CHAPTER 15

Race, Tribe, Caste, and Class

Of the several ways in which societies get stratified, three ascriptive groups (namely, race, tribe and caste) and a category based on the criterion of achievement (class) are used as the prominent strata. Reviewing the trends in sociological research in the l980s, Neil J. Smelser noted that the ‘three words …—“race”, “ethnicity”, and “class”—enjoy wide currency both as categories in social sciences and as terms in everyday discourse. Each is employed as if it enjoys a common meaning, yet none is used with precision in either arena’ (Smelser, 1994: 280). The comment would equally apply to the word ‘caste’. Therefore, there is a need for some conceptual clarification of all these terms.

In this chapter we shall explain these key concepts as they relate to social stratification.

Race

The history of human evolution tells us that all belong to a single genus and a common species, called Homo Sapiens. This indicates the biological commonalities between all humans that distinguish them from other animals. At the same time, we note that each individual of this highly populous group (now in 2014 it is more than 7.2 billion) is physically different in a combination of physical traits. But some of the traits tend to cluster in a given population concentrated at a given geographical space—a region, or a country, or a continent. It is these clustered traits that give that population a separate identity as a race.

Analysts of race divided the entire humanity into three major clusters, namely, Caucasoid (the White), Mongoloid (the Yellow), and the Negroid (the Black). These are the three great races of Man, which have further been classified into three sub-races each (see Table 15.1 and Figure 15.1).

This classification is attempted on the basis of some observable physical traits such as colour of hair, texture of hair, quality and distribution of hair on the body, eye colour, shape of the eyelids, shape of the nose and the lips, colour of the skin, body height, type of face, and the general gait and stature. Physical anthropology has developed a set of measures1 for these indicators to classify people in racial terms.

As was said earlier in the book, race has been used as an ideological tool to emphasize the superiority of the whites over others. In fact, a science of Eugenics was developed for the purpose. This was greatly opposed by a group of anthropologists who insisted that racial superiority is a colonial construct. Ashley-Montagu went to the extent of calling it Man’s Most Dangerous Myth and wrote a book with this title in 1945 to expose the fallacy of race. UNESCO intervened in this debate right from its inception and brought out a series of pamphlets to discredit the theory of racial superiority.2

Table 15.1 Classification of Races

Caucasoid |

Mongoloid |

Negroid |

|---|---|---|

Nordic |

Asiatic |

African |

Mediterranean |

Oceanic |

Oceanic |

Alpine |

American Indian |

Negrito |

It is now generally agreed by all anthropologists that race is a biological concept and should be used in that sense. A commonly agreed definition of race is that it is ‘a major grouping of interrelated people possessing a distinctive combination of physical traits that are the result of distinctive genetic composition’ (Hoebel, 1958: 116). Four factors cause race differentials, namely, gene mutation, natural selection, genetic drift, and population mixture. Today’s world consists of people who have moved from places of their origin and mixed and intermarried with others—the process of such interactions has a long history; as a result, it is absolutely impossible to find any pure races, certainly not the early three groups of Caucasoid, Mongoloid, and Negroid. Through racial miscegenation, several hybrid combinations now prevail in the human population.

Neither can one consider language coterminous with race nor with culture. People of the same race (or any of its several sub-types caused by racial admixture) are found to speak different languages. They live in different political regimes, practice different religions, and share a variety of cultures. The fact that race figures in the discussion on stratification hints at the existence of multi-racial nations and societies. ‘Most usages of the term race refer to large populations originally or currently dominating a continental land mass or archipelago.’

We can do no better than reproduce Hoebel’s summary on the question of race and cultural capacity. He summed up thus:

- It must be acknowledged that there is the possibility of innate physiological and psychological differences between racial groups;

- However, no such differences have been scientifically isolated and unequivocally established; and

- Such differences, as indicated, are so slight in their apparent effect on human behaviour that when compared to the proven influence of culture in determining the action of men, race differences are of such relative insignificance as to be of no functional importance.

Hoebel concludes: ‘Culture, not race, is the great moulder of human society’ (1958: 147).

Figure 15.1 Major Races and Sub-races of Mankind

It is in the cultural sense that race became a variable for social discrimination, particularly during colonial times. It promoted the subjugation of Africans by the whites, who took the former as slaves and despatched them to far-off lands to do menial jobs. In a novel titled Roots, Alex Haley narrated the saga of one such man who was brought to the United States as a slave.3

The slaves constituted the bottom of the social ladder in the United States. Bought as a commodity in an auction, these people were kept in chains and denied the basic human rights. It took a long struggle to break the shackles of slavery.

Another manner in which race was used as a tool of discrimination is known as Apartheid. South Africa continued with this policy right up to the 1990s. Nelson Mandela, the fighter for the cause of the downtrodden Blacks in their own native land, was kept for years at a secluded location and tortured. But he finally won the cause and became the first president of the new Apartheid-free South Africa.

Apartheid became the official policy of the Government of South Africa in 1948, following the election of the Herenigde Nasionale Party, later renamed the Natio al Party. Under this policy, racial discrimination was institutionalized. The lives of the Africans, who made up almost 75 per cent of the population, were controlled by the unjust segregation laws from birth to the grave. They were told where to live, who to marry, and the type of education they would receive in the country of their birth. Since the founding of the African National Congress (ANC) in 1912, the Africans waged a struggle against the unjust racist laws of South Africa. Their resistance ushered in a new era on the morning of 21 March 1960, when thousands of Africans gathered peacefully in locations around the country, including in Sharpeville, where up to 20,000 marched to the police station. The police opened fire on them, killing 67 people and wounding 186 others, including 40 women and 8 children. More than 80 per cent of them were shot in the back while fleeing. During the declaration of the state of emergency in 1960, which continued intermittently for nearly 30 years, anyone could be detained without a hearing by a low-level police official for up to six months. Thousands of individuals died in custody, frequently after gruesome acts of torture. Those who were tried were sentenced to death, banished, or imprisoned for life, as was the case with the world’s most famous prisoner, Nelson Mandela.

The issue of the policies of apartheid of the Government of South Africa remained on the agenda of the United Nations for almost 50 years. After numerous efforts to urge the government of that country to abandon its policies—declared a crime against humanity—the international campaign reached a watershed in 1989. That year, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a declaration on Apartheid and its destructive consequences in Southern Africa, paving the way for the holding of the April 1994 historic and first-ever democratic elections in South Africa. © UN, 2007. Developed by DPI/News and Media Division/ Multimedia Resources Unit American anthropologist Carleton S. Coon, divided humanity into five races. In his landmark book The Races of Europe, Coon defined the Caucasian Race as encompassing the regions of Europe, Central Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, North Africa, and Northeast Africa. Coon and his work drew some charges of obsolete thinking or outright racism from a few critics, but some of the terminology he employed continues to be used even today, although the ‘-oid’ suffixes now have in part taken on negative connotations.

