CHAPTER 7

Welcome to Jurassic Park

In addition to being an enormously entertaining movie, Jurassic Park (1993) is a cautionary tale of technology gone wild. The film, and Michael Crichton’s novel from which it was adapted, are modern twists on the ancient Prometheus myth and Mary Shelley’s nineteenth-century horror story Frankenstein, in which an obsessed Dr. Victor Frankenstein dared to play God and created a monster that destroyed everything most dear to him. Misusing technology is an age-old tale that visited Wall Street in 2008 with dire results.

In one scene in Jurassic Park, the scientists who are brought to the park to evaluate its progress and safety for its insurers and financiers get into a heated debate over lunch with the park’s founder, Dr. John Hammond, about the merits of trying to fool with Mother Nature. They had just witnessed a velociraptor devour a cow in a matter of seconds in a display of savagery that, among other things, renders them uninterested in their meal. Dr. Ian Malcolm, a professor of chaos theory (brilliantly played by the actor Jeff Goldblum) begins shouting at Dr. Hammond that he is tempting fate by blindly using technology without respecting its potentially destructive power:

The problem with the scientific power you’ve used is it didn’t require any discipline to attain it. You read what others had done and you took the next step. You didn’t earn the knowledge yourselves, so you don’t take the responsibility for it. You stood on the shoulders of geniuses to accomplish something as fast as you could, and before you knew what you had, you patented it....Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could that they didn’t stop to think if they should.1

The hubris involved in creating extinct creatures out of the DNA stored in amber buried deep in the earth is an apt metaphor for the derivatives technology that was unleashed on the financial world through the creation of credit default swaps. The ruins of the imaginary Jurassic Park serve as a vivid image of a damaged financial system once credit defaults swaps and other exotic derivative instruments backfired on their inventors in 2008. The fact that the film came out at roughly the same time that a group of investment bankers from JPMorgan created these new types of financial instrument simply lends some irony to the history of one of the greatest self-inflicted wounds in financial history.2

Isla Nublar

Financial derivatives are very odd animals. As Edward LiPuma and Benjamin Lee point out in a brilliant theoretical discussion of derivatives in their book Financial Derivatives and the Globalization of Risk, derivatives are a unique form of capital. Unlike currencies, derivatives do not gain their value or legitimacy from the backing of any government or any precious metal.3 Unlike bonds or bank loans, derivatives do not draw their value directly from an underlying obligor (in other words, the company whose financial condition will determine whether they will be repaid). Instead, a derivative is a hybrid creature whose value is drawn from two entirely separate sources. In this discussion, we will focus on credit derivatives in their most common (and potentially noxious) form: credit default swaps (CDS).

Financial derivatives are the ultimate (so far—there will undoubtedly be further applications of computer technology to financial instruments) example of the literal deconstruction of financial instruments. The importance of the ability to deconstruct financial instruments through computer technology cannot be overemphasized; it transformed the nature of financial assets by turning them into immaterial objects of untold complexity. The digitalization of information was a key step in the process of financialization because it broke down the boundaries between different disciplines and modes of communication. Computers create the ability to reduce language and symbols into the common language of 1s and 0s in a manner that disguises or blurs differences in meaning between different types of underlying objects or forms.

Derivatives could not exist without the type of computing power that developed over the past three decades. Digitalization takes one thing—a financial instrument (a bond, stock, mortgage, loan, and so on)—and turns it into another thing: another financial instrument (a derivative). This transformation reveals the fact that these instruments are really just different combinations of the same constituent parts, much like humans and animals are different combinations of DNA or each component of the periodic table is a different combination of electrons and protons. This has tremendous ramifications for the way in which financial market participants come to view the world. It is also an enormously destabilizing force because it separates the tradable instrument from the underlying reference instrument, just as securitization in the credit markets sunders the promissory relationship between the borrower and the lender. As relationships between things that were previously connected become further separated or mediated, the opportunity for the confusion of meaning and disruption of relationships increases.

Credit derivatives disassemble bonds, loans, and mortgages into their constituent parts and then reassemble them into new configurations that can be sold to different investors (or speculators) with different risk appetites. Derivatives are the financial version of splitting the atom or dissecting the human genome. Just like nuclear weapons draw their potency from the ability of scientists to split the atom into its constituent parts, derivatives derive their power from the ability to separate financial instruments into 1s and 0s, the constituent parts of money. The problem with deconstructing a debt instrument into its constituent parts is that it abstracts the new instrument—the derivative—from its underlying or reference obligation in a manner that attenuates the relationship between lender and borrower and vests economic power over the ultimate borrower in the hands of a party that has little or no knowledge about or interest in the actual business or economic fate of this borrower.

To describe this product in the language of Karl Marx, a credit derivative like a credit default swap is the quintessential fetish instrument because it is the result of a process whereby an underlying financial instrument (a bond, bank loan, or mortgage) is deconstructed into its constituent parts and then reassembled or reconfigured into a new form that has no resemblance to the economic forces that created it. In most cases, investors who buy or sell derivatives are speculators who have no interest in or understanding of the underlying instrument or the social relations that brought it into being. This is a far more radical state of alienation than simply saying that we are no longer getting our mortgage from our neighborhood banker. The relationship between lender and borrower, the two parties to a promise, has become so attenuated as to become almost spectral. Derivatives are the ultimate manifestation of disembodied financial relationships controlled by forces that are difficult to identify or control.

