In This Chapter

Getting the international mix right

Making the most of national differences

Finding the information you need

Using currency differentials

We've got a global economy in which every country's fortunes are linked in some way or other with all the others. And a global electronic investment structure which allows you to put your money into almost any company of your choice, no matter where it might be. Not to mention a tax regime in Britain which is being steadily loosened up so as to let you get the full benefit of tax-efficient investment in a growing number of countries. So what could be more natural than to feel like spreading your wings and investing a little of your cash in some of these less familiar places? Even a beginner can do it.

But first, let's put your mind at rest on one important point. You don't need to have any special language skills to buy foreign investments these days. The chances are that every company you're likely to be interested in has an English-language section on its website – and if you buy its shares through the London Stock Exchange (which is often possible), you get the same transparency and investor protection as for any UK share.

If you still don't feel up to the task of going international alone, hundreds of managed funds enable you to take a stake in another country without getting up to your neck in complications. And these days, London-listed Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs) make international investing twice as easy because they're just like shares – but with no stamp duty!

You don't have to think too much to realise that pegging your investment fortune to the fate of the London Stock Exchange (LSE) is limiting yourself just a little. You must have noticed that countries' economies often move at different rates. So doesn't the logic follow that, by taking an interest in a few items from those countries, you can insulate yourself from some of the ups and downs of the British market?

Besides, as I've said, investing in foreign stock markets is such a simple matter these days. All you need is a suitable kind of trading account with one of the main execution-only stockbroking firms(that's a broker that doesn't actually give you advice, just buys and sells things when you tell it to). Running the account may typically cost you £30 a year in charges, although at the moment you can get an account for nothing with some of the online brokers.

A lot of the time, you don't need to set up anything so complicated. The range of foreign-company stocks that you can buy into in London may amaze you, because they have dual or multiple listings that make them available on more than one market at a time. So although the shares you see in the Financial Times or on the London Stock exchange website are listed in euros, or dollars, or whatever, the price you pay is in sterling. And because the shares are listed according to London's rules, the level of investor protection you get is just the same as if you're buying ICI.

Note

You're more or less forced to go 'offshore' if your interests extend to certain types of company. You don't find very many gold and diamond mining companies in the LSE's main-market listings, because most of the best and most interesting ones are listed only in Canada, America, Australia, or South Africa. (Although the higher-risk Alternative Investment Market, or AIM, will give you a fair selection of the racier companies.) If you're looking for clothing manufacturers or sugar producers or alternative energy companies, you're probably going to struggle to come up with many leading names in London, because they tend to be based in low-cost manufacturing centres. (Some clothing companies are on AIM, but otherwise you're restricted to top-end producers like Burberry if you don't fancy going offshore.)

Don't forget, too, that even if you don't feel like going the whole hog and buying shares directly, you can get some exposure to foreign stock markets by buying either investment trusts with a regional bias, or perhaps Exchange-Traded funds. ETF operators like Lyxor (a subsidiary of the French AXA group) or iShares (part of Barclays International) can sell you what is effectively a tracker fund that shadows the movement of a foreign stock market's main indices. I examine tracker funds in more detail in Chapter 14.

I describe ETFs in more detail in Chapters 13 and 14. For the moment, though, all you need to know is that you buy and sell an ETF on the London Stock exchange, just like any other share. You can put it into a tax-efficient savings plan like an Individual Savings Account (ISA) or a Self-Invested Pension Policy (SIPP). Unlike the unit trusts and investment trusts (Chapter 14 covers these) that you may be using already for your pension and savings funds, you don't pay any joining fees or management fees. You also don't have any problems selling an ETF, even on the spur of the moment, because the ETF markets are very liquid (that is, enough people are always out there ready to buy ETFs, so you never need to worry about getting stuck with them). And, perhaps best of all, you don't pay any stamp duty when you buy an ETF – just the dealer's commission, which may be as low as £5, and a very small 'spread' between the buying and selling price that's rarely as much as 0.1 per cent.

The main reason I enjoy trading in foreign shares is that they offer me a way of escaping the strictures of the UK investment scene. There have been so many times in recent decades when Britain's economy has seemed to be falling while America's has been soaring – or vice versa! So many occasions when the euro has seemed so cheap that it was bound to rebound, with massively beneficial effects on my European shareholdings. Not that we should try and draw up any hard and fast rules about this, of course, because one year's growth market can all too quickly become the next year's problem area. But you get my point.

In short, I'm convinced that a judicious mix of international stocks can provide your portfolio with shock absorbers to help it weather a bout of stormy weather at home.

What sort of storms am I thinking of? Well, I talk in Chapter 3 about the way in which economic cycles affect whole economies, and in Chapter 13 you can also find a brief analysis of how these cycles work on the commodities markets that supply raw materials to the world's manufacturers. What I'm driving at is that the various markets and economies of the world are never in completely stationary relationships to each other. Instead, they rub up and down against each other as their various fortunes improve and deteriorate – and, with only a little guesswork, you can often figure out which ones may be in the ascendant next.