In the contemporary world, it is difficult to employ the criterion of pure race. Human history is replete with instances of migrations, mixing of races, and of cross-fertilization. The world divided into more than 200 nation-states does not allow classification of them in terms of race—the single race single nation formula does not work. People belonging to the same race—that is, possessing dominant characteristics of any given racial type—are to be found in several nation-states, and any single nation-state consists of people belonging to several races. It is the latter feature that has allowed the entry of the concept of stratification to be employed for discerning the internal structure of a given society. Originally, there were societies that developed a sort of symbiotic relationship between different groups; power struggle or numerical preponderance in several places later resulted in a hierarchical placement of the racial groups within a society. A tendency towards preference for endogamy made races to function as castes. In fact, the Portuguese word casta that came to be employed for the Indian jati originally meant ‘race’, ‘breed’, or ‘lineage’. That is why, Gunnar Myrdal used the metaphor of caste to describe the Black–White relationship in his famous book, Deep South, based on the empirical research conducted in the 1930s in the Southern United States. The relationship between the two groups distinguished on the basis of colour defied the use of the concept of class in that context. The purpose of this usage, according to Béteille, ‘was not so much to explore its similarity with the Indian system as to emphasize its difference from the class system in America and other Western societies’ (Béteille, 1991: 37). Caste, in this sense, is a structural and not cultural category. Smelser4 suggests that the transition from some biological notion of race to its sociological significance actually involves two distinct transitions. The first is a shift in the point of reference. Race as a sociological phenomenon is a culturally and socially constructed and sustained category … The second transition–and this leads to racism proper–occurs when another range of beliefs is invoked: for example, that particular races are superior in some way and deserve to dominate other races. With the development of racism, moreover, the issue whether race has any physical or biological basis recedes more or less completely into the background … [R]ace remains a sociologically relevant variable when it becomes the structural basis for human interaction, stratification, and domination’ (1994: 280–81).

In multiracial societies—Furnivall called them plural societies—race and class ‘merged as blacks were assigned to slavery, immigrant yellows and browns to indentured labour, and natives to agriculture’ (ibid.: 281).

Oommen introduced a new concept of racity to distinguish it from racism. In his formulation, racism refers to stigmatization and oppression; racity, in contrast refers to racial solidarity and efforts to cope with racism. Thus, racity implies the tendency of those belonging to a distinct physical type to provide others of their type with support and sustenance, particularly when confronted by an oppressive force. Some scholars also talk of aggregative racism, referring to a tendency to put a number of peoples—African, Afro-Caribbean, South Asian, etc.—into a single category of Black (of course, with different shades from dark to brown). This is a stereotyping device employed by the dominant white population in countries like the United Kingdom.

Mao Tse-tung (Mongoloid)

Patrice Lumumba (Negroid)

John F. Kennedy (Caucasoid)

Mongolian Lady

Bushman-hottentot of Africa (Such overdeveloped lower back portion of the body is called Steatopygia.)

A Caucasoid Lady from North India

In recent years, the terms ‘ethnic group’ and ‘ethnicity’ have also come in vogue. In the Indian context, for example, ethnic group has been used by some as a synonym of tribe on the one hand, and also of caste on the other. M. Blumer, in his 1986 article on ‘Race and Ethnicity’,5 defined an ethnic group as

T. K. Ommem (Courtesy: © T. K. Ommem)

… a collectivity within a larger society having real or putative common ancestry, memories of a shared past, and cultural focus on one or more symbolic elements which define the group’s identity, such as kinship, religion, shared territory, nationality, or physical appearance.

This definition is almost identical with the definition of a tribe given by S. C. Dube, which we mention later in the section on Tribe. The reference to physical appearance in the definition alludes to race and, thus, makes the distinction between race and ethnic group somewhat problematic. But an ethnic group that tends to be endogamous and localized is likely to have a greater degree of resemblance amongst its members. One can infer that people of a broader category of race are divided into several groups and these sub-groups or sub-races are to be named ethnic groups. We must also be alert to the use of the term ‘ethnic’ as an adjective for food, dresses, etc., becoming popular with the rising middle class. Here, the term refers to ‘traditional’ and exotic—almost a synonym for ‘folk’— and thus applicable not only to the tribes but also to the peasant society.

Tribe

While race is now recognized as a biological term and the physical indicators for it are well established, there seems to be no consensus regarding the concept of tribe. Pioneering anthropologists carried out their studies of primitive societies without bothering to precisely define the concept of Tribe.

This is somewhat understandable if we went back to the beginnings of the discipline of anthropology. When societies were classified into civilized and uncivilized—as savage or barbaric—the task was simpler. All uncivilized societies were preliterate, meaning thereby the absence of writing in them. That meant that the transmission of culture was through oral tradition, and the history of the society went as far back as human memory could take it. Beyond this was prehistory. Absence of history, oral transmission of society’s knowledge pool to the younger generation, elementary technology, greater dependence on nature for survival, and faith in the supernatural described their way of life. Living in small hordes, and unaware of the world outside the narrow confines of the community, the geographically and socially isolated communities defined themselves as residents of a given territory, and as belonging to a specific racial stock. Initially, students of ‘other cultures’ came to non-western societies and studied those small groups that were remotely located as ‘Little Communities’, cut off from civilizational societies and pursuing primitive economic activities in settlements that were cradle-to-the-grave arrangements.6

The popular image of the tribal was of a dark-skinned,7 semi-naked, uncouth individual who could easily be distinguished from the civilized world in terms of the ‘way of life’ led by them. When explorers went to the new world and areas other than Africa and the Pacific, and South Asia, they found the existence of tribes in the non-black populations as well. But the stereotype continued. The term ethnic group was used as a synonym for tribe. ‘Morgan’s conception of the tribe’, to quote Béteille, ‘and Durkheim’s conception of the polysegmental society were both rooted in the same evolutionary perspective. Their successors chose their examples not from India, China and the Islamic world, but from Australia, the Pacific Islands and North America where recent historical experience brought out the disjunction rather than the co-existence of tribe and civilization’ (ibid: 58).

Problems arose when countries like India were colonized. Described as an indigenous civilization, India was divided into civilized and uncivilized sections, but belonging to the non-western part of human civilization. In India, the original inhabitants were pushed into remote tribal tracts by groups that migrated from abroad at different phases of its history—as nomads and pastoralists, or as invaders who became conquerors of parts of the vast territory of India. Many such groups who came from the Middle East, Eastern Europe, and Mongolia came as adventurers or nomads and gradually got assimilated with the local populace; this involved initial confrontation, accommodation, and, finally, integration into the main stream. Historians of the nineteenth century—mostly foreign, and primarily administrators or military officers of the Raj—called all such migrating groups tribes because of their common origin and distinct identity. But they also acknowledged the process of their gradual assimilation into the Hindu fold. The multiracial society of India had a history of co-existence of tribe and civilization ‘for centuries if not millennia, and were closely implicated in each other from ancient to modern times’ (ibid.: 58).

In the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century, it was still possible to divide India into tribal, rural, and urban as if they were part of a continuum. The remote and inaccessible location and lack of contact gave a separate identity to tribals, and rural communities were sandwiched between the tribal and the urban. In today’s context, such a clear-cut division is not possible; with development taking place, many tribal areas, particularly of the Northeast, can be classified into these three categories. Tribes settled in rural communities and the emerging urban centres do not answer the stereotypical profile of the tribal. In the central parts of India, where interactions with the indigenous civilization had been the norm, their absorption within the Hindu fold (as hinted by D. D. Kosambi and N. K. Bose) has preserved their collective identities through endogamy, but converted them into castes. Any idyllic definition of the word tribe does not apply to such groups.

In the Indian context, because of a continuous culture contact with the non-tribal communities surrounding them, it becomes difficult at times to isolate the tribes. Where the representatives of these groups have settled in villages with other groups, they are treated as one of the many castes, and they interact as such in the local caste system of the village.

In India, the term tribe has been used very loosely for denoting different kinds of groups.8 It is used not only for those groups that are regarded as the original inhabitants but also for the migrant communities that came in succession from abroad to settle. British officers have freely used the term tribal for groups such as the Jats, Brahmins, and Rajputs. Many groups take recourse to such references to assert their tribal past and making a plea for their inclusion in the tribal category.

