Chapter 13

Sustainable Supply Chain Management

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

- Define sustainability and explain its role in supply chain management (SCM).

- Identify environmental and social costs inherent in supply chain activities.

- Describe methods of measuring and implementing sustainability.

- Explain the supply chain sustainability model.

- Identify specific changes organizations can make to support a sustainable supply chain.

- Make a business case for sustainable SCM using concepts and examples from this chapter.

![]() Chapter Outline

Chapter Outline

- What is Sustainability?

Defining Sustainability

Environmental and Social Sustainability

Environmental Sustainability

Social Sustainability

Principles of Sustainability

Why Sustainability?

Legal Compliance

Community Relations

Revenue

Ethical Responsibility

- Evaluating Sustainability

The Supply Chain Sustainability Model

Enforcement, Compliance, and Innovation

Enforcement

Compliance

Innovation

Measures of Sustainability in SCM

Values in Sustainable SCM

Cost Assessment

Cost-of-Control

Damage Costing

Costing Systems

Risk Assessment

“Fat Tails”

Scenario-Based Analysis

Fuzzy Logic

Monte Carlo Simulations

Real Option Analysis

- Sustainability in Practice

Product Design

Packaging

Sourcing

Process Design

Marketing Sustainability

Unintended Consequences

- Chapter Highlights

- Key Terms

- Discussion Questions

- Case Study: Haitian Oil

On April 20, 2010, a deep-sea oil rig owned by British Petroleum PLC exploded. The explosion immediately killed 11 rig workers and caused the release of almost five million barrels of crude into the Gulf of Mexico as the broken pipe on the ocean floor spewed oil until September 19, 2010. The depth of the well, combined with hurricane-season weather within the Gulf of Mexico, made stemming the flow of oil a prolonged, expensive, and technically challenging project. The price of crude oil at the time was averaging over $80 per barrel. That amounted to about $400 million lost in product waste alone, without counting environmental degradation in the form of marine and wildlife habitat destruction, fishing and tourism business losses along the Gulf Coast, clean-up costs, stock price decrease, or the loss of human life.

According to the report of the United States' National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling, the oil spill was “an avoidable disaster that resulted from management failures by BP PLC and its (two) contractors,” and that “all three companies did a poor job of assessing the risks associated with their decisions and failed to adequately communicate, either with one another or with their own employees.” While some have dismissed the Deepwater Horizon disaster as an irresponsible aberration on the part of the three companies, not to be expected from others in the industry, the report suggests otherwise: “The root causes are systemic and, absent significant reform in both industry practices and government policies,” could very well happen again with other companies.

BP suffered an astounding 52% decrease in stock value within 50 days of the explosion as a result of negative shareholder reactions. To avoid litigation over the matter BP created a $20 billion spill response fund to compensate for natural resource damages, government response costs, and individual compensation. In order to finance the compensation fund, BP plans to significantly reduce capital spending, divest about $10 billion in assets, and reduce payment of dividends to shareholders. These are all potentially ruinous consequences for the company itself, not to mention the environmental and social impact.

In order to achieve environmentally and socially sustainable performance, companies must be aware of the costs and risks that surround their actions. From resource extraction to product disposal, sustainable supply chain management (SCM) promises to achieve long-term corporate profitability while protecting the environment and human welfare. As demonstrated by the Deepwater Horizon disaster, companies can pay an extremely high price for failing to anticipate low probability, high consequence events. While not all sustainability issues are as dramatic as this example, many have severe consequences for both the organization and the environment. Fortunately, they can be avoided by adequate care and attention to costs and risks, effective leadership and communication, responsiveness to stakeholders such as employees, surrounding communities, and government, and a policy of minimizing environmental and social risks while maximizing long-term corporate profitability.

Adapted from: The Wall Street Journal, A2, January 6, 2011, and www.bp.com.

WHAT IS SUSTAINABILITY?

DEFINING SUSTAINABILITY

The last few decades have seen increased demand for companies to fully account for the environmental and social impact of their products and services, and the associated supply chains. The activities involved in SCM impact these concerns—including biodegradable product packaging, responsible product disposal, control of manufacturing and transportation emissions, and sustainable sourcing practices. As a result, sustainability has become a central theme in SCM.

While indispensable to our daily lives, supply chains can have significant adverse environmental and social consequences. These include environmental costs, health and human safety risks, and the cost of waste. Sustainable SCM is concerned with changing practices to reduce these negative consequences. Sustainability impacts SCM in areas of product design, product manufacturing, packaging, transportation and logistics, sourcing, and product end-of-life. As consumers increasingly demand environmentally and socially sustainable products businesses are being forced to find ways to achieve sustainable supply chain performance. As a result, the challenge to managers posed by sustainability is to incorporate environmental and social responsibilities into their management practices.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch

For decades, ocean currents circulating between the coasts of California and Japan have accumulated plastic waste into a gyre of non-biodegradable garbage known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. This is a whirling mass of garbage floating in the middle of the ocean. In fact, there may be as many as five garbage patches in the Earth's oceans. The garbage patches are made up of plastic bits from toys, bottles, and packaging that find their way into the ocean from storm sewers, as well as pollution left from marine vessels. Winds drive the surface-level pollution toward the center of the gyre where the currents are relatively still and the garbage cannot escape. Sunlight breaks down the garbage into microplastics that are loaded with toxins, with the plastics functioning as a sponge, amassing large concentrations of toxins from the surrounding ocean water.

When the plastics degrade into tiny particles, zooplankton and other life forms at the bottom of the marine food chain consume the garbage that is ultimately passed up through the food chain. Marine wildlife, such as sea turtle, albatross, and jellyfish, consume the plastic particle, leading to death or hormone disruption. Toxins in the garbage patch can wind up back in the human body, threatening our health.

Estimates of the size of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch range up to twice the size of the continental United States, but it is difficult to measure its actual span and density. The open-sea garbage patches contain plastics that have broken down into smaller polymers, as well as chemical sludge and larger debris such as abandoned fishing nets. They are an indirect consequence of the use of non-biodegradable plastics in consumer products and packaging. While efforts to clean up the patch are underway, scientists suggest that relying on nontoxic, biodegradable and recyclable materials is the only way to prevent such phenomena from recurring.

Sustainability can be defined as meeting present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. Sustainability is indispensible when both present and future generations depend upon the same set of limited resources. The resources of the Earth used on the input side of supply chains are borrowed from the future and must be stewarded as such. For example, if the present need for timber was consumed at an unsustainable rate, trees would be cut down faster than they could be re-grown, which would compromise the ability of future generations to access timber. The waste output of supply chains must be disposed of responsibly. Otherwise, concentrations of pollution can jeopardize the integrity of ecosystems or human health.

While typically defined in terms of the relationship between the present and the future, sustainability is not limited to the intergenerational context. Principles of sustainability also apply to balance competing needs. For example, sustainable use of timber for lumber would not jeopardize the need to access timber for the purposes of making paper. Sustainable resource consumption or pollution would not eliminate resources faster than they could be replenished. Sustainability is not simply for the sake of future populations, but for present purposes as well.

SCM must fulfill consumer demand sustainably. Sustainable SCM requires managers to identify sustainability “issues” when analyzing operations and their effects. In order to determine whether a supply chain is operating sustainably, managers must focus on both inputs and outputs of each stage of the supply chain, as shown in Figure 13.1. Sustainability analysis of inputs requires all aspects of resource consumption—from raw materials to human resources. A sustainable supply chain avoids consuming so much of a resource that future operations are compromised. Sustainability analysis of outputs involves all aspects of pollutant emissions, so that the health of neighboring ecosystems or populations is not put in jeopardy.

