There is an old Hollywood saying which claims that ‘a good cutter cuts his own throat’, cutter meaning a film editor. What does this mean? Well, simply that the skills and craft employed by the film editor to stitch together a sequence of separate shots persuades the audience that they are watching a continuous event. They are unaware of the hundreds of subtle decisions that have been made during the course of the film. The action flows from shot to shot and appears natural and obvious. The editing skills and techniques that have achieved this are rendered invisible to the audience, and therefore the unenlightened may claim, ‘But what has the editor done? What is the editor’s contribution to the production?’ The editor has become anonymous and apparently his/her skills are redundant. As we have seen, nearly all TV craft skills employ invisible techniques.

A technical operator who is required to edit will usually be assigned to news or news feature items. This section examines the technique required for this type of programme format. Obviously the craft of editing covers a wide range of genres up to, and including the sophisticated creative decisions that are required to cut feature films. However, there is not such a wide gap between different editing techniques as first it would appear.

What is Editing?

Essentially editing is selecting and coordinating one shot with the next to construct a sequence of shots which form a coherent and logical narrative. There are a number of standard editing conventions and techniques that can be employed to achieve a flow of images that guide the viewer through a visual journey. A programme’s aim may be to provide a set of factual arguments that allows the viewer to decide on the competing points of view; it may be a dramatic entertainment utilizing editing technique to prompt the viewer to experience a series of highs and lows on the journey from conflict to resolution; or a news item’s intention may be to accurately report an event for the audience’s information or curiosity.

The manipulation of video, sound and picture, can only be achieved electronically, and an editor who aims to fully exploit the potential of television must master the basic technology of the medium. To the knowledge of technique and technology must be added the essential requirement of a supply of appropriate video and audio material. As we have seen in the section on camerawork, the cameraman, director or journalist needs to shoot with editing in mind. Unless the necessary shots are available for the item, an editor cannot cut a cohesive and structured story. A random collection of shots is not a story, and although an editor may be able to salvage a usable item from a series of ‘snapshots’, essentially editing is exactly like the well known computer equation which states that ‘garbage in’ equals ‘garbage out’.

![]() Burnt-in time code: In order for edit decisions to be made in a limited off-line preview facility, time code is superimposed on each picture of a copy of the original for easy identification of material.

Burnt-in time code: In order for edit decisions to be made in a limited off-line preview facility, time code is superimposed on each picture of a copy of the original for easy identification of material.

![]() Logging: Making a list of shots of the recorded material speeds up the selection and location (e.g. which cassette) of shots. When this is compiled on a computer it can be used as a reference to control which sections of the recorded images are to be digitalized.

Logging: Making a list of shots of the recorded material speeds up the selection and location (e.g. which cassette) of shots. When this is compiled on a computer it can be used as a reference to control which sections of the recorded images are to be digitalized.

![]() Edit decision list (EDL): The off-line edit decisions can be recorded on a floppy disk giving the tape source of the shot, its in and out time code or duration. In order to work across a range of equipment there are some widely adopted standards such as CMX, Sony, SMPTE, and Avid.

Edit decision list (EDL): The off-line edit decisions can be recorded on a floppy disk giving the tape source of the shot, its in and out time code or duration. In order to work across a range of equipment there are some widely adopted standards such as CMX, Sony, SMPTE, and Avid.

![]() Conform: The set of instructions contained in the EDL can be used to directly control conforming in an on-line edit suite dubbing from source tape to master tape adding any effects or special transitions between shots as required.

Conform: The set of instructions contained in the EDL can be used to directly control conforming in an on-line edit suite dubbing from source tape to master tape adding any effects or special transitions between shots as required.

![]() Auto assemble: Editing process using an edit controller programmed with the required edit point identified by time code, which automatically runs the source tape back for the requisite run-up time and then runs both source and master VTRs to make a perfect edit transition.

Auto assemble: Editing process using an edit controller programmed with the required edit point identified by time code, which automatically runs the source tape back for the requisite run-up time and then runs both source and master VTRs to make a perfect edit transition.

![]() Uncommitted editing: This technique can only be achieved in a true random access edit suite where the source material has been digitalized and stored on high density memory chips (integrated circuits). Hard disk video storage systems require more than one TV interval (1.6 ms or less) to reposition their read/write heads (typically 10 ms) to access any part of the disk, so replay is limited to accessing the next track, rather than any track and therefore any picture. Uncommitted editing allows any shot to be played out in any order in real time under the control of the EDL. Because the playout is not re-recorded in a fixed form, it is uncommitted and trimming any cut or re-cutting the material for a different purpose is relatively simple.

Uncommitted editing: This technique can only be achieved in a true random access edit suite where the source material has been digitalized and stored on high density memory chips (integrated circuits). Hard disk video storage systems require more than one TV interval (1.6 ms or less) to reposition their read/write heads (typically 10 ms) to access any part of the disk, so replay is limited to accessing the next track, rather than any track and therefore any picture. Uncommitted editing allows any shot to be played out in any order in real time under the control of the EDL. Because the playout is not re-recorded in a fixed form, it is uncommitted and trimming any cut or re-cutting the material for a different purpose is relatively simple.

![]() Timebase corrector (TBC): Most VTRs have a TBC to correct the timing inaccuracies of the pictures coming from tape.

Timebase corrector (TBC): Most VTRs have a TBC to correct the timing inaccuracies of the pictures coming from tape.

![]() Tracking: Tracking is adjusting the video heads of the VTR over the picture information recorded on tape to give the strongest signal. The position of the heads should also be in a constant relationship with the control track.

Tracking: Tracking is adjusting the video heads of the VTR over the picture information recorded on tape to give the strongest signal. The position of the heads should also be in a constant relationship with the control track.

![]() Pre-roll: The pre-roll is the time needed by a VTR to reach the operating speed to produce a stable picture. With some VTRs this can be as little as a single frame. When two or more transports are running up together, it is highly unlikely that they will all play, lock and colour frame within a few frames as they each chase and jockey to lock up correctly. For this reason, virtually all transport based editing systems provide for an adjustable pre-roll duration. This cues the machine to a predefined distance from the required in-point in order that, with a suitable cue, all synchronized devices can reliably lock in time for the required event. VTRs also have to achieve a predetermined time code off-set to each other – so lengthening the overall lock-up time.

Pre-roll: The pre-roll is the time needed by a VTR to reach the operating speed to produce a stable picture. With some VTRs this can be as little as a single frame. When two or more transports are running up together, it is highly unlikely that they will all play, lock and colour frame within a few frames as they each chase and jockey to lock up correctly. For this reason, virtually all transport based editing systems provide for an adjustable pre-roll duration. This cues the machine to a predefined distance from the required in-point in order that, with a suitable cue, all synchronized devices can reliably lock in time for the required event. VTRs also have to achieve a predetermined time code off-set to each other – so lengthening the overall lock-up time.

![]() Preview: Previewing an edit involves rehearsing the point of a transition between two shots without switching the master VTR to record to check that it is editorially and technically acceptable.

Preview: Previewing an edit involves rehearsing the point of a transition between two shots without switching the master VTR to record to check that it is editorially and technically acceptable.

![]() Split edit: An edit where the audio and video tracks are edited at different points.

Split edit: An edit where the audio and video tracks are edited at different points.

The Technology of News Editing

Video and audio can be recorded on a number of mediums such as tape, optical, hard disk, or high density memory chips (integrated circuits). Tape has been the preferred method of acquisition because of its storage capacity and cost. An edit suite will be defined by the format of its principal VTR machines, but will often be equipped with other VTR machine formats to allow transfer of acquisition material to the main editing format, or to provide lower quality copies for off-line editing or previewing.

