Figure 1-1: What Was . . . What Is

An ancient Western Red Cedar tree, thirteen feet in diameter, in the rainforest of Washington’s North Cascade Mountains, cut down a century ago, has been replaced by dozens of tall, skinny trees, which together contain less wood (board feet) than the single cedar contained. None of the new trees are Western Red Cedars. There are no ferns, shrubs, or mosses on the ground, so the replaced forest can support no wildlife. Timber companies say, “there are more trees in America than ever before,” and they’re right; yet it is an utterly deceptive claim. It’s a dead forest; a tree farm. The photograph, near my home, was designed to show the damage of industrial clearcutting, euphemistically called “harvesting.” No other art form can make such a statement as powerfully as photography.

CHAPTER 1

Communication Through Photography

![]()

PHOTOGRAPHY IS A FORM OF NONVERBAL COMMUNICATION. At its best, a photograph conveys a thought from one person, the photographer, to another, the viewer. In this respect, photography is similar to other forms of artistic, nonverbal communication such as painting, sculpture, and music. A Beethoven symphony says something to its listeners; a Rembrandt painting speaks to its viewers; a Michelangelo statue communicates with its admirers. Beethoven, Rembrandt, and Michelangelo are no longer available to explain the meaning behind their works, but their presence is unnecessary. Communication is achieved without them.

Photography can be equally communicative. To me, the word photograph has a far deeper meaning than it has in everyday usage. A true photograph possesses a universal quality that transcends immediate involvement with the subject or events of the photograph. I can look at portraits by Arnold Newman or Diane Arbus and feel as if I know the people photographed, even though I never met them. I can see landscapes by Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, or Paul Caponigro and feel the awesomeness of the mountain wall, the delicacy of the tiny flowers, or the mystery of the foggy forest, though I never stood where the tripods were placed. I can see a street photograph by Henri Cartier-Bresson and feel the elation of his “decisive moment,” captured forever, though I was not beside him when it occurred. I can even see a tree by Jerry Uelsmann floating in space and feel the surrealistic tingle that surrounds the image. I can do this because the artist has successfully conveyed a message to me. The photograph says it all. Nothing else is needed.

![]() Photography is a form of nonverbal communication.

Photography is a form of nonverbal communication.

A meaningful photograph—a successful photograph—does one of several things. It allows, or forces, the viewer to see something that he has looked at many times without really seeing; it shows him something he has never previously encountered; or, it raises questions—perhaps ambiguous or unanswerable—that create mysteries, doubts, or uncertainties. In other words, it expands our vision and our thoughts. It extends our horizons. It evokes awe, wonder, amusement, compassion, horror, or any of a thousand responses. It sheds new light on our world, raises questions about our world, or creates its own world.

Beyond that, the inherent “realism” of a photograph—the very aspect that attracts millions of people to taking “selfies” and other everyday digital snapshooting, or much of 35mm traditional film shooting—bestows a pertinence to photography that makes it stand apart from all other art forms. Let’s briefly review a few examples. At the turn of the 20th century, Lewis Hine bridged the gap between social justice and artistic photography with his studies of children in factories, and the work led directly to the enactment of humane child labor laws. In the 1930s and 1940s, Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, and a host of others raised public consciousness of the environment through their landscape photographs. Into the mid- and late 20th century a number of national parks, state parks, and designated wilderness areas were created based largely on the power of the photography. During the Depression years, Margaret Bourke-White, Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, and others used their artistry to bring the Dust Bowl conditions home to the American public. Today, photographs comparing the size of shrinking glaciers with photographs of the same location a century or more ago have alerted those who can comprehend facts about the reality of global warming and its deep problems. (Unfortunately there is too much pushback against obvious facts for much progress to be made.) But the bottom line is this: used well, photography can be the most pertinent of all art forms (figure 1-1). For the intent and purpose of this book, let us concern ourselves with photography as a powerful art form and documentary form, not for its fun-filled everyday uses as personal remembrances.

To create a meaningful statement—a pertinent photograph—the photographer must gain an insight into the world (real or created) that goes far beyond the casual “once-over” given to items or events of lesser personal importance. The photographer must grow to deeply understand the world, its broad overall sweep and its subtle nuances. This intimate knowledge produces the insight required to photograph a subject at the most effective moment and in the most discerning manner, conveying the essence of its strength or the depth of its innermost meaning. This applies to all fields of photography.

How does a photographer proceed to create this meaningful statement and communicate emotion to others through photography? This is a complex question that has no clear answers, yet it is the critical question that every photographer of serious intent must ask and attempt to answer at each stage of his or her career.

I believe the answer to that question revolves around both personal and practical considerations. On the personal, internal side are two questions:

- What are your interests?

