CHAPTER 2

Microfinance – the Concept

I believe in microfinance because it isn't just a path out of poverty. It's the road to self‐reliance. By allowing people to team up and literally become their own bank, you can mobilize people and resources and alleviate poverty on the global scale.

Her Majesty Queen Rania al‐Abdullah of Jordan1

The financial markets in many industrialized countries are a result of capital structures similar to those of microfinance.

Microfinance is a form of impact investing yielding not only financial but also social returns; a sustainable combination of economic performance and social impact.

Financial inclusion by means of facilitated access to financial products promotes higher income, leads to better health and education and reduces economic inequality.

2.1 HISTORY

Microfinance has become a household name and a story of success over the last few decades. However, its origins date back much further. Today's modern financial markets in many industrialized countries are a result of capital structures similar to those of microfinance. Deeming the concept of microfinance to be a relatively new one, and thereby confining its roots to the recent past, would not only mar its historical importance and overall impact but also neglect the consolidated findings of the past centuries. These invaluable experiences are the basis for any future development.

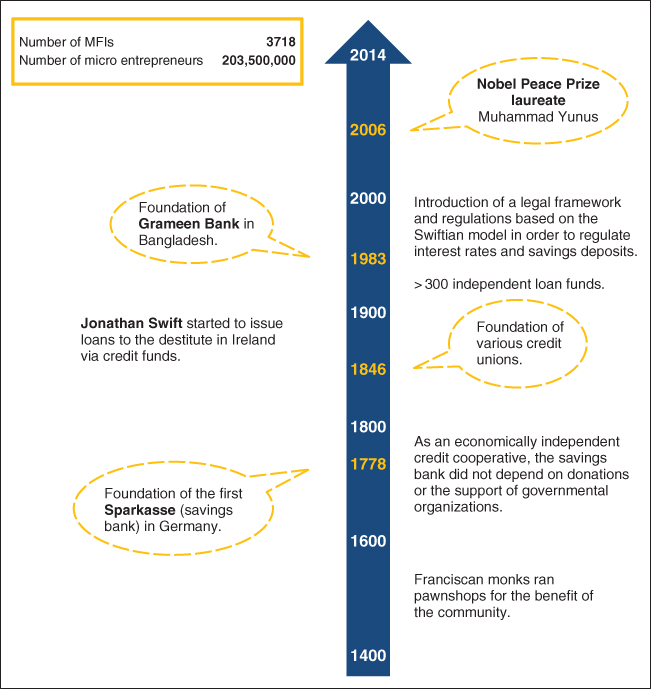

As early as back in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, Franciscan monks founded collective pawnshops (see Figure 2.1). Their aim was to assist poverty‐stricken segments of the population to secure their economic existence at times of crisis. Typically, the pawnbroker would hold items of value for which a small fee was charged in return for safe custody. The resulting revenues would allow the monks to cover their operative costs. In Italy alone, the concept spread to 214 social institutions that were based on so‐called monti di pietà (mounts of piety) as their capital base. Alongside the borrowers, there were sponsors who financially boosted the capital stock.2

FIGURE 2.1 The History of Microfinance

Data Source: Becker (2010); Hollis and Sweetman (2004); Menning (1992); Reed, Marsden, Ortega, Rivera and Rogers (2015); Seibel (2003); savings banks, the Raiffeisen Group and cooperative banks

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, the prolific Irish writer Jonathan Swift instigated credit funds that would issue smaller amounts of cash to people in need in Dublin. Initially, interest‐free collective loans from donations were granted, and their weekly repayments were safeguarded by means of mutual monitoring. The introduction of a legal framework and regulations authorized for the calculation of interest and savings collection. As a result, and based on the Swiftian model, more than 300 economically independent credit funds were introduced by the mid‐nineteenth century. They differed in size and client structure as well as in geographical focus, and covered a wide range of microcredits.3 Returns and savings deposits led to tremendous growth in the various credit institutions, allowing more than 20 per cent of all Irish households to benefit from them.

