Chapter 2. Hello, Rx

This chapter covers

- Working without Rx

- Adding Rx to a project

- Creating your first Rx application

The goal of Rx is to coordinate and orchestrate event-based and asynchronous computations that come from various sources, such as social networks, sensors, UI events, and others. For instance, security cameras around a building, together with movement sensors that trigger when someone might be near the building, send us photos from the closest camera. Rx can also count tweets that contain the names of election candidates to estimate a candidate’s popularity. This is done by calling an external web service in an asynchronous way. For those scenarios and other similar ones, the orchestrations tend to lead to complex programs, and Rx definitely eases that effort, as you’ll see.

In this chapter, you’ll look at an example to see how working with and without Rx makes a difference in how the application is structured, how readable it is, and how easy it is to extend and evolve. Imagine you receive a letter from Mr. Penny, the well-known chief technology officer of the Stocks R Us company. Stocks R Us is a stock-trading company that advises its clients where to invest their money and collect interest from earnings. This is why it’s important to the company to react quickly to changes in the stock market. Recently, Stocks R Us found out that it can save money by using a system that provides alerts about stocks that have experienced—as Mr. Penny calls it—a drastic change. Mr. Penny’s definition of a drastic change is a price change of more than 10%. When these changes happen, Stocks R Us wants to know as fast as possible so it can react by selling or buying the stock.

Mr. Penny comes to you because he knows he can count on you to deliver a high-quality application quickly. Your job (and the target of this chapter) is to create an application that notifies users about stocks that experience a drastic change. A drastic change occurs when the value of the stock increases or decreases by a certain threshold (10% in this case) between two readings. When this happens, you want to notify users by sending a push notification to their mobile phones or displaying an alert on the screen of an application, showing a red flashing bar, for example.

In the first part of the chapter, you’ll explore the steps that usually occur when creating an application with the traditional .NET events approach. We’ll then analyze the solution and discuss its weaknesses.

The second part of this chapter introduces Rx into your application. You’ll first add the libraries to the project and then work step by step to make the application for Stocks R Us in the Rx style.

2.1. Working with traditional .NET events

Stock information comes from a stock-trading source, and many services provide this information. Each has its own API and data formats, and several of those sources are free, such as Yahoo Finance (http://finance.yahoo.com) and Google Finance (www.google.com/finance). For your application, the most important properties are the stock’s quote symbol and price. The stock’s quote symbol is a series of characters that uniquely identifies traded shares or stock (for example, MSFT is the Microsoft stock symbol).

The flowchart in figure 2.1 describes the logical flow of the application.

Figure 2.1. Flowchart of the Stock R Us application logic. We notify the user of drastic change—a change of more than 10% in price.

For each piece of stock information the application receives, it calculates the price difference of the stock as a change ratio between the new price and the previous price. Say you receive an update that the price of MSFT has changed from $50 to $40, a change of 20%. This is considered a drastic change and causes an alert to be shown in the application.

In real life, the ticks arrive at a variable rate. For now, to keep from confusing you, you can assume that the ticks arrive at a constant rate; you’ll deal with time aspects later.

To keep the source of the stock information abstract, it’s exposed through the class StockTicker. The class exposes only an event about a StockTick that’s raised every time new information about a stock is available.

Listing 2.1. StockTicker class

class StockTicker { public event EventHandler<StockTick> StockTick; }

The StockTick class holds the information about the stock, such as its quote symbol and price.

Listing 2.2. StockTick class

class StockTick { public string QuoteSymbol { get; set; } public decimal Price { get; set; } //other properties }

You’ll usually see traditional .NET events in these types of scenarios. When notifications need to be provided to an application, .NET is a standard way of delivering data into an application. To work with the stock ticks, you’ll create a StockMonitor class that will listen to stock changes by hooking up to the StockTick event via the += operator.

Listing 2.3. StockMonitor class

The core of the example is in the OnStockTick method. This is where you’ll check for each stock tick if you already have its previous tick so that you can compare the new price with the old price. For this, you need a container to hold all the information about previous ticks. Because each tick contains the QuoteSymbol, it makes sense to use a dictionary to hold that information, with QuoteSymbol as the key. To hold the information about the previous ticks, you define a new class with the name StockInfo (listing 2.4), and then you can declare the dictionary member in your StockMonitor class (listing 2.5).

