Chapter 11

Supply Chain Relationship Management

![]() LEARNING OBJECTIVES

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

- Explain the importance of relationships to SCM.

- Identify categories of supply chain relationships and their defining dimensions.

- Explain the differences between transactional-based and relational-based relationships.

- Describe the development and management of trust-based relationships.

- Explain different causes of conflict between supply chain members.

- Describe methods of dispute resolution and negotiation.

![]() Chapter Outline

Chapter Outline

- Supply Chain Relationships

Importance of Supply Chain Relationships

Relationship Dimensions

Scope

Criticality

Supply Chain Relationship Matrix

- The Role of Trust

Trust-Based Versus Power-Based Relationships

Developing Trust-Based Relationships

Assessing the Relationship

Identifying Operational Roles

Creating Effective Contracts

Designing Effective Conflict Resolution Mechanisms

Managing Trust-Based Relationships

Commitment

Clear Method of Communication

Performance Visibility

Fairness

- Managing Conflict and Dispute Resolution

Sources of Conflict

Dispute Resolution Procedures

Litigation

Arbitration

Mediation

Negotiation

- Negotiation Concepts, Styles, and Tactics

Leverage

“Position” versus “Interest”

Negotiator's Dilemma

Negotiation Styles

Adversarial Tactics

Problem-Solving Tactics

- Relationship Management in Practice

The Keiretsu Supplier-Partnering Model

Partnership Agreements

Diluting Power

- Chapter Highlights

- Key Terms

- Discussion Questions

- Case Study: Lucid v. Black Box

Verizon Wireless, Inc. is a wireless service provider that owns and operates the largest telecommunications network in the United States. Apple, Inc. is a multinational corporation that creates and markets personal computers and consumer electronics such as the iPhone multi-function cellular phone. Verizon made a name for itself for having a remarkably reliable network. Apple's iPhone revolutionized the cell phone market by including features that allow users to surf the Internet, send and receive photographs and videos, and download content. The two companies are members of the same supply chain.

A few years ago Verizon and Apple almost created a partnership. Verizon, a reputable wireless service provider, would supply the network for Apple's fancy new phone. However, the two companies failed to reach an agreement. Verizon feared relinquishing control over maintenance, retail and service fees pursuant to Apple's demands. Apple feared creating a mobile phone device for Verizon's network because it did not operate globally. Despite their telecommunications expertise, Apple and Verizon ceased communicating for two years. As a result, Apple went with a different service provider.

Then Apple began receiving complaints that the wireless service for its iPhone was slow, choppy, and unreliable, given the tremendous amount of data transmitted over the wireless networks by millions of users. As aresult of an overloaded service provider, many iPhone users suffered dropped calls. At the same time, Verizon was promising to develop an even faster global network. The CEO of Verizon Wireless reached out to the CEO of Apple to say, “We really ought to talk about how we do business together. We weren't able to [reach an agreement] a couple of years before, but it's probably worth having another discussion to make sure we're not missing something.” The CEO of Apple responded, “Yeah, you're probably right. We have missed something.”

With excitement swelling on the part of cell-phone users around the globe, Verizon and Apple had finally decided to work together. Utilizing Verizon's superb wireless service and Apple's highly-sought-after phone, the two companies decided to collaborate in order to produce something many have called the “dream phone” with superior service and capabilities.

The relationship between Verizon and Apple illustrates supply chain companies entering into a relationship to create value for the final customer. It also illustrates the importance of relationship building, importance of value provided by each party, and the role of negotiation in the process. Time will tell whether the “dream phone” is worthy of the name. But without attempting to communicate with one another, the “dream phone” would have remained just that: a dream.

Adapted from: Ellison, Sarah. “The Dream Phone.” Fortune. November 15, 2010: 128.

SUPPLY CHAIN RELATIONSHIPS

IMPORTANCE OF SUPPLY CHAIN RELATIONSHIPS

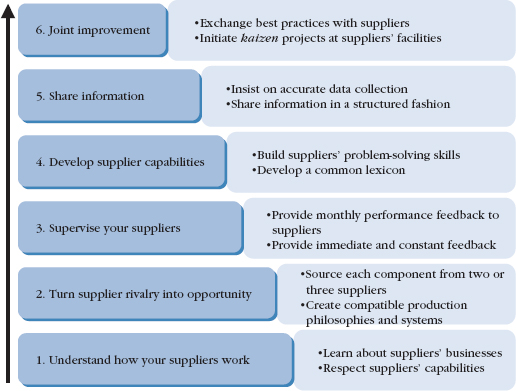

We have discussed the management and design of the physical network structure of the supply chain, the use of information technology to connect supply chain members, and the management of numerous processes across enterprises. In this chapter we discuss one of the most important aspects of supply chain management (SCM)—the management of relationships between supply chain members. In essence this involves the management of “people.” Management of people overlays the physical supply chain structure and the connecting information technology, as shown in Figure 11.1.

Recall that SCM involves coordination of activities, collaboration in planning, and sharing of information among members of the supply chain so that they jointly plan, operate, and execute business decisions. Notice that engaging in these activities relies on relationships between members of the supply chain. In fact, relationship management is probably the most important aspect of SCM. It affects all areas of the supply chain and can have a dramatic impact on performance. Supply chain activities can be highly successful if there is trust and commitment between companies to work together. However, even if all the structural elements of the supply chain are in place—information technology, facilities, distribution centers, transportation management systems, and inventory systems—SCM efforts can fail as a result of sabotage, mistrust, or just poor communication. Information technology only provides the capability for information sharing. It is supply chain relationships that make it happen.

FIGURE 11.1 Relationship management as an element of SCM.

Managing supply chain relationships involves managing relationships between people. It involves issues that include respect, trust, agreements, negotiation, joint ventures, contracting, and even conflict resolution. Therefore, supply chain management is primarily about the management of relationships across complex networks of companies. As a result, developing and managing relationships between supply chain partners may be the most important element of successful SCM.

RELATIONSHIP DIMENSIONS

Not all supply chain relationships need to be, or should be, treated the same. Most companies today have hundreds or even thousands of suppliers. Some provide tangible goods, such as component parts or raw materials, while others provide services, such as transportation and logistics. All these relationships are not all of equal importance. Relationship management requires time and effort, and should not be wasted on relationships that are transactional in nature. As we will see, supply chain relationships should be carefully segmented based on how much management is needed.

Consider that even a small bakery can have dozens of suppliers—from common items such as sugar and flour, to specialty items such as hazelnut paste or truffle oil. Some suppliers provide commodity items or services where cost is the determining criteria. For example, companies have historically used suppliers for certain routine activities, such as package deliveries, records management, or uniform cleaning. These routine services are transactional in nature and do not require relationship management. On the other hand, some companies use supply chain partners for almost all activities. This may include outsourcing virtually everything, including manufacturing, distribution, R&D, innovation, and even strategic planning. For example, Nike is a company that focuses on marketing and innovation, and outsources manufacturing and distribution to other members of its supply chain. Similarly, Apple focuses on product innovation and marketing, and outsources all manufacturing to Foxcon, a Chinese manufacturer. In these cases, careful and ongoing relationship management is critical.

There are two dimensions that help differentiate supply chain relationships. The first is scope, or degree of responsibility, assigned to the supplier. A greater scope means a greater dependence on the supplier. The second dimension is criticality of sourced item or task. Criticality is the extent to which the sourced item or task impacts the ability of the organization to perform its core competencies. The greater the criticality of the sourced item the greater the consequences of poor performance to the company and the greater the requirement for relationship management. Let's look at these dimensions in a bit more detail.

