CHAPTER 3

The Microfinance Value Chain

Give a man a fish, [and] he'll eat for a day. Give a woman microcredit, [and] she, her husband, her children, and her extended family will eat for a lifetime.

Bono1

Highly specialized protagonists along the value chain of microfinance ensure an efficient distribution of the financial means to the various micro entrepreneurs.

Everyone involved, from investor to micro entrepreneur, is subject to supervision or is at least affected by this supervision in one way or another.

3.1 THE PROTAGONISTS AND THEIR TASKS

The microfinance sector has become professionalized over the years, which is amply reflected in the fragmentation of the value chain in highly specialized protagonists. Specialization of the different service providers along the value chain efficiently allocates financial means and at the same time raises the overall quality of the services on each and every level of the value added.

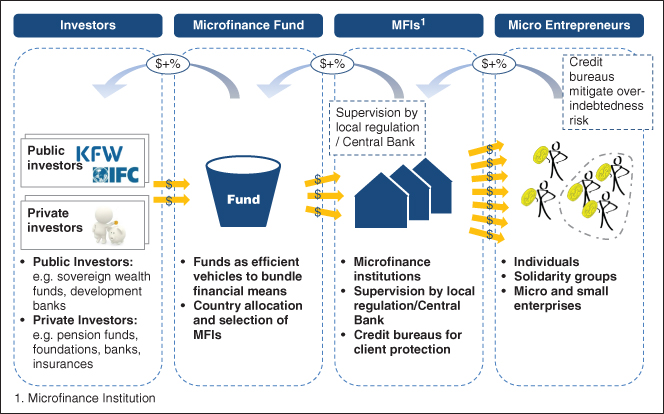

The value chain of microfinance typically consists of four levels (see Figure 3.1). Funds provided by the investors are bundled into fund structures to be supervised by a microfinance administrator. The administrator identifies, analyzes, selects and consequently supervises those MFIs that are the recipients of equity or debt capital. The MFIs in turn are in charge of issuing microloans to their clients and therefore perform all the associated actions.

FIGURE 3.1 The Microfinance Value Chain

Source: BlueOrchard Research

Investors

Microfinance investors can largely be attributed to two groups. On the one hand there are public investors – mainly development banks such as the World Bank and Germany's Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW) – the recipients of financial funds from individual or several countries. Private investors, on the other hand, are becoming increasingly important. Private investors are large institutional investors such as pension funds, foundations, banks, insurance companies, but also private persons.

Microfinance Funds and Fund Administrators

Mutual funds bundle financial means effectively and provide even investors with considerably small investment volumes with a broad range of diversification. Due to the concentration of equity in a fund structure, for instance, more favorable terms for currency hedging and further transactions may be negotiated, as opposed to each individual investor having to take matters into their own hands. The fund administrator, moreover, ensures professional management of the finances and has the experience to select potential MFIs, invest in them and monitor them. The MFIs in turn benefit from the fact that instead of a multitude of individual investors they have a singular fund as their partner.

Microfinance Institutions

MFIs are the direct and personal points of contact for micro entrepreneurs and therefore bridge the gap between the clients and the funds. They are local financial intermediaries with varying legal structures and they are in charge of micro entrepreneur customer care. As one of their most important tasks, MFIs assess their clients' creditworthiness, grant and supervise loans, manage customer relationships and provide training to micro entrepreneurs.

Micro Entrepreneurs

Micro entrepreneurs are the recipients of microloans and usually are among the poorest of the poor. In general, micro entrepreneurs are granted loans in order to set up their business or expand it. These means are therefore invested in productive activities that secure repayment. This is even more important as these micro entrepreneurs are in most cases unable to provide financial collateral and their ability to repay the loan solely depends on their economic success.

3.2 REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT

The financial industry is strongly regulated, not least because of the international financial crisis that started in the wake of the events in the fall of 2008. Investment in microfinance is by no means an exception. Along the entire value chain each and every protagonist is carefully monitored, be it directly or indirectly. It is a much underrated fact that requires further scrutiny.

