A web page consists of markup—HTML or XHTML

that describes the meaning of the content on the page—and CSS (Cascading

Style Sheets) that tell the browser how the content should be displayed in

browsers and other user agents that need to display it. CSS tells the

browser everything from the layout of the page to the colors of your

headings.

In this chapter, whose format differs to the rest of the book, I’ll

explain the basics of CSS syntax and how to apply CSS to your web pages. If

you’re experienced with CSS, feel free to skip this chapter and start with

the solutions in Chapter 2.

This book is not a CSS tutorial; rather, it’s a collection of problems

and solutions to help you perform tasks in CSS. If you’re unsure as to the

very basics of HTML and CSS, I can recommend the SitePoint title Build

Your Own Website the Right Way Using HTML & CSS (third

edition) by Ian Lloyd as a companion to this book. If you already

have some understanding of HTML and CSS, however, this chapter should serve

as a refresher, and can be used as a reference as we work through the

solutions in the later chapters.

The basic purpose of CSS is to allow the designer to define

style declarations—formatting details

such as fonts, element sizes, and colors—and then apply those styles to

selected portions of HTML pages using selectors:

references to an element or group of elements to which the style is

applied.

Let’s look at a basic example to see how this is done. Consider the

following HTML document:

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <head> <meta charset="utf-8" /> <title>A Simple Page</title> </head> <body> <h1>First Title</h1> <p>A paragraph of interesting content.</p> <h2>Second Title</h2> <p>A paragraph of interesting content.</p> <h2>Third title</h2> <p>A paragraph of interesting content.</p> </body> </html>This document contains three boldfaced headings, which have been created using

h1 and h2 tags. Without CSS styling, the headings will

be rendered using the browser’s internal stylesheet; the h1 heading will be displayed in a large font

size, and the h2 headings will be

smaller than the h1, but larger than

paragraph text. The document that uses these default styles will be

readable, if a little plain. We can use some simple

CSS to change the look of these elements:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8" />

<title>A Simple Page</title>

<style>

h1, h2 {

font-family: "Times New Roman", Times, serif;

color: #3366cc;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<h1>First Title</h1>

<p>A paragraph of interesting content.</p>

<h2>Second Title</h2>

<p>A paragraph of interesting content.</p>

<h2>Third title</h2>

<p>A paragraph of interesting content.</p>

</body>

</html>

All the magic lies between the

style tags in the head of

the document, where we specify that a light blue, sans-serif font should

be applied to all h1 and h2 elements on the page. Regarding the syntax,

I’ll explain it in detail shortly. By changing the style definition at the

top of the page, it’s unnecessary to add to the markup itself; it will

affect all three headings, as well as any other headings that might be

added at a later date.

Note: HTML or XHTML?

Throughout this book, the examples will be presented with HTML5 documents using XML-style syntax, as this is my preference. All these examples, however, will work in an XHTML or HTML4 document.

The simplest method of adding CSS styles to your web pages is to

use inline styles. An inline style is applied to

an HTML element via its style attribute, like this:

<p style="font-family: "Times New Roman", Times, serif; color: #3366cc;"> Amazingly few discotheques provide jukeboxes. </p>An inline style has no selector; the style declarations are applied to the parent element. In the above example, this is the

p tag.

Inline styles have one major disadvantage: it’s impossible to

reuse them. For example, if we wanted to apply the style above to

another p element, we’d have to type

it out again in that element’s style attribute. And if the style needed

changing further on, we’d have to find and edit every HTML tag where the

style was copied. Additionally, because inline styles are located within

the page’s markup, it makes the code difficult to read and

maintain.

Another approach for applying CSS styles to your web pages is to

use the

style element, as in the

first example we looked at. Using this method, you can declare any

number of CSS styles by placing them between the opening and closing

style tags, as follows:

<style> … CSS styles go in here… </style>The

style tags are placed

inside the head element, and while it’s nice and simple, the style tag has one major disadvantage: if you

want to use a particular set of styles throughout your site, you’ll have

to repeat those style definitions within the style element at the top of every one of your

site’s pages.

A more sensible alternative is to place those definitions in a

plain text file, then link your documents to that file. This external

file is referred to as an external stylesheet.

