CHAPTER 6

Lending Methodologies

The entire bank is built on trust.

Muhammad Yunus1

Lending in microfinance is based on trust.

Group loans, mutual monitoring and a progressive loan structure inspire trust among borrowers themselves on the one hand, and borrowers and MFIs on the other. Borrowers are prepared to redeem their loans to be able to have continuous access to capital.

Socio‐economic factors such as location and gender also have an impact on the success of a micro entrepreneur's business activity.

6.1 TRADITIONAL CREDIT THEORY AND MICROFINANCE

Traditional credit theory is based on Stiglitz and Weiss's model of credit rationing.2 They examined credit rationing in markets with imperfect information. Generally, high‐risk borrowers pay higher interest rates and must provide higher collateral as their probability of default is higher than in low‐risk borrowers. Credit rationing thus occurs when borrowers with a low degree of creditworthiness are willing to pay interest that is above the equilibrium interest rate at which banks issue loans. These borrowers, however, remain unserved because despite the elevated interest rate, the bank will refuse to take the higher risk of probability of default. Interest rate and collateral are in this case used as a means of selection to counteract issues with moral hazard, adverse selection and asymmetrical information. This issue is known as the principal–agent problem, as illustrated in Figure 6.1. It is mitigated by credit ratings that influence the two means of selection, i.e. interest rate and collateral. High creditworthiness is rewarded with low interest rates, borrowers with low creditworthiness will have to pay higher interest rates to compensate for their increased default risk; the higher the default rate, the greater the demands on collateral. Financial collateral has two effects. It makes loans affordable for borrowers with a high default rate. For lenders, however, it offers compensation in cases of repayment issues.

FIGURE 6.1 The Principal–Agent Problem

Microfinance, however, is a concept that does not follow the traditional credit theory mentioned above. The principal–agent problem is not reduced by financial collateral, but rather with the help of a sense of security such as trust.3 Financial resources are in this case lent to a network of trust consisting of families, friends and strangers, all supporting each other to have access to loans.4 Let us not forget that micro entrepreneurs usually have one chance to access capital and therefore must proceed swiftly and carefully. If they default on one occasion, applying for another loan will be virtually impossible. In contrast, in industrial countries people are granted loans repeatedly by simply providing certain financial securities. Developing countries, however, often lack a reliable legal structure that settles property rights. In many cases, it is therefore impossible to establish ownership, let alone transform it into capital. In a country where no one can identify exactly what is owned by whom, property cannot simply be transformed into capital or be divided into stocks. As a result of this lack of framework, the value of property or ownership is impossible to determine. De Soto refers to this a “dead capital.”5 Lending methodology certainly plays an important part in the assessment of default risk, but so do socio‐economic factors such as market proximity, the potential for activities that add value, and gender.

6.2 LENDING METHODOLOGIES

The microfinance sector knows several lending methodologies. Key elements in all of them are a collective duty of repayment for group loans, mutual monitoring, progressive lending and regular meetings with the MFI in charge.6

Group Loans

Lending in microfinance owes much of its success to group lending. Each individual subsidiarily vouches for the other members of the group and their repayments. Culturally, this means that Asian clients in particular lose face when they fail to repay their loans. As a result, borrowers support each other and share their knowledge and skills. This reduces the amount of private information that the lender has no access to. This mutual obligation to repay almost completely eliminates the risk of default.7

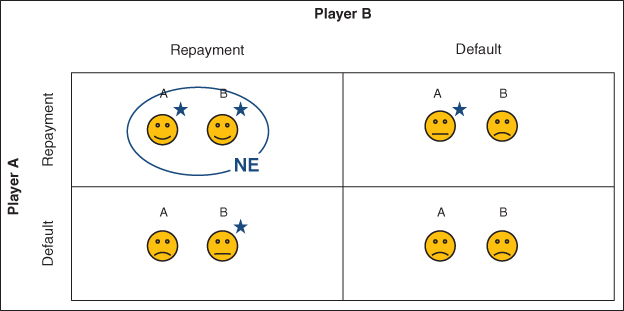

The characteristics of collective repayment can be described by means of a game theory scenario. Figure 6.2 displays the different moods of two borrowers who have taken out a group loan. The mood of player A is illustrated on the left, player B is seen on the right. The Nash equilibrium (NE) occurs if each player chooses the strategy from which he or she benefits the most, despite the fact that they know their opponents' best strategy and motivation.8 It therefore takes into account the decisions of the other players, as long the other party's decisions remain unaltered, and describes the best possible reaction of both players, bearing this knowledge in mind. For our example, this means that the best option for both players A and B always is to repay the loan.

