20.1 Introduction

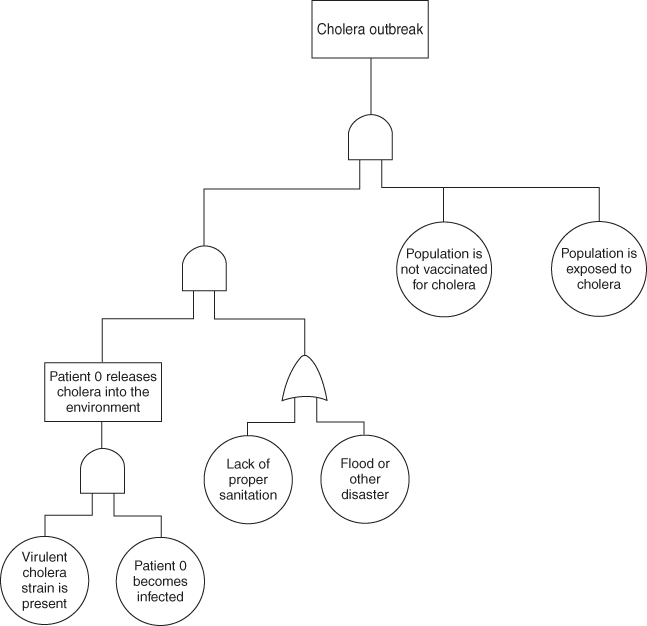

How do we calculate the risk of an epidemic? Over the course of recorded history, there have been thousands, if not tens of thousands, of epidemics. In many African countries, there is a yearly pattern of meningitis that occurs. In some years, there are more districts within a country that are affected and in some years, less, but it appears in recent years that there is a constant threat of a meningitis epidemic (1). Traditional risk assessment models are of little use in calculating the threat of an epidemic. It is possible to use a tool such as fault tree analysis to develop risk scenarios for epidemics, such as Cholera. Figure 20.1 shows how such a tree might appear. It shows that several factors have to come together before an epidemic can occur. It is almost impossible to quantify any of the basic events shown in this model. Epidemic models are used to calculate disease spread through a population, but quantifying the probability that an organism will infect a susceptible person is difficult to impossible (2).

Figure 20.1 Simplified cholera epidemic fault tree.

In reality, there is always a small risk that an endemic disease will erupt, creating an epidemic, and there is really no quantifiable measurement. The best way to think about the potential for epidemics is to consider the potential cause, that is, endemic in nature versus bioterrorism versus susceptible population. There are numerous safeguards in place that protect people from epidemics including vaccinations, early mandatory reporting, isolation of infected individuals, and so on.

Primary Care Physicians (PCPs) take on a variety of responsibilities. They coordinate care between various specialists and they monitor a patient's condition and keep track of a variety of medications. One role that is often overlooked is the role of a PCP in an epidemic. Often the first person to see the “patient zero” in an infectious disease outbreak will be an emergency medicine physician or a family practice physician. It is because of this that in primary care, vigilance and caution must precede any preconceived notions about illness (3).

Sometimes a cold is not a cold. The majority of the time this is the case, but very rarely, more sinister diseases slip through the cracks. Looking solely at the role of the PCP in epidemic situations and at some examples of situations that could occur, things that a PCP should be vigilant on will become apparent.

Surveillance methods have been proposed that utilize general data of normal, expected, common diagnoses at a given time of year and allowed for the appearance of unexpected symptoms at a given time in an unusual distribution to aid in the tracking and identifying of potential epidemics. A study completed in 2001 utilized data pertaining to upper respiratory infections from 1996 to 1999 and outlined the data over the course of 12 months. They were then able to pinpoint outliers during a particular time of year (4). This type of organization of data can allow for the rapid identification of an emerging pattern and aid in the detection of a potential bioterrorist threat.

The PCP serves as a beacon for potential outbreaks and epidemics. There is a set of guidelines, delineated in the article “Recognition of Illness Associated with the Intentional Release of a Biologic Agent” listed on the Center for Disease Control (CDC) web site, for the PCP to follow if they suspect that a reportable disease has walked into their office (5).