Scope. At one extreme the relationship can be narrow in scope where a supplier provides a limited amount of items or provides one task from many possible tasks that make up an entire function. For example, this may be a supplier that is responsible for the replenishment of only maintenance, repair and operating items (MRO) inventories (maintenance, repair, and operating items, discussed in Chapter 9). At another extreme the scope can be broad, where the bulk of items or services are provided by one supplier. An example would be complete manufacturing, as provided by Foxcon for Apple and Sony. Another example would be the comprehensive outsourcing of all aspects of the logistics function to a third-party logistics (3PL) provider, such as provided by UPS.

When the responsibility is relatively small, confined, and specific—such as handling a buyer's returned inventories, arranging for item disposal or restocking, or providing a commodity item such as sugar in the bakery—the risks of such a relationship are small. Such confined relationships are good for standardized products or repeatable tasks that are easily defined, and have a limited choice of options.

As the scope of the relationship become more comprehensive, however, the degree of customization provided by the supplier progressively increases, as does the risk to the buyer. For example, this might be using a supplier to manage all inventories, including order management, or the complete management of a company's transportation system. The supplier may now be responsible for all aspects of the function, including equipment, facilities, staffing, software, implementation, management, and ongoing improvement. This is the level of outsourcing often seen with the services provided by third-party logistics (3PL) providers.

A large scope of tasks provided by a supply chain partner can bring large benefits as it allows the company to focus on their core competencies. The risks, however, can also be great as both operational and strategic responsibility is now in the hands of an outside party, requiring close relationship management.

Criticality. The second differentiating dimension of supply chain relationships is the criticality of the tasks provided by a supplier. At one extreme a supplier can provide commodity items, such as sugar in the bakery example, or a more tactical task, such as records management. At the other extreme, a supplier may provide—and be the only source of—a critical component. Similarly, a firm may just outsource transportation, or it may outsource all aspects of the logistics function, such as the design, implementation, and ongoing management.

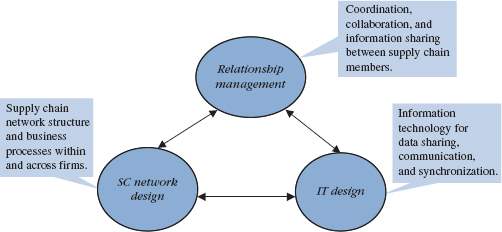

The higher the criticality of the outsourced task the greater the business risk to the buyer. As a result, this directly impacts the degree of relationship management required and the nature of the buyer-supplier relationship. When tasks with low criticality are outsourced the relationship between buyer and supplier is primarily contractual. Relationship management is primarily focused on the transactional nature of the outsourced function. As criticality increases, the relationship moves from being contractual to becoming more relational. When there is low criticality, the supplier has responsibility over non-strategic items or tasks. The relationship is contractual and the buying firm continues to have operational and managerial responsibility over all internal functions and process. As the suppliers role becomes more comprehensive, however, the supplier increasingly becomes responsible for managerial and possibly the strategic aspects of the function. This moves the relationship from more transactional to more relational as shown in Figure 11.2.

FIGURE 11.2 Nature of supply chain relationships.

SUPPLY CHAIN RELATIONSHIP MATRIX

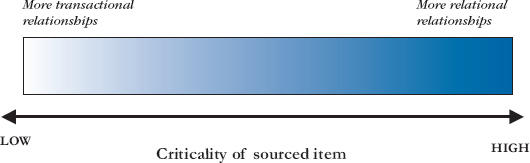

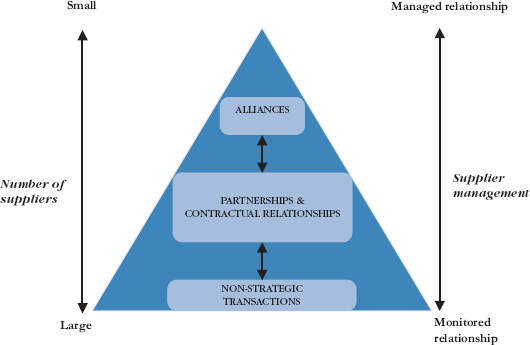

To understand categories of supply chain relationships we need to consider both dimensions—scope and criticality. Together these dimensions create four categories of buyer-supplier relationships that differ in the level of relationship management required. For example, a large scope coupled with high criticality leads to more comprehensive buyer-supplier relationships and to different types of managerial requirements than are necessitated by smaller scope and lower criticality. There are four categories of relationships are: non-strategic transactions, contractual relationships, partnerships, and alliances, and are shown in Figure 11.3.

- Non-Strategic Transactions. When both scope and criticality are low we have relationships that are solely transaction oriented, such as a simple commodity exchange. The product provided by the supplier is typically standardized and alternative sources of supply or market access are readily available. There is little mutual dependence on which to base a relationship and there is limited communication between supplier and buyer. Indeed, there is little reason for a relationship to evolve, and an arms-length approach dominates the communication. From an organizational standpoint, non- strategic relationships may form simply because there is no need for close interactions. The sourced items are typically standardized and their low criticality does not necessitate close relationship management. The relationship, however, may evolve into a more encompassing relationship if the scope increases over time and involves multiple transactions. In that case it might become a contractual relationship.

- Contractual Relationships. Contractual relationships occur when the scope is high, although the criticality of purchased items or tasks is low. This relationship is characterized by moderate levels of communication frequency, as there is a greater need for control over supplier activities. From an organizational standpoint, there is an awareness of the need for some management of the relationship due to sheer size of the arrangement. Also, there is a higher level of trust and greater levels of interaction than in non-strategic relationships. However, there is no desire to raise the commitment to a more personal relationship due to low criticality. The relationship is strictly based on formal contracts reducing the need for communication between boundary-spanning personnel.

- Partnerships. This relationship type is characterized by the sourcing of critical components or tasks, albeit low in scope. The term “partnership” is used to connote strong and enduring trust between supplier and buyer, as well as a strong commitment to the relationship although the parties may not interact frequently. An example of this relationship could be the sourcing of just-in-time (JIT) replenishments of a critical manufacturing component. Due to the high criticality, the supplier has greater commitment to the relationship. However, given the higher level of trust and relatively small scope, there is limited frequency of interaction. The management of the relationship is not extensive and the buyer may entrust the supplier with greater control.

- Alliances. The most comprehensive buyer-supplier relationships occur when both criticality and scope are high. These arrangements are defined as alliance relationships, and reflect high interaction frequency, significant trust and commitment between supply chain partners. Alliances presume a high level of confidence in the capabilities and integrity of the other party, and require significant resource investment in ongoing relationship management. In alliances, vendor products and services are highly customized and evolve with the business needs of the client. There is also great potential for flexibility given the typically large transaction volumes. In some cases these alliances may even be legalized through incorporation. A case in point is an alliance between Texas Utilities and CapGemini, called CapGemini Energy for the purpose of outsourcing its entire information management organization.

These different buyer-supplier relationships have different managerial requirements. More comprehensive relationships, such as alliances, have a greater requirement to manage the relationship. By contrast, less comprehensive relationships, as exemplified by non-strategic transactions and contractual, primarily require performance monitoring. This is shown in Figure 11.4. Therefore, the number of comprehensive outsourcing engagements, such as alliance type relationships, must be kept small due to the extensive relationship management requirement. Relationships such as non-strategic transactions, on the other hand, can be numerous as only monitoring efforts are required.

FIGURE 11.4 Managing supply chain relationships.

Proctor & Gamble

Open innovation and strategic licensing are two developments in the business world that show the benefits of supply chain relationships, even with competitors. Open innovation means that, instead of relying exclusively on ideas created by intensive internal R&D efforts, organizations are willing to bring externally generated ideas to market. Strategic licensing means that, instead of guarding internally developed intellectual property jealously, companies are willing to license these innovations to outside companies.