- How do you respond to your interests?

The first question asks what is important to you. It’s unlikely, maybe impossible, to do good photography with subject matter that don’t interest you. The second question points you in the direction of how you want to express yourself, and even how you want others to respond to your imagery. Or, stated differently, how do you want your photograph to look, so that others will get the message you want to convey? To create the photograph you want to make, you’ll have to consider such issues as design and composition, exposure, lighting, camera equipment, darkroom or digital techniques, presentation of the final photograph, and other related considerations that turn the concept into a reality.

Let’s start with the first of the two personal, internal questions: What are your interests? Only you can answer that question. But it is critically important to do so, for if you are to engage in meaningful photography you must concentrate your serious efforts on those areas of greatest interest to you. Not only that, but you must also concentrate on areas where you have strong personal opinions.

Allow me to explain my meaning by analogy. Did you ever try to say something worthwhile (in ordinary conversation) about any subject you found uninteresting, or about which you had no opinions? It’s impossible! You have nothing to say because you have little interest in it. In general, that doesn’t stop most people from talking. Just as people talk about things of no real interest to them, they also take pictures of things that have no real interest to them, and the results are uniformly boring.

But let’s go further with this analogy. Take any great orator—say, Winston Churchill or Martin Luther King, Jr.—and ask them to give an impassioned speech on quilting, for example. They couldn’t do it! They’d have nothing to say. It isn’t their topic, their passion. They need to be on their topic to display their greatest oratorical and persuasive skills. The great photographers know what interests them and what bores them. They also recognize their strengths and their weaknesses. They stick to their interests and their strengths. They may experiment regularly in other areas to enlarge their interest range and improve their weaknesses—and you should, too—but they do not confuse experimentation with incisive expression.

Weston did not photograph transient, split-second events; Newman did not photograph landscapes. Uelsmann does not photograph unfortunate members of our society; Arbus did not print multiple images for surrealistic effect. Each one concentrated on his or her areas of greatest interest and ability. It is possible that any one of them could do some fine work in another field, but it would probably not be as consistent or as powerful. They, and the other great photographers, have wisely worked within the limits of their greatest strengths.

Enthusiasm

The first thing to look for in determining your interests is enthusiasm. I cannot overemphasize the importance of enthusiasm. I once heard that three human ingredients, when combined, will produce success in any field of endeavor: talent, hard work, and enthusiasm, and that a person can be successful with only two of those attributes as long as one of the two is enthusiasm. I agree. Photographically, for me, enthusiasm manifests itself as an immediate emotional response to a scene. Essentially, if the scene excites me visually, I will photograph it (or at least, I will take a hard second look to see if it is worth photographing). It is purely subjective. This positive emotional response is extremely important to me. Without it, I have no spontaneity and my photographs are labored efforts. With it, photography becomes pure joy.

Enthusiasm also manifests itself as a desire to continue working even when you’re tired. Your enthusiasm, your excitement, often overcomes your fatigue, allowing you to continue on effectively as fatigue melts away. On backpacking trips, I’ve often continued to photograph long after the others settled down at the end of the day simply because I was so stimulated by my surroundings. Once in 1976 on a Sierra Club trip, we finally arrived at our campsite after a long, difficult hike. Everyone was exhausted. But while dinner was cooking, I climbed a nearby ridge to see Mt. Clarence King (elevation 12,950 feet) in the late evening light. It was like a fugue of granite (figure 1-2). I called to the group below to come see this stunning mountain, but even without backpacks or camera equipment, none did. I was the only one to see that sight!