On the investor side, regulation differentiates between institutional and individual private investors. Institutional investors such as pension funds are often directly subjected to a regulatory authority that should ensure a meticulous administration and management of the funds entrusted to any given pension fund. When it comes to private investors, however, the regulator takes a more direct approach by supervising the distribution channels of the funds – for instance, banks or independent asset managers. In both cases, client protection is of utmost importance, i.e. investors should only invest within the limits of their personal risk profile. MIVs are readily available in most countries, both for institutional and private investors.2

The next level of the value chain – the funds and the fund administrators – is subject to tight supervision as well. Regulation of these entities generally is enforced by the financial markets authority.3 The regulatory approach is more than evident in the fact that the simple launch of a mutual fund is subject to permit. The regulator must mandatorily grant permission for the launch of a fund and as a rule stipulates rigorous terms and conditions that the funds administrator has to abide by. The fund's management as such is an activity that is subject to permit in most countries and is governed by close and unremitting supervision. Regulatory authorities are particularly strict when it comes to a funds manager's substance. In many cases, specific standards in terms of both quality and quantity have to be obeyed regarding personnel. Furthermore, internal processes have to be sufficiently documented and remuneration systems must often comply with specific standards.

In the value chain of microfinance, MFIs are of great importance. They are the gateway to the client and therefore carry considerable responsibility, a fact that has led to particularly rigid and comprehensive regulation for MFIs. However, tight regulation can also incur considerable costs. Exaggerated regulation may markedly have two significant downsides for micro entrepreneurs. Firstly, regulation of the MFIs raises prices for the clients. Secondly, regulation may constitute an insurmountable challenge when it comes to market entry, which deters new service providers or even obstructs the introduction of new products for the benefit of micro entrepreneurs. This would inevitably lead to less competition among established MFIs and in all likelihood result in rising product costs. In addition to this, MFIs differ considerably in terms of their legal structures and their range of services. A universal approach is therefore hardly beneficial. The regulatory authorities should gauge the costs incurred by regulation and contrast their results with the overall goals of microfinance.4 Today, international standards have been established that manage to deal with the challenges mentioned above. They principally tackle issues such as investment, minimal capital requirements, capital adequacy, liquidity requirements and customer protection (see Chapter 5.5).

Credit bureaus are another important instrument for credit users and customer protection. They collect information on previously issued loans. Loan offices are present in most significant microfinance markets today. In a first move, the regulator often compiles a loan register. Increasing market maturity, however, will also favor the emergence of private service providers. The information on a loan register typically comprises entries such as the type of loan, maturity, amount of loan and possible instances of late payment or payment default. Private loan offices will also gather information on their clients' payment performance – for instance on the local retail trade or whether their electricity and water bills have been paid. This allows for an even better appraisal of a borrower's creditworthiness (see Chapter 5.5).

3.3 DEVELOPMENT FINANCE INSTITUTIONS

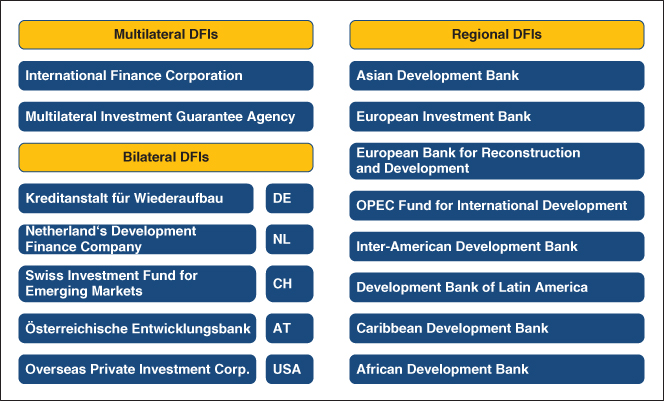

Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) are financial institutions that belong to the realm between public development aid and private investments. DFIs are governmental or semi‐governmental organizations and may be of a bilateral or multilateral nature (see Figure 3.2). Bilateral DFIs are governed by a single country. Examples are the German KfW, the Dutch Financierings‐Maatschappij voor Ontwikkelingslanden (FMO), the Swiss Investment Fund for Emerging Markets (SIFEM) and the Austrian Development Bank (OeEB). Regional DFIs are communal institutions of several countries of a particular region – for example in Europe the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) or the Asian Development Bank (ADB). There are the multilateral DFIs that are positioned as international organizations. The best known example probably is the International Finance Corporation (IFC) that forms part of the World Bank.5

FIGURE 3.2 Selected Development Finance Institutions (DFIs)

DFIs play a central and influential role in the fight against global issues such as poverty or climate change and are an integral part of the microfinance sector. In many cases, DFIs furnish the means for investments in developing countries. Typically, these are investments that still lack sufficient numbers of private investors, or projects to which private persons have limited access. Their mission, among other goals, is to create an investment environment for commercial investors – all the more reason for DFIs to closely collaborate with private organizations.6

DFIs invest in developing countries in three ways:7

- They fund local financial institutions, which in turn finance local micro entrepreneurs and SMEs.

