Refactoring. What is it? Why do it?

In brief, refactoring is the gradual improvement of a code base by making small changes that don’t modify a program’s behavior, usually with the help of some kind of automated tool. The goal of refactoring is to remove the accumulated cruft of years of legacy code and produce cleaner code that is easier to maintain, easier to debug, and easier to add new features to.

Technically, refactoring never actually fixes a bug or adds a feature. However, in practice, when refactoring I almost always uncover bugs that need to be fixed and spot opportunities for new features. Often, refactoring changes difficult problems into tractable and even easy ones. Reorganizing code is the first step in improving it.

If you have the sort of personality that makes you begin a new semester, project, or job by thoroughly cleaning up your workspace, desk, or office, you’ll get this immediately. Refactoring helps you keep the old from getting in the way of the new. It doesn’t let you start from a blank page. Instead, it leaves you with a clean, organized workspace where you can find everything you need, and from which you can move forward.

The concept of refactoring originally came from the object-oriented programming community and dates back at least as far as 1990 (William F. Opdyke and Ralph E. Johnson, “Refactoring: An Aid in Designing Application Frameworks and Evolving Object-Oriented Systems,” Proceedings of the Symposium on Object-Oriented Programming Emphasizing Practical Applications [SOOPPA], September 1990, ACM), though likely it was in at least limited use before then. However, the term was popularized by Martin Fowler in 1999 in his book Refactoring (Addison-Wesley, 1999). Since then, numerous IDEs and other tools such as Eclipse, IntelliJ IDEA, and C# Refactory have implemented many of his catalogs of refactorings for languages such as Java and C#, as well as inventing many new ones.

However, it’s not just object-oriented code and object-oriented languages that develop cruft and need to be refactored. In fact, it’s not just programming languages at all. Almost any sufficiently complex system that is developed and maintained over time can benefit from refactoring. The reason is twofold.

Increased knowledge of both the system and the problem domain often reveals details that weren’t apparent to the initial designers. No one ever gets everything right in the first release. You have to see a system in production for a while before some of the problems become apparent.

Over time, functionality increases and new code is written to support this functionality. Even if the original system solved its problem perfectly, the new code written to support new features doesn’t mesh perfectly with the old code. Eventually, you reach a point where the old code base simply cannot support the weight of all the new features you want to add.

When you find yourself with a system that is no longer able to support further developments, you have two choices: You can throw it out and build a new system from scratch, or you can shore up the foundations. In practice, we rarely have the time or budget to create a completely new system just to replace something that already works. It is much more cost-effective to add the struts and supports that the existing system needs before further work. If we can slip these supports in gradually, one at a time, rather than as a big-bang integration, so much the better.

Many sufficiently complex systems with large chunks of code are not object-oriented languages and perhaps are not even programming languages at all. For instance, Scott Ambler and Pramod Sadalage demonstrated how to refactor the SQL databases that support many large applications in Refactoring Databases (Addison-Wesley, 2006).

However, while the back end of a large networked application is often a relational database, the front end is a web site. Thin client GUIs delivered in Firefox or Internet Explorer everywhere are replacing thick client GUIs for all sorts of business applications, such as payroll and lead tracking. Adventurous users at companies such as Sun and Google are going even further and replacing classic desktop applications like word processors and spreadsheets with web apps built out of HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. Finally, the Web and the ubiquity of the web browser have enabled completely new kinds of applications that never existed before, such as eBay, Netflix, PayPal, Google Reader, and Google Maps.

HTML made these applications possible, and it made them faster to develop, but it didn’t make them easy. It didn’t make them simple. It certainly didn’t make them less fundamentally complex. Some of these systems are now on their second, third, or fourth generation—and wouldn’t you know it? Just like any other sufficiently complex, sufficiently long-lived application, these web apps are developing cruft. The new pieces aren’t merging perfectly with the old pieces. Systems are slowing down because the whole structure is just too ungainly. Security is being breached when hackers slip in through the cracks where the new parts meet the old parts. Once again, the choice comes down to throwing out the original application and starting over, or fixing the foundations, but really, there’s no choice. In today’s fast-moving world, nobody can afford to wait for a completely new replacement. The only realistic option is to refactor.

How do you know when it’s time to refactor? What are the smells of bad code that should set your nose to twitching? There are quite a few symptoms, but these are some of the smelliest.

The most obvious symptom is that you do a View Source on the page, and it might as well be written in Greek (unless, of course, you’re working in Greece). Most coders know ugly code when we see it. Ugly code looks ugly. Which would you rather see, Listing 1.1 or Listing 1.2? I don’t think I have to tell you which is uglier, and which is going to be easier to maintain and update.

