CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Worldwide, almost 1 billion people have to live on less than $1.9 a day.

World Bank1

More than half of the world's population lives on an annual income of less than $2500 – the equivalent of about $7 a day. Africa, Latin America and South Asia account for the largest part of the population living below the respective national poverty line.

In the past, the limited offer of financial services has been one of the main pitfalls. There was a lack of financial infrastructure and products tailored to the needs of people and households living on a low income.

1.1 FIGHTING POVERTY

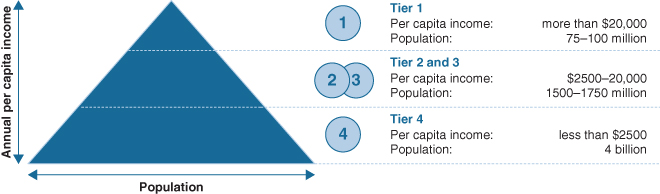

While less than 1.5 per cent of the world's population live on an annual income of over $20,000, more than half of the people around the world have to get by on less than $2500 a year (see Figure 1.1), the equivalent of no more than $7 a day. More than 2.5 billion people live on as little as $4 or less per day.2 Such living conditions are officially referred to as poverty. The World Bank uses the term “extreme poverty” in cases falling below the $1.9 a day line – almost 1 billion worldwide are constrained to a life on as little as that.3

FIGURE 1.1 Economic Pyramid

Data Source: Prahalad and Hart (2002); World Bank (2001), adjusted according to World Bank (2016)

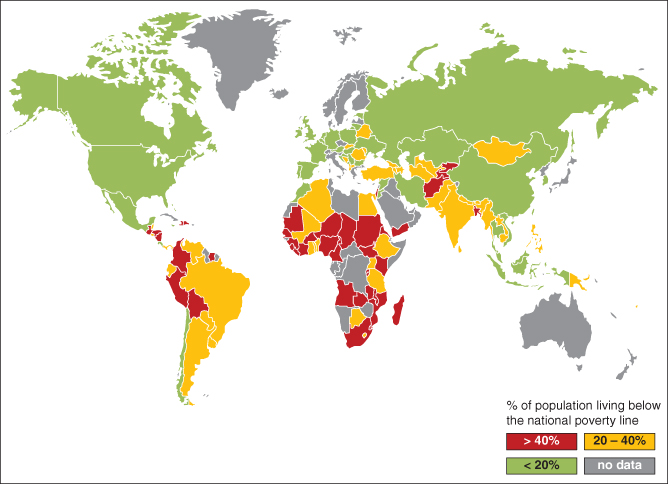

A look at the poverty levels of individual regions reveals that in many African countries more than 20 per cent of the population is living below the national poverty line. In most African countries, more than 40 per cent of people live below the national poverty line (see Figure 1.2). Latin America presents a similar situation, with Chile making a notable exception with less than 20 per cent of people living in poverty. Extreme poverty dominates in Central Asian states such as Afghanistan, Tajikistan and Kirgizstan. In South Asia and East Europe a staggering 20 to 40 per cent of the population are struggling below the national poverty line.

FIGURE 1.2 Prevalence of Poverty with Respect to Country

Data Source: CIA World Factbook (2008)

Poverty is accountable for an insufficient dietary intake, causes famines and undeniably constitutes a health threat to anyone subjected to it. The poor are prone to illnesses, have restricted access to education, and women in particular are often victims of physical and psychological abuse.

The triggers and problems of poverty are well known. In efforts galvanized by the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Development Co‐operation Directorate of the Organization for Economic Co‐operation and Development (OECD)4, and several non‐governmental organizations (NGOs), the International Community designed development goals built on this knowledge and out of this came the United Nations (UN, UNO) Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 2001. The MDGs were a set of eight goals designed to achieve and implement the targets of the United Nations Millennium Declaration by 2015 (see Figure 1.3).5

FIGURE 1.3 Millennium Development Goals

Data Source: McCann Erickson/UNDP Brazil

The first seven goals committed developing countries to employing financial means in their combat against poverty and corruption and to promote democratization and gender equality at the same time. The eighth goal obliged industrial countries to use their global economic authority in a bid to assist developing countries and achieve equality of all countries worldwide. Improving the situation of those afflicted by poverty, however, goes beyond merely devising goals, but should rather focus on effective measures. This in turn warrants an understanding of the underlying causes of poverty.

The problem is multi‐layered, and people's economic and social situation is influenced by different factors. What has, however, become increasingly evident is that access to capital and financial services is pivotal in fostering economic growth.6 And yet, individuals and households with a low income above all rarely have access to capital. Encouraging financial inclusion is therefore of the essence in the fight against poverty.

