Chapter 4

Service Science Fundamentals

At the end of the day, the cocreated total value of a service lies in its ability to satisfy the needs of its provider-side and customer-side people. Hence, the resource, operations, and management models of service systems should be centered on the end users. From the discussions in the preceding chapters, it is understood that both service providers and customers are the core elements that constitute a service system, cocreating services by transforming the customers' needs with the support of infrastructural, financial, social, and natural resources. Even though in a solely self-service system, we are frequently personifying its serving units and processes to improve our service effectiveness and customer satisfaction. For instance, personifying allows a service provider to have empathic and pleasing considerations in service provision to enrich personal touches. As a result, the service provider can avoid creating apathy and negativity that people might feel when physical machines are only present in carrying on certain service encounters from the service provider side at a given time.

As compared to manufacturing that has been mainly centered with physical matters, services are people-centered. Because the resources in service systems, largely people, cannot be held. It becomes extremely challenging for us to model the dynamics of service systems. We understand that people participating in service production and consumption have physiological and psychological characteristics, cognitive ability, and sociological constraints (Dietrich and Harrison, (2006). People's behaviors are extremely difficult to model in general. As a result, when we compare studies between services and manufacturing in the literature, we can easily find that there generally lacks quantitative modeling of the dynamics of service systems although the literature has a long history of publishing empirical studies or qualitative research of services or service systems in focused areas, including service market, operations, and management.

As discussed in the previous chapters, we must use service-dominant thinking to explore the people-centric and systemic interactions and their impacts on the dynamics of service systems. Bearing in mind that real-time quantitative explorations of service systems are the ultimate goal in the service research community, we know that an applicable approach must be process-driven, people-centric, holistic, and computational. Undoubtedly, Service Science as metascience of services must build on predecessors' excellent work from many traditional disciplines. Like scores of other constituent parts of the study of services, Service Science must follow the scientific method and must be rigorous and scholarly. Service Science must be built upon combining the best of a variety of perspectives into an integrated and interdisciplinary discovery and analytics of service systems (Larson, (2011); Qiu, (2012).

Because the laws of service radically are a set of rules and guidelines, we can apply them to founding and fostering further scientific explorations in the field of service engineering and management. In this chapter, we first explore Service Science fundamentals, focusing on finding the laws of service in general. By referring to Newton's law of motion that explains and investigates the dynamics of physical objects and systems, we articulate that a similar set of principles can be deducted from the dynamics of service. Secondly, we discuss that service-encounter-based sociophysics wins a focus on the formed service encounter networks to explain and investigate the dynamics of service systems. Then, we present an overview of Service Science in a sociophysics perspective. Finally, a brief conclusion will be provided, highlighting the potential of Service Science in general.

4.1 The Fundamental Laws of Service: A Systemic Viewpoint

“If we don't know what the laws of service are, or we think they don't matter, and thus continually break them, we will pay the consequences.” “Without knowing the laws of service and how they impact our business, we will most surely fall into chaos, lose our competitive edge and cease to be profitable” (Meany, (2012). Many scholars and practitioners (Wyckoff and Maister, (2005) have attempted to put together a system of rules and guidelines as service laws, aimed at identifying managerial and operational guidance with scientific rigor for service organizations so as to help them achieve effective service marketing, management, and operations in practice.

For instance, Meany (2012) compiles the following seven real, concrete service laws that could assist service organizations to establish managerial guidelines in cultivating their business operations:

- The Law of Customers. “Treat everyone around you like a customer, or someone else will.”

- The Law of Consistency. “Don't just make it a priority … keep it a priority.”

- The Law of Expectation. “If you are going to assume anything, assume customer loyalty.”

- The Law of Challenge. “Good customer communication means bridging service gaps, not falling into them.”

- The Law of Control. “If your house is in order, your customer's house is in order.”

- The Law of Image. “Nobody knows where the beef is without the sizzle.”

- The Law of The Basics. “First things first, second things not at all.”

In theory, the provided effective guidance helps service organizations improve their competitiveness and profitability so as to enjoy long-term success in their respective industries.

In general, law is a system of rules and guidelines that are enforced to control and govern social behavior. There are varieties of laws and regulations. The discussions on the distinctions of public and private laws, nationally and internationally, are certainly beyond the scope of this book. As we are interested in the rules and guidelines that can be applied to service engineering and management in general, we essentially focus on finding the principles that can scientifically guide us to enable and govern service offerings in a repeatable, competitive, and profitable manner. According to the Oxford English dictionary (Oxford, (2001), a physical law or scientific law in the physical world is “a theoretical principle deduced from particular facts, applicable to a defined group or class of phenomena, and expressible by the statement that a particular phenomenon always occurs if certain conditions be present.”

Before we fully delve into the compilation of the fundamental laws of service, we can briefly illustrate the similarity and dissimilarity between the motion of a physical object and the user experience perceived from a service. In physics, the action and reaction between two objects define how these two objects interact. Similarly, the action (or request) and reaction (or response) in cocreating the benefits of the service then define how service provider-side and customer-side people execute the essential social and transactional interaction within the process of transformation of the needs of customers. Furthermore, the motion state change of a physical object is due to the fact that there is an external force applied to the object. Similarly, the change of user experience perceived from a service is due to the fact that there is an extra effort applied to the service. However, an exact relationship between force, mass, and acceleration can be defined for the motion of a physical object. The perceived user experience holds a similar measure but is mainly subjective in nature. Hence, we must look into these challenges next in a comprehensive manner.

4.1.1 Newton's Three Laws of Motion

An excellent example of physical laws is Newton's three laws of motion. According to Wikipedia (NewtonWiki, (2013), the three laws of motion have been used to explain and investigate the motion of many physical objects and systems over three centuries. The three laws of motion are fundamental in Physics, which were first compiled by Sir Isaac Newton in his book Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica. The book was written in Latin; its first edition was published in 1687. Newton's three laws are useful approximations at the scales and speeds of daily life, in which physical objects move at the much slower speed than light. It is well recognized that the combination of Newton's laws of motion, his universal law of gravitation, and calculus provided a unified quantitative explanation for a wide range of physical phenomena over three centuries.

Newton's first law is well known as the law of inertia. “If there is no net force on an object, then its velocity is constant. The object is either at rest (if its velocity is equal to zero), or it moves with constant speed in a single direction” (NewtonWiki, (2013). This simply means that there is a natural tendency of an object to keep on doing what the object is doing. An object resists a change in its state of motion, at rest or moving at a constant velocity. “Changes in motion must be imposed against the tendency of an object to retain its state of motion. In the absence of net forces, a moving object tends to move along a straight line path indefinitely” (NewtonWiki, (2013).

Newton's second law states an exact relationship between force, mass, and acceleration. “The acceleration ![]() of a body is parallel and directly proportional to the net force

of a body is parallel and directly proportional to the net force ![]() acting on the body, is in the direction of the net force, and is inversely proportional to the mass

acting on the body, is in the direction of the net force, and is inversely proportional to the mass ![]() of the body, i.e.,

of the body, i.e., ![]() ” (NewtonWiki, (2013). Simply put, if an object is accelerating, then there is a force on it. “Consistent with the first law, the time derivative of the momentum is non-zero when the momentum changes direction, even if there is no change in its magnitude; such is the case with uniform circular motion. The relationship also implies the conservation of momentum: when the net force on the body is zero, the momentum of the body is constant. Any net force is equal to the rate of change of the momentum” (NewtonWiki, (2013).

” (NewtonWiki, (2013). Simply put, if an object is accelerating, then there is a force on it. “Consistent with the first law, the time derivative of the momentum is non-zero when the momentum changes direction, even if there is no change in its magnitude; such is the case with uniform circular motion. The relationship also implies the conservation of momentum: when the net force on the body is zero, the momentum of the body is constant. Any net force is equal to the rate of change of the momentum” (NewtonWiki, (2013).

Newton's third law is well known as the law of action–reaction. “When a first body exerts a force ![]() on a second body, the second body simultaneously exerts a force

on a second body, the second body simultaneously exerts a force ![]() =

= ![]() on the first body. This means that

on the first body. This means that ![]() and

and ![]() are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction” (NewtonWiki, (2013). The third law essentially defines how different objects interact. “The action and the reaction are simultaneous, and it does not matter which is called the action and which is called reaction; both forces are part of a single interaction, and neither force exists without the other” (NewtonWiki, (2013).

are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction” (NewtonWiki, (2013). The third law essentially defines how different objects interact. “The action and the reaction are simultaneous, and it does not matter which is called the action and which is called reaction; both forces are part of a single interaction, and neither force exists without the other” (NewtonWiki, (2013).

