In This Chapter

Understanding how commodity markets work

Making sense of the statistics

Investing in oil, food, copper – and uranium!

A few years ago, only the very bold, the very skilled, and the slightly unstable ventured into the commodities markets. Their pricing patterns were so hard to forecast (or so some people believed) that they could spell death to any portfolio that was unwise enough to include them.

These days the commodities markets have been tamed to the extent where they can provide a useful counterpoint to the hurly-burly of the stock markets. And the arrival of new investment tools such as Exchange-Traded Funds has made it as easy to invest in copper as in Marks & Spencer.

Companies are familiar, because everyone knows what they do, and pretty well anyone can see what makes a good one different from a bad one. Savings accounts are the same: you can feel reasonably sure that what you see is what you're going to get. You're going to lend somebody your money, and he's going to return it with interest, or some other form of agreed payback.

But you enter a different sort of game when you start working with commodities. Put simply, one pile of iron ore looks very much like another pile of iron ore, and surely only an expert can tell you which one's worth a lot of money and which one's just so much scrap? Since I'm not a geological expert, and probably neither are you, surely you're going to be on your own in the company of thousands of people who actually know what they're doing?

Relax. I'm not going to ask you to pick out the good stuff from the bad. Nor, for the most part, am I going to ask you to choose the companies that produce the best commodities. Instead, I'm going to ask you to believe me when I say that there are very reliable grading systems for minerals and foodstuffs and so on – and that unless you're really determined to hand-pick your own mining companies, you can safely ignore the worry that you're buying a pup.

That's because the commodities market would be nothing without its system of product standardisation. If I phone a corn dealer in Australia with an order for 20,000 tonnes of wheat, I don't want to go and see it in person – although I suppose I might want to see the certification that it's good stuff with not too many nasties. And he for his part knows that if he ships me a consignment of poor-quality goods we both end up in court, so he has no incentive to lie to me.

The same principle goes for coal or oil or copper or gold. The business world works on the assumption that one pile of copper is the same as any other pile that carries the same quality classification. And one gold ingot from Australia is worth the same as a similar ingot from South Africa, providing that it's properly certified. The commodity business is commoditised. That's what enables someone like me to invest in raw commodities even though I don't know much about the technicalities of the industry.

A lot of the time, I never see the product at all – instead, I just take a gamble in the industry by buying some sort of 'tracker' investment that follows the prices of oil or coal or gold, or whatever. Chapter 14 covers the growing popularity of Exchange-Traded Funds, which are just like trackers except that you can buy and sell them on the spur of the moment exactly like shares. And these ETFs are springing up all over the place, in London and elsewhere, allowing you to 'buy into' the price of a commodity and then sell it out when you've made a profit on it. ETFs are clever things.

What's an ETF? In its simplest terms, it's a kind of tracker fund that will enable an ordinary investor like you or me to 'take a stake' in some large and intangible investment like gold or oil or Chinese shares, without necessarily knowing anything about the ins and outs of that market. ETFs are a major advance for people who like to follow their noses and their instincts.

ETFs aren't shares, strictly speaking, but they behave exactly like shares or investment trusts because you can buy them from your stockbroker like a share, in any quantity you like – for instance, there's no other way that you could buy £500 worth of oil (as distinct from oil producing companies)! You can then sell your ETFs whenever you're ready, exactly as if they were shares, and you'll find that you get a sale price that's very close to the buy price that you'd been the buyer. (The City would say that the 'spread' is very small.) Best of all, you don't pay stamp duty on ETFs!

So, as I hope I've made clear, the advent of ETFs just about does away with the idea that pure commodity trading (as distinct from buying commodity producers) is only for the professionals. Until ETFs were launched a few years ago, the idea that the only people able to trade effectively in commodities were those able to lay down hundreds of thousands of pounds at a time contained some truth. (And stand around in a bear-pit wearing silly blazers and waving their arms around.) These days, as I've said, anyone can trade in commodities – and frankly, most of us probably should sometimes.

I'd be the first to agree that commodities can be a bit daunting for a beginner, because you're not looking at individual companies but at big macro-economic trends instead. And many non-food commodities do something rather wonderful. They move in long-term price cycles, often lasting a decade or more, which are largely independent of whatever the stock market happens to be doing at the time. And that makes them especially interesting for an investor who's looking to mitigate some of the risks involved in equity investing.

Indeed, some very experienced investors claim that commodity prices habitually rise when share prices are falling. I'm a bit wary of agreeing with that theory myself, because it seems too simplistic and too counter-intuitive to be really likely. All right, I can't deny that the terrific price rises in oil and copper and gold during 2007 and early 2008 were happening at a time when world stock markets were undergoing their worst crisis in a decade. But the stiff price falls that followed as the credit crunch of 2008 got under way do raise some serious questions about just how wise these 'experienced' commodity investors really were?

