CHAPTER 8

Moment by Moment

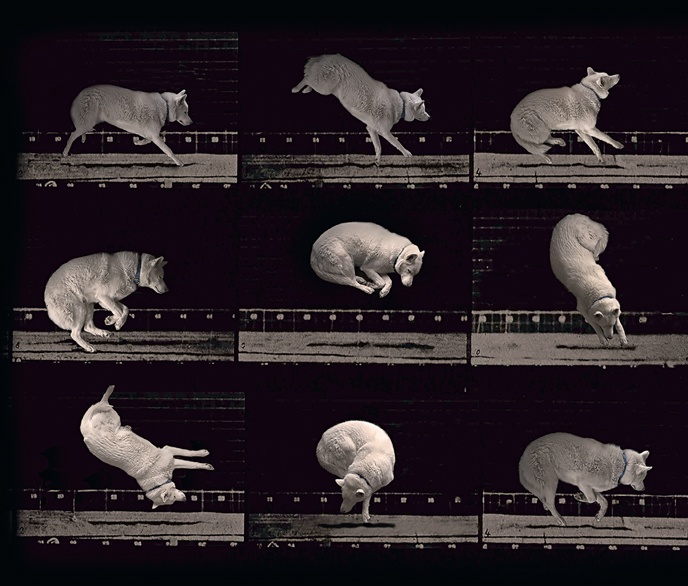

FIGURE 8.1 Lucy. © Andrea Jones

JONES MADE THIS WORK by adopting Eadweard Muybridge's famous grid representations of photographic studies of human and animal locomotion. Muybridge's stop-action images affirmatively settled the question of whether all four hooves of a horse in a gallop were simultaneously airborne. Up until that time, most painters depicted galloping horses with at least one hoof on the ground. These studies and the latter part of the nineteenth century secured photography's viability as an objective scientific means of recording and proving factual information.

What Are We Looking at?

Jones's choice of adopting this visual iconography of repeatable provable fact to document a sleeping dog and dying bug expands the context of both scientific and psychological endeavor. In so doing, she is arguably placing love and suffering within a quantifiable context as well as inviting a dialogue between the old enemies of fact versus conjecture and science versus spirituality.

How Can the Image Be Interpreted?

Lucy, the dog, appears to be asleep. We can make this assumption because her eyes are closed and she looks to be very relaxed and at rest. Sleep is still a state being researched and is not fully understood, but there is no doubt that we all need it to survive and thrive. Even more magical is dreaming. Have you ever woken up utterly elated, or utterly mad at someone because of how they behaved in your dreams? The brain appears to have difficulty in distinguishing between what has actually happened as opposed to what we experience while dreaming. It could also be argued that the brain has difficulty distinguishing between what has actually happened versus what we think or feel happened to us while being awake. Think about widely disparate eyewitness accounts of the same event.

There is great playfulness and maybe a little mischief in appropriating Muybridge's visual ledgers, designed to establish certainty, in order to do the opposite. Well, up to a point. There is certainty that the dog is asleep, although we can't begin to guess where her dreams are actually taking her. Rotating some of the images further erases scientific integrity, even of observation, and moves us further into the photographer's interpretation of her dog's adventures while tumbling through her imagined dreams. Just as some of the dog's saltos are impossible, the joy of the impossible is maybe the greatest dividend of dreams. How often is it not the possible but instead the impossible that sustains us? Daydreaming is maybe the best antidote to perceived reality. I suggest you use this element of imagination and bring it to your work (Figure 8.1).

What Are We Looking at?

While a nightmare technically describes an unpleasant dream, it would seem that most nightmares are experienced awake.

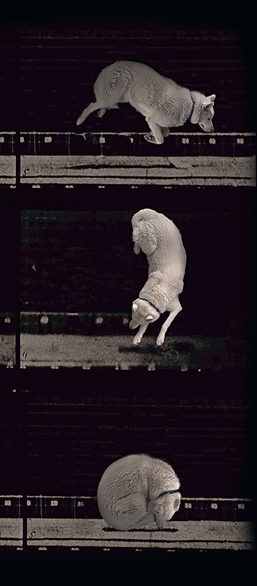

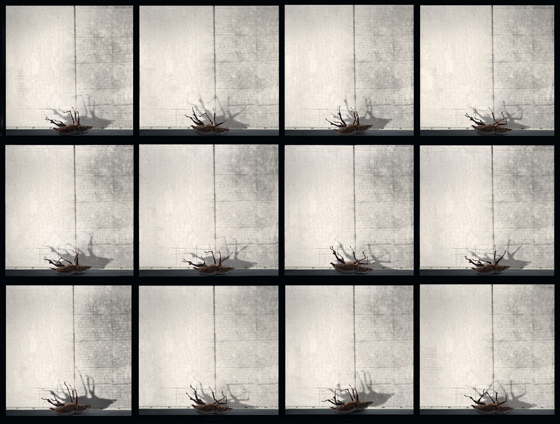

FIGURE 8.2

The image of the suffering beetle.

© Andrea Jones

Yes, we may be suffering in our dreams and experience relief when we finally wake or experience disappointment when true bliss turned out to be just a dream. But true suffering belongs to the fully conscious: the struggle of the dying beetle thus becomes a metaphor for battling both physical and emotional pain (Figure 8.2).

Maybe this little creature just needs a helpful gesture of a finger to turn it over and send it on its merry way. Is it the photographer's job to document or to help? This is an old question that can only be answered in the moment, requiring the full knowledge of the circumstances, and the judgment of the person who is wielding the camera.

How Can the Image Be Interpreted?

I rather suspect that we are looking at a dying beetle: an insect that probably had the misfortune of crossing an undetectable pest control barrier and whose body is now contracting and cramping within its protective exoskeleton that will soon become its tomb. Jones is making us look again and again at its desperate and futile gestures. The twelve frames now become charged in a different way. Given the short lifespan of most insects, is the suffering equivalent to twelve months of a human life? Is Jones alluding to the twelfth station of the cross and many of the other historic, holy, and magical associations the number holds? Whatever the significance of the number, all of us live by its recurrence, twice, each day, once each year, and generally when buying eggs.

If we have a closer look at each image, we can see that the beetle's spasms move it very slowly to the right; past the centrally placed line, the finish line, the line between life and death that each of us must cross one day.

Conclusion

When looking at time-lapse photography, time becomes an overt element. It informs each and every frame. The time taken to compose, to adjust depth of field or to adjust shutter speed is preset; and it constructs its own electromechanical rhythm. The preordained intervals may last for a small eternity for the beetle. However, although the time that elapses between a new encounter with another frame for the viewer may be inconsequential, the image, in its totality, may be resonating in ways that aren't confined to time. A new compassion may prevent the spraying of another poisoned border or the purchase of factory farmed eggs.

Please note. The beetle was already dead and Jones in no way made it suffer. She moved the legs in Photoshop, arguably another layer to using Muybridge's scientific methods, appropriated for emotional affect and provocation. What of all the images that have recorded the most cruel and nefarious experiments conducted in the world? Jones subtly reminds us of this too.

Assignments You May Want to Challenge Yourself With

•Reinterpret the canonized and iconized

•Empathy

•Compartmentalization

•Time-lapse