Highly mediated forms of finance such as securitization and derivatives impose enormous barriers between underlying financial instruments or securities and the forms in which they are traded. When every financial object is capable of being transformed into something else, all financial instruments are revealed to be, in their essence, the same. This chameleon-like quality introduces a degree of instability into the system that did not exist before derivatives technology came to dominate markets. This instability arises from the fact that the identity and character of individual financial objects such as stocks, bonds, or mortgages can be transformed into different types of objects. Just as the ability of a traditional convertible bond to be exchanged for stock drastically changes the way it is valued compared to a nonconvertible bond, the ability of a traditional corporate bond to be pooled with other bonds into a collateralized bond obligation (CBO) or expressed in terms of a credit default swap alters its value in multiple ways by changing its liquidity and other characteristics. For investors, this raises profound questions regarding asset allocation and other traditional theories of portfolio management that some of us have long questioned. For instance, the very concept of asset classes must be called into question in view of the ability of derivatives to turn one type of security into another type of security. Such questions have enormous asset allocation consequences that are just beginning to be explored by thoughtful money managers and regulators.

Credit default swaps are legally enforceable insurance contracts in which two parties enter into an exchange of promises with respect to an underlying financial obligation, for example, a bond, bank loan, or mortgage. Neither of these parties is required to have any legal relationship (for example, a preexisting ownership relationship) with the company that issued the underlying obligation. In fact, the presence of a preexisting relationship is the factor that separates speculative derivatives positions from hedged derivatives positions. The latter involves parties who already have an ownership interest in the underlying obligation and are using the derivative to protect themselves from losses, while the former involves parties with no such ownership position who are merely betting on price movements in order to earn a new profit. Another component of the value of a derivatives contract is found in the parties who enter into the contract. Their financial condition and ability to fulfill their promises are keys to the outcome of the contract into which they have entered.

The contractual nature of derivative instruments is essential to their understanding.4 As contracts, derivatives share certain important similarities with other credit instruments such as mortgages, bank loans, and bonds. Wherever they circulate in the economy, they must return to their point of origin for redemption (i.e., payment). Once the contract is satisfied, it disappears from circulation. As we saw in Chapter 4 discussing mortgage derivatives, the disembodied nature of these contracts can cause serious practical problems, for example, when it becomes impossible to identify who holds the mortgage on a home because the mortgage contract was sold into a large mortgage pool and cannot be tracked. Unlike the underlying cash obligations on which derivatives are based, derivatives are disembodied from the flesh-and-blood borrowers whose economic performance determines their ultimate value.

An essential component of a derivative contract’s value is based on the parties’ ability to enforce their rights within a system of laws. There are two aspects of enforceability. First, theoretical or legal enforceability is based on the specific language of the derivatives contract. The contract sets forth the respective obligations of the parties and the consequences of failing to meet them. Second, practical enforceability is wholly dependent on the ability of the parties undertaking financial obligations under the contract to fulfill them. In theoretical terms, a legally unenforceable promise made by a solvent party is worthless, while in practical terms a legally enforceable promise made by an insolvent or unwilling counterparty is an empty promise. Both the theoretical and practical aspects of enforceability must be present for a derivatives contract to be fulfilled.

The second component of value in a credit default swap contract is the underlying security itself. Changes in the price of this security play a determinative role in the value of the derivatives that are based on them. The indirect nature of a derivative obligation—the fact that its value is determined by reference to something outside of itself—renders it unusually complex and inherently unstable because it is subject to variables beyond the control of the parties to the contract. Moreover, unless regulatory or other legal limits are placed on the ability to issue derivatives with respect to an underlying obligation, there is no theoretical limitation on the volume of derivative contracts that can be written with respect to a specific underlying obligation. This raises particularly important systemic questions with respect to credit derivatives and credit default swaps specifically, which are discussed in detail in the following section.

At times during the 2008 financial crisis, it seemed as though the fiscal and monetary authorities were not going to be able to stop the markets from collapsing. The reason for this feeling of helplessness was not simply the volume of selling that was raining down on the markets, but the fact that it was difficult to identify the source of selling and the reasons for selling. This was particularly true with respect to credit instruments such as mortgages, bonds, and bank loans, the prices of which were driven to levels that made no rational sense unless one truly believed that the end of the world was at hand.

What was not apparent to market observers (in particular the media) was that selling pressure was being generated in the parallel universe of the credit derivatives markets, which were completely opaque and unregulated and whose prices were largely hidden from the media and the public. Price discovery—the term traders use to describe the point at which buyers and sellers come to a meeting of the minds—became a matter of shooting darts in the dark because there were no benchmarks against which to measure value. This was because the traditional benchmarks—the prices of cash credit instruments—were being driven by the shadow prices of their derivatives, whose markets were concealed from view and driven by mathematical formulas that had little or no relation to the real world in which these obligations were functioning and affecting real flesh-and-blood human beings. When the distance between lender and borrower became so attenuated as to become akin to that between a body and its ghost, it was not unreasonable to fear that regulators and governments would not be able to put the genie back in the bottle again.