An external stylesheet is a file

(usually given a .css filename) that contains a

website’s CSS styles, keeping them separate from any one web page.

Multiple pages can link to the same .css file, and

any changes you make to the style definitions in that file will affect

all the pages that link to it. This achieves the objective of creating

site-wide style definitions as mentioned previously.

To link a document to an external stylesheet (say,

styles.css), we simply place a link element within

the document’s head element:

The linked styles.css file contains the

following style definition:

<link rel="stylesheet" href="styles.css" />Remember our original example in which three headings shared a single style rule? Let’s save that rule to an external stylesheet with the filename styles.css, and link it to the web page like so:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8" />

<title>A Simple Page</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="styles.css" />

</head>

<body>

<h1>First Title</h1>

<p>A paragraph of interesting content.</p>

<h2>Second Title</h2>

<p>A paragraph of interesting content.</p>

<h2>Third title</h2>

<p>A paragraph of interesting content.</p>

</body>

</html>

The value of the rel

attribute must be stylesheet. The

href attribute indicates the

location and name of the stylesheet file.

Note: Not Your Type

You’ll often see the link to the stylesheet written as:<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css"

href="styles.css" />. We’ve omitted the type attribute here because we’re using

HTML5, which, along with browsers, has no requirement for

it.

h1, h2 {

font-family: "Times New Roman", Times, serif;

color: #3366cc;

}

As with an image file, you can reuse this

styles.css file in any page in which it’s needed.

It will save you from retyping the styles, as well as ensure that your

headings display consistently across the entire site.

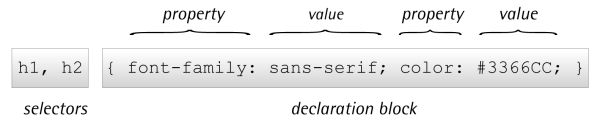

A stylesheet is a collection of style definitions. Every CSS style

definition, or rule, has two main components:

The declaration block contains one or more style declarations and

each one sets the value of a specific property.

Multiple declarations are separated by a semicolon (;). A property

declaration is made up of the property name and a value, separated by a

colon (:). You can see all of these elements labeled in Figure 1.1.

The solutions throughout the book focus mainly on the different

properties and the values they can take. Figure 1.1 also illustrates that a style rule can be

written in a single line. Some CSS authors prefer to indent their style

rules to aid readability, while others write their rules on one line to

save space. The following shows the same style rule written both

ways:

h1, h2 {

font-family: "Times New Roman", Times, serif;

color: #3366cc;

}

h1, h2 {

font-family: "Times New Roman", Times, serif; color: #3366cc;

}

The formatting makes no difference at all; it’s totally up to you

how you write your stylesheet.

A selector is what we use to target the particular bit of markup

on the page that we wish to style. These range from very simple

(targeting a particular HTML element by name) to complex (targeting an

element when it’s in a certain position or state). In the following

example,

h1 and h2 are the selectors, which means that the

rule should apply to all h1 and

h2 elements:

h1, h2 {

font-family: Times, "Times New Roman", serif;

color: #3366CC;

}

We’ll be seeing examples of CSS selectors throughout the book, so

you should quickly become accustomed to the different types of selector

and how they work. Below are some examples of each of the main selector

types, so these should be familiar when you encounter them

later.

The most basic form of selector is a type

selector, which we’ve already seen. By naming a particular

HTML element, you can apply a style rule to every occurrence of that

element in the document. Type selectors are often used to set the basic

styles that appear throughout a website. For example, the following

style rule might be used to set the default

h1 font for a website:

h1 {

font-family: Tahoma, Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif;

font-size: 1.2em;

color: #000000;

}

Here we’ve set the font, size, and color for all h1 elements in the document.

Assigning styles to elements is all well and good, but what

happens if you want to assign different styles to identical elements

that occur in various places within your document? This is where CSS

classes come in.

Consider the following style, which colors all

h2 headings blue in a document:

h2 {

color: #0000ff;

}

That’s great, but what would happen if you had a sidebar on your

page with a blue background? If the text in the sidebar were to display

blue as well, it would be invisible. What you need to do is define a

class for your sidebar text, then

assign a CSS style to that class.