All well and good. But this is sweeping stuff. How can you get all this underlying economic information, ideally in a format that applies regular statistical criteria across a range of countries? Probably the best place to start is business magazines like The Economist, whose back pages are filled with cross-border comparative material (also available at www.economist.com). But if you don't have an Economist subscription and you need a free supply of carefully crafted information, try the IMF website (www.imf.org) or the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (www.oecd.org) for the latest on economic trends.

You may, not surprisingly, decide to keep your foreign investments safely restricted to the very big stock markets – America, Germany, Canada, Australia, or perhaps Japan. After all, those are the countries where you probably feel safest. They have their share of problems, of course, but what they also have are very large domestic shareholder bases – that's to say, very large numbers of their own citizens are direct investors, so you know that there's always likely to be enough market activity going on to avoid big 'liquidity squeezes' – the times when nobody is either buying or selling shares, and when share prices can go a little stir-crazy as a result.

You probably don't fancy the idea of stock-picking in a country whose language you don't speak. (Although, in practice, you may be amazed at how many emerging-market companies have English-language sections on their websites.) And you're probably feeling rather wary of investing your money in a country where the stock market rules may not be the same as yours.

Rightly so! How would you feel if it turned out that insider trading was tolerated in the country you'd just bought into? Or if you didn't get your dividends because you were a foreigner? Or simply that you didn't know the 'inside track' of the business environment, so that your chosen company came off worse in a race with one of its rivals?

For all of these reasons, you're better off investing through a fund rather than going international yourself, if it's the less-developed stock markets that especially interest you. Even in today's electronically linked markets, the chances are that you'll be at a disadvantage to the locals at least some of the time.

Inevitably you want to keep track of your foreign investments. If you don't have time to regularly read one of the financial heavyweight newspapers, or to keep your nose permanently pressed to your computer screen, you need to look elsewhere for the information you want.

The FT online (markets.ft.com/markets/overview.asp) is one of the very best comparison sites. It allows you to survey a range of big-picture economic and investment criteria and provides breakdowns for stock markets, currencies, bonds, and commodities.

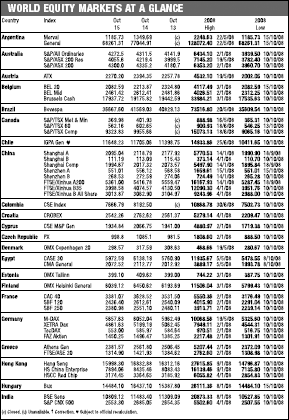

You can, for instance, get a daily facsimile of the FT's listings of all the dominant stock market indices of the world (see Chapter 3 on indices), showing you where those indices have been heading over the last few days and telling you what the 12-month highs and lows have been — see Figure 11-1.

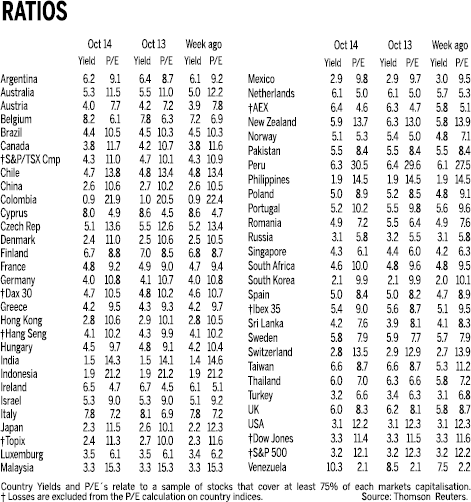

But Figure 11-1 is a strangely unhelpful chart, considering the amount of detail it contains. It only really helps you if you're already familiar with each of the indices you're interested in, and if you've been following them really closely. My personal choice instead is the chart in Figure 11-2, which shows you the key ratios for each of the most important global markets: the price/earnings ratio and the dividend yield.

Oddly, this chart doesn't specify which of the various stock market indices for each country it's actually talking about. Instead, it describes its content simply as 'a sample of stocks that cover at least 75 per cent of each market's capitalisation' (that is, at least three-quarters of the total value of the stock markets concerned).

I have no idea how many individual calculations go into those daily computations of the average price/earnings ratios and dividend yields in all those countries, but the number must be absolutely mind-boggling. The effort required to research and calculate the average p/e from 75 per cent of the London Stock Exchange's shares (by size) every day stretches anyone's computer skills; but to do it for 60 or so different markets, many of which don't record their results in anything like the same degree of detail as London, is a mighty achievement.

Comparison charts are a reasonable start for monitoring your foreign investments. But unless you're investing in a tracker that shadows a whole stock market index, such a chart isn't exactly going to give you everything you want. Where are you going to get the information you need about individual companies?