Proctor & Gamble (P&G) is a leading consumer-product developer that created many of its leading brands through costly scientific internal research. That is, until P&G adopted an alternative innovation strategy that seeks to obtain half of its product innovations from external sources. The highly popular SpinBrush marketed by P&G was actually invented by four outside entrepreneurs rather than from P&G's own laboratories. Open innovation can save money by reducing reliance on cost-intensive in-house scientific research.

P&G also implemented a strategic licensing policy that offers internally generated ideas to outside companies, including competitors, if P&G fails to utilize the idea themselves after three years. Strategic licensing can create value by preventing ideas from languishing internally. This approach, gaining popularity with Fortune 500 companies, signals a retreat from the idea of “exclusivity value,” where a company maintains prominence simply by hindering its competitors.

P&G's patented “reliability engineering,” which originally gave the company a competitive edge by reducing waste and production time in assembly-line manufacturing, is now for sale. Instead of keeping core technology assets a secret, P&G's approach is to strategically license these technologies to anyone willing to pay the right price—including competitors.

Adapted from: Chesbrough, Henry W., “The Era of Open Innovation,” and Kline, David, “Sharing the Corporate Crown Jewels.” MIT Sloan Management Review, Spring 2003.

THE ROLE OF TRUST

TRUST-BASED VERSUS POWER-BASED RELATIONSHIPS

An important characteristic of competitive supply chains is the focus on relationship building and the move away from arms-length adversarial relationships that had been dominant in the past. Underlying this idea is that the buyer-supplier relationship should be based upon a partnership of trust, commitment, and fairness. There are numerous advantages to such relationships that can be long-term and mutually beneficial. The competitive advantage of companies such as Toyota and Honda over their competitors in the auto industry comes from the collaborative relationships they have developed with their suppliers. Successful supply chains will be those that are governed by a constant search for win-win relationships based upon mutuality and trust.

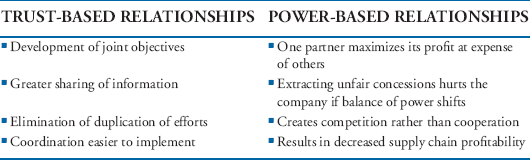

A trust-based relationship between supply chain partners helps improve performance for the following reasons. First, a cooperative relationship results in the development and sharing of joint objectives. This means that each party is much more likely to consider the other party's objectives when making their decisions. Second, managerial strategies to achieve coordination become easier to implement. Sharing of information is easier between parties that trust each other. Also, it is easier to implement and design operational improvements as both parties are aiming for a common goal. Third, cooperation and coordination result in the elimination of duplication of efforts between parties. Consequently, supply chain productivity is increased. An example may be that the manufacturing firm does not have to inspect the quality of materials it receives from its supplier. Finally, greater sharing of sales and production information results in enabling members of the supply chain to coordinate production and distribution decisions.

Historically, supply chain relationships have been based on power. In a power-based relationship, the stronger party dictates its view. Although exploiting power may be advantageous in the short term, its negative consequences are felt in the long term for three main reasons. First, exploiting power results in one supply chain partner maximizing its profits, often at the expense of other partners. This decreases total supply chain profits. Second, exploiting power to extract unfair concessions can hurt a company once the balance of power changes. Third, when a member of a supply chain systematically exploits its power advantage, the other members find ways to resist. For example, when retailers tried to exploit their power, manufacturers have sought ways to directly access the consumer. This included selling over the Internet and setting up company stores. The result can be a decrease in supply chain profits because different members are now competing rather than cooperating. Figure 11.5 highlights the differences between trust and power based relationships.

FIGURE 11.5 Characteristics of trust-based versus power-based relationships.

Given the negative consequences of power-based relationships, cooperation and trust between supply chain members is highly valuable. However, these qualities are very hard to initiate and sustain. There are two views on how cooperation and trust can be brought into any supply chain relationship:

- Contractual-Based View. This view states that formal contracts should be used to ensure cooperation among supply chain members. With a contract in place, parties are assumed to behave in a trusting manner for reasons of self-interest, although actual trust has not been built.

- Relationship-Based View. Trust and cooperation are viewed as a result of a series of interactions between the partners built over time. Positive interactions strengthen the belief in the cooperation of the other party.

In practice, neither view holds exclusively. Initially in the relationship the contractual-based view holds. Over time, however, the relationship evolves toward a relationship-based view, if it is a strong supply chain relationship. A contract is always the basis of a business partnership. Parties that may not trust each other yet have to rely on the building of trust to resolve issues that are not included in the contract. Conversely, parties that trust each other and have a long relationship still rely on contracts. In most effective partnerships, a combination of the two approaches is used. An example of this situation is when suppliers sign an initial contract with manufacturers containing contingencies, yet they never refer to the contract afterward. Their hope is that all contingencies can be resolved through negotiation in a way that is best for all parties.

These are two phases to any long-term supply chain relationship. First is the design phase of the relationship where ground rules are established and the relationship is initiated. Second is the management phase where the interactions based on the ground rules are managed. A manager seeking to build a supply chain relationship must consider how cooperation and trust can be encouraged during both phases of the relationships. Careful consideration is very important because in most supply chains, power tends to be concentrated in relatively few hands. The concentration of power often leads managers to ignore the effort required to build trust and cooperation, hurting supply chain performance in the long term. Next we discuss how supply chain relationships can be designed to encourage cooperation and trust.

DEVELOPING A TRUST-BASED RELATIONSHIP

A trust-based relationship between two companies in the supply chain creates a sense that each company can depend on the other and has confidence in joint decisions. Trust creates the belief that each company is interested in the other's welfare and would not take action without considering the impact of those decisions on other companies as well, in addition to themselves. However, building a trust-based relationship can be difficult as it requires changing the nature of traditional relationships between suppliers and customers in the supply chain. There are certain key steps that can be followed in designing trust-based relationships. We look at these next.

Assessing the Relationship. The first step in designing a supply chain relationship is to clearly identify the mutual benefit that the relationship provides. In most supply chains, each member of the partnership brings distinct skills, all of which are needed to supply a customer order. For example, a manufacturer produces the product, a carrier transports it between firms, and a retailer makes the product available to the final customer. The contribution of each party to supply chain success and profitability must be made clear.

An important element of the relationship is equity. Fair dealing in the relationship—called equity—should be an important element when developing a relationship. Equity measures the fairness of the division of the total profits between the parties involved. Members of the supply chain are unlikely to participate in true coordination unless they are confident that the resulting increase in profits will be shared equitably. For example, when suppliers make an effort to reduce replenishment lead times the supply chain benefits because of reduced safety stock inventories at manufacturers and retailers. Suppliers are unlikely to put in the effort if the manufacturers and retailers are not willing to share the increase in profitability with them. Consequently, a supply chain relationship is likely to be sustainable only if it increases profitability and this increase is shared equitably between the parties.

Identifying Operational Roles. When identifying operational roles and rights of each party in a supply chain relationship, managers must consider the interdependence between the parties. One source of conflict occurs when the tasks are divided in a way that makes one party more dependent on the other. In fact, dependence of one party on another often leads to frustration among supply chain firms. In many partnerships, an inefficient allocation of tasks results simply because neither party is willing to give the other a perceived upper hand based on the tasks assigned.

Traditionally, supply chain activities have been sequential, with one stage completing all its tasks and then handing them off to the next stage. This was called sequential interdependence, where the activities and information of one partner preceded the other. A different relationship is reciprocal interdependence, where parties come together and exchange information, with information flowing in both directions. Such a relationship is the one between P&G and Wal-Mart, where the companies have created reciprocal interdependence. An example of this is their use of Collaborative Planning and Forecasting for Replenishment (CPFR), discussed in Chapter 8. The process relies on ongoing work teams with members from both Wal-Mart and P&G. Wal-Mart brings demand information to the process, as it is closest to the customer, and P&G brings information on available capacity. The teams then decide on the production and replenishment policy that is best for the supply chain.