The other defining technology of the edit suite is if the edited tape has been recorded in analogue or digital format, (see Television engineering, pages 34–47), and the format of the finished master tape.

Video Editing

Recorded video material from the camera almost always requires rearrangement and selection before it can be transmitted. Selective copying from this material onto a new recording is the basis of the video editing craft. Selecting the required shots, finding ways to unobtrusively cut them together to make up a coherent, logical, narrative progression takes time. Using a linear editing technique (i.e. tape-to-tape transfer), and repeatedly re-recording the material exposes the signal to possible distortions and generation losses. Some digital VTR formats very much reduce these distortions. An alternative to this system is to store all the recorded shots on disc or integrated circuits to make up an edit list detailing shot order and source origin (e.g. cassette number, etc.) which can then be used to instruct VTR machines to automatically dub across the required material, or to instruct storage devices to play out shots in the prescribed edit list order.

On tape, an edit is performed by dubbing across the new shot from the originating tape onto the out point of the last shot on the master tape. Simple non-linear disk systems may need to shuffle their recorded data in order to achieve the required frame-to-frame sequence whereas there is no re-recording required in random access editing, simply an instruction to read frames in a new order from the storage device.

Off-Line Editing

Off-line editing allows editing decisions to be made using low-cost equipment to produce an edit decision list (EDL, see Glossary), or a rough cut which can then be conformed or referred to in a high quality on-line suite. A high-quality/high-cost edit suite is not required for such decision making, although very few off-line edit facilities allow settings for DVEs, colour correctors or keyers. Low-cost off-line editing allows a range of story structure and edit alternatives to be tried out before tying up a high-cost on-line edit suite to produce the final master tape.

![]() Digital video effect (DVE): This is the manipulation of a digitalized video signal such as squeezing, picture bending, rotations and flipping, etc. These effects can be used as an alternative to a cut or a dissolve transition between two images (see Section 9: Vision mixing).

Digital video effect (DVE): This is the manipulation of a digitalized video signal such as squeezing, picture bending, rotations and flipping, etc. These effects can be used as an alternative to a cut or a dissolve transition between two images (see Section 9: Vision mixing).

![]() Video graphics: Electronically created visual material is usually provided for an editing session from a graphics facility, although character generators for simple name-supers are sometimes installed in edit suites.

Video graphics: Electronically created visual material is usually provided for an editing session from a graphics facility, although character generators for simple name-supers are sometimes installed in edit suites.

![]() Frame store: Solid state storage of individual frames of video. Frames can be grabbed from any video source, filed and later recovered for production purposes.

Frame store: Solid state storage of individual frames of video. Frames can be grabbed from any video source, filed and later recovered for production purposes.

![]() Jam/slave time code: Sometimes time code needs to be copied or regenerated on a re-recording. Slave and jam sync generators provide for the replication of time code signals.

Jam/slave time code: Sometimes time code needs to be copied or regenerated on a re-recording. Slave and jam sync generators provide for the replication of time code signals.

![]() Crash record/crash edit: This is the crudest form of editing by simply recording over an existing recording without reference to time code, visual or audio continuity.

Crash record/crash edit: This is the crudest form of editing by simply recording over an existing recording without reference to time code, visual or audio continuity.

![]() Colour framing: It is necessary when editing in composite video, to maintain the correct field colour phase sequencing. In PAL, it is possible to edit different shots on every second frame (4 fields) without the relocking being visible. Analogue and digital component formats have no subcarrier and so the problem does not exist.

Colour framing: It is necessary when editing in composite video, to maintain the correct field colour phase sequencing. In PAL, it is possible to edit different shots on every second frame (4 fields) without the relocking being visible. Analogue and digital component formats have no subcarrier and so the problem does not exist.

![]() Match frame (edit): An invisible join within a shot. This is only possible if there is no movement or difference between the frames – the frames have to match in every particular.

Match frame (edit): An invisible join within a shot. This is only possible if there is no movement or difference between the frames – the frames have to match in every particular.

![]() A and B rolls: Two cassettes of original footage either with different source material are used to eliminate constant cassette change (e.g. interviews on one tape A, cutaways on tape B) or the original and a copy of the original to allow dissolves, wipes or DVEs between material originally recorded on the same cassette.

A and B rolls: Two cassettes of original footage either with different source material are used to eliminate constant cassette change (e.g. interviews on one tape A, cutaways on tape B) or the original and a copy of the original to allow dissolves, wipes or DVEs between material originally recorded on the same cassette.

![]() Cutting copy: An edited, low quality version used as a guide and reference in cutting the final, full quality editing master.

Cutting copy: An edited, low quality version used as a guide and reference in cutting the final, full quality editing master.

![]() Trim (edit): A film editing term for cutting a few frames of an in or out point. It is possible to trim the current edit point in linear editing, but becomes difficult to attempt this on a previous edit. This is not a problem with random access editing.

Trim (edit): A film editing term for cutting a few frames of an in or out point. It is possible to trim the current edit point in linear editing, but becomes difficult to attempt this on a previous edit. This is not a problem with random access editing.

Editing Compressed Video

Care must be taken when editing compressed video to make certain that the edit point of an incoming shot is a complete frame, and does not rely (during compression decoding), on information from a preceding frame.

Archive Material

When editing news and factual programmes, there is often a requirement to use library material that may have been recorded in an older, and possibly obsolete video format (e.g. 2 inch Quadruplex, U-matic, etc.). Most news material before the 1980s was shot on film, and facilities may be required to transfer film or video material to the current editing format when needed.

An edit suite is where the final edit is performed in full programme quality. Each shot transition and audio will be selected and dubbed onto the master tape. The alternative to the high cost of making all edit decisions using broadcast equipment, is to log and preview all the material, and choose edit points on lower quality replay/edit facilities. These edit decision lists can then be used to carry out an auto-transfer dub in the on-line edit suite. Preparation in an off-line suite will help save time and money in the on-line facility.

Linear Editing

Cameras recording on tape are recording in a linear manner. When the tape is edited, it has to be spooled backwards and forwards to access the required shot. This is time consuming with up to 40% of the editing session spent spooling, jogging and previewing edits. Although modern VTRs have a very quick lock-up, usually less than a second, which allows relatively short pre-rolls, normally all edits are previewed. This involves performing everything connected with the edit except allowing the record machine to record. The finished edited master has limited flexibility for later readjustment, and requires a return to an edit session with the originating tapes if a different order of shots is required. Nevertheless, this method of editing video has been in use since the 1950s, and has only been challenged as the standard technique in the late 1980s when technology became available to transfer, store and edit video material in a non-linear way. Tape-to-tape editing then became known as linear editing. There are two types of linear editing:

![]() Insert editing records new video and audio over existing recorded material (often black and colour burst) on a ‘striped’ tape. Striped tape is prepared (often referred to as blacking up a tape) before the editing session by recording a continuous control track and time code along its complete length. This is similar to the need to format a disk before its use in a computer. This pre-recording also ensures that the tape tension is reasonably stable across the length of the tape. During the editing session, only new video and audio is inserted onto the striped tape leaving the existing control track and time code already recorded on the tape, undisturbed. This minimizes the chance of any discontinuity in the edited result. It ensures that it is possible to come ‘out’ of an edit cleanly, and return to the recorded material without any visual disturbance. This is the most common method of video tape editing and is the preferred alternative to assemble editing.

Insert editing records new video and audio over existing recorded material (often black and colour burst) on a ‘striped’ tape. Striped tape is prepared (often referred to as blacking up a tape) before the editing session by recording a continuous control track and time code along its complete length. This is similar to the need to format a disk before its use in a computer. This pre-recording also ensures that the tape tension is reasonably stable across the length of the tape. During the editing session, only new video and audio is inserted onto the striped tape leaving the existing control track and time code already recorded on the tape, undisturbed. This minimizes the chance of any discontinuity in the edited result. It ensures that it is possible to come ‘out’ of an edit cleanly, and return to the recorded material without any visual disturbance. This is the most common method of video tape editing and is the preferred alternative to assemble editing.

