Chapter 11. Error handling and recovery

- Reacting to errors

- Properly freeing resources

- Dealing with backpressure

Errors happen; that’s a fact of programming life. To provide high-quality service to the users of your applications, you must make sure your code handles errors and gracefully recovers when they happen. Otherwise, users experience application crashes or incorrect behavior (such as wrong computations or unexpected alerts) that can eventually turn them away from your product. In the case of an error, you might want to swallow it and continue, or add specific handling for a specific error. If an observable periodically emits updates from a central server, and one of the updates causes an unexpected error (for example, a network disconnection), handling the error by resubscribing observers to get the next set of updates might be the best solution. This chapter teaches you about the kinds of error-handling operators you can use to ensure that your observable pipeline is protected.

In addition to handling errors, you can prevent certain errors in advance, such as improper resource handling that can cause memory leaks, and unclosed server connections. An observable emitting at a rate faster than the rate the observer can consume is known as backpressure, which can result in errors and a high consumption of resources. This chapter shows you how to control the lifetime of your resources properly, even in the case of unexpected errors, and gives you solutions to backpressure.

11.1. Reacting to errors

In the .NET world, error means an exception, and an exception can be thrown for many reasons. Some (OutOfMemoryException, for example) aren’t even under your control. It’s important to differentiate the various places (or phases) an exception can be thrown from inside the observable pipeline because for different places you’ll need different types of handling.

In the reactive pipeline, errors can happen in these four places:

- In the observable Subscribe method call during subscription

- In the observable code as it prepares the values to emit after subscription (for example, the observable tries to pull data from an external source that’s disconnected)

- In operator code (for example, the selector function you provided for the Select operator throws an exception)

- In the observer’s OnNext, OnCompleted, and OnError functions

For the first three cases, the Rx guidelines state that the observer should be notified of the error via its OnError function and the observer subscription will terminate, meaning no more notifications from the observable will be observed by the observer.

In the last case, where the observer is the one responsible for the error, it’s the responsibility of the observer (and the developer) to handle the error. Rx provides no guarantee of what will happen in this case.

Note

I’d like to stress the last point again. If the code inside the observer function throws an exception, there’s nothing in the Rx package to save you. So if you didn’t provide an error-handling routine using a try-catch block around the “risky” code, the caller thread will have an unhandled exception. This will cause your process to terminate. This isn’t different from any other code in your application that throws an exception that nobody handled. Your only option here is to make sure your code doesn’t throw unwanted exceptions.

11.1.1. Errors from the observable side

Now that you understand that you must take care of exceptions that happen in the observer code explicitly, let’s talk about the other three cases in the preceding list, where the exception is thrown by the observable or one of the operators in the pipeline.

The Rx Design Guidelines guarantee that errors from those places are propagated to the observer’s OnError function. This makes error handling easy for you, because you now have a single place where you can react to them—the OnError function, depicted in figure 11.1. The OnError function receives a single argument (the Exception that was thrown) so your code can investigate what exactly that exception is and react to it.

Figure 11.1. When an exception is thrown in the pipeline by the observable or one of the operators, it’s propagated to the OnError function of the observer.

Listing 11.1 creates an observable that produces an error of type OutOfMemory-Exception. The weather simulation application implements a weather prediction observable that runs a data-intensive computation and then emits its results. Because the computation also creates a lot of data stored in memory, there’s a risk of running out of memory. If this exception occurs, as a last resort the observer can run garbage collection (GC) together with Large Object Heap (LOH) compaction[1] to try to free memory.

This is available for .NET version 4.5.1 and up, http://mng.bz/NVW5.

Listing 11.1. Typical implementation of the observer’s OnError function

One thing that you might think when looking at this example from the developer’s standpoint is that reacting to errors isn’t code friendly. You’re absolutely right. You have to do type checking to see what the exception type is and, for each type of exception, the error handling requires your manual intervention, even if all you want to do is to dismiss it.

