Who Uses What on Social Media… and Why

Good Lord! who can account for the fathomless folly of the public?

2.1 Users and User Behavior

Why People Use Social Media

Social media was not an invention of the digital age—so it is no surprise that the psychological and sociological concept on which effective social media is founded—social exchange theory—also predates the Internet. Indeed, the seminal works on the subject were published by Homans in 1958 and 1961, Thibaut et al. in 1959, and Blau in 1964. Social exchange theory is built on the premise that social behavior results from an exchange process where each party seeks to maximize benefits and minimize costs. Such costs and benefits are not only intangible but differ from individual to individual. Each person weighs cost versus benefit to assess if the exchange is of benefit to them. The theory concludes that if the perceived risks outweigh the potential rewards then any potential relationship will cease. In the real world, not only can the risks and rewards be complex, but the start or end of a relationship can also be fraught with problems. Online, however, they can be more easily gained or discarded—the click of a mouse or tap of a screen being all that is required to accept or reject any social contact. For social media to be effective, however, messages must pass from more than one individual to another—there must be a network of acquaintances to pass them on to.

In his influential paper on social networking, The Strength of Weak Ties (1973), Granovetter takes this a stage further by arguing that acquaintances do not all carry equal rank. We have strong ties with family, close friends, and immediate coworkers, those being the most receptive to any contact we make. Those close friends have their own collection of strong ties, but the connection between the two clusters being only a weak tie. For any social network to be effective, participants are dependent on both strong and weak relationships (ties) in order for their message to get maximum exposure. Offline, this effectiveness is problematic, being reliant on acquaintances (weak ties) relaying a message to their close friends (strong ties) to continue the transmission of a message. In an online environment, however, with the simple click of a mouse, tap of a screen, or voice command, any message can be instantaneously sent to both friends and acquaintances—strong and weak ties. Furthermore, with similar digital ease, those people can forward the message to their friends and acquaintances (and so on and so on). Geography and time zones present no barrier. Compare that with the Romans writing a message on a wall.

Frenzen and Nakamoto (1993) took the model a stage further by investigating the impact of any benefits (the value of information) and cost (moral hazard) in forwarding the message. In their study, news of a discounted price offer was included in a message—so introducing a business-related element to what was previously a noncommercial concept. In their study, the value—benefit—was the discount rate and the moral aspect—cost—was availability of stock. Any observer of human behavior will not be surprised to learn that as the discount rate rose and the subsequent availability of stock decreased, respondents were far less likely to pass on the message to a wider circle of contacts (their weak links). This was because they perceived that if more people (the weak links) knew the information, then their close friends (strong links) were less likely to benefit. Although their research focused on the social aspect of social media, the findings of Cebrian et al. (2017) support the notion that social media isn’t totally altruistic, with their team creating a viral campaign that outperformed those of competitors by offering an incentive scheme that motivated people to recruit their social media friends. Although centered on societal issues, Frenzen and Nakamoto’s study is also relevant to marketers in their goal of having consumers forward marketing messages to their friends and acquaintances. In Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations (1962), for the diffusion to be effective there is a dependence on innovators to pass on their opinion of a product to early adopters, them on to early majority, and so on. At each stage the message-passer will seek to gain kudos from their knowledge (the benefit), but the innovator will want the message to be restricted to close contacts, their status diminishing if the message leaps from innovator to laggard too quickly. Granovetter’s Weak Ties concept was the basis for a pictorial representation of how relationships with, or connections to, other people spread out from an individual. Called the Social Graph the model became fashionable in 2007 when Facebook founder, Mark Zuckerberg, used the phrase to describe his new company’s platform. The graph (see Figure 2.1) shows how ties get weaker as they spread from the center. Depending on the strength of their connection these can be described as direct and indirect relationships.

Facebook extended this when in 2010 it launched Open Graph—a kind of global chart that had the goal of mapping everybody and how they’re related. Although this was of significant interest in social science, it was Facebook’s commercial application that piqued the interest of marketers. Open Graph facilitated Facebook in gaining insights into its members and users that could help it sell more advertising—essential for a company with no other source of income. The paradigm was that if someone liked a comment made on a Facebook page about—for example—a particular rock band, then it would be a reasonable assumption that the liker would be a potential buyer of tickets or memorabilia for that band or other artists with a similar style of music—and so a target for adverts featuring such products.

Figure 2.1 The social graph

An individual’s participation in social media is driven by different psychological motivation, which may include any of the following reasons:

• People simply like to socialize—it is a natural state of affairs for humankind.

• Social media can massage the ego, providing personal validation sought by some people.

• People seek to expand their network of relationships.

• To achieve status within a community.

• Self-expression—on social media the world can read, see, or hear your views.

• To better themselves by seeking knowledge, education, or work.

• To seek out reviews for products from real people rather than marketers.

• People can use social media as an avenue for altruistic acts that benefit the community.

Participation in social media does not require a contribution to it, however. Research in 2006 by Jakob Nielsen found that in reality very few users actually contribute, suggesting participation more or less follows the rule that:

• 90 percent are lurkers—that is; they read or observe, but don’t contribute.

