6_______________________________________________________

The provision of food and

drink_______________________________________________________

The aims of this chapter are:

- 1 To explain the chief means by which conference venues organize the catering of events.

- 2 To understand the information required by caterers to provide conference delegates with appropriate meals and service.

- 3 To discuss the types of service on offer to conference delegates in terms of refreshment breaks and drinks services.

6.1 Introduction

Having provided a suitably laid out meeting room for delegates, the issue which will probably most colour their view of the conference itself, if not the venue, is the provision of food and drink. This chapter will look at some of the practicalities of catering for conferences. Refreshment breaks not only provide opportunities for delegates to deal with their personal needs, make phone calls, check out baggage and so on, but are also the chief mechanism by which conference delegates network and socialize. Refreshment breaks and meals are significant factors in determining the quality of the venue and delegates’ perception of it, and a major issue in ensuring repeat business (Kotas and Jayawardena, 1994).

The organization of catering varies considerably depending on the type of venue, but, as a generality, there is a fairly clear split between in-house catering as practised by the conference and banqueting departments of hotel venues and contracted-out catering as practised by other types of venue, ranging from purpose-built conference centres to management training centres. There are advantages and disadvantages to both methods of organization, and the type provided by venues to handle their catering may have as much to do with historical precedent in that venue as with matters of profitability, flexibility and convenience which are the normal issues at hand in the debate about in-house versus contracted-out provision.

Having found a caterer, of whatever type, the basic questions and the starting points to determine what the delegate will have are the same. These are questions of the number of people, of refreshment times, of the budget and of the delegates themselves. It could be argued that one of the chief failings of catering provision at conferences is an insensitivity towards the type of delegates a conference may bring. There is a tendency towards standardized menus which, while convenient for chefs and conference sales co-ordinators, may be inappropriate for certain delegates. Increasingly, delegates are better educated in food and drink than at any time in the past, an issue which was well illustrated during the UK beef crisis of 1996, where some slow-moving conference venues were still pushing out standard menus with beef dishes to conference organizers who were rejecting them with hard words.

The range of services on offer is essentially built around five main refreshment opportunities: breakfast, morning coffee, lunch, afternoon tea and dinner. These are not the only opportunities. It is possible to offer conference delegates working breakfasts, brunches and, in the North of England, especially in Lancashire and Yorkshire, high teas as alternatives, depending on the time structure of a conference. In terms of drinks service, a typical non-residential conference may only extend to a glass of wine or orange juice with the buffet lunch; but for residential conferences, and in particular those that may feature a gala dinner (see Figure 6.1 for an example), there is clearly an opportunity to encourage drink sales at the pre-dinner reception and after dinner for residents, most often through the provision of a cash bar.

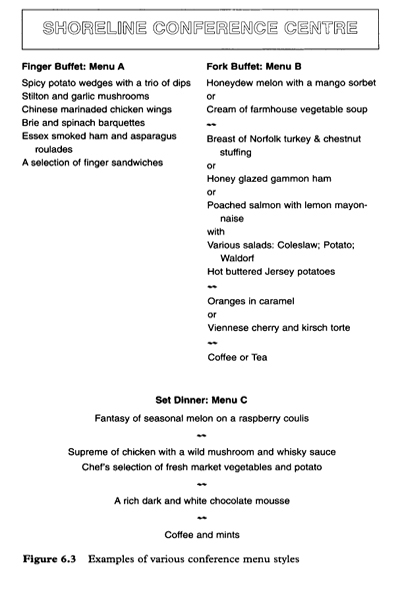

The final key issue regarding meals, in particular, is that of menu composition. This is significant not only in terms of the design of standard menus (see Figure 6.3 for an example), but also where a conference venue may offer a variation of the a la carte system, that is to say a range of individually priced dishes which are suggested to the conference organizer who then chooses a set menu for delegates from the available dishes (see Figure 6.4 for an example). This is based on the view that conference organizers know something of the style, likes and dislikes of the delegates. However, not all do, and organizers often pick dishes they themselves like, only to find that delegates criticize their poor judgement. Menu composition is, therefore, not simply a technical issue, but also one of the most appropriate questions that conference organizers can ask themselves, i.e. what are their delegates’ food preferences?

