Implementing Systems Thinking

Whether you are just learning systems thinking or you are in a position to train others on the subject, you will find endless opportunities to learn and apply the principles of systems thinking in all aspects of your work and personal life. Over the next several pages, the steps to learning how to think systemically will be described. You will also have the opportunity to read actual case studies in the training area and decide where the most effective intervention should be made.

Step 1: Stating the Problem

Issues and problems are all around us, all the time. We normally do not have to look too far to find them, and sometimes they even find us! Think about a problem or issue that you are dealing with and state it as clearly and succinctly as you can. This is the first step in learning to think systemically. Here are some examples:

- An employee is consistently late to work.

- One-third of the sales force cannot effectively close a deal.

- Low course evaluations for one particular instructor drop even further.

- The training manager is into turf building.

- Too many people expend too much energy “putting out fires.”

- A marketing employee just turned away an ordering customer because “that is the salesperson’s job.”

Clearly stating a problem goes a long way to help you focus on a potential solution. The next step is to expand on the problem as you have stated it. The best way to do this is to come up with the events or story behind the problem.

Step 2: Telling the Story

As an example for how to uncover a story, we will use one of the hypothetical problem statements listed above: “The training manager is into turf building.” Two years ago, Michael had been hired as the manager of employee training and development for a 7,000-person telecommunications organization. In addition to the employee training and development manager, there are two other positions in the training department: a manager of sales training and a manager of technical training.

As one of their responsibilities, each manager had to submit a budget to the director of education; these budgets were based on the projected costs to operate their respective programs. Included in each budget was a line item designated for educational supplies and resources, but the dollar amount was allocated across the entire training department.

From the start, Michael worked to protect his turf. Regardless of what other training programs were offered by the other managers, he decided on the training programs he wanted for “his people,” and publicly announced that he didn’t “care what the other trainers were doing.” He also wanted to make sure that he was the first person to secure common resources for his own programs—ordering books, journals, videotapes, and software.

Over time, Michael’s behavior led to a duplication of programs, increased costs, and a decrease in the overall effectiveness of training as measured by the organization’s 360-degree evaluations. In the process, Michael found himself becoming isolated from decisions, from his peers, and from social events. When anyone tells a story, you begin to sense the following:

- A Cause-and-Effect Flow to the Story

The cause and effect results are readily apparent in the sample case. Michael is the first to put his requests in for supplies; there is now less money in the budget for others to use. Because Michael does not care that he is running a management development course in addition to the one being run by the Sales Training Department, there is a duplication of effort. - Emergence of Certain Key Variables

These key variables or tangible components reveal the impact of the story as it is unfolding. For example, Michael’s actions constitute one variable; the decrease in effectiveness of the training is another variable. - Affinity Amid Components of the Problem

This shows how a decision that is made affects other parts of the same department or the organization as a whole. The actions taken and behavior displayed by Michael are detrimental to both the Training Department and the whole organization.

Step 3: Identifying the Key Variables

Variables are those components in the story that change over time. There is also an inherent relationship between these variables. You will want to choose only those variables that are relevant to your story. Using the turf-builder example from above, you can identify these other variables:

- manager’s decisions and actions

- duplication of training programs offered

- costs

- effectiveness of training

- training department budget

- isolation

When these key variables from the turf-builder scenario are put together, they tell the story of what transpired. There are two things to remember when selecting variables:

- They can have both quantitative and qualitative descriptors.

- Use nouns instead of verbs: for example, “Level of spending” instead of “Increasing costs deprives other departments.”

Step 4: Visualizing the Problem

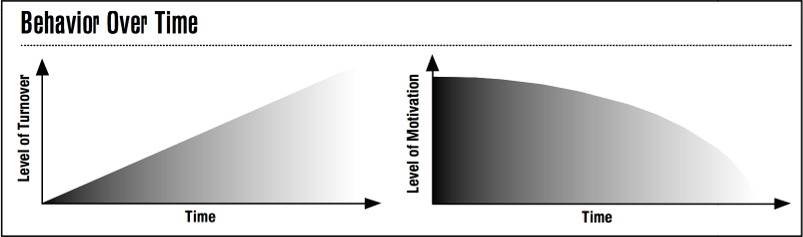

The old adage that a picture is worth a thousand words is exactly what this step produces. By taking the key variables identified above, we can create a visual graph of the existing problem. This, in a glance, will capture the pattern of the problem behavior over time. Appropriately, it is referred to as a behavior over time graph. The benefit of drawing a behavior over time graph is that it allows you to quickly view the main dynamics of the problem and how it changes over time. If a variable increases, decreases, or remains the same, even after implementing an intervention, you will be able to detect the change.