The Rx team realizes that developers tend to have common responses to errors happening in the observable pipeline. Those responses include catching a specific exception type and doing something accordingly, or dismissing the error and resuming the execution with the original observable or another observable.

The Rx team, making sure the observable pipeline code will continue to be declarative and concise, created specific operators to make the developer’s life easier.

11.1.2. Catching errors

In the traditional imperative programming model, you use a try-catch block around the potentially erroneous code and, in each catch block, specify the type of the exception you want to handle or leave it empty to say it should handle all exception types. After the catch code finishes, the application continues its work.

Semantically, the Rx Catch operator does the same thing, handling a specific exception type, but the way to specify the continuation of execution is by stipulating a fallback observable. In the case of an error, the observer is subscribed to the fallback observable (figure 11.2).

Figure 11.2. The Catch operator lets you handle a specific exception type and set a fallback observable in case an exception is thrown.

In the next example, you improve the error handling for the weather simulation observable shown in listing 11.1. Now, you add the Catch operator to handle the OutOfMemoryException and gracefully close the observable pipeline:

The output is as follows:

handling OOM exception Catch (source throws) - OnCompleted()

Catch receives a function that handles a specific exception type; the function returns the observable that will be used for continuing execution of the observable pipeline. In this example, you return an empty observable so that the observable pipeline will complete, but in your code, this can be a fallback observable that will emit values instead of the original observable.

IObservable<TSource> Catch<TSource, TException>( IObservable<TSource> source, Func<TException, IObservable<TSource>> handler) where TException : Exception

If you want to return the same observable for any type of exception that might be thrown in the observable pipeline, you can use the Catch overload that receives only the observable that will be used in case of an error.

The next error gracefully finishes, in case the weather simulation observable signals an error:

weatherSimulationResults

.Catch(Observable.Empty<WeatherSimulation>())

.SubscribeConsole("Catch (handling all exception types)");

OnErrorResumeNext—a variant of Catch

The Catch operator concatenates observables if an error occurs. In chapter 10, you learned about the Concat operator. It also concatenates an observable, so when the first observable successfully completes, the second observable is being subscribed to and the observer receives its notifications. It makes sense to extend the Concat operator so concatenation happens not only when the observable completes, but also when it fails. This is the responsibility of the OnErrorResumeNext operator, illustrated in figure 11.3.

Figure 11.3. The OnErrorResumeNext operator is a hybrid of the Catch operator and the Concat operator.

The next example shows how to concatenate weather reports coming from two weather stations. The example shows that even if the first weather station observable (Station A) is terminated with an error, the second observable (Station B) is concatenated:

IObservable<WeatherReport> weatherStationA = Observable.Throw<WeatherReport>(new OutOfMemoryException()); IObservable<WeatherReport> weatherStationB = Observable.Return<WeatherReport>(new WeatherReport() { Station = "B", Temperature = 20.0 }); weatherStationA .OnErrorResumeNext(weatherStationB) .SubscribeConsole("OnErrorResumeNext(source throws)"); weatherStationB .OnErrorResumeNext(weatherStationB) .SubscribeConsole("OnErrorResumeNext(source completed)");

Running the example shows this output, where only Station B reports are received:

OnErrorResumeNext(source throws) - OnNext(Station: B, Temperature: 20) OnErrorResumeNext(source throws) - OnCompleted() OnErrorResumeNext(source completed) - OnNext(Station: B, Temperature: 20) OnErrorResumeNext(source completed) - OnNext(Station: B, Temperature: 20) OnErrorResumeNext(source completed) - OnCompleted()

With both Catch and OnErrorResumeNext operators, it’s possible the concatenated observable is the original observable that throws the exception. In the case of an error, this resubscribes the observer to the observable. Conceptually, this means you want to retry the operation; however, you may want to limit the number of retries or explicitly set the number of retries to infinity. To make it easier for you to set the number of retries, use the Retry operator.