More frightening is the fact that the spectral world of derivatives is not subject to the physical limitations of the underlying obligations to which they refer. The parallel universe of credit derivatives dwarfs the cash obligations with respect to which they are written. In the most widespread type of credit derivative and the one that will occupy most of our attention here—credit default swaps—the market grew to more than $60 trillion in size on the eve of the 2008 financial crisis, far greater than the volume of cash obligations it was insuring. The sheer size of this market came to exercise an enormous and often perverse influence on the world of cash credit obligations. Like Frankenstein, the creature who turned on and ultimately destroyed all that mattered most to his master, credit default swaps created horrific unintended consequences for borrowers and lenders.

The New DNA of Finance

At its core, a credit default swap is an insurance contract in which one party (the seller of protection or insurance) promises to pay the other party (the buyer) in the event that an underlying financial obligation (normally a bank loan, bond, mortgage, or pool thereof) defaults. The seller/insurer pays the buyer/insured an amount of money that will compensate for the loss. Most economists and educated market practitioners agree that using a credit default swap to hedge an existing holding of a credit instrument is a rational and socially and economically valuable and useful activity.

A couple of simple examples will demonstrate the idea behind credit default swaps.

The first example involves bonds of Microsoft, Inc. (MSFT), a financially sound company:

Institution A owns $10 million of MSFT bonds. The bonds are trading at par (100). It is concerned that changes in interest rates may cause the price of these bonds to drop and wants to buy insurance against such an event. It goes to Institution B to purchase that insurance. The cost of such insurance is 150 basis points per year for $10 million of insurance for a five-year period, or $150,000 per year. This amount is paid annually pursuant to a standard contract known as an International Swap Dealers Association (ISDA) contract.

In addition, the buyer of protection is required to post some amount of collateral with the seller to insure his ability to make future premium payments. The collateral amount is determined by a combination of factors that includes both the credit quality of the buyer/insured as well as that of the underlying instrument. One of the reasons that the credit default swap market was able to explode in size was that collateral requirements were relatively small prior to the 2008 crisis.

Collateral is a much bigger issue with respect to our next example, a financially distressed company like General Motors Corp., in the months before it filed for bankruptcy in early 2009. In the case of a failing company, default insurance is much more expensive to purchase because the likelihood of default is very high (the insurer is highly likely to be making good on his promise to make the insured whole for his loss). The buyer of protection is required to post more collateral, and the cost of insurance includes a large upfront payment as well as large annual payments. Most of the premium, however, is captured in the large upfront payment.

Institution A owns $10 million of General Motors bonds. The bonds are trading at 20 cents on the dollar. It is concerned that General Motors may default on these bonds and wants to buy insurance against such an event. It goes to Institution B to purchase that insurance. Because the odds of General Motors defaulting are very high, Institution B demands both an upfront payment and an annual premium for this insurance. The upfront payment is 45 points, or $4,500,000, and the annual premium is $500,000, for a five-year period. This insurance agreement is documented in a standard contract known as an ISDA contract.

One might inquire why an investor would pay such an exorbitant amount for default insurance. The answer is that he wouldn’t. Trades of this type occur among speculators, not investors looking to hedge existing positions. Holders of General Motors bonds or loans who were worried about credit losses arranged to hedge (or sell) their positions much earlier, when credit insurance was still cheap. At the point where large upfront payments are involved, speculators have taken over and are placing bets on the timing of default and the likely recovery value on the swap contracts.

These examples illustrate the differences between the pricing on credit default swaps for distressed borrowers and for healthy borrowers. In fact, one might ask whether there is a need for credit default swaps on healthy borrowers, and this is where the distinction between hedging and speculation comes into play. Many investors must mark-to-market their investments on a current basis, and other investors are not required to do so. Increasingly, the investment world has moved to a mark-to-market model in which institutional investors require their investment managers to value their assets on a current basis. In recent years, this trend has been accentuated by the explosive growth of hedge funds and changes in accounting rules aimed at increasing systemic transparency.

Marking-to-market is a complex issue and a two-edged sword. In the case of short-term oriented investors such as hedge funds, marking-to- market is an appropriate requirement. If an investor has a short-term time horizon, he should be required to value his assets on a current basis. But in the case of banks, which are in the business of making long-term loans on assets that are often illiquid, or long-term investors such as pension funds that are trying to match long-term liabilities with long-term bond holdings, marking-to-market may not be appropriate. Nonetheless, there is growing sentiment that mark-to-market accounting should be used more broadly in the financial world. As a result, an increasing number of investors feel the need to hedge their investment holdings, particularly longer dated ones; and one of the primary tools for doing so in the fixed-income world is credit derivatives, and specifically credit default swaps. The primary risk involved in investing in a high-quality investment grade bond is interest rate risk rather than credit risk. Accordingly, the holder of a Microsoft bond is primarily concerned about price changes in the bond resulting from changes in interest rates, not radical changes in Microsoft’s financial condition. A credit default swap is a useful way to hedge this risk. The value of the credit default swap will change as the value of the underlying Microsoft bond changes in response to changes in interest rates (or, if there are significant changes in Microsoft’s credit quality, to those changes as well). As a result, the investor will be able to counterbalance losses or gains in the underlying Microsoft bond with corresponding gains or losses in the credit default swap contract on those bonds. This hedging function is eminently reasonable and serves an important and useful purpose in financial markets.5

