6. Shooting Tips from the Pros

One of the aspects of photography that makes it so interesting and that keeps us engaged over a lifetime is that there is just so much to learn. Digital has made photography much more accessible due to the instantaneous feedback it provides, but digital has also brought additional layers of complexity as well as new tools to learn. I have to assume that you wouldn’t be holding this book if you weren’t already holding a camera, but that simple fact alone doesn’t tell me much about what you already know about photography, or which photographic paths you want to follow. My primary focus in this book is to help you build a foundation for success in microstock, while helping you overcome many of the stumbling blocks encountered by all those who have gone before you. I simply cannot teach you everything you need to know about shooting every type of subject under every set of conditions.

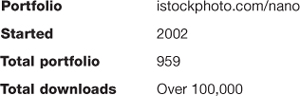

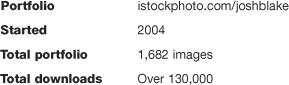

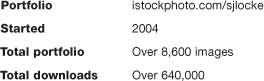

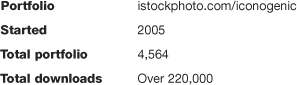

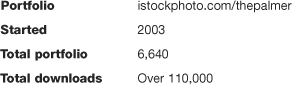

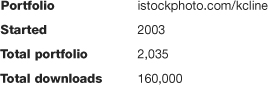

However, there are shooting skills and knowledge—such as the importance of getting a proper exposure; how to use your camera’s built-in computer to help analyze exposure; and knowing the important tasks required before, during, and after any type of photo shoot you encounter—that will continue to build that foundation. In addition, I want to expose you to some of the most successful microstock contributors I know. There are contributor profiles throughout every chapter of the book that provide excellent tips, but for this chapter I dug a little deeper with seven top contributors, whose combined lifetime download total is nearly 1.5 million, to get some of the shooting tips that have served them well along the way.

Figure 6.1. Photographer. © Joan Vicent Cantó Roig

The Importance of Good Exposure

Focus and exposure, if done poorly, are two factors that almost always guarantee rejection. Either a shot is in focus or it is not, and when it is not, the only recourse is to refocus and reshoot.

When it comes to exposure, it is not as clear-cut because of what is possible to adjust in post-production. While it is true that when shooting in RAW mode (and to a much lesser extent in JPEG mode) you have a bit of latitude to correct minor exposure problems (which we’ll cover in Chapter 8), it is also true that the greater the corrections needed to fix exposure in post-production, the more likely you are to increase the visibility of noise or simply end up with a very overprocessed-looking photo. Remember, image inspectors are going to evaluate your photos at 100 percent (or 1:1 view), which is much less forgiving of technical flaws than you may be on your own screen.

Why give yourself less material to work with if you don’t have to? Nailing a proper exposure is really all about capturing as much of the data as possible in a given scene. The light metering capabilities of digital cameras continue to improve, but it is still up to the human operator to evaluate the exposure of each capture.

Reading the Histogram

Every digital camera is also a computer. One of the functions of your computer-camera is to arrange all the pixels in a given capture according to their brightness levels, from shadows (black) to highlights (white), and display them in a graph, called the histogram (Figure 6.3), that makes it easy to see at a glance on the camera’s LCD screen where the majority of the brightness values happen to be, and where there aren’t any at all. The distribution of these brightness values is called the tonal range. When used in conjunction with the actual captured photo, the histogram can help us evaluate if we exposed that scene in such a way as to have avoided losing any important data. Understanding the nature of the histogram now will also help when you see it later in your image editing software.

Figure 6.3. The histogram displays the pixels in your photo arranged from darkest on the left to brightest on the right.

Note

It is important to know that the in-camera histogram is based on the in-camera settings used to create a JPEG even if you are shooting in RAW mode.

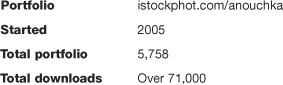

There is no single good histogram for all scenes, and the goal is not to get the best-looking histogram. The goal is always to maximize the capture of the important visual data in the scene. Let’s look at some examples. Here are three photos, taken within a span of two minutes, along with the histogram for each. This is a scene where due to the partly cloudy sky and fast-moving clouds, the intensity of the light was changing quickly. The first photo (Figure 6.4) is overexposed and potentially has lost a lot, if not all, detail in the brightest highlights of the water. Notice how its histogram shows the highest number of brightness levels stacked up against the right edge, and almost no brightness levels on the left edge.

Figure 6.4. This photo is overexposed and potentially losing highlight detail. The histogram is stacked up on the right edge.