• 9 percent contribute occasionally.

• 1 percent participate a lot and account for most contributions.

Nielsen’s findings go on to point out that blogs have an even worse level of participation than his 90-9-1 rule—for them the contribution ratio is more like 95-4.9-0.1. Involvement in Wiki sites is lower again. Wikipedia’s most active thousand contributors—0.003 percent of its users—contribute around two-thirds of the site’s edits. Nielsen maintains that the figures have changed little since then, with empirical evidence and a lack of contradictory research suggesting he is correct. Although lurking on some sites can be explained as being entertained (e.g., watching videos posted by others), information search (e.g., reading reviews), or voyeurism (e.g., watching or reading about the actions of others), much of it is explained by a phenomenon known as social validation, or—more commonly in the digital environment—social proof. With foundations in societal behavior (etiquette at a formal occasion, or simply following the herd, for example), social proof is the emotional experience people face when unaware of the socially acceptable behavior in a given circumstance or event. This leads them to seek guidance and/or validation from those they consider to be peers. Although a societal issue within social media, the concept is significant for those seeking to practice marketing in social media in that it explains—among other things—the wary customer seeking the reviews or opinions of others (on social media) before making a buying decision. This commercialization of social proof was led by Robert Cialdini who, in his 1983 book Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion lists social proof (people will do things that they see other people are doing) as one of the six weapons of influence that can be used in persuasive marketing. Potential customers seeking the views of peers prior before committing to a purchase have given rise to the phenomenon of people trusting someone like me rather than marketing messages. Indeed, the notion that people trust other people (more than marketers) has been advanced by Reichelt et al. (2014) who found that trustworthiness emerged as predominant in electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM), with positive impacts on both the utilitarian and the social function of eWOM. Reichelt’s research included more bad news for marketers in that it determined that the person seeking the message trusted a peer with limited knowledge of the product’s attributes, uses, or applications rather than the company selling the product that might be expected to know far more about the product.

If Nielsen set the ball rolling with his description of some social media users as lurkers, others have been quick to pick up that ball and run for the end zone. Many personality types to describe users of social media have been proposed, but one that seems to hit more than it misses was developed as part of a research project by First Direct (2013). Its suggestion for the new breed of social media personas included the following:

• Ultras are fanatically obsessed with the likes of Facebook and Twitter, they use smartphone apps to check their social media pages dozens of times a day—even when they should be doing something else, such as work.

• Deniers claim social media doesn’t control their lives, but the reality is it does.

• Dippers access their pages infrequently, often going days—or even weeks—without engaging.

• Virgins sign up to social networks but struggle initially to get to grips with the workings of the various platforms, but they may go on to become ultras.

• Lurkers (thank you, Mr Nielsen) are hiding in the shadows of cyberspace, they rarely participate in social media conversations, perhaps because they worry about having nothing interesting to say.

• Peacocks are easily recognized because they love to show everyone how popular they are. They compete with friends for followers or fans, or how many likes or re-tweets they get.

• Ranters are meek and mild in face-to-face conversation, but are highly opinionated online. Social media allows them to have strong opinions without worrying how others will react in face-to-face confrontations.

• Ghosts are worried about giving out personal information to strangers, so they create usernames to stay anonymous or have noticeably sparse profiles and timelines.

• Changelings go beyond being anonymous—adopting very different personalities, confident in the knowledge that no one knows their real identity.

• Quizzers like to ask questions on social media in order to start conversations and so avoid the risk of being left out.

• Informers are the first to spot interesting information, earn kudos and—importantly—more followers and fans by disseminating it.

• Approval-seekers worry about how many likes, comments, re-tweets, and so on that they get and, because they associate endorsement with popularity, constantly check their feeds and timelines.

Do you recognize yourself? Or are you not willing to recognize yourself? I will admit that the closest of these to my social media personality is that of dipper. However, with regard to building the background knowledge required to write a book on the subject, I lurk more than might be considered healthy.

Zhu and Chen (2015) take a different approach, presenting the public’s use of social media as a matrix (shown in Table 2.1) dividing the various platforms into those that address content- and profile-based against customized and broadcast messages. Note that Zhu and Chen’s matrix refers only to social use of social media and not how marketers use it for different kinds of message. We will revisit this matrix in the final chapter.

Research into how people use social media is manifold—with a concentration on its societal use. An extensive study for Childnet International (2008), for example, resulted in multiple reasons for using social media—but none could be described as having any connection with an organization, brand, or product’s social media marketing efforts (e.g., there was no mention of seeking product information, or reviews of a service). This reflects a notion that has pervaded digital marketing since social media became chic. That is: when users go to search engines (e.g., Google), e-commerce sites (e.g., Wal-Mart), and third-party retail platforms (e.g., eBay) they are in buyer mode—making them receptive to marketing messages. But they visit social media sites in social mode, making them unreceptive to marketing messages.