![]() Assemble editing is a method of editing onto blank (unstriped) tape in a linear fashion. The control track, time code, video and audio are all recorded simultaneously and joined to the end of the previously recorded material. This can lead to discontinuities in the recorded time code and especially with the control track if the master tape is recorded on more than one VTR.

Assemble editing is a method of editing onto blank (unstriped) tape in a linear fashion. The control track, time code, video and audio are all recorded simultaneously and joined to the end of the previously recorded material. This can lead to discontinuities in the recorded time code and especially with the control track if the master tape is recorded on more than one VTR.

Line-Up

A start-of-day check in an edit suite would include:

![]() Switch on all equipment.

Switch on all equipment.

![]() Select machine source on edit controller.

Select machine source on edit controller.

![]() Check routeing of video and audio.

Check routeing of video and audio.

![]() Line-up video monitors with PLUGE or bars.

Line-up video monitors with PLUGE or bars.

![]() Check bars and tone from replay to record machine.

Check bars and tone from replay to record machine.

![]() Check playback of video/audio from playback and record machine.

Check playback of video/audio from playback and record machine.

![]() If available, check the operation of the video and audio mixing panels.

If available, check the operation of the video and audio mixing panels.

![]() Black-up tape: record on a complete tape, a colour TV signal (without picture information), plus sync pulses, colour burst, and black level for use for insert editing.

Black-up tape: record on a complete tape, a colour TV signal (without picture information), plus sync pulses, colour burst, and black level for use for insert editing.

The master tape is the result of the editing session. It can also exist as an edit playout list for shots stored on disc.

Video editing can only be achieved with precision if there is a method of uniquely identifying each frame. Usually at the point of origination in the camera (see Working on location, pages 96–117), a time code number identifying hour, minute, second, and frame is recorded on the tape against every frame of video. This number can be used when the material is edited, or a new series of numbers can be generated and added before editing. A common standard is the SMPTE/EBU which is an 80 bit code defined to contain sufficient information for most video editing tasks.

![]() Code word: every frame contains an 80 bit code word which contains ‘time bits’ (8 decimal numbers), recording hours, minutes, seconds, frames and other digital synchronizing information. All this is updated every frame but there is room for additional ‘user bit’ information.

Code word: every frame contains an 80 bit code word which contains ‘time bits’ (8 decimal numbers), recording hours, minutes, seconds, frames and other digital synchronizing information. All this is updated every frame but there is room for additional ‘user bit’ information.

![]() User bit: user-bit allows up to nine numbers and an A to F code to be programmed into the code word which is recorded every frame. Unlike the ‘time bits’, the user bits remain unchanged until reprogrammed. They can be used to identify production, cameraman, etc.

User bit: user-bit allows up to nine numbers and an A to F code to be programmed into the code word which is recorded every frame. Unlike the ‘time bits’, the user bits remain unchanged until reprogrammed. They can be used to identify production, cameraman, etc.

There are two types of time code – record run and free run.

![]() Record run: record run only records a frame identification when the camera is recording. The time code is set to zero at the start of the day’s operation, and a continuous record is produced on each tape covering all takes. It is customary practice to record the tape number in place of the hour section on the time code. For example, the first cassette of the day would start 01.00.00.00, and the second cassette would start 02.00.00.00. Record run is the preferred method of recording time code on most productions.

Record run: record run only records a frame identification when the camera is recording. The time code is set to zero at the start of the day’s operation, and a continuous record is produced on each tape covering all takes. It is customary practice to record the tape number in place of the hour section on the time code. For example, the first cassette of the day would start 01.00.00.00, and the second cassette would start 02.00.00.00. Record run is the preferred method of recording time code on most productions.

![]() Free run: in free run, the time code is set to the actual time of day, and when synchronized, is set to run continuously. Whether the camera is recording or not, the internal clock will continue to operate. When the camera is recording, the actual time of day will be recorded on each frame. This mode of operation is useful in editing when covering day-long events such as conferences or sport. Any significant action can be logged by time as it occurs and can subsequently be quickly found by reference to the time-of-day code on the recording. In free run, a change in shot will produce a gap in time code proportional to the amount of time that elapsed between actual recordings. These missing time code numbers can cause problems with the edit controller when it rolls back from an intended edit point, and is unable to find the time code number it expects there (i.e. the time code of the frame to cut on, minus the pre-roll time).

Free run: in free run, the time code is set to the actual time of day, and when synchronized, is set to run continuously. Whether the camera is recording or not, the internal clock will continue to operate. When the camera is recording, the actual time of day will be recorded on each frame. This mode of operation is useful in editing when covering day-long events such as conferences or sport. Any significant action can be logged by time as it occurs and can subsequently be quickly found by reference to the time-of-day code on the recording. In free run, a change in shot will produce a gap in time code proportional to the amount of time that elapsed between actual recordings. These missing time code numbers can cause problems with the edit controller when it rolls back from an intended edit point, and is unable to find the time code number it expects there (i.e. the time code of the frame to cut on, minus the pre-roll time).

Time Code Track on Beta Tape?

Film began with recording images of actuality events such as a train arriving at a station, or workers leaving a factory. These were viewed by the audience as a single shot lasting as long as the amount of film that was wound through the camera. Within a few years, the audiences developed a taste for a story, a continuity element connecting the separate shots, and so narrative film techniques began to be developed. The visual storytelling methods chosen ensured the audience understood the action. Shooting and editing had to develop ways of presenting the causal, spatial and temporal relationship between shots. This was a completely new craft, and other story-telling disciplines such as theatre or literature were of little help in providing solutions to the basic visual problems faced by these early pioneers.

Film makers soon learnt how to make a cut on action in order to provide a smoother transition between two shots, and invented a number of other continuity editing techniques. The classical grammar of film editing was invented and understood not only by the film makers, but also by the film audience. It is the basis of most types of programme making to this day.

Continuity Editing

Continuity editing ensures that:

![]() shots are structured to allow the audience to understand the space, time and logic of the action

shots are structured to allow the audience to understand the space, time and logic of the action

![]() each shot follows the line of action to maintain consistent screen direction so that the geography of the action is completely intelligible

each shot follows the line of action to maintain consistent screen direction so that the geography of the action is completely intelligible

![]() unobtrusive camera movement and shot change directs the audience to the content of the production rather than the mechanics of production

unobtrusive camera movement and shot change directs the audience to the content of the production rather than the mechanics of production

![]() continuity editing creates the illusion that distinct, separate shots (possibly recorded out of sequence and at different times), form part of a continuous event being witnessed by the audience.

continuity editing creates the illusion that distinct, separate shots (possibly recorded out of sequence and at different times), form part of a continuous event being witnessed by the audience.

The Birth of ‘Invisible Technique’

As the early film pioneers discovered, it is not possible, without distracting the audience, to simply cut one shot to another unless certain basic continuity rules are followed. The aim is to ensure the spectator understands the story or argument by being shown a variety of shots, without being aware that in fact the shots are changing. Visual storytelling has two objectives – to communicate the required message, and to sustain the interest of the audience. Changing shot would appear to interrupt the viewer’s flow of attention, and yet it is an essential part of editing technique in structuring a sequence of shots, and to control the audience’s understanding of the intended message. There are a number of ways to make the transition from one shot to the next (see Visual transitions, page 174 for a full description).

![]() Check script or brief for tape numbers.

Check script or brief for tape numbers.

![]() Select and check tape cassette for correct material.