In the absence of any precise definition, S. C. Dube chose to list the characteristics that generally seem to apply to a tribe:

- Their roots in the soil date back to a very early period. If they are not original inhabitants, they are at least among the oldest inhabitants of the land. Their position, however, cannot be compared to that of the Australian aborigines, or American Indians, or native Africans. The Kols and Kirda of India had a long association with later immigrants. Mythology and history bear testimony to their encounters and intermingling.

- They live in the relative isolation of the hills and forests. This was not always so. There is evidence of their presence in the panchanad and the Gangetic Valley.

- Their sense of history is shallow for, among them, the remembered history of five to six generations tends to get merged in mythology. Some tribes have their own genealogists, with interesting anecdotes and remembered history.

- They have a low level of techno-economic development.

- In terms of their cultural ethos—language, institutions, beliefs, worldview, and customs—they stand out from the other sections of society.

- If they are not egalitarian, they are by and large at least non-hierarchic and undifferentiated. There are some exceptions: some tribes have had ruling aristocracies; others have landed gentry.9

The Constitution of Indian Republic recognizes the existence of tribes and has a schedule listing them for special treatment to facilitate their entry into the mainstream and enjoy the fruits of development. While taking this step, hailed by all as a well-intentioned policy, little attention was paid to the definition of the word tribe. Perhaps the need was not felt as tribes had been listed in the censuses since 1891. The 1931 census—regarded as the last census that had enumerated population by caste—has listed primitive tribes, the list of 1935 talks of backward tribes. Lifting these entries, the Government of India prepared the schedule in accordance with the new constitution, and included all without any exception, thus erasing a distinction between a tribe and a scheduled tribe (SC). Accordingly, the 1951 census counted 212 tribes, constituting around 6 per cent of the Indian population. Over the years, this number has burgeoned to more than 700, although the percentage of population covered by the ST category is around eight not much different from the 1951 figure, taking cognizance of population growth. This increase in the number of tribal communities, I must mention, is mainly caused by state-wise recognition of tribal groups—in other words, sub-groups of tribals have been given separate region-based identities, with the result that a group that is considered a tribe in one state might have been denied that status in another. These anomalies were pointed out by the Dheber Commission way back in 1961. For example: ‘The old state of Hyderabad (Nizam) did not recognize the Yenadis, Yerukulas, and Sugalis as Scheduled Tribes, whereas the old Andhra State recognized them as such and with abundant justification. Similar is the case of the Gaddis who are found in Himachal Pradesh and the adjoining Punjab Hills. In the Punjab, they are treated as scheduled tribes only in the scheduled areas where they do not live’. Similarly, the state of Uttar Pradesh did not recognize the Khasa of Jaunsar–Bawar and the Gonds and the Cheros of Mirzapur district as tribes. These anomalies went on rising as the years passed. For example, the Gujjars, Kinnaura, and the Lauhola are included in the schedule for Himachal Pradesh but not in Jammu and Kashmir. At a later date, the Gujjars of Jammu and Kashmir, also known as Bakarwal, and practitioners of Islam, were granted the tribal status.

It is important to note that there is no indigenous word for tribe in any of the Indian languages. In Sanskrit, there is a word Aatavika Jana (meaning Banvasi or forest dwellers), which was used to denote the agglomeration of individuals with specific territorial, kinship, and cultural patterns. Prior to the colonial period, they were also commonly referred to as a Jati—caste. But the colonial administration began calling them tribes, and differentiated them from the other groups on the basis of animism. In this category, some food gathering groups and shifting cultivators were also included, though they lived closer to the villages. In the censuses, they were first called ‘forest tribes’. In the 1931 census, they were named as primitive tribes. In 1935, the British began calling them as backward tribes.

Without questioning the nomenclature, anthropologists, both foreign and natives, took those groups as the subject matter of their study, and they were officially designated as tribes. It is interesting that in the 1931 census, which had recorded castes for the last time, had given a listing of tribes. But even in this census, the groups that were identified by a distinct tribal name were classified in terms of their religion. Only those that were not converted to any religion—Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, or Jainism—were called tribals. Hutton went to the extent of calling tribal religions residuals that were yet to enter the temple of Hinduism.

When India won independence, and the constitution of the Indian Republic was being drafted, special provisions were introduced for the protection of the tribes and the so-called oppressed groups within the Hindu caste system. The constitution ordained special lists—called schedules—of such groups for purposes of granting them special privileges with a view to ameliorating their conditions and improving their socio-economic profile.10

It must, however, be said that the Constitution of India nowhere defines the word tribe. Article 342 of the Constitution says just the following:

The President may with respect to any state or union territory, and where it is a State, after consultation with the governor, thereof, by public notification, specify the tribes or tribal communities or part of groups within tribes or tribal communities which shall for the purposes of this constitution be deemed to be scheduled tribes in relation to that state or union territory, as the case may be.

Article 366 (25) defines the schedule tribes as follows:

Scheduled tribe means such tribes or tribal communities or parts of groups within such tribes or tribal communities as are deemed under article 342 to be scheduled tribe for the purposes of this constitution.

In the absence of any definition, the bureaucracy took recourse to the 1931 census, which had listed the castes for the last time and prepared two schedules—one for the tribes and the other for the castes. Those groups included in these lists are called Scheduled Tribes (ST) and Scheduled Castes (SC) respectively.

As was expected, the lists were not satisfactory and many groups that were not included in them sought their inclusion. It is at this point that the need for a clear-cut definition of the term Tribe was felt.

The Government of India set up a Joint Parliamentary Committee under the Chairmanship of Shri Anil K. Chanda, which proposed (1967) the following five criteria for judging the eligibility of any group as a tribe:

- Indication of primitive traits

- Distinctive culture

- Geographical isolation

- Shyness of contact with the larger community

- Backwardness

The official documents nowhere provide any indicators for each of these variables to develop an objective index. Different people have interpreted each of these variables differently.

Objectively speaking, the first criterion—namely, indication of primitive traits—is broad enough to cover all the other criteria: the primitives are those who have a distinct culture of their own, live in relative isolation, and therefore, fight shy of contact with the outsiders, and as a consequence of their isolation, they have remained backward. What, then, are the additional ‘Primitive’ characteristics to be included in the first criterion?

Primitiveness of a community is a comparative term, as it is opposed to modernity—yet another term that is variously defined. Broadly speaking, primitiveness indicates the lingering state of backwardness of a group and its inability to catch up with the mainstream in terms of socio-economic development. Primitiveness may be attributed to lack of education, narrow worldview or Weltanshauung, ethnocentrism, cultural prejudices, lifestyle, and socio-economic inequities. No present-day society, however backward and underdeveloped, fits the nineteenth-century stereotype of a primitive, stone-age culture. Construction of approach roads, opening of schools, use of modern means of agriculture (such as tractors, chemical fertilizers), use of national currency for monetary transactions replacing barter, and even the use of radio transistors, and now the mobile phones, have changed the material cultural profile of the so-called primitive communities.

What then are the key component variables of the concept ‘Primitive’?

The same is the difficulty with the concept of distinct culture. Can one not argue that primitiveness, as implied in the first criterion, will result in a distinct culture? Also, there can be a distinct culture, but it need not be primitive.

The criterion of geographical isolation is also untenable. With increasing connectivity caused by tremendous improvements in the area of transportation and communication, there are a few islands of relative isolation with difficulty of access. Revolutionary changes brought about by advances in information technology have broken the communication barriers and reduced isolation. Democratic governance in the country has greatly contributed to the breakdown of isolation. The electoral process involves campaigning by various candidates in their respective constituencies, including village communities that are otherwise not regularly contacted. Such contacts not only break geographical isolation, but also help enlarge the cognitive horizons of the common people. They come to know of political parties, leaders, and political issues. And they are also dragged into the political process either as fellow campaigners or as candidates for posts for different legislative bodies and local-self governments, such as panchayat samities and panchayats or co-operative societies. No doubt, geography still hinders effective interaction in some areas, but the situation is vastly different from the days when savagery and barbarism were perpetuated because of lack of contact.