Table 2.1 The social media matrix (Zhu and Chen 2015)

|

Customized message |

Broadcast message |

Profile-based |

Relationship Allows users to connect, reconnect, communicate, and build relationships (e.g., Facebook). |

Self-media Allows users to broadcast their updates and others to follow (e.g., Twitter). |

Content-based |

Collaboration Allows users to collaboratively find answers, advice, and help (e.g., Reddit). |

Creative outlet Allows users to share their interest, creativity, and hobbies with each other (e.g., Pinterest). |

I’ll end this section with some academic research from the field of psychology—in particular, narcissism. A paper by McCain and Campbell (2016) revealed that grandiose narcissism, the more extroverted, callous form (of narcissism), positively related to time spent on social media, the frequency of updates, number of friends/followers, and the frequency of posting selfies. Now why does that not surprise me?

2.2 What Platforms Are Out There?

Here’s my list of social media sites circa summer 2017:

About.me, Academia.edu, Advogato, Airtime, Amazon Spark, aNobii, AsianAve, Ask.fm, Athlinks, Audimated, Badoo, Baidu Tieba, Bebo, Biip.no, BlackPlanet, Busuu, BuzzNet, Cabana, CafeMom, Care2, CaringBridge, Cellufun, Classmates, Cloob, ClusterFunk, CouchSurfing, CozCot, Crunchyroll, Cucumbertown, Cyworld, Dailymotion, DailyStrength, delicious, deNA, DeviantArt, Diaspora, Disaboom, Dol-2day, DontStayIn, Draugiem.lv, douban, Doximity, Dreamwidth, DXY.cn, Elftown, Elixio, English, baby!, Entropia Universe, Epernicus, Eons.com, eToro, Experience Project, Exploroo, Facebook, Facebook Workplace, Facebook Spaces, FC2, Fetlife, FilmAffinity, Filmow, FledgeWing, Flixter, Flickr, Focus.com, Fotki, Fotolog, Foursquare, FreshTeam, Friendica, Friendster, Fuelmyblog, Foursquare, Funny or die, Gaia Online, GamerDNA, Gapyear.com, Gather.com, Gays.com, Geni.com, Gentle-mint, GetGlue, GirlsAskGuys, GoodReads, Goodwizz, Google+, GREE, Grono.net, Groupon, Habbo, hi5, Hospitality Club, Hotlist, Hub Culture, Ibibo, Identi.ca, Indaba Music, Infield Chatter, Influenster, Instagram, IRC-Galleria, italki.com, Kaixin001, Kiwibox, Last.fm, Late Night Shots, LibraryThing, Lifeknot, Line, Linkagoal, LinkedIn, LinkExpats, Listography, Litsy, LiveJournal, Livemocha, Mastodon, MeetMe, Meettheboss, Meetup, MeWe, MyMFB, Mixi, MocoSpace, Mottle, Mouth-Shut.com, MyHeritage, MyLife, My Opera, Myspace, Nasza-klasa.pl, Netlog, Nexopia, Nextdoor, Ning, Odnoklassniki, OUTeverywhere, PatientsLikeMe, Partyflock, Pingsta, Pinterest, Playlist.com, Plurk, Poolwo, Qzone, Quirky, Raptr, Ravelry, Reddit, Renren, ReverbNation.com, Sina Weibo, Skype, Skyrock, Snapchat, Snapfish, Socl, Sonico, SoundCloud, Spot.IM, Spotify, Stage 32, Streetlife, StudiVZ, StumbleUpon, Tagged, Talkbiznow, Taltopia, Taringa, Telegram, TermWiki, TencentQQ, The-dots, The-Sphere, Threadless, Tout, TravBuddy.com, Travellerspoint, tribe.net, Trombi.com, Tsu, Tuenti, Tumblr, Twitter, Uplike, Vampirefreaks, Viadeo, Viber, VK, Vox, Wattpad.wayn, Wechat, WeeWorld, We Heart It, weRead, Whatsapp, Who’s In, WriteAPrisoner.com, Xanga, XING, Yammer, Yelp, Yookos, YouTube, YouTube Community, YY.com, Zoo.gr, Zooppa, and Zynga.

As well as overworking Microsoft Word’s spell-check facility on my PC, this list is reasonably comprehensive. However, it does not include all those millions of forums set up for like-minded folk to postulate, argue, seek advice, and generally converse with those who have similar interests. It is also the case that on social media—as in life—nothing lasts forever. As I write this, Twitter has all but pulled the plug on Vine, a darling of social only a couple of years before for which Twitter paid a reported $30 million for it in October 2013 and one of the original social media sites, Delicious (whose domain name—del.icio.us—was perhaps the best ever example of the use of a suffix and second level name), seems to be destined for an early grave. Others that have passed on to that social media cloud in the sky include:

• Friendster, launched 2002. Perhaps the first social networking site, even if we didn’t recognize it as such at the time, it lived on as a gaming network before closing down completely (although a notice on Friendster.com says it is “taking a break”). I wonder what might it have become of it had the owners not turned down an offer from fellow new start-up Google?

