1_______________________________________________________

The evolution and extent of the

conference business___________________________________________

The aims of this chapter are:

- 1 To consider a brief history of trade in Britain and Ireland with specific reference to the conference business and to examine the developments which have resulted in the modern industry.

- 2 To examine the social and economic significance of the conference business.

- 3 To discuss the extent and scope of the conference business in seasonal and geographic terms.

1.1 Introduction

The conference business is a major contributor to the economy in terms of the benefits it brings. These benefits range from the provision of employment to the income from foreign conference delegates visiting both Britain and Ireland. The history of the conference business is chiefly one of great expansion within the past 30 years and to a lesser extent during the previous 250 years, beginning with the creation of assembly rooms in spa towns. Today the industry is a multi-million pound business, but it is not generally perceived as separate, as its fortunes are bound up with that of the hospitality and tourism industry, which provides both in-house conference facilities and also, in hotels, bedroom accommodation for other conference centres.

The impacts on a local community of a major conference centre, be it purpose built, or be it as part of some local hotel provision, can be perceived in terms of the local economic multiplier (Braun and Rungeling, 1992). A conference centre itself may not, for example, provide huge direct employment, but the indirect effects on local businesses, local services and local infrastructure and environment are extremely significant. These indirect effects may include the support of activities such as retailing (conference delegates buying anything from magazines to clothing) and catering (conference delegates using restaurants, coffee shops and pubs outside the main centre) to less obvious support in terms of services such as transport, taxis, advertising, technical equipment supplies and so on.

The conference business is, to some extent, regional, in so far as the biggest concentrations of demand are in London and the Midlands in Britain, and Dublin in Ireland. This demand is facilitated by good transport networks - rail, air and road nets; by the provision of hotels and other forms of accommodation of a high standard; and by the provision of adequate venues themselves. A number of large, purpose-built venues have been opened to cope with this demand, but it is significant to point out that the conference business is highly competitive locally, regionally and nationally.

1.2 History of the conference business

It would be easy to consider the conference business as a ‘recent’ phenomenon in Britain and Ireland, that is to say, a product of the industrial revolution and the need for the greater interchange of ideas. However, this would ignore some 2000 years of recorded civilization, and would wrongly suppose that trade, commercial interaction and debate had not taken place. Trade, interaction and debate did take place and, even on its modest scale, was as important in the basilicas, forums and inns of Roman Britain and the royal raths of Ireland as it is now, in purpose-built conference centres, hotels and inns.

Roman-British society and trade (AD 43–410) was vastly different from those we take for granted today. The evolution of meeting places reflects this. Few people in ancient times travelled far from their birthplace and business was conducted on a smaller and more intimate scale than in our modern world, via a network of personal friends, relatives and acquaintances. In Britain, the centre of activity for business and meeting was the Basilica (public hall) and the Forum (market place). From the first century AD, the cities of Roman Britain all had such places and in the provincial capitals of Cirencester, London, Lincoln and York, these were of considerable importance. Merchants displayed their goods, information and news were exchanged and visitors introduced by local people. In as much as this was true of the provincial capitals, it was also true of the other great cities and towns. From Carlisle in the north to Exeter in the south, from Chester in the west to Colchester in the east, all possessed such buildings, though trade and exchange also took place in taverns and temples. Roman civilization in Britain did not end abruptly, as it had in other parts of the Roman empire after 410, but endured a long slow decline. In some cities, such as King Arthur’s Camelot (i.e. Colchester 475–515) and Wroxeter, new buildings, found by archaeological evidence, suggest that urban civilization long endured before succumbing to the more agricultural society of the Saxon period and early middle ages (Morris, 1995a).