Reciprocal interdependence requires a significant effort to manage and can increase transaction costs if it is not managed properly. However, reciprocal interdependence is more likely to result in supply chain profitability because all decisions take the objectives of both parties into account. Reciprocal interdependence increases the interactions between the two parties, increasing the likelihood of trust and cooperation if positive interactions occur. Reciprocal interdependence also makes it harder for one party to be opportunistic and take self-serving actions that hurt the other party. Therefore, greater reciprocal interdependence in decision making increases the chances of an effective relationship.

Creating Effective Contracts. Managers can help promote trust by creating contracts that encourage negotiation as unplanned events arise. Contracts are most effective when all future contingencies can be accounted for. Unfortunately, practical realities of the business environment make it impossible to design a contract that includes provisions for all contingencies. Therefore, it is essential that the parties develop a relationship that allows trust to compensate for gaps in the contract. The relationship often develops between appropriate individuals that have been assigned from each side. Over time, the informal understandings and commitments between the individuals tend to be formalized when new contracts are drawn up. When designing the partnership and initial contract, it should be understood that informal understandings will operate side by side and these will contribute to the development of the formal contract over time. Thus, contracts that evolve over time are likely to be much more effective than contracts that are completely defined at the beginning of the partnership.

Over the long term, contracts can only play a partial role in maintaining supply chain partnerships. What is needed is a combination of a contract, the mutual benefit of the relationship, along with trust that compensates for gaps in the contract.

Designing Effective Conflict Resolution Mechanisms. Effective conflict resolution mechanisms can strengthen supply chain relationships. Conflicts will inevitably arise. Unsatisfactory resolutions cause the partnership to worsen, whereas satisfactory resolutions strengthen the partnership. A good conflict resolution mechanism should give the parties an opportunity to communicate and work through their differences. An initial formal specification of rules and guidelines for financial procedures and technological transactions can help build trust between partners. The specification of rules and guidelines facilitates the sharing of information among the partners in the supply chain.

Regular and frequent meetings between members of both organizations facilitate communication and are an important part of conflict management. These meetings allow issues to be raised and discussed before they turn into major conflicts. They also provide a basis for resolution at a higher level, should resolution at a lower level not take place. An important goal of these formal conflict resolution mechanisms is to ensure that disputes over financial or technological issues do not turn into interpersonal squabbles.

MANAGING A TRUST-BASED RELATIONSHIP

Once a trust-based relationship is developed, it must be managed. Effectively managed supply chain relationships promote cooperation and trust, increasing supply chain coordination. In contrast, poorly managed relationships lead to each party being opportunistic, resulting in inefficiency and loss of profitability. One problem, however, is that management of the relationship is often seen by managers as a routine task with little reward. Often top management prefers to be involved in the design of a new partnership that often provides corporate visibility, but is rarely involved in its management. This has led to a mixed record in running successful supply chain alliances and partnerships. The following factors are a part of managing a successful supply relationship.

Commitment. Commitment of both parties helps a supply chain relationship succeed; in particular, commitment of top management on both sides is crucial for success. The manager directly responsible for the partnership can also facilitate the development of the relationship by clearly identifying the value of the partnership for each party in terms of their own expectations.

Clear Method of Communication. Having clear organizational arrangements in place significantly increases the chances of relationship success. This is especially important when it comes to information sharing and conflict resolution. Lack of information sharing and the inability to resolve conflicts are the two major factors that lead to the breakdown of supply chain partnerships.

Performance Visibility. Mechanisms that make the actions of each party and resulting outcomes visible help avoid conflicts and resolve disputes. Such mechanisms make it harder for either party to be opportunistic and help identify defective processes, increasing the value of the relationship for both parties.

Fairness. The more fairly the stronger partner treats the weaker, vulnerable partner, the stronger the supply chain relationship tends to be. The issue of fairness is extremely important in the supply chain context because most relationships will involve parties with unequal power.

Coca-Cola in Africa

The Coca-Cola Company is a beverage manufacturer, marketer and retailer most famous for the sweet, brown, fizzy soda known by almost everyone as “Coke.” The red and white Coca-Cola circle may be one of the most recognizable brands the world over. The company recently sponsored the 2010 FIFA World Cup hosted in South Africa. Coke's presence in Africa dates back to 1929, but Africa has taken on a new role in the eyes of this major corporation.

Growth has slowed down significantly for Coca-Cola products in Europe and the United States, so the company hopes to establish its product in Africa to ride the wave of Africa's projected economic growth. Many experts predict Africa will grow in the next few decades much as India and China did in the last few decades. Currently, Coke is the African continent's largest employer, with business units in every African country, 160 manufacturing plants, and 65,000 employees.

Coke has chosen to partner with small shop owners in alleyways in small villages. The business model needed to partner with these retailers is unique. Coca-Cola provides the refrigerators, and even paints the storefronts with the brand logo. Rather than using delivery trucks to restock the retail stores, Coca-Cola ships cases of bottles from bottling plants to one of 3,000 Manual Distribution Centers. Here, young men and women load the cases onto a trolley and deliver drinks by hand. This distribution model is apt for a region with relatively poor transportation infrastructure. Further, given little room for extra inventory, many store owners order just one case per day, which would render truck deliveries an overkill.

In return for helping establish the Coca-Cola brand throughout Africa, Coca-Cola educates its microdistributors in ways including how to save resources by timing the icing of the bottles for lunch rush, and how to purchase real estate with the extra revenue earned by selling Coke. It is an example that win-win partnerships can occur despite differences in power or size.

Adapted from: Stanford, Duane D. “Coke's Last Round.” Bloomberg Businessweek, November 1, 2010: 54.

Unanticipated situations that hurt one party more than the other often arise. The more powerful party often has greater control over how the resolution occurs. The fairness of the resolution influences the strength of the relationship in the future. Fairness requires that the benefits and costs of the relationship be shared between the two parties in a way that makes both winners.

MANAGING CONFLICT AND DISPUTE RESOLUTION

As we have seen, there are many types of supply chain relationships that serve many purposes. Even when there is trust and fairness, conflict can arise. In this section we look at sources of conflict and procedures for dispute resolution.

SOURCES OF CONFLICT

One of the most problematic issues in relationship management is how to manage conflict. In order to ward off conflict before they turn into disputes, we should understand the sources of conflict. There are five potential sources of conflict that may arise in supply chain relationships: relationship conflict, data conflict, interest conflict, structure conflict, and values conflict.1

Relationship conflicts are a result of strong emotions, misperceptions or stereotypes, poor communication or miscommunication, and repetitive negative behavior. In inter-cultural communications, stereotypes are especially problematic. We attribute negative features to people or institutions we don't recognize or understand. When different languages are involved—as in multicultural negotiation—the risks of miscommunication increase.

Data conflicts are caused by lack of information, misinformation, different views on what is relevant, different interpretation of data, and different data-assessment procedures. Information traveling between multiple supply chain members can be lost just as in the children's game of telephone. Even when all relevant parties have the same spreadsheet before them, with the same data, differences in how the data is interpreted can cause conflicts.

Interest conflict can be caused by perceived or actual competition over substantive interest. An example might be the selected criteria used to determine whether a supplier meets a certain quality standard. Interest conflict can also arise from competition over procedural interests, such as a protocol for processing orders. It can also arise over psychological interests, such as how blame or praise is to be allocated. In supply chain management, for example, not equally sharing cost savings between members that result from process improvements can create interest conflict.

Structural conflicts are caused by factors such as destructive patterns of behavior or interaction, unequal control, ownership, or distribution of resources, unequal power or authority, geographical, physical, or environmental factors that hinder cooperation, and time constraints. Structural conflicts are among the most prominent sources of conflict in supply chain management relationships.