• Myspace, launched 2003. The $580m News Corporation paid for it in 2005 seemed to be a bargain as within 12 months it became the most popular social network. However, Facebook came of age and proved too appealing to Myspacers and by 2008 it was in decline. It was sold in the summer of 2011 for $35m. It does, however, live on—but is a shadow of its former self.

• Friends Reunited, launched 2000. A social networking site in the UK before we knew that there was such a thing as a social networking site. This really was the introduction to the Internet for a lot of people in the UK and was commonly used in traditional media as an example of what the new online media was bringing to the world. It was purchased by TV company ITV for £175m in 2005—and sold four years later for £25m. Ouch.

• Bebo, launched 2005. The UK’s most popular social network in 2007, Bebo was acquired by AOL for $850m in 2008—only to sell it for less than $10m in 2010. Double ouch.

Note to self: if you write another book on the subject in 2027 check the list at the start of this section to see how many still exist.

We should also not forget that many new platforms are yet to make a profit. Perhaps that is why—at the time of writing—Twitter is still scratching around trying to find a buyer? Or perhaps not. When Snapchat went public in February 2017 its impressive stocks went up 44 percent on their first day of trading and valuing the company at $28bn. Not bad for a company that has a record of losing money every year of its existence.

2.3 Who Uses Which Platforms?

Previous experience has taught me that if I include here a whole host of statistics drawn from numerous sources on such issues as: how many people use which social media platforms, how often they used them and how long they stayed on them per visit they will have passed their sell-by date before the book reached the shelves (real or virtual). Add in the fact that much of the research is conducted and published by organizations with a vested interest and you have a valid reason for not including any statistics at all. To have none, however, would be remiss so I’ve included a select few, starting with the excellent Pew Research Center Social Media Update (Greenwood et al. 2016) which comes out at the end of each year—so I should get 12 months out of this data. Here are some of the more notable statistics:

• 79 percent of Internet users (68 percent of all U.S. adults) use Facebook.

• 32 percent of Internet users (28 percent of all U.S. adults) use Instagram.

• 24 percent of Internet users (21 percent of all U.S. adults) use Twitter.

• 29 percent of Internet users (25 percent of all U.S. adults) use LinkedIn.

• 31 percent of Internet users (26 percent of all U.S. adults) use Pinterest.

As might be expected, for all of the five platforms, the usage by 18- to 29-year-olds exceeds the average, with usage dropping as the age groups move up to 30 to 49, and through to 50 to 64 to 65+. Table 2.2 shows the percentage of users for each social media platform who use other platforms.

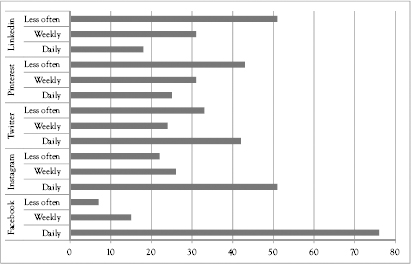

Facebook not only tops the users’ charts, but also that for the frequency of use, as is shown in Figure 2.2.

However, before digital marketers start moving their entire budgets to social media in general and Facebook in particular, in its 32nd semiannual Taking Stock With Teens research survey that questions 10,000 teens across 46 U.S. states, PiperJaffray (2016) found that teenagers (average age 16) have fallen out of love with Facebook. That research found that when it comes to their favorite social media platforms the rankings are: Snap-chat top with 35 percent, Instagram second with 24 percent, and trailing home in joint last place come Twitter and Facebook with 13 percent. If those preferences hold true as these youngsters grow older, Pew’s charts are going to look mightily different in coming years. Marketers take note.

Figure 2.2 The frequency of use on social media platforms

Source: Pew Research Center (2016).

Table 2.2 Using multiple platforms

|

Use Twitter |

Use Instagram |

Use Pinterest |

Use LinkedIn |

Use Facebook |

% of Twitter users who ... |

|

65 |

48 |

54 |

93 |

% of Instagram users who ... |

49 |

|

54 |

48 |

95 |

% of Pinterest users who ... |

38 |

57 |

|

41 |

92 |

% of LinkedIn users who ... |

45 |

53 |

43 |

|

89 |

% of Facebook users who ... |

29 |

39 |

36 |

33 |

|

Source: Pew Research Center (2016).

More research from Pew Research Center—this time their Global Attitudes Survey released in April 2017—has some rather surprising results (see Figure 2.3). The surprise is just how limited the use of both the Internet and social media is in some countries. Research—and our focus—tends to be on the United States and Northern Europe, but Japan, for example, has 28 percent of its population not using the Internet and in Germany only 37 percent use social media.

Some more numbers that social media marketers need to analyze come from respected commentators, eMarketer (eMarketer.com) who suggest that Facebook reaches around 9 in 10 social network users. That’s a great headline statistic, but further down the page comes a qualification; “on at least a monthly basis.” This actually fits with Facebook’s own interpretation of users. June 2017 saw the social networking Goliath reach the milestone of two billion users. That is, two billion monthly users. Of course, there are Facebook addicts out there who will visit several times a day, but I wonder how many of those 9 in 10 are in that once-a-month group because—let’s be realistic—“once a month” could be interpreted as “don’t really use Facebook.”