Example 1.1. Dirtier Code

<TABLE BORDER="0" CELLPADDING="0" CELLSPACING="0" WIDTH="100%">

<TR><TD WIDTH="70"> <A HREF="http://www.example.com/" TARGET=

"_blank"

>

<IMG SRC="/images/logo-footer.gif"

HSPACE = 5 VSPACE="0" BORDER="0"></A></TD>

<td class="footer" VALIGN="top"> ©2007 <A HREF="http://

www.example.com/" TARGET="_blank">Example Inc.</A>.

All rights reserved.<br>

<A HREF="http://www.example.com/legal/index.html"

TARGET="_blank">Legal Notice</A> -

<A HREF="http://www.example.com/legal/privacy.htm"

TARGET="_blank">Privacy Policy</A> - <A HREF="http://www.example.com/

legal/permissions.html"

TARGET="_blank">

Permissions</A>

</td>

</TR></TABLE>Example 1.2. Cleaner Code

<div id='footer'>

<a href="http://www.example.com/">

<img src="/images/logo-footer.gif" alt="Example Inc."

width='70' height='41' />

</a>

<ul>

<li>© 2007 <a href="http://www.example.com/">Example Inc.</a>.

All rights reserved.</li>

<li><a href="http://www.example.com/legal/index.html">

Legal Notice

</a></li>

<li><a href="http://www.example.com/legal/privacy.htm">

Privacy Policy

</a></li>

<li><a href="http://www.example.com/legal/permissions.html">

Permissions

</a></li>

</ul>

</div>Now, you may object that in Listing 1.2 I haven’t merely reformatted the code. I’ve also changed it. For instance, a table has turned into a div and a list, and some hyphens have been removed. However, Listing 1.2 is actually much closer to the meaning of the content than Listing 1.1. Listing 1.2 may here be assumed to use an external CSS stylesheet to supply all the formatting details I removed from Listing 1.1. As you’ll see, that’s going to be one of the major techniques you use to refactor pages and clean up documents.

I’ve also thrown away the TARGET="_blank" attributes that open links in new windows or tabs. This is usually not what the user wants, and it’s rarely a good idea. Let the user use the back button and history list if necessary, but otherwise open most links in the same window. If users want to open a link in a new window, they can easily do so from the context menu, but the choice is now theirs. Sometimes half the cleanup process consists of no more than removing pieces that shouldn’t have been there in the first place.

Line Length

Listing 1.2 is still a little less than ideal. I’m a bit constrained by the need to fit code within the margins of this printed page. In real source code, I could fit a little more onto one line. However, don’t take this to extremes. More than 80 or so characters per line becomes hard to read and is itself a minor code smell.

A small exception can be made here for code generated out of a content management system (CMS) of some kind. In this case, the code you see with View Source is not really the source code. It’s more of a compiled machine format. In this case, it’s the input to the CMS that should look good and appear legible.

Nonetheless, it’s still better if tools such as CMSs and web editors generate clean, well-formed code. Surprisingly often, you’ll find that the code the tool generates is a start, not an end. You may want to add stylesheets, scripts, and other things to the code after the tool is through with it. In this case, you’ll have to deal with the raw markup, and it’s a lot easier to do that when it’s clean.

Usability on the Web has improved in the past few years, but not nearly as much as it can or should. All but the best sites can benefit by refocusing more on the readers and less on the writers and the designers. A few simple changes aimed at improving usability—such as increasing the font size (or not specifying it at all) or combining form fields—can have disproportionately great returns in productivity. This is especially important for intranet sites, and any site that is attempting to sell to consumers.

If any major browser takes more than half a second to display a page, you have a problem. This one can be a little hard to judge, because many slow pages are caused by network latency or overloaded databases and HTTP servers. These are problems, too, though they are ones you usually cannot fix by changing the HTML. However, if a page saved on a local file system takes more than half a second to render in the web browser, you need to refactor it to improve that time.

Pages do not need to look identical in different browsers. However, all content and functionality should be accessible to everyone using any reasonably current browser. If the page is illegible or nonfunctional in Safari, Opera, Internet Explorer, or Firefox, you have a problem. For instance, you may see the page starting with a full-screen-width sidebar, followed by the content pane. Alternatively, the sidebar may show up below the content rather than above it. This usually means the page looks perfectly fine in the author’s browser. However, she did not bother to check it in the one you’re using. Be sure to check your pages in all the major browsers.