Select and check tape cassette for correct material.

![]() If time allows preview all material with reference to any shot list or running order that has been prepared.

If time allows preview all material with reference to any shot list or running order that has been prepared.

![]() Check the anticipated running time of the piece.

Check the anticipated running time of the piece.

![]() Transfer bars and tone and then the ident clock onto the front of the final edit cassette (master tape).

Transfer bars and tone and then the ident clock onto the front of the final edit cassette (master tape).

The Technical Requirements for an Edit

![]() Enter the replay time code in and out points into the edit controller.

Enter the replay time code in and out points into the edit controller.

![]() Enter the record tape time code in-point.

Enter the record tape time code in-point.

![]() Preview the edit.

Preview the edit.

![]() Check sync stability for the pre-roll time when using time-of-day time code.

Check sync stability for the pre-roll time when using time-of-day time code.

![]() Make the edit.

Make the edit.

![]() Check the edit is technically correct in sound and vision and the edit occurs at the required place.

Check the edit is technically correct in sound and vision and the edit occurs at the required place.

![]() When two shots are cut together, check that there is continuity across the cut and the transition (to an innocent eye) is invisible.

When two shots are cut together, check that there is continuity across the cut and the transition (to an innocent eye) is invisible.

The Importance of Audio

Audio plays a crucial part in editing and requires as much attention as video. See Section 5: Audio technical operations.

Perception and Shot Transition

Film and television screens display a series of single images for a very short period of time. Due to the nature of human perception (persistence of vision), if these images are displayed at more than 24 times a second, the viewer no longer sees a series of individual snapshots, but the illusion of continuous motion of any subject that changes position in succeeding frames.

It takes time for a change of shot to be registered, and with large discrepancies between shot transitions, it becomes more apparent to the viewer when the composition of both shots is dissimilar. If the programme maker aims to make the transition between shots to be as imperceptible as possible in order to avoid visually distracting the viewer, the amount of eye movement between cuts needs to be at a minimum. If the incoming shot is sufficiently similar in design (e.g. matching the principal subject position and size in both shots), the movement of the eye will be minimized and the change of shot will hardly be noticeable. There is, however, a critical point in matching identical shots to achieve an unobtrusive cut (e.g. cutting together the same size shot of the same individual), where the jump between almost identical shots becomes noticeable.

Narrative motivation for changing the shot (e.g. ‘What happens next? What is this person doing?’ etc.) will also smooth the transition. A large mismatch between two shots, for example, action on the left of frame is cut to when the previous shot has significant action on extreme right of frame, may take the viewer four or five frames to catch up with the change, and trigger a ‘What happened then?’ response. If a number of these ‘jump’ cuts (i.e. shot transitions that are noticeable to the audience), are strung together, the viewer becomes very aware of the mechanics of the production process, and the smooth flow of images is disrupted. This ‘visual’ disruption, of course, may sometimes be a production objective.

Matching Visual Design Between Shots

When two shots are cut together, the visual design, that is the composition of each shot, can be matched to achieve smooth continuity. Alternatively, if the production requirement is for the cut to impact on the viewer, the juxtaposition of the two shots can be so arranged to provide an abrupt contrast in their graphic design. The cut between two shots can be made invisible if the incoming shot has one or more similar compositional elements as the preceding shot. The relationships between the two shots may relate to similar shape, similar position of dominant subject in the frame, colours, lighting, setting, overall composition, etc. Any similar aspects of visual design that is present in both shots will help the smooth transition from one shot to the next.

Matching Spatial Relationships Between Shots

Editing creates spatial relationships between subjects which need never exist in reality. A common example is a passenger getting into a train at a station. The following shot shows a train pulling out of the station. The audience infers that the passenger is in the train when they are more probably on an entirely different train or even no train at all. Any two subjects or events can be linked by a cut if there is an apparent graphic continuity between shots framing them, and if there is an absence of an establishing shot showing their physical relationship. Portions of space can be cut together to create a convincing screen space provided no shot is wide enough to show that the edited relationship is not possible.

Matching Tone, Colour or Background

Cutting between shots of speakers with different background tones, colour or texture will sometimes result in an obtrusive cut. A cut between a speaker with a bright background and a speaker with a dark background will result in a ‘jump’ in the flow of images each time it occurs. Colour temperature matching and background brightness relies on the cameraman making the right exposure and artiste positioning decisions. Particular problems can occur, for example, with the colour of grass which changes between shots. Face tones of a presenter or interviewee need to be consistent across a range of shots when cut together in a sequence. Also, cutting between shots with in-focus and defocused backgrounds to speakers can produce a mismatch on a cut. Continuity of colour, tone, texture, skin tones, and depth of field, will improve the seamless flow of images.

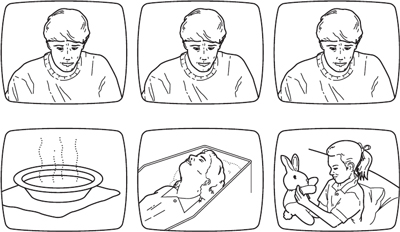

Kuleshov and I made an interesting experiment. We took from some film or other several close-ups of the well known Russian actor Mosjukhin. We chose closeups which were static and which did not express any feeling at all – quiet close-ups. We joined these close-ups, which were all similar, with other bits of film in three different combinations.

In the first combination the close-up of Mosjukhin was looking at the soup. In the second combination the face of Mosjukhin was joined in shots showing a coffin in which lay a dead woman. In the third the close-up was followed by a shot of a little girl playing with a funny toy bear. When we showed the three combinations to an audience which had not been let into the secret the result was terrific. The public raved about the acting of the artist. They pointed out the heavy pensiveness of his mood over the forgotten soup, were touched and moved by the deep sorrow which looked on the dead woman, and admired the light, happy smile with which he surveyed the girl at play. But we knew that in all three cases the face was exactly the same.

Film Technique and Film Acting

V.I. Pudovkin

Matching Rhythm Relationships Between Shots

The editor needs to consider two types of rhythm when cutting together shots; the rhythm created by the rate of shot change, and the internal rhythm of the depicted action.

Each shot will have a measurable time on screen. The rate at which shots are cut creates a rhythm which affects the viewer’s response to the sequence. For example, in a feature film action sequence, a common way of increasing the excitement and pace of the action is to increase the cutting rate by decreasing the duration of each shot on screen as the action approaches a climax. The rhythms introduced by editing are in addition to the other rhythms created by artiste movement, camera movement, and the rhythm of sound. The editor can therefore adjust shot duration and shot rate independent of the need to match continuity of action between shots; this controls an acceleration or deceleration in the pace of the item.

By controlling the editing rhythm, the editor controls the amount of time the viewer has to grasp and understand the selected shots. Many productions exploit this fact in order to create an atmosphere of mystery and confusion by ambiguous framing and rapid cutting which deliberately undermines the viewer’s attempt to make sense of the images they are shown.

Another editing consideration is maintaining the rhythm of action carried over into succeeding shots. Most people have a strong sense of rhythm as expressed in walking, marching, dancing, etc. If this rhythm is destroyed, as for example, cutting together a number of shots of a marching band so that their step becomes irregular, viewers will sense the discrepancies, and the sequence will appear disjointed and awkward. When cutting from a shot of a person walking, for example, care must be taken that the person’s foot hits the ground with the same rhythm as in the preceding shot, and that it is the appropriate foot (e.g. after a left foot comes a right foot). The rhythm of a person’s walk may still be detected even if the incoming shot does not include the feet. The beat of the movement must not be disrupted. Sustaining rhythms of action may well override the need for a narrative ‘ideal’ cut at an earlier or later point.

