Welcome! The purpose of this chapter is to tackle some of the most common PHP security myths head-on. The last thing we want is for novice PHP programmers to get a false sense of security because they obfuscate their filenames or directory structure. Those tricks simply don’t work against hackers who have plenty of time and computer resources. The chapter will focus on five common myths.

If you’re reading this, we know two things about you: First, you write PHP applications that run online. Second, you’re not a hard-core security guru. In fact, you’re probably holding this book right now because other security books left you with more questions than you started with, or because this is the first time you’ve really thought about securing your applications.

Add to that the fact that we are writing insecure applications in PHP, a language that is inherently insecure. It doesn’t have strongly typed variables, it utilizes global variables, and users can make function calls through the browser. Many programmers consider these to be features of PHP, not liabilities, but we’re examining Web applications from a security standpoint, not from a convenience or functional standpoint.

Our goal in writing this book is to give you the tools you need to make your applications more secure. By their nature, Web applications are inherently insecure. You are allowing unknown users to have direct access to your server. Even if you have a firewall, you have to poke a hole in it to allow your Web application to be accessible to the outside world. These are not security-minded actions.

If you want a truly secure application, don’t connect it to the Web. If you want to truly secure PHP code, write a wrapper that sits between PHP and everything else, keeping it safe. The Hardened-PHP Group is working on this type of wrapper, but we’ll get to that in Chapter 13, “Securing PHP on the Server.”

All we are trying to do—all we can do—is make it harder for malicious users to attack our applications. We can never create truly secure code, but we can write code that is secure enough. The good news is that most hackers are fundamentally lazy. If our applications are reasonably secure, the vast majority of hackers will leave them alone because there are plenty of easier targets. We don’t need to run faster than the bad guys; we just need to run faster than the pack so they will pick an easier target.

There are a few points to keep in mind as we try to outrun the pack.

First, security in depth is key. Never rely on just one method of protecting your applications. If that one method is compromised, you’re out of luck. A multilayered approach to security, one that involves your server, network, code, files, database, users, etc., will mitigate compromises in any one level. In this book, we focus mainly on the code, touching lightly on the rest. Out in the field you may not have control over some of the other aspects, such as server security, but you can keep depth in mind and insist on knowing what security measures your vendors, such as your Web hosting company, have implemented.

The second point to remember is one that will keep you sane in any aspect of IT: Assume everyone else you deal with is either incompetent or malicious; never fully trust the security and error-handling measure that is handed to you by other programmers, other applications, etc. This sounds harsh, but in the world of Internet security, you have to be a little bit paranoid. Trust in the basic goodness of humanity later. While you’re securing a Web application, trust no one—especially your users and the data they send you. Verify every scrap of data that goes into or out of your application, regardless of its source. You can never know if other code has a hole in it or not (remember, Web applications are inherently insecure), so verify that data looks the way your application expects it to look before you act on it.

Finally, let’s get our terms straight. Throughout this book we’ve used the term hacker to refer to malicious users whose goal is to break into or crash Web servers and otherwise make life difficult for the rest of us. There are some who will object to this usage because the word hacker also refers to anyone who digs into the guts of a system (whether it’s a server, an application, or the cable box) to see how it works and to improve upon it. If you prefer that usage, feel free to mentally substitute cracker for hacker throughout the book. Since the point of this book is to introduce security concepts to those who have no prior experience, we chose to use the term that the widest possible audience would immediately understand. Let’s not get bogged down in terminology when there are bad guys out there right now who don’t care what we call them as long as we leave our applications nice and insecure.

One of the most common misconceptions surrounding application security is that keeping the Web server secure is the job of the system administrator, not the application programmer. In reality, keeping hackers at bay is the responsibility of everyone involved with the server. The purpose of this book is to demonstrate two crucial points to application programmers:

• Hackers usually gain control of servers through holes created by insecure applications.

• Application programmers can close the holes in their applications without dropping everything to earn a degree in computer science.

System administrators do have a role in securing the Web server, and if you happen to wear both the system administration and application programming hats, be sure to read Chapter 13, “Securing PHP on the Server.” The rest of the book, however, is devoted to the ways that hackers exploit insecure applications and how you can be sure that yours isn’t one of them.