Listing 2.4. StockInfo class

class StockInfo { public StockInfo(string symbol, decimal price) { Symbol = symbol; PrevPrice = price; } public string Symbol { get; set; } public decimal PrevPrice { get; set; } }

Every time OnStockTick is called with a new tick, the application needs to check whether an old price has already been saved to the dictionary. You use the TryGetValue method that returns true if the key you’re looking for exists in the dictionary, and then you set the out parameter with the value stored under that key.

Listing 2.5. OnStockTick event handler checking the existence of a stock

Dictionary<string,StockInfo> _stockInfos=new Dictionary<string, StockInfo>(); void OnStockTick(object sender, StockTick stockTick) { StockInfo stockInfo; var quoteSymbol = stockTick.QuoteSymbol; var stockInfoExists = _stockInfos.TryGetValue(quoteSymbol, out stockInfo); ... }

If the stock info exists, you can check the stock’s current and previous prices, as shown in the following listing, to see whether the change was bigger than the threshold defining a drastic change.

Listing 2.6. OnStockTick event handler handling drastic price change

If the stock info isn’t in the dictionary (because this is the first time you got a tick about it), you need to add it to the dictionary with

_stockInfos[quoteSymbol]=new StockInfo(quoteSymbol,stockTick.Price);

When no more updates are required (for example, when the user decides to stop receiving notifications or closes the page), you need to unregister from the event by using the -= operator. But where should you do that? One option is to create a method in the StockMonitor class that you can call when you want to stop. But luckily, .NET provides a mechanism for handling this type of “cleanup” by implementing the IDisposable interface that includes the single method Dispose for freeing resources. This is how it looks in StockMonitor:

public void Dispose()

{

_ticker.StockTick -= OnStockTick;

_stockInfos.Clear();

}

The full code is shown in listing 2.7. I ran it on the following series:

Symbol: "MSFT" Price: 100 Symbol: "INTC" Price: 150 Symbol: "MSFT" Price: 170 Symbol: "MSFT" Price: 195

and I got these results:

Stock:MSFT has changed with 0.7 ratio, Old Price:100 New Price:170 Stock:MSFT has changed with 0.15 ratio, Old Price:170 New Price:195.5

Listing 2.7. StockMonitor full code

Mr. Penny is satisfied, Stock R Us staff is using the application, and the effects are already shown in their reports. The application receives the stock updates, can calculate the difference ratio between the old and the new price, and sends an alert to the user.

Like everything in life, change is inevitable, and Stocks R Us decides to change its stock information source. Luckily, you abstracted the source with your StockTicker class so the StockTicker is the only class that needs to be changed.

After the source change, you start to receive complaints on crashes and other bugs such as missing alerts or unnecessary alerts. And so you start to investigate the problem and find it has something to do with concurrency.

2.1.1. Dealing with concurrency

It may not seem obvious, but the code hides a problem: concurrency. Nothing in the StockTicker interface promises anything about the thread in which the tick event will be raised, and nothing guarantees that a tick won’t be raised while another one is processed by your StockMonitor, as shown in figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2. Multiple threads executing the eventhandler code at the same time. Each box represents the execution time of a stock. While the first thread is running the code for MSFT, the second thread starts executing for the GOOG stock. Then the third thread starts for the same stock symbol as the first thread.

The StockMonitor class you wrote uses a dictionary to keep the information about the stocks, but the dictionary you’re using isn’t thread-safe.

Thread safety of a code portion means that the code works correctly when called from more than one thread, no matter the order in which those threads execute the code and without any need for synchronization of the calling code.

A class is called thread-safe if any one of its methods is thread-safe, even if different methods are called from different threads simultaneously. This usually means the inner data structures are protected from modifications at the same time.