FIGURE 6.2 Group Loans and Game Theory

If player A repays the entire loan, player B had better redeem his or her loan as well. If player A slips into default, player B's best option definitely is to clear both of their debts. Repaying both of their debts still puts player B in a better position than without payment, as despite the fact that she or he has to bear the costs for player B's debts, player B will in all likelihood proceed with the repayment to secure access to financial resources in the long run, and not lose face. Non‐repayments by both participants, therefore, are never an optimal solution. This game theory example shows that borrowers are determined to put their business ideas into action in a profitable manner and to manage their finances on their own accord, so as to repay their loans.

Mutual Monitoring

Mutual monitoring, with or without repayment liability, boosts the learning effect among borrowers, as they share their experiences and keep each other up to date. Their mutual support and monitoring secures timely payments and largely avoids default. Successful borrowers want to take out further loans and therefore educate and train other members of their group with potential repayment issues.9

Progressive Loans

In progressive lending, successful repayment allows for better terms in a borrower's subsequent loan. The progressive loan structure method reveals that learning effects have a positive influence on rates of repayment. Micro entrepreneurs who have successfully repaid their first, second and subsequent loan will ascend along the progressive loan structure. A higher level therefore means more stable and reliable repayment. In first loans the rate of repayment is generally more volatile, as default is more likely and borrowers are still in the process of acquiring new entrepreneurial and financial skills. Members who have advanced to a higher level in the progressive loan structure reveal a significantly more stable and notably better rate of repayment.10

Regular Meetings with MFIs

Frequent meetings with the MFI – which is also when interest is collected – allow for a more accurate assessment and monitoring of a borrower's business projects. MFIs can provide their clients with valuable information regarding the management of their assets, an improvement of the proceedings involved, and other useful skills. This enables loan officers to nip potential problems in the bud, before their clients' situation may even deteriorate.

6.3 SOCIO‐ECONOMIC FACTORS

Socio‐economic factors are decisive when it comes to lending in the microfinance sector, as they influence the generation of cash flows and with it the loan repayments. Particularly relevant are location and gender.

Urban vs. Rural Population

A look at the microfinance market globally reveals that about half of all loans are issued to clients in urban areas, 45 per cent to clients living in rural and 5 per cent to those living in semi‐urban areas. Accessibility and market presence thereby play an important role.

As a rule, borrowers from urban areas have an advantage over rural clients. Information is more readily available and activities that add value find a wider clientele. This increases profitability in borrowers. Market proximity has a positive influence on the borrowers' cash flows that are used to redeem their interest and repay their loan. MFIs that grant loans in rural areas have much greater challenges to meet. For micro entrepreneurs in rural areas, going to market is considerably more difficult, as they will try to lower their transport costs per item sold. Consequently, they will only take their goods to market when they have produced sufficient quantities. Farmers, for instance, will only generate cash flows after their harvest. Interest cannot for this matter be paid on a regular basis, but payments are dictated by the maturity of their crops. Meeting these challenges and access to markets are highly influential when it comes to steadily increasing repayment rates in borrowers.11

