Chapter 2

Offensive vs. Defensive Attacker Mindset

Before we dive into the components of the mindset, it is worthwhile to categorize it into its offensive and defensive sides. In this chapter, we will briefly look at what offensive and defensive security is and how they differ from each other. Then we will look at the offensive and defensive side of the mindset and what each side brings to its security counterpart in terms of skill and functionality.

Many millions of dollars in public and private investment have been spent on new technologies, usually for defensive measures rather than offensive. Offensive security is a proactive and an oppositional approach to protecting computer systems, networks, and individuals from attacks. The offensive part of the attacker mindset is also oppositional and dogged.

Defensive security, however, uses a reactive approach that focuses on prevention and detection of attacks. The defensive mode of your AMs will allow you to be reactive, helping you see ways in which you might be caught and hopefully circumventing those defenses with the help of your offensive prowess. Afterward, your defensive AMs will allow you to see ways to prevent attacks, making you extremely valuable to any client.

In terms of technology, currently there is an enormous defensive preference in security. Unfortunately, this means that the time between a defensive weapon's creation in comparison to that of its offensive counter is often huge. Another problem with this defensive preference is that even with the best defensive security protocols and technologies in place, as a social engineer or red teamer, there is a chance I'll be able to slip right past them, which is often a lot easier than getting past a technological defensive protection and can be just as damaging, maybe more so. Additionally, technology is becoming further and further intertwined throughout the broad population's professional and personal lives, which makes the overall goal of security more complex. Because of this, both sides of technology are needed and both sides of the mindset are needed.

Both offensive and defensive securities have their purpose, and each is important from a business standpoint. Offensive cybersecurity strategies shrink the chance of attacks by promoting a permanent state of readiness and actively analyzing the environment; they can and should be critical in keeping people like me out, which is a big win when undergoing testing, and the malicious digital pentesters, too.

Defensive security relies on a comprehensive understanding of an environment and being able to analyze it in order to detect latent flaws. The barrier to perpetual, effective defensive security is the inability to always accurately predict the future.

A like-for-like scenario might be that of an earthquake. In the United States, we construct buildings meant to withstand earthquakes within a range of magnitude, but we can't always accurately predict all the other chaos, mayhem, and destruction it might bring with it. So, after a hurricane strikes, the clean-up begins and measures like riverbank management are put in place so that the situation is not repeated in the future. However, the next earthquake that strikes might do unforeseen damage to other critical infrastructure. So, that is then hardened, and the loop continues. As an example, Hurricane Sandy, when it hit New York in 2012, shone a light on the inherent flaws of keeping generators in basements. When flooded, generators are relegated from use. The aftermath of Hurricane Sandy also saw the city build more emergency shelters, repair public housing to make it more storm-resistant, and construct flood protection in the form of greenery around Manhattan. City officials estimate that the storm cost $19 billion in damages and lost economic activity.

Defensive cybersecurity deals with the prevention of attacks and the strengthening of the defenses that keep them at bay. These defensive measures often follow a successful offensive attack—hence the constant lag and uneven playing field. If a metaphorical hurricane hits a business, they have to quickly address the points of failure, put in place short-term mitigations, and find ways to make their environment more resilient and less vulnerable to malicious damage. That reality means it's imperative for the business to start preparing immediately to protect its employees, infrastructure, and revenue from those future catastrophes.

Offensive security mainly refers to penetration testing, for which a broad definition has been given already, and physical testing, which is a main focus of this book. Threat hunting, which traditionally is the proactive seeking and destroying of cybersecurity threats before they compromise an organization, may also be considered as a form of offensive security. For the purposes of this book, threat hunting is a core component of AMs and, in particular, the offensive part of the mindset; instead of seeking and destroying threats to the company, an ethical attacker (EA) will seek out information or gaps and turn them into threats. It's an alternative way of thinking about threat hunting, and it only applies through the lens of this book and context. The defensive side intersects here because it seeks out defenses to first circumvent them and then, after the attack, to patch and bolster them. Offensive security doesn't just build protections and resistance. It sees pervasive penetrations for what they are—an active form of asymmetric warfare that threatens security at the highest levels. Offensive security thus aims not just to defend against threats, but to neutralize them.