FIGURE 13.1 Sustainability considers inputs and outputs of each SC member.

Sustainable SCM is not just an altruistic effort. There are four documented types of payoffs that come with improving a company's sustainability performance. Financial payoffs include reduced operating costs, increased revenue, lower administrative costs, lower capital costs, and stock market premiums. Customerrelated payoffs include increased customer satisfaction, product innovation, market share increase, improved reputation, and new market opportunities. Operational payoffs include process innovation, productivity gains, reduced cycle times, improved resource yields, and waste minimization. Organizational payoffs include employee satisfaction, improved stakeholder relationships, reduced regulatory intervention, reduced risk, and increased organizational learning. We will look at all of these throughout this chapter.

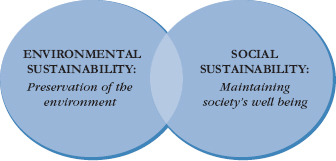

ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL SUSTAINABILITY

Stated most generally, sustainability is the capacity of a system to endure. As such, sustainability is a broad concept with numerous applications. There are two types of sustainable practices: environmental sustainability and social sustainability. Environmental sustainability is the preservation of diverse biological systems that remain productive over time. Social sustainability involves maintaining societies' long-term well-being. While the criteria for sustainability in ecology are different from the criteria for sustainability in human affairs, the two are mediated by supply chain networks. From the extraction of raw materials to the deposit of final waste products, supply chain networks are the links between human activity and the natural world. Social sustainability depends in part on the benefits of environmental sustainability, such as access to clean water, soil and air and healthy ecosystems. Some human activities, such as overfishing and excessive pollution, have an adverse impact on environmental integrity. Threats to environmental sustainability, such as oil spills, acidification, or natural resource depletion, have an adverse impact on humanity's welfare. Therefore, environmental and social sustainability are interconnected, as shown in Figure 13.2.

FIGURE 13.2 Environmental and social sustainability are interconnected.

Environmental Sustainability. Environmental sustainability is the sustainability practice that deals with either pollution or resource depletion issues. Whether a supply chain network is environmentally sustainable depends on the relationship of the activity in question—say resource procurement or manufacturing—to global warming, acidification, smog, ozone layer depletion, toxin release, habitat destruction, land use issues, and resource depletion.

Social Sustainability. Social sustainability consists of either economic or population issues. Whether a supply chain network is socially sustainable depends on the relationship of the activity in question to social issues. These include income inequalities, population growth, levels of migration to cities, gender equality and women's rights, poverty, dislocation, and urban or minority unemployment.

Aracruz Celulose

Aracruz Celulose is a Brazilian company responsible for 24% of the global supply of bleached eucalyptus pulp. This material is used to manufacture printing and writing paper, tissue paper, and high-value-added specialty papers. Eucalyptus lumber is also used to create high-quality furniture and interior designs. Chances are that you have used paper or furniture from Aracruz's lumber. Aracruz is an example of a global company that has developed their supply chain while being committed to environmental and social sustainability. They also demonstrate the financial benefits that can come from such practices.

Aracruz ensures environmental sustainability by preserving the natural ecosystems surrounding the eucalyptus plantations. The company created a forestry management program to preserve native tree populations and prevent overharvesting. They created a watershed project to preserve the quality of nearby rivers in light of insecticide and fertilizer runoff. They also use strict environmental control technology to protect and monitor the impact of their operations on forests and rivers.

In addition to environmental sustainability, Aracruz also focuses on social sustainability by contributing to the communities near their operation sites. The company collaborates with non-governmental organizations, project experts and financial advisors to give back to the local communities. In 2004, Aracruz contributed $5 million to improve the education, health, and social welfare of local populations. Also, Aracruz employees are also encouraged to volunteer in the surrounding communities. Volunteer activities include collecting warm winter clothing, collecting food items to feed the hungry, providing emergency support after catastrophic floods, visiting hospitals, and tutoring local students in economic issues by allowing them to run a “minicompany.”

Aracruz's sustainability strategy is expressed by the brand “Deeply Rooted Assets,” which signifies the company's principled commitment to long-term environmental and social benefits to the Brazilian land and people. The Dow Jones Sustainability Index (DJSI World) highlights the world's best corporate sustainability practices and chose Aracruz as one of the featured companies in 2008.

From: www.aracruz.com.br.

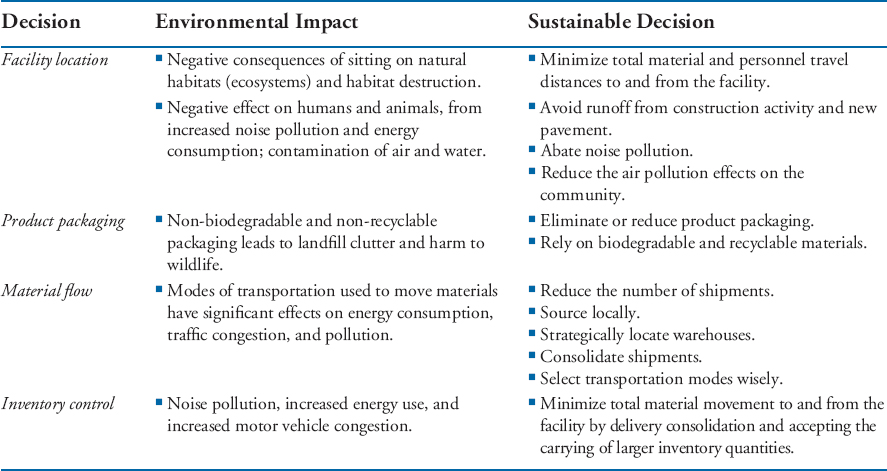

To provide a simple illustration of what a sustainability analysis would include, consider the logistics decision of locating a chemical processing facility. Initially, the choice of location would be determined by considering economic factors, such as real estate cost or transportation, as we discussed in Chapter 7. However, sustainability requires an analysis of environmental and social factors that go well beyond these basic economic considerations, as shown in Figure 13.3. A chemical factory may affect nearby plant and animal populations as well as local human health by introducing air, water and noise pollution. Further, the choice of location may implicate job availability and commuter behavior, while requiring decisions about wages for local employees.

FIGURE 13.3 SCM decisions and related environmental effects.

Adapted from: Beamon, Benita. “Environmental and Sustainability Ethics in Supply Chain Mamagement.” Science and Engineering Ethics. Vol. 11, No. 2, 2005, 221–234.

PRINCIPLES OF SUSTAINABILITY

Being able to spot critical sustainability issues, and offer adequate solutions, is a crucial managerial skill in today's business environment. For key “issue spotting” tools, consider the following nine principles of sustainability:1

- Ethics. Ethics involves promoting a corporate culture that fosters truthful and fair conduct between all stakeholders. Ethics are maintained by monitored and enforced codes of conduct. At the bare minimum, an ethical company prohibits violations of human rights or dignity, and adheres to honest and just standards and practices. Positions such as a “corporate ombudsmen” can be used to ensure that external stakeholder voices are heard, as well as an “organizational ombudsmen” to ensure internal stakeholders are respected. This helps create a work environment that encouraged the reporting of ethical violations to appropriate authorities by offering a confidential and neutral forum to voice concerns.

- Governance. Governance concerns the conscientious execution of duties held by corporate board members and managers. Good governance requires a well-understood mission statement supported by performance metrics, as well as the use of decision tools to support management. Good governance should mandate the evaluation of senior management along multiple dimensions, such as sustainability measures, not merely financial performance.

- Transparency. Transparency involves visibility. Companies that care about the information needs of others are transparent with them. Full disclosure of financial performance is important with respect to investors or lenders. There are different degrees of transparency—ranging from document disclosure upon request to posting information publicly.