The dictionary you’re using does support multiple readers at the same time, but if the dictionary is read while it’s being modified, an exception is thrown. This situation is illustrated in table 2.1. Thread1 (on the left) reaches the marked code, where it tries to get the StockInfo for a stock with the symbol symbol1. At the same time, Thread2 (on the right) reaches the line of code that adds a new StockInfo (with a symbol2 symbol) to the dictionary. Both the reading and the mutating of the dictionary is happening at the same time and leads to an exception.

Table 2.1. Reading and modifying the dictionary at the same time from two threads

|

Thread 2 |

|

|---|---|

:

:

var stockInfoExists =

_stockInfos.TryGetValue(symbol1,

out stockInfo);

if (stockInfoExists)

{

:

:

}

else

{

_stockInfos[symbol1] = new StockInfo(symbol1, price);

}

|

:

:

var stockInfoExists = _stockInfos.TryGetValue(symbol2,out stockInfo);

if (stockInfoExists)

{

:

:

}

else

{

_stockInfos[symbol2] = new

StockInfo(symbol2, price);

}

|

You can overcome this problem by using the .NET ConcurrentDictionary. This lock-free collection internally synchronizes the readers and writers so no exception will be thrown.

Unfortunately, ConcurrentDictionary isn’t enough, because the ticks aren’t synchronized by StockTicker. If you handle two (or more) ticks of the same stock at the same time, what’s the value of the PrevPrice property? There’s a nondeterministic answer to that question: the last one wins. But the last one isn’t necessarily the last tick that was raised, because the order in which the threads are running is determined by the OS and isn’t deterministic.[1] This makes your code unreliable, because the end user could be notified on an incorrect conclusion that your code makes. The OnStockTick event handler holds a critical section, and the way to protect it is by using a lock.

Deterministic means that no randomness is involved in the development of future states of the system.

Listing 2.8. Locked version of OnStockTick

Using locks is a perfect solution for many cases. But when you start to add locks in various places in an application, you can end up with a performance hit, because locks can increase execution time as well as the time that threads wait for the critical section to become available. The harder problem is that locks can cause your application to get into a deadlock, as shown in figure 2.3. Each thread is holding a resource that another thread needs, while at the same time they each are waiting for a resource that the other holds.

Figure 2.3. A deadlock: Thread 1 is holding the resource R1 and waiting for the resource R2 to be available. At the same time, Thread 2 is holding resource R2 and waiting for resource R1. Both threads will remain locked forever if no external intervention occurs.

Working with multithreaded applications is difficult, and no magic solution exists. The only reasonable thing to do is to make the code that will run multithreaded easier to understand, and make going into the trap of working with concurrent code more difficult.

Rx provides operators to run concurrent code, as you’ll see later in this chapter. For now, let’s step back, look at what you’ve created, and analyze it to see whether you can do better.

2.1.2. Retrospective on the solution and looking at the future

Thus far, our code gives a solution to the requirements Mr. Penny described at the beginning of the chapter. Functionally, the code does everything it needs to do. But what’s your feeling about it? Is it readable? Does it seem to be maintainable? Is it easy to extend? I’d like to point your attention to a few things.

Code scattering

Let’s start with the scattering of the code. It’s a well-known fact that scattered code makes a program harder to maintain, review, and test. In our example, the main logic of the program is in the OnStockTick event handler that’s “far” from the registration of the event:

It’s common to see classes that handle more than one event (or even many more), with each one in its own event handler, and you can start to lose sight of what’s related to what:

Many times developers choose to change the event-handler registration to a lambda expression such as

anObject.SomeEvent += (sender, eventArgs)=>{...};

Although you moved the event-handler logic to the registration, you added a bug to your resource cleaning. How do you unregister? The -= operator expects you to unregister the same delegate that you registered. A lambda expression can be unregistered only as follows:

eventHandler = (sender, eventArgs)=>{...};

anObject.SomeEvent += eventHandler;

:

anObject.SomeEvent -= eventHandler;

This looks unclean, so now you need to save the eventHandler as a member if you need to unregister from it, which leads me to the next point.