Matching Temporal Relationships Between Shot

The position of a shot in relation to other shots (preceding or following) will control the viewer’s understanding of its time relationship to surrounding shots. Usually a factual event is cut in a linear time line unless indicators are built in to signal flash-backs or very rarely, flash-forwards. The viewer assumes the order of depicted events is linked to the passing of time. The duration of an event can be considerably shortened to a fraction of its actual running time by editing if the viewer’s concept of time passing is not violated. The standard formula for compressing space and time is to allow the main subject to leave frame, or to provide appropriate cutaways to shorten the actual time taken to complete the activity. While they are out of shot, the viewer will accept that greater distance has been travelled than is realistically possible.

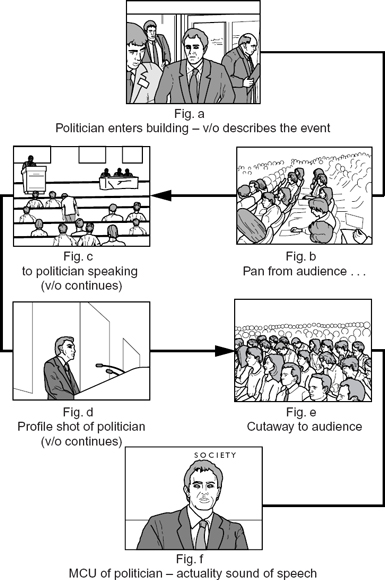

For example, a politician enters a conference hall and delivers a speech to an audience. This whole event, possibly lasting 30 minutes or more, can be reduced to 15 seconds of screen time by cutting between the appropriate shots. In the first shot (Fig. a), the politician is seen entering the building with a voice-over giving details of the purpose of the visit. A cutaway to an audience shot with a pan to the politician on the platform (Figs b and c), allows all the intervening time to be collapsed without a jump cut, and also allows the voice-over to paraphrase what the politician is saying. A third, closer, profile shot of the politician (Fig. d), followed by a shot of the listening audience (Fig. e), continues with the voice-over paraphrase, ending with a MCU of the politician (Fig. f), with his actuality sound, delivering the key ‘sound bite’ sentence of his speech. A combination of voice-over and five shots that can be cut together maintaining continuity of time and place allows a 30 minute event to be delivered in 15/20 seconds.

Provided the main subject does not leap in vision from location one immediately to location two, and then to three and four, there will be no jump in continuity between shots. The empty frames and cutaways allow the editing-out of space and time to remain invisible. News editing frequently requires a reduction in screen time of the actual duration of a real event. For example, a 90 minute football match recording will be edited down to 30 seconds to run as a ‘highlights’ report in a news bulletin. Screen time is seldom made greater than the event time, but there are instances, for example, in reconstructions of a crime in a documentary, where time is expanded by editing. This stylistic mannerism is often accompanied by slow motion sequences.

Rearranging Time and Space

When two shots are cut together, the audience attempts to make a connection between them. For example, a man on a station platform boards a train. A wide shot shows a train pulling out of a station. The audience makes the connection that the man is in the train. A cut to a close shot of the seated man follows, and it is assumed that he is travelling on the train. We see a wide shot of a train crossing the Forth Bridge, and the audience assumes that the man is travelling in Scotland. Adding a few more shots would allow a shot of the man leaving the train at his destination with the audience experiencing no violent discontinuity in the depiction of time or space. And yet a journey that may take two hours is collapsed to thirty seconds of screen time, and a variety of shots of trains and a man at different locations have been strung together in a manner that convinces the audience they have followed the same train and man throughout a journey.

Basic Editing Principles

This way of arranging shots is fundamental to editing. Space and time are rearranged in the most efficient way to present the information that the viewer requires to follow the argument presented. The transition between shots must not violate the audience’s sense of continuity between the actions presented. This can be achieved by:

![]() Continuity of action: action is carried over from one shot to another without an apparent break in speed or direction of movement (see figure opposite).

Continuity of action: action is carried over from one shot to another without an apparent break in speed or direction of movement (see figure opposite).

![]() Screen direction: if the book is travelling left to right in the medium shot, the closer shot of the book will need to roughly follow the same direction (see figure opposite). A shot of the book moving right to left will produce a visual ‘jump’ which may be apparent to the viewer.

Screen direction: if the book is travelling left to right in the medium shot, the closer shot of the book will need to roughly follow the same direction (see figure opposite). A shot of the book moving right to left will produce a visual ‘jump’ which may be apparent to the viewer.

![]() Eyeline match: the eyeline of someone looking down at the book should be in the direction the audience believes the book to be. If they look out of frame with their eyeline levelled at their own height, the implication is that they are looking at something at that height. Whereas if they were looking down, the assumption would be that they are looking at the book.

Eyeline match: the eyeline of someone looking down at the book should be in the direction the audience believes the book to be. If they look out of frame with their eyeline levelled at their own height, the implication is that they are looking at something at that height. Whereas if they were looking down, the assumption would be that they are looking at the book.

There is a need to cement the spatial relationship between shots. A subject speaking and looking out of the left of frame will be assumed by the viewer to be speaking to someone off camera to the left. A cut to another person looking out of frame to the right will confirm this audience expectation. Eyeline matches are decided by position, (see crossing the line on page 69), and there is very little that can be done at the editing stage to correct shooting mismatches except flipping the frame to reverse the eyeline which alters the continuity of the symmetry of the face and other left/right continuity elements in the composition such as hair partings, etc.

In a medium shot, for example (Fig. a), someone places a book on a table out of shot. A cut to a closer shot of the book (Fig. b), shows the book just before it is laid on the table. Provided the book’s position relative to the table and the speed of the book’s movement in both shots is similar, and there is continuity in the table surface, lighting, hand position, etc., then the cut will not be obtrusive. A close shot that crosses the line (Fig. c) will not cut.

Shot Size

Another essential editing factor is the size of shots that form an intercut sequence of faces. A cut from a medium close up to another medium close up of another person will be unobtrusive provided the eyeline match is as above. A number of cuts between a long shot of one person and a medium close up of another will jump and be obtrusive.

There are a number of standard editing techniques that are used across a wide range of programme making. These include:

![]() Intercutting editing can be applied to locations or people. The technique of intercutting between different actions that are happening simultaneously at different locations was discovered as early as 1906 to inject pace and tension into a story. Intercutting on faces in the same location presents the viewer with changing viewpoints on action and reaction.

Intercutting editing can be applied to locations or people. The technique of intercutting between different actions that are happening simultaneously at different locations was discovered as early as 1906 to inject pace and tension into a story. Intercutting on faces in the same location presents the viewer with changing viewpoints on action and reaction.

![]() Analytical editing breaks a space down into separate framings. The classic sequence begins with a long shot to show relationships and the ‘geography’ of the setting followed by closer shots to show detail, and to focus on important action.

Analytical editing breaks a space down into separate framings. The classic sequence begins with a long shot to show relationships and the ‘geography’ of the setting followed by closer shots to show detail, and to focus on important action.

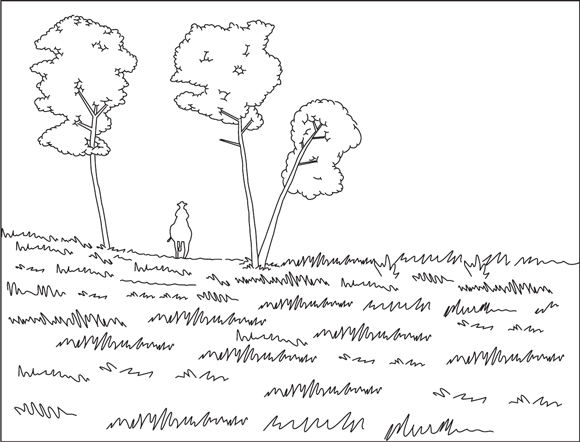

![]() Contiguity editing follows action through different frames of changing locations. The classic pattern of shots in a western chase sequence is where one group of horsemen ride through the frame past a distinctive tree to be followed later, in the same framing, by the pursuers riding through shot past the same distinctive tree. The tree acts as a ‘signpost’ for the audience to establish location, and as a marker of the duration of elapsed time between the pursued and the pursuer.