- Business Relationships. Companies should treat all suppliers, distributors, and partners fairly. They should also deal only with companies that do the same. When forming business partnerships, or seeking sources of supply, they should also consider social, ethical, and environmental factors as selection criteria. Not doing so can put a company's reputation in jeopardy.

- Financial Return. To raise capital, companies must provide investors and lenders with a competitive return on investment (ROI). The company should maintain solid financial results and continue to create value, while balancing additional nonmonetary factors. Although positive financial returns are necessary, they should be evaluated in conjunction to other principles of sustainability.

- Community Involvement and Economic Development. Investing in community involvement and economic development improves the economic welfare of the community in which the company does business. It serves to enhance the company's long-term profitability by creating additional opportunities in that community. Starbucks invests heavily in the communities of coffee growers. The result is a reliable and consistent source of supply.

- Value of Products and Services. Companies typically state a general commitment to customer satisfaction, as part of their mission statement. However, they should clarify their obligations and responsibilities to their customers. In addition to products and services being of the highest quality, managers should be aware of the externalities generated by their products or services, and their supply chains.

- Employment Practices. A diverse workforce with competitive wages and ample time away from work is bound to be a more loyal, productive workforce than one that is subject to prejudicial abuse, grueling hours, and poor pay. Management practices with respect to employees should go above and beyond minimum requirements of health, safety, and nondiscrimination mandated by labor laws. Employment practices should maximize the productivity and quality of employees by fostering a culture of mutual respect, appreciation, and care in the pursuit of the corporate mission. Investing in employees, in the form of continuing education programs, leave time, childcare, and opportunities for advancement, are ultimately investments for the company itself. The result is healthier, happier, more productive employees, and an enhanced reputation of the company. An excellent example of these benefits is the SAS Institute in North Carolina, a company consistently on Fortune Magazine's top companies to work for. The company provides a superb work environment—from childcare to on-site massages—resulting in high productivity and almost no turnover.

- Protection of the Environment. At a bare minimum, all corporations must comply with applicable environmental laws. However, corporations can do much more than this to promote environmental integrity. Innovations that allow corporations to meet demand while simultaneously cutting waste, lowering air and water pollutants, and consuming fewer resources are genuinely praiseworthy. Maximizing the use of recyclable materials, increasing product durability, streamlining product packaging, and encouraging stringent safety standards are all management decisions that can be made internally. Allocating resources to fund research into cleaner, more efficient technology, or to fund land reclamations, or to create wilderness preservations are all means of stewarding corporate capital to offset corporate environmental harms.

These principles are all relevant to a company's sustainability performance. In evaluating the sustainability of a company, analysis should consider these dimensions. Managers should be familiar with them and seek to incorporate them when making decisions.

WHY SUSTAINABILITY?

The anti-environmental posture prevalent in industry poses an obvious barrier to voluntary sustainability initiatives. This posture stems in part from two paradigms for thinking about environmental management. The “crisis-oriented” environmental management paradigm considers the purpose of management to protect and enhance business performance in terms of making more money, which encourages uncooperative behavior toward anyone with a countervailing agenda, including environmental advocates. The “cost-oriented” environmental management paradigm considers environmental regulations as simply a cost of doing business. Corporations will pollute as much as necessary to profit from the polluting activity, and will count environmental sanctions as one more cost of operations on the balance sheet. Both of these paradigms place priority on business profitability, viewing environmentally sustainable measures as a barrier to that end.

Why implement sustainable measures in SCM? There are at least four reasons:

- Legal compliance with government regulations

- Maintain positive community relations

- Increasing revenue

- Satisfy moral obligations

We look at these next.

Legal Compliance. Environmental regulations typically define two sets of standards which must be adopted by major sources of pollutant emissions. The first is a design standard, which specifies the type of technology necessary for the pollution source to be in compliance with the regulation (e.g., a certain type of pollution-scrubbing filter must be installed on a smokestack). The second is a performance standard, which specifies the amount of permissible pollution (e.g., effluent pollution must be reduced to x parts of pollutant per million parts water), leaving the choice of pollutant reduction technology to the polluter. Failure to comply with environmental regulation can result in penalties, fines, litigation costs, increased inspections leading to lost productivity, plant closure, and bad press (not to mention potential environmental and human health consequences).

International norms are also relevant to corporate sustainability. While not a binding law, the United Nations Millennium Development Goals are the product of a gathering of 2000 world leaders, and include goals such as the elimination of extreme poverty, the promotion of gender equality and female empowerment, and the attainment of environmental sustainability. The poverty goal entails reducing the number of people living on less than $1 per day and achieving full and productive employment for all people. The gender equality goal entails increasing the share of women in wage employment in non-agricultural sectors. The environmental goal entails integrating sustainable principles into policies and programs, as well as reversing the loss of biodiversity and environmental resources. Clearly corporate activity can either advance the world toward meeting these goals, or undermine our ability to meet these goals.

Community Relations. Another reason to implement sustainability is to effectively manage community relations. Failure to operate a company sustainably can lead to stigma and lost trust from the community. Consumers will cease purchasing from a company who they feel is not loyal to the interests of the community in which business is done. Negative reputation with stakeholders can negatively impact the financial bottom line of a company. Just consider the community relations issues BP encountered following the Gulf oil spill.

Revenue. Managers are perennially aware of the need for minimizing costs and maximizing revenue—in other words, creating financial value. Sustainability offers a means to this end. Financial value can be created by lowering operating costs through the adoption of more energy-efficient technology. Further, financial value can be created by process improvements such as lean manufacturing principles, eliminating steps that are unduly burdensome, and eliminating barriers to smooth flowing processes.

Ethical Responsibility. An additional motive for implementing sustainability principles stems from our sense of moral obligation to preserve life. Hypoxia is the condition of oxygen depletion in aquatic environments that threatens life forms. Caused by pollution and eutrophication from run-off, hypoxia leads to “dead zones” where shark, fish, and invertebrate carcasses can be seen strewn across the ocean floor. Companies concerned that their production processes are causing hypoxia can adopt more effective sewage treatment to prevent pollutants and fertilizers from leaching into bodies of water. Doing so would be motivated by a moral concern for the preservation of living creatures, or simply out of self-interest for our access to fish for consumption.

Whether we care for the environment because it is intrinsically valuable or because it ultimately serves our own ends, our moral radars should consider the welfare of living creatures. Additionally, morality would prohibit imposing harms on individuals who do not consent to be put at risk. This moral concern would motivate a company to adopt pollution control technology to decrease the amount that surrounding communities are exposed to airborne or waterborne pollutants. If a company knew that emissions from a manufacturing plant were directly responsible for the cancer of many locals, even though the plant was in compliance with environmental laws, managers with sensitivity to moral considerations would protect nearby human lives by taking measures to reduce carcinogenic emissions from their plant. A desire to fulfill our moral obligation to avoid unnecessary harm serves to motivate sustainability.

There are at least three different frameworks for thinking about ethical duties to adopt sustainable practices: minimalism, reasonable care, and good works. A minimalist ethic views precautions as worthwhile simply to avoid liability. A reasonable care ethic takes available measures to eliminate foreseeable risks either by designing out the risk or providing protection against the risk. A good works ethic goes beyond what is legally required to take affirmative steps to discover potential hazards and proactively safeguard society against them. Regardless of which of these moral perspective one adopts, most of us view human welfare as intrinsically valuable, and environmental welfare is worth protecting because of its “instrumental” value for humans. Even under this human-oriented framework, proactive measures to preserve environmental integrity are justified as means of bolstering human welfare.

