6 Street Photography

Good photography does not always have to capture special moments; it can also devote itself to the seemingly trivial and commonplace.

Photographing people on the street is a challenge. How do you skillfully integrate strangers into a pictorial composition and still manage to maintain discretion?

So-called street photography has a long tradition. As early as the late nineteenth century, photographers started turning their attention from the ivory towers of static, staged, and idealized artistic photography to life on the streets. This direction often mirrored social reform. The camera served as an objective analytical instrument for documenting the dark side of early industrial modernism with its dramatic upheavals. The social fabric of large cities, in particular, underwent dramatic changes. Lewis W. Hine, for example, documented child labor in the United States as early as 1907, and his work was instrumental in the adoption of laws that outlawed the practice. Hine’s image of a young boy selling newspapers on the street became famous.

However, the high point of street photography started in the 1920s, bolstered by the introduction of the Leica camera. Photographers let themselves be carried away by the flux of the metropolis with its paradoxical, ambiguous universe, and they photographed freely from the hand. Aesthetics changed: What was accidental, casual, surprising, fleeting, and also trivial in urban events became the subjects of these photographers. The camera served as an extension of their subjective view. The metropolitan stroller with the camera was born: The fleetingness of seemingly trivial moments of social phenomena became important to photograph, and of less interest were specific events. The line between street photography and social documentary photography became blurred, as can be seen in the photos taken for the Farm Security Administration (FSA) Project by Edward Weston and Dorothea Lange, for example. Though often impressive, social documentation emerged from it—especially when seen retrospectively—and street photography also snatched moments from the flow of events and identified the photographer as creator of his own reality. Everything seemed to be worth photographing. Henri Cartier-Bresson’s decisive moments are still spectacular today, and his photographs reveal moments of very special importance. In the 1960s and 1970s Gary Wino-grand and Lee Friedlander completely devoted themselves to the banality of everyday life, be it a dog that sits on a deserted street that has remarkably boring architecture or a man wearing a hat walking by a McDonald’s restaurant (something Edward Hopper could have painted). Street photography, despite all the apparent triviality of its subjects, is no less than an encyclopedia of the times.

The seemingly meaningless (yet meaningful) simplicity of everyday life can be captured in a photograph. How do you approach street scenes and give importance to the seemingly meaningless in a photograph?

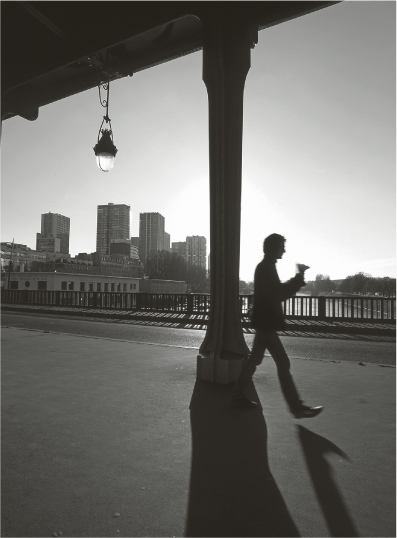

A Foot before Setting It Down

The photo in figure 6–1 shows a banal scene: A man with an ice cream cone in his hand walking by nondescript skyscrapers. And yet, there is a certain magical feeling to the scene. This magic is due to several factors: The backlight gives the image its mood. The bridge over the Seine with its pillar creates an interesting graphic structure; the lamp is an anachronism that lends a bit of nostalgia; and the person is just putting his foot down, while his leg’s shadow shows below. This banal moment has been captured and enhanced to become something special through the proper use of light, composition, and design.

If you see a person walking from faraway, as is the case here, and you know in which direction they are headed, it is best not to set the camera in position. People often change their course and walk behind the photographer because they want to be courteous and not block the photographer’s view. To prevent their change of course, aim the camera in another direction at first and then change it to the desired position at the very last moment. However, it certainly helps to plan the composition beforehand. In this photo, the pillar divides the image into the vertical golden ratio. Pictorial tension has been created between the man walking out of the picture at right and the left part with its skyscrapers and street lamp.

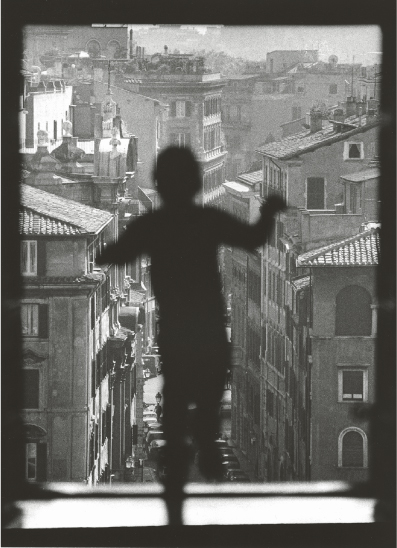

Jumping Child

The moment captured in the photo in figure 6–2 also seems banal. The photo is about nothing more than a child starting to run down a flight of steps in Rome. And yet the image goes beyond this common life moment. The viewer sees the scene as if the child will jump into unknown depths because the camera hides the steps and shows only the projecting part and a leap into the street. The child’s silhouette fills the image and the photographer has captured the moment of jumping. The child’s right leg is swinging forward, and the child’s raised right arm stresses the dynamism of movement; a leap into unknown depths is perfectly suggested here.