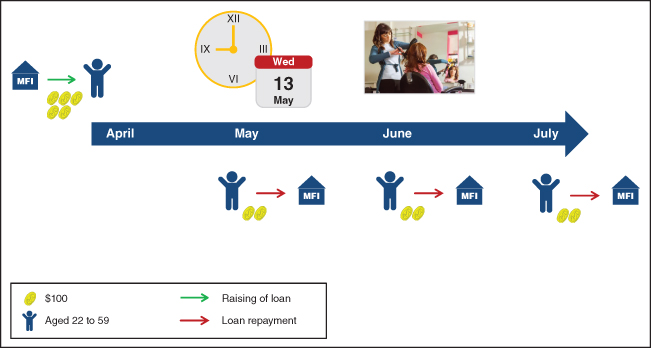

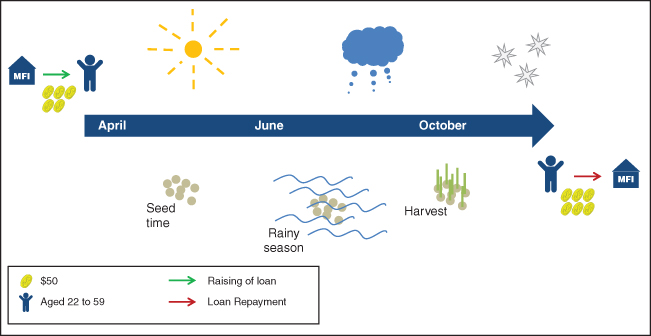

MFIs also provide products to thwart the irregular cash flows of a market gardener, for example. Tameer Bank, an MFI in Pakistan, provides more than 20 different microloans, most notably the Tameer Karobar Loan (see Figure 6.3) and the Agri Group Loan (see Figure 6.4).

FIGURE 6.3 Example of a Micro Loan – Tameer Karobar Loan

Data Source: Tameer Bank

FIGURE 6.4 Example of an Agricultural Loan – Agri Group Loan

Data Source: Tameer Bank

The Tameer Karobar Loan is a tailor‐made loan for micro entrepreneurs, designed to fund circulating assets and make investments. The loan is repaid monthly, in equal installments. As this loan is based on monthly installments, it is only ever suitable for micro enterprises that manage to generate regular cash flows with their business model – for example, a micro entrepreneur who lives in the city and owns a hair salon, whose regular clientele will enable them to redeem their loan.

A vegetable farmer living in the hinterland of Pakistan would typically apply for a loan from Agri Group Loan. In Pakistan, this group loan is issued to farmers exclusively. Unlike with the Tameer Karobar Loan, the Agri Group Loan demands a one‐off repayment of the entire loan including interest at the end of its term. The fact that no payments have to be made during the life of a loan is a concession to the farmers, as several months elapse between seedtime and harvest, and cash flows can only be generated when the goods are sold. With no savings on hand, grain growers are simply unable to repay their loans in weekly or monthly installments.12

These examples illustrate that MFIs have developed products that are made to measure for specific groups of clients by making allowances for irregular incomes. A client's creditworthiness should remain unaffected as a business model that only generates incomes every other month may well be as successful as a popular hair salon downtown.

Gender

More than two thirds of all loans are given to women, less than a third flows to men. Evidently there is a preference of female over male borrowers. This discrimination is more likely to be found on the supply side than on the demand side. Practice reveals that female borrowers carry less of a risk than men. What are the reasons for this?

There are many different reasons why women are preferable clients. Women exhibit certain characteristics that reduce the possibility of loan default. Their boundaries of shame are set much lower and they are more risk‐averse than men.

Risk‐averse properties in women are a sense of modesty, discretion and discipline. These properties root in cultural customs such as the fact that women are guardians of entire family clans and their ensuing roles as custodians of the family's funds. Women use their income to meet their children's needs, for their education, food and healthcare. Men, on the contrary, stretch their income to fund personal requirements such as their entertainment and status symbols.13

Against the cultural backdrop that borrowers lose face in their societies if they fail to repay their loans, women have been revealed to have a lower boundary of shame. For this reason, women are more susceptible to moral and social pressure than men and they more readily accept help. They share information, generally communicate more openly about their problems and regularly attend MFI meetings.

All in all, women who start their own business or seek financial resources are more risk‐averse. They are thus more cooperative, and proceed more prudently and less opportunistically in dealing with their family's finances, which reduces information asymmetries and moral hazard adverse selection for their lender. Women are therefore less likely to seek a loan beyond their repayment capabilities.14

For these three reasons, loans given to women yield a lower rate of de‐fault than those given to men.15 Higher risk aversion admittedly leads to an increase in repayment rate, but it may, however, not necessarily have a positive impact on an MFI's profitability. For one reason: albeit women reveal a lower average credit volume than men, an MFI will incur virtually the same operating costs for high and low volumes. MFIs therefore are challenged to bring the lower risk of default in women in line with their profitability in order to strike a balance between lending methodologies and socio‐economic factors.16

