PREP WORK: GETTING YOUR HOME AND YARD READY

YOU’VE LEARNED THAT you can legally keep chickens in your backyard. Now, before you bring home your chicks or eggs—whether your first or fiftieth set—you need to prepare. Gather all your equipment and keep it nearby in a handy space. Stock the necessary food, water, and vaccines. Do a once-over of your yard and tools to make sure everything’s in good repair before your birds arrive. To really get ahead of the curve, plan for your coop to include water collection; you can accumulate and store rainwater runoff for watering outdoor runs or a nearby garden or to fill coop waterers.

In chapters 5 and 6, we discuss the specifics of chick incubation and brooders, respectively. In chapter 7, we provide details about setting up a coop. This chapter is intended to get your wheels turning in the right direction to make your home chick- and chicken-friendly.

SETTING UP SPACES IN THE HOME

Some of the spaces you’ll need to consider for your birds are as follows:

![]() A place to incubate/hatch eggs

A place to incubate/hatch eggs

![]() The brooder

The brooder

![]() The coop

The coop

![]() A quarantine pen—essential to plan ahead

A quarantine pen—essential to plan ahead

[ Know the ins and outs of a safe and healthy environment for your flock and have a solid plan in place. ]

Incubation/Hatching Area

Hatching chicks at home requires a special area for this activity. If you value your eggs and the chicks they will bear, look critically at all potential spaces. An ideal incubator area is well ventilated but draft-free, a place away from high traffic, and one where you can regulate temperature. A spare bedroom or bathroom, for example, works well. If you worry you might forget about incubation-related duties because the incubator is out of sight, hang reminder notes in high-traffic areas or some place you look frequently, such as your bathroom mirror.

You also need a sturdy table on which to place the incubator. This is especially important if children will likely lean on the table to examine the incubating eggs. Also, within your room of choice, do not place the incubator or the table directly above or below an air vent, which may cause incubator temperatures to fluctuate, or in direct sunlight, which can cook the eggs.

Hatching your chicks in a home setting requires planning ahead to ensure an ideal location with all the necessary equipment and environmental controls.

Brooder Space

Once you have chicks, whether you hatch them at home or buy them, you need a room suitable for setting up a brooder (described further in chapter 6). This should be draft-free and separate from the room where you incubate your eggs (if you are incubating your own). Again, high-traffic areas near doors that lead outside create drafts, so select a spare room, if possible. Because chicks create messes, try to find a room with a linoleum floor for easier cleanup.

As tempting as it may be, it is not a good idea to set up a brooder in a child’s bedroom. Children tend not to have good hand-washing habits, increasing the potential for them to pick up Salmonella or other illnesses from the chickens. (Chickens can also get some organisms from children, too!)

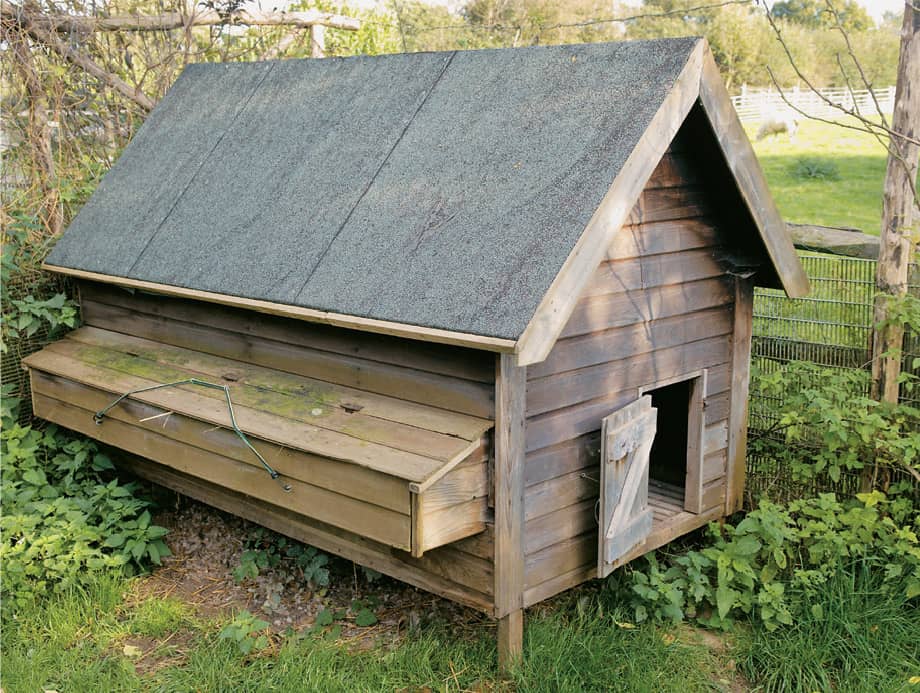

The Coop

Where to put a coop on your property is a personal decision, but here are some tips to help you decide.