The problem with these instruments arises from the fact that they are untethered from the underlying bonds and there is no practical or theoretical limitation on the amount of credit default swaps that can be written with respect to any given underlying bond, loan, mortgage, or pooled instrument. In practice, this means that if there are $2 billion of outstanding General Motors bonds, the amount of credit default swaps that can be written on those bonds is not limited to $2 billion. It can be $20 billion, or $200 billion, or $2 trillion. The net exposure (in other words, the actual amount of money at risk when offsetting trades are removed from the system) may be much less than the outstanding face amount of credit default swaps, but there is no systemic or regulatory limitation on the amount of these instruments that can be written by market participants. This is how the credit default swap market grew virtually undetected to over $60 trillion in size by early 2008 and came to threaten the very viability of the global financial system. And as noted in the Introduction, it is the notional (gross) rather than the net exposure that matters in a crisis because that is precisely the time when counterparties are unable or unwilling to perform their contractual obligations with respect to these instruments. That is what happened in 2008, triggering the crisis.

There are far more complex variations of credit default swaps. These are easier to understand if one keeps in mind that they are intended to be insurance against losses on underlying obligations. One such example is a credit default swap written on a single tranche of a collateralized debt obligation (CDO) that holds pools of residential mortgages. These were discussed earlier in this book (see Chapter 4). In this example, a credit default swap is written with respect to specific tranches of a collateralized mortgage obligation (CMO) in order to provide insurance for an owner of that tranche’s bonds against a default of those bonds. For example, if a holder of one of the 17 tranches in the CMO shown in Figure 4.3 in Chapter 4 wanted protection against a default on his bonds, which would result if enough of the underlying mortgages held by the CMO defaulted, he would ask a financial institution to sell him protection in the form of a credit default swap. Depending on whether the tranche in question was considered healthy or distressed, he might pay an upfront premium plus an annual premium (for a distressed junior tranche) or just an annual premium (for a healthy senior tranche). This would provide him protection if the CMO ran into trouble and defaulted.

Finally, there is an even more complicated variation, known as a credit default swap written on a synthetic CDO. A synthetic CDO holds a pool of other credit default swaps on underlying bonds, loans, or mortgages (rather than owning the underlying bonds, loans, or mortgages themselves). In other words, a synthetic CDO does not own a pool of individual bonds or loans or mortgages but instead is a counterparty to credit default swap contracts on underlying bonds, loans, or mortgages. Like other CDOs, this type of CDO is financed through the sale of different tranches of rated debt. Holders of these different tranches can buy insurance against potential losses on these tranches by buying protection through credit default swaps. Alternatively, speculators (those who don’t own the underlying tranches) can place bets on whether the underlying tranches will increase or decrease in value. Needless to say, such instruments are highly complex, extremely illiquid and difficult to unwind in market dislocations.

Warning Signs

By early 2006, the credit derivatives market was already spinning out of control. In any other industry, there would have been more than enough embarrassment to go around when it was discovered that a huge percentage of credit default swap trades had not been properly accounted for by Wall Street’s back offices. As of September 30, 2005, the number of trade confirmations that were outstanding for more than 30 days stood at 97,000. Assuming an average trade size of $5 million, this meant that trades with a nominal value of $485 billion, in the words of The Wall Street Journal, “lacked detailed confirmations—a problem that has left banks and brokerage firms uncertain who owes what to whom.”6 In a speech to the Global Association of Risk Professionals in early 2006, then New York Federal Reserve President Timothy Geithner stepped into the fray and read Wall Street the riot act about cleaning up its mess.

The post-trade processing and settlement infrastructure is still quite weak relative to the significance of these markets.... The total stock of unconfirmed trades is large and until recently was growing considerably faster than the total volume of new trades. The time between trade and confirmation is still quite long for a large share of transactions. The share of trades done on the available automated platforms is still substantially short of what is possible... firms were typically assigning trades without the knowledge or consent of the original counterparties. Nostro breaks, which are errors in payments discovered by counterparties at the time of the quarterly flows, rose to a significant share of total trades. Efforts to standardize documentation and provide automated confirmation services has lagged behind product development and growth in volume ... the assignment problems create uncertainty about the actual size of exposures to individual counterparties that could exacerbate market liquidity problems in the event of stress.