11.1.3. Retrying to subscribe in case of an error

The Retry operator, illustrated in figure 11.4, resubscribes an observer to the observable if an error occurs. Remember, the Rx guidelines state that if an error occurs, the subscription between the observer and observable is disconnected. If the observable is cold (which means the set of notifications isn’t shared between the observers, such as an observable that reads lines from a file), the Retry operator will cause the observer to resubscribe, and the observable sequence will regenerate and possibly fail again. If the observable is hot, the new subscription will allow the observer to receive the ensuing emitted notifications.

Figure 11.4. The Retry operator resubscribes the observer to the observable when an error is emitted. In the case of a hot observable, as shown in the figure, the observer receives the rest of the emitted notifications.

Note

Observable temperature is explained in chapter 7.

In the next example, the observable simulates weather reports received from a weather station. It’s possible that the connection to the station fails due to a transient[2] error (such as a low network reception) and retrying is the best possible option. Of course, it’s possible that the error isn’t transient, so you’ll want to limit the number of retries (in this case to three attempts), as shown in figure 11.5.

A transient is a property of any element in the system that is temporary. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transient_(computer_programming).

Figure 11.5. The Retry operator automatically resubscribes to the weather station observable in the case of an error.

Running the example shows this output (I removed some of the output for readability):

- OnError:

System.OutOfMemoryException: Insufficient memory to continue ...

- OnError:

System.OutOfMemoryException: Insufficient memory to continue ...

- OnError:

System.OutOfMemoryException: Insufficient memory to continue ...

Retry - OnError:

System.OutOfMemoryException: Insufficient memory to continue ...

You can see that the error is thrown four times. The first three messages are printed because of the original error and the first two retries, and the last message is from the last attempt to retry, which in this case causes the error again, and is received by the observer OnNext function.

Note

If you leave the Retry operator empty (without passing a number), the retries occur infinite times.

Next, I’ll show you how to control the lifetime of the resources you use as part of your observable pipeline so that you can properly discard them.

11.2. Controlling the lifetime of resources

As part of the observable pipeline construction, different resources are allocated and used. This includes primitives and simple objects that occupy memory and resources that aren’t managed (such as handles to files or connections to external services). When the observable pipeline completes, either because the observable finishes its emissions or because the subscription is disposed of, it’s important to free the resources that were allocated. It’s twice as important to handle the deallocation of those resources when an error occurs; otherwise, your attempts to recover from the error might be doomed in advance (for example, a file might be locked because its handle wasn’t freed).

The good news is that Rx operators take care of themselves and clean whatever they use. So you need to take care of only the things that you create and work with in the observable pipeline.

11.2.1. Disposing in a deterministic way

In .NET, the GC deallocates managed objects in a nondeterministic way. Even if an object is no longer in use (there are no root references to it), the object can stay in memory for a long time until the GC runs. Some managed objects might use unmanaged resources, such as connections or file handles and, in this case, it’s important to dispose of them as soon as possible when they’re no longer needed. This makes the disposal deterministic.

In .NET, you can achieve a deterministic disposal of resources by implementing the IDisposable interface on the class that holds the resource and by implementing the Dispose method with the code that frees the resource. During runtime, when you’re finished using the resource (and the object that wraps it), you can invoke the Dispose method to free the resource. Of course, the managed memory of the wrapping object or any other objects used by the resource is reclaimed by the GC (garbage collection is nondeterministic in nature).

In C#, the easiest and safest way of working with an object of a type that implements the IDisposable interface is with the using statement:

class DisposableType : IDisposable { public void Dispose() { /*Freeing the resource*/ } } private static void TraditionalUsingStatement() { using (var disposable = new DisposableType()) { //Rest of code } }

When the execution reaches the end of the block, the Dispose method is automatically called, even if it’s due to an exception thrown inside the block.

Alternatively, you can call the Dispose method and not use the using statement. This is usually done when the location of the creation of the disposable object is different from the location of where you need to dispose of it.

Because you’d like to use the same semantics of deterministic disposal inside your observable pipeline, Rx provides the Using operator, which works similarly to the using statement.