Ireland, the Romans did not conquer. Trade existed, however, and this took place on much the same intimate and local scale as it did in the provincial towns of Roman Britain. The great kings of Ireland, from Tuathal onwards, also encouraged trade and the exchange of merchandise. The splendour and peace with which some of the Irish kings reigned, such as Cormac: ‘obsolutely the best king that ever Raigned in Ireland before himselfe’ (218–256), as a chronicler gently recorded him, and later, at the time of King Arthur in Britain, King Mac Erca in Ireland (Morris, 1995b), saw a great expansion in the activities of merchants and traders. However, after Diarmaid and his conflict with Columba, then abbot of Derry, in 560, the power of the high kings weakened and Christianity took a stronger role in Irish society. The Vikings, invading in 795, began to build walled towns, including Dublin, Wexford, Waterford, Cork and Limerick. This development started to create a society not unlike that of the Saxon period in England, and just as Alfred the Great fought the Danes to a standstill in Wessex, so too did the last of the great Irish high kings, Brian Boru, at the Battle of Clontarf in 1014.

Although the society of the early middle ages in Saxon England and Christian Ireland was predominantly rural and feudal, merchants travelled and goods were traded. Trade often took place in churches, which acted as meeting places and community centres. In England during the reign of King Edgar (949–975) Canon 26 forbade drinking in churches - this was not so much a reflection of blasphemy, but a recognition that churches were meeting places and could become rowdy. After the defeat of the last Saxon king (Harold II) at Hastings in 1066, trade continued to evolve slowly with commerce then beginning to centre on market towns. The Normans began their rule in England by constructing huge castles to subdue the Saxon population. They then expanded this policy to Ireland in 1169, though with less success and much conflict.

Merchants and local people met to trade, exchange news and information and convert goods into cash. Market towns gradually became more important and communications between them, i.e. roads, were improved. The Statute of Winchester (1285) required that highways between market towns be enlarged and ‘cleared for 200 yards’ on each side to discourage robbery. Throughout the middle ages market towns remained important. Trade developed and so did the specialization of trading roles - goldsmiths, for example, became bankers. Towns sought to increase their importance by holding fairs and the medieval merchant guilds sought to control trade in their businesses. The City of London had a number of guilds (sometimes called livery companies) with their own guild halls where their members met, often as a ‘court’ to determine issues of trade (Clout, 1991). In other towns, the merchant guilds held great fairs to attract people to the town for trade and meetings. Preston guild fair, held once every 20 years, survives to this day, as do others, such as Nottingham Goose Fair, an annual event.

Guild halls took over the role of churches as trade meeting places. In York, the Guildhall (c. 1370), St Anthony’s Hall, the Merchant Taylor’s Hall and the Merchant Adventurer’s Hall are all surviving examples of this role, though inns continued to sustain informal gatherings, and meetings of merchants and traders. By the late 1500s, during the reign of Elizabeth I, and throughout the 1600s, inns became more important to trade and commerce, and as meeting places. However, from the mid-1650s, coffee houses began to develop as places to exchange news and to trade. By 1688, Lloyds Coffee House had become the meeting place for London’s shippers and marine insurers and much the same was true of other coffee houses, where bankers, lawyers and other professional people began to meet. The same general pattern took place in Ireland, more so in Dublin, where the Georgian period saw an unparalleled spate of building (Bramah, 1972; Doran et al. 1992). Although very different from today’s conference venue, the common feature of meetings in these locations to undertake trade is clear.

Prior to the industrial revolution, the development of fashionable Georgian towns such as Bath, Buxton and Cheltenham provided an impetus for the creation of major public buildings, including assembly rooms. While these were chiefly places of public entertainment, they also provided for the meeting and congregation of the merchant and professional classes (Girouard, 1990). This was also the case with public buildings in the larger cities of the period, such as the Assembly Rooms in York, built in 1736 by the Earl of Burlington, and those in Dublin, built by Dr Mosse in Parnell Square, now the Gate Theatre. In London, rooms for public assembly could be found not only in some of the larger and more obvious locations such as Guildhall, in the coffee houses of the time, and in the exchanges (the Stock Exchange, the Baltic Mercantile and Shipping Exchange etc.) then being built or extended, but also, of course, at the inns. The greater inns of this period had ‘long rooms’ which, given the development of many inns from monastic hostels, were places for a company of people to meet. By the end of the eighteenth century some of these ‘long rooms’ had become both assembly room and ballroom, many being as ornate and glittering as the assembly rooms of the spa towns (Bruning and Paulin, 1982)