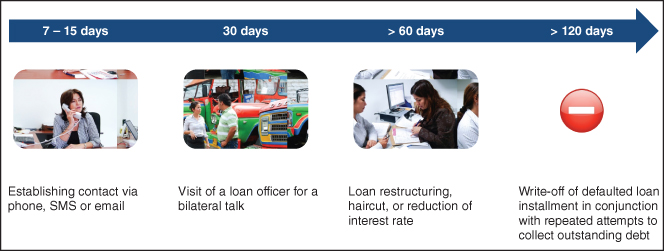

6.4 LATE PAYMENTS AND OVER‐INDEBTEDNESS OF CLIENTS

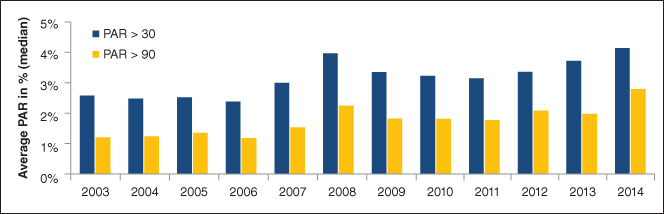

The portfolio at risk (PAR) is generally very low. It is a ratio that singles out the loans in the microfinance sector most at risk of default. Only 1–2 per cent of loans slip into default after as little as 90 days (see Figure 6.5). The repayment rate of micro entrepreneurs stands at more than 99 per cent. The following explains how many defaults may be “mended.”

FIGURE 6.5 Portfolio at Risk (PAR) of MFIs

Data Source: MIX (2016)

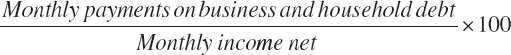

Over‐indebtedness has become increasingly rare on account of credit bureaus, and MFIs are continuously monitoring their clients' situation to be able to react swiftly to any signs of trouble. One of the parameters, and an early warning system that MFIs employ, is the so‐called over‐indebtedness index, explained as follows (see Figure 6.6):

FIGURE 6.6 Over‐Indebtedness Index and Over‐Indebtedness Factor

Data Source: Schicks (2011); Liv (2013)

In practice, a factor below 76 per cent indicates that the borrower is solvent and therefore will be able to redeem his or her loan. A factor between 76 and 100 per cent suggests that the borrower's repayments could be threatened. MFIs therefore often react when the index approaches the 76 per cent threshold. A factor of over 100 would imply over‐indebtedness.

What are the triggers of over‐indebtedness? The number one reason for over‐indebtedness is repeated borrowing, followed by a lack of cash flows from a client's business activity, and their lack of financial knowledge or poor education.17

A survey of borrower behavior in Cambodia has revealed that a debt resulting from multiple loans with different MFIs severely decreases a borrower's likelihood of repayment.18 An increase in loans that are taken out at the same time substantially raises repayment difficulties. Borrowers with more than four outstanding loans show a surge in repayment difficulties compared to those who have only one to three outstanding loans.

Another reason for over‐indebtedness is that the proceeds from a micro entrepreneur's business are too low to cover the debts including interest. To avoid over‐indebtedness of this nature, and to ensure that borrowers will adhere to their duties even if the market changes, it is vital to review and sculpt a particular business idea, as well as the cash flows generated by a potential project.

Borrowers' lack of financial knowledge prevents them from managing their finances sustainably and thereby repaying their debts. As a result, borrowers with an insufficient knowledge of the financial consequences are more prone to take multiple loans with different MFIs. MFIs in turn have recognized this and are now offering their clients training and upgrade courses that should make them more financially versatile. At the same time, credit bureaus put a halt to excessive and multiple borrowing.

Education in particular correlates positively with the rate of repayment, not least because educated borrowers more easily understand the relationship between finances and business.

Economic factors such as food inflation, diseases in plants, crop failure, as well as death and theft of livestock can lead to shocks in borrowers. This, however, need not necessarily be linked to over‐indebtedness, as different borrowers follow different courses of action. Borrowers who invest in livestock and grain cultivation are more likely to meet their financial responsibilities than less diversified borrowers.