Note

You may need to consult the manual on this one if you don’t know how to find the histogram on your camera.

In the second photo (Figure 6.5), I attempted to change my exposure settings to prevent overexposure, but went a little too far, and the result is slightly underexposed. Notice how the entire tonal range shifted to the left, pulling completely away from the right edge.

Figure 6.5. This photo is slightly underexposed. The highlight detail is captured, but recovering detail in the darker areas is likely to make existing noise more visible.

In the third photo (Figure 6.6), I readjusted my exposure settings. The light cooperated by not changing, and I was able to produce an exposure that was just right. By “just right” I mean the tonal range is distributed across the entire histogram, showing pixels in the shadows, midtones, and highlights, and while there are peaks in the highlight area of the graph, this is to be expected due to the amount of white water in the scene. I am fairly confident from looking at both the photo in Figure 6.6 and its histogram together that I can recover all important highlight data that may appear at first to be lost, while still retaining nice detail in the midtones and shadows, and overall good contrast.

Figure 6.6. This photo is properly exposed for the scene. Highlight data is recoverable, and the wide distribution of tones across the histogram suggests adequate data at all brightness levels.

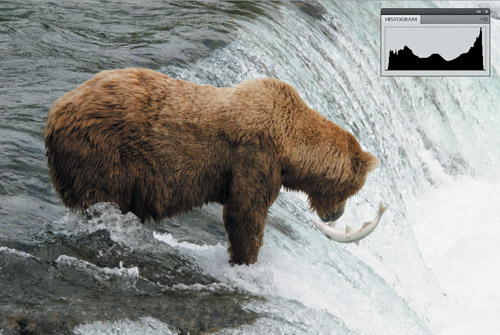

Some photos, because of the subject matter, will have a histogram that weighs heavily toward one end or the other of the tonal range without it being wrong. For example, the photo (Figure 6.7) of a single candle flame in an otherwise dark room has a histogram completely stacked up against the left edge (dark room), with just a tiny thin peak of a spike on the right (candle flame). That is the correct exposure for that scene. Similarly, you would expect that a photo of a small black ball on a pure white background would have most of its brightness levels stacked up on the right side (white background), with a small peak on the left (black ball). The detail in the photo is what matters most, and the histogram is just a tool to help you evaluate that when all you have is a small camera LCD screen, and the time to shoot is now.

Figure 6.7. It is expected that a scene composed almost entirely of black regions would have a histogram stacked to the left.

Highlight Clipping Warning

In addition to the histogram, most digital cameras have a highlight clipping warning indication mode, commonly called the blinkies, because when it is turned on, any blown-out highlight area within the photo will blink on the LCD screen. I often find myself using this indicator first, and if there is no blinking and the photo otherwise looks well exposed, I’ll just keep on shooting. At the first sign of blinking in an important highlight area, I’ll switch to the histogram to try to evaluate if the overexposure is too great. For example, if you are shooting a scene that contains a highly reflective surface, like a chrome bumper, then you would expect to see some blown highlights in any reflections of the light source. However, if you are seeing that the white shirt of your subject is blinking then you need to evaluate the situation and change your exposure settings accordingly to preserve that important detail.

Note

As with histograms, you may need to consult the manual for your particular camera on highlight clipping warning as well.

The key point to keep in mind when shooting is that if you nail focus and exposure, and can create a compelling and useful composition, then you’ve got a keeper on your hands, and that is what it is all about. It is always in your best interests to start with the best-quality capture possible, and not just hope you can fix it later in post-processing.

Top Tips for Your Next Photo Shoot

There’s nothing wrong with a photo shoot that consists of simply grabbing your camera and walking out the door, but there are a number of ways to increase the chances of creating stock-worthy content, regardless of the subject matter. Put a little more thought and effort into each stage in the process, from preparing for the shoot, to the actual shooting day, and all the tasks needed at the end to wrap up successfully.

Get Ready

Over the years, I’ve noticed that one of the biggest factors that separates the pros from the rest is how much work the pros do before they even pick up the camera. Here are five tips to help you get to the top of your game:

- Create a shoot list.

This is all about pre-visualizing the themes, concepts, and ideas you want to communicate in your photos from a given shoot. Some people go so far as to create storyboards, which are a series of sketches that depict all the scenes they want to capture. I asked Josh Blake (profiled on page 78) about about his practice. “I usually draw a few hand sketches of what I’m looking for in the shoot. I also write down the main shots that I know I want to get for sure, otherwise I get so wrapped up in the shot, and getting the lighting right, and changing props/costumes/makeup, that I forget to get that one shot that I was really thinking would look cool if I tried,” he says.