How is such a street photo created? The photographer invests enough time planning it, of course. The photographer had to carefully set the composition in advance. The 105 mm telephoto lens takes care of a tight perspective. Because a short exposure time (1/500 sec) had to be chosen, there was hardly any depth of field, and the plane of focus naturally had to be set on the detailed background. With these settings, the subject would then be slightly unfocused to the viewer. The photographer had to wait about 10 minutes and make sure to shoot at just the right millisecond so the jump into the unknown depths could be suggested. The minimal but nevertheless crucial shutter lag intrinsic to the construction of early digital cameras would have made this photo impossible.

The People in Front of the Government Building

The scene in figure 6–3 takes place directly in front of the Parliament Building in Berlin’s government sector. A man with a braid, who can certainly be described as a typically eccentric Berliner, gesticulates in front of two young men. It is truly street photography to capture such a moment. Backlighting is especially suitable for black and white photography because it can show architecture and people in a highly graphic way. If the government building presented a bombastic, almost sterile impression, the brief human gathering infuses some life into the scene. In fact, man and architecture really do not go together in this photo. Although the three persons have been reduced almost to silhouettes, the impression is that they would normally feel more at home in other premises. This makes us contemplate the quality of modern architecture: Surely such a government building expresses power and coldness; does it overpower people and make them feel like strangers in their surroundings? These three persons, however, assert themselves against the architectural coldness through their intense discussion. The photo was taken digitally at a focal length of 70 mm.

Mysterious Couple

Although nothing special appears to be happening in the image in figure 6–4, backlighting and the finely textured, fleecy clouds of the sky give it a special atmosphere. A nicely decorated railing also gives it a special, romantic mood. A somewhat strange couple is seen coming down the stairs. Although only the couple’s silhouette is seen, you can clearly recognize a rather young man who is taking a considerably older and stooped woman by the hand. Are they mother and son? Or is it a real couple such as the one seen many years ago in the famous movie Harold and Maude? There is a certain melancholic element to the image; youth and old age give each other a hand. The image suggests that they are inseparable companions.

The composition is strong because it leads the viewer’s eyes through the image from left to right and down the steps with the couple but stops at the man who turns to the stairs, thus keeping the focus in the picture. If you reverse the composition, it loses this effect because you see the couple first and then the stairs; the impression that the couple has just come down the flight of steps is lost (figure 6–5).

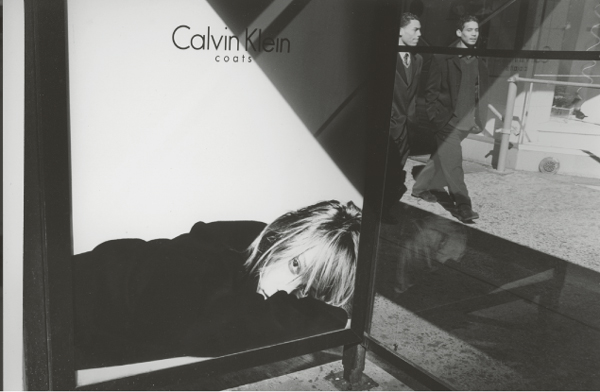

Calvin Klein

The image in figure 6–6 shows a seemingly inconsequential scene in New York, typical of street photography: Two men walk by a bus stop that has a Calvin Klein ad posted. Photography often can relate things to one another even though they have nothing to do with each other or—as is the case here—they are related to each other unknowingly for a fleeting moment. This ability is, however, precisely the magic of photography. It can capture two men so perfectly in an image (as happens here) that you cannot help but associate them with the reclining beauty in the Calvin Klein poster. The men seen here could be part of the advertisement: They are roughly the same age as the woman in the poster and wear suits that could be from the Calvin Klein brand. Their walk is dynamic, whereas the reclining woman lazily looks at the passers-by. The woman poses as a passive person. Naturally, she also exudes eroticism; because she is reclining and looking directly at the viewer, a subliminal invitation is suggested. Both men should feel the invitation of her eyes, but they ignore it and hurry onward.

Advertising and reality influence each other: Good advertising recognizes and strengthens the latest trends, or conversely, it sets trends that influence people.

The image is composed of triangles. Both men move toward the bright triangle and the dark triangle is subdivided into two smaller triangles by the metallic column of the bus stop. Although both men are headed out of the picture, the diagonal line of the bright triangle leads the viewer’s eye back into it.

The photo was taken using a 28 mm wide-angle lens.

Hitchcock Atmosphere

The photo on the previous page (figure 6–7) is also a banal, everyday scene; once again it is the special atmosphere that makes the picture interesting. The railings of the subway shafts in Paris create the so-called negative diagonal from the upper-left to the lower-right corner. The eye, which “reads” a picture from left to right, is led out of this photo, but the shadows of both persons return the viewer’s attention to the center of the photo. All the figures turn away from each other; even the figure of the lower shadow turns away from the upper figure. The dominant diagonal middle shadow gives the photo a feeling of heaviness, and the concrete adds an eerie, almost sinister quality.

Street photography preserves the moments that occur right next door and on the street; it makes a statement about everyday life and the feeling of being alive.