![]() Take advantage of trees in your yard for shade during the hottest times of day. This will cut down on coop-cooling costs during hot months.

Take advantage of trees in your yard for shade during the hottest times of day. This will cut down on coop-cooling costs during hot months.

![]() Also, consider carefully when deciding between mobile and stationary coops (we get into this in much more detail in chapter 7). You can move a mobile coop during winter days to parts of the yard that receive extra sunshine.

Also, consider carefully when deciding between mobile and stationary coops (we get into this in much more detail in chapter 7). You can move a mobile coop during winter days to parts of the yard that receive extra sunshine.

![]() If you opt for a stationary coop, locate it near a water source for ease of filling and cleaning waterers.

If you opt for a stationary coop, locate it near a water source for ease of filling and cleaning waterers.

![]() If possible, locate your coop near an electrical source for running a fan during the summer and infrared or electric water-base heaters during the winter.

If possible, locate your coop near an electrical source for running a fan during the summer and infrared or electric water-base heaters during the winter.

Remember to incorporate local zoning requirements. If you live within the limits of a city, there may be an extra layer of complication to this process. Cities each use different language to refer to chickens and the coop (refer to chapter 3 for more about laws). Look at the laws referring to animals and also to accessory structures. Some cities consider a coop an accessory structure much like a shed in your backyard. For the coop, that could mean required distances from a property line or a fence. Height may also be a factor. The bottom line is to do your homework before making a purchase.

A garden chicken run and coop

A shady location is a plus in hotter climates.

Quarantine Pen

Few chicken owners think about a quarantine or sick pen until an emergency arises. This is a place to relocate sick or injured birds as they heal. Think about this pen’s location early, as you prepare for chicks. Where will it sit in relation to the regular coop?

Locate the sick pen as far as physically possible from the regular coop. Is there a far side of your house where no one goes frequently? This could work. Also think about airflow on your property. If possible, situate the quarantine pen downwind from your regular coop in case a flock member picks up an airborne pathogen. You can use something as simple as a dog crate for this pen, as long as it is secure from predators and the elements: something that won’t overheat during the summer or freeze during the winter.

Many people are forced to stick the sick pen in the garage or in another high-traffic area because they did not plan ahead. This is not preferable. The goal of a quarantine pen is to keep the organism residing in the bird far away from the rest of the flock. If you keep your feed, boots, or barn clothing in the garage—in the same place as the sick pen—then you may track the organism right back to the rest of your flock. Find an area with low foot traffic that provides quiet in which the chicken’s body can repair itself, such as the following:

![]() A spare bedroom

A spare bedroom

![]() A side shed near the house

A side shed near the house

![]() A dog kennel nearby

A dog kennel nearby

![]() A nook somewhere near the barn

A nook somewhere near the barn

Plan for all eventualities. Keep separate equipment in the sick area because dirty equipment shared around the farm or yard also can spread disease (see the “Biosecurity” section of chapter 10). Mark equipment designated for the quarantine area with colored tape (such as an eye-catching red). Remember, to keep a flock happy and healthy, you need to plan ahead for potential problems.

A quiet, isolated sick pen is important for the ailing bird as well as her flock members.

PREPARING FAMILY PETS

Before your chickens or chicks come home, consider any family pets already at your residence. Some dogs and cats have strong predatory instincts and may exhibit extremely high prey drive toward your chickens. In other words, they’ll attack anything that looks like prey. If you are unsure whether your pets have this tendency, try a preliminary introduction with training in mind. For example, if you have friends or family with chickens, borrow and bring home a few feathers for the dog or cat to smell. Don’t make a big deal about the feathers. Rather treat them like something completely normal and expected for the pet. If the pet exhibits too much excitement about the feathers, then that is the time for you to correct the behavior. Cultivate the behavior you want in your pets and correct the ones you don’t want.

