3_______________________________________________________

The provision and supply of

conference venues____________________________________________

The aims of this chapter are:

- 1 To examine the range of conference venues and to highlight the different characteristics of each.

- 2 To explore and quantify the geographic spread of conference venues within Britain and Ireland in terms of a regional analysis and regional variations.

- 3 To examine the nature of the ownership and management of conference venues in the light of funding and organizational issues in general.

3.1 Introduction

In the first chapter we referred to the history and development of conference venues and the attempts by interested bodies, such as consultants and academics, to classify them. Some of these classifications do not adequately explain the characteristics of the various venue types. However, an exploration of characteristics is a necessary step in the exploration of the structure and components of the supply side of the conference business. For the benefit of students, current examples are given which may serve to assist understanding of the classification. There are elements of overlap between the classifications and it should be noted that the classification is intended as a ‘modus vivendi’ (or put more simply, the classification will develop as time goes on), not as the last word.

In addition to the classification, an analysis has been carried out of published information, notably the ‘Conference Blue Book’ to attempt to quantify the geographic spread of venues. Each (UK) region is identified with a percentage of venues as a proportion of the whole and, where possible, the number of large-scale venues are noted (large scale being defined as a centre capable of accommodating 1000 or more people) together with an identification of purpose-built conference centres in each region, where these are known.

Clearly there are limitations to this type of analysis as the published or advertised information about venues represents only a fraction of the actual total. Related to this constraint is the issue of ‘when is a conference centre not a conference centre’, given that, arguably, any room capable of taking two people round a table for a small fee could be classed as a conference venue.

Conference centres are not evenly spread throughout the country; this is partly a function of demand, partly a function of existing infrastructure and competition, and partly a function of the need or ability of a town, city or resort to develop conferencing as part of the economic provision of that place. Large conference centres provide employment and other economic benefits, but they are not the only means of doing this; in consequence, given limited funds, a council or other public or private body may decide that a conference centre may not be the only economic option possible in their location.

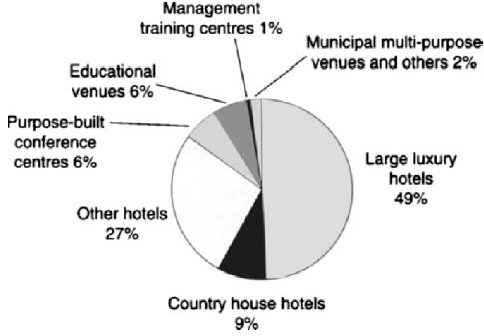

Conference centres, which, in general terms, can be seen as a homogeneous business activity, vary considerably in their development and original funding. The largest centres are often a product of combined public and private sector funding and play a role in the economic well-being of a city, town or resort area. Funding and origins do vary from sector to sector and as a consequence, each sector is taken individually. Essentially, funds for the development of a conference venue may be obtained on the open market, that is to say via banks and shareholder investment; or via public sources such as city councils, government (or the European Union), or national funds, including the lottery, sports and arts councils, depending on the type of development. In a very limited number of cases, a conference centre may be privately owned by a single individual or small group of individuals. Regardless of who owns the venue, we can see the proportion of the total market that different venues hold in Figure 3.1.

Whatever the ownership, management structure or proportion of the total business a conference venue has, the primary objective of its development is likely to be the generation of wealth. This depends on there being an adequate market for the centre’s services (poor market feasibility analysis may result in a centre being opened where there is inadequate demand, resulting in bankruptcy and closure) and/or the effectiveness of the management of that centre. As with hotels, the management of a centre may make all the difference to its profitability (Lundberg, 1994) but as centres have high capital costs, so the market demand and general state of the economy are also important.