For the purpose of the dissemination of knowledge, there were places of assembly in the older universities such as Oxford, Cambridge, Durham, St Andrews and Trinity College, though these were not commonly ‘public’. Rooms could be found for public meeting purposes in some of the scientific societies such as the Royal Society, Royal Geographic Society and the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts (1754) in London and the Royal Irish Academy in Dublin. As the industrial revolution developed in the early 1800s, the need for places to conduct trade and commerce increased. Some of this trade and commerce took place in town halls, many of which continue in use today as venues for conferences and, of course, entertainment. Following the expansion of the Georgian spa towns of the 1700s into the Victorian resorts of the 1800s (Burkart and Medlik, 1981), the concept of the assembly room was often the precursor of the development of buildings such as ‘Winter Gardens’ and ‘Floral Halls’. These buildings, while intended for leisure purposes, were also suitable venues for assembly and a number of them pre-dated the construction of large exhibition halls associated with the need to show off Victorian engineering skills. The most famous of these latter is probably Crystal Palace, built to house the Great Exhibition of 1851 and later destroyed by fire (1936), a similar fate having overtaken the Bingley Hall in Birmingham. Exhibitions were not the sole reason behind the creation of large halls. There was a growing demand by the middle of the Victorian period for venues for meetings, which was satisfied by the creation of a number of specialist assembly and banqueting locations such as the Cafe Royal and the Connaught Rooms in London and the Shelboume Hotel in Dublin.

Then, as now, however, most meetings were rather small affairs and many were handled by the inns and hotels of the day. Throughout the nineteenth century the principal hotels tended to be run by the railway companies, though with a few masters of the industry, of whom Frederick Gordon was the greatest, running their own companies (Taylor, 1977). Just about anything with the title ‘Grand’ or ‘Metropole’ would serve to denote a major Victorian hotel, examples being the Midland Grand at St Pancras and in Manchester, and others such as those in Brighton, Birmingham, Scarborough, Leicester or Clacton (Shaw and Williams, 1997). Indeed, any Victorian town worth its salt could boast a ‘Grand’ hotel. In so far as such hotels provided accommodation, food and drink to travellers, they also provided rooms for assembly or ‘congress’, as the Victorians would have called it, ranging from small meeting rooms to the vast and opulent ballrooms of the day.

After 1900, however, it was possible to see a change in the demand for meetings. Though assemblies and congresses continued to be driven by trade and industry, there was a slow and gradual increase in activity which, rather than promoting products, or reporting a company’s annual progress, looked to developing staff and sales. The precursors of the sales training meeting, the ‘congress of commercials’ (or commercial travellers) of the 1920s and 1930s, began to develop into something more modern and more recognizable. The beginnings of other types of conference activity were also discernible: with improvements in transport, and particularly the beginnings of commercial air travel between the two world wars, there was a perceptible, though initially small, development of the international conference. The conference trade itself continued to expand after each world war, though more slowly in Ireland, preoccupied by independence after 1921, but in particular from 1945 onwards. By the 1960s, the conference trade was recognizable as a significant part of the turnover of hotels and a number of public venues.

As had been the case with the railway companies during the Victorian period, airline companies such as Pan American and Trans World Airways sought to develop hotels, being concerned that the growth in air transport provision might outstrip the hotel supply. This, together with, in Britain, the Hotel Development Incentive Scheme of 1969, saw a rapid expansion in hotel provision (and thus meeting room provision). Related to the growth of international air travel, there was a concomitant decline in holiday taking in domestic resorts; this pushed a number of the major resorts into considering how to ensure their economic stability and resulted in the opening of the first major purpose-built civic conference venues in the UK, good examples being those in Brighton (1977), Harrogate (1982) and Bournemouth (1984). The development of major civic venues continued sporadically throughout the 1970s and 1980s culminating in the construction of several very large purpose-built centres in major cities in the UK during the 1990s, including the International Convention Centre (ICC) in Birmingham and the Scottish Exhibition and Conference Centre in Glasgow. In total, there are about 30 major centres of this kind in the UK now, which could be described as the front rank of conference centre development. It is very important to bear in mind, however, that such centres probably account for less than 5 per cent of provision. Total provision can be classified into several groups, of which the largest single group is hotels, accounting for 77 per cent of venues (Coopers and Lybrand Deloitte, 1990). See Chapter 3 for an analysis. The classification of conference venues which we will use can be found in Figure 1.1.