We understand that the three laws of motion have been used to explain and investigate the motion of physical objects and systems over three centuries although they have never been proved in a scientific way. We adopt the same approach in this book. By referring to Newton's law of motion that explain and investigate the dynamics of physical objects and systems, we radically advocate that a similar set of principles can be compiled for exploring the dynamics of service encounter networks. With the help of derived theoretical foundations, ultimately we can apply approximations of systems behavior to explain and investigate the overall dynamics of service systems.

4.1.2 The Three Fundamental Laws of Service: The Newtonian Approach

Before we discuss the three fundamental laws of service, let us review the definition of service we had in Chapter 2. Service is considered as a transformation process in which both provider-side and customer-side people participate in an interactive manner, applying relevant knowledge, skills, and experiences in order to cocreate mutual benefits for the service providers and their customers. Technically and socioeconomically the transformation process encompasses a series of service encounters that can be direct or indirect, consecutive or intermittent, physical or virtual, and brief or intensive. The value of service depends on the sociotechnical efficacy and effectiveness of all of the service encounters experienced throughout the service lifecycle.

Without question, the interactions between service providers and customers are the key to the services performed by the service providers and their customers. In a simple service interaction, two entities, a provider and a customer, are exactly the same as the physical objects in the above-discussed Newton's interpretation. Each interaction requires an effort from each of the entities and creates an impact on the entities. Thus, it is the interaction that generates a service experience perceived by the two entities in our sociotechnical service world. In other words, the effort generating the service experience in Service Science is our “force” that is similar to the force that changes the motion of an object in Physics.

In the physical world, mass, acceleration, momentum, and force are assumed to be externally defined quantities. Newton's three laws of motion describe how force, mass, acceleration, and momentum are related in a quantitative manner. If a service system's systemic mass, acceleration, momentum, and effort in our sociotechnical service world can also be assumed to be externally defined quantities, we can try to form a similar interpretation describing the laws of service.

As discussed earlier, Newton's three laws are fundamental to physical objects, essentially describing basic rules about how the motion of physical objects changes. The question we ask here is what the fundamental laws of service are. As a force applied to an object changes the motion of the object, effort that is viewed as a sociotechnical force changes the experience perceived by a participant or entity. As an analogy to Newton's three laws, the fundamental laws of service must be the ones that can be applied to describe the basic rules about how the experience of a service perceived by a participant changes. Here is our first attempt to compile the laws of service from this discussion:

- Service's First Law. If there is no changing effort on a service, then the service experience perceived by an entity remains the same.

- Service's Second Law. The acceleration

of an entity is directly proportional to the changed effort

of an entity is directly proportional to the changed effort  applying to the entity, is in the direction of the changed effort, and is inversely proportional to the systemic mass

applying to the entity, is in the direction of the changed effort, and is inversely proportional to the systemic mass  of the entity, that is,

of the entity, that is,  .

. - Service's Third Law. When a first entity applies an effort

on a second entity, the second entity simultaneously applies an effort

on a second entity, the second entity simultaneously applies an effort  on the first entity. This means that

on the first entity. This means that  and

and  are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction.

are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction.

Just like Newton's first law, the first law of service aims to establish a general frame of reference for which the other service laws are applicable. In the sociotechnical service world, services are always cocreated by service providers and customers. An entity that is defined in the laws of service thus is either a human being or personalized system. At each point of customer interaction, a customer gains experience that essentially is the perceived effect of the fulfillments in both the utilitarian and sociopsychological dimensions. Therefore, to an end user, the experience perceived by the end user is what a service is all about.

Here are some real-life examples of services, which help us interpret the practical meaning of the above-compiled laws of service. A guest who stayed in a hotel in a city for 3 days had his/her unique experience. Assume that the hotel has applied no changing effort to the provided service. If the guest would stay there for another 3 days, he/she realistically should perceive the same experience he/she perceived before. Similarly, a group of students as customers took a course that was offered by a professor in Lion's College. They surely had their learning experience. Assume that Lion's College made no changing effort on offering the course, including classroom equipment, instructions, and other related learning supports. If another group of students with a similar background that the first group of students had would take the course in a new semester, the second group students should also perceive the same experience that the first group of students perceived earlier. We understand that each service might have its unique value measured in certain utilitarian and sociopsychological dimensions. However, the established reference frame for services remains the same.

Service's second law aims to define how a changing effort on a service makes a difference in a quantitative manner. In reality, we know that “the only constant in the universe is change” is well applied to today's business world. Indeed, during the period of time when a customer consumes a service, the service provider can make a variety of changes in order to meet the customer's changing needs in both the utilitarian and sociopsychological dimensions.

Let us continue to use the above-discussed hotel and learning services as examples. The guest who stayed in the hotel for 3 days at the second time actually had a morning meeting in an organization that is located 10 miles away from the hotel. Assume that he/she was not familiar with the city and the hotel does not provide shuttle services. Because the hotel cannot provide shuttle services to its customers, the hotel would like to help him/her arrange a taxi. His/her experience on his/her second stay in the hotel might be positively impacted because of the additional help provided by the hotel. As for the Lion's College case, changing efforts could include enhanced lectures from the professor, a newly equipped classroom, and/or more experienced teaching assistants. As a result, the second group students could perceive much better experience than what the first group of students perceived earlier.

With respect to the established frame of reference, the acceleration ![]() of an entity defined in the second law of service is directly proportional to the changed effort

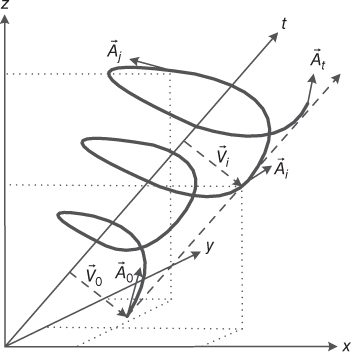

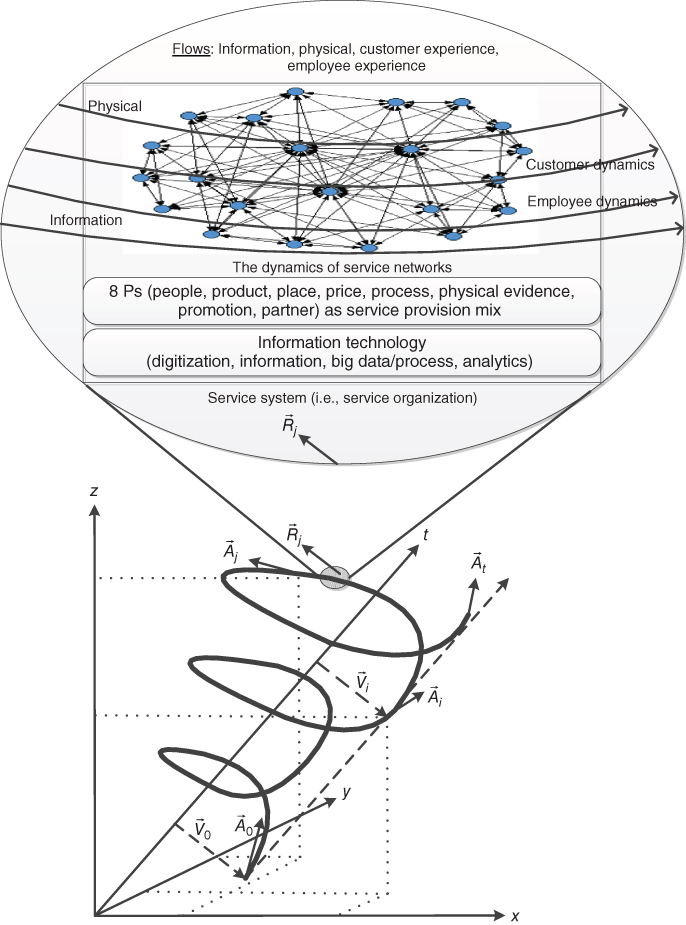

of an entity defined in the second law of service is directly proportional to the changed effort ![]() applied to the entity. An illustration of the momentum of service based on the second law of service is shown in Figure 4.1. In reality, when a given changing effort

applied to the entity. An illustration of the momentum of service based on the second law of service is shown in Figure 4.1. In reality, when a given changing effort ![]() is applied to a small and simple entity with a systemic mass of

is applied to a small and simple entity with a systemic mass of ![]() , we assume that the corresponding acceleration of service dynamics can be quantified as

, we assume that the corresponding acceleration of service dynamics can be quantified as ![]() ; when the same changing effort

; when the same changing effort ![]() is applied to a large and complex entity with a systemic mass of

is applied to a large and complex entity with a systemic mass of ![]() , we assume that the corresponding acceleration of service dynamics can be quantified as

, we assume that the corresponding acceleration of service dynamics can be quantified as ![]() . We know that

. We know that ![]() <

< ![]() holds for sure. In other words, the smaller and less complex an entity to which a changing effort is applied, the more significant the resultant impact is. However, in the sociotechnical service world, it is unnecessary that

holds for sure. In other words, the smaller and less complex an entity to which a changing effort is applied, the more significant the resultant impact is. However, in the sociotechnical service world, it is unnecessary that ![]() is more beneficial than

is more beneficial than ![]() in light of realizing the business goal.

in light of realizing the business goal.