Figure 2.3 The use of the Internet and social media in various countries

Source: Pew Research Center (2016).

Research by Childnet International (2008) identified that many social media users sign up to social media platforms for the sole purpose of seeing content posted by others. The example given was that of photo-sharing site Flickr, where empty accounts are used to view their friends’ or family’s permission-protected pictures. Furthermore, could it be that a significant number of users have signed up to image-related platforms (e.g., Flickr, Instagram, and Snapchat) for one-off events—photos of weddings or vacations, for example? If such users do not cancel their membership (why would they?) they remain as part of the user numbers for those platforms. Essentially, not only more proof of the 90-9-1 rule, but a reminder that platform user statistics should be treated with caution—if not skepticism—with regard to those users being genuine targets for social media marketing.

Similarly, there are millions of blogs floating around in cyberspace that have only ever been read by their authors—who last added a post many years ago. Tracking them down would be an impossible task, but that is not the case for Twitter “tweets” which are easier to track from sender to those who read them—or more accurately, don’t read them. Research from Twitter analysts Twopcharts1 (2014) supports Nielsen’s rule, the key elements of which included that:

• Less than half of the Twitter accounts (46.8 percent) have a profile image and only 23.9 percent have a description for their account profile.

• 44 percent of the existing Twitter accounts have never sent a tweet.

• 30 percent of accounts have sent between 1 and 10 tweets.

• 13 percent of accounts have sent 100 or more tweets in their history.

• Around 11 percent of the accounts created in 2012 are tweeting a little over a year later.

It is perhaps noteworthy that Twitter didn’t comment on Twopcharts’ report—read into that what you will. I’m far from being proficient at math, but the 90-9-1 rule doesn’t look to be too far out in these statistics.

Simply by comparing data from multiple sources, Tim Peterson (Third Door Media’s social media reporter) has also shed some light on the who might read what is posted conundrum, this time regarding Instagram. In an article on Marketingland.com,2 he deduced that only around two-thirds of Instagram’s daily audience swipe past the Stories (a feature that lets users post photos and videos that vanish after 24 hours) that sit conspicuously on top of the platform’s main feeds. The flip side to this is that the one-third that do view the Stories represent around 100 million, so maybe they’re not too upset. A postscript to these numbers is that Instagram is owned by Facebook, who—as I write—is facing severe criticism from advertisers and the attention of the Media Ratings Council (MRC) amid speculation that the social media giant’s own reporting cannot be trusted following a series of mistakes in the validation of its own metrics.

I do have a couple of personal experiences of the Twitter sent versus read issue. The first dates back to the back end of 2009 when I set up my first Twitter account. It immediately gathered followers—far beyond my expectations—but as I say in my online musing of the story3:

Sadly, self-congratulation soon turned to disappointment as new followers dropped me just as quickly.

A quick check revealed a few genuine followers have stayed with me over the six months I have twittered (around 20—and six are ex-students). Now, I do appreciate that some (all?) dropped out because they saw no value in my tweets, but (a) they knew what they were signing up for, and (b) a week and two tweets is hardly time to form a judgment before jumping ship.

So why did these folk elect to follow me? My conclusion is that they are all follower whores who are simply trying to achieve high follower numbers. Further analysis of my Twitter account shows that the vast majority of my joiners both follow, and are followed by, significant numbers. They also have little or no interest in Internet marketing. The key to the issue is in the e-mail sent telling you of a new follower. It says: “You may follow [their name] as well by clicking on the follow button on their profile.” Yes, I’m supposed to reward new followers by following them. I don’t—so I’m quickly dropped.

And, of course, this is the Internet—where there is software for every occasion. In reality, these folk don’t actually visit my Twitter page to sign up—they send Twitter followbots to automatically follow users (in my case, it seems randomly, though they can be targeted to demographic data or use of keywords) in the hope that users will follow them in return.

Need some numbers? Of my 65 short-term twitterers, the average number of twits they were following was 5,852 and were followed by 6,043. Some bloke in New England topped the list with 43,980 and 44,443 respectively. If each followed member sent him only one tweet a week that is 261 every hour. Are you telling me that this guy has time to read all the tweets that land in his account?

Within a couple of months I stopped using that Twitter page but did not close the account—posting on it the message: “I’m giving up on this Twitter malarkey,” and I’ve added nothing since then. That did not, however, stop nearly 300 users choosing to follow a dead twitterer—enough to prove my point about follow-bots and Twitter whores?

The second example is more recent, and comes from a source I use to keep me up-to-date with what is actually happening out there in the digital marketing world, clickz.com. One article from July 2016 gave a list of “100+ marketing leaders you should follow on Twitter.4” Now, I have no issue with the list, or even the concept of offering a list of people to follow—not everyone has been around as long as me, we all need help when getting started. Neither do I have any problem with the fact that I’m not on the list (another smiley face). My point is this: I have a professional interest in all of the subjects listed and so might decide to follow them all. If each of these leaders tweeted just once a week, that equates to around 14 tweets a day—with each tweet probably linked to an article to look at. I’ll let you do the math for the numbers if they tweeted more often, say once a day. So, (a) when am I supposed to find the time to read all of these things, and (b) what about any other sources I already follow? Plus I’m in a job where part of that job is to keep myself updated on the subject—what if you are busy digitally marketing all day?’ Nuff said?