First, edit your HTML to add a

class to the

heading:

<h2 class="sidebar">This text will be white, as specified by the

CSS style definition below.</h2>

Now write the style for this class:

h2 {

color: #0000ff;

}

.sidebar {

color: #ffffff;

}

This second rule uses a class selector to indicate that the style

should be applied to any element with a class value of .sidebar.

The

period (.) at the beginning indicates

that we’re naming a class instead of an HTML element.

You can add a class to as many elements in your document as you

need to.

In contrast with class selectors, ID

selectors are used to select one particular element, rather

than a group of elements. To use an ID selector, you first add an

id attribute to the

element you wish to style. It’s important that the ID is unique within

the HTML document:

<p id="tagline">This paragraph is uniquely identified by the ID

"tagline".</p>

To reference this element by its ID selector, we precede the ID

with a

hash (#). For example, the following

rule will make the preceding paragraph white:

#tagline {

color: #ffffff;

}

The next group of selectors we shall take a look at are

combinators. The combinator refers to a character

added between two simple selectors to create a selector more capable of

targeting a precise part of the document.

The descendant selector matches an element that descends from a

specified element. The combinator used in this selector is a

whitespace character.

You might have an

h2 element

on your site that’s set to display as blue; however, within the

sidebar of the site are some h2

elements that you want to display white in order to show up against a

dark background. As we saw earlier, you could add a class to all these headings, but it would

be far neater to instead target them with CSS. This is when the

descendant selector is used.

Here’s the new selector:

.sidebar h2 {

color: #ffffff;

}

And here’s the updated HTML:

<div class="sidebar"> <h2>A heading in white</h2> <h2>Another heading in white</h2> </div>As you can see, a descendant selector comprises a list of selectors (separated by spaces) that match a page element (or group of elements) from the outside in. In this case, because our page contains a

div element with a

class of sidebar, the descendant selector

.sidebar

h2

refers to all h2 elements inside

that div.

By using a descendant selector, there’s no need to access your

HTML to add classes directly to all elements; instead, use the main

structural areas of the page—identified by classes or IDs where

required—and style elements within them.

Unlike the descendant selector—which matches all elements that

are descendants of the parent element, including elements that are

not direct descendants—the child selector matches

all elements that are the immediate children of a specified element.

The combinator used in this selector is the

greater-than sign (

>).

Consider the following markup:

<div class="sidebar">

<p>This paragraph will be displayed in white.</p>

<p>So will this one.</p>

<div class="tagline">

<p>If we use a descendant selector, this will be white too.

But if we use a child selector, it will be blue.</p>

</div>

</div>

In this example, the descendant selector we saw in the section called “Descendant Selectors

”, .sidebar p, would

match all the paragraphs that are nested within the div element with the class sidebar, as well

as those inside the div with the

class tagline. But if, instead,

you only wanted to style those paragraphs that were direct descendants

of the sidebar

div, you’d use a child selector. A child

selector uses the > character to specify a

direct descendant.

Here’s the new selector, which sets the text color to white for

those paragraphs directly inside the sidebar

div (but not those within the tagline

div):

p {

color: #0000FF;

}

.sidebar>p {

color: #ffffff;

}

An adjacent selector will only match an element if it’s adjacent

to another specified element. The combinator for this selector is the

plus character (

+).

Therefore, if we have HTML:

<h2>This is a title</h2> <p>This paragraph will be displayed in white.</p> <p>This paragraph will be displayed in black.</p>And then use the following selector:

p {

color: #000000;

}

h2+p {

color: #FFFFFF;

}

Only the first paragraph will be displayed in white. The second

p element is not adjacent to an

h2 element, so its text will be

displayed in the black we’ve specified for p elements in the first rule.

A pseudo-class selector acts as if an element has a class

applied according to the state of that element. Pseudo-class selectors

start with a

colon and are usually added

immediately after a type selector with no additional whitespace.

My aim here is to familiarize you with the syntax of and

terminology around these selectors, so that as we meet them later,

you’ll have an understanding of how they work. As a result, I won’t

demonstrate all the selectors in this chapter, but a full list with

explanations can be found online in the SitePoint CSS

Reference.