Wall Street, however, is not subject to embarrassment. The profit motive trumps everything else. So the large derivative trading firms promised to clean up the mess, and all was forgiven by the stern-faced Mr. Geithner and his regulatory brethren. The fact that Wall Street was unable to account for such a large portion of credit default swaps should have been a stark warning that trouble lay ahead. Little did anyone appreciate the depth of the problem or the risk it posed to the financial system. The monster was about to eat Manhattan.7

Dinosaurs Turn on Their Makers

Credit default swaps create a structure in which lenders are so alienated from the flesh-and-blood labor of the businesses that are responsible for repaying them that the traditional relationship between borrower and lender is not only sundered but in certain circumstances rendered adversarial. One of the dirty little secrets about credit default swaps is that they create in the buyer of protection (the insured) a strong economic incentive to see the borrower fail; in many cases, a default produces the highest possible payout and highest rate of return for the buyer of insurance. In this way, credit default swaps create perverse incentives for the parties that enter into them. Credit default swaps can create strong economic incentives for investors to root for businesses to fail because failure constitutes a “credit event” that triggers payment under the derivatives contract. Moreover, because the volume of credit default swaps can dwarf the amount of a company’s outstanding debt, the derivatives market rather than direct lenders can determine the fate of a debtor. This means that the parties calling the shots are not those who have an interest in the underlying business, the employees or the communities affected by whether a company can ultimately restructure its debts. Instead, power is vested in the hands of credit default swap holders who do not own the underlying debt instruments but who have instead merely placed bets, usually with very little money down, on the future of flesh-and-blood businesses. From a public policy standpoint, this raises serious questions about the proper role of debt and derivatives markets in the economy.

The somewhat perverse phenomenon of creditors rooting for the demise of their borrowers in the credit default swap market has been termed the “empty creditor” phenomenon by Professor Henry T.C. Hu of the University of Texas Law School.8 Professor Hu describes an empty creditor as “someone (or some institution) who may have the contractual control but, by simultaneously holding credit default swaps, little or no economic exposure if the debt goes bad.” In fact, “if a creditor holds enough credit default swaps, he may simultaneously have control rights and incentives to cause the debtor firm’s value to fall.” This concept gives a modern meaning to Karl Marx’s concept of alienation. Marx was speaking about the alienation of labor, but today the alienation of labor has been transformed into the alienation of capital. This type of alienation between borrower and lender can have an insidious effect on borrowers by making it more difficult for them to reorganize their debts.

The advent of credit default swaps creates a situation in which lenders can hedge their exposure to borrowers so effectively that they prefer to see their debts repaid by their counterparty rather than by the borrower itself. Such payment will come more quickly and is preferable to waiting for the borrower to pay after a lengthy bankruptcy or restructuring process. Accordingly, credit default swap buyers are incentivized to see borrowers fail. So-called “basis packages,” in which investors own both a bond and a credit default swap related to that bond, are often structured to deliver a higher return if the borrower files for bankruptcy, thereby forcing a payout on the credit default swap contract at the time of the bankruptcy filing (as opposed to the end of the bankruptcy reorganization process, which can take months or years). Rather than leading lenders to participate in a consensual out-of-court restructuring that generally imposes much lower costs on the borrower, this regime pushes borrowers into highly expensive bankruptcy proceedings that create little economic value for anybody but bankruptcy attorneys and restructuring advisors. In the hands of speculators who have no interest in the ultimate survival of the business (if they even know what the business is and what it does), businesses are reduced to empty carcasses whose bones are more likely to be sold in liquidation than emerge as viable going concerns with new, deleveraged balance sheets.

In the period leading up to the 2008 crisis, this economically unsound phenomenon was exacerbated by the fact that many debts were incurred in private equity transactions where much of the value was skimmed off into the hands of private equity sponsors through management, monitoring, and transaction fees rather than into the hands of the limited partners who represent endowments and foundations and other tax-exempt organizations. The combination of these factors led to a voiding of the value of leveraged companies into the hands of financial speculators. The government, through the bankruptcy process or, in the event of a systemically important company, through a bailout, was left to clean up the mess.

George Soros has written persuasively on the asymmetric incentives that credit default swaps introduced into the financial system. Soros views these flaws as sufficiently profound to call for these instruments to be banned unless the purchaser of credit insurance owns the underlying instrument. In an essay in The Wall Street Journal, he wrote the following:

Going short on bonds by buying a CDS contract carries limited risk but almost unlimited profit potential. By contrast, selling CDS offers limited profits but practically unlimited risks. This asymmetry encourages speculating on the short side, which in turn exerts a downward pressure on the underlying bonds. The negative effect is reinforced by the fact that CDS are tradable and therefore tend to be priced as warrants, which can be sold at anytime, not as options, which would require an actual default to be cashed in. People buy them not because they expect an eventual default, but because they expect the CDS to appreciate in response to adverse development. AIG thought it was selling insurance on bonds, and as such, they considered CDS outrageously overpriced. In fact, it was selling bear-market warrants and it severely underestimated the risk.9

Soros outlines what happens when you fool with Mother Nature. First, credit default swaps offer limited risk and unlimited reward when used to make negative bets on credit. Second, investments in credit default swaps require far too little collateral, which allows a small amount of capital to affect the market (something that remains true even after post-crisis reforms increased collateral requirements). This disconnection with the real economy is what raises concerns about the role that derivatives play in today’s markets. The problem with this, as LiPuma and Lee point out, is that speculative derivatives positions (i.e., those not being used to hedge an underlying position) do not appear to involve productive labor, the organization of activities that have any real connection with material resources, the output of goods or services, or the satisfaction or promotion of further productive output.10 As a result, these instruments can be used to speculate on credit without the speculators being sufficiently at risk to cause them to think twice about the potential systemic risks they may be posing. For these reasons, Mr. Soros’ argument for banning naked default swaps is compelling.

