Suppose somebody new joins your little Mac family—a new worker, student, or love interest, for example. And you want to make that person feel at home on your Mac.

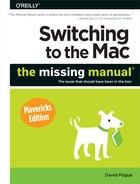

Begin by opening System Preferences (Chapter 16). In the System Preferences window, click Users & Groups (which used to be called Accounts). You have just arrived at the master control center for account creation and management (Figure 14-2).

To create a new account, start by unlocking the Users & Groups panel. That is, click the ![]() at lower left, and fill in your own account name and password.

at lower left, and fill in your own account name and password.

Now you can click the ![]() button beneath the list of accounts. The little panel shown at bottom in Figure 14-2 appears.

button beneath the list of accounts. The little panel shown at bottom in Figure 14-2 appears.

As though this business of accounts and passwords wasn’t complicated enough already, OS X offers several types of accounts. And you’re expected to specify which type each person gets at the moment you create an account.

To do that, open the New Account pop-up menu (Figure 14-2, bottom). Its five account types are described on the following pages.

If this is your own personal Mac, then just beneath your name on the Users & Groups pane of System Preferences, it probably says Admin. This, as you could probably guess, stands for Administrator.

Because you’re the person who originally installed OS X, the Mac assumes that you are its administrator—the technical wizard in charge of it. You’re the teacher, the parent, the resident guru. You’re the one who will maintain this Mac. Only an administrator is allowed to do the following:

Figure 14-2. Top: The screen lists everyone who has an account. From here, you can create new accounts or change passwords. If you’re new at this, there’s probably just one account listed here: yours. This is the account OS X created when you first installed it. You, the all-wise administrator, have to click the ![]() to authenticate yourself before you can start making changes. Bottom: In the account-creation process, the first step is choosing which type of account you want to create.

to authenticate yourself before you can start making changes. Bottom: In the account-creation process, the first step is choosing which type of account you want to create.

Install new programs into the Applications folder.

Add fonts that everybody can use.

Make changes to certain System Preferences panes (including Network, Date & Time, Energy Saver, and Startup Disk).

Use some features of the Disk Utility program.

Create, move, or delete folders outside of your Home folder.

Decide who gets to have accounts on the Mac.

Open, change, or delete anyone else’s files.

Bypass FileVault using a recovery key (FileVault).

The administrator concept may be new to you, but it’s an important pill to swallow. For one thing, you’ll find certain settings all over OS X that you can change only if you’re an administrator—including many in the Users & Groups pane itself. For another thing, administrator status plays an enormous role when you want to network your Mac to other kinds of computers, as described in the next chapter. And, finally, in the bigger picture, the fact that the Mac has an industrial-strength accounts system, just like traditional Unix and recent Windows operating systems, gives it a fighting chance in the corporations of America.

As you create accounts for other people who’ll use this Mac, you’re offered the opportunity to make each one an administrator just like you. Needless to say, use discretion. Bestow these powers only upon people as responsible and technically masterful as yourself.

Most people, on most Macs, are ordinary Standard account holders. These people have everyday access to their own Home folders and to the harmless panes of System Preferences, but most other areas of the Mac are off limits. OS X won’t even let them create new folders on the main hard drive, except inside their own Home folders (or in the Shared folder described starting on Sharing Across Accounts).

A few of the System Preferences panels display a padlock icon (![]() ). If you’re a Standard account holder, you can’t make changes to these settings without the assistance of an administrator. Fortunately, you aren’t required to log out so that an administrator can log in and make changes. You can just call the administrator over, click the padlock icon, and let him type in his name and password (if, indeed, he feels comfortable with you making the changes you’re about to make).

). If you’re a Standard account holder, you can’t make changes to these settings without the assistance of an administrator. Fortunately, you aren’t required to log out so that an administrator can log in and make changes. You can just call the administrator over, click the padlock icon, and let him type in his name and password (if, indeed, he feels comfortable with you making the changes you’re about to make).

A Managed account is the same thing as a Standard account—except that you’ve turned on Parental Controls. (These controls are described later in this chapter.) You can turn a Managed account into a Standard account just by turning off Parental Controls, and vice versa.

That is, this account usually has even fewer freedoms—because you’ve limited the programs this person is allowed to use, for example. Use a Managed account for children or anyone else who needs a Mac with rubber walls.

This kind of account is extremely useful—if your Mac is on a network (Chapter 15).

See, ordinarily, you can log in and access the files on your Mac in either of two ways:

In person, seated in front of it.

From across the network.

This arrangement was designed with families and schools in mind: lots of people sharing a single Mac.

This setup gets a little silly, though, when the people on a home or office network each have their own computers. If you wanted your spouse or your sales director to be able to grab some files from you, you’d have to create full-blown accounts for them on your Mac, complete with utterly unnecessary Home folders they’d never use.

That’s why the Sharing Only account is such a great idea. It’s available only from across the network. You can’t get into it by sitting down at the Mac itself—it has no Home folder!