With all that said, it seems fair to say that there are advantages to both sides of security, and that having neither side would result in mayhem for everyone. Technology has a lot to offer to us all now and in the future, but our greatest challenge will always be keeping it all secure. Even the most cutting-edge techniques and methodologies of today will have to evolve in the future, and so part of every business's (and individual's) security strategy needs to be devoted to this task of staying ahead of the curve. Here is where I come to the point: taking all of this into consideration, there is a solid case for an EA to have strong offensive and defensive skills from a mental standpoint. The remainder of this chapter will look at the mental portion of these categories and how they manifest, as well as their function as part of a mindset.

The overview I will start with is this: both are needed, and one cannot exclude the other. The defensive attacker mindset (DAMs) minimizes how long a mitigating control or interference can obstruct you from achieving your objective by identifying defenses. The offensive attacker mindset (OAMs) promotes a permanent state of readiness, allowing constant analyzation of your environment and the ability to detect vulnerabilities and impose costs on those defenses.

The Offensive Attacker Mindset

The offensive attacker mindset (OAMs) allows you as an EA to direct an event in the direction of the objective. More specifically, it allows you insights normally invisible to others (namely defense). It is always scanning for vulnerabilities and creating them from information. OAMs is oppositional and unyielding, and it uses information and environments only to further your position. It does not care about anything outside of its focus, which is always the objective. Typically, your objective as a pentester is access to an asset, information, or place within a building(s) or on a network.

This mindset uncovers a catalog of valuables and vulnerabilities, and not only those you've identified for your own, relatively narrow objective—it also helps you identify what else the target deems important in the moment. It will reveal vulnerabilities that you might not be able to use due to your scope of work or that you've missed because they do not suit your objective but may still be a critical or severe vulnerability. For example, if your objective is to get into the building and to the network operations center (NOC) without using any other entrances or exits other than the front door, you should still note if there are opportunities to do so, whether it be the loading dock or parking structure.

In another example, you may believe due to your scope and objective that the NOC is the thing the company wants to protect most. However, upon entering an environment, you may figure out that actually they are preparing for a market-disrupting move that executives are meeting for, talking about, and writing about. This is valuable information—it doesn't change your scope or objective, but it is worth noting in your report or directly to your point of contact (POC).

OAMs is also what keeps you in a sort of hunt mode as the attack unfolds, identifying any opportunities that present themselves and exploiting them with seeming ease and poise—all without letting the target know that you have any ulterior motive or missing a beat as you deviate from your original plan. It leads you to learn new things about your target and apply those lessons for the good of the objective. For example, you might not learn until you get on-site that they have upgraded their visitor system to a digital kiosk that can be circumvented with the standard out-of-the-box key code.

There is also a sense of competitiveness with OAMs. It doesn't want to be beaten. Ever. It doesn't want to be merciful or helpful. It wants only to win. Your competitive drive is always influenced greatly by your determination to set and achieve goals. It should keep you striving for progress with a quiet but unrelenting focus. It's the peak of your curiosity and persistence combined. It is your competitive desire combined with critical thought that helps you match and surpass defenses meant to stop you. Your OAMs is powerful—a force to be reckoned with, neatly hidden behind a pretext or stealthy moves.

OAMs also guides the achievement of our objective through certain advantageous vectors. It does so by revealing facilitation in places you might not have considered looking otherwise, like vendors, suppliers, insurance providers, and building maintenance contractors. It helps you look at the world in an adversarial and alternative way. It sees through a lens that only identifies helpful or unhelpful data and information. OAMs wants to proceed and succeed. It's the machine that weaponizes information.

Comfort and Risk

My position is this: comfort with risk is one of the most essential offensive skills. Comfort with risk does not equal discomfort with caution, however. Too much discomfort with caution will not serve you in this field.

If you are going out on a mission (say to an armed facility), the risk is in going; you should remain cautious at every step, but, again, too much overt caution in the moment will have you stand out…a surefire way to get shot (no pun intended). For the rest of the operations and engagements you go on, you will need to be comfortable with risk; too much caution in the moment will equate to too little confidence, and this may result in you seeming unnatural, which is the antitheses of your role most often. There are of course times where you will be nervous; my advice is that, in such moments, use those nerves as part of your pretext. Let your nervous energy come out as you tell security that you are running late for a critical meeting.