Source: Coopers and Lybrand Deloitte, 1990

Figure 3.1 Percentage share of delegate days by type of venue

3.2 The range of conference venues and their

ownership and management

Fundamental to any examination of the issues of ownership and management of conference venues is an understanding of the differences between ownership, on the one hand, and management on the other. While the difference is generally clear to the experienced observer, it is often less so to the student. In former days, and for small organizations, the ‘ownership’ and ‘management’ were often the same. The person who ran a small inn with a meeting room, in a country town, both owned the property and managed the business, many still do. The larger the business, and many conference venues are very large businesses indeed, the more likely and necessary the separation of ownership and management becomes. It should also be considered that a particular venue may not fall conveniently into a particular class. The major classes are, for our analysis, as follows.

Purpose-built conference centres

These centres are the ones that probably spring to mind when the words ‘conference centre’ or ‘convention centre’ are used. In general, these venues are large, modern, high profile and constructed by a municipality or dedicated company with a view to profit or the economic benefit to the community (Fenich, 1995). Of these, there are a number which are particularly well known: the International Convention Centre (ICC) in Birmingham, the Harrogate International Centre and the Conference Forum in London are examples. The ICC includes Birmingham Symphony Hall, home of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. The Harrogate International Centre is one of a number of purpose-built centres constructed to rejuvenate resort or spa towns. The Conference Forum contains the Chaucer Theatre and was intended to contribute to the community life of the Aldgate area of the city of London. Such purpose-built centres are often, therefore, extremely significant to their areas, both in economic and social terms. They are thought of as the flagships of the conference business and there are fewer than 30 in the whole of the UK, and none in Ireland, whose principal business is conferencing. Owing to their purpose-built nature, they are generally technically advanced, have large auditoria and good support infrastructure such as parking and loading facilities.

Historically, purpose-built conference centres were often developed out of some civic initiative (i.e. by a local or regional council). They were often intended to play a role in maintaining a town’s economic future, so some of the older purpose-built conference centres were developed and owned by the councils themselves, particularly in resort towns. As demand for larger-scale venues increased, however, civic funds were limited and town councils were no longer in a position to develop centres from their own funds. Various partnership arrangements were created in order to build and operate conference centres, where centres were needed for a public purpose, such as economic development or regeneration, but money came from other sources, mainly the commercial sector, with possible input from the European Union or the National Lottery. The International Convention Centre and National Indoor Arena (NLA) in Birmingham can be used to illustrate this type of ownership. Both land and buildings are owned by Birmingham City Council, but are operated by a management company, NEC Ltd, the share capital of which is owned equally by the City Council and the Birmingham Chamber of Commerce. The capital funding of the ICC was composed of a loan stock issue of £130 million via NEC Ltd and a further £50 million grant from the European Regional Development Fund (EU). In contrast, the NIA capital funding was comprised of £22 million from the city council, £3 million from the UK Sports Council and a private development company (Shearwater) providing £25 million (Law, 1993; NEC, 1996).

Municipal multi-purpose centres

The construction or development of a purpose-built conference centre is hugely expensive. As a consequence, the cost, even taking into account large private sector funding, is beyond the ability of most municipalities (towns) to promote, or indeed to justify in terms of demand. It is therefore often the case that a town or city will construct a multi-purpose facility or reuse a former civic building as a conference venue. There are a number of excellent examples of such multi-use: the Dome in Doncaster provides conferencing, leisure facilities, sports facilities and a wide range of subsidiary activities. It is a new purpose-designed venue, of a type (or approach) found in other locations such as the Plymouth Pavilions or the Aviemore Mountain Resort. A less costly approach to the type of venue is that adopted by locations such as Eastbourne, whose Devonshire Park Centre comprises a historic Winter Garden and the Congress Theatre; or the Albert Halls in Bolton, developed from a former hall of the formidable Victorian stature and civic pride so often found in the towns and cities of Northern England and Northern Ireland. Venues of this type are often of a high standard, but occasionally limitations in the public purse (council funds) result in a lack of investment, implying that some multi-purpose centres may not exploit their full potential.