The professionals spent the second half of the credit crunch trying to convince us that 2008 was an exceptional situation for the commodity, markets. Ordinarily, they said, the commodity producers don't really care whether or not their customers can afford to buy their products. They cost what they cost, and that's that. Like it or lump it.

Well, that argument didn't stand the test of time particularly well, because the market prices of most major commodities fell pretty sharply during late 2008. The traders mostly spent those months trying to defend their idea with the claim that commodity prices were being driven up, and then sharply down, by hedge funds which had taken up vast speculative positions in gold, copper, oil and other minerals, and which had then dumped them all when the credit crunch of 2008 got started. It was all getting a bit much to swallow by the time the end of 2008 approached and the oil price was still down at about a third of what it had been just six months earlier. Ouch!

But even so, the commodity bulls' argument has a kind of logic, at least as far as energy and base metals are concerned. The thing is, building a copper smelter or digging a copper mine costs an awful lot of time and money – and that creates a very dangerous time lag between the supply and the demand. That's where the real tensions in the commodity markets start to kick in. So let me see whether I can explain this very simply.

Suppose you're a big mineral company. By the time you've spotted a rising global demand for copper and dug your mine, or built your brand-new smelter, you're already five years too late and everybody else in the world has been doing the same thing. All of a sudden the world has too many copper smelters and they're all having to sell their copper very cheaply just to keep going. That's when the copper price collapses, the surplus copper smelters get put into mothballs, and the industry goes into a cyclical slump. This isn't anything to do with the state of the stock market at all, is it?

The situation's pretty much the same with forestry products such as timber, cardboard, and paper, except that the commodity cycles last much longer. A tree takes 20 years to grow, and by the time you've planted your forests and waited patiently to fell them, a good chance exists that the wave has passed and nobody wants your wood pulp any more. So you lose interest, and planting slows down or stops, and the next thing you know there isn't enough timber to go round and prices start to soar again.

Or suppose you run a rubber plantation, and you suddenly notice that other people are getting good prices for growing coffee or bananas or coconuts. You dig up your trees, and with a bit of luck you're in business within five years. The trouble is, so's everybody else! The whole commodities world is running on what my dad used to call kangaroo petrol – it's either lurching forward or stuttering and stalling, and because of those time lags no easy way exists of smoothing out the periods in between. Commodity prices are constantly soaring and nose-diving, according to these cyclical patterns. Read the patterns correctly, and you can get rich – in theory, anyway.

But you need to be aware of two big exceptions to this cyclical principle. One is annual food crops. Often a farmer only requires a year to switch from rapeseed to wheat, or from cabbages to soya beans, or even from cattle to pigs. So the commodity cycle here is so short that it's not really a cycle at all. Instead, unpredictable things like floods, droughts, bird flu, and late frosts throw food commodity prices about. All those things mean that food crops are generally far too dangerous for a beginner to get involved in. Unless you can see a big long-term global trend coming up, such as an exploding Chinese demand for imported soya beans, avoid tangling with food commodities.

The other big commodity exception is in the field of gold, gemstones, and precious metals, and they can be just as dangerous for an unlucky amateur investor. You can't build a gold factory or a diamond manufacturing plant, much as you'd like to – instead, the value of these commodities is determined precisely by their scarcity, and by the absolutely limited supply of new gold and diamonds that comes onto the market every year.

This extreme scarcity makes gold and silver and platinum so precious – and so volatile when the rest of the world suddenly decides to buy them! Temporary scares about the dollar make investors rush to pay absurd amounts for bullion. And then, as likely as not, they're able to repent at leisure.

Is gold too expensive? Not if you compare the historical price trends. Back in 1980, worries about rising oil prices and an impending war between Iran and Iraq sent the price above $850 per troy ounce – which doesn't sound so crazy compared with today's prices until you allow for the costs of inflation. In real (inflation-adjusted terms), you'd have to be paying way in excess of $2,500 per ounce before you beat the 1980 price.

To make a success of a commodity portfolio, you need to have a reasonably good grasp of which products are being bought by which parts of the world, and which ones are rising or falling in popularity. In fact that's not as hard as it sounds. Gaining this information is largely a matter of reading the papers and using your common sense. If your Sunday paper tells you that China and India are going full tilt with their manufacturing industries, then you've got a pretty good idea that they're going to be buying all the iron ore and copper and oil they can lay their hands on. If you read that Australia or South America is expecting a bad harvest, you can probably figure out for yourself that wheat prices are likely to be on the rise soon. But conversely, if you hear that big companies in those countries are falling on hard times, or that Japan's export industries are flagging, or that America has just slapped an embargo on Chinese chemical exports, then you can logically expect commodity prices to have a harder time.

This principle is often described as the commodities super-cycle. According to the current theory, the world has always moved between over-production and under-production in great long waves, just the way I've described it. But with an added twist. The huge levels of demand from the developing asian economies – china in particular – means that we have entered a new era with regard to commodity demand, the like of which humanity hasn't seen before.

