Chapter 1. Introducing Swift in depth

In this chapter

- A brief overview of Swift’s popularity and supported platforms

- The benefits of Swift

- A closer look at Swift’s subtle downsides

- What we will learn in this book

It is no secret that Swift is supported on many platforms, such as Apple’s iOS, macOS, watchOS, and tvOS. Swift is open source and also runs on Linux, and it’s gaining popularity on the server side with web frameworks such as Vapor, Perfect, Zewo, and IBM’s Kitura.

On top of that, Swift is slowly not only encompassing application programming (software for users) but also starting to enter systems programming (software for systems), such as SwiftNIO or command-line tools. Swift is maturing into a multi-platform language. By learning Swift, many doors open to you.

Swift was the most popular language on Stack overflow in 2015 and remains in the top five most-loved languages in 2017. In 2018, Swift bumped to number 6 (https://insights.stackoverflow.com/survey/2018).

Swift is clearly here to stay, and whether you love to create apps, web services, or other programs, I aim for you to get as much value as possible out of this book for both yourself and any team you’re on.

What I love about Swift is that it’s easy to learn, yet hard to master. There’s always more to learn! One of the reasons is that Swift embraces many programming paradigms, allowing you to pick a suitable solution to a programming problem, which you’re going to explore in this book.

1.1. The sweet spot of Swift

One thing I love about a dynamic language—such as Ruby—is its expressive nature. Your code tells you what you want to achieve without getting too much in the way of memory management and low-level technology. Writing in Ruby one day, and Objective-C the other, made me believe that I either had to pick between a compiled language that performed well or an expressive, dynamic language at the cost of lower performance.

Then Swift came out and broke this fallacy. Swift finds the right balance where it shares many benefits of dynamic languages—such as Ruby or Python—by offering a friendly syntax and strong polymorphism. Still, Swift avoids some of the downsides of dynamic languages, most notably the performance, because Swift compiles to native machine code via the LLVM compiler. Because Swift is compiled via LLVM, you get not only high performance, but also tons of safety checks, optimizations, and the guarantee that your code is okay before even running it. At the same time, Swift reads like an expressive dynamic language, making it pleasant to work with and effortless to express your intent.

Swift can’t stop you from writing bugs or poor code, but it does help reduce program errors at compile time using various techniques, including, but not limited to, static typing and strong support for algebraic data types (enums, structs, and tuples). Swift also prevents null errors thanks to optionals.

A downside of some static languages is that you always need to define the types. Swift makes this easier via type inference and can deduce concrete types when it makes sense. This way, you don’t need to explicitly spell out every single variable, constant, and generic.

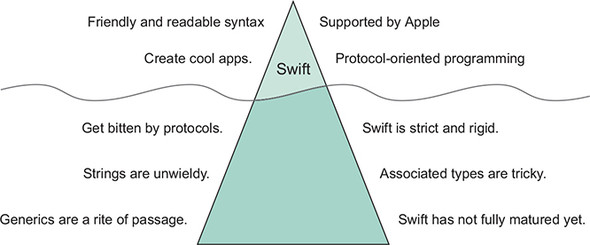

Swift is a mixtape of different programming paradigms, because whether you take an object-oriented approach, functional programming approach, or are used to working with abstract code, Swift offers it all. As the major selling point, Swift has a robust system when it comes down to polymorphism, in the shape of generics and protocol-oriented programming, which gets pushed hard as a marketing tool, both by Apple and developers (see figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. The sweet spot of Swift

1.2. Below the surface

Even though Swift reels you in with its friendly syntax and promises to build amazing apps, it’s merely the tip of the iceberg. An enticing entry to learning Swift is to start with iOS development, because not only will you learn about Swift, you will also learn how to create beautiful apps that are composed of crucial components from Apple frameworks.

But as soon as you need to deliver components yourself and start building more elaborate systems and frameworks, you will learn that Swift works hard to hide many complexities—and does so successfully. When you need to learn these complexities, and you will, Swift’s difficulty curve goes up exponentially. Even the most experienced developers are still learning new Swift tricks and tidbits every day!

Once Swift has you hooked, you’ll likely hit speed bumps in the shape of generics and associated types, and something as “simple” as handling strings may cause more trouble than you might expect (see figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. The tip of Swift’s iceberg

This book shines in helping you handle the most common complexities. You will cover and tackle any issues and shortcomings with Swift, and you’ll be able to wield the powers that these complexities bring while having fun doing so.

1.3. Swift’s downsides

Swift is my favorite programming language, but let’s not look at it through rose-tinted glasses. Once you acknowledge both Swift’s strong and weak points, you can adequately decide when and how you’d like to use it.