At the same time, Germany saw the arrival of the credit cooperative system, with the foundation of the very first savings association in Hamburg in 1778 and the foundation of the first savings bank in 1801. Savings deposits were established and loans were granted to smaller enterprises and farmers. In 1846, Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen and Hermann Schulze‐Delitzsch founded credit cooperatives that would establish savings deposits in both rural and urban areas and issue microloans. Shortly after their foundation, both cooperatives were able to operate economically independently, that is, entirely without the support of donations or governmental organizations.4 To this day, the core of this business and financial model is inherent to the orientation of these organizations, which incidentally have all grown into major commercial banks.5

The beginnings of modern microfinance in developing countries are attributed to Muhammad Yunus and the positioning of his Grameen Bank in the mid‐1980s. Yunus founded Grameen Bank to enable poverty‐stricken members of the population to gain access to capital in the form of microcredits. In 2006, the economist, who had been trained in the USA, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts in the field. As a professor at a university in the south‐east of Bangladesh, Yunus had been jarred by the unspeakable famine raging through his country, leaving tens of thousands dead. In 1976, he began to issue small loans to households in neighboring villages. The privately granted capital was enough to enable the villagers to set up basic business activities that provided a sustainable income.

Despite the fact that no collateral had to be provided, repayments were on time. Yunus expanded the concept in collaboration with the Central Bank of Bangladesh and founded Grameen Bank, which to this day continues to issue loans to low‐income segments of the population nationwide. The bank's winning formula is their system of solidarity lending, where microcredit clients accept joint liability for their loans. By the early 1990s, Grameen already had more than one million clients. Today a multiple thereof, a staggering 8.7 million, profit from the bank's services.6 Simultaneously, other financial markets all over the world started to develop, notably the microfinance service provider ACCION in Brazil and Bank Rakyat in Indonesia. A number of microfinance institutions (MFIs) have stood the test of time and safely established themselves. They are all based on the Grameen Bank business model and are continuously and successfully developing it further.7

Microfinance has grown impressively and rapidly since 1997. According to the Microcredit Summit Campaign Report in 2014, over 4000 microfinance institutions have reached more than 200 million clients with a standing credit (see Figure 2.2). In other words, each MFI on average serves 55,000 clients. More than 115.5 million clients count among the poorest of the poor when they enter a microfinance program.8

FIGURE 2.2 Growth of Clients and Institutions

Data Source: Reed, Marsden, Ortega, Rivera and Rogers (2015)

2.2 DEFINITION AND GOALS

According to estimates, about a quarter of the 500 million poor all over the world engage in micro enterprises and business activities, yet the majority do not have access to adequate and sustainable financial products.9 Microfinance was primarily devised and conceived as a developmental approach that aimed to support those at the bottom of the pyramid. The term “microfinance” sensu stricto refers to the provision of financial services to low‐income clients lacking sufficient funds for entrepreneurial activities.

The financial services mentioned above involve the granting of loans and savings deposits; however, insurance and payment services are increasingly being offered. In the broader sense, the term equally embraces the sundry non‐financial and social services that are being provided by microfinance institutions, such as the imparting of financial knowledge, the development of intergroup leadership competencies, as well as educational and health services.10 The definition of microfinance very often comprises financial as well as social services and is not limited to the realm of classic banking. Impact investing – a form of investment where both financial and social returns are generated – is a hypernym of microfinance and therefore has to be understood as a comprehensive developmental tool.11

From the point of view of MFIs, microfinance activities predominantly consist of the granting of microcredits intended to increase business capital, the assessment of borrowers and their planned investments, and the acceptance of savings deposits and credit control. Despite the fact that many microfinance institutions provide additional non‐financial services, these activities transcend the definition of the traditional concept of microfinance. They may, however, be regarded as a progression that aims to steadily improve its products and broaden its range of services in order to meet client needs.

The exclusion of the poor from most parts of the economic and financial system is largely responsible for their desolate economic and financial situation. The inclusion of low‐income segments of the population into the financial system is therefore a central objective of microfinance. This is all the more obvious as nowadays microfinance products and services have evidently broken the mold of what is known as the classic microcredit. The poor no longer only make use of financial services for business purposes, but increasingly invest in their health and education, in temporary financial relief or other cash flow requirements. By tapping a variety of financial services, the poor are given the chance to boost their household income, increase wealth and property, and considerably reduce their susceptibility to crises and unexpected shocks.

Access to financial services, furthermore, allows for a more balanced diet and better healthcare, which in turn reduces the transmission of diseases. Overall, people living in poverty may more easily plan their future and pay for their children's education. The participation of women in microfinance programs has bolstered their self‐assurance and brought them a step closer in their battle for gender equality.