Essentially, the 'supercycle' theory has it that virtually commodity prices will continue to trend strongly upwards as Chinese and Indian industries keep churning out consumer goods for export, and as the population of the two countries leaves the countryside and heads for the cities. For instance, it's currently estimated that this urbanisation trend is seeing 13 milion people flood into Chinese cities each year – that's the equivalent of creating a new city the size of London each year. With such massive energy and commodity consumption, the super-cycle theory isn't exactly easy to ignore.

So the supercycle theorists reckon that the steep commodity price falls we saw in 2008 don't amount to a hill of beans in comparison with the crushing inevitability of global economic development. Are they right? I don't really know, and nor does anybody else – but it would take a real diehard to suppose that we in the West could argue with three billion people in the developing countries of Asia!

As a general rule, the wider your reading, the better informed you are. If you have the appetite for vast amounts of detailed information, look at the second section of the Financial Times, where the commodities coverage is especially good in the midweek editions. Broadsheets like The Times or the Daily Telegraph do a decent job of reporting the major trends but don't give you the same sort of detail. Also read The Economist for an informed and sensitive analysis of where the overall supply and demand trends are heading, especially on energy matters. No magazine handles the political aspects of trade better.

Tip

Don't get too bogged down in detail, in spite of all that reading. Focus instead on the 'top-down' aspects of the commodities trade (i.e. start by looking at the big 'macro-economic' realities facing the globe) and take your research downward from there. You'd soon start to drown in the small print if you tried to follow every one of the thousands of news threads, most of which are deeply boring!

As you'd expect, there's plenty of good online information out there on the shape, structure and pricing history of the mining industry. Some of it, like the information published by the World Gold Council, is hardly impartial, because it represents the views of a set of interested parties (mainly gold producers and users); other sources, such as Kitco (www.kitco.com), adopt an impartial approach which simply gives you the prices and shows you charts that illustrate the trading patterns of the past.

But as a general guide to the metals industry in particular, I'd like to point you toward a new web site which is currently being put together by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (Unctad), and which will eventually provide information on prices, industrial usage, mining details and a host of other related matters. You'll find it at www.unctad.org/infocomm – you'll need to click the 'English' tab and then select from the 'Metals and Minerals' menu. Worth keeping an eye on.

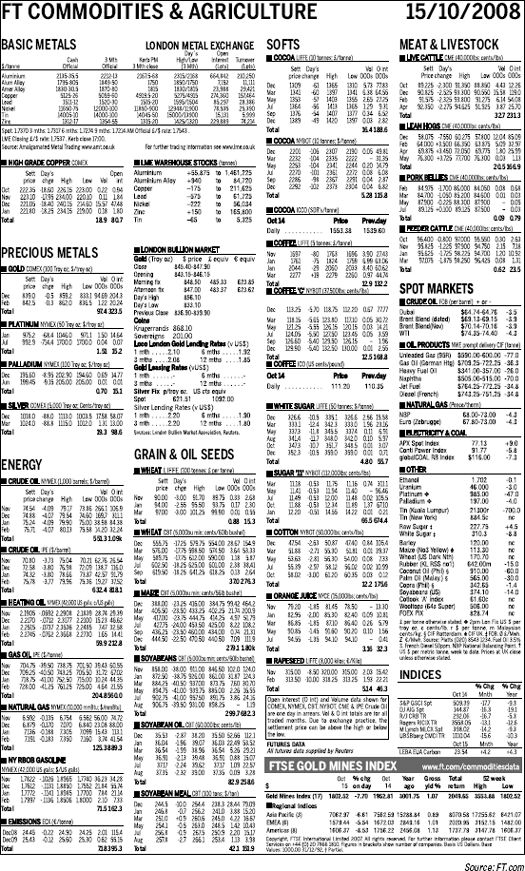

Figure 13-1 shows what's available from the online edition of the Financial Times, practically the only British paper that covers a reasonably broad daily range of the commodities sold on various markets around the world.

I'll admit that this table is bound to look rather daunting to somebody just starting out in investing. And frankly, you're not ever likely to tangle with the commodities industry in the way the people who put this page together imagine. Instead, you're going to want to invest in commodities through ETFs and other types of tracker instruments. But I'm not doing my job if I don't at least give you a glimpse of what the underlying market looks like.

The 'basic metal' prices supplied in Figure 13-1 come from the London Metal Exchange, still the world's foremost authority on the subject. Gold prices come from the London Bullion Market. Oil figures come from the International Petroleum Exchange (also in London); and wheat, white sugar, cocoa, and rapeseed come from the London International Financial Futures Exchange (LIFFE).

But it may not escape your notice that most of the other statistics quoted here are based on data from the North American commodity exchanges: Comex (the New York Mercantile Exchange and Commodities Exchange), Nymex (the New York Metals Exchange), Nybot (the New York Board of Trade), the New York Commodities Exchange, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, and the Chicago Board of Trade. The nearby sidebar, 'Why everything's priced in dollars', explains why America's so dominant in the commodities trade.