1.3.1. ABI stability

Swift is still moving fast and is not ABI-stable, which means that code written in Swift 4 will not be compatible with Swift 5, and vice versa. Imagine writing a framework for your application. As soon as Swift 5 comes out, an application written in Swift 5 can’t use your framework until you’ve updated your framework to Swift 5. Luckily, Xcode offers plenty of help to migrate, so I expect that this migration won’t be as painful.

1.3.2. Strictness

Swift is a strict and rigid language, which is a common criticism of static languages but even more so when working with Swift. Before getting comfortable with Swift, you may feel like you’re typing with handcuffs on. In practice, you have to resolve many types at compile-time, such as using optionals, mixing values in collections, or handling enums.

I would argue that Swift’s strict nature is one of its strong selling points. As soon as you try to compile, you learn of code that isn’t working as opposed to having a customer run into a runtime error. Once you’ve made the initial investment to get comfortable with Swift, it will come naturally, and its restrictiveness will stop you less. This book helps you get over the hump, so that Swift becomes second nature.

1.3.3. Protocols are tricky

Protocols are the big selling point of Swift. But once you start working with protocols, you will hit sharp edges and cut yourself from time to time. Things that “should just work” somehow don’t. Protocols are great in their current state and already good enough for creating quality software, but sometimes you hit a wall, and you’ll have to use workarounds—of which this book shares plenty.

A common source of frustration: if you’d like to pass Equatable types to a function to see if they are equal, you get stopped. For instance, you might naively try checking if one value is equal to everything inside an array, as shown in the next listing. You will learn that this won’t fly in Swift.

Listing 1.1. Trying to equate to types

areAllEqual(value: 2, values: [3,3,3,3])

func areAllEqual(value: Equatable, values: [Equatable]) -> Bool {

guard !values.isEmpty else { return false }

for element in values {

if element != value {

return false

}

}

return true

}

Swift returns a cryptic error with a vague suggestion on what to do:

error: protocol 'Equatable' can only be used as a generic constraint because it has Self or associated type requirements

You’ll see why this happens and how to avoid these issues in chapters 7 and 8.

Swift’s protocol extensions are another of its major selling points and are one of the most powerful features it has to offer. Protocols can act like interfaces; protocol extensions offer default implementations to types, helping you avoid rigid subclassing trees.

Protocols, however, are trickier than they may seem and may surprise even the seasoned developer. For instance, let’s say you have a protocol called FlavorType representing a food or drink item that you can improve with flavor, such as coffee. If you extend this protocol with a default implementation that is not found inside the protocol declaration, you may get surprising results! Notice in the next listing how you have two Coffee types, yet they both yield different results when calling addFlavor on them. It’s a subtle but significant detail.

Listing 1.2. Protocols can surprise us

protocol FlavorType{

// func addFlavor() // You get different results if this method doesn't exist.

}

extension FlavorType {

func addFlavor() { // Create a default implementation.

print("Adding salt!")

}

}

struct Coffee: FlavorType {

func addFlavor() { // Coffee supplies its own implementation.

print("Adding cocoa powder")

}

}

let tastyCoffee: Coffee = Coffee() // tastyCoffee is of type 'Coffee'

tastyCoffee.addFlavor() // Adding cocoa powder

let grossCoffee: FlavorType = tastyCoffee // grossCoffee is of type FlavorType

grossCoffee.addFlavor() // Adding salt!

Even though you’re dealing with the same coffee type, first you add cocoa powder, and then you accidentally add salt, which doesn’t help anyone get up in the morning. As powerful as protocols are, they can introduce subtle bugs sometimes.

1.3.4. Concurrency

Our computers and devices are concurrent machines, utilizing multiple CPUs simultaneously. When working in Swift you are already able to express concurrent code via Apple’s Grand Central Dispatch (GCD). But concurrency doesn’t exist in Swift as a language feature.

Because you can already use GCD, it’s not that big of a problem to wait a bit longer on a fitting concurrency model. Still, GCD in combination with Swift is not spotless.

First, working with GCD can create a so-called pyramid of doom—also known as deeply nested code—as showcased by a bit of unfinished code in the following listing.

Listing 1.3. A pyramid of doom

func loadMessages(completion: (result: [Message], error: Error?) -> Void) {

loadResource("/user") { user, error in

guard let data = data else {

completion(nil, error)

return

}

loadResource("/messages/", user.id) { messages, error in

guard let messages = messages else {

completion(nil, error)

return

}

storeMessages(messages) { didSucceed, error in

guard let error != nil else

{

completion(nil, error)

return

}

DispatchQueue.main.async { // Move code back to main queue

completion(messages)

}

}

}

}

}

Second, you don’t know on which queue asynchronous code gets called. If you were to call loadMessages, you could be in trouble if a small change moves the completion block to a background queue. You may be extra cautious and complete the callback on the main queue at the call site, but either way, there is a compromise.