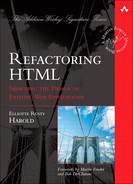

Anytime you see something like “Best Viewed with Internet Explorer,” you have a code smell, and refactoring is called for. Anytime you see something like Figure 1.1, you have a huge code smell—and one that all your readers can smell, too. Internet Explorer has less than 80% market share, and that’s dropping fast. In fact, even that is probably vastly overestimated because most spiders and bots falsely identify themselves as IE, and they account for a disproportionate number of hits. Mac OS X and Linux users don’t even have an option to choose Internet Explorer. The days when you could design your site for just one browser are over.

A common variant of this is requiring a particular screen size—for instance, “This page is best viewed with a screen resolution of 1024 × 768. To change your monitor/display resolution, go to. . . .” Well-designed web pages do not require any particular screen size or browser.

Many sites require cookies, JavaScript, Flash, PDF, Java, or other non-HTML technologies. Although all of these have their place, they are vastly overused on the Web. They are not nearly as interoperable or reliable in the wild as most web designers think. They are all the subject of frequent security notices telling users to turn them off in one browser or another to avoid the crack of the week. They are often unsupported by Google and most other search engine robots. Consequently, you should strive to make sure that most pages on your site function properly even if these technologies are unavailable.

Fortunately, the code smells here are really obvious and really easy to detect. Anytime you see a notice such as this, you have a problem:

Cookies Required Sorry, you must accept cookies to access this site. In order to proceed on this site, you must enable cookies on your Internet browser. We use cookies to tailor our website to your needs, to deliver a better, more personalized service, and to remember certain choices you've made so you don't have to re-enter them.

Not only is this annoying to users, but these sites are routinely locked out of Google and get hideous search engine placement.

Embarrassingly, this next example actually comes from a page that’s talking about cleaning up HTML:

Notice: There is a Table of Contents, but it is dynamically generated. Please enable JavaScript to see it.

The right way to do dynamic content is to use server-side templating, but still sending static HTML to the client.

One site I found managed to hit almost all of these:

This site uses JavaScript, Cookies, Flash, Pop-up windows, and is designed for use with the latest versions of Internet Explorer, Netscape Navigator (NOT Netscape 6), and Opera.

If only they had asked for a specific screen size, they would have hit the superfecta.

This site also added a new one. I had forgotten about pop-ups. Given the rampant abuse of pop-ups and the consequent wide deployment of pop-up blockers, no legitimate site should rely on them.

Of course, some things you can only do with JavaScript or other non-HTML technologies. I don’t intend to tell you not to design the next Google Maps or YouTube, if that is indeed what you’re trying to do. Just try to keep the fancy tricks to a minimum, and make sure everything you can do without Java/JavaScript/Flash/and so on is done without those technologies. This Flickr message is a lot less troublesome:

To take full advantage of Flickr, you should use a JavaScript-enabled browser and install the latest version of the Macromedia Flash Player.

The key difference is that I saw this on a page that still managed to show me the content I’d come to see, despite disabling JavaScript and Flash. I may not see everything, or have full functionality, but I’m not locked out. This is much friendlier to the reader and to search engines such as Google.

As a site developer, I’d still take a second look at this page to see if I might be able to remove some of the requirements on clients. However, it wouldn’t be my first priority.

Web-site defacements are a major wake-up call, and one that gets everybody’s attention really quick. This can happen for a number of reasons, but by far the most common is a code injection attack directed at a poorly designed form processing script.

Frankly, if all that happens is that your web site is defaced, you’re lucky and you should thank the hackers who pointed this out to you. More serious attacks can steal confidential data or erase critical information.

Search engine optimization is a major driver for web-site refactoring. Search engines value text over images and early text over later text. They don’t understand table layouts, and they don’t much care for cookies or JavaScript. However, they do love unique titles and maybe even meta tags.

This is one of the absolute best ways to find out you have a problem. For example, I recently received this e-mail from one of my readers:

The links in the "Further Reading" section of Cafe au Lait to "The Next Big Language?" and "Testing HopStop" are broken. Best regards, Kent

That was a bit of a surprise because the section Kent was complaining about was automatically generated using XSLT that transformed an Atom feed from another site. I checked the feed and it was correct. However, Kent was right and the link was broken. I eventually tracked it down to a bug in the XSLT stylesheet. It was reading an element that was usually but not always the same as the link, rather than the element that was indeed the link. Five minutes later, the site was fixed.

Ninety-nine percent of your readers will just grumble and never tell you that your site is broken. The 1% who do complain are gold. You need to treat them well and listen to what they say. Do not make it hard for them to find you. Every site and almost every page should have an obvious person to contact for any problems that arise. These responses need to be carefully considered and acted on quickly.