One thing you may notice straight away in Figure 13-1 is that the market provides 'cash official' prices, '3 month official' prices, and 'kerb PM 3 month closes' for all the basic metals listed at the top of the page (copper, aluminium, lead, nickel, and the like). This is because heavy and bulky commodities are often bought well ahead of the date they're actually required for delivery, so the market has adapted to allow for this need by providing 'forward pricing'. Manufacturers can't survive without them.

For other sorts of commodities, such as various oil blends, farm products, and meat and livestock, the FT's listings set things out in a different way that provides rather more information. Instead of simply giving you a three-month delivery price for each commodity, in the volumes of goods listed at the top of each sub-table the statistics offer you price data for many months ahead. Grain crops like maize are quoted almost a year ahead! And coffee, orange juice, cotton, and various other commodities are listed even further ahead than that.

On the other hand, Figure 13-1 also gives 'spot market' prices for oil, gas, and energy commodities, plus a handful of miscellaneous farm products. The spot price is the price at which you shake hands on the deal today and sort out the delivery arrangements afterwards. This isn't as sophisticated as having forward prices for a year next month, but it gets the job done.

You can get also get detailed breakdowns of daily commodity prices by looking at Lloyd's List (www.lloydsshipmanager.com), a specialist paper that caters for the international shipping community. Because its readers have so much riding on the state of the commodities scene – and so much more money to make if they can get their ships into the right ports at the right times – the intelligence in Lloyd's List is right up with the very best. You can get a free trial to Lloyd's List, but once that runs out you need to subscribe to get your hands on the data.

Finally, I should mention a company called Platts (www.platts.com), reckoned to be one of the world's most authoritative sources on anything relating to energy. It's pretty good on shipping too! But again, the company charges quite a stiff subscription for accessing the data.

One of my favourite sources of online information on all kinds of commodity contracts is TFC Charts (www.tfc-charts.w2d.com). It isn't going to win any prizes for the attractiveness of its website, but it's reliable, flexible, updated daily – and free.

But equally good, in my view, is the wealth of price information you can obtain from a company called Kitco (www.kitco.com), which supplies data to many of the world's most prominent investment houses. A lot of the time, you'll notice that the Kitco charts are going rather further than simply supplying you with 'spot' information. Instead, you'll find that they give you forward (or futures) prices for a range of different dates in the future. As we noted earlier when we looked at the FT chart, you'll find that these prices might be quite a lot higher or lower than today's 'spot' price. But having them expressed in a chart format rather than just a table of figures is a big help when it comes to getting a picture of the global trend.

The discreet charm of a fast-disappearing asset makes the investment world sit up and take notice. You can hardly open a newspaper these days without somebody telling you that we're living in the age of Peak Oil. They mean that the world's consuming more and more of the stuff, at the exact same time as oil resources are beginning to tail off. And therefore that you can make money by buying into oil stocks now, because oil's never going to get any cheaper and can only get more expensive. Why, you only have to look at the falling levels of new oilfield discoveries to realise that the world's living on borrowed time.

Is that actually true, though? Many people in the oil extraction industry say that, although they're getting less successful at finding new oilfields, they're getting much better at extracting every last drop of oil from the wells that already exist, and that therefore the rate of oil depletion may be a bit slower than the pessimists expect.

Every time the oil price rises, oil experts say, it becomes viable to spend a little more money on giving all the depleted oilfields a thorough work-over. And at the same time, whole new oil extraction possibilities come into view. I'm not just talking about spending money on converting grain into bioethanol; the Canadian Oil Sands project has billions of tonnes of crude locked up in a series of ancient bituminous lakes. As long as crude oil was $40 a barrel, the Oil Sands' fixed extraction costs of around $35 weren't worth bothering with; but now that a barrel frequently fetches $55 and often more, the economics have been transformed.

If you're looking for long-term information on the world's energy situation, you can't do much better than the annual BP Statistical Review of World Energy, available through the BP web-site (www.bp.com). Hundreds of pages of information are available on oil, natural gas, coal, electricity, and so on – both production and consumption – and you can download the data either as a PDF file (for use with Adobe Acrobat), or as an Excel chart if you don't mind not having the very latest information.

Alternatively, a free 80-page download, 'Key World Energy Statistics', is available on the International Energy Agency's website (www.iea.org/Textbase/stats/index.asp), together with a daily oil market report (http://omrpublic.iea.org).

How do you invest in oil? Well, you can buy shares in Shell or BP or any of the other companies that actually produce, process, and distribute the stuff. If you fancy the added excitement of an emerging market situation, a Chinese company like PetroChina (available on the New York Stock Exchange, and listed in US dollars) ought to give your heart that extra tweak when the exchange rate shifts. But that route's full of risks. Instead, the main objective here is to look for 'pure' investments instead. So the main options consist of the following:

Using Exchange-Traded Funds, which behave exactly like shares but track the underlying prices of oil.