Purpose-built conference centres

Municipal multi-purpose centres

Residential conference centres and in-company facilities

Academic venues

Hotels:

• Deluxe city centre hotels

• Country house hotels

• other hotels

Unusual venues

Figure 1.1 Types of conference centre

Some 2000 years of recorded history have been skimmed in a few short paragraphs. Trade and commerce have continued in many forms during those 2000 years. Meetings held for the purpose of trade have also continued, whether in markets or inns, churches or assembly rooms. Nevertheless, the modern world is vastly different from that of AD 100. Conference centres are largely a modern phenomenon, a product of changes in trade, commerce and communication during the past 30 to 40 years. A Roman Briton of AD 100 or a chamberlain of Cormac’s court would probably easily recognize a market (at least an open air one) were he or she transported by a miracle to today, but the modern conference centre would probably mean less, except as a place of assembly. Nevertheless, the conference business is huge and significant; important in both social and economic terms.

1.3 The social and economic significance

Social significance

Conferencing can be seen as part of business travel, within the framework of the tourism industry. The industry comprises a number of elements, the principal ones being the availability of attractions, the provision of transport, the availability of accommodation, food and drink, and the provision of infrastructure and support services. For a town or city wishing to become a destination for business travellers, or more specifically, conference delegates, these elements must be present. In looking back at the historical development of some of the major conference destinations, it can be seen that all four elements are present. This has been the case particularly for resort and spa towns such as Brighton or Harrogate. A purpose-built conference centre would be constructed as a public (or private) project in much the same way as the assembly rooms of the Georgian period were (Girouard, 1990) and was often intended to build on existing elements such as good transport networks (by road or rail); the availability of good local accommodation (hotels) and places of refreshment (restaurants and cafes); also attractions such as a pleasant location, warm climate or tourist attraction in or near the town. In the case of recent developments, the design provided may be several elements put together as a package (the Birmingham ICC having not only a convention area, but also an adjacent hotel and retail area). Law (1993) clearly develops this discussion in the light of the more general aspects of urban tourism and notes that ‘in some cities up to 40 per cent of those staying overnight in serviced accommodation have come from this type of... tourism’. As a consequence, many towns, cities and resorts have seen the conference business as their economic salvation when other forms of tourism, such as vacation tourism or heritage tourism might not be appropriate to their area. A number of conference centre developments have been undertaken on this economic basis, and while conference centres themselves may not, for example, employ large numbers of people, they nevertheless, in Law’s view, have a wide impact on employment in the vicinity.

This is not to say that the development of a conference centre is the correct solution to the economic problems of any town, city or resort. If a public body, such as a city council, invests in a conference centre it must naturally forego investing in something else, say an industrial or retail development or better local housing. There is an opportunity cost. In considering the possibilities for the economic regeneration of an area, the construction of a conference centre is only one option, not a panacea. Loftman and Nevin (1992) clearly make this point in relation to the ICC in Birmingham. The opportunity cost was that of employment foregone because of the need to finance the debt incurred on the capital cost of the development. As they might say in Birmingham - you pay your money and you take your choice. (After a careful financial feasibility study, of course.)