Bear Stearns: First Casualty

The collapse of Bear Stearns in 2008 illustrated some of the systemic risks that unregulated trading in credit default swaps created. Speculators were able to take aim at the firm’s stock and credit default swaps and engage in a variety of short-selling strategies in an effort to profit from price changes (a drop in the stock price, or an increase in its credit default swap spreads) without any regard for the real-world consequences of their behavior. The rating agencies then stepped in and threatened to lower the company’s credit rating based on these manipulative price movements, rendering the company incapable of financing itself. The inner workings of the credit default swap market were able to produce changes in Bear Stearns’ borrowing costs that battered the firm’s financial condition and contributed to its demise.

Bear Stearns met its maker in March 2008. At the time (and at all times), broker dealers had extensive counterparty exposure to each other. Each firm places limitations on how much overall exposure it is willing to have to another firm. If one trading desk has a certain amount of exposure to another firm, it will limit how much exposure other desks can have to that same firm. As a result, each firm has a limited ability to write credit default swaps on another firm’s credit. At the time, these limitations were even tighter because of the building crisis. Since firms had to limit their exposure to Bear Stearns, every time a firm was asked to increase its exposure to the firm by writing another credit default swap, it raised the price. In an illiquid market, these price increases were disproportionately large. This led Bear Stearns’ credit default swap spreads to spiral out of control. In effect, the internal workings of the credit default swap market caused Bear Stearns’ collapse to become a self-fulfilling prophesy by rendering Bear Stearns’ cost of funding so expensive as to render the firm incapable of financing itself. Without the ability to finance itself, a broker dealer like Bear Stearns had to close its doors (or sell itself to someone like JPMorgan Chase & Co. for a nominal amount).

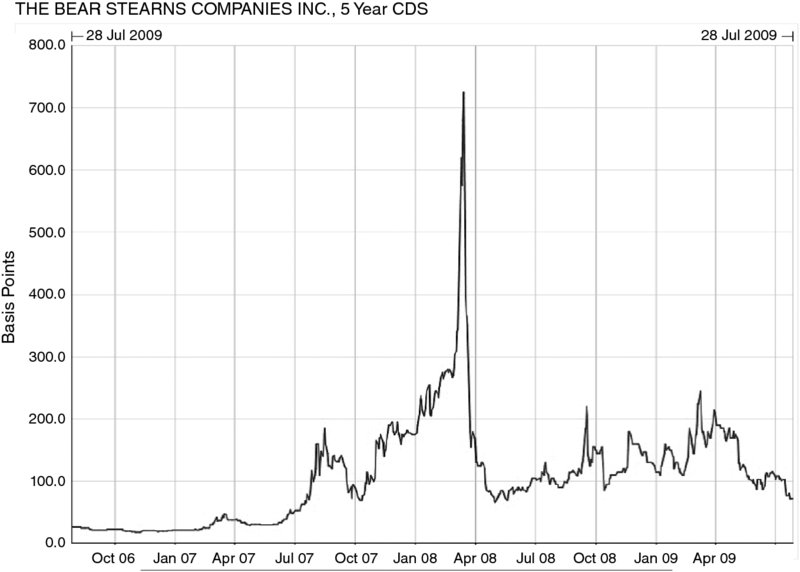

In the case of Bear Stearns, sharp increases of its credit default swap spreads in the period leading to its takeover by JPMorgan Chase signaled to the media and markets that the firm was experiencing financial trouble. During the week of March 10, 2008, Bear Stearns’ one-year credit default swaps spreads suddenly spiked to nearly 1,000 basis points, a level that rendered the investment bank incapable of financing itself or running its business profitably. A financial institution uses money as its raw material, and when the price of its raw material is driven up by a factor of 10 virtually overnight, it is effectively priced out of business. This is exactly what happened to Bear Stearns. Figure 7.1 shows the dramatic spike to unsustainable levels to which Bear Stearns’ credit default swap spreads were driven before the company was sold to JPMorgan Chase & Co.

Figure 7.1 Bear Stearns’ Death by CDS

SOURCE: Goldman Sachs, July 2009.