- They provide funds to specialized private mutual funds to enable them to invest in local projects, businesses and institutions.

- They invest in local businesses and projects directly.

DFIs go to great lengths to avoid direct competition with private investors. For this reason, their funding usually is not free of charge, but should yield a financial return. In some cases, DFIs manage to profit from their first mover advantage and create attractive returns. Those proceeds, however, are seldom distributed but generally reinvested in new projects.

As explained above, DFIs are weighty investors of specialized microfinance funds. Moreover, DFIs also invest directly in individual MFIs. Private investors thereby have the possibility to invest hand in hand with DFIs and in this manner profit from a risk‐sharing mechanism.8

Beyond their basic funding services, DFIs often also provide services and equipment for technical assistance (TA). These services provide a comprehensive approach in a bid to further local institutions. TA might mean that an MFI may choose to make use of a DFI's consultancy services in matters concerning product development or design and improvement of business activities. In return, an MFI will usually in reasonable measure share responsibility for the costs incurred.9

Alongside development institutions, an increasing number of local governmental institutions have been known to position themselves on the market to improve the geopolitical stability of their region. Microfinance profits from the proximity to lenders of capital that such models provide, and by means of this, new paths open for further development in these countries.

3.4 MARKET OVERVIEW

The turn of the millennium has seen an ever‐increasing emergence of impact investment funds and thereby a surge of fund administrators and consultants (see Figure 3.3).

FIGURE 3.3 Selected Managers of Microfinance Investment Vehicles

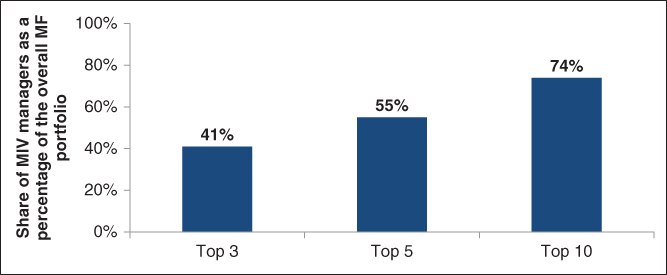

A look at assets under management (AUM) reveals a significantly concentrated market. Figure 3.4 illustrates the share of microfinance fund managers in the total microfinance portfolio worldwide. The three largest fund providers manage 43 per cent of all AUM in microfinance. The five largest alone constitute more than 50 per cent, and the ten largest MIV administrators have a combined market share of almost 80 per cent.

FIGURE 3.4 Concentration of MIV Managers

Data Source: Symbiotics (2015)

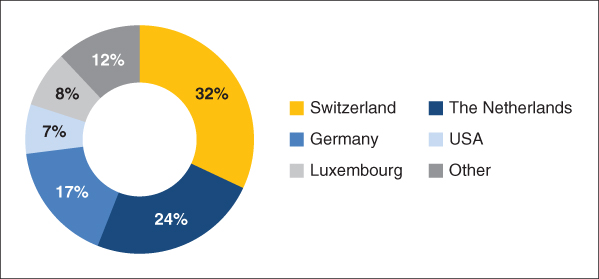

With providers such as BlueOrchard Finance, ResponsAbility and Symbiotics, Switzerland has more than one string to its bow in the field of impact investing. More than 30 per cent of all assets allocated in impact investing worldwide are either managed from Switzerland or monitored in an advisory capacity respectively (see Figure 3.5). Beyond Switzerland, another microfinance market has established itself in the tri‐border area between Germany (Finance in Motion), the Netherlands (Oikocredit, Triodos, Triple Jump) and Belgium (Incofin).