Figure 4.1 An illustration of the momentum of service based on the laws of service.

Service's third law can also be called the mutuality law, defining the equality of efforts made, respectively, by interacting entities during service provision. A good and classical example can be “a bushel of wheat exchanged for a barrel of oil” between two entities that was discussed in Chapter 1. The first entity applies an effort ![]() on growing a bushel of wheat, while the second entity must apply the same amount of effort

on growing a bushel of wheat, while the second entity must apply the same amount of effort ![]() on making a barrel of oil. It is easy to understand the real meaning of the mutuality law if we apply modern economics here. To the first entity, an effort of

on making a barrel of oil. It is easy to understand the real meaning of the mutuality law if we apply modern economics here. To the first entity, an effort of ![]() is made to exchange for an equal effort

is made to exchange for an equal effort ![]() made by the second entity. Because of an effort made by the interacting entity, its direction must be opposite if its direction is applied. Therefore,

made by the second entity. Because of an effort made by the interacting entity, its direction must be opposite if its direction is applied. Therefore, ![]() =

= ![]() holds. In Economics, we can convert an effort made by an entity into a value

holds. In Economics, we can convert an effort made by an entity into a value ![]() . A customer pays a service provider to exchange for an equivalent value of service that the customer asks for. Therefore, we have

. A customer pays a service provider to exchange for an equivalent value of service that the customer asks for. Therefore, we have ![]() =

= ![]() to represent the mutuality law in the sociotechnical service world.

to represent the mutuality law in the sociotechnical service world.

Newton's laws of motion can be verified through experiments and observations. Indeed, scientists have positively verified and demonstrated them for over three centuries. As compared to the physical quantities that are well defined and physically measurable, a service system's systemic mass and effort in the sociotechnical service world are largely subjective. However, we can always find scientific ways to have them to be externally defined quantities when a service setting is given. Consequently, by applying the three fundamental laws of service, scientific findings, and enabling technologies in service businesses, we can make business operations competitive and profitable and enjoy long-term successes in our respective service industries.

4.1.3 A Systemic View of the Fundamental Laws of Service

In the previous section, we proposed three laws of service analogous to Newton's three laws of motion. To make the analogous discussion of the three laws of service easily comprehendible and fully understood, we use Table 4.1 to show the analogous highlights between the laws of motion and service. Indeed, the current socioeconomic service activities largely obey the underlying principles that are implied in the laws of service. In other words, the developed three fundamental laws of service seem to make sense in reality. However, we understand that variables must be truly and externally defined to be quantities in satisfying the canons of scientific rigor. By doing so, the above-mentioned three fundamental laws can be truly applied to describe basic rules about how the experience of a service changes. The three fundamental laws of service can then be the three essential pillars in support of Service Science (Figure 4.2).

Table 4.1 Analogous Highlights Between the Laws of Motion and Service

| Law | Motion | Service Experience |

| The first law | Inertia due to zero net force ( |

Inertia due to no changing effort ( |

| The second law | ||

| The third law |

Figure 4.2 The three fundamental laws of service.

As discussed earlier, we are interested in the rules and guidelines that can be applied to service engineering and management in general. Thus, we must focus on identifying managerial and operational guidance with scientific rigor for service organizations to achieve effective service marketing, management, and operations in practice. In the physical world, by relying on Newton's three laws of motion we can truly describe the motion dynamics of physical objects in a scientific manner with respect to an inertial frame of reference. In the sociotechnical service world, we lack scientific methods of measuring the systemic mass of a first entity and effort made by a second entity or the interacting entity of the first entity. Therefore, the first compiled three laws of service can be hardly applied to guiding service organizations to enable and govern service offerings in a repeatable, competitive, and profitable manner.

The mass of an object in Physics is well defined and can be instrumentally measured. A scientific definition of mass is given as follows: the mass of an object is the quantity of matter in the object body regardless of its volume or of any forces acting on it. However, different from a physical object, the systemic mass of an entity in the sociotechnical service world is totally subjective. For example, the service experience perceived by a customer will surely be enriched if an additional personal touch has been developed in the service provided for the customer.

Let us use a specific study to show the challenges of defining a systemic mass. In addition to a customer's competence and expectation, Johnston (1995) reveals that satisfactory determinants of a banking service can be radically categorized into two types. One is the instrumental determinants that define the performance of technical functions of the service; the other is the expressive determinants that then define the psychological performance of the service. Johnston identifies some determinants of quality predominate over others in the banking industry. The main sources of satisfaction are attentiveness, responsiveness, care, and friendliness, while the main sources of dissatisfaction are integrity, reliability, responsiveness, availability, and functionality.

The inertia of an object is a property of matter in the object by which it remains in its current state unless acted upon by some external force. As soon as there is an external force acted on the object, the rate of change of its current state is directly proportional to the external force but inversely proportional to its mass. On the basis of logical thinking and inductive reasoning, we know that the service experience perceived by a customer has a similar property. We can call it the inertia of service experience. From the earlier discussion, we also understand that the experience of service perceived by a customer remains the same unless acted upon by changed external “force” or effort. The earlier example clearly argues that the attentiveness, responsiveness, care, friendliness, integrity, reliability, responsiveness, availability, and functionality of a banking service are largely measured across the whole banking service system in a subjective manner. The quantity of “matter and mind” in the customer is surely of a systemic nature. We know that the second law of service holds, but we can hardly know how to measure the systemic mass of a customer.

In general, a service satisfies both the utilitarian and sociopsychological needs of a customer; the quantity of “matter” in the customer mind is subjective in nature. It is not difficult to find out that defining a systemic mass for an entity is almost impossible. As an individual entity cannot be precisely measured in a quantitative manner, we should take a different path by looking into its collective nature.

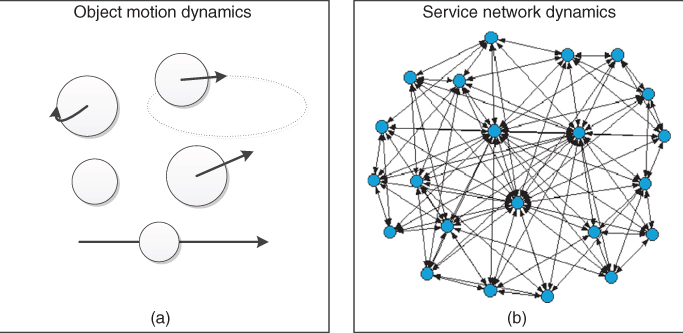

When we look at the services in a collective manner, we find that the approach taken in social sciences could shed us a promising light in finding appropriate methods of studying services in a quantitative manner (Figure 4.3). In many aspects of social sciences, such as psychology, economics, sociology, marketing, drug discovery, and political science, quantitative research as a scientific method has been widely used for many decades. Statistics is the fundamental mathematics that is widely used by social scientists, researchers, and practitioners in conducting quantitative research. For example, based on a big sample of data that are collected over a given study period, we conduct quantitative research using statistical methods to confirm or decipher the causal relationships of certain social phenomena in which we have great interest.

Figure 4.3 The service network dynamics versus the object motion dynamics. (a) Individual object approach and (b) holistic and systemic approach.

“In the social sciences, quantitative research refers to the systematic empirical investigation of social phenomena via statistical, mathematical or computational techniques. The objective of quantitative research is to develop and employ mathematical models, theories and/or hypotheses pertaining to phenomena. The process of measurement is central to quantitative research because it provides the fundamental connection between empirical observation and mathematical expression of quantitative relationships. Quantitative data is any data that is in numerical form such as statistics, percentages, etc.” “The researcher analyzes the data with the help of statistics. The researcher is hoping the numbers will yield an unbiased result that can be generalized to some larger population. Qualitative research, on the other hand, asks broad questions and collects word data from participants. The researcher looks for themes and describes the information in themes and patterns exclusive to that set of participants” (QRWiki, (2012).