Readers may also send you e-mail about many things not directly related to the site: canceled orders, shipping dates, link requests, political disagreements, and a thousand other things. You need to be able to separate the technical problems from the nontechnical ones so that the correspondence can be routed appropriately. Some sites use an online form and ask readers to self-classify the problem. However, this is unreliable because readers don’t usually think of the site in the same way the developers do. For example, if a customer can’t enter a nine-digit ZIP Code with a hyphen into your shipping address form, you may think of that as a technical mistake (and you’d be right), but the customer is likely to classify it as a shipping problem and direct it to a department that won’t even understand the question, much less know what to do about it. You may need a triage person or team that identifies each piece of e-mail and decides who in your organization is the right person to respond to it. This is a critical function that should not be outsourced to the lowest bidder.

Whatever you do, do not let problem reports drop into the black hole of customer service. Make sure that the people who have the power to fix the problems receive feedback directly from the users of the site, and that they pay attention to it. Too many sites use e-mail and contact forms to prevent users from reaching them and firewall developers off from actual users. Do not fall into this trap. Web sites pay a lot of money to hire QA teams. If people volunteer to do this for you, love them for it and take advantage of them.

When should you refactor? When do you say the time has come to put new features on hold while you clean up and get a handle on your legacy code? There are several possible answers to this question, and they are not mutually exclusive.

The first time to refactor is before any redesign. If your site is undergoing a major redevelopment, the first thing you need to do is get its content under control. The first benefit to refactoring at this point is simply that you will create a much more stable base on which to implement the new design. A well-formed, well-organized page is much easier to reformat.

The second reason to refactor before redesigning is that the process of refactoring will help to familiarize developers with the site. You’ll see where the pages are, how they fit together in the site hierarchy, which elements are common across pages, and so forth. You’ll also likely discover new ideas for the redesign that you haven’t had before. Don’t implement them yet, but do write them down (better yet, add them to the issue tracker) so that you can implement them later, after the refactoring is done. Refactoring is a very important tool for bringing developers up to speed on a site. If it’s a site they’ve never previously worked on, refactoring will help teach them about it. If it’s a site they’ve been working on for the past ten years, refactoring will remind them of things they have forgotten. In either case, refactoring helps to make developers comfortable with the site.

Perhaps the new functions are on completely new pages, maybe even a completely new site. If there’s still some connection to the old site, you’ll want to look at it to see what you can borrow or reuse. Styles, graphics, scripts, and templates may be candidates for reuse. Indeed, doing so may help you keep a consistent look and feel between the old parts and the new parts of the site. However, if the old parts that you want to reuse have any problems, you’ll need to clean them up first. For similar reasons, you should consider refactoring before any major new project that builds on top of the old one. For example, if you’re going to implement one-click shopping, make sure the old shopping cart makes sense first. If the legal department is making you add small print at the bottom of every page, find out whether each page has a consistent footer into which you can easily insert it. You don’t have to refactor everything, but do make those changes that will help you more easily integrate the new content into your site.

Finally, you may wish to consider semicontinuous refactoring. If you find a problem that’s bothering you, don’t wait for an uninterrupted two-week block during which you can refactor everything. Figure out what you can do to fix that problem right away, even if you don’t fix everything else. To the extent possible, try to use agile development practices. Code a little, test a little, refactor a little. Repeat. Although many projects will be starting from a large base of crufty legacy code, if you do have a green-field project try not to let it turn into a large base of crufty code in the first place. When you see yourself repeating the same code, extract it into external templates or stylesheets. When you notice that one of your hired HTML guns has been inserting deprecated elements, replace them with CSS (and take the opportunity to educate the hired gun about why you’re doing that). A stream of many small but significant changes can have great effect over time.

Whatever you do, don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good. If you only have time to do a little necessary refactoring right now, do a little. You can always do more later. Huge redesigns are splashy and impressive, but they aren’t nearly as important as the small and gradual improvements that build up over time. Make it your goal to leave the code in better shape at the end of the day than at the beginning. Do this over a period of months, and sooner than you know it, you’ll have a clean code base that you’ll be proud to show off.

There is one critical difference between refactoring in a programming language such as Java and refactoring in a markup language such as HTML. Compared to HTML, Java really hasn’t changed all that much. C++ has changed even less, and C hardly at all. A program written in Java 1.0 still runs pretty much the same as a program written in Java 6. A lot of features have been added to the language, but it has remained more or less the same.