The actual creation of a behavior over time graph is fairly simple. On the horizontal axis is time, and on the vertical axis is the key variable that you are concerned with. The graph shown on the left enables you to visualize the turf-building example discussed above.

Step 5: Creating the Loops

In this step, we take our story and draw it as a causal loop diagram. A causal loop diagram illustrates which factors influence other factors. When a story is illustrated in this manner, we can begin to understand the underlying dynamics of the situation and, equally important, determine the most effective point at which to make an intervention. There are two types of causal loops: reinforcing loops and balancing loops. Let’s take a look at what each one means.

Reinforcing Loops

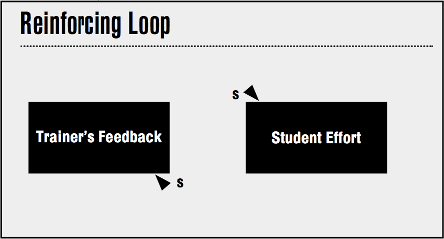

Reinforcing loops can be seen as akin to a self-fulfilling prophecy, in which one action, either positive or negative, influences another action. For example, you have noticed a direct link between a trainer’s positive feedback and the amount of effort expended by the student. In other words, the more positive feedback the trainer gives to the student, the more effort he or she puts into the class. A causal loop diagram would look like the figure in Reinforcing Loop, seen at left.

Reading the Loop: The loop indicates that as the trainer’s positive feedback increases, the student’s effort increases. As it happens in this case, the student’s effort also increases, and that in turn feeds back to influence or increase the trainer’s positive feedback. And the loop then becomes a self-perpetuating dynamic.

Take note of these special factors regarding reinforcing loops:

- Just as reinforcing loops can travel in a positive direction, they can also reverse into the negative direction. Try to read the loop again as if the trainer were withholding feedback or not providing any at all.

- The arrowhead connecting the two variables— trainer’s feedback and student effort—is called a “link.”

- When you see an arrowhead with an s near it, this indicates that there is a change occurring in the same direction.

- When you see an arrowhead with an o near it, this indicates that there is a change occurring in the opposite direction. (See the figure in Balancing Loop and the explanation below.)

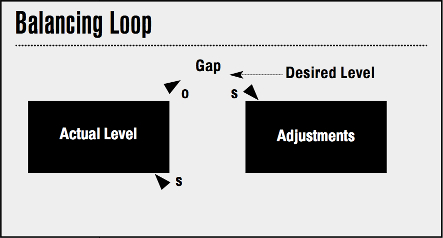

Balancing Loops

Balancing loops keep things in equilibrium. Much like the heating and air-conditioning system in your home that automatically regulates the temperature, a balancing system does exactly that—it balances.

Imagine that you have just purchased a new com- puter-based training software package. Your instructional design team will need at least a month to learn and work with the new software before they can feel proficient in using it. We could say, in effect, that there is a gap between their current level of knowledge with this software and their desired level of knowledge and skill. In order to close this gap, adjustments (that is, training) will need to be conducted.

Case Study: Systems Thinking Applications

In the early 1990s, Ford Motor Company decided it wanted to move into systems thinking. The Executive Development Center in Dearborn, Michigan, formed a group called the Systems Learning Network (SLN). This group was composed of various people from different parts of the company, each dedicated to learning systems thinking principles.

First, this group formulated a plan and then decided where to apply their new ideas. They began their thinking at the industry level and ultimately designed a computer simulation program that showed the interdependency of consumer demand and profitability.

Next, the group focused their efforts on five on-site projects where they could apply the principles of systems thinking: electronics, electrical, manufacturing, project development, and central staff. With multiple initiatives running concurrently, the group could discover more about synthesizing the variables to create a whole picture. To achieve this goal, the SLN asked questions such as: “What could we understand about the whole that is greater than the sum of the individual projects?” What do these applications tell us?” “How do we make progress from here?” Some of the key lessons acquired from the Systems Learning Network encompassed the following insights:

- Performance elements are interrelated.

- Start small and build complexity as you go. The real aim of systems thinking is to simplify complexity.

- It is important to energize and transform knowledge into programs, seminars, and projects in order to diffuse learning throughout Ford. Vic Leo summed up the systems thinking initiative at Ford as follows: “The systems approach means to think in terms of interdependencies; to energize; to put forth a picture that represents a more desirable future, one that has a chance of dissolving the...mess...not recreating the...mess somewhere else or fixing it temporarily. And that was what the excitement at this manufacturing plant was all about.”