Unfortunately, for companies with foreign bases, the FT's excellent online resources don't always do the job. If you look up the FT's news reports for even a German company, let alone a Chinese one, you might very well draw a blank because often the information's not there. Nor do you find very much recent news on the London Stock Exchange website (www.londonstockexchange.co.uk), although you can find good charts that go back five years. (To go even further back, you're probably better off with the FT's 'interactive charting' facility, which reaches as much as 20 years into the past, even for non-UK companies)

Tip

Yahoo!'s UK finance site (http://uk.finance.yahoo.com) gives you a complete company profile, together with news, charts, recent trade prices, and quite often a message board containing views from other investors.

Also scour the newspaper files for news of any sort about the company you're interested in. The FT's premium-priced 'Level 2' searches provide access to possibly the best background information you can get, because they bring in updates and news from more than 100 news sources. (By the way, you can often get a limited use of this amazing facility for free.) The information exists – you just need to do a bit more legwork with a foreign company than you would with a comparable British one.

Note

Occasionally, you run into a genuine structural mismatch. Some eastern economies measure their progress in terms of gross national product (or national production), instead of gross domestic product as in Britain. Their employment statistics may be based on different parameters, their idea of inflation may be calculated differently, and – in extreme cases – their profit and loss calculations may classify some things differently. Even within Europe, the accounting conventions that apply to various classes of company differ across European boundaries.

Tip

Ignore all these differences. Unless you're looking at a huge deficit in a place where most people expect a surplus, the best approach is to take a deep breath and mutter a prayer to the effect that if those accounts are good enough for the country's own stock market analysts, they're probably good enough for you. Trying to insist on more conformity with the UK than this just frustrates you and serves no point.

Making 25 per cent on the Indian stock market is a waste of time if the rupee falls by 25 per cent against the pound and leaves you right back where you started. Obviously that's an extreme example of currency movements, but you get my point.

Fortunately this argument has an upside as well. If you can anticipate the general trend of a currency's movements over the next few months or years, then you can add to your gains. What's especially gratifying is that often the economies that are on the up have the currencies in demand. That isn't so surprising, really, when you consider that a country experiencing lots of growth attracts other foreigners besides you, all of whom want to buy that currency to gain their stake in the country's future.

But how do you get a handle on which way the currency markets are going? If I knew all the answers to that one, I wouldn't need to work for a living. The shifting currency scene has caught so many investors out over the last 50 years – including some very rich and powerful people – that the consensus view among professionals is that currencies adopt a 'random walk' that's always unpredictable in the short term, but generally pretty reliable in the medium term.

No one can really be certain about these trends, and the cost of getting them wrong can be quite horrendous. But here are a few things that the currency market really, really hates:

A sharply slowing economy, especially if it causes companies in the target country to go bust.

A steep increase in inflation, because inflationary pressures in the future make the fixed-interest returns from government bonds look pretty silly. (I explain this principle in Chapter 6.) In this situation, foreign investors are likely to try to pull out their cash investments, which only makes the situation worse and damages the currency still further.

A weakening interest rate policy, especially when other countries are raising their own bank rates. The only exception is if the markets think that lower interest rates may spark stronger economic growth.

A big foreign trade deficit, especially on top of a heavy foreign debt that may make international investors try to pull out their investment stakes at short notice. A big pull-out of foreign money always hurts a currency.

My own, rather unscientific, view is that although finding a first-world currency moving by more than 10 per cent compared to its historical average against other first-world currencies is common, for those deviations to go beyond 25 per cent is pretty rare.

Which is not to say that it can't happen, however. The pound lost 25 per cent of its value against the dollar between April and November 2008 – which was pretty good going considering that the US economy itself was suffering. But it was an ill wind that brought nobody any good. Anyone in Britain who'd invested in a commodity like gold, that was denominated in dollars, would have made a big profit even though the price of bullion was itself in decline at the time.

Here's another example of how currency movements can work in your favour. A few years ago, I was able to save quite a lot of money off the price of my new German car by buying my euros while the pound was relatively strong and then paying the supplier in euros. If you're buying a house in France or a boat in Italy, the same logic can apply. And the German shares I bought during the trough at the end of 2005 have rewarded me in two ways – first because of their strong growth and secondly because of the beneficial following tailwind they got from the currency markets at a time when the British markets were going nowhere fast.

Tip

Looking outside your own country's shores can be worth the effort.

So let's summarise. If you're willing to go that extra mile (or should that read kilometre?), and if you can locate and research investments that aren't tightly tied to the United Kingdom itself, you can improve your portfolio in three different ways. You can dilute the risk of your overall portfolio by spreading it between a range of economies, some of which will be coming up while others are going down. You can benefit from changes in currency exchange rates that will sometimes be so big that they outweigh any downward movement in those foreign markets – assuming that you're a sterling-based investor, of course – and you can more generally get a feel for the character of an investment world that's becoming more global as time goes by. And which won't ever go back to the way it was 20 years ago.

Are you ready for the challenge? In Chapters 14 and 15 we look at related questions, such as how to read the international environment in the first place, and where to find the information you need.