how complicated and uncertain life was,

• “He knew that the only way to avoid failure was to put yourself on guard ….”38

Michael Forrestal, a White House special assistant, had this to say about Lyndon Johnson which applies to most present-day politicians: “There was a bad thing in this period. The government was extremely scared of itself. There was tremendous nervousness that if you expressed an opinion it might somehow leak out…and the president would be furious and everyone’s head would be cut off…It inhibited an exchange of information and prevented the president from getting a lot of the facts that he should have had.”39

In violation to sound management practice, people were unable to disagree with what they felt were Johnson’s choices.40 This led to the desire to demonstrate unity by coordinating positions before discussing them with the president. This unavoidably leads to serious errors. The last thing a president needs is to be confronted with a unanimous view. He has to hear disagreement. Only then can he use his own judgment in examining a range of options.

I had the privilege to work for 16 years as personal consultant to the president and CEO of one of Europe’s largest industrial and financial groups. His policy in regard to decision making at the vertex was precisely the opposite to Johnson’s. He wanted his immediate assistants, presidents and general managers of his banks and manufacturing companies, to come to board meetings without any prediscussions:

• Everyone had to present and defend his or her thesis on the topic of the meeting.

• Parties with opposing viewpoints had to debate their differences in front of everyone else.

• Even a suspicion of having prearranged positions was a negative to every person who took part in it.

To Carlo Pesenti’s opinion, bringing up every issue, including its externalities, was the only way to see clearer in a situation. He was more interested to discover how well thought-out were the decisions of his immediate assistants than wait and see if they turned to be “right” or “wrong.” Something can happen turning on their head otherwise well-documented hypotheses, but lightly made business assumptions will always be a loser.

The mind of Alfred Sloan, the legendary boss of General Motors, worked the same way. He wanted to see and hear dissention. Otherwise, he would delay the board decision to the next meeting. By contrast, weak CEOs, like Lyndon Johnson, try to cover their shortcomings by distributing fountain pens, or other highly expensive goodies, such as the twin monsters Medicare and Medicaid, which lack a sense of cost control and threaten to sink the American economy.41

The search for unanimous view, which is typically based on compromises, is that of the weak, not of leaders. In the majority of cases, it locks itself up in a one-way street and from there to disaster. That’s precisely where we are today with the different European Union “summits.” There is a long list of issues on which disagreements exist, but without the appropriate analysis of pros and cons, which are brought to public attention so that they can be discussed as democratic values require, decisions are taken through power politics.

Jens Weidmann was criticized as lone wolf when he voted against ECB’s “unlimited” buying of sovereign bonds. Curiously, very curiously, dissent was muted. No other member of the central bank’s executive board fulfilled his or her duty of examination by asking:

• Is the ECB turning the monetary union into a debt community with unlimited liability by buying government bonds?

• Where is the factual estimate of the depth of the commitment in money terms and on its effect on financial stability?

• Are we able to reconcile spending big money on profligate states, when we know that all 17 Euroland countries need huge financial resources for an aging population—from retirement to health care?

• What if we have it all wrong and the ultimate outcome for Euroland’s economy resembles a Japan-like scenario of two decades of stagnation, or worse?

Just as an example, the aging of western populations and rapid rise in health care costs mean that sovereign budget gimmicks which worked in the past cannot work in the future. In fact, a major reason for the deficits which incurred and continue to incur in Club Med countries have their origin in the aging of their population and associated to it:

Both are unaffordable. The debt crisis has not gone away because the ECB (incorrectly) decided to buy sovereign bonds. Neither has the bad news run its course. As Section 3.1 brought to the reader’s attention with Roubinis’ three scenarios, it may well be that the worst is still to come, and this should discourage politicians and central bankers from spending funds reserved for the worst case.

3.7 Conclusions

When governments forget about the growing array of their obligations, and the costs these represent, which have to be weighted against receipts, then funds set to general public will be dissipated at no time. What follows in terms of rush decisions is piling error upon error. When this happens, debt and fiscal policy is far from being an example of political and social strength, and sometimes down the line the rescue mechanism breaks into pieces.

For over 6 years, since July 2007 when the global economic, financial, and banking crisis began with the subprimes, the western world has seen average annual government deficits skyrocket from 1.5 percent to 6.5 percent of GDP.42 By ballooning the cost of the western countries social safety net while confronted with reduced tax receipts, governments turned the tables on sound management of the economy.

The result has not only been that the rich got richer but also, and most regretfully, that the western middle class has been decimated. As I had the opportunity to explain in previous books, the government-run State Supermarket, into which has grown the nanny state, is simultaneously confronted by:

• Rapidly rising health care costs,

• Unfunded pension obligations,

• Upward racing costs for university education “for all,” and

• A large public sector characterized by low productivity but high expenditures.

The net result is a decline in sovereign sustenance, and this reflects in an important way upon the western nations’ creditworthiness. The vicious cycle of debt piling upon debt and error upon error is sealed by the sovereign’s loss of risk-free status, as it has happened with the downgrades of the United States, France, Austria, and other western nations. This is a sort of drift which undermines financial stability and leads to contagion.