Governmental regulations, public relations, cost imperatives, and moral obligations are all rationales for sustainability in SCM, and these rationales are interconnected. Failure to adopt sustainable practices can lead to fines for regulatory noncompliance, which negatively impacts the financial bottom line by exacerbating operating costs. Further, noncompliance likely causes some environmental or human health damages, which tarnishes the company's reputation, and possibly compromises the moral obligations of managers to avoid imposing uncompensated harms on others. Instead of asking, “Why should we operate sustainably?” the presumptive question should be, “Why not operate sustainably?”

EVALUATING SUSTAINABILITY IN SCM

Managers are under the burden of balancing the influences of resource availability, customer demand, consumer activists, employee loyalty, and government regulations. In this section we present a model that integrates social and environmental impacts into a company's supply chain management strategy.

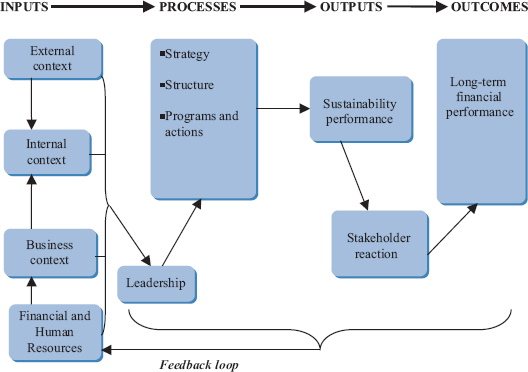

FIGURE 13.4 The Supply Chain Sustainability Model.

Adapted from: Epstein, Marc J. Making Sustainability Work: Best Practices in Managing and Measuring Corporate Social, Environmental, and Economic Impacts. Sheffield, UK: Greenleaf Publishing, 2008. p.46.

THE SUPPLY CHAIN SUSTAINABILITY MODEL

The Supply Chain Sustainability Model provides the elements of a successful sustainability strategy and shows how they are related. It is illustrated in Figure 13.4. The continuum presented in the model includes inputs that feed into organizational and supply chain processes, and lead to outputs.

The model shows that management decisions—in the form of processes and organizational and supply chain structures—create an environmental and social impact. Supply chain sustainability performance, in turn, leads to stakeholder reactions that then impact long-term financial performance. A feedback loop connects processes, outputs and outcomes, indicating a shift in the inputs as a result of performance. Processes, outputs, and outcomes define the costs and benefits of supply chain activity. Processes also have an immediate effect on long-term financial performance. As shown, financial performance is affected by the stakeholder reaction to sustainability performance. The following expands upon each of the elements of this model.

Model Inputs. The external context of SCM pertains to government and market-based influences. In all countries, government regulations impose burdens on industries to follow minimum health and safety standards, although their stringency varies by location. This includes the disposal of hazardous or toxic waste, various emissions pollutants, employee discrimination, safe working conditions, minimum wages, and the minimum age of employees are all subject to regulation. Similar to governmental regulations, market influences on the sustainability model depend upon where the company does business. The marketplace for products and services will reflect consumer tolerance for pollution, among other things. Other factors such as weather patterns, topography, population wealth, and access to information also sway the market's response to corporate sustainability decisions.

The ability of a supply chain to become sustainable also depends upon its internal context. Not only the pressure to increase revenue and pay dividends to shareholders, but the mission statements, dominant strategies, organizational structures, decision-making procedures and operating systems within each business unit of a corporation form the internal context of sustainability. Each element in this context may have a positive or negative effect on efforts to achieve sustainability and should be critically evaluated in light of its tendency toward efficient, sustainable operations.

Different industry sectors will have to deal with unique issues stemming from different business contexts. For example, energy, chemical, and mining industries will create risks to the environment and human health, whereas service industries and product manufacturers may pose social risks in terms of working conditions and consumer relations. Companies with the greatest potential to gain or lose from sustainability initiatives include companies with high-profile brands, companies whose supply chains carry significant environmental impacts, companies who significantly depend upon natural resources, and companies that face current or potential regulatory exposure. Uniform labor and inspection standards as well as industry codes of conduct are responses to pressures arising from the business context.

Sustainability performance is greatly affected by the human and financial resources committed to its achievement. The implementation of sustainability programs requires a significant upfront allocation of company resources. This resource investment should pay for itself in the long run in terms of avoided costs, but upfront capital is needed to adequately educate pertinent employees to detect sustainability issues. Further, these employees must be equipped with sufficient resources to act on revelations of risk.

Leadership. Leadership involves factoring all the “inputs” (external, internal and business contexts, as well as human and financial resources) into management decisions. The most effective leadership comes from a clear commitment to sustainable performance on the part of top management that is effectively communicated through all the layers of the organization. Leaders must be sufficiently knowledgeable and committed to their vision to translate it into actual performance. Creating a vice president position to oversee sustainability, including major business unit managers on a sustainability committee, and joining with suppliers, are ways of ensuring sustainability issues are addressed from the top down. Leaders must demonstrate commitment to sustainability, search for risks and opportunities associated with sustainability, and foster a sustainable corporate culture.

Processes. A sustainability strategy is a plan that guides the company and it supply chain toward long-term profitability that protects consumers, employees, and the environment. This strategy is put into place by a combination of internal structures and programs.

Sustainability can be promoted through changes in organizational design, such as the creation of a sustainable structure. Rather than relegating sustainability concerns to one department within an organization—such as operations or human resources—responsibility for sustainable performance should be diffused within each function of the company. Such a structure enables each operating unit to see the costs and benefits of its environmental and social responsibility. Sustainable structures should be integrated throughout the organization and between supply chain members, capitalize on human resources and provide feedback on sustainability performance from management to top leaders.

Management systems, such as programs and actions, must be aligned in order to achieve sustainability. Programs to promote sustainability should tie incentives and rewards with effective environmental and social sustainability performance. This requires evaluation of economic, environmental, and social factors in assessing performance, not simply an evaluation of quarterly earnings. Sustainability actions can be either proactive or reactive, depending upon when risks are identified. Further, sustainability actions should be both internal (such as training employees or site audits) and external (such as supplier audits and public accountability).

Sustainability Performance. Sustainability performance is the overall metric designed to reflect organizational performance along multiple dimensions. This metric incorporates all positive and negative impacts on all of the company's stakeholders. Sustainability performance can be enhanced by reducing negative impacts or increasing positive impacts and preferably both. Regardless of how sustainability performance is measured it is necessary to evaluate performance, recognize impacts, and look for improvement. One of the most critical variables in evaluating corporate sustainability performance is the definition of stakeholders. A narrowly defined set of stakeholders, such as shareholders in the company, will probably omit a significant array of impacts that accrue to individuals who do not own stock in the company, and thus reflect a higher sustainability performance score. A broadly defined set of stakeholders would probably lead to a greater estimate of costs, and hence a lower sustainability performance score.

Stakeholder's Reaction. Given the many potential stakeholders, listening and responding to stakeholder reactions is easier said than done. However, ignoring stakeholder reactions is done at the peril of the supply chain's profitability. At minimum, supply chains should consider impacts of their activities on shareholders, customers, suppliers, employees, and surrounding communities. Stakeholders can react in positive and negative ways. Customers can remain loyal or boycott. Talented employees can migrate to more sustainable employers. Regulators and surrounding communities can exert pressure on major polluters. Shareholders may use sustainability as a criterion for investment decisions.

Financial Performance. The monetization of the impact of supply chain activities allows managers to evaluate sustainability initiatives in light of the ultimate goal: improved financial performance. The notion that supply chain sustainability enhances revenue and lowers costs has broad support. Social reputation is a significant success factor in an informed, competitive market. Process improvements can lead to multi-million dollar energy savings and increase shareholder return on investment. Further, sustainable decisions can lead to decreased incidents of legal fees and penalties as well as lower packaging and distribution costs. Internally, companies that invest in the health and welfare of their employees realize benefits in terms of increased productivity and employee loyalty. The supply chain sustainability model allows us to make a business case for sustainability by relating environmental and social impacts to financial performance.