By contrast, HTML and associated technologies have evolved much faster over the same time frame. Today’s HTML is really not the same language as the HTML of 1995. Keywords have been removed. New ones have been added. Syntax and parsing algorithms have changed. Although a modern browser such as Firefox or Internet Explorer 7 can usually make some sense out of an old-fashioned page, you may discover that a lot of things don’t work quite right. Furthermore, entirely new components such as CSS and ECMAScript have been added to the stew that a browser must consume.

Most of the refactorings in this book are going to focus on upgrading sites to web standards, specifically:

XHTML

CSS

REST

They are going to help you move away from

Tag soup

Presentation-based markup

Stateful applications

These are not binary choices or all-or-nothing decisions. You can often improve the characteristics of your sites along these three axes without going all the way to one extreme. An important characteristic of refactoring is that it’s linear. Small changes generate small improvements. You do not need to do everything at once. You can implement well-formed XHTML before you implement valid XHTML. You can implement valid XHTML before you move to CSS. You can have a fully valid CSS-laid-out site before you consider what’s required to eliminate sessions and session cookies.

Nor do you have to implement these changes in this order. You can pick and choose the refactorings from the catalog that bring the most benefit to your applications. You may not require XHTML, but you may desperately need CSS. You may want to move your application architecture to REST for increased performance but not care much about converting the documents to XHTML. Ultimately, the decision rests with you. This book presents the choices and options so that you can weigh the costs and benefits for yourself.

It is certainly possible to build web applications using tag-soup table-based layout, image maps, and cookies. However, it’s not possible to scale those applications, at least not without a disproportionate investment in time and resources that most of us can’t afford. Growth both horizontally (more users) and vertically (more features) requires a stronger foundation. This is what XHTML, CSS, and REST provide.

XHTML is simply an XML-ized version of HTML. Whereas HTML is at least theoretically built on top of SGML, XHTML is built on top of XML. XML is a much simpler, clearer spec than SGML. Therefore, XHTML is a simpler, clearer version of HTML. However, like a gun, a lot depends on whether you’re facing its front or rear end.

XHTML makes life harder for document authors in exchange for making life easier for document consumers. Whereas HTML is forgiving, XHTML is not. In HTML, nothing too serious happens if you omit an end-tag or leave off a quote here or there. Some extra text may be marked in boldface or be improperly indented. At worst, a few words here or there may vanish. However, most of the page will still display. This forgiving nature gives HTML a very shallow learning curve. Although you can make mistakes when writing HTML, nothing horrible happens to you if you do.

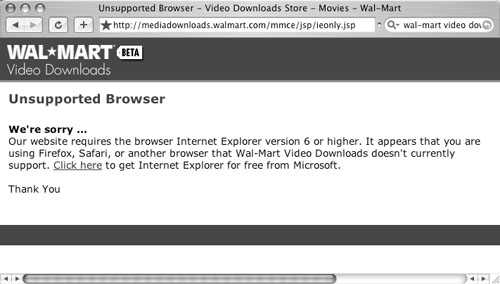

By contrast, XHTML is much stricter. A trivial mistake such as a missing quote or an omitted end-tag that a browser would silently recover from in HTML becomes a four-alarm, drop-everything, sirens-blaring emergency in XHTML. One little, tiny error in an XHTML document, and the browser will throw up its hands and refuse to display the page, as shown in Figure 1.2. This makes writing XHTML pages harder, especially if you’re using a plain text editor. Like writing a computer program, one syntax error breaks everything. There is no leeway and no margin for error.

Why, then, would anybody choose XHTML? Because the same characteristics that make authoring XHTML a challenge (draconian error handling) make consuming XHTML a walk in the park. Work has been shifted from the browser to the author. A web browser (or anything else that reads the page) doesn’t have to try to make sense out of a confusing mess of tag soup and guess what the page really meant to say. If the page is unclear in any way, the browser is allowed, in fact required, to throw up its hands and refuse to process it. This makes the browser’s job much simpler. A large portion of today’s browsers devote a large chunk of their HTML parsing code simply to correcting errors in pages. With XHTML they don’t have to do that.

Of course, most of us are not browser vendors and are never going to write a browser. What do we gain from XHTML and its draconian error handling? There are several benefits. First of all, though most of us will never write a browser, many of us do write programs that consume web pages. These can be mashups, web spiders, blog aggregators, search engines, authoring tools, and a dozen other things that all need to read web pages. These programs are much easier to write when the data you’re processing is XHTML rather than HTML.