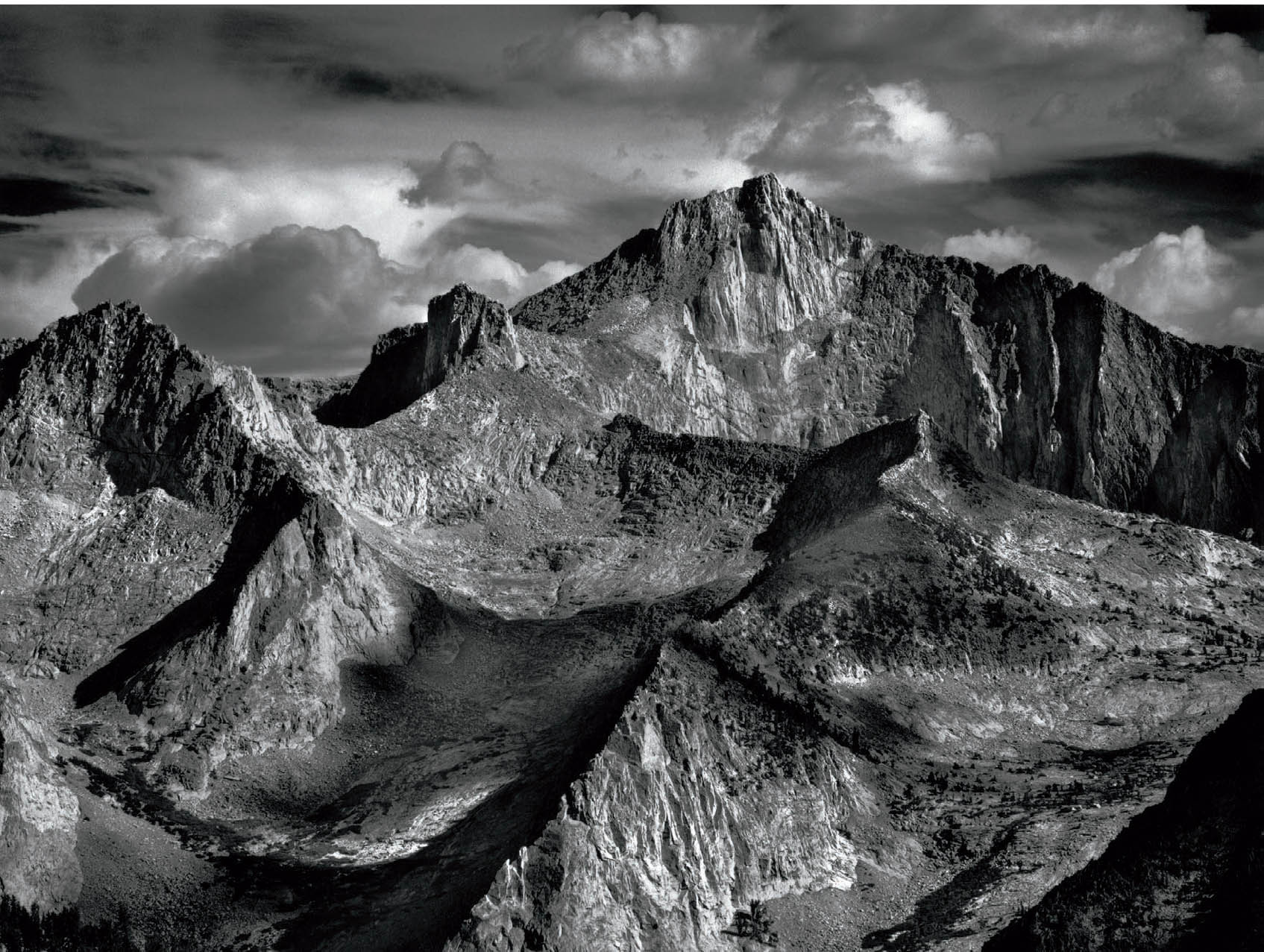

Figure 1-2: Mt. Clarence King

This grand crescendo of granite rises lyrically as evening light brings out each ridge, each buttress. I used a red filter to cut through any haze (though no haze was apparent) and to enhance the clouds by darkening the blue sky.

Likewise, I’ve worked in the darkroom until 3, 4, or 5 a.m. on new imagery because the next negative looked like it had great possibilities and I wanted to see if I could get a great print. More recently, I’ve spent equally long hours at the computer working to transform RAW digital images to final TIFF files, effectively oblivious to the fact that I was at the keyboard and monitor for hours after the midnight gong. In essence, I just couldn’t wait until tomorrow to work on new images. These are not things you do for money, but for love.

In the field, if I don’t feel an immediate response to a scene, I look for something else. I never force myself to shoot just for the sake of shooting or to break an impasse. Some photographers advocate shooting something, anything, just to get you moving under those circumstances. That’s pure nonsense. Why waste time on useless junk when you know in advance that it’s useless junk? Snapping the shutter or pressing the cable release is not an athletic act, so I don’t have to warm up doing it, and you shouldn’t either.