FIGURE 3.5 Managed AUM in Microfinance, According to Location of MIV Administrators

Data Source: Symbiotics (2015)

3.5 GENEVA: BIRTHPLACE OF MODERN MICROFINANCE

In Geneva in the late 1990s, the vision of a microfinance fund was born. The breeding ground for such productive thoughts was generated by the innovative partnership of the United Nations (UN), the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) and the private banking sector.

Circumstances

The exceptional circumstances in Geneva make the city a laboratory of sustainable economy. What are the reasons for this?10

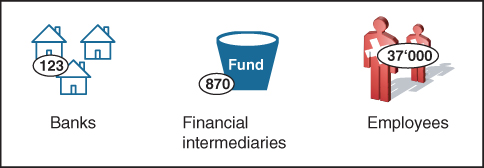

- Geneva is one of the most competitive financial centers in the world and a leader in the realm of transnational asset management. With its more than 200 years of tradition and history, the Geneva financial sector is renowned for asset management and its range of personalized services (see Figure 3.6).

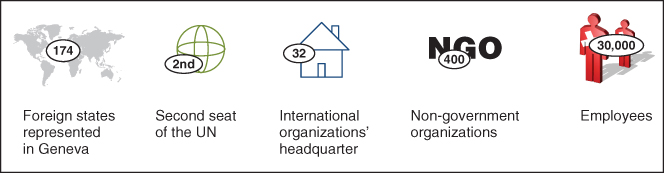

- The UN has their second subsidiary headquarters in Geneva, which has had its appeal for international organizations and non‐governmental organizations (NGOs) for over a century.11 Today, more than 30 influential international organizations have their headquarters in Geneva, not to forget the over 400 NGOs that advise the UN (see Figure 3.7).

- Switzerland is known as the epitome of innovation and has been leading the global innovation rankings for years. Such innovative spirit has propelled Switzerland to acquire a singular level of expertise in fields such as industry, biotechnology and in the financial sector – a knowledge that is travelling across the globe.

FIGURE 3.6 Geneva Financial Center

Data Source: Sustainable Finance Geneva (2014)

FIGURE 3.7 International Geneva

Data Source: Sustainable Finance Geneva (2014)

The fusion of two worlds – financial economy and international development – combined with the Swiss innovative spirit, makes Geneva a unique breeding ground and workshop of financial economy. For this reason, in Geneva many sustainable financial products, concepts and instruments of global relevance were conceived.

Switzerland counts 200 organizations that are actively involved in the sustainable financial economy (owners of capital, asset managers, investment specialists and so on). Moreover, the first global indexes for stocks of sustainable businesses (Dow Jones Sustainability Index – DJSI) and for microfinance (SMX – Symbiotics Microfinance Index) – used worldwide as reference indexes today – both have their origin in Switzerland.

The Emergence of Microfinance as an Asset Class

Geneva owes its role as a global leader to the cooperation of several specialized UN agencies with visionary private bankers – notably the International Labour Organization (ILO) and UNCTAD.

In 1997, the UN General Assembly decided to make 2005 the year of microcredit. As a result of this decision, the UNCTAD microcredit unit began its work on several projects in Geneva, with the aim of increasing transparency in the sector and fostering private financing for microfinance. The first milestone was set in 1998 with the introduction of the Dexia Microcredit Fund. The year 2000 saw the launch of a virtual microfinance market and a microfinance information platform devised by Infobahn, a Geneva‐based IT company. A year later, the fund manager BlueOrchard was founded in Geneva. With the approach of the year of microcredit, BlueOrchard managed to raise an increasing amount of funds for its very first fund, mainly with the help of various Geneva‐based asset managers and the structuring of a product by J.P. Morgan in New York, for which the US government acted as a guarantor.

These successes amply proved to the world that the combination of commercial financial economy and aid for poor segments of the population could indeed be a winning formula. In the following years, other Swiss fund managers established themselves alongside BlueOrchard. Their unique knowledge allows them to assume a leading position on the global microfinance market. In 2003, the company ResponsAbility was founded in Zurich, and a year later Symbiotics was launched in Geneva.

With its commitment to human rights and peace, Geneva has forged an impeccable international reputation for itself. Organizations such as the World Trade Organization (WTO), UNCTAD and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) are a reservoir of the condensed knowledge of experts in both economy and finance.