Resource handling

The unregistration from the event and the rest of the resources cleanup that you added to support your code (such as the dictionary) took place in the Dispose method. This is a well-used pattern, but more frequently than not, developers forget to free the resources that their code uses. Even though C# and .NET as a whole are managed and use garbage collection, many times you’ll still need to properly free resources to avoid memory leaks and other types of bugs. Events are often left registered, which is one of the main causes of memory leaks. The reason (at least for some) is that the way we unregister doesn’t feel natural for many developers, and deciding the correct place and time to unregister isn’t always straightforward—especially because many developers prefer to use the lambda style of registering events, as I stated previously. Beside the event itself, you added code and state management (such as our dictionary) to support your logic. Many more types of applications handle the same scenarios, such as filtering, grouping, buffering, and, of course, the cleaning of what they bring. This brings us to the next point.

Repeatability and composability

To me, our logic also feels repeatable. I swear I wrote this code (or similar code) in a past application, saving a previous state by a key and updating it each time an update comes in, and I bet you feel the same. Moreover, I also feel that this code isn’t composable, and the more conditions you have, the more inner if statements you’ll see and the less readable your code will be. It’s common to see this kind of code in an application, and with its arrowhead-like structure, it’s becoming harder to understand and follow what it does:

if (some condition) { if (another condition) { if (another inner condition) { //some code } } } else { if (one more condition) { //some code } else { //some code } }

Composition is the ability to compose a complex structure from simpler constructs.

This definition is similar to that in mathematics, where you can compose a complex expression from a set of other functions: f(x) = x2 + sin(x)

Composition also allows us to use a function as the argument of another function:

g(x) = x + 1

f(g(x)) = (x + 1)2 + sin(x + 1)

In computer science, we use composition to express complex code with simpler functions. This allows us to make higher abstractions and concentrate on the purpose of the code and less on the details, making it easier to grasp.

If you were given new requirements to your code, such as calculating the change ratio by looking at more than two consecutive events, your code would have to change dramatically. The change would be even more dramatic if the new requirement was time based, such as looking at the change ratio in a time interval.

Synchronization

Synchronization is another thing that developers tend to forget, resulting in the same problems that we had: unreliable code due to improperly calculated values, and crashes that might occur when working with non-thread-safe classes. Synchronization is all about making sure that if multiple threads reach the same code at the same time (virtually, not necessarily in parallel, because a context switch might be involved), then only one thread will get access. Locks are one way to implement synchronization, but other ways exist and do require knowledge and care.

It’s easy to write code that isn’t thread-safe, but it’s even easier to write code with locks that lead to deadlocks or starvation. The main issue with those types of bugs is that they’re hard to find. Your code could run for ages (literally), until you run into a crash or other error.

With so many points from such a small program, it’s no wonder people say that programming is hard. It’s time to see the greatness of Rx and how it makes the issues we’ve discussed easier to overcome. Let’s see the Rx way and start adding Rx to your application.

2.2. Creating your first Rx application

In this section, the Rx example uses the same StockTicker that you saw in the previous section, but this time you won’t work with the traditional standard .NET event. Instead you’ll use IObservable<T>, which you’ll create, and then write your event-processing flow around it. You’ll go slowly and add layer after layer to the solution until you have a fully running application that’s easier to read and extend.

Every journey starts with the first step. You’ll begin this journey by creating a new project (a console application will do) and adding the Rx libraries.

2.2.1. Selecting Rx packages

The first step in working with Reactive Extensions is adding the library to your project. No matter whether you write a Windows Presentation Foundation (WPF) application, ASP.NET website, Windows Communication Foundation (WCF) service, or a simple console application, Rx can be used inside your code to benefit you. But you do need to select the correct libraries to reference from your project.

The Rx library is deployed as a set of a portable class libraries (PCLs)[2] and platform-specific providers that you install depending on your project platform. This is shown in figure 2.4.

The Portable Class Library project enables you to build assemblies that work on more than one .NET Framework platform. For details, see http://mng.bz/upA5.

Figure 2.4. Rx assemblies are a set of portable class libraries (middle and bottom) and platform-specific libraries (top left). The PlatformServices assembly holds the platform enlightments that are the glue between the two.