Gala Dinner Menu

Annual Conference of East Anglian Windsurfers

Cream of courgette and green peppercorn soup

Creme potage de courgette et grains de poivre vert

or

Broccoli and prawns in oyster sauce

Brocoli et crevettes roses sauce huitre

![]()

Baked breast of duck served with raspberry sauce

Supreme de canard foure et sauce framboises

or

Poached fillet of salmon served with drambuie and lobster sauce

filet de saumon poche servir un sauce de drambuie et homard

or

Spicy potato roulade with salad Raita

Roulade de pommes Bombay et salad de concombre, yogurt et menthe

Served with a selection of potatoes and fresh vegetables

Tous accompagne de pommes et legumes fraiche

![]()

Chocolate and malt whisky parfait

Parfait de chocolat Glenlivet

or

A light lemon sorbet

Sorbet au citron

![]()

Coffee and marzipan bites

Cafe avec petits fours

Guest of honour: Andrew Morton-Gray

National President of the Windsurfers Association

12th May 1997

Figure 6.1 Example of a conference gala dinner menu (delegates choose prior to dinner)

6.2 Food and drink organization

There are two main methods of provision in terms of food and drink at conference venues: in-house and contracted (or ‘outsourced’). In-house provision is done by the organization itself as part of its core operation. This is chiefly how hotels operate (Medlik, 1995). The banqueting department of a hotel provides food and drink for all the functions and events that take place within the establishment.

Each organization is different, but the chief’back of house’ players are the Head Chef and the Bars Manager, in the sense that they are responsible for food and drink costings, pre-planning, ordering and preparation of food and drink. Nevertheless, it must be remembered that the initial enquiry and first meeting between the venue and the conference organizer will probably take place with the venue sales manager or conference sales co-ordinator, though a number of conference organizers will ask for the chef to be present.

The alternative is to contract out the catering to a specialist organization (Warner, 1989). Such organizations vary from the large national operations with many contracts to small individual caterers with only one contract. Outsourced catering of this kind is common in purpose-built conference venues, municipal venues, some educational establishments and some specialist venues. Contractual arrangements vary. Some venues may have one approved caterer who provides all the food, drink and related services for that venue. Such contracts are often time limited, e.g. five years. Alternatively, some venues may have an ‘approved’ list of caterers with whom they are happy to work, the caterers being familiar with the venue, its operation and management and typical requirements. A very few venues, such as public halls, may allow any caterer, but this is uncommon.

The advantage of contracting-out is that the venue does not need to concern itself with the technicalities of food and drink provision; it simply makes the best contractual arrangement possible, sometimes on a commission basis, and merely acts as a link between the conference organizer and the caterers. The disadvantage is loss of control: in a contract which lasts five years, a contract caterer interested in cutting costs may have no incentive to provide a quality service, only providing it towards the end of the contract on the basis that the venue management may have a short memory and will happily renew the contract for a further five years. The related disadvantage in terms of ‘loss of control’ is less well known, but probably more serious - loss of flexibility. The in-house catering function is, in practice, highly flexible and can provide peripheral activities which contractors do not. The chief problem is that contracts are often badly written, ignoring a wide range of needs, some of which may only occur occasionally but are nevertheless vital, and for which a contractor will charge extra.

6.3 Basic issues in the provision of food and drink

The starting point for the provision of food and drink is the nature of the conference itself. Clearly a residential conference will require a greater food and drink input than a non-residential conference; similarly a VIP conference will require a greater level of input and service than, say, an association or charity conference might. There are several key questions for the caterer which will determine the arrangements for food and drink - see Figure 6.2.