The ownership and management of this class of venues are similar, in some respects, to those of the purpose-built conference centres. They are largely funded by councils, but increasingly with some of the money provided by private sources, including developers, and, in a few cases, by the National Lottery or European Union. Management, as a generality, is of two kinds: in-house (i.e. managed as a department of the council) or via a management company set up by the council and its partners. In a few cases, these centres may be run by an operating company on a contractual basis, e.g. a facilities management company with interests in the leisure/hospitality or arts field. The Dome at Doncaster is probably the largest example in the UK. It was opened in 1989 at a cost of £25 million, and funded by Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council. It provides not only conference facilities but also extensive leisure pools, split-level ice rink, a beauty therapy suite, fitness facilities, a bowls hall, a 2000-seater events hall and a forum area for exhibitions and special events. It is estimated that the Dome has also attracted some £20 million of additional inward investment to the immediate area. The Dome is run by a private limited company together with a group of trustees from the council and community who oversee general policy (Dome, 1994).

Residential conference centres and in-company facilities

A number of this type of centre exist; they are, if not purpose-built, at least purposely converted, often from buildings of some architectural distinction. Most are operated by private companies, whose raison d’être is management development or conference centre provision as a commercial activity. The standard of the upper echelon of such centres is extremely high; there are, however, a number of centres whose raison d’être is more management development in an activity sense, i.e. not entirely classroom based but involving outdoor activities of various kinds. Examples of the former are the Sundridge Park Management Centre in Bromley and the Ashridge Management College in Berkhamsted. Examples of the latter are often found in National Parks, sometimes run by the Park Authority and having a purpose of, primarily, outdoor education; in these cases the facilities may be extremely basic and deliberately so due to the nature of their main function of outdoor education, or team building.

Similar in concept to many residential conference centres (though not always with residential accommodation), a large number of companies have their own in-company conference centres. These may range from relatively small on-premises facilities to large out of town venues, particularly for large national organizations such as banks, building societies and insurance companies (e.g. the BBC’s Wood Norton Conference Centre in Evesham and the Siemens Company Conference Centre in Manchester). These companies have a constant need for staff training and conferencing for whom full-scale in-company facilities prove more cost-effective than external venues.

Both these types of centres tend to be wholly owned and managed by the companies themselves, with a few being managed by operating companies. Residential conference centres may be very similar in ownership and management to the hotel sector. Hayley Conference Centres, for example, owning several residential conference centres in the South Midlands, bear a number of similarities to hotel-owning companies. In-company facilities, such as those used by the major banks or insurance companies for staff training purposes, are, in a few cases, operated by the companies themselves, but increasingly the operations and management are contracted out to an operator, typically one of the major contract catering companies such as Sutcliff, Aramark or Town and County.

Academic venues

A large number of universities and colleges provide conference facilities; this is particularly the case where such institutions seek to generate income during vacation periods, when their extensive provision of lecture theatres, technical facilities and residential accommodation is available for external use. In practice, summer conferencing is particularly important for many academic institutions and indeed a number of them provide not only summer use facilities but also dedicated conferencing facilities all year round. Examples include the Penthouse Conference Centre of the University of Durham, UMIST’s Manchester Conference Centre at Weston Hall and the Danbury Park Management Centre of Anglia University at Chelmsford. The list of universities and colleges offering conferencing is very long indeed. Academic venues are also, significantly, of considerable importance to the association market, due to cost competitiveness. While some academic venues offer extremely high quality conferencing and many, such as the University of Surrey and UMIST, are able to provide bedroom accommodation to an en-suite standard, many only provide student ‘study bedroom’ accommodation sharing communal facilities between conference delegates, one reason for the relatively modest cost.