Further, Figure 4.3 shows the fundamental difference between the dynamics of service network and object motion. The motion of an object can be well described; the collectives of minds and technical functions that mainly constitute services and considerably drive corresponding sociotechnical phenomena are highly interactive and subjective. Obviously, the approach to studying individual physical objects cannot be directly applied to studying service experiences.

We know that service is considered as a transformation process in which both provider-side and customer-side people participate in an interactive manner, applying relevant knowledge, skills, and experiences in order to cocreate mutual benefits for the service providers and their customers. Thus, the interactions between service providers and customers are the key to the services performed by the service providers and their customers. Because it is the collection of minds and technical functions in services that mainly constitutes the services, the corresponding sociotechnical services are highly social and interactive. The measured behavior and outcomes are largely subjective in nature.

Therefore, in an effort to further develop the laws of service that are practically applicable for the service industry to meet the needs of today's service-led economy, we must take all the service characteristics we discussed in the previous chapters into full consideration. In other words, we must rethink the laws of service using a systemic or holistic approach, aimed at overcoming the challenges of finding the scientific method to define the systemic mass of a service system or an alternative rule in a similar nature of the second law of service in Service Science. In summary, the following considerations become necessary:

- Services are cocreated by the service providers and customers; the service providers and customers as a whole constitutes a sociotechnical service system. Scientifically assessing services should be done in a collective manner across the service system. In other words, we might evaluate a service when needed; however, only the collection of services provides scientific insights into the service system under study. As a result, instead of studying the service experience perceived by an individual entity using the systemic mass of the studied entity, we should focus on the behaviors of the group of entities under study or the total service experiences perceived by the group using statistic methods that are well adopted in quantitative research.

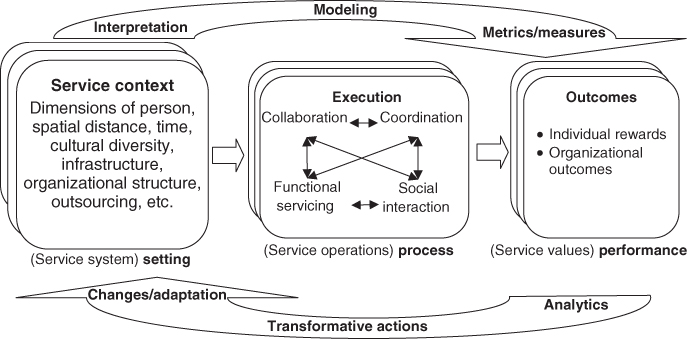

- Because services are people-centric, truly cultural and bilateral, holistic or systemic viewpoints are essential. The holistic or systemic viewpoint focuses on the “big picture,” interacting relationships, and long-range view of systems dynamics. By paying attention to the whole, a holistic perspective helps us understand and orchestrate service interactions across business domains and throughout the service lifecycle. Figure 4.4 shows our envisioned qualitative and quantitative approach, which must be people-centric, systemic, evolutionary, and iterative (Andriessen and Verburg, (2004); Qiu, (2009). More detailed discussions of this proposed approach will be provided in Chapters 5 and 6.

Figure 4.4 A qualitative and quantitative approach to interpret a service system throughout its lifecycle.

Adapted and revised from Andriessen and Verburg (2004).

By relying on quantitative approaches, we can then recompile the laws of service from the earlier discussion:

- Service's First Law. If there is no changing effort on a collection of services, then the value

of the collection of services perceived by customers remains the same.

of the collection of services perceived by customers remains the same.  is proportional to or a function of

is proportional to or a function of  , that is,

, that is,  .

. - Service's Second Law. The service efficacy

of a service system is directly proportional to the changing effort

of a service system is directly proportional to the changing effort  that is applied to the service system, is in the direction of the changing effort, but is inversely proportional to the systemic resistance

that is applied to the service system, is in the direction of the changing effort, but is inversely proportional to the systemic resistance  of the entity, that is,

of the entity, that is,  . The systemic resistance essentially is the inertia of a service system that can be approximately measured by its relative systemic complexity and/or inefficiency due to the bureaucracy embedded in the service system. Therefore,

. The systemic resistance essentially is the inertia of a service system that can be approximately measured by its relative systemic complexity and/or inefficiency due to the bureaucracy embedded in the service system. Therefore,  .

. - Service's Third Law. When customers apply an effort

on providers in a service system, the providers simultaneously apply an effort

on providers in a service system, the providers simultaneously apply an effort  on the customers. This means that

on the customers. This means that  and

and  are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. When the values of both service providers and customers are used, we have

are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. When the values of both service providers and customers are used, we have  =

=  ,

,  ,

,  .

.

Table 4.2 highlights the newly compiled laws of service. When we look into the difference we have made in Table 4.2, we know that we are surely heading into the right direction. The defined new relationships that describe how service values change with the changing efforts can be realistically and viably interpreted, defined, and managed in service organizations.

Table 4.2 The Laws of and Service

| Law | Service Experience Collectives that are Realistically Gauged by Value | Service Experience |

| The first law | Inertia due to no changing effort |

Inertia due to no changing effort ( |

| The second law | ||

| The third law |

4.2 The Service Encounter Sociophysics

As discussed earlier, a service is people-centric, truly cultural, and bilateral. From the observations of service rendering in practice and research outcomes from the service community, we know that the type and nature of a service dictates how the service is performed. The service system that offers the service accordingly defines how a series of service encounters could and should occur throughout its service lifecycle. The type, order, frequency, timing, time, efficiency, and effectiveness of the series of service encounters throughout the service lifecycles determine the quality of services perceived by customers who purchase and consume the services (Bitner, (1992); Chase and Dasu, (2008). To a given service system, it is well recognized that the perceived service value and quality by its customers substantially impact the satisfaction and loyalty of the customers in the long run.

The above-mentioned social and transactional interactions in service encounters can be direct or indirect in today's digital and global economy. Face-to-face interactions are direct; virtual interactions, which are mediated through technical applications (i.e., phone, online social media, or self-served device), are indirect (Bitner et al., (1990); Bitner et al., (2000); Svensson, (2004); Svensson, (2006); Meyer and Schwager, (2007); Schneider and Bowen, (2010). Hence, depending on the complexity and nature of an executed service, the social and psychological expectations and needs of a customer at the time that a service encounter occurs can be directly and/or indirectly, slightly or significantly influenced by the experiences of preceding service encounters perceived by the customer or other customers.

For instance, in a service encounter chain, a later encounter is inevitably influenced by the immediately preceding one; employees or customers could also be influenced by other previous encounters that they may have had before if those are somewhat functionally or sociopsychologically related. By relying on conventional wisdom, Ramdas et al. (2012) study four different dimensions in service encounters, including the structure of the interactions, the service boundary, the allocation of service tasks, and the delivery location. They suggest that service providers should define and deliver services by examining interactions among the four dimensions, aimed at creating more mutual values for both customers and providers. However, conventional wisdom is not necessarily true in today's digital and global economy, in which change is the only constant. In order to have a body of knowledge that can be scientifically applied in such a dynamic environment, we need Service Science that can help us foster the planning, design, engineering, delivery and operations of service encounters in a comprehensive and holistic manner.

More broadly, as the velocity of globalization accelerates, the changes and influences are more ambient, quick, and substantial, impacting us as providers or customers in dynamic and complex ways that have not seen before. Service encounters, as a matter of fact, form a time series network in service provision. The understanding of service encounter networks is essential for service providers to be able to design, offer, and manage services for competitive advantage.

The prior lack of means to monitor and capture people's dynamics throughout the service lifecycle has prohibited us from gaining insights into the service encounter chains or networks. Promisingly, the rapid development of digitization and networking technologies has made possible the needed means and methods to change this. Therefore, now is the time for us to rethink service encounters and explore those social and transactional interactions in a deeper and more sophisticated manner than ever before.

4.2.1 The Service Encounter Dynamics of a Service System

Once again, service is an application of relevant knowledge, skills, and experiences to benefit both service providers and customers. To a customer, the encounter of a service or “moment of truth” frequently is the service from the customer's perspective (Bitner et al., (1990). However, from the perspective of a system, service is a process of transformation of the customer's needs utilizing the operations' resources, in which dimensions of customer experience manifest themselves in the themes of a service encounter or service encounter chain. The dynamics of service encounter networks of a service system essentially describes the systemic behavior of the service system in the service engineering and management perspective.