The implementation of the goals may be considered an overall success. The most important goal – the reduction of extreme poverty by half – has certainly been reached. Beyond this, the supply of drinking water has been improved, and considerable progress was made in connection with further objectives such as eradicating hunger and promoting gender equality. These are without doubt essential developmental steps.

However, albeit regarded as an overall success, the MDGs have been subject to criticism as well. Some critics maintain that their goals fell short of more general topics and focused on issues concerning developing countries exclusively, whereas industrial countries should be more willfully reminded of their commitment with respect to sustainability. Other voices argued that the partly flagging implementation of the MDGs was a result of the sustaining lack of political intent to create the necessary parameters in order to provide financing for development.7

In the wake of the criticism of the MDGs, the member states at the UN summit in Rio de Janeiro in 2012 agreed that a consistent and universal solution was indispensable in the battle against poverty. They furthermore concurred that sustainable development must no longer be regarded as a separate issue when fighting poverty, but that both goals are to be pursued simultaneously. Industrial countries for this reason should not only offer support to developing countries, but in turn commit themselves to sustainable development in their own countries at the same time.

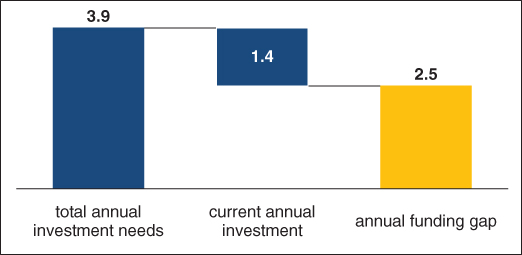

With the lapse of the MDGs at the end of 2015, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have been devised with the target date of 2030. They also promote private sector investment. Developing countries alone are faced with a staggering annual funding gap of $2.5 trillion (see Figure 1.4) with the current level of investment in SDG‐relevant sectors. Investments of the private sector are therefore indispensable, and consequently banks, pension funds, insurance companies, foundations and transnational companies should boost their investments in SDG‐relevant sectors.8

FIGURE 1.4 Annual Investment Needs (in $ trillion)

Data Source: UNCTAD (2014)

Figure 1.5 displays the 17 SDGs as defined and no longer confined to developing countries. Instead, they do apply to industrial states at the same time. The first eight goals are strongly reminiscent of the MDGs and challenge problems such as poverty, hunger, education and water supply. Environmental contemplations and action plans, justice, prosperity and food security newly join the ranks of the previous goals. It is evident that climate change is a core issue of these SDGs; 12 goals refer to sustainable development and climate change. Alarmingly, 14 of the 15 hottest years on record have in fact occurred in the twenty‐first century.9

FIGURE 1.5 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Data Source: United Nations (2014)

1.2 INVESTING IN FINANCIAL INFRASTRUCTURE

In retrospect, the limited offer of financial services almost made it impossible to access them altogether. There was a lack of both financial infrastructure and tailored products for the needs of people and households living on a low income.

Under the direction of the world's leading development banks, the financial infrastructure in development countries has experienced a remarkable surge in recent years. Together with private investors, financial institutions have been founded that efficiently serve people in developing countries and offer products that are tailored to their needs.

Microloans in particular are such tailored products. Owing to Muhammad Yunus, the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize laureate, modern microfinance has become a household name. Despite, or perhaps rather thanks to, a simple idea, its success has been truly remarkable: poor people receive a loan, fast and without collateral, which allows them to create employment to improve their livelihoods.

At present, 200 million people all over the world benefit from such microloans.10 Development banks still are substantial investors and continue to play an integral part in the development of the microfinance sector. However, the sector has now reached a grade of maturity that increasingly allows for private investors. Private people and institutional investors alike thus have the opportunity to use their investment decisions to actively support inclusion of poor demographic groups and achieve an attractive return at the same time.

1.3 CONTENT OVERVIEW

This book offers an in‐depth look at the concept and the effects of impact investing using the example of microfinance. Impact investing yields a financial as well as a social return.

Chapters 1 to 3 will introduce the reader to the topic and offer an overview of the industry, its agents and their roles. Chapters 4 to 7 in turn will focus on the different micro entrepreneurs and microfinance institutions (MFIs), followed by the principles of loan granting, the be‐all and end‐all of microfinance.

Microfinance investment differs substantially from conventional investment. Chapters 8 to 10 will elaborate on those differences and closely inspect investment and diversification possibilities for investors. These chapters will also be dedicated to the question of why microfinance investment as such – particularly, however, in a portfolio context – can yield an attractive return. Chapter 11 explores the influence of real economy and global financial economy on microfinance and its protagonists. A summary of the main arguments and discussion thereof (Chapter 12) will conclude this book.