Investing directly in government oil funds like the US Oil Fund, which track the oil price and charge a modest management fee.

Buying a UK-based energy trust such as the Investec Global Energy Fund or the ABN AMRO Energy Fund, both of which invest in oil companies but tend to shadow the prices of the raw commodity itself.

Buying oil derivatives with the aim of second-guessing the markets.

I honestly can't recommend the derivatives option, because it's just too tough and too dangerous for a beginner. Not only are you in the company of experts when you trade derivatives – you also run the risk of potentially unlimited losses if your bet goes wrong (take a look at Chapter 12 for more on derivatives).

As for using government oil funds, that's a rather old-fashioned approach for a private investor these days, and it may turn out to be unfeasibly expensive and awkward. Why bother with all that hassle when you can buy a UK-listed ETF that goes straight into your Individual Savings Account (ISA) and gives you tax efficiency too? (ETFs are currently exempted from stamp duty on purchases.)

The nearby sidebar, 'Finding an oil or gas ETF', provides some useful sources.

Note

You can get daily price quotes for all ETFs from the London Stock Exchange, or from your usual stockbroker. If you have a nominee account with an online (execution-only) broker, you should be able to buy, sell, and price any of these without any difficulty at all. See Chapters 2 and 3 for more on dealing with brokers.

Once you've decided what sort of oil you're interested in, laying your hands on the price information you need should get a little easier. You can find a comprehensive range of price information in every kind of online publication (rather fewer from the printed media). The list, in fact, is daunting. But here are a few of my favourites:

I rather like the approach at WTRG Economics, (www.wtrg.com), an American website that contains a pretty good run-down of the major issues facing the oil industry together with some in-depth analysis of the current major news stories.

Can you possibly tell how much more expensive oil is going to be in twelve months' time? No, is the short answer, but you can get a very good feel for how the market regards its own prospects by tuning into the oil futures market.

What's the oil futures market? If you're running a bus company and you're worried that rising diesel prices may put you out of business by Christmas, you can protect yourself by 'hedging' your future diesel requirements. That is, you do one of two things:

You make an agreement with a supplier whereby you pay him an agreed price for the fuel he's going to deliver to you in a year's time. That price is probably higher than the going rate in today's marketplace because the supplier's taking a gamble on the possibility that he may need to sell you the oil for less than he can get for it from somebody else, so you're paying him a bit over the odds to keep him sweet.

You take out a bet on the futures market, whereby you 'win' a lot of money if the oil price rises between now and Christmas. Your winnings compensate you at least partially for the burden of the higher fuel bills that you're paying by then. (In fact, the same principle of using futures for a hedging strategy applies to all types of commodities, from gold right the way through to wheat or even currencies. Unsurprisingly, commodities and futures markets always go together, even in Communist China, which doesn't really approve of them.)

What all this tells you is that, if you can find out what the hedging markets are saying right now, you can figure out whether the market thinks the price is likely to rise or fall. You often find a news report that says something like 'Brent crude for December delivery rose by $3 to $150 per barrel on fears of an escalation of tension between Iran and Israel'.

Whoops, you've just tripped over another hidden wire in the grass. You probably don't need me to tell you that real, physical, and political events can send the oil price all over the place. And no real substitute exists for keeping yourself informed about the global trade economy if you want to play the oil markets effectively.

To explain more, if the slightest chance exists of armed conflict, or sabotage to a pipeline, or even just a political stand-off (reports like 'Moscow today suspended shipments to Western Europe because of disputes over its human rights policy'), it can send the oil price soaring.

Note

The oil industry has seasons! Oil prices commonly dip a bit during the late spring when the central heating systems in the northern hemisphere go off, and then rise again when America's 'driving season' gets under way in May.

Taking a 'pure' investment in oil is very different from investing in the production company that drills it and produces it.

You don't need me to tell you why oil producers' fortunes go up and down at a different rate from the prices of the goods they produce. Having a barrel of oil in a tank and selling it to someone is one thing; having it sitting a mile underground, or perhaps underwater, under a chunk of land that belongs to a foreign government is quite another. The oil companies have to cope with a welter of different risks, from technical issues and transport problems to manpower shortages, environmental issues, and – not least – the sheer political risk of trading in a sensitive commodity under a foreign government's nose, which isn't always easy.

So much for the companies that produce the oil when an exploration company's located it. But the explorers who drill for the stuff in the first place are a different breed altogether. Obviously, the oil majors themselves do a lot of exploration, but a small army of independent explorers also work the oilfields of the world – many of them tiny little outfits with market capitalisations that barely make it into the millions. These independents know that they stand to make big money if they ever hit a really large deposit – which is why so-called 'value investors' and other adventurous types who like to buy risky things at cheap prices love them so much.