Feedback. Effective feedback loops enable leaders to take data relating to outputs and outcomes and translate them into improvements in internal processes. In order to be useful toward the goal of sustainability, feedback mechanisms must not rely solely on monetary information but must include performance criteria relating to environmental, social, and economic matters. Feedback mechanisms are essential for organizational learning and allow each supply chain member to continue to assess their progress toward long-term goals.

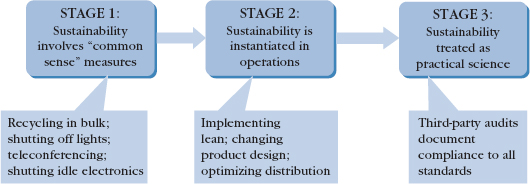

ENFORCEMENT, COMPLIANCE, AND INNOVATION

Adopting principles of sustainability does not happen accidentally. Owners, directors, and managers must conscientiously and resolutely decide to implement sustainability in their supply chains. There are three drivers of sustainable initiatives. They are enforcement, compliance, and innovation—or a mixture of all three. Let us look at these in a bit more detail.

Enforcement. Governmental decision makers can require companies to adopt practices that are deemed environmentally safe and socially responsible, using laws and government regulation. With powers of official oversight accompanied by sanctions for noncompliance, these agencies can enforce sustainable initiatives. For example, the United States Clean Air Act authorizes the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to enact and enforce mandatory regulations that apply to companies that own major pollutant-emitting facilities.

Compliance. Compliance is voluntary participation in sustainable practices. A popular way of encouraging compliance with sustainability has been through industry-initiated certification programs. These programs provide benefits to firms in the form of advertising—such as logos that appeal to the preferences of a growing number of environmentally conscious consumers—and group membership— which provide directory listings and other perks. Rather than imposing sanctions, failure to comply with voluntary programs leads simply to the withdrawal of the firm's membership with the host organization, and the revocation of certification for the firm's products or services.

Innovation. Motivated by internal initiatives, companies may be driven to innovate over current practices in order to enhance operations. Often an incidental benefit of this is the satisfying of environmental or social priorities. Unlike enforcement, innovation is voluntary. Unlike compliance, innovation is internal. What a company's environmental and social goals are, and whether they have been achieved in measureable ways, are not necessarily disclosed to consumers, or if they are published, the data are used as “bragging rights” by the company.

In practice, these three implementation methods exist in hybrid form. Imagine a large company that emits a great magnitude of pollution in operations that span several countries. This company would be subject to various governmental enforcement measures, would probably voluntarily comply with some industry-sponsored certification programs, and would internally fund research and development to promote sustainable innovation. In this case, all three drivers—enforcement, compliance and innovation—overlap in realizing sustainable supply chains. These drivers succeed at achieving independent oversight to ensure actual sustainability. While it appears obvious to everyone that some level of enforcement is necessary, the precise level of enforcement remains an open question.

Implementation of sustainability usually happens incrementally, with companies and their supply chains moving through three stages. This is illustrated in Figure 13.5. First, companies begin incorporating common sense measures such as recycling in bulk, shutting down idling electronics, turning off lights when not in use, and using teleconferencing instead of travel for meetings. The goal at this stage is simply to reduce the carbon-footprint or other metric of sustainability. Second, at more sophisticated levels of sustainable management, sustainable principles become instantiated in operations. Companies begin to conduct internal assessments to reduce the adverse impacts of their operations on surrounding environments. This stage involves implementing lean principles, rationalizing manufacturing, strategic sourcing, changing product design, and optimizing distribution channels. Third, the most refined perspective with which to approach sustainability, treats sustainability as a practical science. At this stage, third-party audits provide an objective framework against which to evaluate organizations and standards are set by governmental or industry groups.

FIGURE 13.5 Stages of sustainability implementation.

MEASURES OF SUSTAINABILITY IN SCM

Sustainable SCM enables a firm to meet the triple-bottom-line of social responsibility, environmental stewardship, and economic viability. There are several approaches to measuring whether a product or service is sustainable.

Total cost of ownership (TCO), which we discussed in Chapter 7, is a measure that considers economic viability by estimating the sum of all costs of a product, including procurement, manufacture, distribution, usage, and disposal. Consider a frozen pizza or a car battery. Both products involve gathering component parts, combining these parts into a product, shipping these products to retail, using the product, and efforts to dispose of the residual material. Of course, the costs at each step in the supply chain would widely vary, and would involve distinct risks. The frozen pizza seems as a relatively benign product until one considers the total costs: the product requires the consumption of trees for packaging, consumption of energy in freezing, and consumption of energy in baking. The car battery's most salient risk is in terms of end-of-life: improper disposal of car batteries can pose significant negative effects on the environment. The total cost of ownership approach helps us consider the costs of a product that are not reflected in its individual price tag.

Life-cycle assessment (LCA) is an approach that considers environmental stewardship by analyzing the environmental aspects and potential impacts associated with a product, process, or service. For example, certain lines of products require energy intensive manufacturing methods, where energy is predominantly supplied by coal-powered electricity plants. In evaluating the sustainability of this product, the LCA would consider the environmental consequences of coal combustion corresponding to the amount of energy generated by that combustion used to manufacture the product. Therefore, the LCA broadens the scope of costs visible to the manufacturer.

Ecological footprint is a metric, similar to LCA, which is sensitive to environmental degradation concerns. However, unlike LCA, it focuses on the consumer rather than the producer. This approach quantifies the land and water area a population requires to produce the resources it consumes and to absorb its wastes. Take for example, hamburgers. In evaluating the sustainability of hamburgers as a food product, the ecological footprint approach asks how much land is necessary to grow the corn that is used to feed the cattle—and how much land is needed for the cattle. Therefore, we can spatially represent the impact of product choices by consumers.

The carbon footprint is an ecological footprint metric that measures the amount of carbon released into the atmosphere, which is correlated with adverse effects on climate stability. It is actually a component of the LCA. Measuring the amount of carbon dioxide emitted by manufacturing processes allows us to roughly gauge how much any individual polluter is contributing to atmospheric degradation, and in turn, climate change.

The food mile is a metric that measures the distance between the production source and the retail location, correlating distance traveled with energy consumption and pollution emissions. The longer food travels from its source to the grocery store or restaurant, the more gasoline is combusted, both consuming energy resources and emitting harmful pollutants.

All these measures are effective. Ultimately, it does not matter which analytic criteria is used in measuring the sustainability of a product or service, as long as this framework is employed consistently.

VALUES IN SUSTAINABLE SCM

To accurately gauge the desirability of implementing sustainability, we must understand the full spectrum of costs and values at stake. Sustainable corporations see market benefits such as increased sales from increased demand, increased prices from improvements in quality, reductions in operating costs from efficiencies, improved productivity, and avoided future costs in terms of environmental costs or damaged reputation. Nonmarket benefits are not experienced directly by the company, but also need to be considered. These nonmarket benefits include recreational uses of fishable, swimmable bodies of water, improvements in biodiversity, and greater life span and health on the part of the affected community.