Of course, many people working on the Web and most people authoring for the Web are not classic programmers and are not going to write a web spider or a blog aggregator. However, there are two things they are very likely to write: JavaScript and stylesheets. By number, these are by far the most common kinds of programs that read web pages. Every JavaScript program embedded in a web page itself reads the web page. Every CSS stylesheet (though perhaps not a program in the traditional sense of the word) also reads the web page. JavaScript and CSS are much easier to write and debug when the pages they operate on are XHTML rather than HTML. In fact, the extra cost of making a page valid XHTML is more than paid back by the time you save debugging your JavaScript and CSS.

While fixing XHTML errors is annoying and takes some time, it’s a fairly straightforward process and not all that hard to do. A validator will list the errors. Then you go through the list and fix each one. In fact, errors at this level are fairly predictable and can often be fixed automatically, as we’ll see in Chapters 3 and 4. You usually don’t need to fix each problem by hand. Repairing XHTML can take a little time, but the amount of time is predictable. It doesn’t become the sort of indefinite time sink you encounter when debugging cross-browser JavaScript or CSS interactions with ill-formed HTML.

Writing correct XHTML is only even mildly challenging when hand authoring in a text editor. If tools generate your markup, XHTML becomes a no-brainer. Good WYSIWYG HTML editors such as Dreamweaver 8 can (and should) be configured to produce valid XHTML by default. Markup level editors such as BBEdit can also be set to use XHTML rules, though authors will need to be a little more careful here. Many have options to check a document for XHTML validity and can even automatically correct any errors with the click of a button. Make sure you have turned on the necessary preference in your editor of choice. Similarly good CMSs, Wikis, and blog engines can all be told to generate XHTML. If your authoring tool does not support XHTML, by all means get a better tool. In the 21st century, there’s no excuse for an HTML editor or web publishing system not to support XHTML.

If your site is using a hand-grown templating system, you may have a little more work to do; and you’ll see exactly what you need to do in Chapters 3 and 4. Although the process here is a little more manual, once you’ve made the changes, valid XHTML falls out automatically. Authors entering content through databases or web forms may not need to change their workflow at all, especially if they’re already entering data in a non-HTML format such as markdown or wikitext. The system can make the transition to XHTML transparent and painless.

The second reason to prefer XHTML over HTML is cross-browser compatibility. In practice, XHTML is much more consistent in today’s browsers than HTML. This is especially true for complex pages that make heavy use of CSS for styling or JavaScript for behavior. Although browsers can fix markup mistakes in classic HTML, they don’t always fix them the same way. Two browsers can read the same page and produce very different internal models of it. This makes writing one stylesheet or script that works across browsers a challenge. By contrast, XHTML doesn’t leave nearly so much to browser interpretation. There’s less room for browser flakiness. Although it’s certainly true that browsers differ in their level of support for all of CSS, and that their JavaScript dialects and internal DOMs are not fully compatible, moving to XHTML does remove at least one major cause of cross-browser issues. It’s not a complete solution, but it does fix a lot.

The third reason to prefer XHTML over HTML is to enable you to incorporate new technologies in your pages in the future. For reasons already elaborated upon, XHTML is a much stronger platform to build on. HTML is great for displaying text and pictures, and it’s not bad for simple forms. However, beyond that the browser becomes primarily a host for other technologies such as Flash, Java, and AJAX. There are many things the browser cannot easily do, such as math and music notation. There are other things that are much harder to do than they should be, such as alerting the user when he types an incorrect value in a form field.

Technologies exist to improve this, and more are under development. These include MathML for equations, MusicXML for scores, Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) for animated pictures, XForms for very powerful client-side applications, and more. All of these start from the foundation of XHTML. None of them operates properly with classic HTML. Refactoring your pages into XHTML will enable you to take advantage of these and other exciting new technologies going forward. In some cases, they’ll let you do things you can’t already do. In other cases, they’ll let you do things you are doing now, but much more quickly and cheaply. Either way, they’re well worth the cost of refactoring to XHTML.

The separation of presentation from content is one of the fundamental design principles of HTML. Separating presentation from content allows you to serve the same text to different clients and let them decide how to format it in the way that best suits their needs. A cell phone browser doesn’t have the same capabilities as a desktop browser such as Firefox. Indeed, a browser may not display content visually at all. For instance, it may read the document to the user.

Consequently, the HTML should focus on what the document means rather than on what it looks like. Most important, this style of authoring respects users’ preferences. A reader can choose the fonts and colors that suit her rather than relying on the page’s default. One size does not fit all. What is easily readable by a 30-year-old airline pilot with 20/20 vision may be illegible to an 85-year-old grandmother. A beautiful red and green design may be incomprehensible to a color-blind user. And a carefully arranged table layout may be a confusing mishmash of random words to a driver listening to a page on his cell phone while speeding down the Garden State Parkway.