Kelly Cline (profiled on page 90) adds, “It really helps to keep the shoot on track which maximizes the potential volume of output and usefulness of a particular item. This is especially true with food, since food has a tendency to have a very short life in front of the camera before it starts to droop, congeal, or wither. You really have to do everything you can to maximize your time.”

- Communicate with your models and team members well in advance.

I know that for most of us, photography can be a one-person operation most of the time. As you grow and want to reach the next level, it’s likely going to involve more people in the form of models, stylists (for food, people, animals, and even objects), and assistants. In those cases, be sure to send out multiple emails in advance of the shoot to provide information on the dates, times, locations, and requirements for a given shoot. Sean Locke (profiled on page 80), who works almost exclusively with models these days, says, “I make sure to send out several emails before the shoot, reminding them of the date/time, and what they are supposed to bring/wear. I also include the model release with the email, so they can get it signed ahead of time.”

- Scout the location.

When you first have a concept or a theme in mind, it may require a specific location to make it work. Give yourself plenty of time to explore your surroundings and find that perfect spot, and get permission if needed. The location could be just the ingredient to add the level of authenticity to your shoot that puts it head and shoulders above the competition. Once you’ve got a location nailed down, be sure to pay it another visit a few days before the shoot to make sure nothing has changed that can affect your goals. Nancy Louie (profiled earlier in this chapter) had this excellent advice to offer: “Look immediately for problems. I note large mirrors or highly reflective areas or large objects that cannot be moved. Look for adequate space for the angles you want to shoot, and that there is room for the type of lighting you will use. I always try to scout at the time of day that I’d be shooting for both indoors and out. Always look for the electric outlet locations in the space.”

- Assemble the gear.

In the 24 hours before the actual shoot, you want to use your shoot list to help gather all the gear you are going to need to get those shots, with that location in mind. This is the time to check that batteries are charged, memory cards are formatted, additional fresh batteries are on hand, and you have the specific camera body, tripod, stands, lenses, and lighting tools your shoot list requires. Do you have a backup camera body? Maybe not at the start of your career, but the next time you upgrade your camera, hold on to the old one as a backup. Make a checklist of all the gear you need, and check it twice. This list will serve as a reminder when you return, and check all the gear back in.

- Reset the camera settings to a neutral state.

I’m sure that like me, you are using your camera for all sorts of subjects and conditions. Hopefully, you are even experimenting and trying new things. Be sure to add in the pre-production step of loading your camera with a fresh battery and memory card, and firing a few test shots the night before. Check all your key camera settings, such as your ISO, white balance, metering mode, and image quality. Heaven forbid there is a technical problem with the gear, but better to know now than when you are on location.

Wrap it up with a good night’s sleep so you are at your freshest mental state, which should help reduce simple mistakes and oversights on shooting day.

Day of the Shoot

Starting this day fresh, with all your prep work done, is going to help you get the most in terms of quality and quantity when it comes time to shoot. Here are five more tips to help you take it to the next level:

- Double-check your gear before you walk out the door.

If you did your homework the night before, then this should be a quick confirmation that everything is as it should be. This is just too important to not take the extra five minutes to make sure you did in fact put the camera back in the bag after checking all the settings. Don’t forget your shoot list either.

- Prepare the scene.

You did the scouting, so you know right where to go. Whether it is just you and the great outdoors, or you’ve got a dozen models showing up in half an hour, take the time now to clear away distractions and set the stage. This is also a good time to be thinking about alternative options. Kelly Cline told me that she is always “making sure that I have a ‘Plan B’ in the event that an idea does not pan out or proves to be too difficult to execute.” Things always go wrong on some level, but it is the pros who are prepared to roll with the punches and keep on shooting.

- Change things up.

While your shoot list serves as an overall guide, take the time to mix up the angles you are shooting from, go high, go low, move way in, and move out. Shoot both horizontals and verticals. It is too easy, especially if you are using a tripod, to get locked into one way of shooting. Loosen that tripod up and shoot a vertical after each horizontal. You never know which angle may prove to be the most useful to your prospective customers. Once you’ve gotten everything on your list, and there is still time, circle back to any inspirations you had during the day and see what you come up with.

- Do spot checks.