In our sample application, suppose you need to work with an observable that emits notifications coming from a heat sensor, and you’re trying to trace a problem that’s happening in your code. You want to write the notifications to a log file so you can analyze it later. When working with files, it’s important to close the file when you’re finished; otherwise, no one else can work with it, and the data that wasn’t flushed to it disappears. Here’s how to make sure the file handle will be disposed of:

The use of the Using operator looks similar to the using statement in that you create the resource and then use the created resource inside the block. The main difference is that the inner block (the second parameter) needs to return the observable that uses the resource, as shown in figure 11.6.

Figure 11.6. The Using operator creates a disposable resource that has the same lifespan as the observable.

The Using operator receives two parameters: the first is the resource factory (a function that creates the disposable object), and the second is the observable factory (a function that receives the disposable object and returns an observable that uses it).

The Using operator returns an observable that wraps the process of invoking the resource factory and then the observable factory every time an observer subscribes. The Using operator disposes of the resource when the observable terminates, no matter for what reason.

Here’s an example that proves it:

In the resource factory, you create a disposable object that prints a message when it’s disposed of. You use a Subject as the observable that you return from the observable factory. You then test what happens when the subject emits the notifications of OnCompleted and OnError, and also what happens when the subscription object itself is disposed of.

In all of these tests, the resource is disposed of. Note that between each test case, you create a new Subject because a completed Subject is no longer usable and will automatically notify its completeness to any a new observer that subscribes to it.

If you run this program, this is the output you’ll see:

Disposed when completed

- OnCompleted()

DISPOSED

Disposed when error occurs

- OnError:

System.Exception: error

DISPOSED

Disposed when subscription disposed

DISPOSED

This proves that for any termination of the observable, or the subscription, the resource will be gracefully disposed of.

The Using operator also includes an asynchronous version, in which the resource factory and the observable factory return Tasks:

IObservable<TResult> Using<TResult, TResource>( Func<CancellationToken, Task<TResource>> resourceFactoryAsync, Func<TResource, CancellationToken, Task<IObservable<TResult>>> observableFactoryAsync)

Because the factories are asynchronous, they both receive a cancellation token that will report cancellation in case the subscription was disposed of while the factories are still running. Other than that, the asynchronous version works the same as what you saw in the preceding synchronous version.

The Using operator works amazingly well when you need to dispose of resources. Nonetheless, in some cases cleanup operations aren’t exposed through a disposable object. In C#, when you have a piece of code that needs to run at the end of an operation, no matter whether the operation succeeded or failed, you use the try-finally statement. Rx provides similar semantics.

11.2.2. Deterministic finalization

The Finally operator, illustrated in figure 11.7, works similarly to the finally block in C#. At the end of an operation, no matter whether it succeeded or failed, a piece of code is executed.

Figure 11.7. The Finally operator registers an action to take on the observable or subscription termination.

The code in the finally block usually handles cleanup of things that aren’t necessarily disposable, and it runs the code related to the closure of a logical transaction. The Finally operator does the same thing for the observable: it runs the code you need to execute when the observable terminates—successfully or with an error.

Suppose you have a window that shows the progress of an operation (for example, loading a file or running a lengthy or complicated computation), and you want to close the window programmatically, no matter whether the operation succeeds or fails. This is how you can write code for that:

IObservable<int> progress =... progress .Finally(() =>{/*close the window*/}) .Subscribe(x =>{/*Update the UI /});

The piece of code that closes the window is called for in any case in which the observable terminates.

The next code example demonstrates the different cases when the action in the Finally clause is executed:

Running this example produces the following output:

Successful complete

- OnCompleted()

Finally Code

Error termination

- OnError:

System.Exception: error

Finally Code

Unsubscribing

Finally Code

The Finally operator can be helpful when you want to do the last step in the ongoing work of the observable and can’t express it with a disposable object (for example, closing a connection or sending a message to an external service).

Next, I’ll show you how to reduce the risk of having observers that are no longer necessary, yet never removed from memory—a situation called dangling observers.