Reading the Loop. If there is a gap between the desired level and the actual level, adjustments or interventions—in this case, training—are made to close the gap. Begin at the point where the gap is located. As you go around the loop and adjustments increase, the actual level of attainment will also increase. When this occurs, the gap decreases. Remember that an o link indicates a change in the opposite direction.

Additional considerations with loops are as follows:

- You can use both reinforcing and balancing loops to describe a problem. There is no rule stating that there can be only one type of loop.

- A balancing loop is fairly easy to recognize by adding the number of o’s contained in the loop; an odd total sum is your indicator for a balancing loop.

Loops as Archetypes

Earlier it was stated that you could combine both reinforcing loops and balancing loops to describe a situation or problem. To accomplish this, you essentially take the loops and place them in a structure called an “archetype.” An archetype is a generic configuration that can be applied to many different situations. It works much like a template.

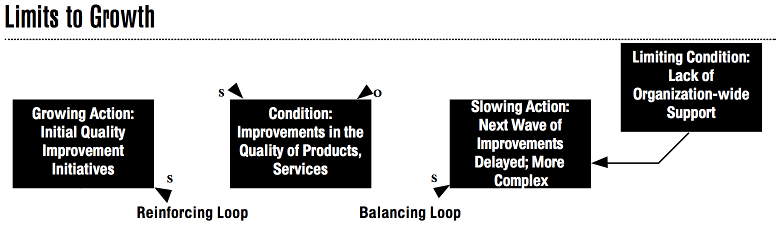

One of the most common archetypes, “limits to growth” was introduced by Peter Senge in his book The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. To define this archetype, most people have limits to growth structures. Essentially, this means that all individuals have a personal ceiling, and to go beyond that limit requires an outside intervention.

The simplest way to recognize the limits to growth structure is through behavior patterns. Is there a situation in which things get better at first, and then mysteriously stop improving? First you need to identify the reinforcing process—what is getting better, and what is the action or activity leading to improvement? It might, for instance, be the story of an organizational improvement: an equal opportunity hiring program. The growing action is the equal opportunity program itself, and the condition is the percentage of women and minorities on staff. As the percentage of women in management increases, confidence in or commitment to the program grows, leading to a larger number of women in management.

There is, however, bound to be a limiting factor. Typically it is an implicit goal or a limiting resource. The second step is to identify the limiting factor. What slowing action or resisting force starts to come into play to keep the condition from continually improving? Some managers may consciously or unconsciously decide to limit their continued support for any more quality initiatives throughout the organization. That unspoken number is the limiting condition; as soon as that threshold is approached, the slowing action—manager’s resistance—will kick in.

Now that we can delineate the problem through words, drawing an archetype that shows the interrelationships of the problem can help us visualize the situation. See the figure in Limits to Growth for an example of an archetype that uses both reinforcing and balancing loops.

Other common system archetypes have been identified in Daniel Kim’s book Systems Thinking Tools: A User’s Reference Guide. These include a “drifting goals” archetype, where there is a gap between the goal and the current reality. This gap can be resolved by taking corrective action or by lowering the goal. Corrective action takes more time, but will result in longer-term benefits; lowering the goal is more of a quick-fix solution.

Another archetype, called “shifting the burden,” solves a problem by applying a symptomatic solution that diverts attention away from a more fundamental solution. For example, management or human resources brings in an outside consultant, who solves the problem for the organization instead of acting as a catalyst who guides the organization to take responsibility for and solve its own problems.

Still another commonly used archetype is called “success to the successful,” which also can be thought of as a self-fulfilling prophecy. If a person or group is given more resources than another person or group, the former has a higher likelihood of success than the latter. The initial signs of success also justify devoting additional resources to the former.

Case Study: Health Care Field

According to John Couris, senior manager of quality management and education at Massachusetts General Hospital, the Radiology Department and the Orthopedic Department have in the past looked at the service they provide their patients independently. Each organization vertically focused its service improvement activities in an attempt to incrementally enhance the patient experience from a departmental perspective.

With the advent of new technology and a Web-image distribution system, both departments have begun to look at service provided to patients horizontally, using a systems thinking approach. They understand that looking at the care process as a system is essential to the long-term success of both departments as they strive to provide the best patient care. No longer can each afford to look at their processes as simply a functional/linear operation. It is too costly to do so in terms of duplication of effort and financial outlay. It also has a negative impact on operating efficiencies.