And these issues aren’t limited to Twitter. Because—frankly—life is too short, I have not kept track of the numbers, but hardly a day goes by that I do not receive a “so-and-so wants to join your network” e-mail from LinkedIn. They may not be robots, but if I do not know so-and-so in real life I simply reject their request. Again, I am assuming that a reciprocal request is expected so that the requester can build his or her own LinkedIn profile.

If you want to take a look at who follows whom on Facebook and Twitter, spend a few minutes on Fanpage.com.

Beyond the Pew Research Center findings is a plethora of un-referenced commentators from recent years that I think is worth your consideration. I should add that my own, very much ad-hoc and un-scientific research supports these observations.5

• Plenty of folk use social networking sites, but only around a third of those rate social media as being important to them.

• Adults who are currently a member of more than one social networking site are overloaded and/or overwhelmed with multiple social accounts and half have either taken or are considered taking a vacation from one or more social networks.

• While women are highly active and influential on social media, they are also more likely to decrease or completely stop usage of at least one social network.

• People abandoning social media cite four main reasons for quitting: privacy concerns lead the way at around 50 percent, general dissatisfaction and negative aspects of online friends at around 15 percent each are followed by 6 percent fearing that they may become addicted.

• People are more likely to share images than textual content.

Do you recognize yourself in any of these?

2.4 Why People Follow Social Media Sites of Organizations, Brands, or Products

Research into this subject abound; I have chosen to include a representative sample here. The first is from SUMO Heavy Industries (2016), which revealed some interesting information on why users are on social media (see Table 2.3).

Note how small a role finding specific information on products and services has in the use of social media. Furthermore, the same research found that, when asked about what influences consumers about a brand and its products, 56 percent said “family members” and “friends” posts. Add to that statistics that 62 percent have shared information about products and offers on social media, and it becomes a reasonable conclusion that when users are looking for product information they are looking on the pages of friends and family as much—if not more—than brands’ pages. In addition to this rather gloomy news for social media marketers, the same research also found that advertisements and sponsored posts influence less than 16 percent of social media users. Based on these numbers some might question the use of the medium at all as an effective marketing tool. Or might they be questioning just how the Emperor looks in his new clothes?

Table 2.3 Why users are on social media

Reasons |

Younger users |

Older users |

Friends and family |

87% |

77% |

Pass time |

72% |

42% |

Stay informed on news |

65% |

41% |

Entertainment |

57% |

28% |

Share personal information and content |

52% |

33% |

Learn about people |

38% |

21% |

Find specific information on products and services |

28% |

22% |

Meet new people |

24% |

6% |

Source: SUMO Heavy Industries (2016).

Table 2.4 Why consumers follow brands on social media

|

YouTube |

||||

Keep up with activities |

52% |

57% |

35% |

41% |

41% |

Learn about product/service |

56% |

47% |

56% |

61% |

39% |

Sweepstakes/promotions |

48% |

36% |

28% |

20% |

23% |

Provide helpful feedback |

32% |

27% |

22% |

23% |

22% |

Join community of brand fans |

27% |

26% |

25% |

19% |

19% |

To complain about product/service |

18% |

19% |

12% |

9% |

15% |

Source: Technorati Media (2013).

Technorati Media6 (2013) concentrated on five leading social media platforms; Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Pinterest, and Instagram. The key findings are shown in Table 2.4.

Marketers should be aware of these motives so that expectations are met. Many are self-evident and—as we will discover in later chapters—pertinent to whatever the organization does, what industry it is in, what the brand represents, or what the product or service is. Nevertheless, there are issues for marketers, not least that joining a community of brand fans sits so low down the list. Shouldn’t this be what social media is all about? One thing that—in theory—social media is not about is promotions for the brand. That is: advertising. To use a social media presence merely to host promotions does not equate to the ethos of social media marketing … but that, it would seem, is the reason many people follow brands.

Social media software suppliers, Sprout Social, provide some more up-to-date statistics in their Sprout Social Index (2016). Their research included: the actions that make people follow a brand on social media (see Figure 2.4), annoying actions brands take on social media (see Figure 2.5), and actions that make people un-follow a brand on social media (see Figure 2.6). Note the strong correlation between what annoys people and what incites them to un-follow a brand.

Figure 2.4 Actions that make people follow a brand on social media

Figure 2.5 Annoying actions brands take on social media

Figure 2.6 Actions that make people un-follow a brand on social media

Although it offers a more comprehensive range of reasons for respondents to choose from in expressing why they might follow a brand on social media, these results are strikingly similar to those of Technorati Media in that there seems to be a preponderance of folk joining to enhance their bank balance than truly social purposes. That around half seek some kind of entertainment is interesting—as is the power of peers. And what about the 42 percent who joined up for an incentive? I’m going to call that buying friends and leave it to you to decide just how loyal they are going to be to a brand.