Value conflicts are caused by different criteria for evaluating ideas or behavior; mutually-exclusive intrinsically valuable goals; and different ways of life, ideology, or religion. Value conflicts are to be expected in inter-cultural interactions. For example, western companies operating in India have found it difficult to engage older workers in a participatory style of management where hierarchical roles are the cultural norm.

DISPUTE RESOLUTION PROCEDURES

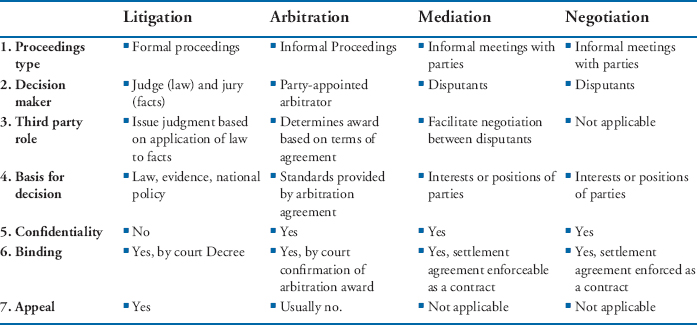

Figure 11.6 illustrates the four primary dispute resolution processes. To be sure, there are hybrids that involve combinations of these procedures.

From left to right, the procedures transition from formal and adjudicative (where an independent party determines the outcome of the dispute) to informal and consensual (where the disputants themselves determine the outcome of the dispute). Also, the nature of third-party intervention is different, with litigation involving decisional assistance by a judge, and mediation involving procedural assistance by a mediator. Supply chain partners should decide ahead of time how they will resolve disputes, which will inevitably arise, considering the features unique to each dispute resolution procedure. Figure 11.7 shows differences in dispute resolution procedures.

![]()

FIGURE 11.6 Dispute resolution procedures.

FIGURE 11.7 Differences in dispute resolution procedures.2

LITIGATION

When a supply chain member breaches a contract, or commits fraud, a legal wrong has been committed. This may be stealing inventory or using lesser grade materials than contracted. Consider the case of Mattel Toys from a few years ago that found its Chinese suppliers were using lead in their materials. The victim may choose to file a lawsuit in order to be made whole. Alegal sanction should deter the wrongdoer from repeating such behavior. However, some companies will factor litigation costs into the overall costs of doing business, and will only avoid breaching a contract when the costs exceed the benefits. Litigation costs can be excessive. They involve lawyer fees, court fees, producing sensitive data for evidence, depositions of responsible parties (which can impede productivity), the uncertainty of a jury verdict, and the potential for bad press (because lawsuits are usually public). Time-consuming, uncertain and costly, litigation is viewed by some as the “nuclear option”: it should be used only as a last resort. Litigation is viewed by some as a management failure, because resolution of the dispute is no longer within the management's control. Rather, factual controversies are resolved by a jury, and questions of rights and obligations are determined by an independent judge. While trial court opinions can be appealed, the process is usually protracted and costly. Litigated outcomes are usually “all or nothing” for either the plaintiff or the defendant.

ARBITRATION

When both parties can agree to procedures and norms for how their disputes should be resolved, they can create an arbitration agreement that stipulates how an arbitrator will be selected and which controversies will be subject to arbitration. This option is especially useful in international commercial contexts, where suing in the courts of another nation may not be desirable to either party. Further, arbitration may be desirable for businesses that specialize in highly technical fields who want to avoid having factual questions decided by a lay jury. Instead, the parties can choose a neutral arbitrator who is an expert in their field to determine the outcome. The parties can also stipulate by agreement that certain issues will be arbitrated while other matters may be litigated. Arbitration allows the parties to customize the dispute resolution procedure. In fact, they may agree that the law is irrelevant and industry norms or customs should govern the outcome. Like litigation, arbitration involves a neutral third-party who issues a binding decision. Unlike litigation, however, arbitrators are not obligated to provide a reasoned opinion for their award. The choice to arbitrate a dispute should bemade with care, because courts usually enforce arbitration agreements, requiring parties to arbitrate disputes when they have agreed to in contract. Further, the choice of arbitrator must be made with care, because arbitration awards are almost never subject to review. Instead, they are enforced as mandatory and binding.

MEDIATION

Like litigation and arbitration, mediation relies upon a neutral third party. Unlike the former two procedures, the mediator does not have power to compel the disputants to accept any particular outcome. Mediators are more like facilitators than decision makers. The mediator acts as a “go-between” or conducts shuttle diplomacy, ferrying information, offers and counter-offers between the disputants. While some courts require the parties to attempt mediating their dispute before litigating, mediation is usually voluntary, and is the dispute resolution procedure of choice when preserving the relationship between the parties is more important than seeking vindication. In supply chain management, where long-term relationships are important, this is a much preferred method of dispute resolution than litigation and arbitration.

The structure of mediation and the issues that are subject to mediation are determined by the parties. The mediator must be impartial, creative, and patient. Mediators often help the parties devise creative solutions to their problems, but whether to agree to a mediated outcome is up to either party. In other words, mediation is a facilitated negotiation. The effectiveness of mediation depends not only on the attitude of the disputants, but also on the talent and style of the mediator.

NEGOTIATION

Negotiation is basically the process of gaining concessions from another party. Negotiation is the most informal of dispute resolution procedures and does not involve third-party assistance. The disputants agree to discuss or argue about a problem until they determine a resolution. Sometimes, parties will refuse to negotiate, and the only way to resolve the dispute is through a more formal mechanism. Sometimes, a party will agree to negotiate, but will do so with such aggressive tactics that the initiating party is better off not negotiating. Usually, powerful or sophisticated parties do better in negotiations than weak or unsophisticated parties. Negotiated decisions can be enforced as a contract. Negotiations can be viewed as adversarial, where each party tries to extract as much value out of the other as possible. Or, negotiations be viewed as problem-solving opportunities, where each party helps brainstorm the conflict to determine whether mutually beneficial agreements are possible. In supply chain relationship management, negotiations should consider more collaborative, problem-solving orientations toward dispute resolution. Because negotiation is consensual and does not require third-party intervention, it can be the most inexpensive and swift method for resolving disputes.

Commodity Swapping

Who says competitors can't be good to one another? One non-obvious way to lower the overall cost of supply chain operations is for competing companies to make a deal with each other to rationalize commodity sourcing. Swapping with a competitor may lead to mutual cost-savings where everyone “wins.”

Raw materials are traditionally shipped from the point of extraction to the point of processing. This takes place across vast oceans or continents. The innovation of commodity swapping allows some companies in iron, steel, chemicals, paper, oil, electricity and textile industries to virtually eliminate the cost of transporting commodities. When a shipment of metal bolts makes its way across the ocean, and passes another shipment of nearly identical bolts heading in the opposite direction, the managers receiving these shipments should consider swapping commodities with one another.

Consider the case of the Dow Chemical Company, which makes 100% of its polymers in the United States. Dow Chemical used to ship these polymers to be consumed by its own plants around the world, less than half of which were located in the United States. A competitor company, Arkema, with manufacturing based in France and Italy, made the same polymers, and shipped them around the world to be consumed internally, some by plants in North America. Both the European Union and the United States imposed import duties, and the Atlantic Ocean freight cost per metric ton was $40 to $60. The competitors saw an opportunity to engage in a cost-saving collaboration. After testing the competitor's product, Dow Chemical and Arkema negotiated a commodity swap to supply one another's polymer plants. This collaborative negotiation between competitors resulted in annual cost savings of tens of millions of dollars.