No groups fight shy of contact with others. Of course, shyness as a social norm of courtesy towards elders, or amongst people of the opposite sex, is not to be confused with the shyness exhibited by the people living in the non-civilized world. That is a matter of the past. Sale of rural products, such as dairy items and cash crops in urban markets, by these claimants of tribal status clearly indicates the entry of these people in the regional economy.

It is the concept of backwardness that seems, however, to provide a dependable list of variables for developing a suitable index. But this might as well apply to many other non-tribal village communities. Backwardness is either an attribute of a territorial community or of individual families within it, and not of any biotic community. There are tribal areas in the Northeast which are urban, and there are many individuals belonging to the so-called tribal groups who have excelled in business, or academics, or in politics. The homogeneity of backwardness implied in the definition does not correspond with the actually existing condition.

The new tribal policy draft document, issued by the Government of India in July 2006 acknowledged the redundancy of the five criteria. It boldly asserts: ‘… all these broad criteria are not applicable to scheduled tribes today. Some of the terms used (e.g. primitive traits, backwardness) are also, in today’s context, pejorative and need to be replaced with terms that are not derogatory’ (Para 1.2). In Para 20.4, it says that ‘Other more accurate criteria need to be fixed’. It is significant that the tribal policy acknowledged the need for a process of ‘descheduling’ so as ‘to exclude those communities who have by and large caught up with the general population. Exclusion of the creamy layer among the scheduled tribes from the benefits of reservation has never been seriously considered. As we move towards, and try to ensure, greater social justice, it would be necessary to give this matter more attention and work out an acceptable system’ (Para 20.6).

The question that arises is: at what stage does a tribe cease to be a tribe? Is it that a tribe remains a tribe forever? It can be argued that all segments of the world population was at one stage or the other a tribe, and in due course of time merged their identities to form part of one or the other civilization.

The groups that are regarded as tribes in India today can be broadly classified into the following categories.

I. Tribal Communities Living in Their Original Habitat

- Relatively Isolated: Retaining most of the characteristics of their social organization, despite some culture contact (the Kadars);

- Two or More Tribal Groups Living in the same Area: Such groups maintain mutual contact, and yet remain isolated from other non-tribal groups, demonstrating some sort of cultural symbiosis (the Todas, Kotas, and Badagas);

- Living with Other Tribal/Religious Groups in the Same Community: These have sub-types:

- followers of their own religion, retaining most characteristics of their social organization and culture;

- while remaining separate from other religious groups, accept the leadership and domination of the other groups;

- those moving towards Hinduization;

- Hinduized;

- Baptized in religions other than Hindu

- towards conversion; and

- converts

II. Tribal Groups Living Away from Their Original Habitat

- Settled in Neighbouring Villages:

These could also be classified into five categories as in I (c):

- followers of their own religion, retaining most of the characteristics of their social organization and culture;

- while remaining separate from other religious groups, accept the leadership and domination of the other groups;

- those moving towards Hinduization;

- Hinduized;

- tribes that have been forced the degraded status of untouchables;

- those enjoying high status; and

- those assigned status in the ranges of the Hindu hierarchy.

- Baptized in religions other than Hindu

- towards conversion; and

- converts

- Living in separate villages in other areas

such as Bhoksa of Nainital

- Settled in industrial centres or cities, or in tea plantations, military recruits, and others.

This distinction of the original habitat seems to be very relevant in the sense that such groups are not migratory, and therefore, there is a greater degree of territorial attachment. Like the Maoris in New Zealand, such indigenous people have ancestral claims, and despite their being modernized, their autochthonous roots cannot be challenged. As against these, the migrating communities lose their attachment to their parental land and show a greater degree of adaptability. All those who constitute the mainstream of a multicultural society have a queer mix of the great tradition and the little parochial traditions. Their being tribal is a matter of the past; therefore, Col. Tod or Sherring calling all groups—Rajputs, Brahmans, Gujars—tribes11 becomes less significant in today’s context, because these groups have entered the fold of civilization and even contributed to its richness. Even illiteracy does not block this transition. Those who are part of civilization also have stratification in social, economic, and political terms.12

The difficulties are now being created as some of the groups which earlier made all attempts to become part of mainstream society by adopting new religions—Hinduism, or Islam, or Christianity13—have begun reasserting and reviving their past and claiming a tribal status. This is being done more to avail of the privileges that are granted to the tribals. It is being described now as a process of Reverse Sanskritization. Such groups do not fulfil the criteria set by the government, but they insist that the same criteria are also not applicable to many groups that are already included in the list of scheduled tribes. They are using a double-edged weapon: either include us as our present life style is identical with some of those included in the schedule, or de-schedule those who do not deserve to be there.

Caste: Varna And Jati

Another ascriptive group, smaller than race and almost similar to ethnic group, and in many ways corresponding to the tribe, is caste. In most sociology texts, caste is contrasted with class as a structural type and is defined in a tautological manner: ‘Class is an open caste, caste is a closed class’. The point underlying this distinction is the fact that while in class membership remains fluid—people can move up or down—no such mobility is allowed in caste.

Since there are no gatekeepers to maintain the boundaries of a class and no specific nomenclature exists for individual classes’,14 it is not easy to identify them. Of course, a child is born into the perceived class of its parents, but through his deeds, a person can move out—rise or fall, or even stay where one was born. And this status is determined at the level of the family. In the case of caste, such mobility is theoretically denied’,15 and the status is determined at the level of caste—a group consisting of families—and not at the level of family, as in class.

Class and caste are, thus, interrelated concepts. But for purposes of clarity, we shall deal with them separately. In doing so, we suggest that class is a category, while caste is a group in the sociological sense.

In sociological literature, caste is mostly treated as a cultural phenomenon exclusive to Hindu India. We take the position that for sociological analysis, caste should also be treated as a structural term, of which Hindu caste is one specific manifestation.16

This requires us to distinguish between tribe, caste, and class.

In our discussion on the concept of tribe, it was stated that there is a lack of consensus on the concept, because tribes throughout the world have undergone tremendous changes as a consequence of centuries of culture contacts, both within the region and with the colonialists from other continents. All tribes of today are not preliterate, nor are all followers of animism, nor are they at the same level of primitive economy or technological development. Small tribal groups living in their original habitat—the autochthones or the indigenes—continue to be an in-marrying group, that is, endogamous.

It is endogamy that makes a particular tribe similar to a caste, because it is endogamy that becomes the foundation for the ascriptive status—a status by birth. But what distinguishes a caste from a tribe is the fact that while the entire tribe functions as an endogamous group, a caste is a part of a system consisting of a number of similar such groups. In other words, the concept of caste has two components: (i) caste as a unit, and (ii) caste as a system. Even in the Indian context, this distinction has not been followed by many. Rather than bothering about what constitutes a caste unit, most treatises on caste have focussed on inter-caste relations. The criticism of the Indian caste, for example, mostly rests on this premise. That is why, what is highlighted is hierarchical arrangement, and the practice of untouchability and oppression by the upper castes. In this process, many analysts and critics of caste ignore defining a caste unit, which is taken for granted.