As with the Technorati findings, there is a certain irony that so many people are annoyed by the frequency of promotions and choose to unfollow a brand because of it and yet 58.8 percent joined for promotions in the first place. That so many followers decide that the jargon/slang doesn’t fit the brand, the content has no personality or it is trying to be funny and failing suggests the brand has got its voice wrong, something covered in more detail in Chapter 5 (Section 5.2). Indeed, all of the reasons listed suggest that the brand simply does not get social media—which is a subject that presides over the book’s contents from the next chapter through to the last.

Sprout Social’s research also found that 70 percent of people have un-followed a brand because they were embarrassed that their friends might see they were following it. Compelling evidence perhaps that: (a) social media is fickle, it follows trends—and drops them just as quickly, and (b) peer pressure plays a major role in social media, which suggests a certain lack of self-confidence in users—which is relevant to marketers. And rather sad for humanity.

Furthermore, if we combine the data from SUMO Heavy Industries with that from Technorati Media and Sprout Social we have a reasonable conclusion that if only around 25 percent of users go on social media to find out about a product or service (and they may well go to friends’ or family’s pages for that information) that doesn’t leave a significant proportion of all users who are actually engaging in the activities described in the findings of Technorati Media and Sprout Social. The roundup of research data on the subject gets no better for marketers if that of Kumar et al. (2016) is accurate. They calculated that the percentage of a customer base that participates in a firm’s social media sites ranges from 1.00 percent to 7.35 percent, with an average of 3.7 percent. This group’s research combined their primary data with other secondary data to arrive at these figures, so there is no reason to cast doubt on them. But even if they were 100 percent out and the real figure is around 7 percent, that’s not really very many of the brands customers that are engaging with the organization on social media. A more pessimistic person might actually stop reading this book at this point as they consider that these numbers suggest any social media marketing would not give a reasonable return on any investment. For those glass-half-full people, stay with us, there is better news. Later in the book I raise the argument that some organizations, brands, or products are culturally better suited for social media marketing. One such brand is Starbucks, and its 36,549,3207 Facebook followers must represent more than 3.7 percent of its customer base.

It is my contention that the majority who choose to follow an organization, brand, or product do so because they are already a satisfied customer. In terms of being a customer in its most literal definition—by which I mean people purchase a product—Starbucks would be an excellent example. Why would anyone like the ubiquitous coffee provider if they hadn’t sampled the product? Research from Brodie et al. (2013) finds in favor of my contention, arguing that customers who engage with brand communities online feel more connected to their brands, trust their preferred brands more, are more committed to their chosen brands, have higher brand satisfaction, and are more brand loyal. More recently, Sprout Social (2017) found that 62 percent of people said they are likely or somewhat likely to purchase a product from a brand they follow on social media. Bagozzi and Dholakia (2006) also found that consumers who become fans of these brand fan pages tend to be loyal and committed to the company, and are more open to receiving information about the brand. My contention is that this is precisely why they are fans.

Further evidence of this comes from what I feel is the best academic journal because it isn’t too academic—the Harvard Business Review. John et al. (2017) challenged the concept that people who liked a Facebook page routinely spent more with that brand by questioning cause and consequence, investigating the possibility that “those who already have positive feelings toward a brand are more likely to follow it in the first place, and that’s why they spend more than non-followers.” Although they identified that supporting endorsements with branded content can have significant results, “the mere act of endorsing a brand does not affect a customer’s behavior or lead to increased purchasing, nor does it spur purchasing by friends.”

In effect, we are looking at whether or not people are predisposed to have a relationship with an organization, brand, or product. This is something I have questioned with regard to the concept of relationship marketing—of which social media marketing is at least a relative, but more likely an element. Here’s the thing: people do not necessarily want a relationship with an organization, brand, or product—why would they? Take a look at the aforementioned Fanpagelist site to see how poorly brands fare in the follow and like leagues—and don’t forget the percentage of folk who like firms purely for the discount coupons. Research by Dixon and Ponomareff supports this premise—the title of their 2010 Harvard Business Review article making their case. In “Why Your Customers Don’t Want to Talk to You” the authors make the point that customers these days demonstrate a huge appetite for self-service—the result of their preference not to interact with the sellers. So if a customer would rather use an ATM than a bank teller, why would that same customer want a relationship with that bank? Not for the only time in this book I put forward the assertion that if it is the right product in the right place at the right time, then most—all?—customers will not only buy a product but make repeat purchases. Interestingly, the research by SUMO Heavy Industries in 2016 found that if customers loved their purchase, 83 percent would share it on Facebook. By definition, a relationship is two-sided with both parties having to perceive an advantage to the union. Businesses want a relationship with me to sell me more goods. Well, provide me with the right product in the right place at the right price and I will continue to buy your goods. If I get the wrong choice of product; or it isn’t where I want to buy it; or its price doesn’t meet my valuation then no amount of relationship will encourage me to remain a customer. Always happy to put my own head above the digital parapet, here’s an example of my own experience with regard to relationships with brands.