To add the necessary references to your project, you need to select the appropriate packages from NuGet, a .NET package manager from which you can easily search and install packages (which usually contain libraries). Table 2.2 describes the Rx packages you can choose from at the time of this writing and figure 2.5 shows the NuGet package manager.

Figure 2.5. Reactive Extensions NuGet packages. Many packages add things on top of Rx to identify the Rx.NET-specific libraries. Look for a package ID with the prefix System.Reactive and make sure the publisher is Microsoft.

Note

Rx 3.0, published in June 2016, added Rx support to the .NET Core and Universal Windows Platform (UWP). Rx.NET also joined the .NET Foundation (www.dotnetfoundation.org/projects). To conform with the naming convention used by .NET Core, the Rx packages were renamed to match their library names, and the previous Rx packages are now hidden in the NuGet gallery.

Table 2.2. Rx packages

|

Package name |

Description |

|---|---|

| System.Reactive.Interfaces (Rx-Interfaces prior to Rx 3.0) | Installs the System.Reactive.Interfaces assembly that holds only interfaces that other Rx packages depend on. |

| System.Reactive.Core (Rx-Core prior to Rx 3.0) | Installs the System.Reactive.Core assembly that includes portable implementations of schedulers, disposables, and others. |

| System.Reactive.Linq (Rx-Linq prior to Rx 3.0) | Installs the System.Reactive.Linq assembly. This is where the query operators are implemented. |

| System.Reactive.PlatformServices (Rx-PlatformServices prior to Rx 3.0) | Installs the System.Reactive.PlatformServices assembly. This is the glue between the portable and nonportable Rx packages. |

| System.Reactive (Rx-Main prior to Rx 3.0) | This is the main package of Rx and what you’ll install in most cases. It includes System.Reactive.Interfaces, System.Reactive.Core, System.Reactive.Linq, and System.Reactive.PlatformServices (the specific enlightenments provider that will be used depends on the project platform). |

| System.Reactive.Providers (Rx-Providers prior to Rx 3.0) | Installs System.Reactive.Providers together with the System.Reactive.Core package. This package adds the IQbservable LINQ API operators that allow creating the expression tree on the event tree so that the query provider can translate to a target query language. This is the Rx IQueryable counterpart. |

| System.Reactive.Windows.Threading (Rx-Xaml prior to Rx 3.0) | Installs the System.Reactive.Windows.Threading assembly together with the System.Reactive.Core package. Use this package when you need to add UI synchronization classes for any platform that supports the XAML dispatcher (WPF, Silverlight, Windows Phone, and Windows Store apps). |

| System.Reactive.Runtime.Remoting (Rx-Remoting prior to Rx 3.0) | Installs System.Reactive.Runtime.Remoting together with the System.Reactive.Core package. Use this package to add extensions to .NET Remoting and expose it as an observable sequence. |

| System.Reactive.Windows.Forms / System.Reactive.WindowsRuntime (Rx-WPF/Rx-Silverlight/Rx-WindowsStore/Rx-WinForms prior to Rx 3.0) | Subset of packages that’s specific to the platform. Add UI synchronization classes and Rx utilities for the platform types (such as IAsyncAction and IAsyncOperationWithProgress in WinRT). |

| Microsoft.Reactive.Testing (Rx-Testing prior to Rx 3.0) | The Rx testing library that enables writing reactive unit tests. Appendix C includes explanations and examples of reactive unit tests. |

| System.Reactive.Observable.Aliases (Rx-Aliases prior to Rx 3.0) | Provides aliases for some of the query operators such as Map, FlatMap, and Filter. |

Most of the time, you’ll add the System.Reactive package to your project because it contains the types that are most used. When you’re writing to a specific platform or technology, you’ll add the complementary package.[3]

Although the examples in the book are in C#, you can use Rx with other .NET languages. Also, if you’re using F#, look at http://fsprojects.github.io/FSharp.Control.Reactive, which provides F# wrappers for Rx.

2.2.2. Installing from NuGet

After you decide which package you need, you can install it from the Package Manager dialog box or the Package Manager console. To use the Package Manager console, choose Tools > NuGet Package Manager > Package Manager Console. In the console, select the destination project from the Default Project drop-down list, shown in figure 2.6.