Third, the error handling is suboptimal and doesn’t fit the Swift model. Both the returned data and error can theoretically be filled or nil. The code doesn’t express that it can only be one or the other. We cover this in chapter 11.

You can expect an async/await model in Swift later, perhaps version 7 or 8, which means a wait until these issues get solved. Luckily, GCD is more than enough for most of your needs, and you may find yourself turning to RxSwift as a reactive programming alternative.

1.3.5. Venturing away from Apple’s platforms

Swift is breaking into new territory for the web and as a systems language, most notably with its support of IBM in the shape of the web server Kitura and in bringing Swift to the cloud. Moving away from Apple’s platforms offers exciting opportunities, but be aware that you may find a lack of packages to help you out. For the xOS frameworks, such as iOS, watchOS, tvOS, and macOS, you can use CocoaPods or Carthage to handle your dependencies; outside of the xOS family, you can use the Swift Package Manager, offered by Apple. Many Swift developers are focused on iOS, however, and you may run into an alluring package with a lack of support for the Swift Package Manager.

Although it’s hard to match existing ecosystems, such as thousands of Python’s packages, npm from Node.js, and Ruby gems, it also depends on your perspective. A lack of packages can also be a signal that you can contribute to the community and ecosystem while learning Swift along the way.

Even though Swift is open source, Apple is holding the wheel. You don’t have to worry about Apple stopping support of Swift, but you may not always agree with the direction or speed of Swift’s updates. You still have to depend on third-party tools to get dependencies working for iOS and macOS, and Xcode doesn’t yet integrate well with the Swift Package Manager; unfortunately, both issues appear to be a low priority for Apple.

1.3.6. Compile times

Swift is a high-performing language. But the compilation process can be quite slow and suck up plenty of developer time. Swift is compiled into multiple steps via the LLVM compiler. Although this gives you optimizations when you run your code, in day-to-day programming you may run into slow build times, which can be a bit tedious if you’re trying to quickly test a running piece of code. Not every Swift project is a single project, either; as soon as you incorporate multiple frameworks, you’ll be compiling a lot of code to create a build, slowing down your process.

In the end, every programming language has pros and cons—it’s a matter of picking the right tool for the job. I believe that Swift has a bright future ahead to help you create beautiful software with clean, succinct, and high-performing code!

1.4. What you will learn in this book

This book aims to show you how to solve problems in elegant ways while applying best practices.

Even though this book has Swift on the cover, I think one of its strong points is that you’ll learn concepts that seamlessly transfer to other languages.

You’ll learn

- Functional programming concepts, such as reduce, flatMap, Optional, and Result, but also how to think in algebraic data types with structs, tuples, and enums

- Many real-world scenarios that you approach from different angles while considering the pros and cons of each approach

- Generics, covering compile-time polymorphism

- How to write more robust, concise, easy-to-read code

- Protocol-oriented programming, including thoroughly understanding associated types, which are considered the hardest part of protocols

- How Swift works at runtime and compile-time via the use of generics, enums, and protocols

- How to make trade-offs in functional programming, object-oriented programming, and protocol-oriented programming

At the end of this book, your tool belt will be heavy from all the options you have to tackle programming problems. After you internalize these concepts, you may find that learning other languages—such as Kotlin, Rust, and others that share similar ideas and functionality—is much easier.

1.5. How to make the most of this book

An excellent way to learn a programming language is to do exercises before reading a chapter. Be honest and see if you can truly finish them, as opposed to glancing over them and thinking you already know the answer. Some exercises may have some tricky situations hidden in there, and you will see it once you start working on them.

After doing the exercises for a chapter, decide if you want to read the chapter to learn new matter.

This book does have a flow that amps up the difficulty the further you read. Still, the book is set up in a modular way. Reading the chapters out of order is okay.

1.6. Minimum qualifications

This is not an absolute beginner’s book; it assumes that you have worked a bit with Swift before.

If you consider yourself an advanced beginner or at intermediate level, most chapters will be valuable to you. If you consider yourself an experienced developer, I still believe many chapters are good to fill in your knowledge gaps. Because of this book’s modularity, you can pick and choose the chapters you’d like to read without having to read earlier chapters.

1.7. Swift version

This book is written for Swift version 4.2. All the examples will run on that version either in the command line, or in combination with Xcode 10.

Summary

- Swift is supported on many platforms.

- Swift is frequently used for iOS, watchOS, tvOS, and macOS development and more and more every day for web development, systems programming, command-line tools, and even machine learning.

- Swift walks a fine line between high performance, readability, and compile-time safety.

- Swift is easy to learn but hard to master.

- Swift is a safe and high-performing language.

- Swift does not have built-in concurrency support.

- Swift’s Package Manager doesn’t work yet for iOS, watchOS, tvOS, or macOS.

- Swift entails multiple programming styles, such as functional programming, object-oriented programming, and protocol programming.