Some hackers do attack servers and networks directly, but most search for insecure applications running on those servers and use them as a gateway to the server and network. Why do they focus on applications, rather than the true targets—servers and networks? They target applications because those are often the weakest parts of the system.

Physical security and the network protect the server itself. The network is protected by a firewall. But the applications running on the server are often an open door that bypasses both physical and network security, as shown in Figure 1.1.

That’s why hackers target applications—they’re a lot easier to break into than either the physical server room or most networks. Securing the server room can be as simple as installing a good deadbolt lock on the front door of the building. You can get more complex locks, but a simple deadbolt will give you a reasonable level of physical security. Networks are similar—as long as you have a firewall and perhaps an intrusion detection system running, you have a reasonably secure network. Security at the application level requires that the programs running on the server be designed with security in mind. That’s the purpose of this book—to give application programmers the tools and knowledge they need to harden their own applications, one step at a time.

As with most topics in the world of information technology, security has a reputation for being difficult, complicated, and better left to experts with a dozen certifications, a Ph.D. in computer science, and 20 years of experience in the field. Once you understand the basics, you’ll find that most security concepts really aren’t as difficult as they seemed at first. There are times to call in a security guru, but you don’t need to be an expert to significantly improve the security of your own application. This book distills the information you really need to harden your application, and it gives you a solid understanding of basic application security concepts.

Before we get into specific security techniques, let’s take a moment to examine why you need to understand security. As soon as you release your application to the public—even if yours is the only server it ever runs on—you’re a target for hackers. Even a fairly simple application you write for your own personal use is a potential opening for hackers. Having said that, hackers aren’t necessarily smarter or more highly trained than the average programmer. What they do have is a lot of time on their hands and a desire to test themselves against system administrators and application programmers. As soon as your code is run on a public server, you should assume that a hacker will eventually find it and attempt to break it. It may take years, or you could see the first attempts within days, depending on how attractive your server is to the hacker and how obvious the security holes are.

Does this mean you should give up trying to keep hackers out of your code? Of course not. Security breaches aren’t inevitable. They’re so common because most programmers don’t understand the basic methods for securing an application. Once you’ve read this book, you’ll have all the tools you need to make your application more secure than most. Hackers focus their energies on the easiest targets, and you’re taking the first steps to make sure they pass by your application. Don’t worry; all the techniques you’ll learn here are fairly simple and easy, but they make a big difference in the security of your application.

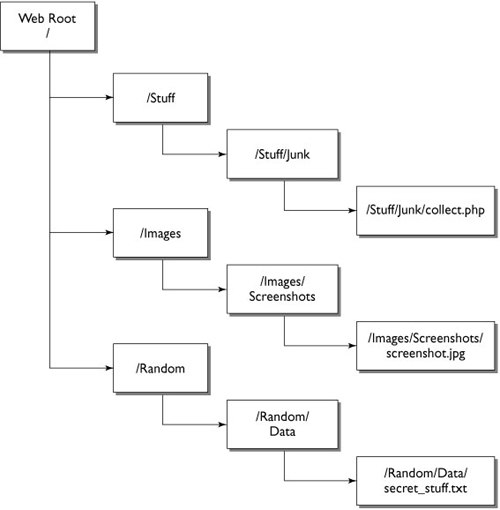

Some programmers create complicated directory structures and files with random, meaningless names in the hope of confusing hackers. Unfortunately, because of the way hackers operate, obfuscating filenames and hiding them in complicated directory structures really doesn’t work. This strategy does make your code difficult to maintain and update, but that’s about it.

Most hackers don’t personally dig through your application code looking for signs of a vulnerability. They’re fundamentally lazy (in a good way). Rather than doing the long and tedious work of finding vulnerable applications themselves, they write scripts to dig through application code for them. With plenty of CPU cycles and time to burn, eventually those scripts will find their way through the most complex directory structure, as shown in Figure 1.2.

Having said that, there is a place for security through obfuscation, if it is part of a larger, more in-depth security plan. William worked with a system administrator in the 1990s who made very good use of the concept of security through obfuscation. He created a false login screen for the server, making it look as if the server were running one operating system when it was really running something else entirely.