Economic significance

A major comprehensive survey of the UK conference market published by Coopers and Lybrand Deloitte (1990) suggested that the market was worth ‘considerably in excess of £6 billion’ and reported over 115 million delegate days. It is impossible to provide an accurate update of the figures without further research data, and satisfactory comprehensive research has not been carried out since, though a number of other surveys do exist, including the ‘1996 Key Note Exhibitions and Conferences Market Sector Overview Report’ and the annual surveys of the Meetings Industry Association. Unfortunately, none of these surveys appear comparable, and this is an issue which needs to be addressed by the industry and research bodies. In attempting an estimate of the current extent of the market, data from the BDO UK Hotel Industry reports has been analysed (see Appendix 1) to give a notional estimate of changes in the order of magnitude of the business. This is in no way to be taken as the genuine extent, merely as an indication of change. Using this data, which suggested a 9.73 per cent increase during the 1989–1995 period, it is estimated that by 1995 the market in Britain could have been worth £7.1 billion, representing 126.2 million delegate days. In terms of economic significance to the UK, the International Passenger Survey suggests that some £742 million is due to overseas business travellers attending UK conference, meeting and exhibition venues. As a generality, Elliott (1996) noted that every visitor to Britain spends an average of £500, and that every ‘extra planeload adds seven extra jobs’. These figures give some indication, at least, of the importance both of business travel in general and also of conferencing in particular.

It is extremely difficult to quantify the concurrent figure for Ireland, due to a lack of reliable research data. However, the nature of the Irish economy, the importance of the role of tourism and the current extent of conference provision, together with the rural nature of much of Ireland and a limited number of large centres of population, might suggest a region comparable to that of the South West of England, and therefore a notional 9.5 million delegate days or a market worth somewhat about 500 million pounds to the Irish economy, and accounting for some, at least, of the 3.8 million visitors to Ireland (Nevin, 1995).

In the context of a community, the provision of a conference venue, be that venue purpose-built or be it a hotel or similar establishment, is often perceived as having a positive social and economic impact, in much the same way as the construction of a factory or tourist attraction would. The economic impact of hotels, (as conference venues) for example, on local communities is not as well documented (except in so far as local authorities are required to include hotel development analysis in their local structure planning) or researched as the large purpose-built venues. In the case of the latter, it is significant to bear in mind that the construction of purpose-built venues is often a matter of civic business, that is to say the development may be sponsored by the city or town council and based, partly at least, on the economic and social benefits that the development would bring to the community (Braun and Rungeling, 1992; Fenich, 1992). Given the size and extent of the conference market, economic and social benefits may be very great (Law, 1993). Figure 1.2 provides an example.

Clearly, this is development on a grand scale, but similar effects in terms of investment, employment, improvements to the environment and as a catalyst to other projects would be evident in the smaller civic-promoted conference centres around the country. This is not to say that such developments are without criticism; the Birmingham Evening Mail reported a £7.2 million loss on ICC operations in 1994, but noted that, taken as a whole, the ICC and its associated venues were putting £438 million into the West Midlands economy, and since 1994 are making a profit.

In the case of the development of the International Convention Centre in Birmingham, it was felt that the Centre would result in:

• Provision of a ‘world class’ conference venue for the city.

• Regional investment of up to £40 million per annum.

• The security of up to 10 000 jobs indirectly, as well as the provision of 600 during the peak construction period and 2000 when linked to the city centre development.

• Related development of £1.6 billion.

• Complete redevelopment of the immediate area.

• The construction of two new hotels with a total of 464 rooms.

• ‘Priming for an adjacent retail development.’

• Redevelopment and refurbishment of the area, in particular of a number of listed buildings and canalside projects.

Source: National Exhibition Centre Group, 1996; Law, 1993.