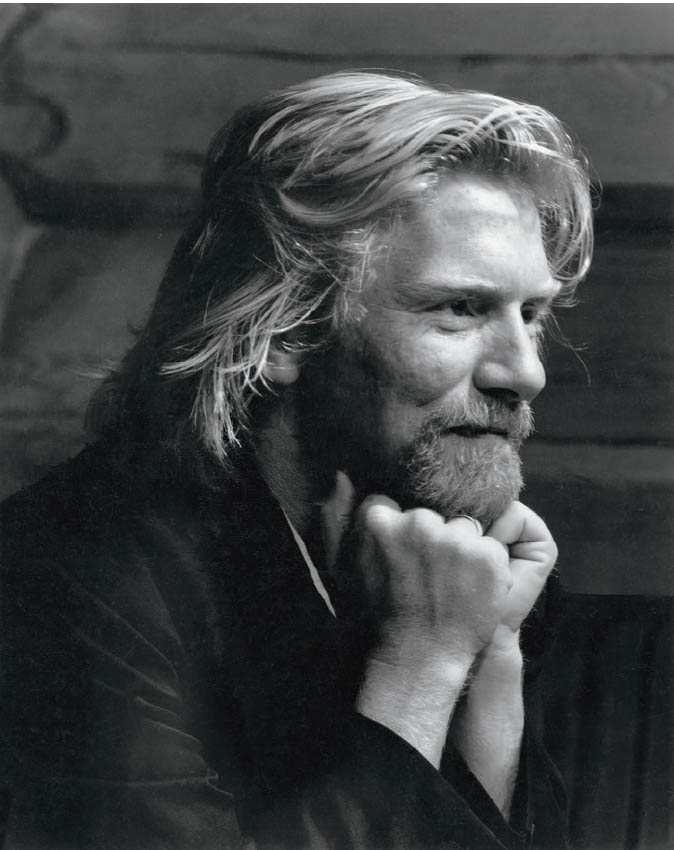

Figure 1-3: Morten Krovgold

One of the world’s truly great photographers, Morten struck me as a marvelous portrait subject with his strong Viking-like facial characteristics. But what would be the best angle to photograph him, and what type of lighting would convey that feeling most effectively? I finally decided it was the strength of his near profile. That evening, under the dim light of a chandelier, he propped his chin on his hands with his elbows on a low table for the 25-second exposure. Deep background tones surrounding him increase the feeling of strength.

But once I get that spurt of adrenalin, I work hard to find the best camera position, use the most appropriate lens, choose filters for optimum effect, take light meter readings or carefully check the histogram, and expose the image with great care using the optimum aperture and shutter speed. All of these things are important and require thought and effort. The initial response to the scene is spontaneous, but the effort that follows is not!

I believe this approach is valid for photographers at any level of expertise, from beginners to the most advanced. When you find something of importance, it will be apparent. It will be compelling. You will feel it instantly! You won’t have to ask yourself if it interests you, or if you are enthusiastic about photographing it. If you don’t feel that spontaneous motivation, you will have no desire to communicate what you feel.

On the other hand, I think the prime motivation for most snapshots is either the knowledge that someone else wants you to take the picture, or your own desire to take it to show where you have been. Neither of these motivations are concerned with personal interpretation or with personal expression, and neither have that internally compelling aspect. Photographs like these, where you’re standing at the sign to the entrance of Yellowstone National Park—probably just to prove that you were really there—or nearly one-hundred percent of selfies, are pure fun, memory-laden images, but have little or no artistic merit.

![]() I’ve worked in the darkroom until 3, 4, or 5 a.m. These are not things you do for money, but for love.

I’ve worked in the darkroom until 3, 4, or 5 a.m. These are not things you do for money, but for love.

It has long struck me that people who attempt creative work of any type—scientific, artistic, or otherwise—without feeling any enthusiasm for that work have no chance at success. Enthusiasm is not something you can create. Either you have it or you don’t! True enough, you can grow more interested and enthusiastic about something, but you can’t really force that to happen, either. If you have no enthusiasm for an endeavor, drop it and try something else. If you are enthusiastic, pursue it! Just be honest with yourself when you evaluate your level of enthusiasm.

![]() It has long struck me that people who attempt creative work of any type without feeling any enthusiasm for that work have no chance at success.

It has long struck me that people who attempt creative work of any type without feeling any enthusiasm for that work have no chance at success.

Ask what you are drawn to, what intrigues you. Most likely you will take your best photographs in the fields that interest you when you have no camera in hand. If you are deeply interested in people—to the point of wanting to know them thoroughly, what really makes them tick—it’s likely that portraiture will be your best area. If you want to know more about people than their façades, it would follow that, with camera in hand, you will dig deeper and uncover the “real” person. While I don’t consider myself to be a portrait photographer, I’ve made some portraits of people I know and like, that have been meaningful to me (Figure 1-3).

Figure 1-4: Ghost Aspen Forest

Soft, hazy sunlight made this photograph possible. Bright sun would have been too harsh for the delicate tones I sought. The bleached branch at the lower right maintains the lines and movement of the diagonal trees. The rippled reflections were more interesting to me than a mirror reflection would have been because they reflect only the vertical trees, not the diagonals.

Are you excited by passing events, or by action-filled events, such as sports? Are you fascinated by the corner auto accident, the nearby fire, the dignitary passing through town today? If so, you may be inclined to photojournalism or “street photography.” The latter term encompasses a wide cross section of candid photography that was elevated to an art form by Henri Cartier-Bresson, Weegee, and others. The approach differs greatly from formal portraits in that the subject matter is usually unrehearsed and often unexpected. This type of photography (which is certainly a form of documentary photography at its best) is geared to those who seek the unexpected and transitory.