Since India is regarded as possessing a well-developed caste system, we shall analyse these aspects in the Indian context and then offer a definition.17

The Many Uses Of The Term Caste In The Indian Context

Caste in India is a much misunderstood term. It is employed for different kinds of groupings, not only by the common people, but also by social scientists, including sociologists. It has been, and is being, used to refer to:

- varna, which divides Hindu society into four major divisions in which various castes, that is jatis, are clubbed together;

- gotra, which is an exogamous group within a caste; and

- even to a family title (Bhandarai or Khajanchi), or to a regional group (Bengali, or Punjabi, or Madrasi).

Sociologically, these are all wrong usages. For example, Brahmin is not a jati, it is a varna, just as Kshatriya, Vaishya, and Shudra in the Hindu system of Chaturvarnya—four-varna division. Of course, one can safely say that the Brahmins marry amongst the Brahmins and the Kshatriyas amongst the Kshatriyas and so on, and therefore, they are also endogamous, which is the key attribute of caste. But this is a false interpretation. Using the same argument, one can say that since Indians marry Indians, all Indians belong to a single caste called Indian. Endogamy becomes a meaningful category when it is used for the minimally endogamous group—that is, when groups below it are exogamous. Families, and gotras are groups within a caste and they observe exogamy; gotras and families within a caste marry outside but within the same caste of which they are a part.

A gotra, or a family title, is different from caste; the regional appellation (such as Indoria or Singhania) only suggests the region or a settlement a person hails from. No one marries, exceptions apart, in a gotra.

A caste, on the other hand, consists of several families belonging to different gotras, or family titles. There are also avatanks, pravars, etc., that distinguish different lineages and clans from each other. All such groupings within a caste are out-marrying units. Technically, they are called exogamous (marrying outside, or not allowing marriage within). But the caste is an endogamous (in-marrying, allowing its members to marry within) group.18

There are five main sources of confusion that create difficulties in defining caste.

- Difficulties arising from a variety of social organizations. It is important to remember that all castes were not built on the same model. The system has grown slowly and gradually, and different castes had their different origins. There is a wide variety of practices in different regions and in different castes within the same region.

- Difficulties emerging from ignorance about, or indifference towards, other castes by the local people. In the caste context, people are grouped in different ways. The term caste is used, by ordinary people for a varna, a sub-caste, a religious group, or even a regional group. It is also used for exogamous groups within a caste.

- Difficulties emerging from the confusion between the Ideal and the Real. The ideal of the four varnas is no longer clearly applicable in today’s context because all the castes of today cannot be said to be the descendants of the original four varnas. Locating the new entrants into the four-fold hierarchy is not easy.

- Difficulties emerging from the fluidity in caste. Contrary to the prevalent notion that castes are rigid, students of Indian society have discovered many processes in operation that have changed the boundaries of caste. Instances can be found where analogous castes have amalgamated. There are also cases where a caste has been split into two or more groups, first as factions and later as independent castes, cutting all ties with the parent body. At times, the people who had been ostracized for breaking the rule of endogamy have created castes.

- Difficulties emerging from a common nomenclature. There are castes that are better known by the name of the occupation pursued by their members, or the locality from which they migrated, or the language they speak. There is also widespread effort by castes, or certain individuals within the group, to adopt a new name, or use a surname associated with other groups.

Definitions of caste are many. Some have defined caste as a unit; others have talked of the caste system. There are others who have combined the traits of the unit and the system without making any clear-cut distinction. By using the term both for caste (that is jati) and varna, as also for caste and sub-caste, a good deal of confusion has been created. There exists no vernacular word for sub-caste.

In defining caste as a unit, we follow S. F. Nadel.19 According to him, every designated status (Nadel used the term ‘role’) has a hierarchy of three different types of attributes, namely, ‘peripheral’, ‘sufficiently relevant’, and ‘basic or pivotal’. Attributes are called ‘peripheral’ when their ‘variation or absence does not affect the perception and effectiveness of the role’. A ‘sufficiently relevant attribute’ is that where its variation or absence ‘makes a difference to the perception and effectiveness of the role, rendering its performance noticeably imperfect or incomplete’. Those attribute/s are called ‘basic’ or ‘pivotal’ whose absence or variation changes the whole identity of a role (Nadel, 1957: 31–32). A content analysis of the prevailing definitions and descriptions of caste led Atal (1968) to define caste as a unit in terms of these attributes as under:

- Basic or Pivotal Attribute: Minimal endogamy

- Sufficiently Relevant Attributes:

- Membership by birth

- Common occupation

- Caste council

- Peripheral Attributes:

- Name of the group and special naming pattern of its individuals

- Dress diacriticals

From the above discussion, it follows that a caste, that is jati, should be understood as a minimally endogamous group.20 The prefix minimally is important. Below this level, the group is divided into exogamous groups. Without this qualification, caste would lose its significance. All the groups above this level are equally endogamous, but cannot be called caste.

There is another point that needs to be highlighted. A group’s endogamous character should be understood in terms of its capability to provide mates; that is to say, ‘marriage within is prescribed and possible’. But this does not mean that marriages outside cannot take place. When a caste splits, the splinter groups allow intermarriages. The pattern of hypergamy (Anulom21 in Sanskrit) or hypogamy (Pratilom in Sanskrit) also does not defy definition since hypergamy or hypogamy is practised ‘in addition to’ endogamy. Marriages do take place within and between castes. As long as the group concerned allows marriage within it, the term endogamous can be used for it. Where endogamy is total, not allowing any hyper or hypogamous unions, it should be called ‘isogamy’—a case of rigid endogamy. This may be an ideal, but in reality inter-caste marriage along with intra-caste marriages do occur and are, in many cases, the rule rather than an exception. The prefix ‘minimally’ is used to indicate that below the level of caste, there are no endogamous units.

Thus, the basic attribute of a caste unit is endogamy. The group has to be minimally endogamous. It may follow it rigidly and become (isogamous), or it may allow both marriages within and outside through hypergamy or hypogamy. Built into the concept of endogamy is the point that such endogamous groups are divided into exogamous groups, called clan or gotra or got.

The visibility of caste as a group is heightened when (a) all its members are recruited by birth alone—that is, when the group becomes completely isogamous; (b) the members pursue a common occupation; and (c) when the group has its own traditional council (Panchayat) to enforce caste norms over its members; (d) If the caste has a distinct name, not shared by any other group; (e) and if its members can be identified by distinctive dress pattern or naming pattern or certain practices, then it becomes easier to distinguish one caste from the other. It may be said that while endogamy is the basic attribute, other attributes—(a), (b) and (c)—mentioned above are ‘sufficiently relevant’ in the sense that their presence enhances the visibility of the group. Attributes (d) and (e) are ‘peripheral’ which definitely enhances visibility, but their disappearance does not cause major crisis in identity. When any of the sufficiently relevant attributes disappears, caste identification becomes somewhat difficult, but the continuity of the group is maintained as long as it remains minimally endogamous.

Sociologists should also be careful in the use of the word sub-caste. Those who use the word caste for the four varnas of the Hindu society, use the term sub-caste for all the jatis. We have suggested that use of the word caste for varna is wrong, because the latter is a caste cluster. Therefore, the term caste is the English rendering of the term jati that is in vogue in India. The term sub-caste, accordingly, should not be used for all the sub-divisions within caste, but should only be used for those that fulfil the basic condition of endogamy and have internal division into a number of inter-marrying exogamous groups.