Most of us first come across pseudo-class selectors when they’re

applied to links. A link has various states. It can be unvisited or

visited, hovered over, or clicked. We can use CSS to target each of

these states:

a:link {

color: #0000ff;

}

a:visited {

color: #ff00ff;

}

a:hover {

color: #00ccff;

}

a:active {

color: #ff0000;

}

The first definition sets the color for the

link state, which displays for links that users

have visited. If they have visited the link, the second rule is used.

If they hover over the link, the :hover definition

is used, and when clicking or otherwise activating the link, the

:active definition is used. The

:hover and :active pseudo-class

selectors are actually termed dynamic

pseudo-classes, as they take effect only when the user

interacts with the element; something has to happen before they take

effect.

The order of these definitions in your document is important.

The a:active definition needs to come last so that

it overwrites the previous definitions. We’ll find out why that’s the

case later on in this chapter, when we discuss the cascade.

The

first-child pseudo-class selector targets

an element when it’s the first child of a parent element. As with all

these selectors, it’s far easier to understand when you can see an

example.

Within your document is a set of paragraphs. These are contained

inside a div element with a

class of article. We can use CSS and a descendant

selector to address all these paragraphs, making them larger and

bold:

.article p {

font-size: 1.5em;

font-weight: bold;

}

If you’d just like the first paragraph to display in a larger

font size and bold—by way of an introduction to the article—you can

use first-child:

.article p:first-child {

font-size: 1.5em;

font-weight: bold;

}

This CSS is only applied by the browser if the paragraph is the

very first p element inside an

element with a class of article.

So the first-child pseudo-class selector is useful

for adding nice design touches, such as making the first paragraph of

some text—or the first instance of a heading—slightly

different.

Just as we can use

first-child to address the

very first instance of an element inside a container, we can use

last-child to address the last instance. The

following CSS would add a bottom border to each list item in a

list:

.navigation li {

border-bottom: 1px solid #999999;

}

To prevent the border displaying on the last item, you can use

the following CSS:

.navigation li {

border-bottom: 1px solid #999999;

}

.navigation li:last-child {

border-bottom: none;

}

The

nth-child pseudo-class selector lets you

select multiple elements according to their position in the document

tree. The easiest way to see this in action is by taking a common

example of striping table rows to make them easier to read.

The following CSS declaration will give a table cell a

background color only if it’s in an odd row of the table:

tr:nth-child(odd) td {

background-color: #f0e9c5;

}

In addition to odd and even keywords, you can use a multiplier

expression:

tr:nth-child(2n+1) td {

background-color: #f0e9c5;

}

We’ll be looking at nth-child in more depth

later in the book, where I’ll explain how to use these multipliers to

target various parts of a data table.

The

only-child pseudo-class selector will

select an element if it’s the only child of its parent. For example,

if I have in my markup the following two lists—the first having three

list items and the second having one:

<ul> <li>Item one</li> <li>Item two</li> <li>Item three</li> </ul> <ul> <li>A single item list - not really a list at all!</li> </ul>The CSS declaration below would only match the list item in the second list, as it matches where the

li is an only child of the parent ul:

li:only-child {

list-style-type: none;

}

Pseudo-elements operate as if you’ve added new HTML markup

into your page and then styled that markup. In the CSS3 specification,

pseudo-elements are denoted with a

double colon; for example,

p::first-letter.

However, for pseudo-elements that existed in

CSS2 (such as ::first-letter,

::first-line, ::before, and

::after), browser manufacturers are asked to maintain

support for the

single colon syntax that these selectors used in the past.

If you’re utilizing the above selectors, at the time of writing a single

colon has better browser support, so I’d suggest employing this. The

exception is ::selection, which was added in the CSS3

specification.

The

first-letter pseudo-element selector acts

as if you’ve wrapped a span around

the first letter of the content inside your parent element and are

then styling it. For example, if we used a span within the markup we might have:

<div class="wrapper">

<p><span class="firstletter">T</span>his is some text within a div

with a class of wrapper.</p>

</div>

And in the CSS:

.wrapper .firstletter {

font-size: 200%;

font-weight: bold;

}

Or we could remove the span

from the markup and target the first letter in the same way using the

first-letter pseudo-element selector:

.wrapper:first-letter {

font-size: 200%;

font-weight: bold;

}

In the same way

first-letter

selects the first letter within a container, first-line selects the first line:

.wrapper:first-line {

font-size: 200%;

font-weight: bold;

}

The first-line selector is far more flexible

than actually wrapping the first-line of text in a

span and styling that. When wrapping content in a span, it’s not known whether the length of

the first line may change (due to the user’s text size, for example,

or a change in the text added by a content management system). The

first-line pseudo-class selector

will always format the first line of text as displayed in the

browser.

