28 The Play of Forms—Conscious Repetition of Pictorial Shapes

During the course of this book, you have seen that there are parallels between pictorial and musical languages. Pictures can have the same rhythm as musical pieces; images can be composed in such a way that they have a leitmotif (i. e., recurring theme) that is repeated in a modified way. Many classical musical pieces have a basic leitmotif that is repeated throughout the composition, albeit in slightly varied forms.

You have already seen that most of the time, a photo is successful when its basic pictorial structure—from the purely abstract viewpoint when it is fully separated from the subject of the image—is also interesting to look at.

The first step should be to recognize and analyze these pictorial patterns in photos that have already been taken. The second step should be to identify the abstract patterns that underlie reality when you’re actively taking photos; in other words, to think abstractly and pictorially when looking at the real world. This is especially hard when you are trying to shoot content-related subjects whose composition is already demanding full attention. Even more difficult is to apply this kind of pictorial approach in street photography, for example, in the hustle and bustle of an urban setting, where everything is in flux and the abstract pattern of an image is constantly changing. If you also use a wide-angle lens, it becomes especially challenging to keep all edges of the picture simultaneously in sight while making sure to control form as well as content. Of all photographers, Cartier-Bresson was probably the one who mastered this challenge the best, because his news photos have not only interesting content, but also outstanding abstract patterns.

To approach the many varied abstract forms with the camera, it is easiest to identify only two similar patterns in totally different objects that will later develop a certain relationship in the image. This kind of practice trains the eye to find abstract shapes in objects and is suitable for creating exciting images out of rather banal landscapes or objects, as the following three examples will show.

What makes photography so exciting is that it brings together and blends two spaces that, in reality, are far away from each other and are often unrelated on the two-dimensional print. Thus, with regard to content, elements may be formally linked that actually have little or nothing to do with each other.

View from Schauinsland Mountain

The mountainous region of Germany, although refreshing and pretty, is difficult to shoot in real life because it frequently ends up looking very conventional in photographs. After all, the identical spruce plantations seen in the Harz and Black Forests do not look particularly photogenic. Another problem is that the three-dimensional view inspires enthusiasm, but this depth is almost impossible to capture on a flat surface. And yet, this two-dimensional pictorial space begs to be composed. In this case (figure 28–1), the landscape by itself would not have been enough for creating an interesting photo, but the two projecting corners of the observation tower do provide the much-needed pictorial tension. The corners are just as angular as the upper lines formed by the mountain crest. Similar lines having a similar angle are therefore repeated. The railing breaks up the quiet harmony of the landscape, and the soft shapes of the clouds contrast greatly with the pointed forms of the foreground. The photo was taken using a 24 mm wide-angle lens.

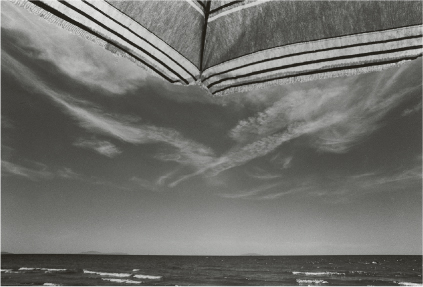

Umbrella and Sky

The photo in figure 28–2 taken on the tranquil Mediterranean, would have looked too calm by itself, so it was essential to include an element that would slightly disturb the calmness. The cropped umbrella was the ideal candidate for inclusion because its triangular shape resembles the triangle formed by the clouds in the sky. Both fleecy clouds give the image the symmetry it needs and lead your eye to the center of the image, which looks a bit surreal. The upper end of the umbrella looks quite abstract at first and is only recognized as such after a second glance, triggering the idea of unbroken nature. What is going on behind us? Is the area teeming with tourists? All this is left to the imagination of the viewer. The photo was taken with an analog camera using a 20 mm wide-angle lens. I used an orange filter to increase the contrast between sky and clouds.

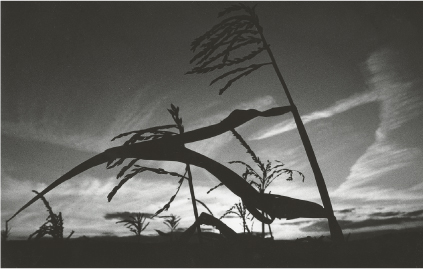

Reflection in the Sky

At first glance, a cornfield does not usually trigger the impulse to photograph it. However, the single plant backlit by the sky, and the two abstract shapes that resemble each other, can create a rather exciting photo (figure 28–3). The form of the plant is reflected in the sky, albeit mirror inverted. The photo uses the plant’s leaf as the axis of symmetry, and both leaves are reflected in the sky. The composition is very dynamic, last but not least, due to the rising slant and the leaf’s sweep that extends into the sky.

The image owes its dynamic quality to the view provided by a 24 mm wide-angle lens. The contrast was intensified by the use of an orange filter placed before the analog camera and a slight burning in of the sky in the darkroom. This photo proves that an ordinary scene found just around the corner in this boring field can lead to unusual ways of seeing.

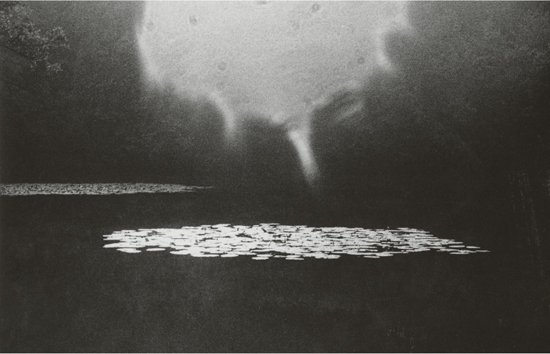

Water Lilies without Cliché

Clichéd photos of water lilies are very often used for illustrating rather shallow texts. Thus, the challenge here was to photograph these plants so the photo would not look clichéd. (Sunsets and sunrises present a similarly difficult challenge: pretty to look at, but most of the time degraded to a cliché on print.) When taking plant photos, however, backlight can come to the rescue, as was the case in the photo in figure 28–4. However, for this photo it was not enough because without the sun’s reflection, the image would have looked boring.

The photo was minimally composed. The composition comes from three pictorial shapes that vary slightly from each other: a larger oval formed by the water lilies in the center, a smaller one to the far left, and the semicircular sun reflection. Without this reflection, the photo would have been boring; it is the decisive final touch that gives the image a mysterious, almost mystical effect—and it changes the shape of the oval into a semicircle. Furthermore, four jagged edges have been “built-in” to the sun’s reflection, and the longest one points toward the middle oval formed by the water lilies. The backlight makes the pond’s surroundings and the trees appear dark and barely recognizable; only a branch is clearly recognizable in the upper-left corner. The photo works due to the extreme contrast of the water lilies, the sun’s reflection, and the dark background.

The photo was taken with an analog camera at an 80 mm focal length.