7 What Does Landscape Photography Mean in the 21st Century?

On hearing the words landscape photography, you probably think of Ansel Adams, who is one of the world’s most famous photographers. He put his stamp on landscape photography like no other photographer has, traveled throughout the most beautiful places in the United States, and used all the technical means at his disposal to make landscapes appear heroic. Using the zone system, he divided the earth into 10 different black, white, and gray tones—each one aperture apart. In every photo, he used the zones to determine what area of the gray value curve of his negative he should expose. Just as important for creating his pictorial moods were his correct use of filters and his perfect darkroom technique. His photo Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico is one of the world’s most celebrated photographs. What makes his images exceptional are not only their special atmosphere and their exact tonal values, but also the large format that shows every needle of a fir tree. Ansel Adams took photography of unspoiled nature to the highest reaches.

What innovations can landscape photographers make to surpass Adams? Is it really possible to show unspoiled, idyllic landscapes in our modern world? Surely, the answer depends on what you demand from photography. The serious amateur or semi-professional will make high demands; the representation of unspoiled, idyllic scenes in today’s world will probably not be satisfactory. After all, you cannot achieve the quality of Ansel Adams’s photographs with a small-format camera, be it analog or digital.

In contemporary photography, there are almost no important photographers who take idyllic scenes. Thomas Florscheutz may be one of the few exceptions, but he does not show landscapes. Instead, he shows extremely abstract yet aesthetically pleasing botanical photographs. Otherwise, unspoiled landscapes are extremely rare or they are abstract in contemporary photography, such as in the following examples:

• Michael Kenna shows landscape moods in his atmospheric black and white photos (in his book Night Work, for example) that consist partly of sea, sky, and a minimal foreground of a couple elements. However, the power of the few subjects in his images is unfolded due to special lighting.

• The Japanese photographer Sugimoto has reduced his seascapes even more. Sugimoto’s images show only two surfaces: The sky and the sea in black and white are placed exactly in the middle (in defiance of classical composition rules), so viewers see only two areas of equal size with two different, almost monochromatic gray tones.

• Michael Wesely reduces and abstracts his work in another way: This contemporary photographer—whose photos sell briskly worldwide—positions the camera horizontally during exposure, so his photos are reduced to nothing more than washed-out stripes. When the photos are seen from a distance, they resemble the scanner bar codes in supermarkets.

However, another approach started developing in the 1950s: showing breaks. In modern industrialized countries, you can hardly photograph an unspoiled landscape without being exposed to the criticism of showing a “lie” or “making it all prettier.” In painting, the realism movement of the last century—as opposed to naturalism—not only represents a pure world, but depicts social conflicts as well. Playwright Bertolt Brecht wrote a great deal about the realism movement, and this movement can in fact be applied to photography. Realism represents the essential character of the environment instead of its superficial appearance. One of the best-known contemporary photographers is Leipzig’s Hans Christian Schink. He shows the merciless attacks of the modern world against the landscape (for example, the way newly built highways or railway bridges intrude into the East German landscape). In his large-format photos, you can clearly see how concrete almost violently destroys the fragility and harmony of nature.

Photographer Heinrich Riebesehl of Lower Saxony focuses on images of pure boredom. In his well-known Agrarian Landscapes he purposely takes unexciting photos of the boring cultivated fields of his state under gray skies.

One of the few Magnum photographers with an interest in landscape is the Czech Josef Koudelka. His panoramic landscapes, however, reflect no unspoiled world but instead show abandoned tracks of human intervention in a landscape so barren that you could imagine he captured his images in a post-nuclear catastrophe.

It would be a pictorial lie to offer only the images of an unspoiled contemporary world in contemporary photography. To show only unspoiled nature, you should not show the clichéd image of an idyllic world, but abstract the image or create something mystical so the image goes way beyond the idyllic; a couple of examples of this are presented in the following sections.

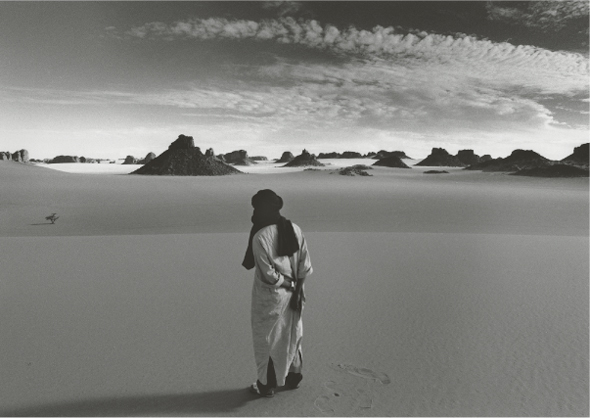

Unspoiled Landscape with Tuareg

The photograph in figure 7–1 approaches a cliché, yet it may be legitimate because it shows one of the last unspoiled landscapes of this world, the Sahara. Thus, all pictorial means have been used to suggest the openness and wildness of this landscape. The covered Tuareg has turned his back to the viewer and has therefore become a figure we can identify with; his thoughts become ours as both of us take in the seemingly endless panorama of rocks, sand, and sky. This image suggests the full unity and harmony of humanity and nature. And, it is not a lie because the Tuareg are in harmony with their environment in ways that are absent in Western industrial societies. A small break from nature in this photo is the large wristwatch worn by the man. The wristwatch indicates his contact with Western civilization. Naturally, it is legitimate to take such photos in the twenty-first century to record a piece of unspoiled world.