The United Nations Finance Initiative (UNEP FI) was launched in the wake of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. The foundation of this specific initiative within UNEP relies on the significant role of the financial economy for the promotion of sustainable development. Banks and capital markets, which finance the economy, have the power as well as the responsibility to foster economically sustainable models. UNEP FI is a public–private partnership that aims to integrate the financial aspects of sustainable and social topics into financial institutions. One of its most impressive achievements is the introduction of the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (UN PRI or PRI for short). The UN General Secretary at the time, Kofi Annan, launched the initiative in 2005. UNEP FI and UN Global Compact – which argues the case for sustainable and ethical corporate governance – synchronize their development. Financial institutions that ratify the six PRIs commit themselves to the common good of society. This was a truly extraordinary feat of ingenuity on the part of the UN and Geneva.

The PRIs have been a success story. To this day, more than 1300 asset managers and professional service providers have ratified them.12 They thereby pledge to document their development for increased sustainability and to integrate the principles of sustainable investment into their daily business. The PRIs are set to permeate the entire industry.

The UNEP FI also cooperates with other institutions for synergy effects; for instance, the collaboration with the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD), an association of companies committed to mutual topics in connection with sustainable development, or their cooperation with the World Economic Forum (WEF), the advocate of sustainability in economic, environmental and health policy worldwide.

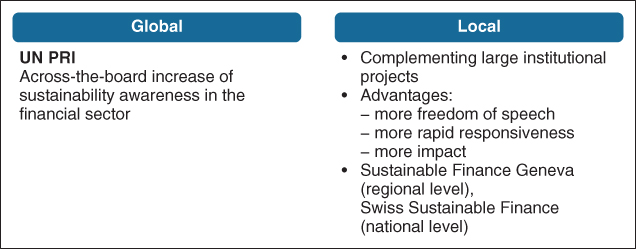

The UN PRIs are one of the most significant initiatives for sustainability in the financial sector. Their top‐down approach increases awareness in terms of sustainability in the financial sector on a large scale (see Figure 3.8). At the same time, national and local initiatives complement the large institutional PRI projects (bottom‐up approach). The advantages are evident: more freedom of speech, more rapid responsiveness and more impact, thanks to their proximity to low‐income segments of the population.

FIGURE 3.8 Sustainability Initiatives in the Financial Sector

In 2008, 15 specialists pooled their energies and launched Sustainable Finance Geneva (SFG), a platform that allows interest groups to meet and exchange. Non‐profit SFG fosters innovation and development in a sustainable financial economy. Its goal is to unite under one roof a multitude of personalities and collect a wealth of experience from fields such as asset management, fund management, microfinance, international organizations, as well as environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria and philanthropy. SFG was developed with local organizations, such as the Genevan authorities and the Genève Place Financière, in order to further establish and continue to advertise Geneva and Switzerland as the number one sustainable center of the financial economy. SFG focuses on a regular exchange of information and conducts studies, but at the same time organizes numerous conferences and discussions with national and international experts.

The launching of the Swiss Sustainable Finance (SSF) platform in Zurich in 2014 hails a project on a national level. SSF aims at positioning and representing the topic nationally, for instance in dealing with various federal authorities. SFG is a networking partner of SSF. Both organizations collaborate closely and coordinate their activities.

3.6 PRELIMINARY CONCLUSIONS

Knowledge of the protagonists, and more importantly their roles along the value chain, is indispensable for a thorough understanding of microfinance. Their highly specialized activities lead to a bundling of financial means that in turn allow micro entrepreneurs to have access to valuable capital.

Investors provide microfinance funds with financial resources that fund managers or advisors invest in selected microfinance institutions. By doing so, MFIs can issue microloans to their clients.

More than a third of the funds invested in the entire microfinance sector are being managed from Switzerland. The three largest fund providers manage more than 40 per cent of the total AUM in microfinance. The vision to launch a microfinance fund was generated in Geneva, in the late 1990s. Geneva is one of the most competitive finance centers in the world and boasts a high presence of international organizations and NGOs. The close cooperation of these organizations with the financial sector, as well as the wealth of innovative force in Switzerland, make Geneva a laboratory for international financial economy. The center of the United Nations for sustainable financial economy in Geneva led to the foundation of the UN PRI, an admirably successful initiative established in the name of sustainability and responsibility in the financial sector.