11.2.3. Dangling observers

A dangling observer is the result of an observer being held (referenced) by nothing else but an observable, even though the logical lifetime of the observer has already finished. If the observer is the window that shows chat messages coming from the chat observable, it’s possible that the window object will still be referenced by the observable, even though the user has closed the window.

Dangling observers appear when an observer subscribes to an observable but never unsubscribes from it by disposing of the subscription object. I define the object that subscribes the observer and that’s in charge for its lifetime as the observer’s owner.

Dangling observers result in memory leaks because observers are objects that occupy memory. Dangling observers also result in unwanted (and unexpected) behavior because the observer still reacts to notifications although it shouldn’t. For example, the chat window mentioned previously still reacts to the chat messages and adds them to its inner collections even though it’s closed. Figure 11.8 depicts a dangling observer.

Figure 11.8. When an observer is subscribed to an observable, it remains alive, regardless of its creator.

As a reminder, when an observer is subscribed to an observable, you get in return a disposable object that holds the subscription. For example:

IObservable<int> observable = ... IDisposable subscription = observable.Subscribe(x =>{/*the observer code*/});

Unfortunately, many developers throw away the subscription object and don’t maintain it. Developers also forget to dispose of the subscription properly even if they do save it, which also results in a dangling observer.

If the observer holds references to other objects, this creates a chain of objects that aren’t collected. A special case of such a reference occurs when you implicitly create an observer via the Subscribe operator to which you send the OnNext, OnError, and OnCompleted functions. This implicitly creates a reference from the observer to the object that created the subscription if the functions use the object’s properties or methods.

Just to make it clear, if your application does need the observer to be kept alive for the lifetime of the observable it’s subscribed to, then leaving the observer dangled is the expected behavior. But, in many cases, the observer should be kept alive for the duration of its owner (or creator) and, in those cases, it’s crucial that you save the subscription and dispose of it when needed.

Note

One of the misunderstandings about the subscription object is the false assumption that when the GC collects the subscription, its Dispose method is called. Rx disposables don’t implement a finalizer and, if the GC collects it, the memory is reclaimed but the subscription isn’t. You can’t rely on the GC to unsubscribe observers for you.

In some cases, you can’t determine when the life of the subscription should end and you’d like to keep it dynamic so that when there are no more references to the observer (except from the observable), it should be disposed of. An example of such a case is when working with platforms such as Windows Phone, where the application pages are kept inside a backstack. (The backstack is what allows the user to press the Back key on the machine and navigate to the previous page.) The Windows Phone application can also clear the backstack when it wants to prevent user navigation (for example, when the user logs out and returns to the login page, all the previous pages visited are no longer relevant).

Suppose a page (or its ViewModel) subscribes to an observable. Because of the nondeterministic nature of the page’s lifetime, the page doesn’t know whether it’s still in the backstack. You have no way of knowing exactly when to dispose of the subscription. For those cases, you need a weak observer.

Creating a weak observer

The problem of dangling observers is similar to the problem of dangling event handlers. In traditional .NET events, the registration of the event handler to the event creates a reference from the event source to the object that contains the event handler (unless the event handler is static). So unless you unregister from the event with the -= operator, the object that contains the event handler will be kept alive as long as the event source is alive.

To remove this risk, a common pattern is to change the references held by the event to weak references.[3] The WeakReference class represents a reference that still allows the referenced object to be reclaimed by the GC. The code that uses the WeakReference object can query it to check whether the object is still alive.

A weak reference is a reference that doesn’t prevent the GC from collecting the object, http://mng.bz/73ux.

The next example demonstrates that as long as a strong reference to an object exists, the WeakReference shows that the object is alive. When there are no more strong references, the WeakReference shows that it’s no longer alive.

object obj = new object(); WeakReference weak = new WeakReference(obj); GC.Collect(); Console.WriteLine("IsAlive: {0} obj!=null is {1}", weak.IsAlive,obj!=null); obj = null; GC.Collect(); Console.WriteLine("IsAlive: {0}", weak.IsAlive);

This is the output you’ll see when running the example:

IsAlive: True obj!=null is True IsAlive: False

You can use WeakReference to make the subscription of the observer weak as well, so if the only thing that keeps the observer alive is observable, it won’t prevent the GC from reclaiming it. I call this pattern the weak observer.