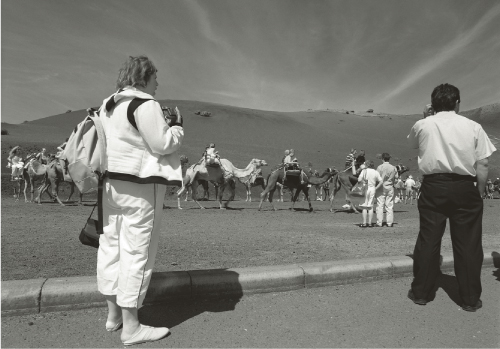

Persons and Landscape on Lanzarote

Unfortunately, the relationship of man and nature nowadays resembles the photo in figure 7–2, which was taken in the Timanfaya National Park on Canary Island Lanzarote: A woman wearing white sports clothes and floppy shoes carries a backpack, handbag, and video camera. She looks a bit lost and distracted. A man stands beside her and talks on a cell phone. In the center of this image, you can see a row of camels on which tourists sit somewhat clumsily. The scene takes place before a monotonous volcanic landscape. In this case, humans and landscape appear disconnected and alien to one another. Humans experience nature as part of a short camel ride in the mass convoy, a totally different approach to nature than that of the Tuareg’s in the previous photo. Here, nature is presented on a platter, as is the case in America’s national parks: Visitors drive by in a car, stop occasionally, look beyond the barricades, and exclaim, “Oh, great!” With that approach, you cannot possibly experience the actual force and wildness of nature because there is no need to work hard in order to come close to it. Humans and nature thus remain strangers, as is the case in this critical “landscape photo” that characterizes the museum-like human approach to nature in today’s world.

The photo was taken with a 20 mm wide-angle lens.

Abstractions in the Sahara

If the unspoiled beauty of a landscape must be shown, you should avoid the conventional shots. A way out of this trap is to create an abstract composition of the landscape with the camera—make a landscape’s abstract structure the subject of the image (figure 7–3). Saharan dunes and their interplay of light and shadow are tailor-made for this. Long focal lengths allow for better abstractions because they show only a cropped image of reality. In this photo, the interplay of two similar curves make it look as if they were painted with an ink brush. Another important pictorial element is the curve of the small dune in the upper-left corner; without it there would be no element of tension in the image.

The photo was taken with a tripod using a 300 mm focal length at aperture 22 to have the necessary depth of field in the sinuous dunes.

Creating a Mystical Impression

These two images also go beyond the conventional and move into the realm of mysterious, almost sacred imagery—a topic that is discussed in chapter 15, “Mystical Photography.” Clouds can often be used to increase the effectiveness and reduce the clichéd feel of landscape images. The island of La Palma, with its precipitous landscapes, is the scene of fascinating cloudscapes that often take shape before your very eyes. The photo in figure 7–4 encompasses an extremely broad range of brightness, and I had to take care to ensure that the reflections from the ocean didn’t burn out. I used a graduated filter that darkened the upper-right portion of the sky to a degree that allowed me to provide even the sun with good definition. I used the Photoshop Polygonal Lasso to select and brighten various parts of the lower half of the image while darkening the clouds in the right-hand portion of the frame. This meticulous postprocessing allowed me to create the unique mood that the image displays.

The second image (figure 7–5) also benefits from its own special lighting mood. It was taken from a boat near Dalyan in Turkey. The sun had already disappeared from view, giving the mountain and its reflection a mysterious, silhouette-like appearance. The waves caused by the boat’s movement introduce a dynamic element into the otherwise calm scene. This image too portrays an intact, idyllic landscape, but it’s nevertheless dominated by the mood of the lighting, which prevents it from appearing simply soft or insipid.

Death of Nature

The low mountain landscape seen in Germany’s Harz region, for example, looks rather conventional in photos (figure 7–6). It is rather difficult to make an interesting photograph of this pretty landscape, which is ideal for hiking and enjoyment. Yet, the German forests are in peril: Only 40 percent of German forests are healthy. The message in this photo is the death of the forest. I used all pictorial means at my disposal to show the death of trees in an impressive way. The twilight atmosphere requires a long exposure that would have been boring without the use of a flash because the entire foreground would have become pitch-black and the trees would have been perceived only as silhouettes. It was therefore important to combine the long exposure with a short flash. The flash could not be used frontally as I did not want to illuminate the trees in the foreground because the mood would have been lost. Therefore, the flash had to be used from the side, behind the first row of trees to give a part of the dead trees a three-dimensional look. Thus, the mood evoked by the light was perfect; the rising half-moon gives the scene its final touch. Differing from a conventional Harz landscape, the photo now has an allegorical scene that poses questions of how man deals with nature, and its atmosphere points to something mystical. The photo was taken with a 28 mm lens.