Contiguity editing follows action through different frames of changing locations. The classic pattern of shots in a western chase sequence is where one group of horsemen ride through the frame past a distinctive tree to be followed later, in the same framing, by the pursuers riding through shot past the same distinctive tree. The tree acts as a ‘signpost’ for the audience to establish location, and as a marker of the duration of elapsed time between the pursued and the pursuer.

![]() The point-of-view shot. A variant of this, which establishes the relationship between different spaces, is the point-of-view shot. Someone on-screen looks out of one side of the frame. The following shot reveals what the person is looking at. This can also be applied to anyone moving and looking out of frame, followed by their moving point-of-view shot.

The point-of-view shot. A variant of this, which establishes the relationship between different spaces, is the point-of-view shot. Someone on-screen looks out of one side of the frame. The following shot reveals what the person is looking at. This can also be applied to anyone moving and looking out of frame, followed by their moving point-of-view shot.

Summary of Perennial Technique

These editing techniques form the basics of an invisible craft which has been developed over nearly a hundred years of film and video productions. There are innovation and variation on these basic tenets, but the majority of television programme productions use these standard editing conventions to keep the viewers’ attention on the content of the programme rather than its method of production. These standard conventions are a response to the need to provide a variety of ways of presenting visual information coupled with the need for them to be unobtrusive in their transition from shot to shot. Expertly used, they are invisible and yet provide the narrative with pace, excitement, and variety.

An alternative editing technique, such as, for example, pop promotions, uses hundreds of cuts, disrupted continuity, ambiguous imagery, etc., to deliberately visually tease the audience, and to avoid clear visual communication. The aim is often to recreate the ‘rave’ experience of a club or concert. The production intention is to be interpretative rather than informative.

The restraints of cutting a story to a specific running time, and having it ready for a broadcast transmission deadline, is a constant pressure on the television editor. Often there is simply not enough time to preview all the material in ‘real’ time. Usually material is shuttled though at a fastforward speed stopping only to check vital interview content. The editor has to develop a visual memory of the content of a shot and its position in the reel. One of the major contributions an editor can make is the ability to remember a shot that solves some particular visual dilemma. If two crucial shots will not cut together because of continuity problems, is there a suitable ‘buffer’ shot that could be used? The ability to identify and remember the location of a specific shot, even when spooling and shuttling, is a skill that has to be learnt in order to speed up editing.

Solving continuity problems is one reason why the location production unit need to provide additional material to help in the edit. It is a developed professional skill to find the happy medium between too much material that cannot be previewed in the editing time available, and too little material that gives the edit no flexibility of structure, running time, or story development changes between shooting, and editing the material.

Repeating a shot of a distinctive group of trees can be used to indicate location and time passing.

The editing techniques used for cutting fiction and factual material are almost the same. When switching on a television programme mid-way, it is sometimes impossible to assess from the editing alone if the programme is fact or fiction. Documentary makers use story telling techniques learned by audiences from a life time of watching drama. Usually, the indicator of what genre the production falls into is gained from the participants. Even the most realistic acting appears stilted or stylized when placed alongside people talking in their own environment. Another visual convention is to allow ‘factual’ presenters to address the lens and the viewer directly, whereas actors and the ‘public’ are usually instructed not to look at camera.

![]() Communication and holding attention: The primary aim of editing is to provide the right structure and selection of shots to communicate to the audience the programme maker’s motives for making the programme, and secondly, to hold their attention so that they listen and remain watching.

Communication and holding attention: The primary aim of editing is to provide the right structure and selection of shots to communicate to the audience the programme maker’s motives for making the programme, and secondly, to hold their attention so that they listen and remain watching.

![]() Communication with the audience: Good editing technique structures the material and identifies the main ‘teaching’ points the audience should understand. A crucial role of the editor is to be audience ‘number one’. The editor will start fresh to the material and he/she must understand the story in order for the audience to understand the story. The editor needs to be objective and bring a dispassionate eye to the material. The director/reporter may have been very close to the story for hours/days/weeks – the audience comes to it new and may not pick up the relevance of the setting or set-up if this is spelt out rapidly in the first opening sentence. It is surprising how often, with professional communicators, that what is obvious to them about the background detail of a story, is unknown or its importance unappreciated by their potential audience. Beware of the ‘I think that is so obvious we needn’t mention it’ statement. As an editor, if you do not understand the relevance of the material, say so. You will not be alone.

Communication with the audience: Good editing technique structures the material and identifies the main ‘teaching’ points the audience should understand. A crucial role of the editor is to be audience ‘number one’. The editor will start fresh to the material and he/she must understand the story in order for the audience to understand the story. The editor needs to be objective and bring a dispassionate eye to the material. The director/reporter may have been very close to the story for hours/days/weeks – the audience comes to it new and may not pick up the relevance of the setting or set-up if this is spelt out rapidly in the first opening sentence. It is surprising how often, with professional communicators, that what is obvious to them about the background detail of a story, is unknown or its importance unappreciated by their potential audience. Beware of the ‘I think that is so obvious we needn’t mention it’ statement. As an editor, if you do not understand the relevance of the material, say so. You will not be alone.

![]() Holding their attention: The edited package needs to hold the audience’s attention by its method of presentation (e.g. method of story telling – what happens next, camera technique, editing technique, etc.). Pace and brevity (e.g. no redundant footage), are often the key factors in raising the viewers’ involvement in the item. Be aware that visuals can fight voice-over narration. Arresting images capture the attention first. The viewer would probably prefer to ‘see it’ rather than ‘hear it’. A successful visual demonstration is always more convincing than a verbal argument – as every successful salesman knows.

Holding their attention: The edited package needs to hold the audience’s attention by its method of presentation (e.g. method of story telling – what happens next, camera technique, editing technique, etc.). Pace and brevity (e.g. no redundant footage), are often the key factors in raising the viewers’ involvement in the item. Be aware that visuals can fight voice-over narration. Arresting images capture the attention first. The viewer would probably prefer to ‘see it’ rather than ‘hear it’. A successful visual demonstration is always more convincing than a verbal argument – as every successful salesman knows.

![]() Selection: Editing, in a literal sense, is the activity of selecting from all the available material and choosing what is relevant. Film and video editing requires the additional consideration that selected shots spliced together must meet the requirements of the standard conventions of continuity editing.

Selection: Editing, in a literal sense, is the activity of selecting from all the available material and choosing what is relevant. Film and video editing requires the additional consideration that selected shots spliced together must meet the requirements of the standard conventions of continuity editing.

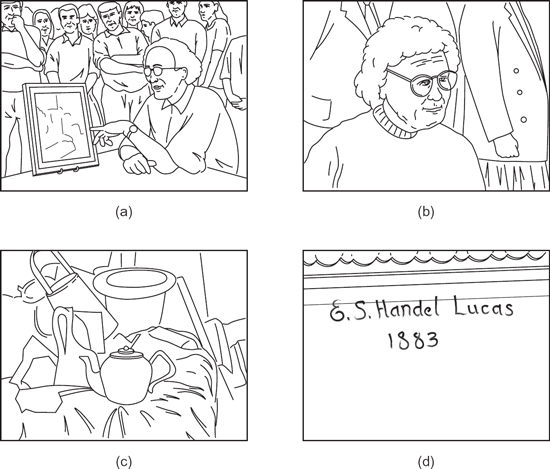

A cutaway literally means to cut away from the main subject (a) either as a reaction to the event, e.g. cutting to a listener reacting to what a speaker is saying (b), or to support the point being made.