The total value of a natural resource is a combination of three separate values: use value, option value, and existence value. Use value is the benefit derived from consumption or utilization of a resource. Option value and existence value are often termed “non-use” values as their benefits are not derived from actual use. Option value is value placed upon the ability to exercise the option in the future. It applies to irreplaceable resources with uncertain benefits: we value the ability to preserve the resource for future potential use. Existence value is the benefit people receive from knowing that a resource exists. Unlike the former two concepts of value, existence value is autonomous of human use or utility. For example, people place value on the very existence of a natural resource, such as Yellowstone Park, and seek to preserve it for its own sake. Concepts such as willingness-to-pay (WTP) for an environmental resource, or willingness-to-accept (WTA) compensation in exchange for giving up an environmental resource, are approximate indicators of the value stakeholders place on the environment affected by corporate activity. Managers should attempt to measure these values so as to include them in sustainable organizational behavior.

COST ASSESSMENT

Measurements of stakeholder preference are inherently uncertain, but approximations give managers at least a sense of the magnitude of the costs at stake. Monetizing external costs translates the impacts of corporate activity into terms that are commensurable with the internal motivators of corporate decisions. Monetization therefore allows firms to “see” the cost of their actions and, perhaps, internalize those costs. The two main models for monetizing environmental and social effects are cost-of-control and damage costing.

Cost-of-Control. Cost-of-control represents the cost of avoiding damages before they actually occur. If avoiding the damage imposes a cost on the corporation, then allowing the damage to occur could be understood as a value to the corporation. This approach effectively places a value on social or environmental damage by calculating the cost to avoid these damages. Consider the decision of whether to upgrade the lining in a waste storage container that holds toxic sludge from coal ash created by electricity generation. The environmental and social costs of such a leaking storage tank could involve (among other things) death of aquatic animal and plant life, loss of agricultural opportunities, and the carcinogenic contamination of drinking water. The monetary value of these items is extremely difficult to determine, especially since each depends upon unique circumstances and probabilities, and involves distinct forms of measurement. However, the cost of installing an adequate control technology, such as improved synthetic lining inside the storage tank, is easily determined. The cost-of-control method therefore allows simple and accurate calculations of the cost of decisions, without getting into technically challenging determinations of the full consequences of present decisions of future events.

A variation on the cost-of-control model is the shadow pricing model. This approach assumes governmental regulations reflect society's willingness to pay for sustainability performance and derives this amount from the cost of compliance with the regulation. This approach depends upon the governmental body correctly estimating the level of control society is willing to pay for. It may be true that society would pay much more for improved sustainability performance than what the regulations would suggest, especially when the regulations simply set a minimum safety threshold.

Damage Costing. Damage costing represents the cost of damages as if they had actually occurred. These cost calculations require significant amounts of data, time, and expense to perform accurately. Damage costing approximates the cost of social or environmental damage as an estimate of stakeholders' WTP to avoid the damage. In the coal ash storage tank example from above, consider how difficult it would be to determine the actual monetary cost of lost amphibious populations, or the slight increase in the probability that a few members of the surrounding community would get cancer. Determining actual costs can be very difficult endeavor and leaves the decision maker with considerable uncertainty. Stakeholders' WTP can be extrapolated from market price or appraisal if the resource is traded on an active market, and even the use of focus groups can help in its determination.

Costing Systems. Once a company has decided to strive for sustainable performance, it must include adequate costing systems to account for environmental costs. This can be done through activity-based costing, life-cycle costing, or full cost accounting. “Activity-based costing” seeks to avoid lumping together environmental costs with overhead or non-environmental costs. Disaggregating the amount spent on waste, for example, from the amount paid for buildings, allows managers to discover opportunities to improve sustainability performance. As a result, managers are able to identify the causal relationship between the activities that generate environmental consequences and the company's bottom line. Activity-based costing tries to uncover buried social and environmental costs and attribute them to the activities that cause them.

An alternative to activity-based costing is life-cycle costing, an extension of the life-cycle assessment of environmental impacts. “Life-cycle costing” is the amortized annual cost of a product (including capital and disposal costs), discounted over the life cycle of a product. Life-cycle costing requires the monetization of present and future costs and benefits of SCM activities. An alternative to both activity-based and life-cycle costing is full cost accounting, which seeks to incorporate the broadest set of external and future costs.

“Full cost accounting” incorporates the result of life-cycle costing into an accounting framework, which allows managers to base decisions such as product design or price on sustainability impacts. This framework incorporates internal, external, present and future costs and benefits.

Costing systems are important for SCM sustainability because they allow managers to identify areas that need both money savings and environmental performance improvements. Further, clearly articulated cost models allow managers to make optimal pricing decisions.

RISK ASSESSMENT

Managers must be able to identify and monetize potential risks and include them in return on investment and net-present-value determinations. An investment decision that fails to consider a risks assessment is unsound. The company may find the costs of mandatory responsibilities, including product take-back and site cleanup, to destroy the expected profits. Risk assessment requires attention to long-time horizons, as well as attention to low probability events. Sustainability problems pose high costs when they arise and there is a tendency to omit them as they often take a long time to manifest and they occur infrequently.

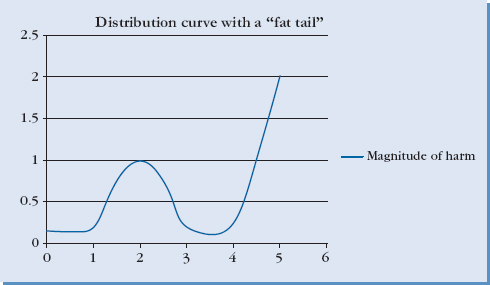

“Fat Tails”. Environmental crises can be understood statistically as “fat tails,” shown in Figure 13.6. If we look at a distribution curve with the probability of an event on the X-axis and the magnitude of the harm resulting from the event on the Y-axis, these events are called “fat tails” in that they are of low probability (they are many standard deviations away from the mean, at the tail of a distribution curve), yet of high consequence (they are called “fat” relative to the consequences of other issues).

FIGURE 13.6 “Fat tail” diagram.

Managers need tools for incorporating risks. These tools include scenario-based analysis, fuzzy logic, Monte Carlo simulations, and real option analysis. We look at these next.

Scenario-Based Analysis. Scenario-based analysis identifies issues and opportunities that may arise in various foreseeable circumstances. Royal Dutch Shell uses descriptive scenarios based on forecasting research to provide decision makers with rough sketches of possible future states of affairs to help them focus on long-term consequences of supply chain impacts. For example, different business scenarios could be envisioned by tweaking variables such as energy source, resource availability, or socioeconomic trends. What would the world look like if we could convert saltwater into energy? What if freshwater ran short? What if the middle class disappeared? How could companies survive in such scenarios? Scenario-based analyses are really thought experiments that bring critical issues into the foreground.

Fuzzy Logic. Fuzzy logic is a tool from mathematics that helps managers deal with sets of information that lack precise boundaries. Using the best estimate of the dollar amount required to cover foreseeable consequences, the best and worst case monetary values are estimated. Optimistic and pessimistic magnitudes are assigned a “degree of belief” between 0 and 1 to reflect their likelihood. Fuzzy logic associates the net present value of a decision with its degree of belief, which allows managers to see the range of situations that could give rise to future financial liability.

Monte Carlo Simulations. When managers must use a complex decision tree, Monte Carlo simulations can help compare the outcomes of one operation against another. The costs associated with environmental remediation depend on numerous contingencies, such as applicable environmental law and the effectiveness of remediation techniques. Monte Carlo simulations draw random samples from the cost-probability distribution for each variable (or option), and algorithmically choose the option of lowest foreseeable cost at each point in the decision tree. The process is performed by computer software that can determine the likelihood that one operation will cost more than another, or simply compare the likely costs of each option. Importantly, cost estimates are associated with confidence levels. The magnitude of a risk standing alone is almost meaningless: it must be associated with a probability of occurrence in order to be useful to a manager.