It was an interesting idea, and it did provide some measure of security because when hackers attempted to break in, they were looking for common vulnerabilities in the fake OS rather than targeting the true OS.

You can use the same technique to provide a layer of security in your application. For example, rather than calling your files *.php, you can call them *.html. No one will be fooled into thinking that your application is pure HTML, but at least you aren’t announcing to the world what language the program is written in. Simply changing the filenames does nothing to actually secure your program, but it does make the hacker work a little harder to find the vulnerabilities. Just don’t forget to tell the Web server to send your .html files through the PHP interpreter before serving them up to the user.

In the end, securing your application by hiding important configuration files (such as the one that holds your database connection information) and changing filenames doesn’t hurt anything, but don’t rely on this method alone to keep hackers out of your code.

PHP’s native session management capabilities give application programmers some tools to create a secure session environment, but they don’t automatically protect your application against session hijacking, fixation, or poisoning, any more than simply owning a fire extinguisher protects your home from fire.

Sessions are widely used in modern Web applications to store everything from authentication information to browsing history, and often they’re used by programmers with only a cursory understanding of them. This makes them a natural target for hackers.

In Chapter 9, “Session Security,” we go over three types of session attacks and show you how to defend against them.

Every day, hackers target minor applications. Why? Because they’re easier targets than bigger, better-known applications. Small, relatively obscure applications—like yours, perhaps?—are easier to break because they are usually written by a single individual with little or no formal security training or access to code reviews and penetration testing facilities.

This fact—that small applications are so often the targets of hacker attacks—is the very reason we wrote this book. When we owned a small Web hosting company, several of our clients used a variant of OptionCart, an e-commerce application designed for small Web-based retailers. The particular variation we worked with was not that widely used, but for a few weeks it was at the top of the charts—specifically the CERT security advisories. CERT is the Computer Emergency Response Team based at Carnegie Mellon University. It is one of the security watchdogs on the Internet, and it publishes regular reports of compromised servers, networks, and applications. You do not want your application to gain fame through CERT! We worked with the developer of OptionCart to close several security holes in the application and have expanded on the advice we gave her to create this book.

There’s one last idea to tackle before we get down to the business of securing Web applications: the idea that as long as you have strong network security, you don’t have to worry about securing each and every application that runs on the server. After all, if nobody can hack into the network, then nobody can get to the applications, right?

Wrong! This is especially true of a Web server, which has to be open to the public in order to serve Web sites.

On a server, every single application, from the operating system to the Web server to individual Web applications, is a point of entry. One vulnerability in one application can give a hacker control of the entire server—and the rest of the servers on the network as well.

Let’s assume for a moment that your network is completely secure. There’s only one point of entry, and it’s protected by a firewall that’s locked up tight. Only authorized users can access the resources behind the firewall.

What happens when one of those authorized users loses his or her temper? We worked with a company that spared no expense to create the most perfectly secure network possible—only to have it compromised within weeks when the system administrator quit and left a Trojan horse behind. There was nothing wrong with the security of the network, except that the guy holding the keys to the gate wasn’t as trustworthy as everyone assumed he was. He had full access to the network after he left the company, and he compromised every server within hours. The good news was, the network remained secure. Unfortunately, having a secure network doesn’t do any good if the servers on the network are wide open. Even securing the servers doesn’t guarantee that hackers will be kept out of the data stored on those servers, because hackers can gain legitimate access to server resources through insecure applications.

The point here is to avoid having a single point of failure; if the network is compromised, everything is exposed to attack. If a server is compromised, the data stored on the server is vulnerable. If an application is insecure, even a secured server can be taken over. The better way to secure any system is a three-pronged defense: Secure the network, secure the server, and secure every application. This way, even if one of the three parts of the equation is compromised, the other two should withstand the attack.

We’ve given you some food for thought in this chapter and convinced you, we hope, that although outwitting hackers isn’t impossible, it’s also not something that “just happens.” The rest of this book gives you the tools and step-by-step information you need to secure your application against attack.