This position on caution remains valid no matter the vector you are using—being too cautious on a vishing call where the target expects authenticity will likely lower your probability of success. Being cautious with a phish is a thing—it will show up in the length of the email you send. You will likely try to answer every question you can possibly come up with from the target's perspective in the body of your phish—a big no-no. Phishes are to be succinct and not say quite enough, piquing the target's curiosity or piquing some other mood or reaction so that they click on the phish's link. Too much caution on a network pen test will likely prevent you from seeing gaps and exploiting them. You need to be able to take calculated risks.

It's notable that there's a difference between being comfortable with risk and failing to analyze a situation, but OAMs has you strike a balance between the two. The balance can be found in seeking a solution as a problem comes into view. The slight caution that OAMs affords you is what aids the swift identification of a problem. Implementing the solution is a function of comfort with risk. Being comfortable with risk doesn't mean you avoid a problem or deny it exists altogether—it just means that you can be comfortable finding another avenue that isn't your first choice or that puts you at greater risk.

The way to reach something that resembles equilibrium between caution and risk-taking is to apply it with another component of AMs—visualizing outcomes. By further playing that game of mental chess, you should be able to think through the risk factors of the operation. Every move you make comes with a risk, and some risks are the unintended consequences of simply executing an attack. If you try to think about every single measure of risk involved, step-by-step, you will walk straight into failure. But keeping your end goal in mind and thinking through how your next move may impact how you achieve that goal is a good start. It will keep you balanced and on track. Keep a holistic assessment of the risk running in your mind.

To sum up, when executing the attack, you should not be overly or overtly cautious. There has to be a sense of comfort with risk when executing. There is, however, lots of room for caution preceding the execution, which, as you'll see, your DAMs will take care of. The biggest issue of discomfort with risk when executing an attack is that it can reveal you as an intruder. OAMs allows you to maintain a relaxed approach and to act without showing hesitation and avoid the dangers of overthinking.

Planning Pressure and Mental Agility

One of your greatest advantages as an EA is that you know you are attacking, whereas the target is typically oblivious. Often this advantage translates to the illusion of control—the tendency for all of us to overestimate our ability to dominate and manage events. Strictly speaking, you do not have control over the outcome of any operation; it's down to randomness or “luck.” You can do things, however, to steer the outcome in your favor. The initial reveal here is that an abundance of caution will hamper this ability to steer, whereas a relaxed, but risk-aware, approach will function and perform far more highly. This may seem difficult given that, as an attacker, you need to maintain extremely strong offensive mental agility.

You should be focused, intense, aiming to win, and primed to take advantage of any opportunity for success that real-life attacks provide, also known as mental agility. Note that, even if you plan an attack within an inch of its life, you will still not be able to accurately account for the actions and reactions of your targets. Without mental agility, an attacker may be good, but they will never be great.

Planning in and of itself will not lead you to feel pressure, but insisting you stick to the plan will. It is also likely lead you to failure. You must be able to interact and react to the environment. No one wakes up and says to themselves, “Well, today is the day I will not react to my environment.”

Sometimes we get so set on winning that we get tunnel vision on the one route we want to take, not the one that's opening up in front of us. You must be able to adapt. When nothing is going as planned, you have to be able to pivot. When everything is going as planned, you should still recognize the opportunity to pivot, especially if it leads to a shortcut.

I've had to pivot more times than I've had hot dinners, and thankfully, not all have led to success. One of my first jobs saw me turn up at a small office as an IT consultant, which wasn't all that far from the truth. I was promptly introduced to the facilities manager, who was exceptionally nice to me. She gave me a cup of tea, and I told her about my love of British biscuits because I saw some in the kitchen, and I am not above hinting. Mere minutes later I had enough to eat and to take home. News of an IT consultant's arrival soon traveled, and not too long after I had staff coming up to me inquiring about some issues they were having on their computers—enter the pivot!