As discussed earlier service encounters derived from human interactions in services are inherently dyadic and collaborative both socially and psychologically (Shostack, (1985); Solomon et al., (1985); Schneider and Bowen, (2010). Service encounters involve all interacting activities in the service delivery process, resulting in reciprocal influence between service providers and customers. For example, consumers are the customers in the retailing service sector; students are the customers in educational service systems; patients then are the customers in health care delivery systems. By simply observing the service cocreation processes in our daily life, we are sure that it is the service encounter that enables the necessary manifest function that engages the providers and the customers in order to show the “truth” of service.

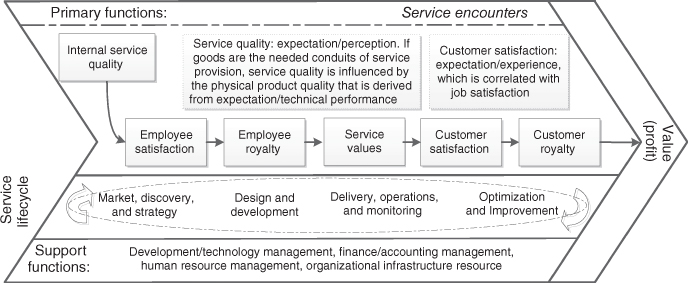

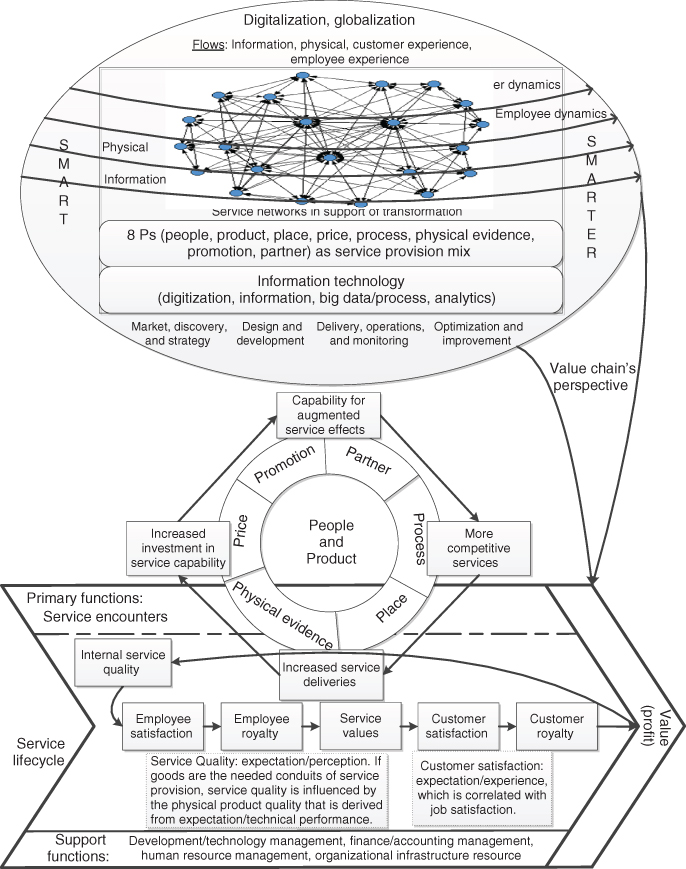

Most service businesses understand that the service profit (or value) chain relies on the creation of loyal customers through their experience with excellent service encounters (Figure 4.5) (Qiu, (2013b). Significant research on the service profit chain has revealed the changing, complex, cascading, and highly correlated relationships among job satisfaction, customer satisfaction and loyalty, and business profitability in service firms (Taylor, (1977); Bolton and Drew, (1991); Heskett et al., (1994); Zeithaml, (2000); Lovelock and Wirtz, (2007); Gracia et al., (2010).

Figure 4.5 The service organizational profit chain.

The majority of academics and practitioners in the service community uniformly agree that the service encounters between employees and customers are central to the delivery of services (Czepiel et al., (1985); Bitner, (1992); Heskett et al., (1994). Scholars in the service marketing field, in particular, have been interested in the dynamics of service encounters for decades (Solomon et al., (1985); Meyer and Schwager, (2007). At each point of customer interaction, the customer gains experience that essentially is the perceived effect of the fulfillments in both the utilitarian and sociopsychological dimensions (Larson, (1987); Chase and Dasu, (2008); Bradley et al., (2010). Utilitarian needs are met through the performance of the desired service utility functions that are typically defined in specifications (e.g., default general references, signed service agreements), frequently including both technical and functional units. However, meeting the social and psychological needs of customers and employees presents more challenges as the vast array of sociopsychological needs vary with time, duration, servicescape, and an individual's expectation and competency (Bitner, (1990); Bitner, (1992); Bitner et al., (1994); Keillor et al., (2004); Svensson, (2004); Bradley et al., (2010); Qiu, (2013b).

The quality of a firm's services is the overall perception that results from comparing the firm's actual performance with the customers' general expectations of how firms in that industry should perform. Empirical studies affirm the importance of the service encounters in evaluating the overall quality and satisfaction with a firm's service (Parasuraman et al., (1985) (1988); Bitner et al., (1990). The customers' satisfaction is mainly determined by their experience with the service provider; the users' experience, in turn, is their perception based on their experienced service encounters. Because customers are increasingly susceptible to the market changes, competitive service firms must engineer and execute service encounters that consistently yield superior user experience in order to win the allegiance of the time-pressed customers.

Service quality, customer experience, and job and customer satisfaction all are quite subjective. Recent studies have revealed that job satisfaction and customer experience are highly correlated; indeed, in many aspects, they mutually influence each other (Svensson, (2006); Bradley et al., (2010). However, in service encounters, many academics and practitioners over the years have recognized the interactions but have separated the customer and provider perspectives:

- From the customers' perceptive, scholars have developed a body of knowledge primarily in the service marketing arena. These contributions were mainly derived from empirical studies and are related to service quality, service encounters, service failure and recovery, and customer satisfaction and loyalty (Parasuraman et al., (1985); Surprenant and Solomon, (1987); Smith et al., (1999); Meyer and Schwager, (2007). The determinants of service quality surely vary with services (Bitner et al., (1990); Johnston, (1995).

- From the providers' perspective, scholars have also mainly relied on empirical research with a focus on the dynamics of the providers' service delivery systems. A body of knowledge relating to job satisfaction, provider performance, employee job stress, morale and commitment, and their wellbeing has been developed (Taylor, (1977); Bitner, (1990); Bitner, (1992); Bitner et al., (1994); Lloyd and Luk, (2009).

Czepiel (1990) advocates that both customer and provider perceptions should be the focus of any study in service encounters. Svensson (2006) also articulates that service encounters should be explored in a deeper and more sophisticated manner. By considering service encounter successes from both the employee and customer perspectives, Bradley et al. (2010) propose a dyadic psychosocial needs approach to exploring the practical insights into the effective resolution of common service delivery problems. They conclude that there are eight psychological needs in service encounters that require attention: cognition, competence, control, power, justice, trust, respect, and pleasing relations.

Indeed, most of the literature has looked upon service encounters mainly in the service delivery processes. In pursuit of further development of Service Science in this book, we study service encounters more broadly by exploring all stages of the service lifecycle, as service providers now demand the comprehensive understandings of social and transactional interactions between customers and employees in the areas of service market, design and development, delivery, and operations and management.