This illustration is prompted by a report8 that Toyota is way ahead of its rivals when it comes to Twitter engagement, in particular its Go Fun Yourself campaign that was delivered in off- and online media. Now, although perhaps a little old, I am most definitely in the target segment for Toyota’s only sports coupe (the GT86/Scion FR-S) and it is sold as a fun car rather than a sensible, boring, go-from-A-to-B mode of transport. I have also owned Toyota cars for 20 of the last 27 years. And I have owned one particular type of Toyota sports car for 15 years and around a quarter of a million driven miles. I still have one of these now, it is 30 years old. That suggests I am a stronger supporter of Toyota than your average car owner. I also accept that—as the article accurately portrays—Toyota’s social media team is doing a fine job. But for the life of me I cannot think of a single reason why I would want a social media relationship with Toyota, that is; read dozens of Tweets that have no interest to me whatsoever. If I buy another Toyota, social media will play no role in my purchase decision or behavior. OK, I might read some owner reviews, but I will take more notice of professional reviews. Ultimately, if I like the look of the car (essential), and its interior meets my user expectations (essential—I have a back problem, the seats are a deal-breaker for me) and if I like the way it drives—that is; if the car is right for me, and if I can buy it and get it serviced locally and if the price meets what I value the car to be worth to me, then I might buy one. Of course that could be just me, and I do appreciate a less petrolhead buyer than me might be more susceptible to a social media marketing relationship, but I do wonder just how many cars Twitter engagement actually sells. Note that return on social media marketing investment is covered in Chapter 4.

Beyond my assertion of Starbucks being an example of customers supporting the brand, it would be remiss to ignore the softer characterization of being a customer of an organization, brand, or product. The data would suggest that many people do follow brands and that some do so prior to making a purchase. For example, the aforementioned Sprout Social (2017) research found that 58.9 percent of Millennials, 50.4 percent of Generation X-ers, and 55 percent of Baby Boomers have all followed a brand on social media before purchasing a product. The Sprout report does not give details of its methodology, and so I resorted to my own research to shed some light on this—after all, it does contradict my earlier assertion that there is no reason for anyone liking an organization, brand, or product if they hadn’t sampled the product?

As with most of my primary research, this was conducted in ad hoc rather than scientific fashion, but I did identify over 100 students who had liked or followed an organization, brand, or product on social media—though this was not easy; a significant number of folk have never done so. As it turned out, the answer to the conundrum came to me as I asked the respondents why they liked or followed an organization, brand, or product. Before answering they asked me to define organization, brand, or product, specifically; “are people, performers, movies and games brands?” This would be the issue I would raise with Sprout’s research—not, I hasten to add, to criticize it, just to clarify the results for my own purposes. I have to admit that when I envisage a product it is a physical product (i.e., that I use, eat, or drink) and a brand is the name on some of those products—but I’m being too simplistic. When I questioned the students (in a series of focus groups) I found that they all followed music artists, movie stars, celebrities, and comedians, the latter being very popular as postings were normally funny. In other words, following wasn’t engagement with the brand (person), it was a source of entertainment. Also popular at the time of the interviews was the movie, and stars of, La La Land (ironically the sessions sandwiched the movie’s gain and loss of the best picture award at the Oscars). Also very popular were multiplayer video games, some of which require a certain social media interaction to be fully engaged. Also popular were entertainment channels such as Netflix and Spotify as well as niche radio stations. Finally there was the one that saw me slapping my forehead in a well duh! moment: news channels. I tend to access the BBC on the radio, TV, or web. I had totally forgotten (because I don’t use them) that the BBC has a Facebook page for breaking news and Twitter accounts that will notify you of personalized news, about your sports teams, for example. For the majority of readers of this book, replace BBC with a U.S. national or local news provider of your choice. It is my opinion that examples such as these artificially boost engagement figures—they are clear exponent of Jacob Nielsen’s 90-9-1 rule and—as I will address later in the book—they are not true social media marketing. They might also give some rationalization to the research that so many people follow before purchase—liking the La La Land Facebook page before visiting a cinema to watch the movie, for example.

2 http://marketingland.com/instagram-stories-get-viewed-%E2%85%93-300-million-large-daily-audience-ignored-%E2%85%94-194197

3 See www.alancharlesworth.eu/alans-musings/what-tweeting-use-is-twitter.html

4 www.clickz.com/102-marketing-leaders-you-should-follow-on-twitter/102636/

5 It’s a personal view; but I think that informal discussions on a subject with people—often as part of wider-ranging conversations—can be far more revealing by way of research than presenting them with a series of questions in a formal questionnaire.

6 At the time Technorati’s focus was on the use of social media in marketing. Since then it has moved to being “advertising technology specialists,” which perhaps explains why 2013 was the last of a series of excellent annual reports on social media.

7 Source: Fanpagelist.com, January 8, 2017.

8 https://econsultancy.com/blog/65714-how-toyota-beats-24-other-car-brandsin-twitter-engagement