Thus, in HTML, you don’t say that “Why CSS” a few paragraphs up should be formatted in 11-point Arial bold, left-aligned. Instead, you say that it is an H2 header. At least you did, until Netscape came along and invented the font tag and a dozen other new presentational elements that people immediately began to use. The W3C responded with CSS, but the damage had been done. Web pages everywhere were created with a confusing mix of font, frame, marquee, and other presentational elements. Semantic elements such as blockquote, table, img, and ul were subverted to support layout goals. To be honest, this never really worked all that well, but for a long time it was the best we had.

That is no longer true. Today’s CSS enables not just the same, but better layouts and presentations than one can achieve using hacks such as frames, spacer GIFs, and text wrapped up inside images. The CSS layouts are not only prettier, but they are leaner, more efficient, and more accessible. They cause pages to load faster and display better. With some effort, they can produce pages that work better in a wide variety of browsers on multiple platforms.

Shifting the markup out of the page and into a separate stylesheet allows us to start with a simple page that is at least legible to all readers, even those with ten-year-old browsers. We can then apply beautiful effects to these pages that improve the experience for users who are ready to handle them. However, no one is left out completely. Pages degrade gracefully.

Shifting the markup out of the page also has benefits for the developers. First of all, it allows different people with different skills to work on what they’re best at. Writers can write words in a row without worrying about how everything will be formatted. Designers can organize and reorganize a page without touching the writers’ words. Programmers can write scripts that add activity to the page without interfering with the appearance. CSS allows everyone to do what they are best at without stepping on each other’s toes.

Whereas CSS is a boon to writers and designers, it’s a godsend to developers. From a programmer’s perspective, a page is much, much simpler when all the layout and style information is pulled out and extracted into a separate CSS stylesheet. The document tree has fewer elements in it and isn’t nested as deeply. This makes it much easier to write scripts that interact with the page.

Finally, the biggest winners are the overworked webmasters who manage the entire site. Moving the markup out of the pages and into separate stylesheets allows them to combine common styles and maintain a consistent look and feel across the entire site. Changing the default font from Arial to Helvetica no longer requires editing thousands of HTML documents. It can now be a one-line fix in a single stylesheet file.

CSS enables web developers, webmasters, and web designers to follow the DRY principle: Don’t Repeat Yourself. By combining common rules into single, reusable files, they make maintenance, updates, and editing far simpler. Even the end-users benefit because they load the style rules for a site only once rather than with every page. The smaller pages load faster and display quicker. Everyone wins.

Finally, let’s not neglect the importance of CSS for our network managers and accountants. There may be only a kilobyte or two of purely presentational information in each page. However, summed over thousands of pages and millions of users, those kilobytes add up. You get real bandwidth savings by loading the styles only once instead of with every page. When ESPN switched to CSS markup it saved about two terabytes of data a day. At that level, this translates into real cost savings that you can measure on the bottom line. Now, admittedly, most of us are not ESPN and can only dream of having two terabytes of daily traffic in the first place, much less two terabytes of daily traffic that we can save. Nonetheless, if you are experiencing overloaded pipes or are unexpectedly promoted to the front page of Digg, moving your style into external CSS stylesheets can help you handle that.

Representational State Transfer (REST) is the oldest and yet least familiar of the three refactoring goals I present here. Although I’ll mostly focus on HTML in this book, one can’t ignore the protocol by which HTML travels. That protocol is HTTP, and REST is the architecture of HTTP.

Understanding HTTP and REST has important consequences for how you design web applications. Anytime you place a form in a page, or use AJAX to send data back and forth to a JavaScript program, you’re using HTTP. Use HTTP correctly and you’ll develop robust, secure, scalable applications. Use it incorrectly and the best you can hope for is a marginally functional system. The worst that can happen, however, is pretty bad: a web spider that deletes your entire site, a shopping center that melts down under heavy traffic during the Christmas shopping season, or a site that search engines can’t index and users can’t find.

Although basic static HTML pages are inherently RESTful, most web applications that are more complex are not. In particular, you must consider REST anytime your application involves the following common things:

Forms

User authentication

Cookies

Sessions

State

These are very easy to get wrong, and more applications to this day get them wrong than right. The Web is not a LAN. The techniques that worked for limited client/server systems of a few dozen to a few hundred users do not scale to web systems that must accommodate thousands to millions of users. Client/server architectures based on sessions and persistent connections are simply not possible on the Web. Attempts to recreate them fail at scale, often with disastrous consequences.

REST, as implemented in HTTP, has several key ideas, which are discussed in the following sections.