In other words, the term sub-caste should be used only for those groups, which have split up and become endogamous groups in themselves, but which still retain some links with the original unit. This split may take place either because a significant section moves to a distant place, or adopts a different occupation. For example, the various gypsy castes of Southeast Punjab and Uttar Pradesh have become endogamous units though they were one group originally. The 1931 census gives the example of the Khatik (butcher) caste, which got split into Bekanwala (pork butcher), Rajgar (mason), Sombatta (ropemaker), and Mewfarosh (fruiterer). Such sub-castes continue for some time to have inter-marital relations, but finally stop intermarriages and become independent castes. Another good example is of the Kaibarttas of Bengal (in UP they are known as Kewat). This group might have originally been a tribe. After coming into contact with other castes, this group divided itself occupationally into two groups. One group took over the calling of fishermen and the other of agriculture. The fishermen dealt with jal (water) and were called Jaliya Kaibarttas, and the other group handling the hal (plough) took the name of Haliya Kaibarttas. Since ploughing was rated higher, the Haliya Kaibarttas gave women in marriage to the Jaliyas, demanding high bride price, but did not accept wives from them. Of course, this instance of hypogamy (Pratilom) seems to be an exception, because generally people of higher caste take wives from the lower castes (hypergamy) but do not marry their daughters in the lower group. In due course of time, the two Kaibartta sub-castes became separate endogamous groups, and the Haliya Kaibarttas even changed their name to Mahishya.

A caste is to be understood as a group within a society. It is recognized only in relation to other such groups in the society with which it interacts in the economic, political, social, and ritual spheres of life. This network outlines the working of the caste system. Thus, it is logical to define the caste system as

- a plurality of interacting endogamous groups (jatis) living a common culture (basic or pivotal attribute);

- these castes are supposedly arranged hierarchically (sufficiently relevant attribute);

- there exists a broad division of labour between them, because of occupational specialization.

The presence of all these three attributes makes the caste system highly visible.

In this usage, a tribe can be distinguished from caste in the sense that while it has all the attributes of caste as a unit, it functions as a system, as there are no other castes to interact within the same community; in other words, the attributes of the caste system do not apply to a tribe. It is only when a tribe comes closer and begins to share the same village with other endogamous groups that the system (tribe) is reduced to the status of a unit. That is the reason why tribes that have settled in rural India are treated as castes by the local communities. Their being a tribe is only a reference to their past; structurally, they function as castes within the caste system of the region. It is in this sense that the claims of groups like Gujars in Rajasthan for a tribal status should be judged. In practice, they claim to be Hindus and behave vis-à-vis other groups as a caste. But they invoke their tribal past to gain an entry into the list of scheduled tribes.22

Structurally speaking, the word tribe should be used only for such communities that fulfil the basic attribute of a caste but not of the caste system.

Those who regard caste as a ‘structural’ feature have argued that the caste system is found in non-Hindu contexts as well. The Paikchong of Korea and the Ita of Japan had a status similar to the ‘Shudras’, and therefore Korean and Japanese societies exhibit rudimentary forms of the caste system. Similarly, those who studied the Deep South of the United States of America have talked about the white-black relationship in caste terms.

A Gond in a Madhya Pradesh village, where Gond is treated as one of the castes.23

(Courtesy: © Yogesh Atal)

Nearer home, we find that despite conversion to Islam or Christianity, the converts have carried their castes and thus stratified these religions along caste lines. This is also true of Sikhism, Jainism and Buddhism, which rose as protest movements against Brahmanical caste system but remain divided along caste lines. All these instances indicate that caste as a structural unit should not be confused with its particular manifestation in a given cultural setting.

Caste system is found in India in religions other than the Hindu. ‘A clear-cut Varna division,’ writes S.C. Dube, ‘is not found among the Christians and Muslims, but a distinction is made between high-caste and low-caste converts. The former identify themselves as Brahman Christians or Nayar Christians, or as Rajput or Tyagi Muslims’. Writing about the situation of converted Christians, Dube says:

“The Indian Church now realizes that approximately 60 per cent of the 19 million Indian Christians are subjected to discriminatory practices and treated as second-class Christians or worse. In the South, Christians from the Scheduled Caste are segregated both in their settlements and in the Church. Their Cheri or colony is situated at some distance from the main settlement and is devoid of the civic amenities available to others. In church services they are segregated to the right wing and are not allowed to read scriptural pieces during the service or to assist the priest. They are the last to receive the holy sacraments during baptism, confirmation, and marriage. The marriage and funeral processions of Christians from the low castes are not allowed to pass through the main streets of the settlement. Scheduled Castes converted to Christianity have separate cemeteries. The Church bell does not toll for their dead, nor does the priest visit the home of the dead to pray. The dead body cannot be taken into the Church for the funeral service. Of course, there is no inter-marriage and little inter-dining among the ‘high-caste’ and the ‘low-caste‘ Christians.24

Among the Muslims, too, a distinction is made between the original and the convert Muslims. In common parlance, people talk of sharif zat (well-bred, or of higher caste) and ajlaf zat (common or lower caste). These distinctions govern decisions regarding marriage and inter-dining. Also, the converts continue practising their jati-linked occupations, which heightens the separate identity, as in the caste system. Mention may be made of Muslim castes such as Julaha, Bhisti, Teli, and Kalal; there are also Hindu tyagi and Muslim tyagi, Hindu Gujar and Muslim Gujar.25 It is also significant that the Muslims are also divided into four divisions, namely, Syed, Sheikh, Mughal, and Pathan. And these function as endogamous groups. In fact, among the Muslims, endogamy is much more restricted because both cross-cousin and parallel cousin marriages are preferred, and they do not have the gotra system of exogamy.

It should be clear from the above that the system of stratification in a caste society takes caste as a unit. But the stratification is region-based. Even in the case of India, the four-fold division of the varna system does not help in distributing more than 3,000 castes26 in those neat categories.27 There are many new entrants to the caste system that defy any such placement.

Constructing caste hierarchy is not an easy task. Fieldworkers studying the present-day caste system in rural India attempted to construct a ritual hierarchy of castes—as caste is supposed to be governed by considerations of ritual purity and pollution—on the basis of their observations. In fact, two different ‘theories’ were employed: these are called attributional and interactional theories of caste ranking.28 It was Mckim Marriott who attempted a comparison of caste ranking in five regions in India and Pakistan, and in that process employed these theories which he regarded as ‘hypotheses’. According to Marriott, the Attributional theory ‘runs strongly to the view that a caste’s rank is determined by its behaviour or attributes’ (1959: 92). The Interactional theory ‘holds that castes are ranked according to the structure of interaction among them’; he identified two major ritual interactions: the ritualized giving and receiving of food, and the giving and receiving of ritual services (ibid.: 96–97). It was Marriott’s contention that ‘South Indian ranking may be more attributional while North Indian ranking may be more interactional’ (ibid.: 102).

Doing fieldwork in two villages of Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh, Atal employed Marriott’s technique and found that the combination of both attributional and interactional data was necessary to construct a ritual hierarchy of castes as it prevails. And this is only one type of stratification based on ritual considerations. The hierarchies so constructed are not unilinear, and do not exactly fit the varna scheme. In tables 15.2 and 15.3, we produce the caste hierarchies in the two villages (for details, see Atal, 1979: Ch. 5).

The system of stratification in villages in terms of caste has its limitations, because castes in villages are represented only by a limited number of families belonging to that caste. In fact, the caste unit is a horizontal group spreading in a large number of contiguous villages, but inter-caste interactions operate both at the village level and in the region as a whole. The works of Dube, Chauhan, and Majumdar suggests that in a village, what we notice is a hierarchy of blocs and not of castes. Within the blocs, or tiers, some castes may be higher or lower, or on the same plane. Thus, even the castes amongst the Brahmins are differently ordered, so are the castes that belong to the lower strata. For example, there are a number of castes associated with leather work, but all of them do not enjoy the same status; they are also ranked.