Microfinance for this reason is more than a form of development aid, as it also promotes self‐determination: poverty‐stricken segments of the population are given access to flexible and affordable financial services and are encouraged to be self‐determined and at the same time develop strategies to gradually work their way out of poverty.12 In recent years, the effects of microfinance with respect to the implementation of the MDGs have mostly manifested themselves in the fight against poverty, the improvement of school education and the health system, as well as in the socio‐economic strengthening of female gender roles.

Thanks to their participation in microfinance programs, the poor can not only increase their income, but at the same time diversify it. This is paramount, as it is the basis for the fight against poverty. Taking a microloan means that business ideas can be funded, which is a boost to national economic growth in its own right. The combination of different financial services – including loans, savings deposits and insurance – facilitates the pooling of funds for business‐related and private purchases. It additionally lowers income fluctuations over prolonged periods of time, so that the level of consumption can be stabilized, even in times of austerity. Microfinance therefore also acts as a buffer to secure both people's professional and private existence in times of adverse fortune.

Various qualitative and quantitative studies reveal a positive influence of microfinance on income and capital. Research by two microfinance institutions, Share Microfin in India and Crecer in Bolivia, suggests that three quarters of Share's clients in India safely attribute the rise in living standards to microfinance, while two thirds of Crecer clients in Bolivia reported a surge in income.13 The variables considered were income, property, capital, housing situation and household expenditure. More than half of these clients managed to escape poverty.

Half of all Share clients further indicated that any surplus in income that was not used to cancel their debts was spent to fund additional expenditures.14 Studies by the World Bank and Grameen Bank in fact yield comparable results that equally document a disproportionate increase in income of program participants. The studies furthermore disclosed that individual success stories of microfinance clients in many cases exert a positive influence on the economy of an entire village, largely because even non‐participating households manage to record an increase in income.15

In many households, additional income is often invested in child education. Various studies have revealed that the children of microfinance clients are more likely to go to school and are less likely to leave school prematurely than children of families that do not seek relief with a microcredit. To further underline the advances achieved in education, many microfinance providers have developed a range of credit and savings services that are tailored to education as a whole. As a result, rates in children starting school have surged significantly and literacy as well as calculation skills in children from participating households have risen distinctly. In addition to this, consistent borrowing results in prolonged periods of school attendance.16

The improvement of healthcare is another declared goal of microfinance. Health issues and diseases often have dire consequences in poor families and lead to higher transmission rates than in wealthier households. In the worst case, death or inability to work may result from any given illness. Ensuing expenditures in connection with ill health have a detrimental effect on income and potential savings, and in many cases lead to income consumption and over‐indebtedness. Microfinance offers suitable products and services for the prevention of illnesses, mostly in the form of health credits that are granted alongside a micro loan. By doing so, microfinance consistently and substantially contributes towards a more balanced diet, better healthcare and the installation of sanitary infrastructure. In partnership with local insurances, MFIs offer their clients life insurances that in the event of death assume liability for outstanding microcredit repayments or funeral expenses.

Modern microfinance has always focused on empowering women. Women in fact very often handle money more responsibly than men, and they also yield a much higher repayment rate. Studies also suggest that women more readily invest higher incomes in the improvement of their family's standard of living and their households than male clients.17 Providing them with access to financial services strengthens their powers of self‐assertion and perseverance and involves them more actively in decision‐making processes within their families and communities in general. Research into the socio‐economic status of women reveals that their participation in microfinance programs leads to an increase in mobility and capital.18

2.3 DOUBLE BOTTOM LINE

The social goals of microfinance are critical in the fight against poverty. Regardless of this, financial profitability and independence remain core aspects. A sustainable and long‐term alignment of the concept facilitates a comprehensive inclusion of the poor into the economic and financial system that goes beyond the limited possibilities of funds with the likes of donations and subsidies. Thanks to microfinance, public and private investors have the possibility to provide financial means without any local infrastructure and thereby to actively combat poverty.

Financial sustainability is key to any long‐term success of a microfinance service provider. Coverage of any incurring costs enables more clients to profit from financial services. Distinctly, equal priority is given to purely financial aspects as well as to social impact on clients. This means that microfinance takes account in equal measure of financial and social services that are mindful of their environmental impact, hence the term “double bottom line”.