Almost all academic venues are owned and managed in-house; this is chiefly due to them being used principally for educational purposes during the academic year, rather than as conference venues, year round. Most universities and colleges seriously involved in the business have a separate (though still in-house) conference office to deal with the business, though many rely on the provision of the services within the conference areas being dealt with by outsourced companies (e.g. contract caterers or facility management organizations). Conferences are, however, a major source of income to most universities and colleges; as a consequence, some of these have developed their conference business significantly and have sought external funding for the building of residential facilities and to improve the quality of their conference areas. Historically, academic venues sought to use their lecture rooms and halls of residence during vacation periods for the conference business, and this continues. On the other hand, an increasing number have sought some private sector funding to construct either complete year-round residential conference venues (such as UMIST’s Manchester Conference Centre) or to construct higher quality residential facilities with en-suite rooms for conference delegates (such as at the University of Surrey, University of Essex and elsewhere).

Hotels

The importance of hotels to the conference business must not be underestimated. Hotels are the largest single component classification of venue providers, with in excess of 70 per cent of the provision (Coopers and Lybrand Deloitte, 1990). Owing to this strength of provision, and the varying nature of hotels themselves, this class is sub-categorized into three: deluxe city centre hotels; country house hotels; other hotels.

Deluxe city centre hotels

To say ‘city centre’ is rather a misnomer, as we are really talking of any urban conurbation, some towns, some cities. The deluxe element is crucial and is chiefly in those establishments that the public would think of as four or five star rated. The range and diversity, even within the sub-classification, are considerable and the extent of the provision renders examples unnecessary - just pick up any hotel guide.

Country house hotels

As with the above, country house hotels are extremely diverse but, as a generality, are of a very high standard and are often located in their own grounds. The major development of country house hotels in recent years has been by conversion of former stately homes, some of which are both extremely historical and stupendously grand, some of which are more modest, but delighting in their rural setting. As with city centre hotels, the list is extremely long.

It is rather unfair to class all other hotels this way, but the sub-classifications could run into a very extensive list indeed, ranging from ancient inns, Georgian town house hotels and Victorian railway hotels to modern airport hotels - from the chain lodge to the family-run establishment. A very large number of hotels provide conference facilities, ranging from a single room to whole conference wings attached to large hotels. In particular, a number of the major hotel companies, such as Stakis and Mount Charlotte Thistle in Britain, and Jury’s in Ireland, concentrate on providing conference and leisure facilities in their business hotels.

It has been noted that the largest provider of conference venues is the hotel sector. Ownership of hotels runs from private individuals to major international public companies, whose shareholders own the business. In between these extremes are partnerships and private companies (large and small). Private companies have a limited number of owners, say a group of six people, for example, who have put money into the business. Public companies are those quoted on the stock market, whose ownership may be composed of a very large number of small shareholders or some large shareholders and shareholding institutions, such as pension funds. The activities of these various types of owning groups (companies) vary, even in the hotel sector. Some are purely hotel owning or operating companies such as Jarvis and Inter-Continental; some have hospitality businesses in related sectors, including restaurants and other service activities, such as Granada and Whitbread; some have major interests in non-hospitality businesses, such as Virgin, First Leisure and Ladbrokes. Clearly, ownership and management also vary, even within this apparently unified sector. Companies with hotels (and therefore conference interests) may both own the property and manage it; alternatively, they may not own the property, but own the brand name and act as operators by contract to the property owners; or finally, they may own the property but have another organization manage it by operating contract, franchise, leaseback or other specialist contractual arrangement.

Unusual venues

The final class is in fact ‘everything else’. This is not as simple as it seems. It includes any place with a room able to accommodate two or more people around a table for a meeting which either cannot be categorized anywhere else and/or has some unique feature as shown in Figure 3.2. The extent of the ‘unusual venue’ category is enormous. The demand by conference organizers and particularly from incentive travel organizers for a venue which is unique, whether that uniqueness is in a castle or a cave is extremely significant. Many venues of this kind also tend to be at the upper end of the price range.