A cut-in usually means to go tighter on an aspect of the main subject. For example, an art expert talking in mid-shot (a) about the detail in a painting would require a cut-in close shot of the painting (c) to support the comment, and an even closer shot (d), to see a signature for the item to make sense to the viewer.

Stings and Bridges

Sometimes there is a requirement for a visual and sound bridge between two distinct sequences that nevertheless need to be connected. For example, a roundup of all sporting activity that has taken place over a weekend may have several different sports activities that are to be shown together in one package. Between each separate sporting activity, a bridging graphic or visual with a sound ‘sting’ (a short self-contained piece of music lasting no more than 5 seconds), will be spliced in. The bridging visual can be repeated on each change of topic in the report, and can be, for example, the tumbling last frame of the end of one activity introducing the next activity or possibly a customized digital video effect.

The strongest way of engaging the audience’s attention is to tell them a story. In fact, because film and television images are displayed in a linear way – shot follows shot – it is almost impossible for the audience not to construct links between succeeding images whatever the real or perceived relationships between them. Image follows image in an endless flow over time and inevitably the viewer will construct a story out of each succeeding piece of information.

The task of the director/journalist and editor is to determine what the audience needs to know, and at what point in the ‘story’ they are told. This is the structure of the item or feature and usually takes the form of question and answer or cause and effect. Seeking answers to questions posed, for example, ‘what are the authorities going to do about traffic jams?’ or ‘what causes traffic jams?’, involves the viewer and draws them into the ‘story’ that is unfolding. Many items can still be cut following the classical structure of exposition, tension, climax, and release.

The story telling of factual items is probably better served by the presentation of detail rather than broad generalizations. Which details are chosen to explain a topic is crucial both in explanation and engagement. Many issues dealt with by factual programmes are often of an abstract nature which at first thought, have little or no obvious visual representation. Images to illustrate topics such as inflation can be difficult to find when searching for precise representations of the diminishing value of money. The camera must provide an image of something, and whatever it may be, that something will be invested by the viewer with significance.

That significance may not match the main thrust of the item and may lead the viewer away from the topic. Significant detail requires careful observation at location, and a clear idea of the shape of the item when it is being shot. The editor then has to find ways of cutting together a series of shots so the transitions are seamless, and the images logically advance the story. Remember that the viewer will not necessarily have the same impression or meaning from an image that you have invested in it. A shot of a doctor on an emergency call having difficulty in parking, chosen, for example, to illustrate the problems of traffic congestion, may be seen by some viewers as simply an illustration of bad driving.

Because the story is told over time, there is a need for a central motif or thread which is easily followed and guides the viewer through the item. A report, for example, on traffic congestion may have a car driver on a journey through rush hour traffic. Each point about the causes of traffic congestion can be illustrated and picked up as they occur such as out-of-town shoppers, the school run, commuters, traffic black spots, road layout, etc. The frustrations of the journey throughout the topic will naturally link the ‘teaching’ points, and the viewer can easily identify and speculate about the story’s outcome.

Emphasis, Tempo and Syntax

Just as a written report of an event will use a structure of sentence, paragraph and chapter, a visual report can structure the elements of the story telling in a similar way. By adjusting the shot length and fine tuning the rate and rhythm of the cuts, and the juxtaposition of the shots, the editor can create emphasis and significance.

A piece can be cut to relate a number of connected ideas. When the report moves on to a new idea there is often a requirement to indicate visually, ‘new topic’. This can be achieved by a very visible cut – a mismatch perhaps, or an abrupt change of sound level, or content (e.g. quiet interior is followed by a cut to a parade marching band), to call attention to a transitional moment.

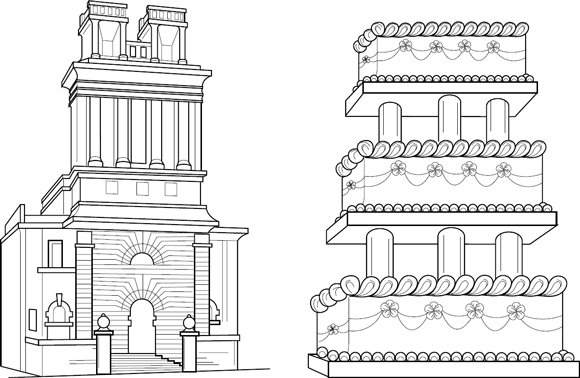

Attention can also be captured by a very strong graphic match, usually in a dissolve, where the outgoing shot has, for example, the strong shape of the architecture of a church, which has substantial columns converging up to a dome which is mixed to a shot of a similar shaped wedding cake, matched in the same frame position and lens angle. The audience registers the visual connection because the connection has been overstated. The visual design match is so strong it becomes visible, and signals a change of time, place, or a new scene or topic.

The chosen structure of a section or sequence will usually have a beginning, a development, and a conclusion. Editing patterns and the narrative context do not necessarily lay the events of a story out in simple chronological order. For example, there can be a ‘tease’ sequence which seeks to engage the audience’s attention with a question or a mystery. It may be some time into the material before the solution is revealed, and the audience’s curiosity is satisfied. Whatever the shape of the structure it usually contains one or more of the following methods of sequence construction:

![]() A narrative sequence is a record of an event such as a child’s first day at school, an Olympic athlete training in the early morning, etc. Narrative sequences tell a strong story and are used to engage the audience’s interest.

A narrative sequence is a record of an event such as a child’s first day at school, an Olympic athlete training in the early morning, etc. Narrative sequences tell a strong story and are used to engage the audience’s interest.

![]() A descriptive sequence simply sets the atmosphere or provides background information. For example, an item featuring the retirement of a watchmaker, may have an introductory sequence of shots featuring the watches and clocks in his workshop before the participant is introduced or interviewed. Essentially, a descriptive sequence is a scene setter, an overture to the main point of the story, although sometimes it may be used as an interlude to break up the texture of the story, or act as a transitional visual bridge to a new topic.

A descriptive sequence simply sets the atmosphere or provides background information. For example, an item featuring the retirement of a watchmaker, may have an introductory sequence of shots featuring the watches and clocks in his workshop before the participant is introduced or interviewed. Essentially, a descriptive sequence is a scene setter, an overture to the main point of the story, although sometimes it may be used as an interlude to break up the texture of the story, or act as a transitional visual bridge to a new topic.

![]() An explanatory sequence is, as the name implies, a sequence which explains either the context of the story, facts about the participants or event, or explains an idea. Abstract concepts like a rise in unemployment usually need a verbal explanatory section backed by ‘visual wallpaper’ – images which are not specific or important in themselves, but are needed to accompany the important narration. Explanatory sequences are likely to lose the viewer’s interest, and need to be supported by narrative and description. Explanatory exposition is often essential when winding-up an item in order to draw conclusions or make explicit the relevance of the events depicted.

An explanatory sequence is, as the name implies, a sequence which explains either the context of the story, facts about the participants or event, or explains an idea. Abstract concepts like a rise in unemployment usually need a verbal explanatory section backed by ‘visual wallpaper’ – images which are not specific or important in themselves, but are needed to accompany the important narration. Explanatory sequences are likely to lose the viewer’s interest, and need to be supported by narrative and description. Explanatory exposition is often essential when winding-up an item in order to draw conclusions or make explicit the relevance of the events depicted.