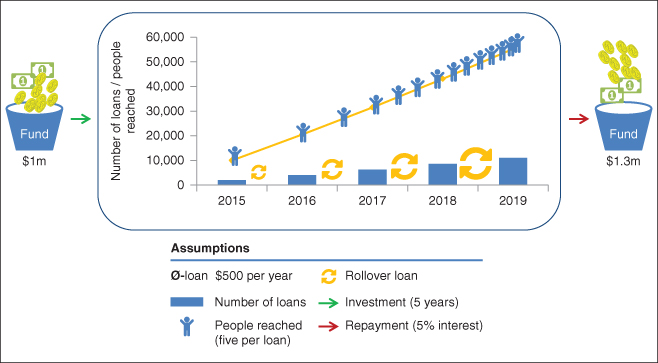

Microfinance is an attractive investment class with a double bottom line. The combination of financial profitability for the investor and social commitment to the client's benefit make an investment in microfinance exceptional and one of its kind; for one thing, investors may generate an attractive and sustainable return by means of their investment. At the same time, it inspires the poor to assume more autonomy and independence, as the funding of their business activities actively combats poverty, which in turn encourages economic stability locally (see Figure 2.3). The term “triple bottom line” is often used when social impact and environmental impact are notably interpreted as separate entities.

FIGURE 2.3 Double Bottom Line

Data Source: BlueOrchard Research

While an investor's financial return is readily measurable, social performance and its impact are subject to interpretation. The Social Performance Task Force (SPTF) defines social performance as the effective translation of a financial service provider organization's mission into practice.19 This comprises sustainability, better services to low‐income segments of the population and those excluded from the financial system, advances in quality and efficiency of financial services, an improvement of clients' economic and social living conditions, as well as social responsibility in the face of the client, employees and affected communities.

Figure 2.4 illustrates the financial and social impact of a $1 million investment. With a 5 per cent return and a five‐year maturity, a $1 million investment will yield $1.3 million. With an average loan of $500 and a one‐year maturity, 2000 micro loans can be issued. Assuming that a total of five people live in the average household, 10,000 people will benefit from these 2000 microcredits. The second year will see 4205 microcredits flowing to 21,025 people – calculating on the basis of a default rate of 3 per cent or less. An investor's capital in fact issues multiple loans: over a period of five years, an investment of $1 million can issue a total of 11,504 microcredits. An investor therefore generates a financial return of $300,000 on the one hand, and supports over 50,000 people in need in developing countries on the other.

FIGURE 2.4 Effects of a $1 Million Investment

2.4 FINANCIAL INCLUSION

The term “financial inclusion” refers to institutions such as banks, non‐bank financial institutions (NBFIs) or NGOs and their resolution to extend their range of financial services to those segments of the population that traditionally do not have access to them. Reaching these mostly rural and underserved members of the population is a feat of innovation in terms of both products and distribution channels. Financial inclusion not only serves the individual client, but also encourages growth and fosters the dynamic development of potentially emerging economies. According to estimates of the World Bank, currently 2 billion people are excluded from the financial system, which means that 25 per cent of the people worldwide are unbanked. In developing countries, virtually half the adult population (46 per cent) have no access to the financial system.20

A look at financial inclusion with respect to levels of income renders an even more dismal picture. More than three quarters of all low‐income adults do not have access to financial services, the reasons being costly access routes to a place where they can open an account, or onerous covenants that render it virtually impossible to access financial services or a simple current or savings account. Financial exclusion goes hand in hand with income inequality: adults in the financially strong OECD countries boast three times as many bank accounts as adults living on a low income.21 Figure 2.5 illustrates unequal financial inclusion according to country: regions such as Latin America, the Caribbean as well as East and South Asia in particular have a comparatively higher inclusion rate into the financial system. Eastern Europe and Central Asia are the midfield players, followed by Sub‐Saharan Africa. The Middle East and Northern Africa features the highest inclusion potential.22

FIGURE 2.5 Financial Inclusion According to Country

Data Source: Demirguc‐Kunt, Klapper, Singer and van Oudheusden (2015)

Access to the financial system and sustainable financial services is of utmost importance and exerts a positive impact on various levels of society, most notably on all households and enterprises, as well as on overall economic growth.

Access to financial systems allows households, i.e. individuals and entire families, to build capital and deposit it safely. It fosters a sustainable and long‐term approach in dealing with recurring risks and consumption smoothing in equal measure. By means of their economic contribution, micro entrepreneurs achieve higher social recognition, which is undoubtedly the source of more self‐confidence and security.

