9

Hebb’s Rule and Cognitive Rehearsal

I never questioned repetition until now.

—Teacher

Donald Hebb was a consummate teacher. Even in his early career at age 24, he experimented with methodology to eliminate drudgery and improve academic outcomes. Intuitively, he was convinced that the school experience that he was asked to deliver did not serve his students well. Having witnessed children of all intellectual abilities fail, he was convinced that the system was not in sync with how they best learned. In his own school days, he survived the vestiges of a pseudo-British “class” structure, which he considered mired in punitive practice that further damaged children’s motivation to learn. In the 1920s, Montreal’s education system reflected a neo-colonial mish-mash of “payment by results” and “monitorial” rote. Punishments were meted out liberally for behaviors that contravened the school’s ethos. Assuring his students that education was a privilege, Hebb shifted from teaching by “lecture” to a co-created model by “flipping” the class. He did away with homework. In his own words, “Students were NOT punished for inattention and those who disrupted the class were sent outside to PLAY (78).”

After a brief interlude in formal classroom education, Hebb returned to scientific research on his favorite subject—the brain. He expanded his thinking in relation to pedagogy by deepening his connection to the biological basis of behavior. Being excited by neuro-physiological behavior, he sought to understand how the function of neurons contributed to psychological processes such as learning. Inspired by early successes, he devoted energy to enhancing the connection between pedagogical knowledge and neuroscience. Hebb was one of the earliest neuro-educators who believed that all behavior was the result of brain function (79).

Hebb Abandons Behaviorism

The educational world was struggling with an emergent behaviorist agenda that had sprung from the stimulus response laboratories of Pavlov, Thorndike, Watson, and BF Skinner. Skinner’s radical behaviorism was prominent in Hebb’s day, and called for a rejection of introspection by refuting mental and subjective experience. In Skinner’s view, laws that were determined by a rigorous application of stimulus/response inquiry could explain all human behavior.

Hebb had already witnessed lesions in brain regions of psychiatric patients and was headed in a different trajectory. His educational experience in the classroom only served to solidify his medical experience in the surgical laboratory. The study of patients with brain injuries had convinced Hebb that it was the brain that explained behavior, and that teaching adolescent learners involved a journey into brain regions specific to consciousness, attention, perception, thinking, and emotion. Today, Hebb is recognized as a pioneer in the field of cognitive neuroscience. Gazzaniga, who established the field of split-brain research at the University of California, further describes him as the key individual who exposed behaviorism for its negative impact on education (29). Speaking about Hebb’s 1949 publication Organization of Behavior: A Neurophysiological Theory, he states:

Not everyone understood how radical behaviorist thinking was changing the learning world. The neat unified theory that behaviorism offered wasn’t passing muster with neuroscientists.

In a previous chapter, we pointed out that George Miller had rejected Skinner’s external stimuli/response outcomes. He, too, was convinced that the primacy of innate mental capacities would win out. In the following account, Miller describes how he ended up (along with Hebb and Chomsky) in a counter-revolution, which we now recognize as the cognitive revolution. The jargon didn’t work! (80)

Scientists like Miller, Hebb, Simon, and Chomsky moved quickly beyond behaviorism, advancing their respective fields away from stimulus and response thinking.

Meanwhile, behaviorism embedded itself even deeper into education. In the following year, 1957, when Sputnik forced a reevaluation of American connection to math and science, the drive to win the race for dominance colored everything educational. Schools were key. Without considering any alternatives, behaviorist teaching methods became entrenched deeper into American education systems. The race was on. Some call it the race to the bottom. This might be the single great tragedy of schooling in the 20th century—to miss the cognitive revolution primarily at the conceptual level and, specifically, in practice.

A Biochemical Correlate

Hebbs’ central thesis has implicit meaning for every teacher in every classroom. His notion that there is “a biochemical correlate for everything that people think, feel, remember, say, and do” is central to teacher preparation courses (78). From that standpoint, all conversations concerning a child’s “bad behavior” are entirely out of place and, specifically, if they preempt progressive punitive practice.