Table 15.2 Ritual Hierarchy of Castes, Kheri, Rajasthan

Untouchability is also a relative term. It varies from allowing access to the kitchen, or accepting food (even food is differently classified in terms of pollutable and not pollutable—kachcha and pakka) and water, and physical touch. Clubbing all the lower castes either as ‘untouchables’ or ‘oppressed’ is not empirically supported, as there are different degrees of untouchability, and types of oppression. The severest form of untouchability was found in relation to the caste that was engaged in the most degrading task of the removal of night soil. This is, however, not to deny the existence of ill treatment meted out to the people of the lower strata. Also important is the point that even amongst the groups that are said to belong to the lower strata, inter-caste relations exhibit tendencies of discrimination and untouchability. Hierarchical relationships, for example, also exist amongst people who are all traditionally engaged in occupations related to the removal of dead animals and the use of leather.

The Dominant Caste

Village studies carried out by sociologists and social anthropologists in India brought convincing evidence to suggest that ritual hierarchy needs to be differentiated from the social hierarchy of dominance. In the social and political spheres, we are told that the power did not rest with the Brahmans who are regarded as ritually ‘superior’ to others. The kings or nobles, for example, came from the Kshatriya varna; and many invading groups who overwhelmed the local populace and became rulers allocated themselves the status of a Rajput. The Meena—regarded as an indigenous tribal group—got divided into Jagirdar (feudal) and Chowkidar (Meenas). The same has happened with certain sections of the Gujars, the Badgujars and Pratihars among them identified with the ruling group.

Table 15.3 Ritual Hierarchy of Castes: Khiria, MP

Source: Yogesh Atal, 1979; pp. 130 and 134 respectively for the two tables.

To highlight this important distinction, M. N. Srinivas proposed the concept of dominant caste.29 He regarded ‘numerical strength, economic and political power, ritual status, and western education and occupations’ as ‘the most important elements of dominance’ (1959: 15). Besides these, he mentions (i) ‘the capacity to muster a number of able-bodied men for a fight’; (ii) ‘reputation for aggressiveness’; and (iii) ‘abusing, beating, gross under-payment and forceful gratification of the sexual desire with women of non-dominant castes’ as relevant factors. Such dominant castes, according to him, serve as ‘vote banks’.30

The concept of dominant caste, as advanced by Srinivas, is a mere listing of the attributes, and if all such elements are found in equal measure in any particular caste, certainly it would qualify as a dominant caste. But in actual field situations, such is not the case. Those who employed Srinivas’ concept in actual field conditions found that numerical preponderance need not always go with high ritual status of a caste. Moreover, the numerical strength of a caste varies from village to village, because in any given village, a caste is represented by a small number of families belonging to it—it is usually a family-writ large group. Thus, what happens in day-to-day village politics is very different from the politics of the region in which the village is located. In the democratic set-up, it is the numbers that count and not ritual status or economic power. People with high ritual status, or greater wealth do take leadership roles and even manage to get tickets to contest elections, but it is the numerical preponderance of a caste that defines its status as a vote bank. Field studies also suggest that larger groups lose their cohesiveness because of factionalism and different political preferences.

This concept was commented upon and criticized by Dube, Atal, and Oommen, among others, by presenting empirical evidence from village India that refused to be caged in it, and also pointing out theoretical ambiguities (Dube, 1968; Atal, 1968; Oommen, 1970). Oommen sums up the key criticisms of the concept by saying that Srinivas made the following assumptions, all of which are questionable: ‘(1) that a dominant caste is a united group; (2) that power is concentrated in one or another caste; (3) that power is mainly an ascriptive attribute; and (4) that village power structure tends to be stable overtime’. Quite in tune with the observations made by Dube and Atal, Oommen reiterates that ‘… castes with the requisite resources to be dominant are divided into hostile factions thereby reducing their potentiality to emerge as dominant castes; that the segmental character of caste system makes for power dispersion and it imparts a certain measure of autonomy to all castes; that persons with relevant personality traits acquire and exercise power even when they do not belong to dominant castes; and that the dominance view of power contains erroneous assumptions regarding the … human nature and that it does not account for the productive functions of power’ (Oommen, 1970: 82). There is the additional point that Srinivas talked of the dominant caste in the context of the village Rampura31 studied by him. But a village is not an isolated whole. Caste dominance needs to be seen in a regional or a sub-regional perspective. The old accounts of the caste system and of the atrocities committed by the so-called dominant castes relate to the region as a whole. Thus, a numerically preponderant caste in a village may not be populous in the region; similarly, a numerically preponderant caste in a region, or a sub-region, may have a minority in a given village. The DMK movement in the South was against the Brahmins of the province—and here the attack was on the caste cluster (that is, varna category) as a whole and not on a particular Brahmin caste.

The Concept of Vote Bank

In contemporary politics when political parties talk of vote bank, or of caste dominance, they refer to the electoral constituency—consisting of several settlements—and not to any single village; and quite often they use it for a caste cluster, such as SC votes, Rajput votes, Muslim votes; none of these qualifies as a caste in the sociological sense of the term. It appears that Srinivas tried to explain the then existing pattern of caste-related violence, the oppression of the poor and the lowly by the rich and powerful feudal chiefs or landlords. Coming from the pen of a celebrated sociologist, this package, namely, the concept, the attendant terms (such as ‘vote bank’), and some of the despicable practices (such as sexual exploitation of women of the lower strata) had an easy acceptability. The unintended consequences of this uncritical acceptance were not foreseen and the critique of the concept was somewhat ignored.

The message that the concept conveyed, that of the significant role of caste in politics—local and national—was picked up by political strategists and political journalists. The strategists employed tactics to create caste-based ‘vote banks’ and the political journalists and some social scientists used this framework to analyse election results. Caste became an explanatory variable on false premises, but has become a guiding principle in the election strategies of all political parties. Despite all talks of secularism, and despite decrying caste, such efforts have led to the strengthening of caste on frontiers other than the traditional. Caste identities have gained in prominence in terms of the ‘peripheral attributes’ whereas the ‘sufficiently relevant attributes’, have disappeared, and even the core attribute is getting somewhat diluted. In the process, a unity came to be fostered at the level of a caste cluster—the Jat vote, the Yadav vote, or the Brahmin vote, forgetting that the real operative caste at the regional level is different from such a cumulative category.

The success of a Jat or a Brahmin from a given constituency is generally attributed to the numerical preponderance of that group. What is forgotten is the point that using the same tactics, different political parties put up candidates from the same cluster that is regarded as preponderant. Quite naturally, anyone winning the election will hail from that group, but his victory cannot be attributed solely to the numerical strength of that caste cluster. This is because if there are several candidates from the same caste, each one of them would be getting only a part of that so-called ‘vote bank’ and will have to depend on support from other caste groups. This fact demolishes the myth of the vote bank. It is allright for a political strategist to create a vote bank on the basis of a caste-based unity, but it is wrong to assume that the people who supposedly constitute that vote bank would oblige the strategist.

On the positive side, it can be said that on the political front, where numbers matter, efforts are being made to use the idiom of caste to create solidarity at the level of caste cluster, both regionally and nationally. Such groups emerge as regional or all-India organizations and are supra-caste in character. There have been studies of such organizations and movements focusing on their contribution to the political process and to social reforms relative to caste. If several castes are congregated into a relatively smaller number of caste clusters and become inter-regional in their composition, then the old picture of caste in India will get drastically changed. This may mean a new incarnation of caste.

In the village social structure, one can find ritual hierarchy as well as other forms of stratification based on power and wealth. The same caste may have families that belong to different economic classes. Also, people may maintain their endogamous boundaries but belong to economic strata that cut across castes. Class and caste are, thus, not polar opposites and provide different vantage points for stratification.