Tagging distinct resources with distinct URLs enables bookmarking, linking, search engine storage, and painting on billboards. It is much easier to find a resource when you can say, “Go to http://www.example.com/foo/bar” than when you have to say, “Go to http://www.example.com/. Type ‘bar’ into the form field. Then press the foo button.”

Do not be afraid of URLs. Most resources should be identified only by URLs. For example, a customer record should have a URL such as http://example.com/patroninfo/username rather than http://example.com/patroninfo. That is, each customer should have a separate URL that links directly to her record (protected by a password, of course), rather than all your customers sharing a single URL whose content changes depending on the value of some login cookie.

Google can only index pages that are accessed via GET. Users can only bookmark pages that are accessed via GET. Other sites can only link to pages with GET. If you care about raising your site traffic at all, you need to make as much of it as possible accessible via GET.

Web spiders routinely follow links on a page that are accessible via GET, sometimes even when they are told not to. Users type URLs into browser location bars and then edit them to see what happens. Browsers prefetch linked pages. If an operation such as deleting content, agreeing to a contract, or placing an order is performed via GET, some program somewhere is going to do it without asking or consulting an actual user, sometimes with disastrous consequences. Entire sites have disappeared when Google discovered them and began to follow “delete this page” links, all because GET was used instead of POST.

The client and server may each have state, but neither relies on the other side remembering what its state is. All necessary information is transferred in each communication. Statelessness enables scalability through caching and proxy servers. It also enables a server to be easily replaced by a server farm as necessary. There’s no requirement that the same server respond to the same client two times in a row.

Robust, scalable web applications work with HTTP rather than against it. RESTful applications can do everything that more familiar client/server applications do, and they can do it at scale. However, implementing this may require some of the largest changes to your systems. Nonetheless, if you’re experiencing scalability problems, these can be among the most critical refactorings to make.

It is not uncommon for people ranging from the CEO to managers to HTML grunts to object to the concept of refactoring. The concern is expressed in many ways, but it usually amounts to this:

We don’t have the time to waste on cleaning up the code. We have to get this feature implemented now!

There are two possible responses to this comment. The first is that refactoring saves time in the long run. The second is that you have more time than you think you do. Both are true.

Refactoring saves time in the long run, and often in the short run, because clean code is easier to fix and easier to maintain. It is easier to build on bedrock than quicksand. It is much easier to find bugs in clean code than in opaque code. In fact, when the source of a bug doesn’t jump out at me, I usually begin to refactor until it does. The process of refactoring changes both the code itself and my view of the code. Refactoring can move my eyes into new places and allow me to see old code in ways I didn’t see it before.

Of course, for maximum time savings, it’s important to automate as much of the refactoring as possible. This is why I’m going to emphasize tools such as Tidy and TagSoup, as well as simple, regular-expression-based solutions. Although some refactorings require significant human effort—converting a site from tables to CSS layouts, for example—many others can be done with the click of a button—converting a static page to well-formed XHTML, for example. Many refactorings lay somewhere in between.

Less well recognized is that a lot more time is actually available for refactoring than most managers count on their timesheets. Writing new code is difficult, and it requires large blocks of uninterrupted time. A typical workday filled with e-mail, phone calls, meetings, smoking breaks, and so on sadly doesn’t offer many long, uninterrupted blocks in which developers can work.

By contrast, refactoring is not hard. It does not require large blocks of uninterrupted time. Sixty minutes of refactoring done in six-minute increments at various times during the day has close to the same impact as one 60-minute block of refactoring. Sixty minutes of uninterrupted time is barely enough to even start to code, though, and six-minute blocks are almost worthless for development.

It’s also worth taking developers’ moods into account. The simple truth is that you’re more productive at some times than at other times. Sometimes you can bang out hundreds of lines of code almost as fast as you can type, and other times it’s an effort to force your fingers to the keyboard. Sometimes you’re in the zone, completely focused on the task at hand. Other times you’re distracted by an aching tooth, an upcoming client meeting, and your weekend plans. Coding, design, and other complex tasks don’t work well when you’re distracted, but refactoring isn’t a complex task. It’s an easy task. Refactoring enables you to get something done and move forward, even when you’re operating at significantly reduced efficiency.

Perhaps most important, I find that when I am operating at less than peak efficiency, refactoring enables me to pick up speed and reach the zone. It’s a way to dip a toe into the shallow end of the pool and acclimatize to the temperature before plunging all the way in. Taking on a simple task such as refactoring allows me to mentally move into the zone to work on more challenging, larger problems.

Refactoring is really a classic case of working smarter, not harder. Although that maxim can be a cliché ripe for a Dilbert parody, it really does apply here.