• Ships - Car ferries to battleships

• Castles and country houses/stately homes - Warwick Castle to Castle Howard

• Sports venues - Race courses to dog tracks

• Gardens - Botanical gardens to Winter gardens

• Museums - Motorcycle museums to Madame Tussauds

• Entertainment - Coronation Street to Whipsnade Wild Animal Park

• Listed buildings - The Royal Pavilion, Brighton to the Old Palace, Hatfield

• Institutes - Chartered Accountants to the Royal Society of Art

• Theatres - Royal National Theatre, London to the Crucible, Sheffield

Figure 3.2 Examples of unique venues

The ownership and management of unusual venues are as varied as the class itself. However, it does contain a proportion of organizations not found in the other categories - charities. Whereas the majority of conference venues are owned and managed by commercial or quasi-commercial organizations, many unusual venues, particularly in the castles/listed buildings and museums categories, are owned and operated by charities and similar organizations such as, in the UK, the National Trust, National Parks authorities, heritage organizations and voluntary bodies, and comparable Irish organizations, including private individuals. Clearly, a number of charities do have specific commercial aims and departments responsible for revenue generation through retailing, catering or conferencing. Funding of refurbishment or new construction in this field is therefore from charitable income, investments or possibly in the UK, through bids to the National Lottery, Millennium Fund, Arts or Sports Councils and in Ireland, the Lotto or heritage agencies and similar bodies, with advice from regional tourism organizations.

3.3 Geographic spread of venues

It is probably impossible ever to count the total number of conference venues in Britain and Ireland. The reasons are similar in some respects to those true of the hotel industry - picking up any hotel guide may give the reader a view of the comparative order of magnitude of provision in one area versus another, but a simple comparison of the listing of a particular town in, say, the AA Guide and the Yellow Pages telephone directory of that town would prove the difference: a typical hotel guide will list only a small proportion of the total because many guides are a form of paid advertising, whereas the telephone directory should list every hotel, inn and guest house in a town. This comparison cannot easily be made for conference venues - the telephone directory does not list them in the comprehensive way that hotels are listed. The estimation of size and extent of conference venues as an industry can only be guessed at, but a comparison of the order of magnitude of provision in different areas can be achieved. The analysis here is based on data provided in the Conference Blue Book 1996 and from data supplied by the Convention Bureau of Ireland. The Blue Book guide lists approximately 4450 conference venues in the UK and a comparison, region by region, is possible.

3.4 Regional variations in provision

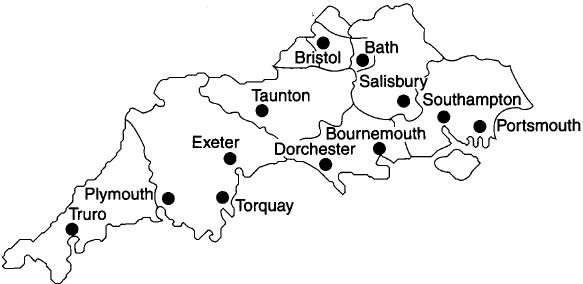

The South West of England (Figure 3.4)

Including Cornwall, Devon, Somerset, Dorset, City and County of Bristol, North Somerset, Bath and North East Somerset, Wiltshire, Hampshire, the Isle of Wight and the Channel Islands; 14 per cent of total venues, with 31 venues capable of accommodating over 1000 people (theatre style). Purpose-built venues include the Bournemouth International Centre and the Torquay Riviera Centre.

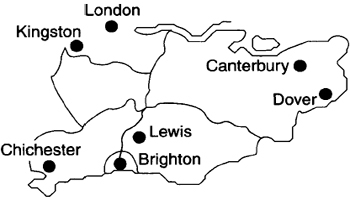

The South East of England (Figure 3.5)

Including Surrey, Kent, East and West Sussex (Brighton and Hove); 8 per cent of total venues, with 13 venues capable of accommodating over 1000 people. Purpose-built venues include the Brighton Centre.

Greater London (Figure 3.6)

Including the cities of London and Westminster and the London boroughs; 8.5 per cent of total venues, with 27 venues capable of accommodating over 1000 people. However, a number of these large venues are London theatres and thus the availability of space at appropriate times could be subject to restrictions due to performances. Purpose-built venues include the Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre, the Conference Forum, Wembley Conference and Exhibition Centre, the London Arena and the Barbican Centre.