Figure 1.2 Economic benefits of conference centre development

1.4 Extent and scope of the conference business

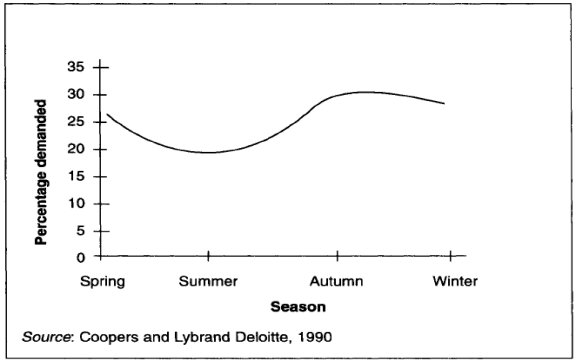

The conference business is partly seasonal in nature, the peak period being September, October and November, the quietest period being the summer. This pattern of demand makes conferencing a particularly attractive activity in locations and establishments that rely, to a greater or lesser extent, on the summer tourist, as the two patterns of demand are complementary. In the earlier consideration of the economic and social benefits of conferencing, this seasonality throws into greater clarity the reasons why resort locations, in particular, have a considerable interest in developing their conference business (see Figure 1.3). Even in areas such as Cumbria, which have no major purpose-built centres, it is still possible to attempt to stimulate demand for conferences via promotional efforts by the Tourist Board or hotel consortia, geared to local hotels, as the conference business will help fill these hotels outside the peak tourist months.

Figure 1.3 Seasonality of the conference business

Although the seasonality of the conference business has benefits in terms of its complementary nature to vacation tourism, a certain caution should be exercised in seeing conferences as a panacea in those areas where seasonal vacation tourism is relied upon. This is because the conference business is not spread equally in geographical terms. Demand is often driven by sectors which are mainly based in major urban areas. Even voluntary sector organizations may well have a head office, say in London, and regional offices in major centres such as Birmingham, Manchester or Newcastle. Similarly in Ireland, with a head office in Dublin, and regional offices in centres such as Cork, Galway, Sligo or Limerick.

Coopers and Lybrand Deloitte’s survey indicated a very specific geographic bias in the spread of demand of delegate days. This spread, calculated alongside the 1995 forecast of delegate days would give a pattern as found in Table 1.1. In considering the geographic spread, a number of elements can be highlighted. The London area is the largest conference destination in the UK. Not only does London have a very large concentration of demand, including head offices of a significant number of organizations, it has also considerable demand from government bodies and from international organizations. The provision of conference venues is also a major contributor to London’s strength: venues include the Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre, the London Conference Forum, the Brewery Centre, the Cafe Royal, the Wembley Conference and Exhibition Centre etc.; London also has a high proportion of deluxe international hotels providing suitable conference and bedroom accommodation. The Midlands is also extremely significant as a conference destination. In particular, the International Convention Centre in Birmingham, the National Indoor Arena and the National Exhibition Centre, together with major venues in other Midland cities such as Sheffield, Leicester and Nottingham, and a high proportion of business hotels, would indicate the Midlands has every chance of becoming the foremost conference destination in the UK due to easier transport links, as opposed to the increasingly congested capital.

Table 1.1 Approximate delegate days in the UK conference market 1995

| Percentage of UK demand | Notional delegate days | |

| London | 35% | 44.0 million |

| South East | 10.5% | 13.0 million |

| South West | 7.5% | 9.5 million |

| East Anglia | 0.5% | 0.6 million |

| Midlands | 30% | 38.0 million |

| North West | 5% | 6.0 million |

| North East | 3% | 3.8 million |

| Yorkshire | 3% | 3.8 million |

| Wales | 2% | 2.5 million |

| Scotland | 2% | 2.5 million |

| Northern Ireland | 2% | 2.5 million |

Source: Author, based on Coopers and Lybrand Deloitte, 1990.

Of the remaining geographic spread, both the South East and parts of the South West benefit from satisfactory accessibility to London and to mainland Europe, particularly for the south coast resorts such as Brighton, Bournemouth and Torquay, which have large and well-established purpose-built centres with generally good hotel and travel infrastructure. East Anglia, conversely, while easily accessible from London, has no perceptible segment of the market and there are no large purpose-built centres anywhere in the East Anglian region; this, coupled with extremely poor intra-regional communications (except to Colchester and in the south of the region), serves to ensure that East Anglia is generally unattractive in terms of the overall conference destination pattern.

In the remainder of the UK, the pattern of demand for conference destinations is spread fairly equally, albeit with slight ‘hot spots’ in the North East and North West (including Manchester), though both these regions suffer somewhat from lack of adequate venues and sufficient hotel room provision. However, recent efforts by Manchester to reposition itself as a ‘24 hour’ European city may result in development in conferencing and greater investment in facilities and hotels, some evidence of this being the opening of the GMEX Seminar Centre as an addition to the GMEX Exhibition Centre in Manchester in 1996.