Swapping allows both parties to eliminate inefficient transport procedures. Commodity swapping is particularly useful when dealing with import taxes, large distances, and bulk quantities. The concept of swapping commodities can be extended to products as well as to manufacturing capacities. Benefits of swapping include reduced transport costs including import and export levies, reduced logistics costs including storage, reduced uncertainty in supply, reduced price volatility, reduced inventory, and reduced environmental impact.

Adapted from: Kosansky, Alan, and Ted Schaefer. “Should You Swap Commodities with Your Competitors?” CSCMP's Supply Chain Quarterly. Quarter 2, 2010.

NEGOTIATION CONCEPTS, STYLES AND TACTICS

We negotiate, consciously or not, every day. When you decide who will drive in the carpool, when you trade baseball cards, when you and your date decide where to go to dinner, you are negotiating. Negotiations involve give-and-take, a dance of sorts, where positions are exchanged until the two parties can agree to amutually beneficial settlement—that is, an agreement that satisfies the underlying interest of the parties. In the context of SCM, negotiations are required to determine the terms of the contractual relationship between business units in a supply chain.

Negotiations can take place concerning almost anything. Issues such as cost, quantity, quality, timing, control, options, shared resources and penalties for non-compliance are usually subject to negotiation. This section introduces you to negotiation concepts, styles and tactics that are of great use to managing supply chain relationships.

LEVERAGE

Leverage is one of the most important elements in a negotiation. The party with the most leverage is the one who loses the least from walking away from the negotiation table. The leverage one possesses strongly affects one's relative bargaining power in a negotiation. The party with greater leverage is able to extract the most value out of the counterparty. To illustrate, suppose you own the only Model-T Ford, which a notorious collector doesn't already possess. You are perfectly happy maintaining ownership of the car, because you believe on good evidence that its value will continue to appreciate. However, you do have bills to pay and the car isn't doing you much financial good sitting in your garage. This collector has an extremely ardent desire to possess this one remaining car so that he may complete his collection. He is, some would say, a fanatic about your Model-T. You have several outstanding offers for the car, though his is the highest bid. Because each of you has something the other wants—you have the product, he has the cash—you are in a position to negotiate. However, because you have less to lose from walking away from the negotiation, you have the most leverage. That is, you can choose not to negotiate with the collector because you have alternative bidders. The collector, however, has no choice but to negotiate with you because you possess the only remaining car. You can use this leverage to request a higher price for the car from the collector, regardless of what the other competing bids are. Before entering into a negotiation, you should reflect on who has the most leverage.

“POSITION” VERSUS “INTEREST”

Suppose you are a widget wholesaler, and you are in a negotiation with a retailer who might purchase your widgets. A position is what you signal to the counterparty about your willingness to accept or willingness to pay. When you say, “I won't accept anything less than $10.00 per unit,” and the retailer responds with, “I won't pay anything more than $7.00 per unit,” you are both stating a position. After this initial exchange of positions, you find yourselves at an impasse. You have both stated mutually exclusive positions and it looks like there is no way forward unless one of you changes your position.

An interest is the underlying reason for your position. Often, negotiators will conceal their underlying interests because they do not trust each other. This is common in arms-length negotiations. However, if both wholesaler and retailer in this example were to disclose their underlying interests to one another, they could discover possibilities for mutual gains. Perhaps you believe the retailer is only going to purchase a few widgets, and you need to charge a premium for such a small shipment. Your interest is in making a large enough profit from the deal to make processing the order worth your time. The retailer, on the other hand, has an interest in being the only vendor who supplies your brand of widget, but is afraid to mention this because she believes you may use it as leverage against her. If the two of you were to share your underlying interests, several possibilities would emerge. The wholesaler would realize the retailer was not a one-time buyer, and would stop treating her as such. The retailer would realize the wholesaler was not fixed at $10.00 per unit, but was offering that price because of a misperception. The retailer may offer to make repeat widget purchases if the wholesaler would offer a lower price per unit. By revealing underlying interests, negotiators are able to find a zone of mutually beneficial agreement.

NEGOTIATOR'S DILEMMA

When a negotiator shares truthful information, they have a higher chance of achieving mutually beneficial outcomes. Integrative opportunities are negotiation opportunities that are non-zero-sum. Here both parties can be made better off without making either party worse off. However, deception confers distributive advantages where one of the parties benefits more than the other. Distributive opportunities, on the other hand, are zero-sum negotiation opportunities. This is where what is good for one party is directly adverse to the other party.

Should you share truthful information about your underlying interests? Or should you conceal this information carefully? The negotiator's dilemma is the inevitable paradox at the core of negotiation. The right answer depends upon the setting and the nature of the relationship between the negotiators. Usually a negotiation will have integrative and distributive potential. That is, a negotiation will present opportunities for the parties to offer one another things that increase the size of “the pie,” and the negotiation will present opportunities for the parties to claim slices of that “pie.” A good negotiator looks for integrative and distributive opportunities, making efforts to increase the total value of a deal to both parties, even as the negotiator claims as much value as she can for herself.

NEGOTIATION STYLES

There are two categories of negotiator styles: adversarial and problem solving. Adversarial negotiators approach a negotiation as a zero-sum game: every benefit one party receives is a direct loss to the other party, and winners use tough positional bargaining tactics. Problem-solving negotiators approach negotiations as a non-zero-sum game, where concessions are made by each party in order to create value, and trusting, creative discussions address underlying interests. You should be prepared for adversarial tactics to be employed against you in a negotiation. However, you should also be willing to engage in problem-solving tactics in negotiations. To be sure, negotiations may require one to be adversarial as well as problem solving in order to do what is best for your company so do not dismiss either kind of tactic out of hand.

ADVERSARIAL TACTICS

Extreme opening offers, few and small concessions, withholding information, and manipulating commitments are all adversarial negotiating tactics.3 Let's look at these briefly.

- Extreme Openers—Anchoring. Extreme opening offers are used to take advantage of what psychologists call the “anchoring effect.” That is, the initial offer has a powerful effect on the final agreement. An analysis of a large database of negotiation studies found that for every $1.00 increase in opening offer, we can expect the final sale price to increase by $.50.4 Negotiators can take advantage of the anchoring effect by making an opening offer that is lopsided in their favor. Even when the counterparty forces you to make concessions, you are conceding away from a highly favorable amount toward an amount that is still favorable to you. However, when negotiating with a well-informed counterparty, extreme opening offers can make you look less credible because it suggests you have failed to accurately assess the worth of your good or service.

- Few and Small Concessions—Reciprocity. Concessions are made when the parties realize their stated positions are simply incompatible, and one or more is required to budge. When one party makes a concession, a powerful psychological norm is triggered that encourages the other party to do the same: the norm of reciprocity. Adversarial negotiators will make concessions that grow increasingly closer together to signal to the counterparty that they are reaching their bottom line, below which they will not go. For instance, the aggressive negotiator who has a bottom line selling price of $30 will open with $100, then concede to $75, then to $65, then to $60. This suggests to the buyer that the seller's bottom line is somewhere around $60. When the seller makes a concession, the norm of reciprocity encourages the buyer to make a mirror-like concession. Suppose the buyer's original counteroffer was $30. In order to reciprocate the sellers apparently generous concessions, the buyer will end up offering more each time. To be sure, buyers can use this tactic just as well as sellers, by increasing their offer in smaller increments each time to signal to the seller that they are reaching their maximum offer.

Another concessionary tactic is the “rejection-then-retreat” trick. This involves making an opening offer that you know will be rejected, only to immediately make your real offer that, because of the norm of reciprocity, will more than likely be accepted. Suppose you ask someone to donate $20 to your charity, knowing they will decline, but as soon as they decline, you ask them to purchase a candy bar for $5 instead. This approach is very successful, because the counterparty feels obligated to reciprocate your “generous” reduction in the amount of your request by agreeing to the second offer. Like all adversarial tactics, be wary in the use of concessionary tactics, as a savvy counterparty can detect their use and you may lose credibility or trust as a result.