Figure 3.3 Orientation of Britain and Ireland. Figures 3.3–13 identify county boundaries, county towns (if known) and locations identified in the text

Figure 3.4 The South West of England.

Figure 3.5 The South East of England

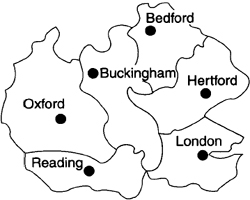

Figure 3.6 Greater London and the Home Counties

The Home Counties of England (Figure 3.6)

Including Hertfordshire, Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Oxfordshire and Berkshire; 7 per cent of total venues, with five venues capable of accommodating over 1000 people. There are no major purpose-built centres in this region, and for convenience the Home Counties were included as part of the ‘Midlands’ in the earlier section on regional demand.

Figure 3.7 East Anglia

The East Anglia region of England (Figure 3.7)

Including Essex, Cambridgeshire, Suffolk, Norfolk; 5.5 per cent of total venues, with nine venues capable of accommodating over 1000 people (of which four, by some curious circumstance, are in Great Yarmouth). There are no purpose-built venues here.

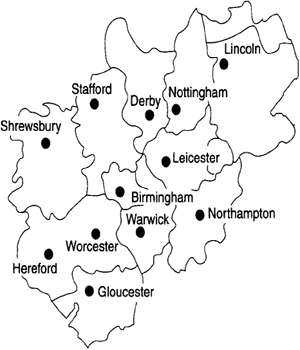

The English Midlands (Figure 3.8)

Including Lincolnshire, North Lincolnshire and North East Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, Northamptonshire, Leicestershire, County of Rutland, Staffordshire, West Midlands Conurbation (Birmingham, Wolverhampton etc.), Shropshire, Warwickshire, County of Hereford and Worcester, Gloucestershire; 15 per cent of total venues, with 34 venues capable of accommodating over 1000 people. Purpose-built venues: the International Convention Centre, National Exhibition Centre, National Indoor Arena.

Figure 3.8 The English Midlands

The North West of England (Figure 3.9)

Including Cumbria, County Palatine of Lancashire, Manchester, Merseyside, Cheshire; 11 per cent of total venues, with 30 venues capable of accommodating over 1000 people. Purpose-built venues include the GMEX Seminar Centre and the Bridgewater Hall, Manchester. Large-scale centres also include Blackpool Winter Gardens.

Figure 3.9 The North West of England

The North East of England and Yorkshire (Figure 3.10)

Including Northumberland, Redcar and Cleveland, Stockton-on-Tees, Middlesbrough, Darlington, Hartlepool, Tyne and Wear, County of Durham, City of Kingston-upon-Hull, City of York, North Yorkshire, South Yorkshire, West Yorkshire and the East Riding of Yorkshire; 13 per cent of total venues, with 30 venues capable of accommodating over 1000 people. Purpose-built venues include the Harrogate International Centre and Conference 21 Sheffield.

Figure 3.10 The North East of England

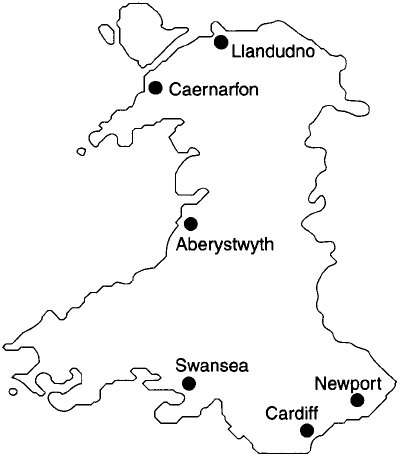

Figure 3.11 Wales

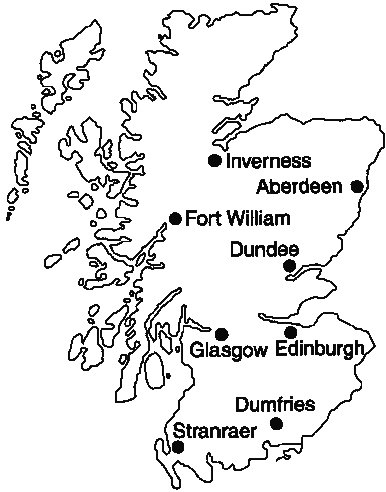

Figure 3.12 Scotland

Wales (Figure 3.11)