The Shape of a Sequence

The tempo and shape of a sequence, and of a number of sequences that may make up a longer item, will depend on how these methods of structuring are cut and arranged. Whether shooting news or documentaries, the transmitted item will be shaped by the editor to connect a sequence of shots either visually, by voice-over, atmosphere, music, or by a combination of any of them. Essentially the cameraman or director must organize the shooting of separate shots with some structure in mind. Any activity must be filmed to provide a sufficient variety of shots that are able to be cut together following standard editing conventions (e.g. avoidance of jump cuts, not crossing the line, etc.), and that there is enough variety of shot to allow some flexibility in editing. Just as no shot can be considered in isolation, every sequence must be considered in context with the overall aims of the production.

Building a Structure

Creating a structure out of the available material will tell a story, present an argument, or provide a factual account of an event (or all three). It starts with a series of unconnected shots which are built into small sequences. These are then grouped into a pattern which logically advances the account either to persuade, or to provide sufficient information leaving the viewer to draw their own conclusion. Usually the competing points-of-view are underlined by the voice-over, but a sequence of strong images will make a greater impact than words.

The available material that arrives in the edit suite has to be structured to achieve the clearest exposition of the subject. Also the edited material has to be arranged to find ways of involving the viewer in order to hold their interest and attention. Structure is arranging the building blocks – the individual unconnected shots – into a stream of small visual messages that combine into a coherent whole.

For example, a government report on traffic pollution is published which claims that chest ailments have increased, many work hours are lost though traffic delay, and urges car owners to only use their vehicles for essential journeys.

A possible treatment for this kind of report would be to outline the main points as a voice-over or text graphic, interviews with health experts, motorist pressure group spokesman, a piece to camera by the reporter, and possibly comments from motorist. The cameraman would provide shots of traffic jams, close-ups of car exhausts, pedestrians, interviews, etc. The journalist would decide the order of the material whilst writing his/her voice-over script, whilst the editor would need to cut bridging sequences which could be used on the more ‘abstract’ statistics (e.g. increase in asthma in children, etc.). Essentially these montages help to hold the viewer’s attention and provide visual interest on what would otherwise be a dry delivery of facts. A close-up of a baby’s face in a pram cut alongside a lorry exhaust belching diesel fumes makes a strong quick visual point that requires no additional narrative to explain. The juxtaposition of shots, the context and how the viewer reads the connections is what structures the item, and allows the report to have impact. The production team in the field must provide appropriate material, but the editor can find new relationships and impose an order to fit the running time.

News reportage attempts to emphasize fact rather than opinion, but journalistic values cannot escape subjective judgements. What is news-worthy? What are news values? These questions are answered and shaped by the prevailing custom and practices of broadcasting organizations. Magazine items can use fact, feeling, atmosphere, argument, opinion, dramatic reconstruction, and subjective impressions. These editing techniques differ very little from feature film storytelling. For a more detailed account of objective and subjective reporting, see the section on documentaries.

News – Condensing Time

A news bulletin will have a number of news items which are arranged in importance from the top story down through the running order to less important stories. This running order, compiled by the news editor, will usually allow more time to the main stories, and therefore the editor and journalist will often face the task of cutting an item to a predetermined time to fit the news agenda. There are a number of ways of chopping time out of an item. If a voice-over script has been prepared to the running time allocated, the editor can use this as a ‘clock’ to time the insertion of various images throughout the piece. The task then is to slim down the selection from the available material to a few essential images that will tell the story. It is a news cameraman’s complaint that when the editor is up against a transmission deadline, he/she will only quickly preview the first part of any cassette, often missing the better shots towards the end of the tape. If there is time, try to spin through and review all the material. The cameraman can help the editor, wherever possible, by putting interviews on one tape and cutaways and supporting material on another cassette. This allows the editor to quickly find material without shuttling backwards and forwards on the same tape.

News – Brevity and Significance

The pressure of cutting an item down to a short duration will impose its own discipline of selecting only what is significant and the shots that best sum up the essence of the story. The viewer will require longer on-screen time to assimilate the information in a long shot than the detail in a close shot. Moving shots require more perceptual effort to understand than static shots.

The skill in news cutting can be summed up as:

![]() each shot must serve a purpose in telling the story

each shot must serve a purpose in telling the story

![]() more detail than geography shots or scene setting

more detail than geography shots or scene setting

![]() more close, static shots than ones with camera movement

more close, static shots than ones with camera movement

![]() use short pans (no more than two seconds long) to inject pace into a story

use short pans (no more than two seconds long) to inject pace into a story

![]() use a structure containing pace, shot variety, and dynamic relevant images.

use a structure containing pace, shot variety, and dynamic relevant images.

Unscripted Shot Structure

Most news and magazine items will not be scripted when they are shot. There may be a rough treatment outlined by the presenter or a written brief on what the item should cover, but an interview may open up new aspects of the story. Without pre-planning or a shot list, the shots provided will often revert to tried and trusted formulas. A safe rule-of-thumb is to move from the general to the particular – from wide shot to close up. A general view (GV) to show relationships, and to set the scene, and then to make the important points with the detail of close-ups. The cameraman has to provide a diversity of material to provide cutting points. The editor will hope that the cameraman/journalist has provided:

![]() a substantial change in shot size or camera angle/camera position for shots intended to be intercut

a substantial change in shot size or camera angle/camera position for shots intended to be intercut

![]() a higher proportion of static shots to camera movement. It is difficult to cut between pans and zooms until they steady to a static frame and hold

a higher proportion of static shots to camera movement. It is difficult to cut between pans and zooms until they steady to a static frame and hold

![]() relevant but non-specific shots so that voice-over information (to set the scene or the report) can be dubbed on after the script has been prepared

relevant but non-specific shots so that voice-over information (to set the scene or the report) can be dubbed on after the script has been prepared

Cutting a Simple News Item

![]() The journalist previews the material (if there is time).

The journalist previews the material (if there is time).

![]() Decide whether the item will be cut to picture or audio.

Decide whether the item will be cut to picture or audio.

![]() Cutting to audio: the journalist writes the script identifying where interviews and essential visuals will occur.

Cutting to audio: the journalist writes the script identifying where interviews and essential visuals will occur.

![]() The journalist records the voice-over (v/o) in the dub studio or if time is against him, or the dub studio is in use, records off a lip mic in the edit suite.

The journalist records the voice-over (v/o) in the dub studio or if time is against him, or the dub studio is in use, records off a lip mic in the edit suite.

![]() The VT editor then lays down as much audio that is available, e.g. v/o, interviews, etc., and then cuts pictures to the sound.

The VT editor then lays down as much audio that is available, e.g. v/o, interviews, etc., and then cuts pictures to the sound.

![]() Atmos or music may be added after this cut.

Atmos or music may be added after this cut.

![]() Cutting to picture: Load the correct cassette and jog and shuttle to find the start of the first shot.

Cutting to picture: Load the correct cassette and jog and shuttle to find the start of the first shot.

An Appropriate Shot

Every shot should be recorded for a purpose. That purpose is at its weakest if it simply seemed a good idea at the time to the cameraman or director etc., to record a shot ‘just in case’ without considering its potential context. No shot can exist in isolation. A shot must have a connection with the aim of the item and its surrounding shots. It must be shot with editing in mind. This purpose could be related to the item’s brief, script, outline, or decided at the location. It could follow on from an interview comment or reference. It could be shot to help condense time or it could be offered as a ‘safety’ shot to allow flexibility in cutting the material.

The interview is an essential element of news and magazine reporting. It provides for a factual testimony from an active participant similar to a witness’s court statement; that is, direct evidence of their own understanding, not rumour or hearsay. They can speak about what they feel, what they think, what they know, from their own experience. An interviewee can introduce into the report opinion, beliefs and emotion as opposed to the reporter who traditionally sticks to the facts. An interviewee therefore provides colour and emotion into an objective assessment of an event and captures the audience’s attention.

How Long Should a Shot be Held?