Real Option Analysis. Real option analysis helps to frame risk analysis decisions when static models are insufficient. Sometimes a small investment today that preserves an option can lead to a large return in the future when that option leads to a greater opportunity than was available before. Option assessment and option screenings help visualize reasonable available alternatives courses of conduct, including their relative costs and benefits. The basic concern is to determine whether to leave an option open for future managers to utilize in order to avoid environmental or social risks that happen to manifest. Option analysis also enables managers to optimize choices that involve numerous objectives, uncertainties, and constraints.

Risks can be social, political or environmental. “Social risks” arise from unmet community expectations, and include violence, riots, or economic devastation when monolithic commercial activity dissipates. “Political risks” arise when governmental influences compromise the company's economic value. Political risks are company-specific when a government targets a single organization for retribution, including the nationalization of an oil company or a state-sponsored terrorist attack on a manufacturing facility. Country-specific political risks include dramatic domestic civil strife, changes in currency value, or changes to the tax code. “Environmental risks” arise from unpredictable or uncontrollable risks stemming from geological activity (such as earthquakes or volcanoes) or meteorological activity (such as floods or hurricanes).

To make sustainable SCM decisions, risks must be identified and their monetary impact should be estimated. This allows managers to make better decisions with respect to the environment, human health and safety, and their company's financial bottom line.

SUSTAINABILITY IN PRACTICE

SCM has tremendous opportunity to impact sustainability given its cross-functional and cross-enterprise nature. Changes in SCM functions can have a major impact on sustainability. For example, the function of logistics is responsible for the movement and storage activities of the supply chain. These activities are among the most energy intensive. Carbon dioxide emissions from the transportation sector alone account for 33% of the United States' total CO2 emissions. Judicious consideration of modes of transportation and sourcing can dramatically impact sustainability. Just consider the differential between energy consumed to ship a New Zealand lamb chop to a restaurant in New York City, versus procuring a lamb chop from a farm in upstate New York. The same concerns could be raised with respect to sourcing fish from international waters and fruit from foreign producers. The savings in product price or the benefits of product quality may be outweighed by the environmental costs of logistics across large distances.

Many companies are aware of the impact of SCM on sustainability and are making significant changes. For example, in order to improve environmental performance in logistics, McDonald's has applied the concept of zero waste to delivery processes. In a clever innovation, McDonald's plans to convert the United Kingdom delivery vehicle fleet to run on biodiesel based on the same cooking oil used to make French fries. There are numerous examples such as these companies are making. We look at some of these changes next.

PRODUCT DESIGN

Innovations in product design can significantly improve environmental and social sustainability performance. Changes in product design affect use of material, sourcing, and disposal. Often companies are not aware that some of their components are harmful to the environment. For example, one of the most distinctive features of Nike shoes, aside from the dramatic swooping check that identifies the brand, is the air bubble in the heel of Nike Air basketball sneakers. However, the company only recently became aware that the pocket contained a gas known as sulphur hexafluoride, or SF6, which is actually a greenhouse gas. As part of Nike's sustainability initiative, Nike replaced SF6 with nitrogen, which breaks up more readily upon release, and is not a greenhouse gas. A small change such as this can have significant environmental impact.

Some environmentally friendly innovations in product design can actually transform the business model, as happened with Interface Inc., the world's largest carpet manufacturer. Originally, Interface was in the business of selling carpets to clients. When the carpet was worn out, Interface would replace the entire carpet. Now, Interface installs carpets in modular form, giving clients the opportunity to inspect carpet “tiles” for wear on a monthly basis, replacing only the tiles that are worn out. This transformation provides a savings to clients and is better for the environment as it requires less pollution and energy consumption than the original model of replacing the entire product.

Carbon Fiber Auto Parts

Replacing steel with carbon fiber can significantly reduce weight of automobile vehicles. Unfortunately, carbon fiber costs four times as much as steel by weight. However, an innovative technique for designing the product promises to cut costs of carbon fiber by 25% while reducing vehicle weight by as much as 20%. Carbon molecules are arranged in parallel, forming incredibly strong filaments, which are wound into strands and woven into a fabric, which is mixed with glue and hardened in molds to form car parts. The “knitting-yarn” carbon fiber breakthrough was developed by Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee, which persuaded a yarn factory in Lisbon, Portugal to allocate a portion of its plant to produce the new product. BMW AG is getting in on the auto-grade carbon fiber action as well. Because of the energy intensity required to convert the carbon fiber into fabric, BMW produces the product near a cheap hydroelectric power source in Spokane, Washington, then ships it to Germany where it is formed into car parts by partner SGL Carbon. BMW plans to use the carbon fiber as an interior shell for the MegaCity electric car to drop total weight by over 700 pounds.

Adapted from: Ramsey, Mike. “Technology that Breaks the Car Industry Mold.” The Wall Street Journal, January 6, 2011.

PACKAGING

Packaging offers an excellent opportunity to significantly impact the sustainability of a supply chain. For example, Proctor & Gamble (P&G) reduced the negative environmental consequences of product packaging by designing a toothpaste tube that can be shipped and displayed for retail without any paper packaging. Also, Nestlé Waters North America has created its Eco-Shape bottle that uses 25% less plastic compared to earlier bottles. Similarly, Nestlé decided to use smaller labels on the outside of their water bottles in order to save paper. In five years, the company saves an estimated 20 million pounds of paper. Product packaging is so important that even Wal-Mart has developed an environmental sustainability scorecard to evaluate product packaging used by its vendors. The criteria include GHG emissions from packaging production, product-to-packaging ratio, recycled packaging content, and emissions from transporting the packaging.

Product packaging can serve multiple purposes. It takes just a little bit of imagination to envision a further use for a package that would otherwise end up in a landfill. Innovations in use of product packaging can lead to considerable environmental and economic savings. For example, Stony-Field Farms, a dairy company famous for its “green” policies, has implemented a zero-waste concept that significantly reduces pollution. The company has a policy of take-back for the yogurt cups it sells. These plastic yogurt cups are then used to manufacture toothbrushes. Other companies use aluminium cans to make office furniture.

Companies can also work together in partnerships to take advantage of each other's talents in creating sustainable packaging. Consider India P&G, which decided to offer Pantene shampoo in single-serve packages for $0.02 each to low-income communities. The goal is to allow individuals at the very bottom of the economic pyramid to access product markets typically only available to consumers in developed countries. However, this creates the problem of disposing of packaging. Companies like Cargill and Dow Chemical are researching to develop biodegradable packages for these mini-products to avoid excess waste. Together, these innovations promote social and environmental sustainability.

SOURCING

Sourcing practices can dramatically impact sustainability. Selecting suppliers that follow sustainability practices—and finding ways to monitor their compliance— are a large issue for companies. Just consider the reputational problems Home Depot encountered from 1997 to 1999 when environmental groups organized protests against the company, charging it was failing to ensure that its wood didn't come from endangered forests. In response, Home Depot publicly promised that lumber supplies would no longer come from endangered forests, and even took affirmative steps to collaborate with environmental groups in Chile to protect such forests.

Improvements in sourcing do not have to be dramatic. Even incremental or piecemeal improvements in sourcing count for something. Instead of overhauling all products, Ben & Jerry's simply released a new product line called For A Change, which procures cocoa, vanilla, and coffee beans from farmers who participate in cooperative farmer's associations that ensure these farmers a fair price for their beans.

Deciding how to evaluate, select, and monitor suppliers is a critical task. A structured screening process can help companies choose suppliers who meet sustainability criteria. For example, Nike developed a New Source Approval Process to determine whether to acquire a new factory. The criteria include inspection results along environmental, safety, and health dimensions, as well as a third-party labor audit. This helps ensure company expansion is consistent with principles of environmental and social sustainability.