An investment bank and trading firm requires low-cost overnight funding in order to profitably hold trading inventory, and these levels were telling the marketplace that Bear Stearns could no longer borrow at reasonable rates if at all. This was a far more important indication of financial distress than the firm’s stock price, which was also plunging at the time.11

Credit default swap spreads, because they are quoted in real time, are believed to be the most accurate and timely indicia of a borrower’s credit quality. Unfortunately, there are several flaws with the concept of depending on the credit default swap market to determine the fate of important financial firms. Bear Stearns maintained active trading relationships with virtually every other financial institution in the world. Its failure would have caused severe disruption throughout the financial system (much as Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy six months later actually did). The credit default market was completely unregulated. A few trades and a relatively small amount of capital were capable of moving spreads by an inordinate degree. A major financial institution and the entire financial system were effectively held hostage by a credit default swap market in which participants could place large bets with relatively modest amounts of capital (the collateral requirements for these trades were far lower than stock margin requirements). Moreover, the market was highly illiquid (that is, a relatively small volume of trades was capable of having a disproportionately large effect on Bear Stearns’ spreads). As a result, a relatively small number of traders, and a relatively small amount of capital, were likely responsible for widening Bear Stearns’ credit default swap spreads to levels that suggested that the firm was at imminent risk of failure.

In March 2008, swap traders were operating with extremely limited information and mostly working based on rumor and innuendo. There is nothing more opaque or subject to rapid change than a trading house’s balance sheet. Moreover, there was credible evidence that some of the firm’s competitors were participating in, or at least encouraging, what amounted to a “bear raid” (excuse the pun) on the firm through the credit default swap market. In Wall Street parlance, a bear raid involves a group of speculators acting together to raise doubts about the viability of a company and profiting from that firm’s failure by selling short its stock (or, in this case, its bonds and other credit instruments). Since credit default swaps at the time were effectively unregulated, there was nothing Bear Stearns could do to stop the speculation and its sale to JPMorgan Chase (at the behest of the U.S. government) for $2 per share (later adjusted to $10 per share.) At its peak in January 2007, the stock had sold for as much as $171.50 per share (which was undoubtedly far more than it was worth). Bear Stearns was hardly a poster child for risk management, but being victimized by credit default swap speculators was an unfortunate ending for a storied Wall Street firm.

American International Group (AIG)— Second Casualty

Credit default swaps reappeared as weapons of financial self-destruction six months later at insurance giant American International Group (AIG). AIG was once the pride of the global insurance industry. The company morphed into a multifaceted financial institution that was part hedge fund, part investment bank, part asset management company, and part insurance company. Unfortunately, the firm came to be dominated by a group centered in London and Connecticut known as AIG Financial Products. This group of financial engineers came to believe that AIG’s AAA balance sheet empowered it to write infinite amounts of insurance on investment grade-rated risks without ever asking what would happen if those credit ratings were questioned. By the middle of 2007, the company had insured a reported $465 billion of investment grade securities. But this exposed the company to two types of risks with respect to credit ratings. The first was that the ratings on all of the AAA securities that it was insuring had to stay AAA. The second was that its own investment rating had to remain AAA. Unfortunately, AIG came to learn that these were the same question, and the answer was not the one it expected to hear.

In September 2008, AIG found itself facing approximately $27 billion of collateral calls on $62.1 billion of credit default swap contracts on synthetic collateralized mortgage obligations. A synthetic collateralized mortgage obligation is a pool of credit default swaps on different tranches of underlying pools of mortgages. These assets are typical of those that lay at the heart of the financial crisis. They were highly complex, illiquid mathematical constructs that few people understood (least of all, apparently, the people at AIG that were purporting to insure them) and few institutions wanted to own, which is why so much effort was made to lay off their risk. They travel in the guise of securities, yet they are not securities in the traditional sense of the word. In fact, as the world came to learn much to its dismay, that term is the quintessential oxymoron—whatever these constructs are, they are the farthest thing in the world from secure. They have little to do with the fundamental credit quality or earnings quality of a company or an economic entity or actor. They merely reference some other entity that references some other entity and so on in an endless daisy chain to hell.

Yet in this case, the reason for AIG’s crisis lay not in these monstrosities but in itself: AIG was about to lose its own highly coveted AAA rating. On Friday, September 12, 2008, Standard & Poor’s placed AIG on negative credit watch, suggesting that loss of its coveted AAA rating was imminent. The insurance giant didn’t have to wait long to learn what “imminent” meant in the midst of a financial crisis. Just three days later, on Monday, September 15—the same day that Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy—Standard & Poor’s and the two other major credit rating agencies, Moody’s Investors Service and Fitch Ratings Service, downgraded the long-term credit rating of AIG. The game was up. For many companies this might be bad news, but it would not trigger corporate destruction. However, AIG’s credit default swap agreements included a clause that required the insurance giant to post additional collateral if it lost its AAA rating. Such a provision is not particularly unreasonable or even unusual; if a party’s credit quality deteriorates, it is reasonable for those doing business with it to ask for additional assurance that they will be repaid. In the case of AIG, however, this clause triggered a requirement to post $27.1 billion of additional collateral with respect to the synthetic collateralized mortgage obligations in question. But AIG simply did not have that kind of cash lying around in its vaults. Obviously, nobody at AIG ever envisioned a ratings downgrade.

The U.S. government was faced with little choice but to step in and provide AIG with the cash to make these collateral payments. AIG was much larger and more interconnected with the rest of the global financial system than Lehman Brothers, whose bankruptcy was shaking the financial system to its core. As I warned in The New York Times on September 16, 2008, AIG’s failure would have been an extinction-level event for the global financial system, triggering cross defaults on all of AIG’s other contracts (derivative and otherwise) around the world.12 It would also have set off a maelstrom of defaults among the thousands of financial counterparties around the world that were depending on AIG or other parties for payments in order to meet their own obligations.