6.5 DEFAULT PREVENTION AND RESTRUCTURING

In the following, Peru will serve as an example for the prevention measures taken by regulators and MFIs to avoid possible over‐indebtedness on the one hand and illustrate the procedures of MFIs in cases of default on the other.

Market Overview

Peru boasts a highly developed and well‐regulated financial market serving more than 4.1 million micro entrepreneurs. A wide range of MFIs, small NGOs and commercial banks characterize the market. Consumer protection is enforced by SBS and INDECOPI,19 the two regulators for financial service providers. SBS operates a central financial database that collects customer data concerning the debt charges of financial institutions on a monthly basis. This data is shared with a credit bureau that in turn supplies information to regulated and non‐regulated MFIs. These collective efforts aim to combat over‐indebtedness in microfinance enterprises by thwarting attempts to take out multiple loans with various MFIs at the same time. Borrowers with default issues in particular are targeted to keep them from taking out further loans to cover the costs of previous ones, as this strategy usually leads to a spiral of debt.20

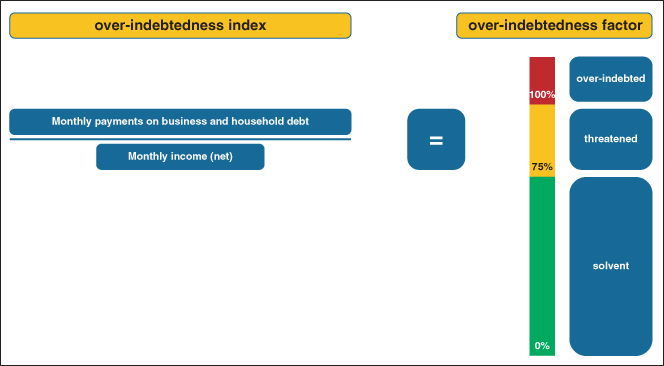

Standard Measures in Case of Loan Default

If a borrower slips into default, an MFI will typically react after 7 to 15 days. It is common practice to contact the borrower by telephone, SMS or in an email as a first step. As a rule, the loan officer is in charge of the collection of outstanding payments for up to 30 days upon detection of default. Loan officers may sanction defaulted borrowers as they deem appropriate within a range of possible courses of action. Many MFIs have considerable leeway when it comes to collecting debts and they take different factors into consideration that may have led to a defaulted installment. In rural areas, for instance, borrowers may have experienced difficulties transporting their goods. As a result of their late arrival in the market, they suffer financial losses. Beyond that, there are manifold reasons for short‐term default that do not suggest that a micro entrepreneur is unable or unwilling to repay a loan. In addition to this, a loan officer's visit to a client's home in order to assess their loan situation is costly and time‐consuming, which explains why MFIs reluctantly resort to such measures straight away. Ultimately, the strong presence of credit bureaus is largely responsible for MFIs' delay in reaction to defaulted installments. Micro entrepreneurs are fully aware that defaulted payments lead to a negative credit rating and thus severely compromise their chances of any future loans.

If a late payment nevertheless is prolonged, after 30 days, the majority of MFIs will dispatch a loan officer to the client's home to assess the situation and attempt to address the problem on hand. In most cases, a chat will suffice for a mutual agreement. If not, and upon repeated default, the case will be transferred to a special internal department that is exclusively in charge of defaults. After a 60‐day period of default, loans are often restructured and there will be a so‐called haircut, or a reduction in interest rate. Micro entrepreneurs are closely involved in the restructuring process, which additionally strengthens the lender–borrower relationship. As a matter of fact, the vast majority of borrowers will adhere to the new terms and stay faithful clients of a particular MFI. Some MFIs, moreover, provide defaulted borrowers with special services such as comprehensive credit counseling. Such services – and the MFIs providing them – do recognize that many loan complications are a direct result of a borrower's domestic situation. If no solution can be found, defaulted installments are written off after 120 days, albeit the debts remain registered with the credit bureau – and in many cases MFIs will continue to attempt to collect them over a long period of time. Figure 6.7 is an overview of the measures taken by MFIs upon detection of default.21

FIGURE 6.7 Measures upon Detection of Default

Data Source: Solli, Galindo, Rizzi, Rhyne and van de Walle (2015)

It can be safely concluded that MFIs and their loan officers are more than anxious to avoid their clients' over‐indebtedness, and for this reason supply a comprehensive package of measures that aims to find the best possible solution for both parties in the event of default. The role of a loan officer in the lending process is given further attention in the following.