Consider a further aspect of this pursuit: the most incisive efforts in this realm often don’t concentrate on the event per se, but rather on the event’s effect on the observers or participants. In many cases, emphasis on human reaction and interaction reveals more about human nature—and about our world—than the occurrence itself. Straight photojournalism is all too often involved with the event, and only on rare occasions rises to the insightful commentary that transcends mere recording to become true art.

Are you stimulated by pure design, or by color arrangements? Perhaps abstraction is suited for you. Brett Weston was a prime example of a classically oriented photographer using the “straight silver print” and abstraction applied to almost any subject matter. Experimental pursuits such as multiple exposures, photomontage, double- and multiple-printing, solarization, non-silver methods, the nearly infinite digital opportunities for subtle or radical manipulations, and any other conceivable approach is fair game in this realm. The only restraint is your lack of imagination or your unwillingness to experiment.

Perhaps your interests lie elsewhere. Analyze them. If you cannot define your interests, try your hand at a number of these alternatives and see which appeal to you most and which least.

I have evaluated my interests, and it may prove instructive to see what I have found. Today I photograph a wide variety of subjects, but I started from a more limited base. Initially nature was my sole interest. Slowly my interests grew to include architectural subjects and then branched out widely within both of those broad subject areas, while making forays into other areas. As Frederick Sommer once said, “Subject matter is subject that matters!” I realized that there was no reason to limit myself unnecessarily.

My initial interest in nature was all-inclusive. I was (and still am) drawn to trees, mountains, open fields, pounding rivers, tiny dewdrops at sunrise, and millions of other natural phenomena. I am fascinated by weather patterns and the violence of storms, the interaction of weather with landforms, and the serenity of undisturbed calm. Geology excites me, and I feel awed by the forces that create mountains and canyons. All of these phenomena appear in my photographs along with my interpretations, my awe, my excitement. Without a camera I would still exult in them. With a camera I can convey my thoughts about them. Then others can respond to my thoughts, my interpretations, my excitement.

In 1976, near Yosemite National Park, I came across a grove of aspen trees killed by flooding from a beaver dam. The pattern of dead trees was remarkable, but the bright sunlight was too harsh to allow a photograph. However, my familiarity with weather patterns in the Sierra Nevada, and my observations of cloud patterns that day indicated a storm could be coming within a day or two, and that if I were to return the next day I might be lucky enough to obtain a photograph under hazy sun or soft, overcast lighting. As expected, by noon the next day a layer of thin clouds—the immediate precursor of the storm—softened the light and I made my exposure. My interest in weather helped me make the photograph I wanted (figure 1-4).

A strange-looking landscape and my interest in natural history drew me to take a series of short hikes—once or twice a day—in late 1978 and early 1979 through an extensive area of the Santa Monica Mountains in Southern California that had been burned by a chaparral fire. Starting two weeks after the fire, my walks took me to unusual vistas, through the velvety blackness of mountains and valleys, and, in time, through the spectacle of rebirth as the region burst into life again (figure 1-5). I chose ten of the photographs made during that four-month period for a limited edition portfolio titled “Aftermath.” The photography ended up as a major project, but it began as a sideline to my interest in the natural history of the region under special conditions.

Figure 1-5: Raccoon Tracks

The cracked mud of a drying streambed held the paw prints of a raccoon, the first sign of life I saw in the burned landscape, bringing tears to my eyes. It was a joyous indication that some of the local residents had survived the fire.

In 1978, I began photographing a fascinating set of narrow, winding sandstone canyons in northern Arizona and southern Utah, the slit canyons, and my lifelong interest and educational background in mathematics and physics has greatly colored my interpretation of them. I view their sweeping curves as those of galaxies and other celestial bodies in the process of formation. The lines and the interactions of forms strike me as visual representations of gravitational and electromagnetic lines of force that pull the dust and gases of space together to form planets, stars, and entire galaxies, or the subatomic forces that hold atoms and nuclei together. To me, a walk through those canyons is a walk through billions of years of evolving space-time, and I have tried to convey that vision through my photographs (figure 1-6).

Figure 1-6: Hollows and Points, Peach Canyon

I see the gracefully sweeping lines of the slit canyons as metaphors of cosmic forces made visible, as if we could see gravitational or electromagnetic lines of force. If we could see those forces between heavenly bodies (stars, galaxies, planets, etc.), rather than seeing the heavenly bodies themselves, they may well look like this. I feel that this photograph contains particularly elegant and enigmatic examples of this effect, with sculptured lines so lyrical that it would make a Michelangelo or Henry Moore jealous with envy.