I, of course, agreed to take a look so that I could open a command prompt—allows you to run programs, manipulate Windows settings, and access files by typing in commands, the perfect low-key privilege escalation I'd been looking for. After a few minutes poking around pretending I knew what I was doing, I opened Terminal and took a discreet photo and thought I'd be on my merry way—except someone asked me a very simple question that any IT professional would know, and I crumbled like a two-day-old British biscuit. They saw me crumble, and minutes later the whole operation was on its knees because the manager of the office insisted on calling my cover company, which didn't exist. All because I couldn't recall what RAM stands for. (I can now at all times.) I still managed to pivot. When there was no answer on the other end of the line, mainly because it was ringing the burner phone in my pocket, I soon began to act indignant. I left papers to sign and told them where they could send them and got on my way.

This is the other advantage of OAMs: when you're under pressure, an offensive edge makes continuing the operation less challenging. Being able to pivot suddenly to continue trying to achieve the objective is a specialist skill. Mine let me down only when I got so flustered by an unexpected question that I couldn't recall the words random access memory. But it picked back up when I felt the heat rise and the possibility of arrest become a real threat.

Using OAMs to combat the pressures of planning and pivoting is, admittedly, easy to comprehend in theory but hard to practice. Learning this mental skill on the job is among the trickiest of things to do, but it's possible. There is definite value in seeking out stories from people who succeeded in pivoting and from those who have not.

Ultimately, using OAMs under pressure provides the ability to develop effective contingency plans, which is a critical mental skill for frequent decision-making, not only while in an active attack scenario but leading to that time as well. As an aside to this, for some people it will take time to learn this particular offensive strategy—working under pressure is on a spectrum, not a case of “you can” or “you can't,” so we can all do it to varying degrees. Finding ways to build up this skill is tantamount to success as an ethical attacker, because it's a constant when you're out in the field. It may be adding a little more stress to your current role; it may be building up physical challenges. The point is that you have to build up your tolerance from stress and become increasingly immune to its effect on your critical thinking. For some people, it will seem to come naturally. Many of the individuals I've come across that have found picking up this skill easy have had seemingly tough initial conditions or have had experiences that have made using skills like this one second nature. It is definitely something you can learn if you aren't quite a whiz under pressure yet. Breathing is your greatest tool, as nuts as that sounds. But checking in on your breathing in moments of stress isn't some hippie-dippie technique. It works. It helps you process what you are feeling, which is most likely what's prohibiting you from thinking clearly. Lean into it and let it pass. You will become better and better, faster and faster at it.

Emergency Conditioning

Another component of OAMs is the ability to visualize, create, and construct scenarios based on information, which should serve to keep things straight in your mind. There's a game of mental chess to be played before each attack, as I've mentioned frequently. However, you cannot assume that you will conjure up the exact scenarios you will walk into, because there's no conceivable way to picture every act, action, and reaction that may occur. This ability to visualize is not shorthand for “manifestation.” It's simply a good offensive warm-up strategy that can get the offensive juices flowing, so to speak. It's a skill you can build up now that will help your future self—and it makes thinking critically in the moment easier.

The brain is the strongest force in the body. It can overcome many adverse things, especially if you practice mental preparation. This practice can allow you to far exceed your physical and even mental limitations, but you have to train your brain for it. This sort of training relies on two things that you will need to do and use: first, be prepared to use the fourth law of AMs; make every move count in the direction of the objective.

Second, you must also be able to employ situational awareness, which is essentially knowing what is going on around you. That's a broad definition, but there are items that you should look at. Above all else, start with entry control and access. There are two ways you must pay attention to these things: you must know how you are entering and how you can exit. This is true of network pen tests when exfiltrating information and covering your tracks, to vishing tests where starting and ending the call naturally enough so as to not invoke a negative feeling from the target is often essential. You never want to raise suspicions. You must also try to gauge how porous the establishment is overall. Both may include looking at doors, gates, fences, walls, windows, skylights, even sewage pipes. Look for how easily vendors gain access, where they park, and so forth. You should look for wall and ceiling cameras and even body cameras. You should try to be aware of motion sensors and other barriers. In a sense, attacker mindset and attacking is part of the built environment; the design of any structure always implies a way to exploit it.