Figure 2.6. Installing the Rx libraries through the Package Manager console. Make sure you select the correct project for installation from the Default Project drop-down list. You can also define the project by typing -ProjectName [project name].

In the console, write the installation command of the package you need:

Install-Package [Package Name]

Another option for installing the packages is through the Package Manager dialog box, shown in figure 2.7. This UI enables you to search for packages and see their information in a more user-friendly way. Right-click your project and choose Manage NuGet Packages. Type in the package name, select the package you want to install from the drop-down list, and then click Install.

Figure 2.7. NuGet Package Manager from VS 2015. Search for the package you want by typing its name

After the NuGet package is installed, you can write the Rx version of Stock-Monitor. You can find the entire code at the book’s source code in the GitHub repository: http://mng.bz/18Pr.

Microsoft recently announced that the format I describe here is deprecated (but will be supported in the transition time). Microsoft recommends using the normal csproj file with the new MSBuild additions (PackageReference for example). To use .NET Core, you first need to install the latest version from www.microsoft.com/net/core. Then, create a new project in your favorite tool, such as Visual Studio 2015 or Visual Studio Code (https://code.visualstudio.com/docs/runtimes/dotnet).

Add a reference to the System.Reactive NuGet package by updating the dependencies section inside the project.json file, as shown here:

{

"version": "1.0.0-*",

"buildOptions": {

"debugType": "portable",

"emitEntryPoint": true

},

"dependencies": { "System.Reactive": "3.0.0" },

"frameworks": {

"netcoreapp1.0": {

"dependencies": {

"Microsoft.NETCore.App": {

"type": "platform",

"version": "1.0.0"

},

},

"imports": "dnxcore50"

}

}

}

Finally, run the dotnet restore command at the command prompt. You now have a configured Rx project.

2.3. Writing the event-processing flow

After you install the Rx package that adds the needed references to the Rx libraries, you can start building your application around it. To start creating the event-processing flow, you need the source of the events. In Rx, the source of events (the publisher, if you prefer) is the object that implements the IObservable<T> interface.

To recap, the IObservable<T> interface defines the single method Subscribe that allows observers to subscribe to notifications. Observers implement the IObserver interface that defines the methods that will be called by the observable when there are notifications.

Rx provides all kinds of tools to convert various types of sources to IObservable<T>, and the most fundamental tool that’s included is the one that converts a standard .NET event into an observable.

In our example of creating an application that provides notifications of drastic stock changes, you’ll continue to work with the StockTick event. You’ll see how to make it into an observable that you can use to do magic.

2.3.1. Subscribing to the event

StockTicker exposes the event StockTick that’s raised each time an update occurs on a stock. But to work with Rx, you need to convert this event into an observable. Luckily, Rx provides the FromEventPattern method that enables you to do just that:

The FromEventPattern method has a couple of overloads. The one you’re using here takes two generic parameters and two method parameters. Figure 2.8 shows the method signature explanation.

Figure 2.8. FromEventPattern method signature

The addHandler and removeHandler parameters register and unregister the Rx handler to the event; the Rx handler will be called by the event and then will call the OnNext method of the observers.

Unwrapping the EventArgs

The ticks variable now holds an observable of type IObservable<EventPattern <StockTick>>. Each time the event is raised, the Rx handler is called and wraps the event-args and the event source into an object of EventPattern type that will be delivered to the observers through the OnNext method. Because you care only for the StockTick (the EventArgs in the EventPattern type) of each notification, you can add the Select operator that will transform the notification and unwrap the EventArgs so that only the StockTick will be pushed down the stream:

2.3.2. Grouping stocks by symbol

Now that you have an observable that carries the ticks (updates on the stocks), you can start writing your query around it. The first thing to do is to group the ticks by their symbols so you can handle each group (stock) separately. With Rx, this is an easy task, as shown in figure 2.9.