The number of delegates attending and expected to eat may not be the same, particularly for residential breakfasts or conference dinners. It is also of some importance to have approximate numbers (give or take 10 per cent) up to two weeks prior to the event and final numbers two days in advance to enable not only accurate food and drink ordering but also satisfactory table lay-ups. Last-minute number checks for refreshments can be made as the conference is taking place. The time of refreshment breaks should also be checked with the organizers on the day, as the originally scheduled time may vary depending on circumstances (Seekings, 1996).

• The number of delegates attending and expected to eat

• The times of refreshment breaks and meals

• Details about the delegates themselves:

- Who they are

- Typical interests

- Age group

- Male/female balance

- Special dietary needs (e.9. vegetarians)

• The budget for refreshments

• The expertise and ability of the catering staff

Figure 6.2 Issues in determining menus and refreshments

The budget for refreshments is generally pre-determined from the beginning. It is common for conference organizers to choose from a range of pre-priced set menus or from a list of possible dishes from which an appropriate menu can be made up and costed (see Figure 6.4). If the clients wish to have a special meal prepared for the ‘end of conference’ dinner, the planning of such a meal should take into account the background of the delegates (a conference of medical practitioners may not appreciate a high cholesterol meal) and their interests - are the delegates, for example, outdoor activity enthusiasts and if so how would this impinge on the menu composition? Other issues are the age group of the delegates: younger people may, for example, be particularly averse to red meat dishes, more so than an older age group. What is the balance of male to female delegates? What proportion are likely to be vegetarian? (This latter is an increasingly serious issue, many conference delegates who are not themselves vegetarian may be quite happy to take the vegetarian dish rather than the main dish on offer (Davis and Stone, 1991).

For many years, the food on offer at conference dinners and formal banquets was extremely predictable. A standard fare of prawn cocktail, chicken in sauce and sherry trifle was almost inevitable. Even today, it would be possible for delegates to find common ‘set meals’ including an indeterminate pate, a badly cooked rack of lamb (a recent trend, and bearing in mind the incidence of food poisoning, a deplorable one) and a sweet comprising a brandy snap basket with ice cream on a pool of red berry juice. Conference delegates may be conservative (i.e. traditional) in their tastes, but they are no longer uneducated in food. Travel abroad, ethnic restaurants at home and wide-ranging food programmes and articles in the media have engendered a far greater range of tastes in the UK and Irish public. Conference venues and hotels are not always in the forefront of change when developing menus, nor perhaps would delegates necessarily wish them to be; but it is entirely necessary that the food presented at conferences is of a high standard. Frequently it is not, and part of the reason for this is the lack of competitor analysis (what in other industries would be called benchmarking), and complacency on the part of venues. Older banqueting managers may recall the days when it was de rigueur to go out and eat in competitor establishments, hotels particularly. This is now extremely rare among modern managers and the quality of conference food sometimes suffers from the lack of knowledge of what competitors are providing (Venison, 1983). There are other common weaknesses in conference dining, some of which are training related. Conference dining often relies on casual waiting staff and this is a particular difficulty. Such staff have often gleaned their meagre knowledge of service from other staff or from ad hoc demonstrations by the head waiter or waitress. The days of finding one’s entire banqueting staff consuming the remains of the conference’s sherry trifle in the back room of the banqueting kitchen are not yet gone. Would that such concerted effort went into training or even that it were applied to a half-hour briefing before service about the food, the drink, whom to serve first and how to look around for delegates and diners trying to attract staff attention.