Micro‐, small‐ and medium‐sized enterprises (MSMEs) are the major employers in many low‐pay countries. They equally profit from financial integration. Often the growth of these enterprises is severely limited due to restricted access to capital and savings deposits, mostly as a result of a lack of funds to invest in capital assets or additional work force. With the help of savings deposits, adequate payment transactions and insurance products, businesses can manage their risks more sensibly and profitably.

Financial integration and the development into an integrated, universal financial system positively influence economic growth and contribute towards amending income inequality. On the initiative of the G‐20, and their declaration of financial integration as a pressing economic policy, the Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion (GPFI) was set up. The GPFI is the result of the collaboration between the World Bank, the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP). Its declared goal is to greatly facilitate access to financial systems worldwide, particularly for segments of the population with a low income.

In many cases, due to soaring transaction costs, people at the bottom of the economic pyramid are beyond consideration as prospective clients for formal financial service providers (see Figure 2.6). The only option left for the poor is to borrow from informal financial service providers such as money lenders or relatives, often at hugely exaggerated interest rates. Numerous micro entrepreneurs are unable to develop their businesses further or improve their living standards as a frequent result of funding difficulties. Microfinance institutions bridge this gap and thereby manage to reach client groups that are yet to be included into the financial system. Hence, investments in microfinance foster a systematic development of the financial sectors in developing countries. The financial markets in developing countries, however, are still reasonably small in comparison to those in industrialized countries.

FIGURE 2.6 Access to a Bank Account Depending on Income Class

Data Source: World Bank (2015a)

The steady increase in new client groups and the competition among MFIs may well lead to a growth rate of these small markets in the near future that will surpass the GDP of the countries in question.23

2.5 MARKET PARTICIPANTS

Ultimately, who profits from the concept of microfinance, and are there substantial differences between the different interest groups? The answer is remarkably simple: given professional and transparent conduct, all parties will benefit from microfinance; that is, individual borrowers, women, households, enterprises, microfinance service providers, microfinance vehicles, governments, sponsors and the economy as a whole. The following takes a detailed look at the different interest groups and the way they profit from microfinance.

Individuals and Micro Enterprises

As mentioned above, microfinance provides the poor with loans and access to financial services. This enables them to fund their investments. Savings services, too, are becoming increasingly important, even more so as they allow for wealth building that permits consumption smoothing but also serves as collateral for loans from formal financial services providers. Women experience the strengthening of their roles in the socio‐economic framework and are thus better equipped to live autonomous and independent lives. Microfinance also improves access to education and healthcare and improves living standards. Businesses can fund their organic growth and create new employment thanks to microfinance.

MFIs, MIVs and Investors

Microfinance has advanced in record time over the last few years, and the original idea of the microloan has long been overhauled and has grown into the comprehensive microfinance we know today, with a vast range of financial services. The provision of such financial services to poor segments of the population in itself justifies the benefit of microfinance institutions. The collection of clients' savings allows for continuing growth of sustainable MFIs and reduces their dependency on governments, sponsors and loan providers.

MIVs profit from a regular fixed income from interest payments that are generated by loans that flow to MFIs. Investors, too, benefit from the properties of microfinance: their investments in MFIs give them access to an attractive investment class with stable and sustainable returns and, perhaps more importantly, they make an important contribution towards the fight against poverty in the world.

Governments and Sponsors

Local governments and sponsors benefit from microfinance, because the financial means that are generated can be used for further developmental projects. Governments profit on top of this from lower transfer payments and additional tax returns that are generated as a result of higher incomes and business profits. Microfinance boosts the efficiency of the economic system, which in turn has a positive influence on society as a whole.

The Economy

Growth of local microfinance sectors yields a positive influence on the development of any national financial system. Competitive constraints force MFIs into high market efficiency and safeguard their clients' needs sustainably. The mobilization of capital and ensuing investment activity generate growth within the national economy. An increasing number of people find their way out of poverty with the help of microfinance. Their business acumen raises the national income steadily.

2.6 IMPACT INVESTING

For a better understanding of the defined goals in microfinance and its suitable and deserved positioning in the order of the investment universe, impact investment needs to be differentiated from philanthropic and conventional investment (see Figure 2.7). These concepts are often muddled up and lack a clear‐cut distinction with respect to motivation, impact and economic goals. It is of vital importance for investors in particular to know how they differ to avoid any misunderstandings.