- Withholding Information. Information asymmetry is the term used to describe a situation where one party has access to information that the other party does not know about. Adversarial negotiators can withhold information to take advantage of information “asymmetries”—that is, the parties' access to information is not equal. For example, imagine you are an oil prospector, and you come to know that a small farm is sitting on a large oil field. The farmer is elderly and relatively uneducated, and has no idea that he is sitting on millions of dollars worth of oil. You approach the farmer and negotiate over the sale of his farm, withholding the information you have about the riches just beneath the surface of his land. The farmer asks for $150,000 for the property, and you counter with $100,000, ultimately agreeing to $125,000 for the property. The farmer walks away believing he secured a good price for his land. By withholding information, you secure an enormous profit for a small expenditure by capitalizing on the information asymmetry with respect to the actual value of the estate. This type of negotiation may be perceived by others as highly unethical, even if it is legal.

One of the risks of withholding information arises when both parties employ the tactic at the same time. This leads to an impasse because neither side knows what the other side's actual position is. Further, this tactic prevents parties from bargaining on the basis of good information about the actual underlying interests of one another. Negotiated outcomes may be less than satisfactory as a result.

- Manipulating Commitments. An adversarial negotiator can use commitments in two ways: binding the counterparty, or binding yourself. In the first kind of commitment manipulation, the negotiator can get their counterparty to commit to a principle, then use that commitment against the counterparty later in the negotiation. For example, you could ask, “Now, you agree that no one should do business with a criminal, right?” and the counterparty agrees in principle. Then you say, “Well, my competitor has been convicted of a crime, so you shouldn't do business with him. Therefore, you should do business with me instead.” This tactic capitalizes on the need for most people to maintain consistency. By getting the counterparty to commit to a principle, you can manipulate them within a negotiation. However, this type of manipulation can backfire in terms of lost credibility and trust if the counterparty views it as trickery.

The other form of commitment manipulation is to bind yourself. You can say, “I simply cannot agree to anything less than $50,000 or I will be fired by my boss.” This sends a clear, forceful message to the counterparty about your bottom line. They will take the $50,000 offer or leave the deal. If you have the most leverage—that is, you have less to lose from walking away from the deal than the counterparty—this can be very effective. However, this type of manipulation of commitments can backfire if you don't have enough leverage. It ultimately constrains your flexibility within the negotiation, and may erode your credibility if the counterparty discovers later that you agreed to something else in a separate negotiation.

PROBLEM-SOLVING TACTICS

Separating people from the problems (listening), focusing on interests rather than positions (asking), inventing options for mutual gain (inventing), and using objective criteria to evaluate the terms (referencing) are all problem-solving negotiating tactics.5

- Listening. Often disagreement can trigger negative emotions which lead to personal entanglement, and the source of the conflict is mistakenly attributed to the person on the other side of the negotiating table. When egos get involved, conflicts can escalate. Good communication begins with good listening. It is crucial to attack the problem, rather than the people. This requires negotiators to separate the people from the problem. Listening carefully can help identify misperceptions—if they are never identified, opportunities for mutual benefit may be lost. Listening also allows a negotiator to acknowledge an emotional conflict, which goes a long way toward resolving the issue. Listening can transform a conversation from a heated argument into a collaborative dialogue. When people feel they are not being heard, they understandably become angry, and the resolution of the conflict recedes until it is out of our grasp. On the other hand, when your adversary feels you are truly listening to them, they are less likely to attribute callous indifference to you, and hence they are more likely to sympathize with your problems as well. Demonstrating that you understand what your counterparty is saying and how they are feeling can help melt the ice and lead to more amicable relations. The technique used to demonstrate that you are listening is “looping”: when the other side responds to your statement, demonstrate that you understand by paraphrasing, and then invite the other side to confirm that you have understood. If the other side confirms that you have understood them, the loop is closed; otherwise, start the loop over. It is crucial for a negotiator to demonstrate listening with authentic, genuine curiosity.

- Asking. Usually, negotiators begin by stating various positions that do not actually reflect their true interests. In other words, positions are usually the means, whereas interests are the ends. Suppose you are selling a stereo to raise money to purchase a new computer. When you say, “I can accept no less than $1,000 for my stereo,” you state a position that is a means to your end of purchasing a computer. However, your counterparty has no idea why you need the money. If the counterparty doesn't have $1,000, the deal is dead. However, if the counterparty asked you why you needed the money, and you were to say, “I need $1,000 because I am trying to purchase a computer,” the counterparty might very well say, “If you accept $500, I can give you my used computer.” Positional statements are used to push back and forth, and usually obscure what the parties truly need from one another. Asking questions about underlying interests allows negotiators to focus on interests rather than positions. Asking “why” can uncover hidden interests that can create opportunities for mutual gain. Ask open questions, not closed questions. To continue the example, an open question would be, “Why do you need $1,000?”, whereas a closed question would be, “Where did you come up with $1,000?” When you ask “why,” clarify that you are not asking for an excuse but rather you are trying to improve your understanding of the counterparty's situation and needs. Be sure to maintain a courteous, genuinely curious tone when you ask questions, otherwise you will come off as interrogating the counterparty, which can erode trust.

- Inventing. Adversarial situations stifle creativity by putting us in a defensive posture. Creative negotiators can find ways out of impasse by inventing various options that reconcile competing interests and promote joint gain. Brainstorming can turn a conflict into a constructive endeavor. Differences between the negotiators can actually help lead to mutually beneficial settlements. Differences in resources, relative valuations, forecasts, risk preferences, and time preferences are more helpful in overcoming obstacles than similarities along these dimensions. By highlighting differences between the parties, negotiators create options and increase the likelihood of discovering a mutually attractive outcome. Remain open to think creatively, and avoid over-committing yourself to any particular dispute resolution. Open brainstorming is the opposite of manipulation through self-commitment.

- Referencing. Instead of forcing a settlement with brute strength, negotiators should evaluate the outcome of a dispute using objective criteria to which both sides can agree. This allows the parties to depersonalize the negotiation. Basing outcomes on what one party is willing to do for the other party is likely to fail in an adversarial negotiation, given the mood. However, using objective standards such as industry norms or market value allows negotiators to get past different personal preferences to reach an agreement that is defensible from any perspective. Using objective criteria can also help a negotiator overcome unfair tactics used by the counterparty.

RELATIONSHIP MANAGEMENT IN PRACTICE

THE KEIRETSU SUPPLIER-PARTNERING MODEL

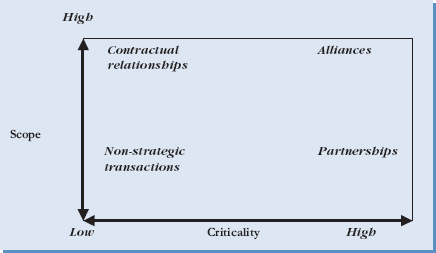

An important issue in supply chain relationship management is how to turn armslength relationships with suppliers based on power-differentials into close partnerships based on trust. The Japanese concept keiretsu applied to supplier relationships can provide a model of this. The concept means a close-knit network of suppliers that continuously learn, improve, and prosper along with their parent companies.

Toyota and Honda have established successful keiretsu relationships with suppliers in North America while American automotive companies have struggled to do so. Figure 11.8 illustrates the six strategic and interlocking steps that should be taken in developing these relationships. The process starts with step 1 at the bottom of Figure 11.8, first developing an understanding of how suppliers work. Progressively the steps build to the top and culminate with developing joint improvement programs with suppliers. Consider how these six strategies effectively counteract the various sources of conflict—particularly data and structural conflict—discussed in this chapter.

PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENTS

Creating a business relationship is usually accompanied by excitement and a sense of opportunity. But like relationships between individuals, success does not come without an honest accounting of one another's expectations and obligations. When disagreement occur, and the contract that created the partnership is either silent or ambiguous with respect to what the parties agreed to, businesses must go to court to litigate the rights and obligations under the contract. Litigation costs are steep enough to persuade reasonable people to expend effort upfront to clarify each other's intentions and understandings.

FIGURE 11.8 Steps in developing a keiretsu partnership6

Questions often arise when the parties do not contribute in the same way. For example, if one party contributes ideas, and the other party contributes money or physical effort, how should these contributions stack up? How long will the parties remain involved? What dispute resolution procedures will the parties use in case of disagreement?

A good example of the need for partnership agreements is offered by Steve Hind, a former AP Middle East Correspondent, and Tom Potter, a banker, who both quit their day jobs and co-founded the Brooklyn Brewery in New York in 1987. Today, the Brooklyn Brewery is one of the top 40 breweries in the United States. These two partners explain in their book—called Beer School—that it is not sufficient to agree to become partners. “Even a dog can shake hands,” they say.7 In the beginning of their partnership they made sure to “draw up a partnership agreement that defined the agreement financially and also defined a buy-sell agreement, in case one of us wanted out or in case of disputes. Over the years, I saw many partnerships dissolve into chaos. They had shaken hands at the beginning, but there was nothing on paper to define what that meant.”

Agreeing to be bound by a formal contract too early in the relationship can create its own set of problems. The businesses must understand one another's capacity to contribute to the success of the supply chain, not simply take one another's word. Like in human relationships, it is important for the parties in a supply chain relationship to know one another before getting too serious.

DILUTING POWER

It is not uncommon for companies to seek out a partner for additional capital, business connections or managerial skills, or to share expenditures. Obviously, these resources do not come for free. Often they are offered in exchange for a portion of ownership, control, or some type of decision-making power. Power is a limited resource that must be divided carefully. Giving too many people decision-making power can lead to a “tragedy of the commons,” an expression used to describe situations where resources are not utilized efficiently because too many people exercise control over them simultaneously.

John Mautner founded a successful glazed nut store, Nutty Bavarian, in Florida. Within four years, he was running 20 retail outlets, and wanted to expand to 200. However, like many business owners seeking to expand, he lacked sufficient capital to do so on his own. That is when he made a big mistake. He sold half of the ownership rights to his company for $1 million. The mistake was not in the price, but in the percentage. When two people have an equal say, it is difficult to break the tie in case of disagreement. This is true of any supply chain relationship.

For three years, Mautner and his new partner fell into conflict over and over again, from where to locate new storefronts to which strategy to utilize going forward. “With a 50-50 partnership, no one could make a call,” he says.8 Mautner's solution was to sell his interest in the company to his partner and try a different approach. Now, Mautner abides by the principle to never relinquish majority ownership. The lesson for everyone is to avoid 50-50 partnerships unless you are in perfect harmony with your partner, which is an empty set.

CHAPTER HIGHLIGHTS

- All supply chain relationships are not of equal importance. Supply chain relationships fall into four categories: non-strategic transactions, contractual, partnerships, and alliances. Non-strategic transactions are cost based and do not require relationship management. More comprehensive relationships, such as alliances, require greater attention to relationship management. The keiretsu model is relevant to developing long-term, mutually beneficial outsourcing relationships.

- Supply chain relationships should be developed and managed on the basis of trust rather than power exploitation. while helping both companies This improves short-term performance and long-term profitability while helping both companies continuously improve. Trust-based relationships are developed by assessing the value of the relationship, identifying operational roles played by each business unit, negotiating effective contracts, and designing effective conflict resolution procedures.

- There are five potential sources of conflict that may arise in supply chain relationships: relationship conflict, data conflict, interest conflict, structure conflict, and values conflict. Turning conflicts into opportunities as they arise between organizations in a supply chain is a highly valuable managerial skill.

- Prepare for negotiations by studying the business of the counterparty, identify who has the most leverage, and think about underlying interests. Try to create value and improve supply chain performance through enhanced relationships. While some situations will require distributive tactics, always look for integrative potential.

KEY TERMS

- Scope

- Criticality

- Contractual

- Relational

- Design phase

- Management phase

- Sequential interdependence

- Reciprocal interdependence

- Relationship conflicts

- Data conflicts

- Interest conflict

- Structural conflicts

- Value conflicts

- Position

- Interest

- Integrative opportunities

- Distributive opportunities

- Adversarial negotiators

- Problem-solving negotiators

- Keiretsu

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- How are supply chain relationships similar to and different from personal relationships?

- Can you think of a conflict between units in a supply chain in real life? What kind of conflict was it? How was it resolved? Would you have resolved it differently?

- Identify examples of a supply chain where relationship management is not very important. Identify examples of a supply chain where relationship management is crucial.

- Do you perceive yourself as a competitive or problem-solving negotiator? Can you think of situations where you may have to adopt a different negotiation style?

CASE STUDY: LUCID V. BLACK BOX

Lucid is an up-and-coming Chilean distributor of home entertainment technology. Black Box is a well-known television manufacturer headquartered in the United Kingdom. Black Box was interested in reaching out into the South American market, and found Lucid to be sufficiently well connected to reach customers throughout the continent. In January of 2008, Lucid signed an exclusive three-year contract to establish a distribution network for Black Box High-Res flat screen televisions throughout South American using Black Box's logo. The contract included the following provisions:

- Lucid has the exclusive right to sell Black Box's High Res televisions and any updates to the High Res product line.

- Lucid must establish a distribution network within the agreed region.

- Lucid must order 4,300 High Res televisions or £1,000,000.00 worth of product before January 1, 2011.

- If Lucid fails to meet these conditions, Black Box has the right to rely on other distributors within South America.

- If either party is in breach of this contract, the non-breaching party may terminate this agreement after three months notice.

In August 2008, Lucid placed an order for 1,000 High Res television sets, but the shipment was delayed for several months with no explanation from Black Box. Lucid was frustrated because Black Box's delay in shipment caused Lucid to be late in supplying the televisions to the retailers with whom Lucid had contracted. As a result, some of these retailers terminated their agreement with Lucid before the shipment finally arrived, leaving Lucid with a surplus of High Res televisions and in need of new retailers.

In June 2009, Lucid placed an order for 1,000 High Res television sets, which arrived shortly thereafter. Lucid discovered that a few retailers had High Res televisions with Black Box logos in stock, despite that they were not contracting with Lucid. Lucid believed that Black Box must have contracted directly with these retailers, or perhaps relied upon other distributors in violation of the exclusive contract. Either way, Lucid was frustrated that Black Box was competing with them in their agreed-upon distribution region.

In November 2009, Black Box released a new television, the 3-D Flat Screen, and began marketing this in South America. Lucid wrote an angry letter to Black Box because Lucid believed they had the exclusive right to market updates to the High Res product line. Black Box replied that the 3-D Flat Screen was in a distinct product category from the High Res line, so the contract did not apply.

In June 2010, Lucid was still far from reaching the minimum order requirement in the contract, but felt this was due to the actions of Black Box. Then Black Box sent Lucid a termination letter that stated Lucid had failed to establish a distribution network to their satisfaction. Fed up with Black Box's poor communication and feeling as though they had been treated unfairly, Lucid executives met with their legal advisors and asked what their options were. The attorneys for Lucid say there are four options available: Lucid can litigate, arbitrate, mediate, or negotiate with Black Box to resolve this dispute.

CASE QUESTIONS

- What are the sources of conflict between Lucid and Black Box?

- Which dispute resolution procedure should Lucid use? Why?

- If Lucid decides to negotiate with Black Box, what kind of negotiation tactics should be employed?

- How can Lucid and Black Box improve their supply chain relationship?

REFERENCES