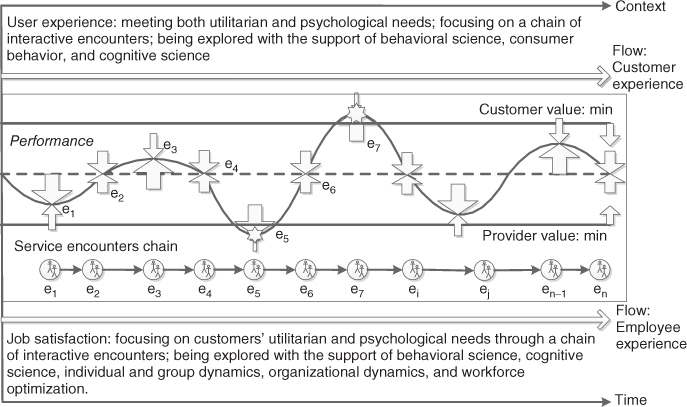

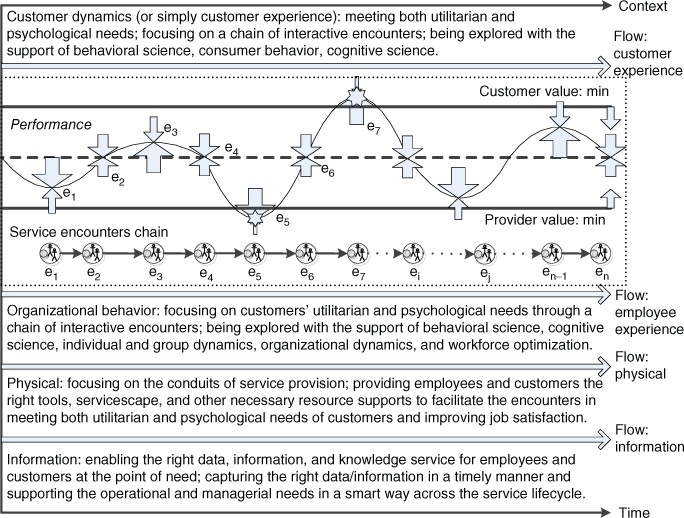

In summary, service interactions not only fulfill the manifest function of socioeconomic transactions in general, namely, satisfying the involved entities' material/utilitarian needs, but also their corresponding latent functions, namely, meeting the social and psychosocial needs of employees and customers (Bradley et al., (2010). Figure 4.6 illustrates the dynamics of service encounters in the dimensions of performance, time, and service context or servicescape (Qiu, (2013b). This book looks into the science of service by taking the lifecycle and systemic perspectives. It will be essential and promising for the compiled laws of service to be viably applicable for the governance and guidance of service encounters engineering and management throughout the service lifecycle.

Figure 4.6 The dynamics of service encounters with performance/time/context.

4.2.2 The Laws of Service for Service Encounters

As mentioned earlier, Newton's three laws are useful approximations at the scales and speeds of daily life, in which physical objects move at the much slower speed than light. It is well understood that the first law of motion was used to establish a frame of reference for which the other laws are applicable. In other words, the other two laws of motion are not applicable for use in certain circumstances, such as one when objects travel at the speed of light or higher.

As indicated in Chapter 3, the worldwide service research community has conducted a variety of service studies in many focused areas for several decades, including service operations, marketing, and organizational structure and behavior, and economic transformation. Indeed, a lot of pioneer studies and fruitful research findings have helped the service industry tackle a variety of problems in practice over the years. However, as the service industries continue to evolve fast, service organizations are confronting more and more challenging and new issues in meeting the dynamic changes of services around the world. Emerging and under-researched areas in service have been explored and identified by Ostrom et al. (2010) through collecting viewpoints from over 200 academics across 15 relevant disciplines and from organizations in 32 countries.

More specifically, to spotlight service research priorities by capturing the state of the art and more importantly looking forward to understand and reflect the emerging future needs in academia and practice, Ostrom et al. (2010) spent 18 months collecting and interpreting the viewpoints of academic scholars and leading practitioners around the world. Their great efforts lead to identifying a set of global, interdisciplinary research priorities in the science of service. As the excellent result of their hard work, the following 10 overarching research priorities have been identified:

- Fostering service infusion and growth

- Improving wellbeing through transformative service

- Creating and maintaining a service culture

- Stimulating service innovation

- Enhancing service design

- Optimizing service networks and value chains

- Effectively branding and selling services

- Enhancing the service experience through cocreation

- Measuring and optimizing the value of service

- Leveraging technology to advance service

Note that their hard work confirms that the science of service has become exceedingly broad, interdisciplinary, and cross-functional. We understand that their intention was to call for swift action to study the emerging service research topics from academics and practitioners in the service community. Their findings are definitely subjective because a qualitative research rather than quantitative study method was radically applied during the compilation process. However, their interesting results are of great value, undoubtedly sparking discussion and spurring thinking about service research areas worldwide.

This book mainly takes quantitative approaches to address service issues in a quite unique way. Although it seems that this book covers several priorities in the above-mentioned list, we do understand that it is impossible that the above-compiled laws of service are universally applicable. Therefore, like Newton's laws of motion, we should establish a frame of reference in a similar way to make sure that the laws of service are applicable for the established reference frame. As this book mainly explore service encounters, we should further develop the laws of service and make sure they are truly applicable for the investigations that we will continue to explore and present in the following chapters.

We as the service provider know that customer interactions go beyond the service delivery processes and must include all influential in-person or virtual contacts during the design, development, and preparation of service encounters. In other words, we now fully understand that customers consume and perceive services through a list of service encounters that truly occur throughout the service lifecycle. Therefore, service research to gain a perspective of collective service and systemic behavior must focus on the dynamics of service systems across the service lifecycle. Although qualitative research certainly helps to identify certain managerial guidance in service engineering, operations, and management, quantitative research is certainly the best option in providing the insights into the dynamics of service with scientific rigor when service explorations must be carried out by taking the lifecycle and systemic perspective of service.

Please keep in mind, interactions between customers and providers can occur in different ways, face-to-face or virtually, directly or indirectly. As discussed earlier, personifying self-serving units thus becomes essential for a service provider to provide empathic and pleasing supports in service provision. As a result, the service provider can avoid creating apathy and negativity that people might feel when self-services are radically supplementary under some circumstances.

Furthermore, the value and service experience must be calculated in a collective, personifying, and systems manner. Theoretically and practically, the laws of service that are finally presented in this book should be applicable for describing the rules and guidelines for service interaction-oriented service networks (Figure 4.3b). Similar to econophysics with a root in statistical physics using probabilistic and statistical methods, sociophysics (Galam et al., (1982); Galam, (2008) deals with five main subjects of modeling, including democratic voting in bottom up hierarchical systems, decision making, fragmentation versus coalitions, and terrorism and opinion dynamics. In Service Science, we believe that the study of the dynamics of service systems shall develop service-focused sociophysics further, in which core variables must be definable and measurable quantities, directly or indirectly.

As we focus on the fundamental laws of sociophysics in service, we compile the laws of service for service interaction-oriented service networks as follows:

- Service Encounter's First Law (A Frame of Reference—Systemic Inertia). The human interactions that essentially create and drive the process of value cocreation in service characterize a service system. If there is no changing effort

(i.e., a systemic disruption force) on the collective service and systemic behavior of the service system, then the value

(i.e., a systemic disruption force) on the collective service and systemic behavior of the service system, then the value  converted from the collective service experience perceived by customers and providers remains the same.

converted from the collective service experience perceived by customers and providers remains the same.  is proportional to or a function of

is proportional to or a function of  , that is,

, that is,  . If respective values from customers and providers are measured, we have

. If respective values from customers and providers are measured, we have  and

and  , where

, where  and

and  . Therefore, we have

. Therefore, we have  .

. - Service Encounter's Second Law (Systemic Disruption). The service efficacy

of a service system is directly proportional to a systemic disruption force

of a service system is directly proportional to a systemic disruption force  , which is applied to the service system, is in the direction of the systemic disruption force, but is inversely proportional to the systemic resistance

, which is applied to the service system, is in the direction of the systemic disruption force, but is inversely proportional to the systemic resistance  of the service system, that is,

of the service system, that is,  . The systemic resistance essentially is the systemic inertia of a service system that can be approximately measured by its relative systemic complexity and/or inefficiency due to the bureaucracy embedded in the service system. In theory, the second law holds regardless of the constituent units. However, the quantity value of the systemic resistance of a service system is always measured collectively by including both customers and providers involved in the service system. In other words, as the dynamics of service networks must be described by the collective service and systemic behavior of the interactions between customers and providers, the variables in the second law of service for service encounters are always measured in a collective manner. Therefore, we have

. The systemic resistance essentially is the systemic inertia of a service system that can be approximately measured by its relative systemic complexity and/or inefficiency due to the bureaucracy embedded in the service system. In theory, the second law holds regardless of the constituent units. However, the quantity value of the systemic resistance of a service system is always measured collectively by including both customers and providers involved in the service system. In other words, as the dynamics of service networks must be described by the collective service and systemic behavior of the interactions between customers and providers, the variables in the second law of service for service encounters are always measured in a collective manner. Therefore, we have  for the service system as a whole.

for the service system as a whole. - Service Encounter's Third Law (Value Cocreation or Mutuality). When the customers apply an effort

on the providers in a service system, the providers simultaneously apply an effort

on the providers in a service system, the providers simultaneously apply an effort  =

=  on the customers. This means that

on the customers. This means that  and

and  are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. When the values of both service providers and customers are used, we have

are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. When the values of both service providers and customers are used, we have  =

=  ,

,  ,

,  . Although the meanings and numbers in the measured values are surely different between the customers and providers, their socioeconomic values when converted must be comparatively equivalent.