Wales has 4.5 per cent of total venues, with nine venues capable of accommodating over 1000 people. Purpose-built venues include the Cardiff International Arena and the North Wales Conference Centre, Llandudno.

Scotland (Figure 3.12)

Scotland has 11 per cent of total venues, with 24 venues capable of accommodating over 1000 people. Purpose-built venues include the Aberdeen Exhibition and Conference Centre, the Edinburgh Conference Centre, the Edinburgh International Conference Centre and the Scottish Exhibition and Conference Centre, Glasgow.

Northern Ireland (Figure 3.13)

Northern Ireland has 2 per cent of total venues, with six venues capable of accommodating over 1000 people. Purpose-built venues include the Belfast Waterfront Hall. The King’s Hall is one of the major large-scale centres.

Ireland (Figure 3.13)

The proportion of venues in the foregoing analysis has excluded Ireland, but Figure 3.13 illustrates the major locations in the republic. Ireland has a number of venues capable of accommodating over 1000 people. In Dublin this includes the National Concert Hall, the Point Theatre, the Burlington Hotel, the Royal Dublin Society (‘RDS’) and University College, Dublin. Other large-scale venues can be found in Athlone, Bundoran, Cork, Ennis, Galway, Killarney, Letterkenny, Limerick, Tivoli, Tralee and Waterford.

Figure 3.13 Northern Ireland and Ireland

Summary

This chapter has considered the various types of conference venue to be found within the United Kingdom and Ireland. While we may typically think of conference centres as being large purpose-built operations, most are not; the largest single component sector is, in fact, hotels. Venues are available in a large geographic spread, but certain areas lend themselves to the provision of conference venues, typically due to their location and accessibility to the market; hence concentrations around London and Birmingham in the UK and Dublin in Ireland.

References

Coopers and Lybrand Deloitte (1990) UK Conference Market Survey 1990, London, Coopers and Lybrand Deloitte Tourism & Leisure Consultancy Service, pp. 1–22.

Dome (1994) An adventure into the world of leisure, Doncaster, Doncaster Leisure Management Ltd (unpublished).

Expotel (1993 The Expotel and Conference Centre Insiders Guide to Conference Planning, London, Expotel.

Fenich, G.G. (1995) Convention Centre Operations: Some questions answered. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 14(3/4), pp. 311–324.

Keynote (1994) Key Note Report, a Market Sector Overview. Exhibitions and Conferences, London, Keynote, pp. 5–9.

Law, CM. (1993) Urban Tourism, London, Mansell, pp. 55–61.

Lundberg, D.E. (1994) The Hotel and Restaurant Business, New York, Van Nostrand Reinhold, pp. 72–89.

Miller Freeman (1996) The Conference Blue Book 1996 (General Venues). Tonbridge, Miller Freeman Technical Ltd.

Miller Freeman (1996) The Conference Green Book 1996 (Special Interest Venues). Tonbridge, Miller Freeman Technical Ltd.

Montgomery, R.S. and Strick, S.K. (1995) Meetings, Conventions and Expositions, New York, Van Nostrand Reinhold, pp. 9–15.

National Exhibition Centre, (1996) Information Pack for the International Conference Centre. Birmingham, Birmingham, NEC Ltd (Unpublished), pp. 1–8.

Savills Commercial (1994) Property - Finance and Investment 5/95, London, Savills Commercial Research, pp. 2–4.