From the standpoint of sound management, an independent country must have adequacy of international reserves. The way to judge such adequacy is by comparing its reserves against benchmarks calibrated by the collective experience of countries in past crises, and modeled through a cost-benefit analysis. Adequacy metrics described in an article by the ECB43 call for coverage by international reserves of at least:

• 100 percent of short-term debt at remaining maturity,44

The ECB article notes that IMF has recently proposed still another metric which involves benchmarking international reserves against a risk-weighted liability stock. This should capture all potential drains on reserves, weighted against the likelihood of their occurrence derived from a tail-event analysis of past foreign exchange market pressure. I would be inclined adding to that the effect of recent estimates by international agencies. For instance, in January 2012 the World Bank stated that a new oil shock will lead to hard landing.45

Each of the options we have considered is likely to have unwanted consequences which cannot be smoothed over by word-of-mouth assurances as substitute to hard facts. False assurances are by no means recent inventions. As Talleyrand said to Napoleon, “The art of diplomacy consists of masking one’s plan by verbs.”

*It means “god from a scaffolding”, an artifice. In ancient greek tragedy a machine was used to bring actors playing god into the stage.

1Such a slow recovery compares poorly to the average recovery time over the last three decades.

2Bloomberg BusinessWeek, August 13–26, 2012.

3CNBC, August 9, 2012.

4These were the words Roubini used in his Bloomberg Business Week article, mid-August 2012.

5Financial Times, September 27, 2012.

6Idem.

7Financial Times, July 12, 2012.

8Even if bond spreads are zero across Euroland, Britain, and the United States.

9Le Canard Enchainé, September 19, 2012. As I never tire repeating “Le Canard” is not a satirical paper. It’s a well-informed political weekly communicating with its readers through both cartoons and hard facts.

10Spain, Portugal, Italy, Greece, and eventually France.

11UBS, Wealth Management Research, December 19, 2011.

12Particularly the big entities which pose systemic risk. In 2011, John Paulson’s hedge fund lost more money than JPMorgan’s London unit. Regulators didn’t worry, because Paulson’s private partnership was not too big to fail.

13Financial Times, August 7, 2012.

14UBS Chief Investment Office. The debt crisis, May 8, 2012. Statistics updated as of September 27, 2012.

15Which by all likelihood is also an underestimate.

16Bloomberg News, September 27, 2012.

17SMP has been phased out with OMT.

18Its annual budget without counting the interest paid on past debts.

19The US financial bailout fund.

20Barofsky N. Bailout. An inside account of how Washington abandoned Main Street while rescuing Wall Street. New York, NY: Free Press; 2012.

21Particularly when, in the George W. Bush years, Geithner was president of the New York Federal Reserve. Notice that during that time Geithner allegedly approved the manipulation of LIBOR which led to the LIBOR scandal of 2012.

22Let me laugh.

23No kidding.

24With that merger, Weill created a sprawling conglomerate. Commenting on his call to spin off businesses and abolish the financial supermarket concept, Weill said, “I think the earlier model was right for that time.”

25Financial Times, July 26, 2012.

26Originally the Vickers Commission, in Britain, was proposing breaking up the big banks, but this finding curiously disappeared from its final report—allegedly under the pressure of lobbyists.

27The Glass–Steagall Act, passed after the Great Depression, forced a separation of commercial and retail banking from investment banking. It was repealed in 1999 by Bill Clinton, in his last year in the White House.

28Named after Dr. Paul Volcker, former chairman of the Fed.

29Chorafas DN. Basel III, the devil and global banking. London: Palgrave/Macmillan; 2012.

30Chorafas DN. Rocket scientists in banking. London and Dublin: Lafferty Publications; 1995.

31Financial Times, June 27, 2012.

32Which defeats the very purpose of the European Union.

33In the context of a very poorly studied banking union. The timetable has been pushed from an original implementation deadline of late 2012 out to early 2014.

34UBS Investor’s Guide, July 6, 2012.

35Financial Times, June 27, 2012.

36Or, rather, reinvention since the mighty bureaucracy was invented with the Mandarin culture in China and reinvented by the Byzantines.

37In his biography of Stalin (Staline. Paris: Editions des Syrtes; 2005) Simon Sebag Montefiore says that the Russian dictator misjudged Hitler because he was an admirer of Bismarck and passionate reader of Bismarck’s works. Bismarck was predictable and Stalin thought all German political leaders are predictable. Hitler was neither German, nor predictable.

38McMaster HR. Dereliction of duty. New York, NY: Harper Perennial; 1997.

39Michael Forestal, Oral History Transcript, November 3, 1969, MBJ Library.

40To the contrary Alfred Sloan, chairman and CEO of General Motors, would not accept that his assistants or board members had a unanimous opinion. He wanted to see and hear dissent.

41The same is true with the unaffordable Obamacare, which comes as no surprise as Barack Obama is a sort of Lyndon Johnson “bis.”

42Bank for International Settlements, 82nd Annual Report, Basel, June 24, 2012.

43ECB Monthly Bulletin, June 2012.

44Known as the Greenspan–Guidotti rule (Guidotti P, remarks at G33 seminar in Bonn, Germany, March 11, 1999; Greenspan A, Currency reserves and debt, remarks before the World Bank Conference on Recent Trends in Reserves Management, Washington, DC, April 29, 1999; available at http://www.federalreserve.gov).

45Bloomberg News, January 18, 2012.