Warning

Don't touch independent explorers if you haven't got a higher than average appetite for risk – they have a habit of going bust. That said, more than 90 of them are in the Alternative Investment Market (AIM) listings at the back of the Financial Times or on the London Stock Exchange's website (www.londonstockexchange.co.uk).

Food commodities (often called 'soft commodities') are a bit different from mainstream commodities, for a number of reasons. They don't conform to the usual long-term cycles that dominate the metals industry, say, or the oil industry. That's because for a farmer to switch from coffee to soya (and back again, if need be) takes such a short time that predicting which way things are likely to turn in the next twelve months is incredibly hard.

A frost, drought, or flood will open up the possibilities for big price swings at very short notice. That's why you should never regard food commodities as anything other than a tough gamble, unless you're absolutely cast-iron certain that a particular trend's going to happen over a number of years. And even then, you'll be sharing the bear pit with thousands of dedicated experts, many of whom have their own intelligence operations running in various parts of the world. The big boys use aerial photography to tell them how the crops are coming on in Russia or Brazil – and if you haven't got that information too, you're going to be at a competitive disadvantage!

If that thought doesn't scare you off, then good luck to you. You can always buy shares in a major agribusiness company like America's Bunge, but once again I advise you to use an ETF every time. An ETF is flexible, fast, liquid, and doesn't incur stamp duty. The nearby sidebar, 'Finding a food products ETF', lists the relevant codes.

Before very long you will notice that many of the world's most prominent food ETFs track a series of price indices (see Chapter X on indices) run by the Dow Jones organisation in New York, in collaboration with the American International Group, and usually known as the DJ-AIG indices. This transatlantic predominance is for a reason.

America, and more specifically Chicago, is the spiritual home of all the world's biggest agricultural derivative industries. America's Midwest farming industries first felt the need to have a futures system way back in the nineteenth century, to insulate themselves from unexpected fluctuations in the grain prices and 'hedge' against crop disasters that may wipe out either the farmers or the food merchants, or both. (See Chapter 12 for the lowdown on derivatives.) So, by no particular coincidence, Chicago quickly became the centre for hard-headed folk who understood enough about agricultural risk to create what became the world's premier farm derivatives market. It's still the dominant worldwide centre today.

That's where ETFs come into the picture. ETF providers don't actually buy grain, or oil, or whatever. Instead, they keep some of their money in cash and trade the rest of it in futures contracts and so forth – things that bring them disproportionately large gains or losses according to which way the markets move as time goes on. And those are the gains and losses that get passed back to you in the form of the profits or losses you make on your ETFs.

I'm over-simplifying the situation quite outrageously here, but as a working explanation of a very complicated financial product, I'm at least pointing you in the right direction. ETFs are very tightly regulated, and a welter of protective legislation secures your money, so you've no reason to feel that ETFs are any less secure than ordinary shares.

And so to the gold market, perhaps the most darkly fascinating area of the whole investment scene. Gold's value can soar and then plummet, often within a matter of months (see 'Considering exceptions to the cyclical process', earlier in this chapter), and must make more people unhappy with its long-term performance than almost any form of investment because:

It doesn't pay interest or dividends.

It doesn't have many industrial uses.

It's expensive to store, transport, and insure.

It lost half its value in the early 1980s, and then took 27 years to regain even its nominal value! (Gold was still 60% down on 1980 in real terms at the time of writing.)

The reason gold's value is so unpredictable is simply that a finite amount of the stuff exists, and when everybody decides they want to have some a scramble always takes place for the short available supply.

Gold also has a few industrial uses, despite everything. For example, it's an excellent electrical conductor, which is why many of the chips and memory cards in your personal computer have gold-plated edges. It's used in certain types of electroconductive paint, and it turns up in the devices that scrub the exhaust systems of big industrial plants. Oh, and Japanese restaurants serve it to their customers with the flaked chocolate toppings on their desserts.

But all these applications put together can't make much of a destructive dent in a global market that prizes the indestructibility of gold. Gold doesn't rot, it doesn't rust, and although it's soft it can be melted down and reclaimed easily. Estimates are that 90% of the gold that's ever been mined is still in existence. A sobering thought.

You're going to want to know many things when you buy a gold investment, but perhaps the most obvious is the one you may well miss. Gold's value is the combined result of its scarcity and its ability to make people feel safer when they experience greed or fear – but how exactly are you going to measure that scarcity and make sure that it's still there?

The best information source is the World Gold Council, a private consortium of gold producers around the world that has a vested interest in selling you gold. It publishes regular surveys of the amounts of gold being dug out of the ground, together with the shape and structure of demand from jewellers, manufacturers, and of course the central banks who like to keep gold as a reserve currency. You need a free subscription to read the online reports, but logging on to www.gold.org is worthwhile if you're at all serious about gold investing.

Gold mining production has been falling well short of global demand during the last five years or so, which is why prices have risen so much. Every gold mining company worth its salt has been digging new mines as fast as it can, but with little likelihood of any of them beginning to produce gold until at least 2010. You must decide for yourself whether that means gold has a secure future, but to me the indicators are looking good so far. Figure 13-2 shows the generally upward price movement for gold since January 2000.