Figure 11.9 illustrates what you’re trying to achieve. The idea here is to create a proxy object that holds a weak reference to the observer and delegates the calls from the source observable to the observer. In order for the proxy to receive the notifications from the observable, it must implement the IObserver<T> interface.

Figure 11.9. Disconnecting the observable and its observer with a mediator observer that weakly references the real observer

For each notification the WeakObserverProxy receives from the observable, it checks whether the object is still alive and isn’t reclaimed by the GC. If so, it will pass the notification to it. If the observer has already been reclaimed, WeakObserverProxy disposes of the subscription to the source observable.

Here’s an example of how this looks for the OnNext method:

IObserver<T> observer; if (_weakObserver.TryGetTarget(out observer)) { observer.OnNext(value); } else { _subscriptionToSource.Dispose(); }

The OnError and OnCompleted methods will do the same thing, so I refactored my code into this:

void NotifyObserver(Action<IObserver<T>> action) { IObserver<T> observer; if (_weakObserver.TryGetTarget(out observer)) { action(observer); } else { _subscriptionToSource.Dispose(); } } public void OnNext(T value) { NotifyObserver(observer=>observer.OnNext(value)); }

Besides the fact that the inner observer might get collected, the user can dispose of the subscription at any time. The WeakObserverProxy object holds the subscription object to the source observable and exposes it through the AsDisposable method. The exposed disposable is then returned to the client code that subscribes to the observable.

This is the complete code for the WeakObserverProxy.

Listing 11.2. The WeakObserverProxy

class WeakObserverProxy<T>:IObserver<T> { private IDisposable _subscriptionToSource; private WeakReference<IObserver<T>> _weakObserver; public WeakObserverProxy(IObserver<T> observer) { _weakObserver = new WeakReference<IObserver<T>>(observer); } internal void SetSubscription(IDisposable subscriptionToSource) { _subscriptionToSource = subscriptionToSource; } void NotifyObserver(Action<IObserver<T>> action) { IObserver<T> observer; if (_weakObserver.TryGetTarget(out observer)) { action(observer); } else { _subscriptionToSource.Dispose(); } } public void OnNext(T value) { NotifyObserver(observer=>observer.OnNext(value)); } public void OnError(Exception error) { NotifyObserver(observer => observer.OnError(error)); } public void OnCompleted() { NotifyObserver(observer => observer.OnCompleted()); } public IDisposable AsDisposable() { return _subscriptionToSource; } }

To make your life easier, I created the extension method AsWeakObservable that will wrap any observable that you want to subscribe to weakly.

Now, when the observer subscribes, a WeakObserverProxy is created, and the observer and the subscription to the source observable are passed to it. Finally, you return the inner subscription to the caller:

public static IObservable<T> AsWeakObservable<T>(this IObservable<T> source) { return Observable.Create<T>(o => { var weakObserverProxy = new WeakObserverProxy<T>(o); var subscription = source.Subscribe(weakObserverProxy); weakObserverProxy.SetSubscription(subscription); return weakObserverProxy.AsDisposable();; }); }

Here’s an example to test that the weak observer works. In the following code, you create an observable that emits a notification each second (like a sensor that reports the measurement it takes), and weakly subscribes an observer to it. The program holds the subscription for 2 seconds in order to keep the observer alive. Then you remove the reference to the subscription object (setting it to null) and force a GC. Afterward, no more notifications are emitted even though you haven’t called the Dispose method explicitly:

var subscription = Observable.Interval(TimeSpan.FromSeconds(1)) .AsWeakObservable() .SubscribeConsole("Interval"); Console.WriteLine("Collecting"); GC.Collect(); Thread.Sleep(2000); //2 seconds GC.KeepAlive(subscription); Console.WriteLine("Done sleeping"); Console.WriteLine("Collecting"); subscription = null; GC.Collect(); Thread.Sleep(2000); //2 seconds Console.WriteLine("Done sleeping");

This is my output after running the program:

Collecting Interval - OnNext(0) Interval - OnNext(1) Done sleeping Collecting Done sleeping

From the output, you can see that while the subscription is held by a strong reference, notifications keep on coming. When there are no more strong references that are roots to the underlying observer, the notifications stop.