Figure 1-7: Nave From North Choir Aisle, Ely Cathedral

A series of compound columns, arches, and vaults frame the distant portions of the cathedral, with still more arches and columns, indicating even more around the bend. Indeed there are more. The unity of forms amidst the complexity of the architecture is a vivid example of Goethe’s statement that “Architecture is frozen music.” This is also an example of positive/negative space in which the nearby columns and archways form the positive space, and the distant nave the negative space.

Figure 1-8: Chicago, 1986

Seven different modern skyscrapers huddle together in downtown Chicago, creating interesting interactions within the geometric sterility of each. Somehow these giant urban file cabinets can become visually interesting when viewed in relation to one another.

Over time, I recognized that many of the same facets of nature that intrigue me are also present in architecture. Architecture can be awesome and uplifting; it can supply fascinating abstractions and marvelous lines and patterns. It often can be photographed without the need for supplementary lighting, and in that respect it is much like nature and landscape photography. Turning my attention to manmade structures was an inevitable expansion of my interests.

After ten years of commissions in commercial architectural photography, my first major effort at architectural subjects for my own interpretation came in 1980 and 1981: the cathedrals of England. Prior to my first cathedral encounter, I would have had an aversion to photographing religious structures; it’s just not my bag. But upon seeing them for the first time, I was awestruck by their grandeur. My deep love of classical music crystallized my interpretation of their architectural forms as music—as harmonies and counterpoints, rhythms and melodies—captured in stone. I also saw the architecture in mathematical terms, as allegories on infinity, where nearby columns and vaults framed distant ones, which in turn framed still more distant ones in a seemingly endless array. I altered my flexible itinerary to see as many cathedrals as I could during my two-week visit, then returned in 1981 for five more weeks of exploring, photographing, and exulting in these magnificent monuments of civilization (figure 1-7).

As time went by, my interest in architecture—specifically, in large commercial buildings—led to a continuing study of downtown areas in major cities. This series, too, draws on my mathematical background, for I am drawn to the geometrical relationships among the buildings and the confusion of space caused by the visual interactions of several buildings at once. I find this aspect of my urban studies appealing (figure 1-8).

But my response to modern urban structures has another side, too. Unlike my positive reaction to cathedral architecture, I dislike the architecture of all but a very few commercial buildings. They are cold, austere, impersonal, and basically ugly. I feel that these giant downtown filing cabinets are built for function with little thought given to aesthetics. To me, they are the corporate world’s strongest statement of its disinterest in humanity and its outright contempt of nature. I have attempted to convey those feelings through my compositions of their stark geometries.

Over the years, my work has grown increasingly abstract. It has become bolder and more subtle at the same time: bolder in form, more subtle in technique. My subject matter will likely expand in the future; I will look further into those subjects that I looked at in the past, bringing out new insights that I missed the first time. Such growth and change is necessary for any artist, or stagnation and artistic senility set in.

I have come to recognize a very surprising fact: subject matter ultimately becomes secondary to the artist’s seeing, vision, and overall philosophy of life and of photography. This is not to imply that subject matter doesn’t matter. It surely does! It’s the subject matter that’s important to you that lured you into photography in the first place, but once ensnared, it turns out that your specific vision (i.e., the way you compose your images) will prove to be unique. There is a one-to-one equality between the artist and his art. A photographer’s way of seeing is a reflection of his entire life’s attitude, no matter what the subject matter may be. Only Edward Weston could have made Edward Weston’s photographs; only W. Eugene Smith could have made W. Eugene Smith’s photographs; only Imogen Cunningham could have made Imogen Cunningham’s photographs, etc. This is true because each great photographer has a unique way of seeing that is consistent throughout the artist’s entire body of work.

It would be of value to you as a serious photographer to delve into the question of why your interests lie where they do, and why they may be changing. Such evaluation is part of getting to know yourself better and understanding your interests more fully. It’s part of successful communication. Start with your areas of highest interest and stick with them. Don’t worry about being too narrow or about expanding. You will expand to other areas when you are compelled internally to do so—when something inside you forces you to make a particular photograph that is so very different from all your others.

Judging Your Own Personal Response

The second of the two personal considerations is more difficult. How do you respond to your interests and how do you wish to convey your thoughts photographically? This is a more deeply personal question than “What interests you?” It requires not only knowing what interests you, but also just how it affects you and how you would like viewers to respond to your photographs.