Finally, of course, a Sharing Only account holder can’t make any changes to the Mac’s settings or programs. (And since they don’t have Home folders, you also can’t turn on FileVault for these accounts.)

In other words, a Sharing Only account exists solely for the purpose of file sharing on the network, and people can enter their names and passwords only from other Macs.

Once you’ve set up this kind of account, all the file-sharing and screen-sharing goodies described in Chapter 15 become available.

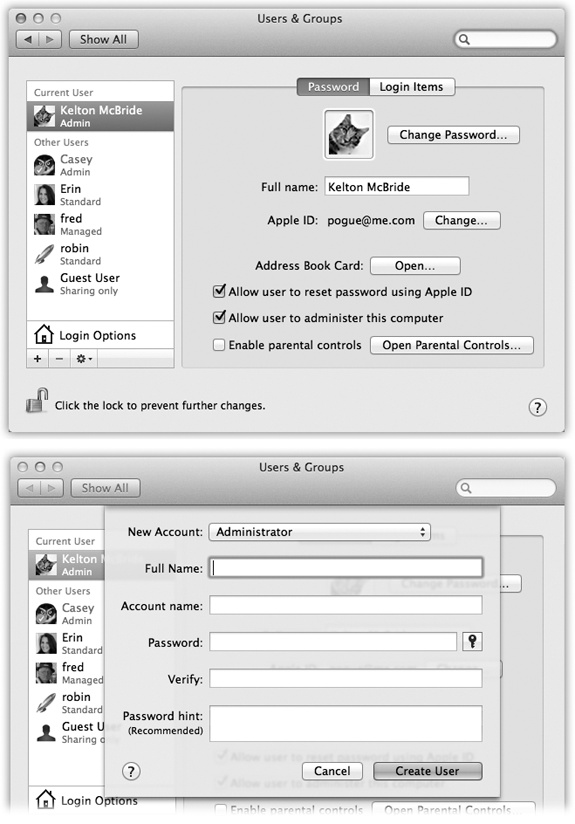

A group is just a virtual container that holds the names of other account holders. You might create one for your most trusted colleagues, another for those rambunctious kids, and so on—all in the name of streamlining the file-sharing privileges feature described on Sharing Any Folder. The box on Creating Groups covers groups in more detail.

The Guest account is great for accommodating visitors, buddies, or anyone else who’s just passing through and wants to use your Mac for a while. If you let such people use the Guest account, your own account remains private and un-messed-with.

Note

The Guest account isn’t listed among the account types in the New Account pop-up menu (Figure 14-2). That’s because there’s only one Guest account; you can’t actually create additional ones.

But it’s still an account type with specific characteristics. It’s sitting right there in the list of accounts from Day One.

Any changes your guest makes while using your Mac are automatically erased when she logs out. Files are deleted, email is nuked, setting changes are forgotten.

As noted above, the Guest account is permanently listed in the Users & Groups panel of System Preferences. Ordinarily, though, you don’t see it in the login screen list; if you’re normally the only person who uses this Mac, you don’t need to have it staring you in the face every day.

So to use the Guest account, bring it to life by turning on “Allow guests to log into this computer.” You can even turn on the parental controls described earlier in this chapter by clicking Open Parental Controls, or permit the guest to exchange files with your Mac from across the network (Chapter 15) by turning on “Allow guests to connect to shared folders.”

Just remember to warn your vagabond friend that once he logs out (and acknowledges the warning), all traces of his visit are wiped out forever.

At least from your Mac.

All right. So you clicked the ![]() button. And from the New Account pop-up menu, you chose the type of account you wanted to create.

button. And from the New Account pop-up menu, you chose the type of account you wanted to create.

Now, on the same starter sheet, it’s time to fill in the most critical information about the new account holder:

Name. If it’s just the family, this could be “Chris” or “Robin.” If it’s a corporation or school, you probably want to use both first and last names.

Account Name. You’ll quickly discover the value of this Account Name, particularly if your name is, say, Alexandra Stephanopoulos. Before Lion, it was called the short name; it’s meant to be an abbreviation of your actual name.

When you sign into your Mac in person, you can use either your full name or account (short) name. But when you access this Mac by dialing into it or connecting from across the network (as described in the next chapter), the short version is more convenient.

As soon as you tab into this field, the Mac proposes a short name for you. You can replace the suggestion with whatever you like. Technically, it doesn’t even have to be shorter than the “long” name, but spaces and most punctuation marks are forbidden.

Password, Verify. Here’s where you type this new account holder’s password (Figure 14-2). In fact, you’re supposed to type it twice, to make sure you didn’t introduce a typo the first time. (The Mac displays only dots as you type, to guard against the possibility that somebody is watching over your shoulder.)

The usual computer book takes this opportunity to stress the importance of a long, complex password—a phrase that isn’t in the dictionary, something that’s made up of mixed letters and numbers. This is excellent advice if you create sensitive documents and work in a big corporation.