Round-the-clock 'spot' gold prices are quoted in the daily papers and on the Internet. But you may not know that the global price is fixed twice a day in Britain, by the so-called London Gold Pool, whose five members hold a telephone conference at 10.30 a.m. and 3 p.m. Dealers all over the world then use those prices as a benchmark for fixing spot prices. But serious traders can also get 'forward' gold prices, which effectively fix a sale price for some future date and are used in hedging arrangements.

The trouble with gold is that it's so awkward to have around the house. If you buy gold abroad you need to ship it, insure it, and possibly face a lot of wrangles about value added tax (gold is VAT free in the UK, but not in every other country).

Small wonder, then, that investors go out looking for more convenient ways to own gold bullion. One way is through a 'proxy gold' scheme such as the one the government of Western Australia runs. You buy your gold from the Perth Mint (www.perthmint.com.au) and instead of posting it to you, they keep it in a vault and send you a certificate from the government and accredited by the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA), the New York Commodities Exchange (Comex), and the Tokyo Commodities Exchange (Tocom). That's a pretty high level of investor protection. And if you prefer to take physical delivery of your gold, they can arrange that as well.

This still sounds like too much trouble to most people, though. Now that Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs) have become commonplace among commodity investors, you can simply buy one of the many bullion and precious metal ETFs. I use ETFS Gold Bullion and I can buy it and sell it on the spur of the moment through my online ISA account, just like a share. But the Lyxor Gold Bullion Securities ETF is also very popular and very liquid.

Tip

Both of these ETFs are denominated in US dollars, so make some allowance for the possibility of currency movements affecting your returns.

Silver, platinum, palladium, and a host of other precious metals are traded on the commodities markets. The only thing I'm going to say is that, although silver is often regarded as a 'poor man's gold', involving lower-cost transactions than its bigger brother, it doesn't have the same characteristics.

For one thing, rather a lot of silver exists. Almost every mine that produces lead, nickel, or tin has deposits of the stuff mixed in with its seams, as a natural result of the volcanic geology that creates all metal deposits in the first place. This means that the key attribute of gold – its tightly limited availability – simply doesn't apply to silver. There are vast quantities of the metal out there.

That's not quite so bad as it might seem, actually, because silver is used quite a lot in industry. Its good conducting qualities, its chemical sensitivity to light and its ability to withstand extremes of temperature have created a vast number of applications in medicine, in electronics manufacturing, and of course in photography, where it's a basic component of film. It does of course have a major role to play in the jewellery industry, and in coins, cutlery and tableware. But a growing proportion of the world's output – maybe 10% – is now going straight into silver bullion bars for sale to investors whose finances can't quite stretch to gold ingots.

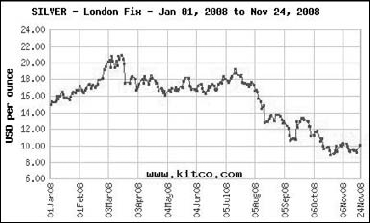

The good news, for an investor, is that the silver price improved massively in the first seven years of the 21st century, rising from just $5.25 at the start of the decade to $10 in November 2008. That's double what you'd have got from either the London stock market or the American S&P 500 index. The bad news is that it has also seen prices as low as $4 and as high as $21 along the way! Figure 13-3 shows you fluctuations in the price of silver during the course of 2008.

Platinum is another ball game entirely, however. On the one hand it's in very limited supply: there are only about ten major producers in the world, and 90% of global production comes from just two countries, Russia and South Africa. On the other hand, it has quite a number of industrial uses, which means that, unlike gold, it tends to get used up.

It might surprise you to know that only about 25% of the world's platinum production goes into jewellery. 5% goes into glass manufacturing, 6% goes into electrical goods, 3% is used in generating energy, and another 5% is bought by the chemicals industry for amalgamation into other products. Perhaps most importantly, more than 50% or the world's platinum production is used to make the catalytic converters that are used in the exhaust systems fitted to nearly every car on the planet. When you think about how many new cars are being sold every year in China or India, it's clear that the prospects for this scarce metal are probably more secure than gold itself.

What's more, it takes a lot more technology to extract platinum from its ore than would normally be the case with gold – a popular estimate is that it takes 12 tonnes of ore to produce a single ounce of gold, and the extraction process may well take six months to complete. What does that mean for investors? It means it's pretty unlikely that new rivals will be able to spring up and contest the dominance of the existing major players. In the City's jargon, the entry barriers are very high.

Palladium, another "rich man's gold", is also finding favour these days among investors who are looking for a rare metal to back. Like platinum, it comes largely from Russia and South Africa (with some also from North America), and like platinum it's used in car exhaust systems, jewellery and electronics. Also in dental applications, where its malleability and adaptability have made it very popular metal. Palladium is the metal that's used in making 'white gold', by melting it in with conventional gold – a process which makes the yellow in the gold fade away.