Figure 6.3 Examples of various conference menu styles

Starters: A choice from:

OAK SMOKED SALMON WITH DILL SAUCE

MISCELLANY OF SEAFOOD ON SHREDDED LETTUCE TOPPED WITH A LEMON DRESSING

CHEF’S SMOOTH CHICKEN LIVER PATE

TERRINE OF PORK AND APPLE

FANNED HONEYDEW MELON ON A PASSION FRUIT COULIS

MELON PEARLS, FLAVOURED WITH PORT

HOT MUSHROOM TART WITH A FRENCH MUSTARD GLAZE

FRUITS OF THE FOREST SORBET

COLCHESTER OYSTERS WITH BROWN BREAD

Soups: A choice from:

CREAM OF LEEK AND POTATO SOUP

CREAM SOLFERINO

FRENCH ONION SOUP WITH PARMESAN CHEESE GALETTES

CREAM OF CROMER CRAB SOUP

Main Courses: A choice from:

PAUPIETTE OF SOLE WITH PRAWNS AND LOBSTER SAUCE

POACHED DEUCE OF SALMON IN A WHITE WINE BOUILLON

POACHED SUPREME OF CHICKEN WITH A WHITE WINE AND MUSHROOM SAUCE

ROAST LEG OF LAMB GLAZED WITH A REDCURRANT JUS

INDIVIDUAL BEEF WELLINGTON WITH MADEIRA SAUCE

ESCALOPE OF PORK WITH A LEMON AND ORANGE GLAZE

SUPREME OF PHEASANT WITH STILTON AND PORT SAUCE

OSTRICH STEAK WITH A CREAM, BRANDY AND PEPPERCORN SAUCE

VEGETARIAN MUSHROOM STROGANOFF WITH WILD RICE

VEGETARIAN BAKED STUFFED RED PEPPER WITH ONION GRAVY

ALL SERVED WITH FRESH GARDEN VEGETABLES AND POTATOES

Sweets: A choice from:

A RICH CHOCOLATE AND MALT WHISKY PARFAIT

APPLE AND FRANGIPANE TART WITH VANILLA SAUCE

RASPBERRIES IN COINTREAU FLAVOURED CREAM, WITH LIGHT SPONGE FINGERS

OLD ENGLISH WINTER SPOTTED DICK WITH CUSTARD SAUCE

SHORTBREAD FILLED WITH A STRAWBERRY AND GRAND MARNIER CREAM

A LIGHT CITRUS SORBET

SHORELINES SPECIAL FRESH FRUIT SALAD IN SPRING WATER SYRUP WITH CALVADOS

Cheeses:

SELECTION OF ENGLISH CHEESES

SELECTION OF CONTINENTAL CHEESES

Coffees:

COFFEE WITH CREAM AND MINT CHOCOLATES

COFFEE WITH CREAM AND BELGIAN TRUFFLES

A SELECTION OF FINE TEAS CAN ALSO BE PROVIDED

Figure 6.4 Example of a conference menu suggestion list - the final menu may be selected from a range

The final issue is the feeding of staff and crew. In the effort to cut costs, the feeding of staff is generally neglected, but nevertheless should be a charge supported as part of the total, either calculated into menu prices or added as a specific budgeting line. How many staff and crew need to be fed, with what, at what time and by whom? Will the staff dining room be open, if there is one? Do staff and crew pay for reasonable refreshments in such a dining room? If not, where and how are the staff and crew to be fed?

6.4 Food and drink services

The simplest form of conference will, at some point, involve the consumption of food and drink. A day conference may typically take the format shown in Figure 6.5. For a residential conference, two other meal opportunities can be added: breakfast and the conference dinner. There are, of course, many variations on this type of schedule, depending on the nature of the meeting, its purpose, the delegates, even the location. The day may start earlier with a working breakfast and end with lunch. Certain types of service are common at conferences, however: breakfast is generally a buffet breakfast with both hot and cold dishes, and delegates may therefore choose for themselves whether to have a full cooked breakfast or go for something more continental. In hotels it will also be highly likely that delegates will take breakfast (unless it is a working breakfast) with all the other hotel guests.

Figure 6.5 Example refreshment schedule of a day conference

‘Morning coffee’ is shorthand for ‘morning coffee or tea’, usually with biscuits or small cakes such as miniature Danish pastries. Conference venues must not make the mistake of believing that ‘morning coffee’ refers to coffee only; this is a regrettably common mistake, but a stupid one.