Just as architecture and crime intersect, so, too, does efficient crime intersect with cities and even neighborhoods. You should also consider both of these. For example, if you were to think like an attacker breaking into a bank in Los Angeles, you might consider how far you are from one of the Freeways, the main links connecting downtown and the suburbs, which spread throughout the region in a vast network of concrete ribbons. You would study where exactly you were headed after the heist and not time the operation for rush hour. As an ethical attacker you might not need to think of these things as you have tangible confirmation that you are there to test security, typically in the form of a letter from someone high up within the organization, but because a real attacker does not, they will think about the broader logistics. You might also consider that Los Angeles, a sprawling county composed of a series of widely dispersed settlements, is heavily policed from the air—more so than any other US city, and that getting away without law enforcement being informed is of the utmost importance to your get-away being a success. But Manhattan, NY, on the other hand, is not anything like this. Its long, skyscraper-lined streets make policing from the air more cumbersome. It would also be notable to an attacker that Manhattan is surrounded by water, making alternative methods of escape plausible. Not to mention the elaborate, comprehensive subway system—another area hard to police effectively. However, the streets of New York lend themselves to police cars chasing suspects pretty well, and the plethora of alleyways that result in dead ends can make escape hard should the authorities or security be alerted of your operation.

In a network pen test, gathering as much information as possible for the compromised environments and the domain network means having situational awareness. Pre-entry, reconnaissance on infrastructure can tell you quite a lot about the target's network, too. Tools like NsLookup (www.nslookup.io)—a command-line tool for querying the Domain Name System (DNS) to obtain a domain name or IP address, or other DNS records—and theHarvester (https://github.com/laramies/theHarvester)—used to gather information of emails, subdomains, hosts, employee names, open ports, and banners—can give you a lot of information to start building your attack and increasing your awareness of the target's environment.

Including situational awareness in assessing whether your next step is for the good of the objective or not is non-negotiable. You cannot blindly attempt to obtain the objective; you must use the information you know and the information around you, reevaluating the further you get into the target's territory. Of course, this is true for actual events, but if you are practicing emergency conditioning in your mind you will have to imagine variations of what is included when assessing your surroundings. Which leads me to this: when practicing emergency conditioning, the purpose is to not get fixated on any one move or outcome.

The best analogy I have for it is this: if you have to picture yourself crossing a busy road, envision getting hit by a vehicle…a fun task. You have no way to know the color, make, model, year, or speed of the car, you won't know if it has a dashboard camera attached, and you won't know the direction it will hit you from, but you can imagine being hit by it at all speeds, what you'd do depending on the speed, where you get hit, and so forth. And then you can try to imagine dodging that car from different angles depending on its angle of approach. You can imagine it all a hundred ways or more, and you should always imagine surviving.

By imagining it, you will think of the sounds a car driving at a high speed makes, the difference in volume as it skids around a corner, and so forth. By doing this over and over, slightly differently every time, you might be better prepared when the time to cross the road actually comes. You would likely be quicker to dodge a car, even if in our imaginings it was yellow, and in actuality, it was a truck. I know, that was very uplifting.

This type of mental exercise is akin to emergency conditioning, which is just a training technique used to make unknown situations seem familiar. You are basically tricking your brain into being familiar with an experience so that when it, or something similar, actually unfolds in the real world, it doesn't seem as intimidating or daunting and your reaction rate will go up.