And once you bring your chickens home, keep cats and dogs away from and out of the coop. Pathogens can hitch a ride on their fur and paws right into your home. Pathogens can also be carried inside your cat or dog. Do not let your pets (chickens, cats, or dogs) share detrimental organisms with one another.

Cats

Cats usually do not like traveling to new places, period, so we don’t recommend bringing them to a farm for a through-the-fence introduction to chickens. Cats tend to pose the greatest risk when you brood chicks inside the home. A housecat may like nothing more than to “play” with your new baby chicks. Obviously, that’s a no-no. Place a window screen over the brooder top to keep kitty out.

Cat curiosity could be injurious to your chicks.

Dogs

Dogs, on the other hand, tend to handle traveling well. Start with an on-farm, through-the-fence introduction to chickens and watch the dog closely. Immediately correct unacceptable behaviors such as excitement, whining, barking, or focused, intense gazes toward the chickens. Make the dog lie down or face away from the chickens until calm. Keep the canine’s attention on you as much as possible. And remember that your level of tenseness and excitement transfers right down the leash to the dog. Act nonchalant but in charge. If you have multiple dogs, conduct separate introductions so the behavior of one dog does not influence the other.

Not everyone is a professional dog trainer, but you usually know if you have a good handle on your pet’s behavior. If you already experience difficulties training animals, perhaps chickens are not for you. Remember in some hierarchies, they fall into the “prey” category; be sure to predator-proof the coop (see the “Protection Against Predators” section of chapter 7). Even if you feel you have enough distance between your pets or sufficient control over them, always plan for the worst-case scenario. There will be a day when someone accidentally leaves a gate ajar or unlocked and your pet gets out and goes after the chickens. Plan your coop well—site it away from your dog kennel, for example—to prevent against this eventuality and others like it.

A dog can be a chicken’s best friend against predators once he finds common ground and bonds with the flock.

CONSIDER WHAT’S IN YOUR YARD

The yard itself can present all sorts of challenges to consider before bringing home chicks or setting up shop for a flock. A chicken spends about 60 percent of her day exploring her surroundings, searching for food or other interesting objects. While she performs this exploratory behavior, her attention is divided, making it even more important for the yard to be clear of dangers and safe from predators.

Birdfeeders can attract diseased birds as well as a variety of predators. Place yours far enough away from your chicken’s grazing area to be safe.

Birdfeeders

Birdfeeders can attract disease-carrying wild birds (see the “Biosecurity” section in chapter 10) so you must view them as “dirty.” Birdfeeders carry disease.

If you already own a birdfeeder, you really have two options: Get rid of it altogether or relocate it as far away from the coop as possible. Place it in the front yard, for example. If you want to keep the feeder, make it the absolute last stop in your daily routine, after you’ve finished with your chickens. Also, fill and clean your feeder at an area or sink separate from the one you use to fill and clean your chicken’s equipment. Now that’s good biosecurity!

Beneficial and Poisonous Plants

The list of vegetables and fruits chickens will eat is long and includes almost anything you eat. Many of the garden plants to which you expose your chickens are fine for them to peck at, but they shouldn’t eat the seedlings. Rather than cause yourself woe, wait until your garden matures before letting in your bug-eating, garden-tilling flock. (Even then, you may still need to block off areas of the garden you want your hens to avoid.)

NATURAL INSECTICIDES

In terms of plants and trees to place around—not in—your coop, consider these, which have natural insecticidal properties (find out more information about them from your cooperative extension office).

These plants aren’t good for your chickens to eat, but they may prevent the forward-march of mites or lice toward your flock.

Chrysanthemums (Chrysanthemum morifolium)

Bay laurel (Laurus nobilis)

Artemisia or wormwood (Artemisia vulgaris)

Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia)

Tansy (Tanacetum vulgare)

Comfrey (Symphytum officinale)

Neem tree (Azadirachta indica)

POISONOUS PLANTS

Finally, let’s look at poisonous plants. Because they’re often difficult for the average homeowner to identify, we recommend consulting your local extension agent or master gardener. Keep in mind that seasonal seeds, pods, or acorns—which you may not see at the time of year when you’re readying your coop—can also pose risk, so plan ahead when you are choosing a site for your coop.