Lunch for conference delegates often has two major prerequisites: first, that it should be relatively light, normally a main course and a sweet; secondly, that it should be brief - to be accomplished in an hour. There are two common types of service - served lunch or buffet lunch. The latter is far more common and itself may be subdivided into two types: finger buffet or fork buffet. With the former, delegates would normally stand, with the latter (again the more common), delegates would normally sit - the buffet food may be hot or cold or both. The timing issue is an important one. The British and the Irish will politely queue at a buffet, but this will increase the time and must be taken into account when laying a buffet. More than one direction or side of a buffet table should be available. It will take the average delegate 20 seconds to load his/her plate - multiply that up by the number of delegates and you will understand why more than one buffet flow is needed for a large event. It should also be borne in mind that buffets are often understaffed. This leads to chaos, inability to restock, inability to clear tables and loss of that conference’s repeat business. The normal buffet service ratio is one staff to 30 diners. This can be raised to 35 if serving international delegates: they are less likely to queue, and will simply descend on a buffet table and ravage it. This must be noted when laying out the buffet - for international delegates the buffet should not generally be laid out in a linear fashion (Cotterell, 1994).

‘Afternoon tea’ is shorthand for ‘afternoon tea or coffee’, usually with biscuits, shortcake, small cakes or scones with jam and clotted cream (depending on the region or locality). Timing is an issue, both at morning coffee and afternoon tea, as sessions may overrun; but, if booked at, say, 3.30 p.m. then the service must be ready at 3.30 p.m. The day this fails to happen is the day the conference breaks on time and thus the ‘missing’ service causes unnecessary friction between the conference organizer and the floor manager or staff on duty.

Conference dinners are often intended as the highlight of the event, sometimes in the form of gala dinners or theme dinners to provide a fitting end (Goldblatt, 1990). Regrettably, they are, as often, badly done, with poorly cooked food, indifferent service and poorly presented staff. Service is not a matter of slapping a plate of chicken in front of a delegate and standing back. It is as important in this environment as it is in the fine restaurants of great hotels. Dinner is typically a seated event, with a preset menu, generally with little or no choice, except for a gala or special dinner; for smaller conference parties, dinner, particularly in hotels, may be taken from the restaurant menu or from a limited choice table d’hôte menu. However, once numbers exceed 50 or so a preset menu is more likely.

This, in theory, should assist the production of a meal of notably good quality, but often it results in the production of a dismally unimaginative and unappetising meal because the kitchen sees it as routine and simple. For a set menu, the typical service ratio is one staff to between 10 and 15 diners, plus one member of drinks staff (for wine service) to every 30 diners.

Bars at this type of function should be staffed at a ratio of one member of staff to every 75 drinkers (for example, at the pre-dinner reception). These ratios can be subject to some variation; for instance, experience of a particular residential conference may conclude that delegates, on previous visits, have been particularly heavy drinkers, thus requiring a strengthening of the service. The importance of this latter point is that the conference and banqueting manager responsible for food and drink service at a conference dinner (or lunch, or breakfast) must be flexible. It is far too easy to assume that a preset standard will do for all functions; this is an easy approach, but leads to lack of attention to the detail of staffing and potentially serious mistakes such as under- or over-staffing.

Bars at conferences are essentially of two types: paid and cash. Paid bars are those where the conference organizer has arranged for some element of payment for delegates, let us say VIPs to have ‘free’ drinks, because the conference organizer (on behalf of the company or association) is paying. In some cases, conference organizers may specify that delegates may cover their first drink by this method; however, such arrangements must be made clear to delegates and strict monitoring applied. Far better, simply, to serve a pre-deter-mined aperitif (e.g. sherry) than attempt to monitor who is ‘just’ having their first drink. The alternative method is to set a bar limit, which the organizer will pay for, and after which delegates pay for their own. Again, this method has severe limitations and could result in an undignified scrum at the bar to get as many ‘free’ ones as possible before delegates have to pay. It is far easier, and much more common, to have a cash bar. Delegates pay for what they have.