Figure 2.9. A simple grouping of the stock ticks by the quote symbol

This expression creates an observable that provides the groups. Each group represents a company and is an observable that will push only the ticks of that group. Each tick from the ticks source observable is routed to the correct observable group by its symbol. This is shown in figure 2.10.

Figure 2.10. The ticks observable is grouped into two company groups, each one for a different symbol. As the notifications are pushed on the ticks observable, they’re routed to their group observable. If it’s the first time the symbol appears, a new observable is created for the group.

This grouping is written with a query expression. Query expressions are written in a declarative query syntax but are a sugar syntax that the compiler turns into a real chain of method calls. This is the same expression written in a method syntax:

ticks.GroupBy(tick => tick.QuoteSymbol);

2.3.3. Finding the difference between ticks

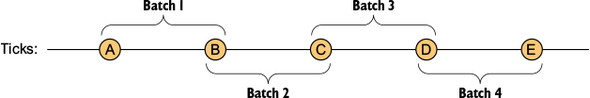

The next step on your way to finding any drastic changes is to compare two consecutive ticks to see whether the difference between them is higher than a particular ratio. For this, you need a way to batch the ticks inside a group so you can get two ticks together. The batching should be done in such a way that two consecutive batches will include a shared tick; the last tick in a batch will be the first one in the next batch. Figure 2.11 shows an example of this batching.

Figure 2.11. Ticks are batched together. Each batch has two items; two consecutive batches have a shared item.

To create batches on an observable sequence, you use the Buffer operator. Buffer gets as parameters the number of items you want in a batch—two, in this case—and the number of items to skip before opening a new batch. You need to skip one item before opening a new batch, thus making one item shared between two batches. You need to apply the Buffer method to each group by writing the following:

company.Buffer(2, 1)

The Buffer method outputs an array that holds the two consecutive ticks, as shown in figure 2.12. This enables you to calculate the difference between the two ticks to see whether it’s in the allowed threshold.

Figure 2.12. After applying the Buffer(...) method on each group, you a get new type of notification that holds an array of the two consecutive ticks.

By using the Let keyword, Rx allows you to keep the calculation in a variable that will be carried on the observable:

from tick in ticks group tick by tick.QuoteSymbol into company from tickPair in company.Buffer(2, 1) let changeRatio = Math.Abs((tickPair[1].Price - tickPair[0].Price) / tickPair[0].Price)

This code fragment includes all your steps until now. Applying the buffering on the company observable creates a new observable that pushes the buffers of two ticks. You observe its notifications by using the from ... in ... statement. Each notification is represented by the tickPair variable.

You then introduce the changeRatio variable that holds the ratio of change between the two ticks; this variable will be carried on the observable to the rest of your query, as shown in figure 2.13.

Figure 2.13. From each pair of consecutive ticks per company group, you calculate the ratio of difference.

Now that you know the change ratio, all that’s left is filtering out all the notifications that aren’t interesting (not a drastic change) and keeping only those that are above your wanted ratio by applying the Where(...) operator:

The drasticChanges variable is an observable that pushes notifications only for ticks that represent a change in a stock price that’s higher than maxChangeRatio. In figure 2.14, the maximum change ratio is 10%.

Figure 2.14. After filtering the notifications with the Where operator, you find that only one notification is a drastic change.

To consume the drastic change notifications, you need to subscribe to the drasticChange observable. Then you can notify the user by printing it to the screen.

2.3.4. Cleaning resources

If the user doesn’t want to receive any more notifications about drastic changes, you need to dispose of the subscription to the drasticChanges observable. When you subscribed to the observable, the subscription was returned to you, and you stored it in the _subscription class member.

As before, the StockMonitor Dispose method (which is provided because you implemented the IDisposable interface) makes a perfect fit. The only thing you need to do in your Dispose method is to call to Dispose method of the subscription object:

public void Dispose() { _subscription.Dispose(); }

Notice that you don’t need to write anything about delegates involved in the processing of your query, and you don’t need to clean up any data structures related to the storage of the previous ticks data. All of those are kept in the Rx internal operators implementation, and when you dispose of the subscription, a chain of disposals happen, causing all the internal data structures to be disposed of as well.