Class

So far we have discussed the identifiable groups whose membership is defined by the fact of birth. These are race, tribe and caste. We now move to discuss a social category called Class which is open—through achievement, people can enter a new category. Achievement is used here as a neutral word—a person can achieve success or failure. Those who succeed in life rise higher, and those who do not, go lower. Thus, the element of hierarchy is present even in class-based stratification.

Those who talk of ‘equality’ in the class context are underlining the fact of openness—suggesting that there are no gatekeepers to restrict entry into the class. Louis Dumont distinguished caste society from class society by designating them as Homo Hierarchicus32 and Homo Equalis. But this is an exaggeration; Dumont fails to distinguish between a group (such as caste) and a category (such as class).

Let us briefly note the difference between race, tribe, and caste before we proceed to analyse class.

In case of race, the physiological characteristics of its members are so very prominent that they can easily be distinguished from those who do not belong to it. People of the same race may be divided into several different societies—not only tribes or primitive communities, but also big societies. Here again, ascriptive criteria are employed to ascertain membership. People belonging to the same race demonstrate greater similarities in their physiognomy. It is, however, not necessary that people of a given race constitute a single society. As noted earlier, the world population is divided into three major races, Cuacasoid, Mongoloid, and the Negroid, but the world consists of several nation-states. There are as many as 192 member-states of the United Nations. This fact alone suggests that race is not coterminus with society or culture.

Smaller societies—such as a tribe—are constituted by people of a single race. They have a common lifestyle—speaking the same language, practising the same religion (or animistic rituals and magic), and having an endogamous boundary. The community has its gatekeepers to distinguish between members and non-members. The point is that several tribal societies may belong to a common race. Tribes are found amongst all races.

A tribe may become a caste when it joins similar other endogamous groups living in a common area and sharing a common ethos and culture. Such societies are not only multicultural, but also multi-racial. India is a good example of a multi-racial society. Caste membership is defined by birth and the rules of endogamy are followed rather strictly. A caste system is defined as a system of interacting endogamous groups sharing a common habitat. Castes are found not only among the Hindus; as a social structural unit it is found in other social systems as well.

Many of those who have written on class also refer to endogamy as one of the criteria for its determination. Thus, Johnson writes,

A social class … is a more or less endogamous stratum consisting of families of equal social prestige who are, or would be, acceptable to one another for ‘social’ interaction that is culturally regarded as more or less symbolic of equality; as the term ‘stratum’ suggests, a social class is one of two or more such groupings, all of which can be ranked relative to one another in a more or less integrated system of prestige stratification (1960: 469–70).

Endogamy in the context of class, however, has a different connotation. To quote Johnson again: in the framework of class ‘Men tend to marry women not too different from themselves in family background and education’. Further, ‘the most decisive mark of class equality between families is the fact that they will accept one another’s children in marriage without feeling, on either side, that the match is socially inappropriate’ (ibid.: 471). This conception of endogamy is similar, but not the same as caste endogamy. In the case of caste, it is membership to that group—which is by birth—that is more significant and the emphasis is laid on marrying within the group. In the case of class, the key consideration is the economic status of the family, which is largely judged in terms of the ‘occupation’ of the male members in patrilineal societies. To be sure, even in the caste context marriages are arranged between families of identical social status within the caste; the parents of the girl prefer to get her married into a family of their rank or of a superior rank. Thus, class becomes an additional factor. Students of caste have reported the existence of classes within the caste.33

In the case of class too, birth does play a role, in the sense that the class of the parent becomes the launching pad for social ascendancy for the child. A new born belongs to the class of his parents, and thus his initial status remains ascriptive. But the child in his later career can either rise up or fall through his deeds—the status thus obtained is achieved status. In caste, the status at birth remains unchanged; not so in the case of class. The twin concepts of class and caste are thus not polar opposites as it is generally made out to be.

But the similarity ends here. The major difference is that while caste is a group, class is not. It is a category. Unlike a group, a class is a construct either concocted by a social analyst or notionalized by the people. Marx’s classification of societies into bourgeoisie and proletariats is one such example. The division of so-called capitalist societies into upper class, middle class and lower or working class is also an analytical classification. Anthony Giddens—a British sociologist—for example, defined upper class on the basis of ownership of property in the means of production, middle class on the basis of possession of educational and technical qualifications, and the working class on the basis of possession of manual labour power. As is evident, this classification is heavily influenced by Marxian thinking.

In America, professions are broadly classified into white-collar and blue-collar jobs. The division of society into upper, middle, and lower classes, and the further division of each of the classes into sub-strata, is also made by sociologists. Common men generally refer to the three main classes, but the indicators they use are not well defined or commonly agreed upon. It is usually considered that developed societies generally have a huge middle class, and that societies tend to encourage upward mobility.

The classes, unlike groups, are fluid in terms of membership; they neither have well-defined boundaries, nor do they have any gatekeepers to allow or deny entry. It is families which are said to belong to a class. In developed societies, where the nuclear family is the norm, it is mainly the status of its head that helps identify the class status of the family. But such families need not be clustered together, nor do they need to have an organized network. It is only the pattern of interaction of the family—the place where it stays, the school where its children are sent, the clubs the family joins, and the overall lifestyle (indicating the affordability)—that becomes symbolic of class equality.

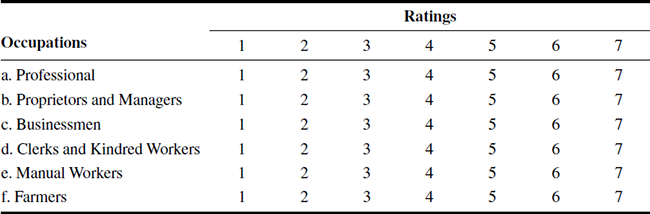

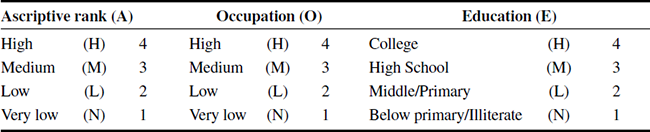

Who belongs to a given social class is arbitrarily determined. An overemphasis is given to occupation. These are ranked in terms of prestige, salary, kind of work, etc. Researchers have developed indicators to classify families in their sample populations. Some others have used the technique of asking respondents about the ranking of families or individuals to assign them a class status. In sociological research, this class status is also known as ‘socio-economic status’ or SES.

Since class is an analytical category and not a group, in real societies it is not easily identifiable. People use the concept rather vaguely. One finds a tendency among people to generally claim a middle class status. As a sample of such usage, we take Pavan K. Varma’s popular book titled The Great Indian Middle Class.34 Varma writes:

In the course of this work I have deliberately avoided the not so uncommon obsession with computing the exact size of the middle class and its precise income and consumption parameters …. My approach has been to take this class as a clearly identifiable but numerically broad-brush identity … [1998: xiii].

In an earlier exercise, historian B. B. Misra also used the categories without bothering about estimating their size. He classified the Indian population in a historical perspective into various sub-classes of the general middle class category, as is evident from the listing of the chapters of Parts I and II of the book (see Table 15.4):

Table 15.4 Classification of the Indian Population

|

Part I |

|---|---|

I. |

The Merchant, the Artisan, and the Landed Aristocracy |

II. |

The Authoritarian Basis of Society |

|

Part II |

III. |

The Commercial Middle Class |

IV. |

The Industrial Middle Class |

V. |

The Landed Middle Class |

VI. |

The Educated Middle Class: 1. Main Objects of Western Education |

VII. |

The Educated Middle Class: 2. The Learned Professions |

Since these works are not strictly sociological, it is understandable that the authors chose to write generally on the emerging structures of social stratification, focusing more on the bulging middle class.