But if you've been expecting that palladium prices would mirror the soaring cost of gold you're likely to be disappointed. From a price of barely $150 per counce in 1996, the metal soared to nearly $750 in early 2000 – only to fall back steeply to $200 by 2003. Then up to nearly $600 in May 2008, before dropping below $185 as December approached. That's a pretty scary rate of fluctuation, and it should give you all the warning you need not to mess with this most speculative of metals unless your tolerance for risk is exceptionally high. Enough said, I hope.

You don't get a lot of pleasure out of looking at a bar of gold even if you go out and buy one. Gold's inconvenient, hard to insure against loss or theft, and having it lying around the house is a constant worry. Small wonder, then, that most people who buy physical bullion decide to store it in a safe deposit box where it brings them no aesthetic joy at all.

That's just one of the reasons people often prefer to hold their gold in the form of either jewellery or gold coins.

One thing that may well surprise you is how little most sovereigns are worth. Britain has issued so many gold coins over the last century and a half that most of them command only a fairly small premium over the bullion value of the gold they're made from. An inherited gold sovereign in my sock drawer is worth only marginally more than when my father bought it in the 1980s. You can find the same lack of price appreciation happening with South African Krugerrands and Eurozone gold coins. But American gold coins can be worth much, much more because none was issued for a long period, so the scarcity value attached to them is much higher.

Warning

Be prepared to pay some pretty breathtaking commissions when the time comes to sell. The dealer or the auctioneer wants a goodly slice of the action if you're selling through any expert channel (and face it, who in their right mind is going to buy gold from you any other way?). And of course, any dealer who sells you a newly minted gold coin in a presentation box is going to be looking for a so-called 'coin premium' to cover his extra costs. So you need to factor this into your cost calculations. Gold coins are more likely to make your dealer rich than you! But if you're undeterred, do at least think of your gold coin investments as long-term purchases.

My favourite site for bullion and precious metal prices is Kitco (www.kitco.com), which gives up-to-the-moment price information in a range of different formats. The fact that it's US based isn't a problem as long as the world's bullion reserves continue to be valued in US dollars.

Things tend to go awry at weekends, however, because Kitco often switches off its charting updates between Friday night and Monday lunchtime (for Brits) when the US markets finally open. At these times you may get on better with the live-action interactive charts from GalMarley (www.galmarley.com), which are open all hours.

If you're after gold coins and physical bars, your best bet in Britain is probably the country's biggest independent dealer, Chard, which has the rather unappealing-sounding website www.taxfreegold.co.uk. This is an out-and-out sales site, of course, so don't expect impartial advice. But as a general guide to what you're likely to pay for top-quality coins, it's hard to beat.

For every headline that gold, silver, oil, and all the rest of them make, thousands upon thousands of unsung heroes are digging up base metals such as copper, tin, aluminium, and iron ore, and negotiating contracts for millions of tonnes of these indispensable industrial staples. The only time these Plain Janes of the investment world show their faces is when China or India agrees to pay double the price it paid last year for top-grade Australian iron ore.

You can't make high-grade specialist steel out of any old raw materials. Those companies with deposits of the finest mineral grades – and I'm thinking of BHP Billiton, Vale, and Rio Tinto – can virtually command their own prices. That's why the giants of the mining sector are continually on the lookout for new sources of these metals.

Don't forget the stock market power of one of the most toxic metals on earth. As the demand for nuclear energy heats up in the coming decades, so will the need for regular supplies of high-quality uranium deposits.

Uranium ore is actually an amazingly common mineral. Large parts of northern Africa and Australia are strewn with the stuff, and in Europe it turns up in unexpected places: several open-cast uranium mines used to exist in France, although most of them have gone now.

The point is that uranium ore needs an awful lot of processing before you can extract anything you can use in a nuclear reactor. The better the ore quality, the fewer trainloads of rock you need to transport in order to get a kilogram of fuel.

And don't forget the political dimension. Many people are afraid of nuclear power, but now that the oil price seems to have hit higher long-term average levels, the advantages of this energy source are again becoming apparent. Building a new reactor takes eight to ten years, so the physical demand for uranium isn't going to heat up for a long time even if every country in the world starts construction today. But the sheer shortage of suitable ore suppliers in the world has created a nasty bottleneck, which has been doing explosive things to the uranium price.

Good heavens, what a lurching price trend. Between January 2006 and January 2008 you could have quadrupled your money and then lost half of it again. Uranium may be the word on every speculator's lips these days, but it isn't for the faint-hearted.

To locate sources of information on uranium, start with the TFC Charts (http://tfc-charts.w2d.com), and continue through the Kitco base metals site at www.kitcometals.com. And definitely take a look at Infomine (www.infomine.com), which carries charting and price information for nearly 30 different minerals – and in around 50 currencies!