In an amygdala hijack scenario, behavior is not “bad;” it is ‘expected.’ From Hebb’s neural vantage point, all children want to excel in school, to be successful, and achieve success both academically and socially. But, if the conversation is about “bad behavior” instead of amygdala hijack; about punishment instead of strategies for increasing working memory; and about threats and consequences instead of brain derived neurotrophic factor, then the teaching profession is out of synch with Hebb’s world of neural plasticity, long-term potentiation, and cognitive rehearsal.

Cognitive neuroscientists since Hebb’s day have advanced the field by reaffirming his findings (81). With the use of advanced imaging techniques, they demonstrate the impact of impoverished environments on children’s brains. Children who grow up in trauma, who suffer neglect, and who live in fear and hyper-vigilance develop smaller brains with less dendritic arborization (37). In the classroom, such a child will appear with “behavior” problems that look like disruption, aggression, and willful destruction. A neural educator knows how to use mirror neurons, neurotransmitters, and chunking to help any child co-regulate first and then grow structures that the brain requires for academic success.

Hebb’s inspiration was grounded in children’s play. In particular, he learned from his two daughters’ play with pet rats that were running freely around their home. Given what he knew about running rats through mazes at his laboratory at McGill University, he pondered the question: “Are the rats who play with my daughters different from those isolated as caged animals at the office?” He realized that the brain was changing in response to environmental interaction—what we know today as epigenetics. Hebb’s question set in motion a research trajectory that changed the lives of children and classrooms everywhere.

Teacher Talk

Strategies for Change

Several strategies that are Hebbian in character are easy to introduce to the classroom or Zoom classes for social distancing spaces.

Simple Strategies

Replace the word “Repetition” with “Cognitive Rehearsal.” Repetition is always meaningful for learning. We know that rote works. One and One is Two, One and Two is Three, and so on, helps us sing our “tables” so that over time we can recall the answer to complicated math in automaticity. When the brain is in automaticity, we free up working memory so that there is more room for other more immediate processing. Cognitive rehearsal trumps repetition every time.

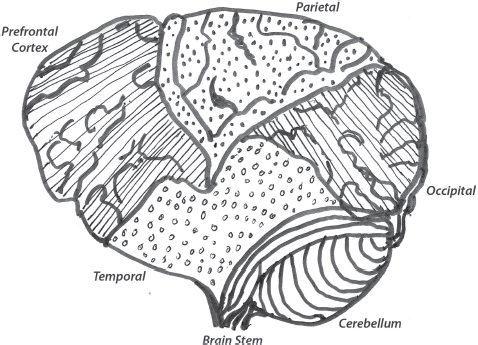

When we think about Hebb’s idea of neurons communicating with each other and that the presynaptic events on the first neuron can increase postsynaptic receptors on the connecting neuron, then we can be more intentional about how we engage the child’s lobes with respect to a particular new concept. Figure 9.1 illustrates the cerebellum and four lobes. Cognitive Rehearsal will involve vision (occipital), listening and talking/arguing (temporal), movement and balance (cerebellum), small-motor skills and emotions (parietal), and the executive higher-order thinking and planning (prefrontal cortex). Cognitive Rehearsal initiated with intention can grow and strengthen structures that facilitate learning with deep understanding.

Advanced Strategies

Visualize each child in your class. Could you right now name three other people (assuming that you are one) who you consider are solid support people for that child? Each child requires four supporting adults to ensure safety, confirmation, reinforcement, and fun. Think outside the faculty room (you might have to think outside the home also). Yes, it might be that some kids will have four faculty that they know will support them; you might include a bus driver, a sporting coach, a cafeteria worker, a janitor. It matters less what they are; it matters more that the child has a trusting, supportive relationship with at least four caring adults.

Summary

In this chapter, Dr. Hebb walked into our classrooms. If for the first time, then the change will be expressly momentous. The notion of Cognitive Rehearsal replaced Repetition. If his ideas about “neurons that fire together wire together” has already been in your classroom, then perhaps you were able to increase your knowledge about plasticity: to imagine maladaptive impact as opposed to beneficial consequences. Each brain is only three pounds, and it is all the child has. It is enough. In the next chapter, we will explore further the world that Dr. Hebb set in motion; that of neural adaptation, cell assemblies, and structural and functional plasticity, by introducing Marion Diamond, the neuroscientist who measured Einstein’s brain.

Vocabulary

Structural Plasticity, Cognitive Rehearsal, Dendritic Arborization