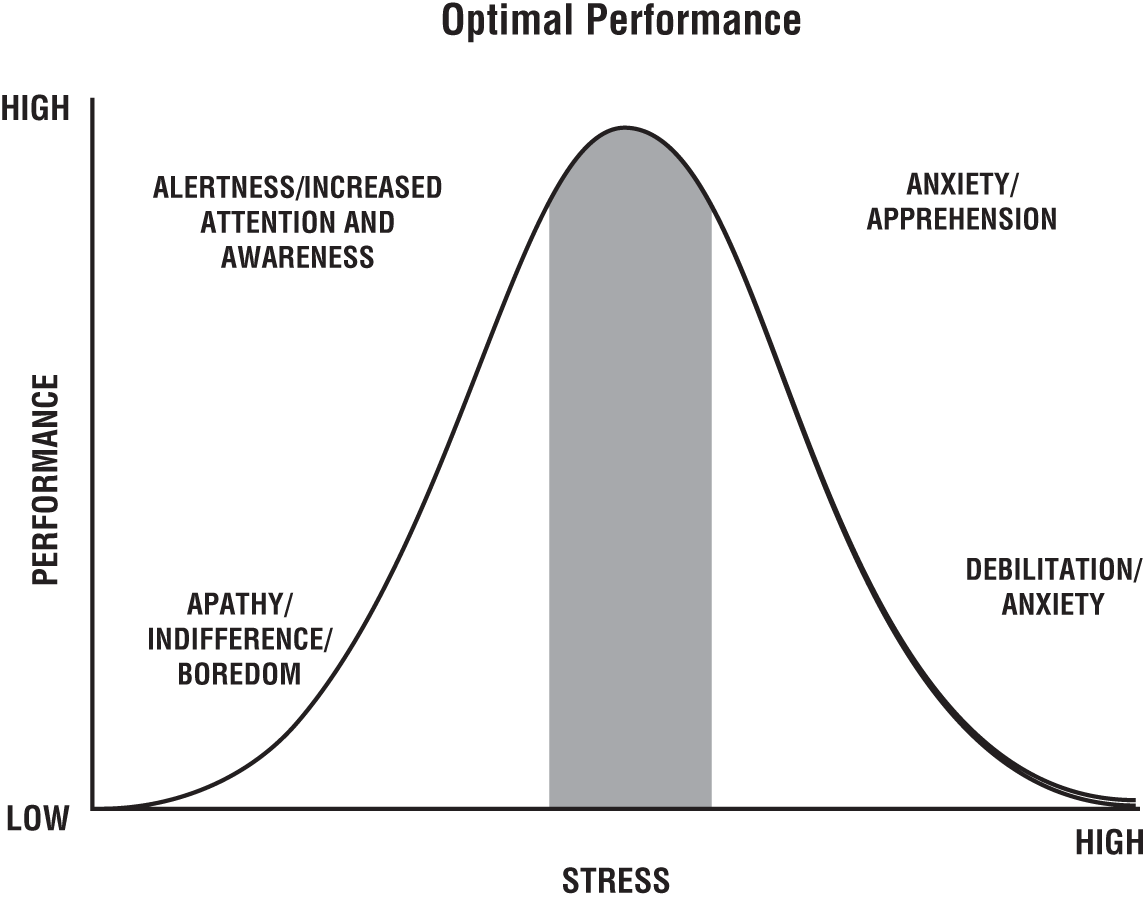

Notably, there is an upside to experiencing moderate levels of stress—even if you are just imagining the stress. Stress is often viewed as an absolute negative. It occurs when someone feels an imbalance between a challenge and the resources they have to deal with it. But it turns out that there are different kinds of stress and that, in smaller quantities, it can be very helpful. Eustress (beneficial stress) is a common form of stress. It's the sort of stress you feel before performing, and as EAs our job is to perform, in the sense of both execution and acting.

The factors that lead to eustress result in short-lived changes in hormone levels in the body. Normally, this type of stress does not last long and will not have long-term negative health effects. These smaller levels of stress can enhance our motivation. Small doses of stress can also force people to problem solve, ultimately building the skill and their own confidence in it. However, the relationship between the brain's health and stress is a very selective one, and there's no universal preferred amount of stress, because each of our brains is different. Most importantly, this effect is only seen when stress is intermittent. When stress continues for a prolonged period of time, there is a buildup of cortisol in the brain that can have long-term effects. Thus, chronic stress can lead to many health troubles. When chronic stress is experienced, our bodies produce more cortisol than it can release, and high levels of cortisol can wear down the brain's capacity to function properly. Several studies indicate that chronic stress impairs brain function by disrupting synapse regulation—resulting in the loss of sociability and the avoidance of interactions with others—by killing brain cells and even reducing the size of the brain. The prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain responsible for memory and learning, undergoes a shrinking effect when high levels of cortisol are present due to chronic stress. It can also increase the size of the amygdala, which can make the brain even more receptive to stress. A vicious cycle that has no upside.

