To tie it all together, let's build a simple command-line notebook application. This is a fairly simple task, so we won't be experimenting with multiple packages. We will, however, see common usage of classes, functions, methods, and docstrings.

Let's start with a quick analysis: Notes are short memos stored in a notebook. Each note should record the day it was written and can have tags added for easy querying. It should be possible to modify notes. We also need to be able to search for notes. All of this should be done from the command-line.

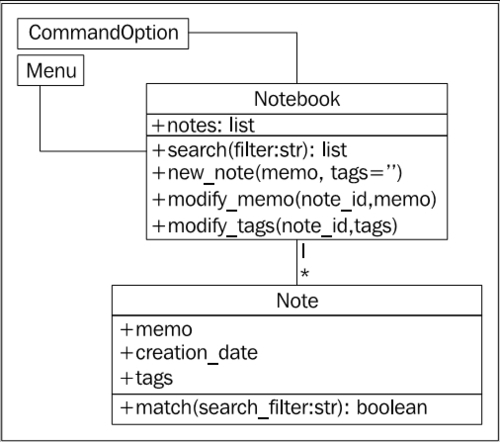

The obvious object is the Note. Less obvious is a Notebook container object. Tags and dates also seem to be objects, but we can use dates from Python's standard library and a comma-separated string for tags. To avoid complexity at this point, let's not define separate classes for these objects.

Note objects have attributes for the memo itself, tags, and a creation_date. Each note will also need a unique integer id, so that users can select them in a menu interface. Notes could have a method to modify note content and another for tags, or we could just let the notebook access those attributes directly. To make searching easier, we should put a match method on the Note. This method will accept a string and can tell us if a note matches the string without accessing the attributes directly. That way, if we want to modify the search parameters (to search tags instead of note contents, for example, or to make the search case-insensitive), we only have to do it in one place.

The Notebook obviously has the list of notes as an attribute. It will also need a search method that returns a list of filtered notes.

But how do we interact with these objects? We've specified a command-line app, which can either mean we run the program with different options to add or edit commands, or we could have some kind of a menu that allows us to pick different things to do to the notebook. It would be nice if we could design it so that either interface was allowed, or we could add other interfaces such as a GUI toolkit or a web-based interface in the future.

As a design decision, we'll implement the menu interface now, but will keep the command-line options version in mind to ensure we design our Notebook class with extensibility in mind.

So if we have two command-line interfaces each interacting with the Notebook, then Notebook is going to need some methods for them to interact with. We'll need to be able to add a new note, and modify an existing note by id, in addition to the search method we've already discussed. The interfaces will also need to be able to list all notes, but they can do that by accessing the notes list attribute directly.

We may be missing a few details, but that gives us a really good overview of the code we need to write. We can summarize all this in a simple class diagram:

Before writing any code, let's define the folder structure for this project. The menu interface should clearly be in its own module, since it will be an executable script, and we may have other executable scripts accessing the notebook in the future. The Notebook and Note objects can live together in one module. These modules can both exist in the same top-level directory without having to put them in a package. An empty command_option.py module can help remind us in the future that we were planning to add new user interfaces.

parent_directory/ notebook.py menu.py command_option.py

Now, on to the code. Let's start by defining the Note class, as it seems simplest. The following example presents Note in its entirety. Docstrings within the example explain how it all fits together.

import datetime # Store the next available id for all new notes last_id = 0 class Note: '''Represent a note in the notebook. Match against a string in searches and store tags for each note.''' def __init__(self, memo, tags=''): '''initialize a note with memo and optional space-separated tags. Automatically set the note's creation date and a unique id.''' self.memo = memo self.tags = tags self.creation_date = datetime.date.today() global last_id last_id += 1 self.id = last_id def match(self, filter): '''Determine if this note matches the filter text. Return True if it matches, False otherwise. Search is case sensitive and matches both text and tags.''' return filter in self.memo or filter in self.tags

Before continuing, we should quickly fire up the interactive interpreter and test our code so far. Test frequently and often, because things never work the way you expect them to. Indeed, when I tested my first version of this example I found out I had forgotten the self argument in the match function! We'll discuss automated testing in Chapter 10; for now, it suffices to check a few things using the interpreter:

>>> from notebook import Note

>>> n1 = Note("hello first")

>>> n2 = Note("hello again")

>>> n1.id

1

>>> n2.id

2

>>> n1.match('hello')

True

>>> n2.match('second')

False

>>>

It looks like everything is behaving as expected. Let's create our notebook next:

class Notebook: '''Represent a collection of notes that can be tagged, modified, and searched.''' def __init__(self): '''Initialize a notebook with an empty list.''' self.notes = [] def new_note(self, memo, tags=''): '''Create a new note and add it to the list.''' self.notes.append(Note(memo, tags)) def modify_memo(self, note_id, memo): '''Find the note with the given id and change its memo to the given value.''' for note in self.notes: if note.id == note_id: note.memo = memo break def modify_tags(self, note_id, tags): '''Find the note with the given id and change its tags to the given value.''' for note in self.notes: if note.id == note_id: note.tags = tags break def search(self, filter): '''Find all notes that match the given filter string.''' return [note for note in self.notes if note.match(filter)]