In the examples of my own work just discussed, I attempted to express a bit of this second consideration. The slit canyons overwhelmed me in a very specific way—as cosmic analogies, or as analogies to force fields—and my imagery is based on conveying that impression to others. Similarly, the cathedrals struck me as grand, musical, and infinite in their marvelous forms. Again, I tried to emphasize those qualities in my imagery. I did not simply conclude, “These things are interesting!” and begin to shoot, but rather I responded to the specific ways that I found them to be interesting. I approached them in an effort to express my strongest feelings about them photographically.

The next time you are photographing, think about your reaction to the subject. Are you trying to make a flattering portrait of someone you find unattractive or downright ugly? Unless you are taking a typical studio portrait (the “tilt your head and smile” type) you would do well to follow your own instincts. Does the subject strike you as cunning? If so, bring out that aspect. Is he or she sensitive and appealing to you? If so, try to show it in your portrait. Is the outdoor market colorful and carnival-like or is it filthy and disgusting? Emphasize the aspect that strikes you most strongly. Don’t try to bring out what others expect or want; emphasize your point of view! You may upset a few people initially, but soon they will begin to recognize the honesty as well as the strength and conviction of your imagery. But in order to do that, you first have to determine what your point of view actually is. It is not always easy to do so, because you may be struck by conflicting impressions, but it is essential to recognize such conflicts and choose the impression that is strongest.

An example may be instructive. Not long after World War II, portraitist Arnold Newman was commissioned to photograph Alfred Krupp, the German industrial baron and Nazi arms supplier. Newman was Jewish. He managed to get Krupp to pose for him on a small platform raised above the spreading floor of his factory, with the assembly lines below in a background. Fluorescent lights flooded the factory, and Newman augmented them with auxiliary lighting placed below Krupp’s face and almost behind him. He did not filter to correct the fluorescent color shift. Because the two of them were high above the factory floor, nobody else saw what was happening, and Krupp himself had no knowledge of photographic processes. The resulting portrait shows a ghastly, green-faced monster with ominous shadows crossing his face diagonally from below—the devil incarnate. Newman knew what he wanted and he understood his material. But I must also admit that the black-and-white version of this portrait is, to my mind, even more effective simply because the sick green color is missing. To me, that color goes overboard and pushes the envelope too far.

![]() As soon as I determine what I am responding to most strongly, and how I am responding, I must concentrate on emphasizing all the elements that strengthen that response, while eliminating those that weaken it.

As soon as I determine what I am responding to most strongly, and how I am responding, I must concentrate on emphasizing all the elements that strengthen that response, while eliminating those that weaken it.

A hypothetical example may also be valuable. As I wander through the canyons of the Kings River in Kings Canyon National Park, I am awed by the towering granite cliffs and pounding cascades. Yet I am also struck by the softness and serenity of the grassy meadows and sun-streaked forests.

If I were to make just one photograph of the area, I would choose the aspect I wished to accentuate: its overall awesomeness or its more detailed serenity. I doubt that I could successfully convey both in one photograph. Am I more strongly drawn to the spectacular or the serene? I would study the cliffs and cascades to determine if they truly are as spectacular as I first perceived them to be. And are the forests and meadows as serene? Am I looking for the spectacular, let’s say, and straining to find an example when none actually exists? In other words, am I stretching too far for a photograph? I must make proper assessments of these questions in order to produce a meaningful image that can communicate my feelings.

As soon as I determine what I am responding to most strongly, and how I am responding, I must concentrate on emphasizing all the elements that strengthen that response, while eliminating (or minimizing) all those that weaken it. Basically, I am responding to the mood the scene evokes in me, and I must determine how I wish to convey that mood through my photography. The feeling my photograph evokes is my editorial comment on the scene. If the response is what I intended, I have communicated my thoughts successfully. If the response is the opposite of my intent, I may be disappointed but subsequently come to feel that the interpretation has some validity. It may even open up new insights to me. However, if my photograph evokes nothing in others, I have failed miserably.

In the future, I may look at the same scene and work toward conveying a different thought. Why? Because of changes in my own perception as time goes by. My interpretation will change. My “seeing” will be different. My goals will be different.

You, too, will doubtless change over time, as will your approach to photography. But if you are like me, you will find that these changes will not invalidate your successful earlier efforts. A fine photograph will survive the test of time. Beethoven would not have written his first, second, or third symphonies in the same manner after completing the final six, but that does not invalidate the earlier scores.

Though your perceptions will change, it is of utmost importance to be in touch with them at all times. Your perceptions and your internal reactions set the direction for your photography, your visual commentary. Get yourself in tune with those reactions. In other words, get to know yourself. But one word of caution: don’t analyze yourself to death. There is a reasonable limit to introspection. Before getting hung up on it, start communicating by making some photographs.