. Although the meanings and numbers in the measured values are surely different between the customers and providers, their socioeconomic values when converted must be comparatively equivalent.

Once again, we understand that the science of service relies on both quantitative and qualitative approaches. Many academics and practitioners have pioneered many managerial guidelines and methodologies to help the service industry to compete. However, the above-presented fundamental laws of service help us frame and investigate service issues in a unique way. As readers continue to read the remaining chapters, readers will find that the above-compiled laws of service for service interaction-oriented service networks lay a sound and solid foundation for this book in support of the further study of the needed quantitative and qualitative approaches to address the emerging and challenging service issues.

4.2.3 Service as a Value Cocreation Process: From SMART to SMARTER

In reality, the value of a service is the summation of socioeconomic benefits that providers and customers have accumulated along with the service process trajectory throughout the service lifecycle. Thus, it largely depends on the systemic behavior of the sociotechnical system that offers the service. The service-led economy is now facing the grand challenges of addressing green consumerism, pervasive and ubiquitous digitalization, and accelerated globalization. Note that the service-led economy surely conceptualizes a quantitative service value increase in the percentage of gross domestic product (GDP). Moreover, it indicates a substantive shift in which the services sector must become a main driving engine for future growth and innovation.

To stay competitive in the twenty-first century, service organizations have to rethink their business operations and organizational structures by focusing on people while leveraging the technology (e.g., implementing a novel approach to overcome geographic, social, and cultural barriers to cultivate and enhance the cultures and mechanisms of cocreation, collaboration, and innovations). This will ensure the prompt and cost-effective production and delivery of quality products and competitive and satisfactory services to customers (Qiu, (2012).

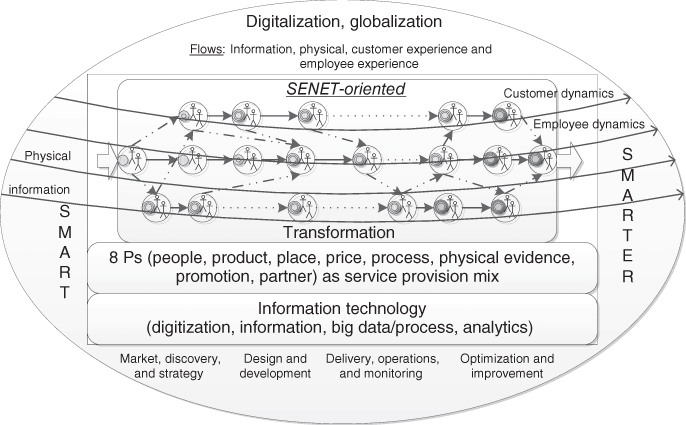

To stay competitive, service organizations understand that they must make their serving processes efficient and cost-effective. To improve their business competitiveness, they should explore a variety of flows that can highly reflect their service status quo in operations (Figure 4.7). These flows include customer experience, organizational behavior, physical support, and information assistance. A customer experience flow focuses on meeting both the utilitarian and psychological needs. An organizational behavior flow focuses on employees' job satisfaction by meeting the customers' utilitarian and psychological needs through enabling a chain of interactive and positive encounters. A physical flow deals with the conduits of service provision. An efficient and effective physical flow should provide employees and customers with the right tools, servicescape, and other necessary resource supports to facilitate the service encounters in meeting both utilitarian and psychological needs of customers while improving job satisfaction. The information assistance flow then aims to capture the right data/information in a timely manner and support the operational and managerial needs in a more intelligent way across the service lifecycle.

Figure 4.7 SENET-oriented sociotechnical process-driven system.

Lacking appropriate tools and methodologies, these highly correlated flows have been separately studied over the years. As discussed earlier, the fast development of digitization, computing, and networking technologies has made possible the needed means and methods to change this. It is surely the time for us to rethink service encounters and explore those social and transactional interactions in a deeper and more sophisticated manner than ever before. As illustrated in Figure 4.7, only when these flows are fully explored in an integrated and collaborative manner, we can operate service systems in a competitive way, making service networks “SMART” and even “SMARTER” over time.

The mnemonic “SMART” is popularly used to guide people to set goals and objectives in practice (Doran, (1981). The common terms behind the letters of “SMARTERS” change from one user, either academic scholar or practitioner, to another, depending on the situation in which the mnemonic is actually applied. However, academics and practitioners have quite often focused on the common characteristics of “SMARTERS,” referring to “specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, timely, evaluative, rewarding, and satisfactory.” As compared to the mnemonic “SMART” that are popularly used to guide people to set goals and objectives in practice, we focus on investigating quantitative approaches by applying these identified characteristics in the models discussed in the remaining chapters of this book.

As indicated in Figure 4.7, virtual, indirect, and other kinds of service encounters should be fully explored and included in the service encounter research. Not just physical and information flows, customer experience and job satisfaction must also be included at the same time when service profit chains are analyzed, planned, and managed. Ultimately, we can efficiently and effectively monitor, capture, and analyze service encounter networks. Therefore, “SMART,” “SMARTER,” and “SMARTERS” are equivoques, which are truly expressions with two meanings. When we explore service systems by well adopting “specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, timely, evaluative, rewarding, and satisfactory” rules, real smart service operations can be fully engineered and delivered over time.

To have smart service operations, we have to make sure that each service encounter in service encounter networks is specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and timely to both service providers and customers. Aligning service activities with corresponding service capability, competence, and necessary physical and information supports from both service providers and customers are thus essential for executing smart service operations. For example, Bradley et al. (2010) confirm that actions in a series of service encounters should be specifically planned, designed, and operated. In case that some of planned actions or events are not well performed, relevant remedy actions or changes should be pinpointed in real time to recover the unsatisfactory service to some extent or for the purpose of further improvement (Tax and Brown, (1998).

Indeed, service interactions must meet respective expectations from both service providers and customers although the expectations and then perceptions are truly different. Because of the existence of differences, the effectiveness of service encounters must be evaluated using a range of different metrics. For instance, we might use the following different metrics to understand their respective effectiveness of service encounters:

- To the Customers. Service time is the time that should be taken to complete a certain function or task. We could use the following measures to evaluate service time: mean service time, mean waiting time, etc.

- To the Provider. Mean waiting time, server utilization, throughput, and average number of customers waiting are frequently used to evaluate the efficiency of services. In addition, we might use mean time between failures (MTBFs) and mean time to recover (MTTR) to determine the reliability of services. MTBF is the mean time that a service might fail; MTTR is the mean time that should be taken to recover after a service failure.

To understand if service encounters meet the needs of both providers and customers, we have to evaluate their respective outcomes perceived from service encounters in service. Similarly, the satisfaction of service encounters must be evaluated using a range of different measures and metrics. For instance, we might use the following metrics to understand the satisfaction of service encounters in a customer perspective.

- Utilitarian or Functional Requirements. Functions or tasks should be performed based on signed contracts or default agreements and references. The contracts can be in the form of certain service-level agreements. To individual customers, default or implied service tasks might be performed, and general service references could be applied to manage the process of transformation and accordingly measure the service utilitarian outcomes.

- Sociopsychological Needs. The feelings that the customer has had during these service encounters. Pleasing and positive feeling perceived in service encounters frequently result in that the provided services excel in values that are simply evaluated based on utilitarian requirements.

Then, we could use the following metrics to understand the satisfaction of service encounters in a provider perspective.

- Utilitarian or Functional Requirements. This should be the same as one that is evaluated by the customers although the values generated from meeting these requirements are surely different.

- Socioemotional Needs. The feelings that the employee have had during these service encounters. As job satisfaction is highly correlated to customer satisfaction, we must ensure that the right tools, setting, and supports are in place to make employees appropriately empowered, capable, and cozy to serve the customers at point of service.

Surely a SENET-oriented sociotechnical process-driven system is effective and competitive only if all the necessary needs of customers can be fully met throughout the service lifecycle.

4.3 Service Science: A Promising Interdisciplinary Field

In the service sector, what really matters in service offering comes to the happiness and satisfaction in service perceived by customers and providers throughout the service lifecycle. Surely, the determinants of service quality vary with services. For instance, the determinants in the banking industry, both satisfying and dissatisfying, primarily include attentiveness/helpfulness, responsiveness, care, availability, reliability, integrity, friendliness, courtesy, communication, competence, functionality, commitment, access, flexibility, aesthetics, cleanliness/tidiness, comfort, and security (Johnston, (1995). Those determinants can be radically categorized into two types. One is the instrumental determinants that define the performance of utilitarian or technical functions of the service; the other is the expressive determinants that then define the psychological performance of the service. Using an empirical study, Johnston identifies some determinants of quality predominate over others in the banking industry. The main sources of satisfaction are attentiveness, responsiveness, care, and friendliness, while the main sources of dissatisfaction are integrity, reliability, responsiveness, availability, and functionality.