The toxicity of these plants may be restricted to their seed, a particular part of the plant, or a stage of growth, so read up before landscaping with some of these plants. It’s not necessarily the first bite you should worry about, but rather chickens consuming large quantities over time.

Shown here are some poisonous plants to remove from your yard.

Foxglove (Digitalis purpurea)

Nightshade (Atropa belladonna)

Oleander (Nerium oleander L.)

Black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia L.)

Bladderpod/bagpod (Isomeris arborea)

Castor bean (Ricinus communis)

Corn cockle (Agrostemma githago L.)

Crown vetch (Coronilla varia L.)

Death camas (Toxicoscordion venenosum)

Jimsonweed/thorn apple (Datura stramonium)

Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca)

Poison hemlock (Conium maculatum)

Pokeberry (Phytolacca Americana)

Rattlebox (Crotolaria verrucosa)

Water hemlock/cowbane (Cicuta maculata)

Yew (Taxus baccata)

READYING THE YARD

Your yard’s almost ready for chickens. Here are a few other factors to consider.

Fencing for Pasture Rotation

If building a coop for the first time—and you don’t opt for a mobile one—carefully consider the outdoor area. (Chapter 7 discusses coops in detail.) The most up-to-date thinking in chicken-coop planning has moved away from a single outdoor run toward a coop with four runs. The more outdoor runs or pastures available to the chickens, the better it is for your flock because one spot doesn’t become a denuded, muddy mess. With only one run, a mess is guaranteed.

Plant different grasses and forages in each run. For example, in one, grow shade cover such as sunflowers or corn among shorter grasses. This will allow your chickens a shady run in the height of summer that is also edible later in the season. In different pens, spread out tall fescue, Bermuda grass, and alfalfa, as well as red, white, and ladino clovers. Chickens love clover and can quickly decimate a pen filled with it; plant clover in conjunction with another grass to keep the pen usable for longer. The notion of maintaining multiple runs will require you learn more about grasses or forages than if you had a single run, but it is one of the most modern concepts in coop planning.

Exclusion of predators is important for these outdoor runs, so bury the bottom of chicken wire or use electric fencing. Any aviary netting over the top of the outdoor runs should be taller than the tallest family member who must enter.

A Rock Border

When you design your outdoor runs, keep in mind the daily activities that take place in your yard: lawn/yard maintenance, sprinklers spraying, children playing, or people eating on the patio. Each of these has the potential to stress your flock. Mowing the lawn, for example, means bringing out a loud, scary machine. Build a 12- to 18-inch (30 to 45 cm) rock or dirt border around the coop and runs. This prevents the machine from getting close to the pen’s edge, therefore reducing fear in the birds. To make mowing a positive experience for your flock, make your first pass with the lawnmower one that blows clippings directly into the pen for the chickens to eat. Or gather the clippings in a sweeper and dump them into the pen for a tasty treat for the chickens. Don’t do this if you treat your lawn with harsh chemicals, as it may harm the birds.

Do your best to keep the grass cut and the weeds low around the coop. Having a border around the coop means less weed removal because fewer weeds will grow in that spot. Also, low grass prevents rodents from building a highway in the weeds that can grow up next to coops.

Sprinklers

Direct sprinkler systems away from the feed containers and pens because the water can quickly make the pen muddy and the feed moldy. If you wish for your yard sprinklers to also water the runs, consider running them at night when the flock is inside and not likely to get soaked. Chickens tend to stay inside on rainy days because they dislike getting wet.

Human Activity

Children running around playing can scare a new flock. The birds must get used to balls, loud toys, and shouting by children. Teach the younger members of your family to treat the coop and its flock with respect. Also, consider the smoke of a barbeque and activity of dinner on the patio. Chickens do not like smoke that drifts into and lingers in the coop. Also, chickens beg for treats just like any other pet, so unless you want to hear their cackle and endure hens’ stares throughout your dinner, erect a visual barrier between the chickens and where you cook and eat.

This chapter provided you a few details for your consideration, pointers meant to help you give your chickens an excellent overall experience. In the coming pages, we turn to chick incubation, brooders, and coops.

Children can hardly contain their enthusiasm when they see an active flock of hens and chicks, but they need to be taught the proper way to handle poultry.