Some companies rely on contracting to mandate certain practices from their suppliers. In order to ensure compliance with labor standards, L'Oréal uses a supplier selection process that begins with contract language requiring compliance from suppliers and supplier subcontractors. L'Oréal enforces these social sustainability initiatives by monitoring compliance through surprise audits involving plant inspections, document review, and interviews with supplier employees. When audit results fail on a rated scale, L'Oréal takes necessary corrective measures.

Other companies rely on third-party audits to monitor sustainability compliance. For example, Unilever—the world's largest tea company—has committed to sustainable sourcing for all tea leaves. In collaboration with Rainforest Alliance, Unilever sees to it that all tea-growing estates are audited assuring sustainable growth and fair trade of the product. Like Unilever, Wal-Mart has partnered with an oversight organization to ensure sustainable sourcing. Wal-Mart plans to purchase all wild-caught seafood from sustainable fisheries certified by the Marine Stewardship Council. This helps prevent overfishing, as well as keep fish containing unhealthy toxins like mercury off the shelves.

In addition to selecting and monitoring supplier sustainability practices, some companies offer training programs to their suppliers to continue improving. Cadbury Schweppes offers a training program in pest control and labor management techniques to the 4,000 cocoa suppliers in Ghana through the Farmers' Field School. This is a win-win for the suppliers and Cadbury Schweppes: the farmers have improved labor conditions and Cadbury Schweppes has a more reliable cocoa supply.

PROCESS DESIGN

Redesign of organizational processes can go a long way toward improving the environmental and social sustainability of a supply chain. Consider Kingfisher—Europe's leading home-improvement retailer and third largest in the world—which uses an evaluation system that provides actions for each operating company to undertake in order to meet corporate sustainability policy. The program is called Steps to Responsible Growth with formal evaluations taking place two times each year to monitor progress. Similarly, the Swedish hotel chain Scandic Hotels (www.scandichotels.com), created the Resource Hunt program to incentivize employees to improve their use of resources to yield efficiency gains. Hotel employees receive a part of the savings from a reduction in energy and water consumption, as well reduction in waste. Through these measures Scandic Hotels was able to save over a million dollars over just a few years.

Process improvements that address disposal of equipment are an important part of sustainability. Technology equipment can contain environmentally damaging materials that are relatively impervious to natural biodegradation. Improper technology equipment disposal can pose serious environmental consequences. In light of this, Hewlett-Packard implemented a product end-of-life or “take back” procedure. This enabled Hewlett-Packard to recycle over 70,000 tons of computer products, which were then refurbished to be resold or donated. In one procedural move, Hewlett-Packard reduced environmentally damaging waste, increased profits by creating a secondary market for used equipment, and promoted social sustainability by donating computers.

MARKETING SUSTAINABILITY

Products frequently advertise their “green” features, such as their use of recycled materials, or that their packaging is biodegradable, or that they have entered into fair partnerships with international laborers, or the fact that the product does not contain ingredients which are harmful to the environment. Sustainable features are typically displayed through labels on the product itself. Sellers prominently display certifications by independent reviewers as to the genuinely sustainable nature of their product or manufacturing process. As long as consumers place a premium on the sustainability of products and services, advertising will cater to this preference. That is, as long as consumers prefer sustainable products, sellers have an incentive to market their products and services as sustainable, regardless of actual practices. However, without independent and objective evaluation as to the efficacy of the sustainability measures taken, products may be spuriously labeled “sustainable” when in fact they are not. Independent assessment of sustainability practices is important to counteract this “greenwashing” effect help consumers identify true sustainability measures.

UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES

Before any company goes headlong toward implementing a seemingly beneficial sustainability initiative, a holistic assessment of all foreseeable costs and benefits must be conducted. This should include predictable behavioral changes that a new policy may induce on the part of affected parties. For example, a rule that mandated a company to eliminate a certain type of pollutant from their plant emissions by a certain date, with no other conditions attached, would predictably encourage plant operators to emit as much of this pollutant as possible before the abatement deadline, causing spikes in emissions levels. A rule that prohibited managers from firing elderly employees without good cause could very well have the perverse effect of discouraging employers from hiring elderly employees in the first place. The tendency of good intentions to have unexpected and undesirable consequences requires sustainable SCM decisions to be made only after adequate reflection and analysis.

Consider the hazards to the environment that can occur even with the best of intentions. Suppose a corporation owns manufacturing plants all over the continent. They want to reduce overall pollutant emissions by 20% in order to protect the health of the environment. They decide to use an auction system to distribute emissions permits, so the permission to continue emitting pollutants goes to the highest bidders. Plants that can reduce emissions cheaply through technology or process innovations do so. Older plants that would require major modifications in order to comply with the emissions reduction find it more economically feasible to purchase the permits. This leads to an economically efficient allocation of emissions permits. However, suppose the plants that aggregated the most permits were all clustered in the same region. Suppose further that this region was home to many biologically rich ecosystems. The permit allocation auction may have reduced net pollution emissions by 20%, but it lead to a “hot spot” of highly concentrated pollutants in an area where such pollution could lead to devastating environmental costs. In this way an attempt at environmental sustainability could backfire with unintended consequences that end up compromising environmental goods.

The obstacles posed by the environmental and social risks of our world force managers to make decisions where the intuition hesitates and the data is uncertain. Unintended consequences in the context of sustainability initiatives highlight the importance of making well thought out and informed decisions even when managers have the best intentions.

CHAPTER HIGHLIGHTS

- The environmental and social initiatives that define the current trend toward sustainability can be effectively incorporated into organizational decision making by expanding the concepts of cost, value, and risk to include longer time horizons and the reactions of all stakeholders.

- The Supply Chain Sustainability Model can be used to enable managers to make effective sustainability decisions by linking inputs (external context, internal context, business context, human and financial resources), processes(leadership, strategy, structure, and systems), outputs (sustainability performance, stakeholder reactions), and outcomes (long-term corporate financial performance) in a feedback loop.

- Nine principles of sustainability performance are ethics, governance, transparency, business relationships, financial return, community involvement and economic development, values of products and services, employment practices, and protection of the environment.

- Quantifiable data relevant to costs, risks, and stakeholder preferences are needed in order to accurately measure and predict the impact of sustainability performance.

- Sustainability implementation requires a concerted effort from top leadership and cuts across all aspects of a supply chain. In other words, sustainability performance is a serious endeavor that requires considerable commitment of corporate assets and attention.

KEY TERMS

- Sustainability

- Financial payoffs

- Customer-related payoffs

- Operational payoffs

- Organizational payoffs

- Environmental sustainability

- Social sustainability

- Crisis-oriented

- Cost-oriented

- Design standard

- Performance standard

- Minimalist ethic

- Reasonable care ethic

- Good works ethic

- External context

- Internal context

- Business contexts

- Human and financial resources

- Leadership

- Proactive sustainability actions

- Reactive sustainability actions

- Internal sustainability actions

- External sustainability actions

- Sustainability performance

- Feedback loops

- Compliance

- Total cost of ownership (TCO)

- Life-cycle assessment (LCA)

- Ecological footprint

- Carbon footprint

- Food mile

- Use value

- Option value

- Existence value

- Cost-of-control

- Shadow pricing

- Damage costing

- Activity-based costing

- Life-cycle costing

- Full cost accounting

- Scenario-based analysis

- Fuzzy logic

- Social risks

- Political risks

- Environmental risks

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- What economic arguments can be made for and against environmental sustainability initiatives? What economic arguments can be made for and against social sustainability initiatives? What personal choices have you made as a consumer with respect to environmental or social sustainability?