But if you share the Mac only with a spouse or a few trusted colleagues in a small office, you may have nothing to hide. You may see the multiple-users feature more as a convenience (keeping your settings and files separate) than a protector of secrecy and security. In these situations, there’s no particular urgency to the mission of thwarting the world’s hackers with a convoluted password.

In that case, you may want to consider setting up no password—leaving both password blanks empty. Later, whenever you’re asked for your password, just leave the Password box blank. You’ll be able to log in that much faster each day.

Tip

Actually, having some password comes in handy if you share files on the network, because Mac A can store your name and password from Mac B—and therefore you can access Mac B without entering your name and password at all. So consider making your password something very short and easy, like the apostrophe/quote mark—the ′ key. It’s a real password, so it’s enough for Mac A to memorize. Yet when you are asked to enter your password—for example, when you’re installing a new program—it’s incredibly fast and easy to enter, because it’s right next to the Return key.

Password Hint. If your password is the middle name of the first person who ever kissed you, for example, your hint might be “middle name of the first person who ever kissed me.”

Later, if you forget your password, the Mac will show you this cue to jog your memory.

When you finish setting up these essential items, click Create User. If you left the password boxes empty, the Mac asks for reassurance that you know what you’re doing; click OK.

You then return to the Users & Groups pane, where you see the new account name in the list at the left side.

Here, three final decisions await your wisdom:

Apple ID. Since the Apple ID (DVD Player) is growing in importance and features—App Store, iTunes Store, email address, Web site, iCloud, syncing, Back to My Mac, and so on—it’s convenient to associate each account with its own Apple ID.

Allow user to administer this computer. This checkbox lets you turn ordinary, unsuspecting Standard or Managed accounts into Administrator accounts, as described above. You know—when your kid turns 18.

Enable Parental Controls. Parental Controls refers to the feature that limits what your offspring are allowed to do on this computer—and how much time a day they’re allowed to spend glued to the mouse. Details are on Parental Controls.

The usual sign-in screen (Figure 14-1) displays each account holder’s name, accompanied by a little picture.

When you click the sample photo, you get a pop-up menu of Apple-supplied graphics; you can choose one to represent you. It becomes not only your icon on the sign-in screen, but also your “card” photo in the Contacts program and your icon in Messages.

If you’d rather supply your own graphics file—a digital photo of your own head, for example—then choose Edit Picture from the pop-up menu. As shown in Figure 14-3, you have several options:

Drag a graphics file directly into the “picture well” (Figure 14-3). Use the cropping slider below the picture to frame it properly.

Click Choose. You’re shown a list of what’s on your hard drive. Find and double-click the image you want.

Take a new picture. If your Mac has a built-in camera above the screen, or if you have an external Webcam or a camcorder hooked up, then click the little camera button. The Mac counts down from 3 with loud beeps to help you get ready, and then takes the picture.

Figure 14-3. Once you’ve selected a photo to represent yourself (left), you can adjust its position relative to the square “frame” (right), or adjust its size by dragging the slider. Finally, when the picture looks correctly framed, click Set. (The next time you return to the Images dialog box, you can recall the new image using the Recent Pictures pop-up menu.)

In each case, click Set to enshrine your icon forever (or until you feel like picking a different one).

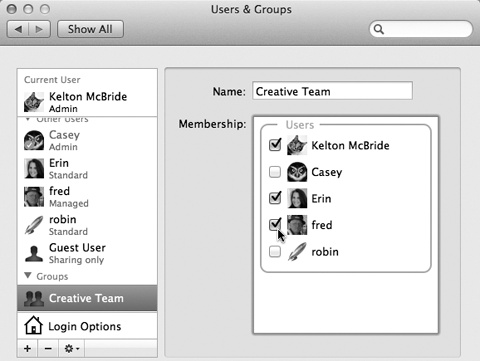

There’s one additional setting that your account holders can set up for themselves: which programs or documents open automatically upon login. (This is one decision an administrator can’t make for other people. It’s available only to whoever is logged in at the moment.)

To choose your own crew of self-starters, open System Preferences and click Users & Groups. Click your account. Click the Login Items tab. As shown in Figure 14-4, you can now build a list of programs, documents, disks, and other goodies that automatically launch each time you log in. You can even turn on the Hide checkbox for each one so that the program is running in the background at login time, waiting to be called into service with a quick click.

Figure 14-4. You can add any icon to the list of things you want to start up automatically. Click the ![]() button to summon the Open dialog box, where you can find the icon, select it, and then click Choose. Better yet, if you can see the icon in a folder or disk window (or on the desktop), just drag it into this list. To remove an item, click it in the list and then click the

button to summon the Open dialog box, where you can find the icon, select it, and then click Choose. Better yet, if you can see the icon in a folder or disk window (or on the desktop), just drag it into this list. To remove an item, click it in the list and then click the ![]() button.

button.

Don’t feel obligated to limit this list to programs and documents, by the way. Disks, folders, servers on the network, and other fun icons can also be startup items, so that their windows are open and waiting when you arrive at the Mac each morning.