2.3.5. Dealing with concurrency

In the traditional events version, you needed to add code to handle the critical section in your application. This critical section enabled two threads to reach the event handler simultaneously and read and modify your collection of past ticks at the same time, leading to an exception and miscalculation of the change ratio. You added a lock to synchronize the access to the critical section, which is one way to provide synchronization between threads.

With Rx, adding synchronization to the execution flow is much more declarative. Add the Synchronize operator to where you want to start synchronizing, and Rx will take care of the rest. In this case, you can add synchronization from the beginning, so you add the Synchronize operator when creating the observable itself:

It doesn’t get any simpler than that, but as before, you need to remember that every time you add synchronization of any kind, you risk adding a probable deadlock. Rx doesn’t fix that, so developer caution is still needed. Rx only gives you tools to make the introduction of synchronization easier and more visible. When things are easy, explicit, and readable, chances increase that you’ll make it right, but making sure you do it correctly is still your job as a developer.

2.3.6. Wrapping up

Listing 2.9 shows the entire code of the Rx version. The main difference from the traditional events example is that the code tells the story about what you’re trying to achieve rather than how you’re trying to achieve it. This is the declarative programming model that Rx is based on.

Listing 2.9. Locked version of OnStockTick

It’s now a good time to compare the Rx and events versions.

Keeping the code close

In the Rx example, all the code that relates to the logic of finding the drastic changes is close together, in the same place—from the event conversion to the observable to the subscription that displays the notifications onscreen. It’s all sitting in the same method, which makes navigating around the solution easier. This is a small example, and even though all the code sits together, it doesn’t create a huge method. In contrast, the traditional events version scattered the code and its data structures in the class.

Providing better and less resource handling

The Rx version is almost free of any resource handling, and those resources that you do want to free were freed explicitly by calling Dispose. You’re unaware of the real resources that the Rx pipeline creates because they were well encapsulated in the operators’ implementation. The fewer resources you need to manage, the better your code will be in managing resources. This is the opposite of the traditional events version, in which you needed to add every resource that was involved and had to manage its lifetime, making the code error prone.

Using composable operators

One of the hardest computer science problems is naming things—methods, classes, and so on. But when you give a good name to something, it makes the process of using it later easy and fluid. This is exactly what you get with the Rx operators. The Rx operators are a recurring named code pattern that reduces the repeatability in your code that otherwise you’d have to write by yourself—meaning now you can write less code and reuse existing code. With each step of building your query on the observable, you added a new operator on the previously built expression; this is composability at its best. Composability makes it easy to extend the query in the future and make adjustments while you’re building it. This is contrary to the traditional events version, in which no clear separation exists between the code fragments that handled each step when building the whole process to find the drastic change.

Performing synchronization

Rx has a few operators dedicated specifically to concurrency management. In this example, you used only the Synchronize operator that, as generally stated before about Rx operators, saved you from making the incorrect use of a lock by yourself. By default, Rx doesn’t perform any synchronization between threads—the same as regular events. But when the time calls for action, Rx makes it simple for the developer to add the synchronization and spares the use of the low-level synchronization primitives, which makes the code more attractive.

2.4. Summary

This chapter presented a simple yet powerful example of something you’ve probably done in the past (or might find yourself doing in the future) and solved it in two ways: the traditional events style and the Rx style of event-processing flow.

- Writing an event-driven application in .NET is very intuitive but holds caveats regarding resource cleanup and code readability.

- To use the Rx library, you need to install the Rx packages. Most often you’ll install the System.Reactive package.

- You can use Rx in any type of application WPF desktop client, an ASP.NET website, or a simple console application and others.

- Traditional .NET events can be converted into observables.

- Rx allows you to write query expression on top of the observable.

- Rx provides many query operators such as filtering with the Where operator, transformation with Select operator, and others.

This doesn’t end here, of course. This is only the beginning of your journey. To use Rx correctly in your application and to use all the rich operators, you need to learn about them and techniques for putting them together, which is what this book is all about. In the next chapter, you’ll learn about the functional way of thinking that, together with the core concepts inside .NET, allowed Rx to evolve.