There is also the related issue of drinks served during the meal. The most common method is for organizers to include an allowance of one or two glasses of wine or juice with a meal for delegates; thereafter, delegates may buy their own wine on payment to the sommelier (wine waiter/waitress); similarly with liqueurs, which are usually on a cash basis. Drinks service tends to go on the basis of one bottle of wine (75 cl) to six persons with a common ratio of three to one in favour of white to red. Spirit service is of the order of 28 (25 ml) measures to a bottle. Jugged plain water should always be put on the table before the meal arrives. There is a belief that diners will not drink alcohol if water is put on the tables. This belief is fallacious, and it always results in tables asking for water and service being disrupted to get it. Such disruptions delegates can do without.

Cleaning and clearing are issues much neglected in the servicing of conference rooms and at conference meals, particularly buffets. It is essential that when a conference breaks for refreshment or at any other point, the opportunity is taken for minor rubbish clearing, replenishment of consumables within the conference room (e.g. bottled water, glasses, mints etc.) and tidying of the tables prior to delegates returning. This can be regarded as ‘preventative’ action; far better to plan for this to happen as a matter of professional routine than to allow something to go wrong (e.g. the conference runs out of water) and have to expend inordinate effort putting it right. This can be called the ‘egg on the fork’ syndrome. If a restaurant is badly prepared and not checked, then there are things in there waiting to create maximum disruption - the eggy fork will be discovered by a guest, who will demand its replacement at the busiest point of service, causing widespread disruption. Typically there will be no spare forks in the sideboards, so the staff will have to go to the wash-up to get one, a location where, mysteriously, there will also be no spare forks. This will necessitate the slowest washer-up in the entire building having to wash, dry and polish a fresh fork, taking the maximum possible time, while the guest’s food, now cold, will have to be returned to the kitchen. Poor managers and lazy staff may regard good preparation as a nuisance, but it is, in fact, the bedrock on which all else is built. The same is true of clearing and cleaning. Cleaning equipment and materials must be available and accessible to the conferencing support staff. It may not always be a simple case of needing to clear up a broken glass. Delay in responding to these crises, major and minor, is typically due to lack of equipment, material and preparation.

Summary

The thoughtful and well-planned provision of catering services at conferences is essential to the high standard of the delegates’ experience. Venues tend to be traditional in their menu planning, but this may be preferred, of course. Awareness of delegates’ background needs to be shown. Clearly, the catering demands of the Chartered Institute of Accountants will vary considerably from that of the International Society of Epicures.

References

Cotterell, P. (1994) Conferences: An Organiser’s Guide, Sevenoaks, Hodder and Stoughton, pp. 64–83.

Davis, B. and Stone, S. (1991) Food and Beverage Management, Oxford, Butterworth-Heinemann, 2nd edn, pp. 270–300.

Goldblatt, J.J. (1990) Special Events. The Art and Science of Celebration, New York, Van Nostrand Reinhold, pp. 107–117.

Kotas, R. and Jayawardena, C. (1994) Profitable Food and Beverage Management, Sevenoaks, Hodder and Stoughton, pp. 192–235.

Medlik, S. (1995) The Business of Hotels, Oxford, Butterworth-Heinemann, pp. 49–60, pp. 71–84.

Seekings, D. (1996) How to Organise Effective Conferences and Meetings, London, Kogan Page, 6th edn, pp. 94–96, 304–306, 333–335.

Warner, M. (1989) Recreational Foodservice Management, New York, Van Nostrand Reinhold, pp. 11–17.

Venison, P. (1983) Managing Hotels, Oxford, Butterworth-Heinemann, pp. 100–103.