Successful communication of your message is the essence of creative photography. Reporting the scene is shirking your responsibility; interpreting the scene is accepting the challenge. Though the scene may or may not be your creation, the photograph always is (figure 1-9)! So don’t just stop with the things you saw; add your comments, feelings, and opinions. Put them all into the photograph. Express your point of view. Argue for your position. Convince the viewer of the validity of your conclusions.

Understand what you want to say!

Understand how you want to say it!

Then say it without compromise!

Now you are thinking in terms of creative photography!

Of course there are those who will say that an artist is searching for the truth, and it is foolish to be so adamantly positive about your approach. There is some validity to this objection, but in general, I think the idea of “searching for the truth” is a highly romanticized notion. I believe that each artist, like everyone else, has strong views about the world: what it is, what it should be, and how it could be improved. As such, I think that most artists are not so much searching for the truth, but searching for a proper method of expressing the truth as they see it. It should be manifestly obvious that Lewis Hine was not searching for the truth, but revealing the grim truth of conditions in factories employing child labor. Similarly, Ansel Adams was not searching for the truth in his nature photography, but expressing the truth about the beauty and grandeur of nature as he saw it.

The list can go on and on, but the point should be clear. Even if we go back in time long before the start of photography, we see similar examples of artists expressing the truth rather than searching for it. Michelangelo depicted prominent local officials as being cast into Hell in some of his famous murals, a bold comment for which he suffered mightily. Other prominent artists, composers, and writers have been equally bold in their truthful statements.

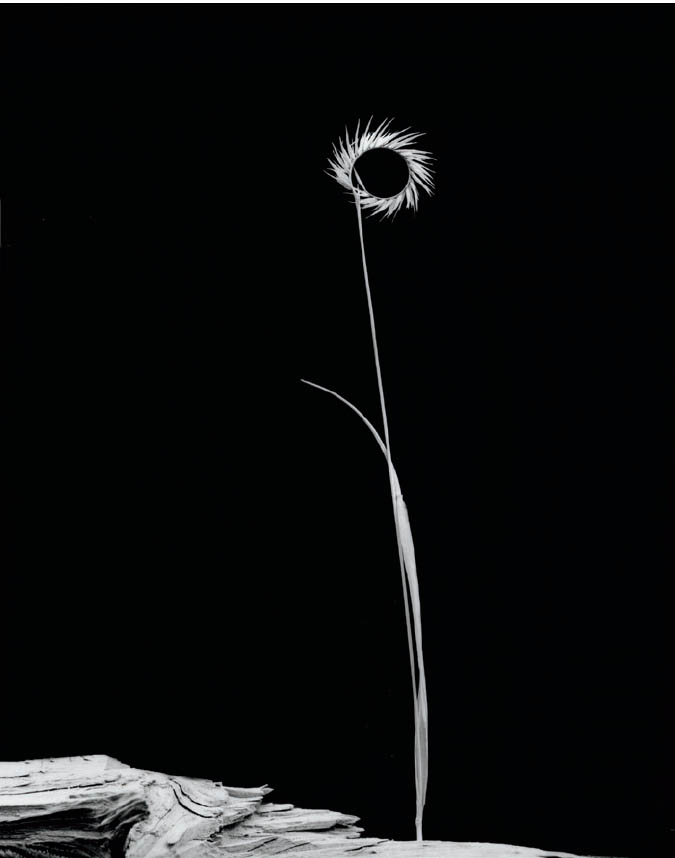

Figure 1-9: Grass and Juniper Wood

Blue grama grass, rarely more the five inches tall, grows on the near-desert soils of Utah, usually with a crescent-shaped tuft at the top. I found this one with a full ringlet. As high winds shook it wildly, I pulled it up for later photography. Within a few steps I found a small piece of juniper wood with a cleft, to serve as a pedestal for the grass. I knew exactly what I wanted to do with these objects. Two days later, when the wind died down, I stacked two ice chests in front of my truck where I was camping, put the grass in the wood cleft, placed it atop the ice chest, and focused my 4 × 5 camera. I then laid the black side of my focusing cloth on the hood of the truck, hanging down over the grill to serve as the background.

Beyond that, there is no such thing in our complex world as “the truth,” but rather many, many truths, some of which conflict with others, and some of which contradict others. Thus the truth is elusive at best, and nonexistent at worst. Each of the subjects I have photographed, for example, has revealed different aspects of the world that I have found worthy of commentary. If my photographs have not revealed the truth, at least they have attempted to express my point of view about each of those subjects. I can only hope they provide interest, meaning, and insight to others.

![]() Most artists are not so much searching for the truth, but searching for a proper method of expressing the truth as they see it.

Most artists are not so much searching for the truth, but searching for a proper method of expressing the truth as they see it.