FIGURE 2.7 Differentiation of Impact Investing

Data Source: Impactspace (2014)

Conventional Investments

Traditional investing employs capital in order to achieve a financial return. Social and environmental aspects are not focal points of a conventional investment strategy. Three different forms of investing can be distinguished: mainstream investing comprises all investments in businesses, regardless of their social or environmental impact. Contrary to that, socially neutral investing (SNI) can be divided into two categories: socially responsible investment (SRI) and sustainable investment (SI) (see Figure 2.8). SRI applies an investment filter that excludes investing in ethically problematic enterprises; investments in tobacco, alcohol and weapons production or in the gambling industry are consequently not encouraged. Sustainable investing identifies investment decisions with the help of a positive filter. It distinguishes businesses with a sustainable corporate governance that involve social and environmental aspects into their business activities. It considers companies, for instance, that are active in the field of sustainable energy production or with an environmentally friendly and socially responsible production run.

FIGURE 2.8 Filter for Conventional, Sustainable Investment Decisions

Data Source: Geczy, Stambaugh and Levin (2005); Meyer (2013); Renneboog, Jenke and Zhang (2008); Staub‐Bisang (2011)

Impact Investing

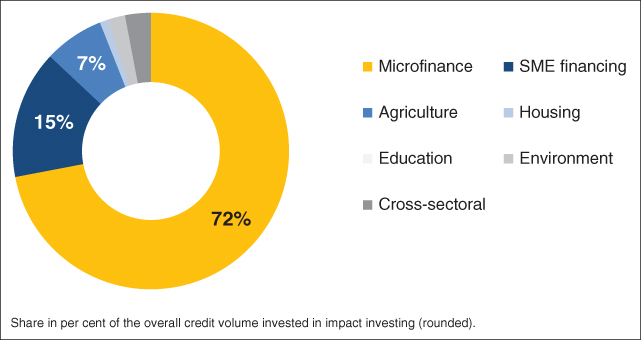

While conventional and philanthropic forms of investment only consider financial or social impact respectively, impact investing is a combination of both approaches. Impact investing uses capital in order to generate social and environmental results as well as financial returns. The focus may meander between financial and social return.24 Judging by the growing popularity and steady growth of impact investing, the double bottom line has become a buzzword and well‐known concept (see Figure 2.9). Apart from microfinance, impact investing includes topics such as education, health, food security, supply channels and infrastructure.

FIGURE 2.9 Topics Impact Investing

Data Source: Forum Nachhaltige Geldanlagen (2015)

Philanthropy

Impact investing denotes the socially motivated delivery of financial means with the intention to create a maximum social and environmental return (see Figure 2.10). The financial aspect of such investments fades into the background. We differentiate between venture philanthropy and donations to charity. Venture philanthropy has its focus on the funding of socially responsible enterprises that partly or entirely generate their income based on business activities.25 Charitable donations, however, fund non‐profit organizations that depend on those contributions.

FIGURE 2.10 Growth of Sustainable Investment Strategies (Assets under Management in EUR Billions)

Data Source: Forum Nachhaltige Geldanlagen (2015)

2.7 PRELIMINARY CONCLUSIONS

Microfinance is instrumental in the fight against poverty and in fostering financial integration of destitute and low‐income segments of society. More narrowly speaking, the concept of microfinance refers to the delivery of financial services to low‐income clients who lack the necessary funds for business activities. These financial services comprise the granting of loans, the collection of savings deposits as well as insurance and payment services. Beyond that, many MFIs offer a variety of non‐financial services that support microfinance clients' endeavors to establish business activities and more generally offer assistance in coping with day‐to‐day issues of life. Microfinance substantially contributed towards attaining the MDGs. Thanks to microfinance, major steps have been made over the last few years in the fight against poverty, the improvement of education and healthcare, as well as the socio‐economic role of women.

Beyond all this, microfinance is an attractive investment class for investors with a double bottom line: it successfully combines profitability and social commitment. Investors, MIVs and microfinance institutions can generate sustainable and attractive revenues through microfinance. More importantly, however, microfinance encourages autonomy and independence for those at the bottom end of the economic pyramid, by funding their business activities and combatting poverty in the long run.

Microfinance is a combination of conventional and philanthropic forms of investment. It is a fusion of two thus far separately regarded investment disciplines and manages to unite the goals of both approaches – financial return and social wealth – in one unique concept.