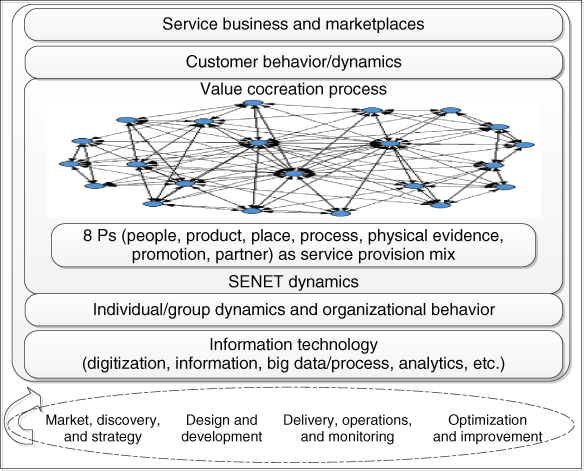

We have discussed earlier that empirical examinations of service value drivers include a variety of factors throughout the service profit (or value) chain (Figure 4.5). We know that internal service quality, job satisfaction, customer perceived service quality, customer satisfaction and loyalty, and profitability in a service organization are highly correlated. In particular, employees' competence and their feeling of empowerment substantially influence the outcomes of service quality, accordingly impacting on customer satisfaction and loyalty (Heskett et al., (1994); Loveman, (1998); Durvasula et al., (2005). To a service organization, a virtuous circle is essentially what makes it competitive in the long run (Figure 4.8) (Heskett et al., (1990); Chesbrough, (2011b). As the primary function of service is to engineer, execute, and support service encounters, we must rethink service encounters and find the scientific ways to build and manage people-centric, information-enabled, cocreation-oriented, and innovative service organizations with a focus on the dynamics of service encounters throughout the lifecycle of service.

Figure 4.8 SENET-oriented service profit chain with a virtuous cocreation and innovation circle.

It becomes clear that both service providers and customers are interweaved in the process of service transformation, in which dimensions of customer experience manifest themselves in the themes of service encounters. Service encounters or service networks are thus dynamic, collective, and evolutionary in nature. Because their cocreation relationships become the general characteristics of the modern services, the consistent sensing, interaction, and creativity from customers' feedbacks, participations, or consumptions throughout the lifecycle of service play a pivotal role in service provision (Drogseth, (2012). The complexity in light of dynamics of systemic behavior in a service organization throughout the service profit chain (Figure 4.8) clearly shows that service encounter networks must be explored in an integrated manner with scientific rigor. It is the virtuous cocreation-oriented innovation circle that makes a service value chain competitive and profitable (Chesbrough, (2011a).

Quantitative research of service relies on methods and tools to capture and understand the dynamics of service networks in the setting described in Figure 4.8. Chase and Dasu (2008) argue that behavioral science offers new insights into better service management. For instance, we should design and manage service encounters with a help of the understandings of how people experience social interactions, what biases they bring to affect their feelings, and how cognitive competency and experiences impact their storing memories. According to Chase and Dasu (2001) (2008), we have to consider the key points in both utilitarian and sociopsychological dimensions when service encounter networks are analyzed, so those exceedingly critical moments of truth can be well planned, designed, and managed.

We must make customer experience enjoyable and memorable. The reality is that perception is what really matters in customer experience. However, service quality, customer experience, and job and customer satisfaction all are quite subjective (Chase, 1978). Fortunately, over the years psychologists and cognitive scientists have poured tremendous efforts in interpreting human behaviors with fascinating outcomes that help us to understand the complex process of the formation of human's perceptions. For instance, we are surely concerned with the following perception perspectives in service (Chase and Dasu, (2001); Chase and Dasu, (2008)

- Sequence Effects. People typically conclude their assessments of feelings after a series of encounters based on the trend in the sequence of pleasure, a few significant moments, and the ending. People usually prefer to enjoy the steady and sequential improvement, fast response, and quick recovery to an unsatisfied event. The uptick and happy ending has been always the most intriguing experience in all encounters in service.

- Duration Effects. The perceptions of time's passage are surely subjective. For a service encounter, people largely appreciate the experienced pleasurable content and how the service encounter is arranged rather than how long it takes. It is typical that people will not notice how long it takes when they are pleasurably and mentally engaged in the service encounter. Of course, people's expectation of the length of processing time will impact their evaluation of the duration.

- Rationalization Effects. “The more empowered and engaged they feel, the less angry they are when something goes wrong.” “[P]eople want explanations, and they'll make them up if they have to. The explanation will nearly always focus on something they can observe—soothing that is discrete and concrete enough to be changed in their if-only fantasies” (Chase and Dasu, (2001), p. 81).

- Perceived Control. The customer's comfort and pleasure in a service encounter are positively influenced by the responsibility the customer has during the service encounter.

We should optimally design and influence customers' reactions to the sequence of service encounters, properly arrange and control the segments of each service encounter, appropriately adopt the mechanisms to help educate, empower, comfort, and engage the customers, and turn over certain control to the customers to improve their engagements in a positive way whenever possible (Qiu, 2013b).

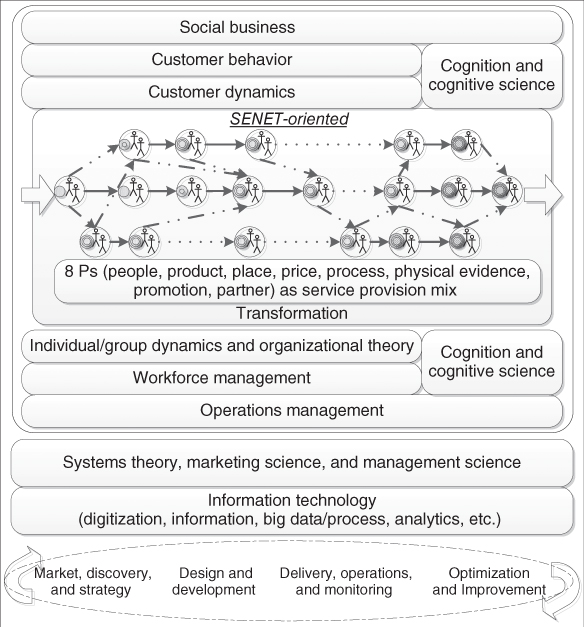

As discussed earlier, in order to help service organizations offer competitive services to customers, academics and practitioners worldwide have conducted service research in focused areas for many decades. Endeavors in certain focused fields have a long history, resulting in a lot of excellent work from many constituent parts of the study of services (Larson, (2011). Rigorous methodologies and frameworks allow us to conduct advanced descriptive and prescriptive research of a service spanning its lifecycle in an integral and quantitative manner. With the support of systems theory, marketing science, operations research, management science, advanced computing, and communication technology, recent advancements in (online) social networks, informatics, and analytics, and others, the means do exist (Figure 4.9).

Figure 4.9 Service Science as a promising interdisciplinary field.

As discussed earlier, for any given phase in the service lifecycle, the literature has shown many outstanding works. For a given service, its technical requirements are most likely materialized in its service-bundled products with the support of the needed operational resources. Indeed, how service encounters substantially impact perceived service quality in a variety of dimensions in perspectives of the service providers, customers, or both has been well studied (Parasuraman et al., (1988); Bitner, (1990); Bitner, (1992); Bradley et al., (2010). However, these human interactions, in general, have not well explored by considering them throughout the service lifecycle in an integrative and collaborative manner. In other words, how these intensive and broad interactions at one phase impact the other phases of service provision have been largely ignored so far in service research. We must rethink service encounters by integrating these human interactions into a service encounter chain, from beginning to end across the service lifecycle, so that we can look into services defined in this book using a holistic, systems, and integrative approach (Qiu, (2013b).

Figure 4.10 Systemic view of the dynamics of a service system based on the laws of service.

Service Science is a promising interdisciplinary field. On the basis of the laws of service for service encounters, we can view the systems behavior of a service organization as the dynamics of cocreation-oriented service networks (Figure 4.10). The service encounter networks evolve over time, which must be evaluated, managed,

and controlled in a real-time and quantitative manner in order to stay competitive. To avoid platitudinous ponderosity, this book takes the following “SMART” points into consideration to develop the science of service.