There have been challenges to implementation: total buy-in from leaders of the departments; navigation of the political landscape of both organizations; and allocation of resources. To address these challenges, the departments created an Orthopedic-Radiology Committee (now called the Computed Radiography Committee). In addition, they implemented a leadership training series that focuses on systems thinking.

These two groups now understand the importance of looking at the operations as one system. The benefits realized by leveraging technology and systems thinking include reducing patient throughput time by 34 percent and setting the stage for the proliferation of systems thinking as a leadership/management tool with the Radiology and Orthopedics Departments.

Effective Interventions

It is now time to take a step back and determine the most effective intervention. Let’s use the limits to growth example of the equal opportunity hiring program, cited above.

If you were to suggest a solution to this problem, one that would have the potential for long-term change, what would it be? Most people try to solve limits to growth problems by pushing harder (in this example, by adding more programs, trying to convince senior management that the program is working, or just continuing to give it another chance). In the beginning, these strategies may be effective. The harder you push, however, the more the balancing process will resist your efforts. According to Senge, the point of leverage is in the balancing loop, not the reinforcing loop. Your task is to identify and change the limiting factor.

So, in our example, the task will be to work with the managers’ resistance and to try to uncover the reasons behind their opposition. This usually requires a good deal of effort on your part; uncovering resistance involves engaging the manager in a dialogue that will uncover his or her deeply held thoughts, beliefs, and assumptions about management, control issues, and perceptions of power. Conducting these types of conversations actually encompasses one of the five disciplines of organizational learning, that of mental models.

Pulling It Together

We have come full circle in identifying the problem and the key place of intervention that promises the highest leverage in solving the problem. The Self-Managed Work Teams case study describes a scenario in which the skills of systems thinking can be applied. As an exercise, read the case study and then draw a behavior over time graph highlighting the key variables that have changed over time. Next, identify those variables that would tell a limits to growth story. Finally, decide where the key leverage point is—that point where you would make an intervention to help solve the problem.

Use the Systems Thinking Template, left, as you work on the story. Then check your own work against the Completed Business Story Template that follows this discussion. You may find it beneficial to work on this case study with another colleague as you learn to practice your new skills in systems thinking.

Relevance to HRD and Training

There is a basic premise that human performance can be improved only when training is viewed and managed as a process within a system that transcends typical organizational and administrative boundaries. In their book The Learning Alliance: Systems Thinking in Human Resource Development, Robert Brinkerhoff and Stephen Gill state that by understanding the principles of systems thinking and their impact on human resource development, we will begin to make this paradigm shift. According to Fritjof Capra and David Steindl-Rast’s text Belonging to the Universe: Explorations on the Frontiers of Science and Spirituality, this shift is from breaking things down into different compartments or functional areas to interdependence; from seeing individual programs to viewing a process; from quick-fix to analytic solutions; and from short-term results to long-term results. Capra and Steindl-Rast further state that the shift from parts thinking to whole thinking involves stepping back to see that the part is merely a pattern in an inseparable web of relationships.

One of the key steps in integrating systems thinking and training is to clearly and explicitly link training interventions and outcomes to business needs and strategic goals. This can be done by drawing a causal loop path between the training interventions and such outcomes as job behaviors and productivity. The path can show you where and in what ways the training results in measurable, high-leverage change.

Systems thinking encompasses looking at all the ramifications of your decisions and strategies. It asks you to question the types of behaviors you are rewarding. If you now reward the “fire-fighting” kind of reaction, what would happen in your organization if you started to reward people for making long-term, systemic changes? Systems thinking is not the latest management fad. It is a method of deep thinking that involves a shift in perspective to the whole of an organization and, in that process, enables people to pause and reflect on what is really important. This way, actions that are undertaken are more imaginative, creative, and effective. Everyone comes out a winner with this kind of thinking.

Case Study: Self-Managed Work Teams

A new senior manager had just been recruited into the Training and Education Department. This department had been experiencing satisfactory results for several years and had an average yearly turnover rate of 5.6 percent.

Two months after joining the department, this senior manager informed everyone that the department was now going to be a self-managed team. He was quite enthusiastic about this change, and his enthusiasm spread to the staff. Some staff members were a little skeptical about putting such a structure into effect, however, because the department was given carte blanche for proceeding with the implementation.

One particular employee took the initiative to organize training classes on what to expect from a self-managing team, what stages teams go through, what skills are needed, and so forth. This enabled the teams to get off to a good start. Staffers began communicating with one another and were ready to plan the implementation, organize the work flow, and determine how this change would affect their clients. Motivation was high; morale was heightened; productivity increased.