The

before pseudo-element is used along with

the

content property to specify where

generated content should be rendered.

Generated content is content that’s rendered in your

document from CSS. This can be useful for a variety of reasons, which

we’ll look at later in the book. For now, here’s the HTML for a simple

example:

<div class="article"> <p>Hello World!</p> </div>And the CSS:

.article:before {

content: "Start here";

}

When viewed in a browser, this will render the words “Start

here” just inside the opening div

element—that’s before the first p.

The

after pseudo-element works in the same

way as before, but it renders the content at the

end of the parent element; that’s just before the closing div in our aforementioned HTML

example:

.article:after {

content: "End here";

}

Given the same markup used for the previous

before example, the previous CSS would render “End

here” just before the closing div,

after the closing p tag.

Attribute selectors let you target an element based on an

attribute. As an example of an attribute on an HTML element, we can look

at the

a element, which creates a

link. Attributes on the following link are href and title:

<a href="http://google.com" title="Visit Google">Google</a>With an attribute selector, we can check what the value of an attribute is, and show CSS based on it. As a simple example, if we take a

form

input field, it has a type attribute explaining what kind of field

it is. Valid values for the type

attribute include text, radio, and checkbox. If we try and style a checkbox in the same way as a text

input

field, we’ll end up with a very strange result, so we can use an

attribute selector to create a definition only for input fields with a type of text. For example,

here is a form field:

<input type="text" name="name" id="fName" />The CSS to target this field is as follows:

form input[type="text"] {

background-color: #ffffff;

color: #333333;

}

In Chapter 6, we’ll be looking at more

examples of using attribute selectors.

You’re probably already aware that not all browsers are equal in

their support of CSS, and that’s before you take into consideration that

some users may well have old versions of browsers on their desktop. The

examples in this book should all work as described in the current versions

of the main browsers; in fact, most will work on previous versions of

these browsers as well. Where a certain feature is unavailable in older

versions of, say, Internet Explorer, I’ll indicate this fact.

In Chapter 7, I’ll explain a number of

ways to get older browsers up to speed with the latest CSS, such as using

JavaScript to add support for CSS3 selectors in older versions of Internet

Explorer. If you know that a project you’re working on will have a large

share of its users using old versions of IE, for example, it’s advisable

to turn to that chapter to plan your support strategy from the

outset.

As you move through the solutions in the next few

chapters, you’ll see examples of one way that browsers are coping with

the introduction of CSS3. The CSS3 specification is different from

earlier specifications in that it is modular. The spec is broken down

into modules that can each reach completion—in W3C terms this is known

as a W3C Recommendation—at different times. The stages a module moves

through are as follows:

While a module is moving through the various stages, browser

manufacturers often start implementing the module at Working Draft

stage. This is good, because it helps to provide implementation

experience in terms of how the specification works when used; however,

it is possible that implementation details could change from the initial

proposal.

For example, if you had used a CSS3 property that

subsequently changed, a site built a year ago might suddenly look very

odd indeed in a new browser that changed the implementation to the new,

correct way of doing it.

To avoid this issue, browser manufacturers often use a vendor

prefix when doing their early stage implementations to create a

vendor-specific implementation of the property. For example, we use

- Working Draft: the module has been published for review by the community

- Candidate Recommendation: implementation experience is gathered during this phase

- Proposed Recommendation: the module is sent to the W3C Advisory Committee for final endorsement

- W3C Recommendation: the module is now endorsed by the W3C and should be widely adopted

border-radius to create rounded corners like

so:

border-radius: 10px;However, for rounded corners to work in earlier versions of Firefox and Safari, you’d also need to add the vendor-prefixed versions:

-webkit-border-radius: 10px; -moz-border-radius: 10px; border-radius: 10px;Once the module is unlikely to change, the browsers start supporting the real property alongside their own. Some browsers may never have a vendor-specific version and just implement the one from the specification. You’ll witness many examples of these prefixed properties throughout the book, so you should soon become comfortable using them.