We'll clean that up in a minute. First let's test it to make sure it works:

>>> from notebook import Note, Notebook

>>> n = Notebook()

>>> n.new_note("hello world")

>>> n.new_note("hello again")

>>> n.notes

[<notebook.Note object at 0xb730a78c>, <notebook.Note object at

0xb73103ac>]

>>> n.notes[0].id

1

>>> n.notes[1].id

2

>>> n.notes[0].memo

'hello world'

>>> n.search("hello")

[<notebook.Note object at 0xb730a78c>, <notebook.Note object at

0xb73103ac>]

>>> n.search("world")

[<notebook.Note object at 0xb730a78c>]

>>> n.modify_memo(1, "hi world")

>>> n.notes[0].memo

'hi world'

>>>

It does work. The code is a little messy though; our modify_tags and modify_memo methods are almost identical. That's not good coding practice. Let's see if we can fix it.

Both methods are trying to identify the note with a given id before doing something to that note. So let's add a method to locate the note with a specific id. We'll prefix the method name with an underscore to suggest that the method is for internal use only, but of course, our menu interface can access the method if it wants to.

def _find_note(self, note_id): '''Locate the note with the given id.''' for note in self.notes: if note.id == note_id: return note return None def modify_memo(self, note_id, memo): '''Find the note with the given id and change its memo to the given value.''' self._find_note(note_id).memo = memo

That should work for now; let's have a look at the menu interface. The interface simply needs to present a menu and allow the user to input choices. Here's a first try:

import sys

from notebook import Notebook, Note

class Menu:

'''Display a menu and respond to choices when run.'''

def __init__(self):

self.notebook = Notebook()

self.choices = {

"1": self.show_notes,

"2": self.search_notes,

"3": self.add_note,

"4": self.modify_note,

"5": self.quit

}

def display_menu(self):

print("""

Notebook Menu

1. Show all Notes

2. Search Notes

3. Add Note

4. Modify Note

5. Quit

""")

def run(self):

'''Display the menu and respond to choices.'''

while True:

self.display_menu()

choice = input("Enter an option: ")

action = self.choices.get(choice)

if action:

action()

else:

print("{0} is not a valid choice".format(choice))

def show_notes(self, notes=None):

if not notes:

notes = self.notebook.notes

for note in notes:

print("{0}: {1}

{2}".format(

note.id, note.tags, note.memo))

def search_notes(self):

filter = input("Search for: ")

notes = self.notebook.search(filter)

self.show_notes(notes)

def add_note(self):

memo = input("Enter a memo: ")

self.notebook.new_note(memo)

print("Your note has been added.")

def modify_note(self):

id = input("Enter a note id: ")

memo = input("Enter a memo: ")

tags = input("Enter tags: ")

if memo:

self.notebook.modify_memo(id, memo)

if tags:

self.notebook.modify_tags(id, tags)

def quit(self):

print("Thank you for using your notebook today.")

sys.exit(0)

if __name__ == "__main__":

Menu().run()

This code first imports the notebook objects using an absolute import. Relative imports wouldn't work because we haven't placed our code inside a package. The Menu class's run method repeatedly displays a menu and responds to choices by calling functions on the notebook. This is done using an idiom that is rather peculiar to Python. The choices entered by the user are strings. In the menu's __init__ we create a dictionary that maps strings to functions on the menu object itself. Then when the user makes a choice, we retrieve the object from the dictionary. The action variable actually refers to a specific method and is called by appending empty brackets (since none of the methods require parameters) to the variable. Of course, the user might have entered an inappropriate choice, so we check if the action really exists before calling it.

The various methods each request user input and call appropriate methods on the Notebook object associated with it. For the search implementation, we notice that after we've filtered the notes, we need to show them. So we make the show_notes function serve double duty; it accepts an optional notes parameter. If it's supplied, it displays only the filtered notes, but if it's not, it displays all notes. Since the notes parameter is optional, show_notes can still be called with no parameters as an empty menu item.

If we test this code, we'll find that modifying notes doesn't work. There are two bugs, namely:

- The notebook crashes when we enter a note id that does not exist. We should never trust our users to enter correct data!

- Even if we enter a correct id, it will crash because the note ids are integers, but our menu is passing a string.

The latter bug can be solved by modifying the Notebook class's _find_note method to compare the values using strings instead of the integers stored in the note, as follows:

def _find_note(self, note_id): '''Locate the note with the given id.''' for note in self.notes: if str(note.id) == str(note_id): return note return None

We simply convert both the input (note_id) and the note's id to strings before comparing them. We could also convert the input to an integer, but then we'd have trouble if the user had entered the letter "a" instead of the number "1".

The problem with users entering note ids that don't exist can be fixed by changing the two modify methods on the notebook to check if _find_note returned a note or not, like this:

def modify_memo(self, note_id, memo): '''Find the note with the given id and change its memo to the given value.''' note = self._find_note(note_id) if note: note.memo = memo return True return False

This method has been updated to return True or False, depending on whether a note has been found. The menu could use this return value to display an error if the user entered an invalid note. This code is a bit unwieldy though; it would look a bit better if it raised an exception instead. We'll cover those in Chapter 4.