Using weak observers isn’t something you should do on a regular basis (just as with weak events), because in most cases you want to be in control of the subscription. But if you find yourself unable to deterministically predict the lifespan of an observer (with the Windows Store application’s backstack, for example), then a weak observer is a strong utility to make your life easier and level your application resource usage.

You need to remember that the WeakObserverProxy object might stay alive for a long time after the observer it references is collected. This is because when the observable emits a notification, the WeakObserverProxy can check whether it’s still needed, and if not, it can unsubscribe itself from the observable.

Next, you’ll dive into another situation where the consumption of resources in your application increases even though nothing is wrong with the code you write. This might occur when the number of notifications an observer receives per time frame is large. This is called backpressure.

11.3. Dealing with backpressure

The observable provides an abstraction over the source of the notifications that emits them, and nothing in the observable interface provides any clue about the rate at which those notifications are emitted.

11.3.1. Observables of different rates

There are three possible outcomes regarding the rate of processing done by the observer; these are illustrated in figure 11.10:

- The observer processes the notifications at the same rate as the observable emits them.

- The observable is faster than the observer. This is a case of overload.

- The observer is faster than the observable. In this case, the observer can process more notifications per time frame than what is emitted by the observable.

Figure 11.10. The effect of different rates between an observable and an observer

You can compare those situations to a website that gets requests from clients. The web server that hosts the website can handle a limited number of requests. When the number of requests is too high, you might get an error that says the website isn’t available, as shown in figure 11.11.

Figure 11.11. A Service Unavailable error page that you might get when the website is overloaded

For cases 1 and 3, where the observer is just as fast as or faster than the observable, no problems will arise and the system will work great. But when the rate of the observable becomes greater than the ability of the observer to consume the notifications, you’re on the road to an overload that will eventually crash your system, unless you slow things down in some way.

As stated previously, we call this kind of overload backpressure, and it’s something that’s easy to get into, as the next example shows.

Note

Backpressure is also defined as the ability to tell a source to slow down in order to prevent flooding.

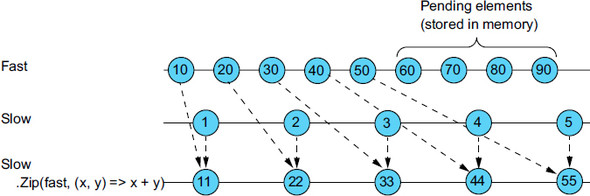

In the following example, you use the Zip operator to combine an observable that emits a notification each second with another observable that emits a notification every 2 seconds. These observables might emit notifications from two sensors or from two remote servers, but in any case, the result will be that the slow observable notifications will be buffered by the Zip operator:

var fast = Observable.Interval(TimeSpan.FromSeconds(1)); var slow = Observable.Interval(TimeSpan.FromSeconds(2)); var zipped = slow.Zip(fast, (x, y) => x + y);

The Zip operator combines the elements based on their ordinal position, so it must store the elements from the fast observable until the corresponding items are emitted by the slow observable. After 10 seconds, the fast observable emits 10 elements, and the slow observable emits only 5, so the Zip operator currently contains only 5 elements in memory. If you run this example for a full day (total time of 86,400 seconds), you’ll have 43,200 elements in memory. An illustration of the problem is shown in figure 11.12.

Figure 11.12. Zipping a fast observable with a slow observable leads to pending elements stored in memory.

Now that we’ve established what backpressure is, we can discuss ways to deal with it.

11.3.2. Mitigating backpressure

Imagine someone is throwing balls at you at a high rate of speed, and you need to catch them and organize them on a shelf. You have three possible ways to handle this:

- Ignore some of the balls and let them drop (the lossy approach).