It is easy to get caught up in the shooting, and there’s nothing wrong with that. Make yourself take time to spot-check the obvious things such as focus and exposure, but also on the less obvious such as the background. Is the background helping to communicate your intended message? Is it too busy, too bright, too dark? Are you noticing any problematic content that it would be easier to remove from the scene than to remove with software later? Did you brush all the lint off the model’s clothing? Would a little burst of compressed air clear the bugs off that flower? Did you wipe down all the important objects with a lint-free cloth to remove the dust? Attention to detail is another factor that separates the pros from the pack.

- Have fun!

Pulling this off can be a lot of work, so be sure to build in breaks for yourself and your subjects. Having food and water on hand keeps everyone refreshed and in a good mood. If the situation allows, have some music playing in the background. Bring some crazy props that you may not even use, but could be just the thing to change an expression, or create a mood that is fun and lighthearted.

At the end of the day, if you’ve remained true to your vision, you’ll not only have a lot of quality content to work with, but you’ll feel satisfied by having had a great time making it happen.

After the Shoot

Whether you were shooting in your spare bedroom, an abandoned factory, the great outdoors, or a studio, there are a few things you want to make sure you always do to put a successful wrap on your shoot.

1. Clean up.

Ugh. OK, easily the least sexy part of the entire process, but think of it more like helping you get set back up for the next shoot. You may have a location to put back together, so do it right so that you’ll be allowed to come back in the future. You may have props to clean up and put away. Use the gear list you made the night before and check all your gear back in to be sure you didn’t leave anything behind. Give your camera and lenses a wipe down on the outside, and learn how to clean your image sensor to keep it free of dust bunnies.

2. Back up your photos.

Arguably this could come before doing any cleanup, but it really will depend on where you are when you were shooting, and what the subject matter happened to be. If you were shooting in your home or studio, then getting the backup started while you put things away works well. If you are on location and have a portable drive or laptop, then there is nothing wrong with multi-tasking by getting a backup going as you pack up the gear. Otherwise, this should be the first thing you do when you get home.

3. Don’t forget the paperwork.

Did I say clean up was the least sexy? This is a close contender. However, if you were working with models, be sure to collect all signed (and witnessed) releases before you let them leave the location (best to do on arrival, so no one gets away by mistake). Make a practice of taking a photo of the model holding the release. This helps you remember who is who, and serves as one more bit of proof that they did sign the release.

After your photos are safely backed up, take a moment to enjoy all the work you did with a judgment-free review. You know you want to see them, so make this pass a focus on ensuring the backup is complete, the photos are corruption free, and you got all the shots on your list. Once you’ve confirmed all of this, it is safe to format those memory cards for the next shoot.

5. Unwind.

You just worked your butt off, and as much as you may have enjoyed it, do yourself a favor and decompress. Turn off the computer, stow the gear, and turn out the lights on your way out. I say this as someone who has burned the midnight oil one too many times. Eat a good meal, spend time with your loved ones, and do something that doesn’t involve a glowing screen. You earned it.

Moving Forward

It has been my experience that the majority of microstock contributors are highly motivated self-directed learners. We learn from each other as well as from books, websites, and classes. This really is a lifelong process, and you will have many teachers along the way. There are two resources in particular that I have found so valuable that I made it a goal to find ways to get to work for both of them (and I did).

The first, and the one that I have gained the most from over the years, is the National Association of Photoshop Professionals. For an annual membership fee of $99 (at this writing), you gain access to a tremendous amount of training—covering photography, Photoshop, and Lightroom—both online and in print (Photoshop User Magazine); a very active member’s online forum; and unlimited Photoshop, Lightroom, and photography gear Help Desk support. But what might be most valuable of all are the fantastic discounts on gear, training, and equipment from all the top vendors in the industry. You’ll easily recoup your membership fee in no time at all. Head over to www.photoshopuser.com to learn more.

Many years ago, when I was first getting started in shooting for stock I picked up the book called Understanding Exposure, by Bryan Peterson (Amphoto Books), and the lights finally came on. I’ve recommended this book to everyone who has ever asked me what book they should get to help their photography. In 2009, I was researching online photography schools that could be a good fit for a Lightroom class I had in mind. When I discovered that Bryan Peterson founded his own school, called the Perfect Picture School of Photography (www.ppsop.com), I was immediately intrigued. What sold me on the school, though, was the fact that there is a lot of room for interaction between instructors and students, which is a real challenge in online training. PPSOP, as it is called, offers a wide variety of photography classes, ranging from 4- to 12-week sessions. If you are looking for an extremely accessible, yet structured, approach for expanding your photography skills, this is a good place to start.

Figure 6.14. I write for Photoshop User Magazine and staff the Lightroom Help Desk for NAPP, and teach a Lightroom class at PPSOP.