The following graphic shows where optimal performance lies in conjunction with optimal stress and what can occur as a result. However, as noted previously, there's no universal preferred amount of stress. You will have to figure how much stress has the Goldilocks effect for you.

Finally, confidence in OAMs’ skills allows you as an attacker to stay on the offensive in live attacks, to be in a state of readiness. The bottom line of OAMs comes down to being able to analyze an organization, identify the security gaps and exploit them effectively, knowing the risks and acting anyway. You are the storm that forces change in critical infrastructure and environment.

Defensive Attacker Mindset

Defensive skills help attackers succeed consistently and in all conditions. Defensive skills include the capacity to adapt and respond to surges in security or target resistance. The key words that describe defensive mental skills are balance, resilience, and caution.

When your defensive skills are strong, you become a consistent performer, finding success in the smaller components as well as the overall attacks far more often. Whereas with OAMs the ability to apply change is a coveted skill, with DAMs the kernel of success is the ability to adapt to change. With DAMs, adapting with resiliency is critical.

Consistency and Regulation

There's another link between OAMs and DAMs we need to explore: offensive mental skills are necessary for excellence, but as attackers we need defensive skills to maintain excellence. OAMs’ penchant for stealth and competition—and the drive that comes with it—will be complemented by your defensive skills, allowing you as an attacker to be resilient and consistent in any conditions. This shows up when you pivot in a bid to win—your OAMs pushes this while your DAMs regulates it, making you consider the risks, even if fleetingly, and thus ensuring endurance. It also allows much of your agility to be executed carefully, because OAMs is primarily concerned with winning and will use persistence as a force, sometimes to the engagement's detriment. DAMs will take that power and cool it, keeping you stable.

Another way in which DAMs strikes a healthy balance with OAMs is in organization. Whereas OAMs demands that you pivot and apply new information for the good of the objective, DAMs allows for a standard to be adhered to. You must always apply information in an organized, efficient, and useful manner. You cannot blindly try things without surveying the environment for defenses that would thwart your plan.

Anxiety Control

One of the most important facets of DAMs is its capacity to help control anxiety. This becomes more critical, more vital, and even more indispensable as the critical stage of the attack approaches—this is recognizable as the point at which the significance of the operation typically increases. If you fail at that point, the operation is over. There is no room for error and no second chance.

At this point, there is less room for flexibility with options and opportunity typically becoming scarcer, too. I like to think of this as a funnel effect; the further you get into an attack and the closer you get to reaching your objective, the fewer options and less freedom you have. There may be only a few moves that would allow you to achieve your desired outcome. Anxiety-inducing stuff.

Here's an example: When approaching a building, you may have the choice of 10 entry and exit points to try. Once inside, you may have three or four routes to the security operations center (SOC), for example. Getting into the SOC may come down to two potential moves: up through the tiled roof and down the other side or through the door should you able to get it open. There's the bonus “option” of randomicity, which may show up as someone walking out of the SOC's security doors, allowing you to walk effortlessly in, but you typically wouldn't count on this. As the funnel effect unfolds, it's easy for anxiety to build.

When the body perceives a stress, it goes into “fight or flight” mode. Our attention gets highly focused and a slew of other bodily changes take place. This innate response is what allows parents to flip cars off their children and injured soldiers to continue fighting. Alas, there is a limit to how beneficial stress is. Too much stress causes performance to suffer. You may also take time to identify the root cause of your nervousness.

Clammy hands. Dry mouth. Shortness of breath. Shaky. Tense body parts. Sound familiar? Nerves. They get too many of us too often. As I've already confessed, I break out in a weird, patchy rash when I am really nervous. The old-age method of picturing your team or target in their underwear is by far the worst idea you'll have on the job, and thankfully you might not need to. Employing your DAMs means you should be able to quash, or at the very least quiet, those nerves before they've taken root. Identifying the root cause of your nerves will help you conceptualize them, which means that you can apply reason to them. This is important for multiple reasons, not the least of which is stamping out that anxiety and enjoying critical thought processes again. The first step is to interrupt that feedback loop.

Anxiety often begins in the amygdalae, which is where your brain processes memory and interprets emotions. It's now understood that you can reduce anxiety signals from your amygdalae if you assign names or labels to the emotions that you're experiencing at the time.