- Temporarily put some of the balls in a box and get them later (the lossless approach).

- Signal the thrower to slow down until you’re free to catch the balls (the controlled lossless approach).

Some Rx operators take the lossy approach and some take the lossless, but none of them take the controlled lossless approach.

Tip

Reactive Streams (www.reactive-streams.org/) tries to provide a controlled lossless approach to observables. As stated on the Reactive Streams website, this initiative provides a standard for asynchronous stream processing with nonblocking backpressure (controlled lossless). This standard extends the Rx model to allow the observer to notify the observable about the load it can take. Reactive Streams is not supported by Rx.NET at the time of this writing.

Lossy approach

Say you have two sensors that emit notifications. One emits twice as fast as the second, and you need to combine the notifications. You need to consider whether the notification emitted by the slower sensor is still relevant. If the sensor emits heart rate, ask yourself whether the heart that was measured an hour ago is still relevant. Is it better to drop it and use only the latest one? In cases like these, where dropping a message is reasonable, here’s a list of the options you can take:

- If you’re combining observables, but it’s sufficient to combine only the latest emitted notification from each of them, use the CombineLatest operator (chapter 9).

- If the rate of the observable is high at times, and a notification is irrelevant if another one comes in a short while, use the Throttle operator (chapter 10).

- If you need to consume the notifications at a steady pace, no matter how many notifications are emitted in each fragment of time, use the Scan operator (chapter 10).

If you need to combine notifications coming from a heart-rate monitor with notifications coming from a speedometer, and there’s a chance that the heart-rate monitor produces values faster than the speedometer, this is how you’ll overcome backpressure with the CombineLatest operator:

heartRates.CombineLatest(speeds, (h, s) => String.Format("Heart:{0} Speed:{1}", h, s))

In all of the lossy approach options, you’ll lose some notifications in favor of lower resource consumption, and this is ideal if being responsive and available is your highest priority. When your priority is in consuming each of the notifications emitted, you need to take the lossless approach.

Lossless approach

Say an observable is emitting text messages that you need to display onscreen. Every time a change is made to the screen, it needs to refresh itself, which takes time. When the rate of messages is high, the screen refreshes can cause the UI to be unresponsive and make the user unhappy. A better solution would be to refresh the screen with bulk messages instead of doing it one a time. In such scenarios, you can’t drop messages just because they come in at a high rate. Therefore, you need a lossless approach to handle the backpressure. The lossless approach that Rx supports is through buffering, whereby items are stored and then processed as a bulk operation.

The Buffer operator you learned about in chapter 9 lets you specify the buffer period by time or amount. This should be handled with care; otherwise, the memory consumption of your application will increase and possibly crash your application.

11.4. Summary

In this final chapter, you looked at methods for optimizing your Rx code. You saw how to react to errors in a graceful manner and how to control the resources your code uses.

- The Catch operator lets you react to a specific type of exception that’s thrown in the observable pipeline. It sets a fallback observable that the observer will be subscribed to in case an exception is thrown.

- The OnErrorResumeNext operator concatenates the observable to another for both successful completion and error termination.

- The Retry operator resubscribes the observer to the observable in the case of error.

- The Using operator deterministically disposes of an object in case the observable terminates. This way, resources used inside the observable pipeline can be properly cleaned.

- The Finally operator runs specific code (like cleanup or logging) in case the observable terminates. This way, you can run cleanup code at the end of the observable processing.

- The observable holds a strong reference to the observers, which can cause the observers to stay alive longer than they should (dangling observers).

- WeakObservers change the reference that’s used to hold the observer into a WeakReference, eliminating cases in which an observer isn’t collected because an observable holds it.

- Backpressure occurs when a consumer is slower than the producer.

- Backpressure can cause system performance to degrade, both in memory and throughput.

- The CombineLatest, Throttle, and Scan operators handle backpressure with a lossy approach; some notifications are dropped in favor of lower resource consumption.

- The Buffer operator handles backpressure by saving the notifications into a bulk operation that can then be processed as a whole.