6.6 OCCUPATION: LOAN OFFICER

The loan officer of an MFI embraces the entire process when micro entrepreneurs are granted loans. Business ideas, current business activities, as well as creditworthiness of potential clients are all assessed and rated.

Profile of a Loan Officer

Loan officers carry considerable responsibility and are therefore screened and scrutinized during their recruitment. They must have a well‐balanced personal and skills profile. Loan officers must also be respected and responsible members of society, and display a particularly strong intrinsic motivation and act as role models at all times. Formally, their expected behavior is recorded in a code of conduct. Any offences will be sanctioned rapidly and rigorously.

Loan officers' skills typically involve technical and specialized knowledge of microfinance, but beyond that they are required to have a state‐of‐the‐art knowledge of the entire range of legal and regulatory requirements and adamantly keep up to date. A profound knowledge of human nature and strong local ties are most beneficial too. In the cultural regions relevant to microfinance, personal contact is imperative in business relationships. Clients must therefore be able to trust their loan officer wholeheartedly for a solid and long‐term relationship.22

Process

Figure 6.8 displays the screening and reviewing procedure of potential borrowers. In a first step of the loan granting procedure, a loan officer will advise their client: both transactions and mission of a chosen MFI are introduced and the MFI's credit policy is explained. Should a micro entrepreneur decide to apply for a loan, his or her application is registered with the MFI. The loan officer decides whether the MFI will support a potential client's enterprise based on this preliminary application form. In the case of a decision in favor of the applicant, the loan officer assesses the client's business plan and financial statements with respect to the entrepreneurial and financial admission requirements. The assessment of a client's application takes seven days.

FIGURE 6.8 Procedure to Assess Potential MFI Clients

A further seven days are dedicated to assessing a client's creditworthiness. After a visit on the client's premises and an ensuing conversation, the loan officer decides if the client has a high or low credit risk profile. The client's information on the application form and his or her business plan, as well as the local framework, are taken into consideration. The local framework may include the implementation of the business plan, but also the micro entrepreneur's accommodation, geographical location, his or her relationships with neighbors and support from friends and family.

If the subsequent assessment leads to a positive decision, the loan contract can be prepared. This procedure takes another seven days. As many as 20 to 25 days may therefore elapse between a first advisory meeting and the actual signing of the contract.

Appendix A shows an example of a loan application form.

6.7 PRELIMINARY CONCLUSIONS

Classic credit theory by Stiglitz and Weiss (1981) investigates credit behavior in an environment of imperfect information. Via selection by means of financial collateral or the amount of an interest rate, asymmetrical information, moral hazard and adverse selection are reduced. Credit rationing occurs when borrowers are willing to pay a higher rate than the equilibrium interest rate at which banks offer loans. The reason for this is that with higher interest rates, banks also expect higher repayment default rates and the interest does not compensate for the losses incurred.

Lending in microfinance is based on a sense of security (i.e. trust), since micro entrepreneurs are unable to bring in financial collateral when taking their first loan. Lending methodologies and socio‐economic factors are decisive elements when it comes to credit contracts.

Any appropriate lending methodology relies on a micro entrepreneur's readiness and ability to repay their debts. Group loans, mutual monitoring, a progressive loan structure and regular meetings with the MFI of choice are indispensable in securing high repayment morale.

Location and market proximity are key elements too. In addition to this, it has become evident that women carry considerably more responsibility for their families than men. These two socio‐economic factors have a positive influence on the repayment rate of micro entrepreneurs.

And yet there are occasionally cases of over‐indebtedness of micro entrepreneurs, in developing as in industrialized countries. Credit bureaus and training programs in financial and business matters counteract over‐indebtedness and lower default rates, therefore acting as a sustainable catalyst for the success of micro entrepreneurial endeavors. In general, the PAR is rather low, as only 1 to 2 per cent of all the granted loans are defaulted for longer than a period of 90 days.