Another effective way to bring back critical thought processes is a breathing technique practiced by the Navy SEALs called tactical breathing. It focuses on slowing your rate of breathing down by pushing the breath through the nostrils, counting to four for each inhale and exhale. This technique might seem simple, but it has a huge impact.

Now, I'd like to note that your DAMs will have to work in concert with your OAMs at many times. For instance, if the root reason for nerves is fear of loss of control, you will have to employ functions from the OAMs “comfort with risk” structure. Sometimes all your DAMs can do is help you identify the origins, which is still a huge help that shouldn't be overlooked. In other cases, DAMs is enough; if the root cause of your nerves is that you feel you don't have enough information, you've underprepared. DAMs will help you ensure this never happens—if you employ it by ensuring you prepare and consider the defenses you will go up against.

Remember, the defensive side of the AMs is what helps a great attacker win consistently and in all conditions. Defensive skills include the capacity to adapt and respond. Through DAMs you know there are many uncontrolled variables, and it's easy to get overwhelmed. Simply knowing this is enough to begin turning the tide. DAMs can give you a high level of understanding and allows you to control anxiety, because defensively you know neither stress nor anxiety will aid your performance and that OAMs has you covered on the opposing side.

Instill in yourself the point of any defensive strategy—to fend off and block what doesn't serve you or that wants to harm you. Prepare and remember your goal, adapt to the situation, and respond with confidence in knowing the attack will never overtake you. You are performing it. DAMs is a regulator; it keeps you calm and allows for a modest amount of caution. Whereby OAMs allows you growth in stressful moments, DAMs regulates the stress you feel so that you actually use it as a driving force, recognizing it as a reason to adapt to, and then apply, your own changes.

Recovery, Distraction, and Maintenance

The skill of quickly recovering from setbacks is a defensive mental skill that pays dividends in lengthy engagements. This, coupled with the ability to focus despite distractions, is a potent combination completely in your favor as an attacker. This is critical at times where distractions increase in proportion to the size and importance of the job. It also helps prevent false positive opportunity identification. Not every incident or event is an opportunity for you as an attacker—sometimes it's just good enough to be able to observe them, with no need to act.

Finally, mental maintenance skills, or the ability to maintain simple, effective thoughts under pressure, is often the difference between having a great plan and executing a great plan. DAMs should amount to consistent performance and continued success on jobs.

OAMs and DAMs Come Together

There is overlap between the two sides no matter how you slice it. Having them categorized within our minds isn't important. Looking at the skills and building them up together is the real goal.

Offensive mental skills allow attackers to achieve what most ordinary people would find hard to believe, never mind actually perform. Defensive mental skills give attackers consistency and resiliency. The combination of both will result in a powerful attacker, able to test the most hardened of defenses and also able to provide solution-based feedback for clients left feeling shattered, most often because they could not have conceived of such an attack mere hours before it was performed. The performance of an attacker missing either of these skills will be diminished.

Summary

- OAMs: offensive attacker mindset

- DAMs: defensive attacker mindset

- The offensive attacker mindset allows you to direct an event in the direction of the objective and be comfortable with the risk of doing so.

- A defensive attacker mindset will help an attacker win consistently and in all conditions.

- DAMs also teaches you that getting to the root cause of an anxious feeling will help take it from a feeling to a thought that can be broken down and dealt with and, hopefully, eradicated.

- Whereas your OAMs wants you to pivot at every possible opportunity that presents itself, your DAMs holds you back when necessary, knowing that not every incident or event is an opportunity and that observation without action can be just as powerful.

- Whenever the two are in conflict, OAMs will push you to do what it takes to win; DAMs will pull you to use caution, urging you to not take big risks.

- If there's no life-threatening danger, and you are closing in on the end of an attack, you should go for the win. If the risk you need to take in that moment threatens the rest of the engagement, fall back and reassess.

Key Message

Being able to think straight and maintain effective thoughts under pressure is key when working in a hectic or fluid situation. Preparation and staying aligned with your goal and adapting to the situation are critical. Your mental agility is a great asset, as is believing the attack will never overtake you. You are performing it. You have as much control as you will ever have. The rest is chance. Find comfort in that.