It is not sufficient, however, to consider the UK and Ireland as relying on their own internal supply and demand factors. The International Passenger Survey has already noted a demand for conferencing of the order of 800 000 visitors to the UK alone per year. A large proportion of these are from the other parts of the (European) Union. A cause for concern for conference venues in both Britain and Ireland is that as communication networks improve (such as the Channel Tunnel and the proposals for de-regulation of air routes), there will be increased competition from venues in locations including Paris and Brussels. Therefore venues must seek to exploit the potential business to be had in the EU (worth some £90 billion - Coopers and Lybrand Deloitte, 1990) and from other non-domestic markets.

Summary

The history and development of the conference business, in both Britain and Ireland, has been closely related to the expansion of trade and the need for the interchange of ideas. The conference business is, in the contemporary world, significant both in social and economic terms as a contributor to local, regional and national development, a factor highlighted by the construction of flagship conference centres such as the ICC in Birmingham. Nevertheless, some regions have a more mature conference demand than others, and better provision, in a very competitive environment.

References

BDO (1989 et seq.) UK Hotel Industry, London, BDO Consultants.

Bramah, E. (1972) Tea and Coffee, London, Hutchinson, pp. 41–52.

Braun, B.M. and Rungeling, B. (1992) The relative economic impact of convention and tourist visitors on a regional economy. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 11(1), pp. 65–71.

Bruning, T. and Paulin, K. (1982) Historic English Inns, Newton Abbot, David and Charles, pp. 13–70.

Burkart, A.J. and Medlik, S. (1981) Tourism: Past, Present and Future, London, Heinemann, pp. 3–37.

Clout, H. (1991) The Times London History Atlas, London, Harper Collins, pp. 62–63.

Coopers and Lybrand (1990) UK Conference Market Survey 1990, London, Coopers and Deloitte Lybrand Deloitte Tourism and Leisure Consultancy Services, pp. 1–22.

Doran, S., Greenwood, M. and Hawkins, H. (1992) Ireland: The Rough Guide, London, Harrap - Columbus, pp. 529–542, 549–551.

Ellingham, M. (1994) England: The Rough Guide, London, Penguin, pp. 601–622.

Elliott, H. (1996) Britons say no to holidays at home. The Times, 3 October, p. 34.

Elliot, H. (1996) Britain is swinging again for young tourists. The Times, 3 October, p. 41.

Fenich, G.G (1992) Convention Centre Development: Pros, Cons and unanswered questions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 11(3), pp. 183–196.

Girouard, M. (1990) The English Town, New Haven USA, Yale University Press, pp. 127–144, 289–313.

Greene, M. (1988) The Development of Management Techniques. In Tourism a portrait, (Horwath and Horwarth, eds), London, Horwath and Horwarth, pp. 21–26.

Law, CM. (1993) Urban Tourism, London, Mansell, p. 39.

Liftman, P. and Nevin, B. (1992) Urban regeneration and social equity, a case study of Birmingham 1986–1992, Birmingham, University of Central England, Faculty of the Built Environment, Research Paper 38.

Morris, J. (1995) The Age of Arthur, London, Phoenix, (a) pp. 136–141, (b) pp. 151–163.

Murray, M. (1995) When will the balloon burst for convention centres? Hospitality, February/March, pp. 16–18.

National Exhibition Centre Group (1996) Information Pack for the International Conference Centre. Birmingham, Birmingham, NEC Ltd (Unpublished), pp. 1–8.

Nevin, M. (1995) A case study in policy success: the development of the Irish tourism industry since 1985. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 13 March, pp. 363–375.

Shaw, G. and Williams, A. (1997) The Rise and Fall of British Coastal Resorts, London, Mansell, pp. 65–69.

Sunday Business (1996) Booming Overseas Visitors invest £742 million in U.K. Conference and Exhibition Industry. Editorial, Sunday Business Newspaper, London, 1 December, p. 31.

Taylor, D. (1977) Fortune, Fame and Folly, London, IPC, pp. 1–14.