So how does the browser understand our intentions? When more than

one rule can be applied to the same element, the browser uses

the cascade to determine which style properties to

apply.

Understanding the cascade is important when dealing with CSS,

because many CSS development problems are due to styles being

unintentionally applied to an element. We’ve already presented examples in

this chapter where we’ve written a general style rule focused on paragraph

elements, and then a more specific rule aimed at one or more particular

paragraphs. Both style rules target paragraphs, but the more

specific rule overrides the general rule in the case of matching

paragraphs.

There are four factors that the browser uses to make the decision:

weight, origin, specificity, and source order.

The weight of a particular style declaration

is determined by the use of the keyword

!important.

When the keyword appears after a property value, that value can’t be

overridden by the same property in another style rule, except in very

specific circumstances. Using !important in your

stylesheets has a huge negative impact on maintainability, and there’s

often little call for it anyway. For these reasons it should be avoided,

which we’ll do in this book. If you’d like to know more, you can read

about it in the SitePoint

CSS Reference.

There are three possible stylesheet origins:

the browser, the author, and the user. In this book, we focus on what are

called author stylesheets; that’s stylesheets

written by the web page creator—you! We’ve mentioned the browser internal

stylesheet that provides the default styles for all elements, but styles

in author stylesheets will always override styles in the browser default

stylesheet. The only other possible origin for stylesheets are user

stylesheets—custom styles written by the browser users—and even these are

overridden by the author stylesheet except in rare circumstances. Again,

if you’d like to know more, the SitePoint CSS Reference has a whole

section on it.

The two parts of the cascade that will affect your daily CSS work

the most are specificity and source order. The rule of

specificity ensures that the style rule with the

most specific selector overrides any others with less-specific

selectors.

To give you an example of how this works, consider this simple

snippet of HTML markup:

<div id="content"> <p class="message"> This is an important message. </p> </div>Now consider the following style rules that are to be applied to this HTML:

p { color: #000000; } .message { color: #CCCCCC; } p.message { color: #0000FF; } #content p.message { color: #FF0000; }These four selectors all match the paragraph element in the example HTML and set the text color. What color will be applied to the paragraph? If you guessed

#FF0000, or red, you’d be right. The

p type selector (any p element) has the lowest level of specificity,

with .message (any element with class

message) coming next. The selector

p.message (any p element with

class

message) then has a higher level of

specificity. The highest is the selector #content

p.message (any p element with class

message that is a child of the element with

id

content).

Longer selectors aren’t necessarily more specific. An ID selector,

for example, will always have a higher specificity than an element

type or class selector. It becomes trickier the more

complex your selectors are, but you should find the examples in this book

simple enough. If you’d like to know the exact formula for measuring

specificity, once again the SitePoint CSS

Reference has all the answers.

If two or more style rules are still applicable to an element, the

order in which the rules appear—the source order—is

used. The last rule to be declared is applied. This is also true if you

declare more than one style rule with the same selector; for example,

.message in your stylesheet. It will be the second

instance of the rule that will be applied to the element. As we’ll see in

later chapters, this behavior is very useful.

Since I wrote the previous edition of this book, the use of CSS

frameworks by designers to speed up the development of their CSS has

grown.

My take on these frameworks is that they can be very useful,

but they’re no substitute for learning CSS. Once you understand CSS and

are used to writing it for your projects, you may come up against workflow

issues that are resolved by employing some of the available tools and

frameworks. If they solve a problem you have—great! There is nothing

inherently wrong with building on the work of other people. However, if

your problem is that you lack a good grasp of CSS, the use of any

framework is more likely to compound your confusion—adding another layer

of complexity that will only make it harder to come to grips with the

basics.

This chapter has given you a taste of CSS and its usage at the basic

level. We’ve even touched on the sometimes confusing concept of the

cascade. If you’re a newbie to CSS but have an understanding of the

concepts discussed in this chapter, you should be able to start using the

examples in this book.

The examples in the early chapters are simpler than those found

later on, so if you’re yet to work with CSS, you might want to begin with

these. They will build on the knowledge you gained in this chapter to

start using and, I hope, enjoying CSS.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.