Word of the self-managed work team’s efforts and subsequent success got around the organization. At this point, the new senior manager stepped in and told the self-managed work team members to hold off and to refer all future initiatives to his attention before starting anything. After that, when any employee offered up ideas, those ideas, as well as any requests for support and training, were stonewalled by the manager: The ideas were great, he said, but could not be implemented now. These delay tactics continued throughout the design and implementation phase of the self-managed work team structure. Meanwhile, the senior manager began his own programs, bringing in outside people to implement the self-managed team structure.

As for the team, their initial, pumped-up levels of morale, motivation, and productivity remained high for a period of time, but then began to decline. Turnover rose dramatically—up to 17 percent. Senior management was disappointed and upset by this downturn, but rallied behind the idea of self-managed work teams. “Stick together as a team, and the process will succeed,” they told employees. The self-managed work team structure collapsed after 10 months.

Completed Business Story Template

After you have applied the principles of systems thinking to your business scenario or problem, check your work against this completed systems thinking template.

Step 1: Stating the Problem

A manager who has a tendency to thwart his staff’s efforts.

Step 2: Telling the Story

See the Self-Managed Work Teams case study.

Step 3: Identifying the Key Variables

- level of productivity, morale, and motivation

- turnover

- number of creative ideas from employees

- level of manager’s support

- manager’s basic need for control

- self-managed work teams

- number of roadblocks (people, programs)

Step 4: Visualizing the Problem

All of the above variables can be placed into a behavior over time graph to see how each one has changed over time (see Behavior Over Time figure).

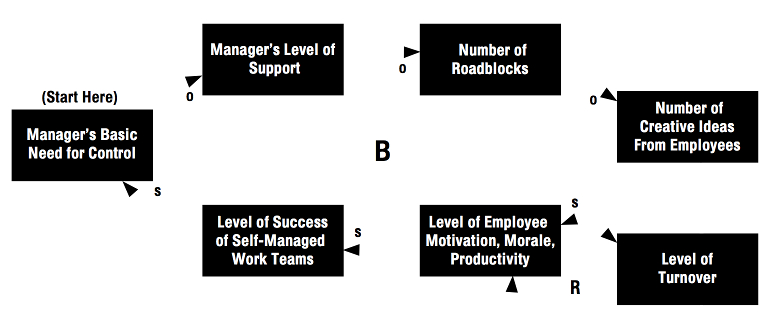

Step 5: Creating the Loops

- Begin with the manager’s basic need for control. Initially, this variable is rather low when the self-managed work teams are first introduced.

- As control is low, the manager’s level of support is increased. (Remember that o’s reflect a change in the opposite direction.)

- As support is heightened, the number of roadblocks is low. With no initial roadblocks, there is a growth in the number of creative ideas. Thus, the level of employee motivation, morale, and productivity also rises. (The s indicates a change in the same direction.)

- As motivation grows, the self-managed work team’s level of success increases. The more successful the self-managed work team becomes, the more the manager’s intrinsic need to control increases.

- With the need for more control, the manager’s support to the team decreases. As the manager’s support decreases, the number of roadblocks increases. This results in reduction of creative ideas from employees. Eventually, the self-managed work team collapses.

- The point of emphasis in this particular scenario is that as the success of the self-managed work team increases, the manager’s need for control increases (see Manager’s Need for Control figure).

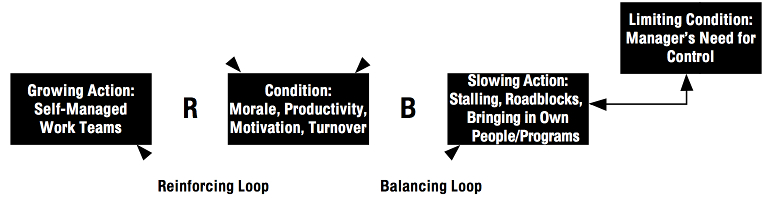

Step 6: Drawing Loops as an Archetype

- In a limits to growth archetype, the initial success of the self-managed work team creates better morale, increased productivity, self-sustaining motivation, and lower turnover.

- As these factors improve, slowing action tactics sneak into the picture, which then loop back to slow down the condition of morale, productivity, and so forth.

- The underlying reason is the limiting condition: the manager’s need for control (see Work Team Success figure).

Step 7: Determining the Intervention Point

The key leverage is to address the limiting condition: the manager’s need for control.

Step 8: Evaluating the Whole Process

- How did mapping the problem using systems thinking work?

- What worked well?

- How can this process apply to your own specific needs?

![]()

Manager’s Need for Control

Work Team Success