It remains an interesting question whether the U.S. government solved the problem in the right way. The credit rating agencies could have been told to back off and maintain AIG’s AAA rating (although that would have been unlikely to fool the market, and AIG’s own credit default swap spreads probably would have widened significantly and driven the company into insolvency). Alternatively, the U.S. government could have simply stated that it would stand behind all of AIG’s financial obligations, effectively lending AIG the U.S. government’s AAA rating. While there was no express legal authority for such a move, the Federal Reserve had little trouble invoking its emergency powers at other times during the crisis in the name of systemic stability.13 This approach would have avoided the necessity of the U.S. Treasury coming up with what ultimately became approximately $175 billion in support for AIG (although the government ultimately earned a $23 million profit on its investment). The market was willing to accept U.S. government guarantees on other failed institutions such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, so it likely would have been satisfied with one on AIG. But whether or not the bailout could have been done more effectively, the authorities clearly did the correct thing by stepping in and preventing AIG from failing. The real tragedy (and farce) is that AIG found itself in that position in the first place through the irresponsible issuance of hundreds of billions of credit default swap obligations.14

The fact that the failure of Lehman Brothers and the near-failure of AIG occurred at virtually the same time was a sign that the financial markets had ceased to function. Capital died. The damage soon spread to two other firms that were considered by most observers to be well-managed and well-capitalized: Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley. During that same week in September 2008, credit default swap traders had their way with these companies as well. To place the following numbers in context, remember that Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy on Monday, September 15, (and was obviously rumored to be in trouble in the days leading up to that date). The five-year credit default swap spreads for Goldman Sachs moved from 200 basis points on Friday, September 12, to 350 basis points on Monday, September 15, and then to 620 basis points two days later on Wednesday, September 17 (by then the government had announced an $85 billion rescue package for AIG). Morgan Stanley saw even more ominous widening in its spreads, from 250 basis points on Friday, September 12, to 500 basis points on Monday, September 15, to 997 basis points on Wednesday, September 17. Wall Street was devouring its own. At these spreads, no firm could finance itself profitably for very long. Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley moved quickly to raise billions of dollars of new equity capital from outside investors in order to bolster their balance sheets and were granted bank holding company status by the U.S. government in order to obtain further protections.

The Bond Insurers—Third Casualty

Another group of companies that were ruined by their exposure to credit default swaps with serious systemic ramifications were the bond insurers led by Ambac Financial Group and MBIA, Inc. Both of these companies started out in the business of insuring municipal bonds. Since managing municipal bonds requires very little intellect or imagination, municipal bond insurance is a business that really should not exist. Municipal bonds rarely default; managers who invest in those that do are in the wrong line of work, but that is a story for another day. As the margins in that business shrunk, Ambac and MBIA looked for greener pastures and found them in the world of structured products. They could not have moved from a more mundane and simplistic product (municipal bonds) to a more arcane and complex one (collateralized debt obligations). As a result, they were poorly equipped intellectually and institutionally to deal with their new business. Nonetheless, like AIG, they were clever enough to discover (in another example of why we should not confuse education with smarts or the ability to make money as an investor) that they could use their own AAA ratings to begin insuring the AAA tranches of CDOs.

As in the case of AIG, this strategy was wholly dependent on the rating agencies continuing to maintain their AAA ratings on the bond insurers as well as on the underlying securities in the senior tranches of CDOs. And as with AIG, the rating agencies pulled rugs out from under both Ambac and MBIA. On January 17, 2008, Moody’s placed Ambac’s AAA credit rating on watch for possible downgrade. This was well after it was apparent to everyone other than Moody’s that the mortgages in the CDOs insured by Ambac were defaulting in record numbers. Moody’s cited Ambac’s announcement that it expected to record a $5.4 billion pretax ($3.5 billion after-tax) mark-to-market loss on its portfolio of credit default swaps written on CDOs for the fourth quarter of 2007, including a $1.1 billion loss on certain asset-backed CDOs. Moody’s stated with a straight face that “this loss significantly reduces the company’s capital cushion and heightens concern about potential further volatility within Ambac’s mortgage and mortgage-related CDO portfolios.” When you read news releases like this, you really don’t know whether to laugh, cry, or throw the telephone out the window. Fortunately, some smart investors had already seen the writing on the wall and had shorted the bond insurers’ shares.

Moody’s announcement followed by a few days the issuance by Ambac’s competitor, MBIA, of 14-percent AA-rated notes in a desperate attempt to salvage its AAA credit rating. At the time, the 14-percent coupon was 956 basis points higher than U.S. treasury notes of the same maturity, the rate that CCC-rated companies were paying at the time. Clearly there was a serious disconnect between what Moody’s was saying about the company’s credit rating and how the market was viewing MBIA’s financial prospects. Apparently 14 percent was the new AA interest rate for bond insurers that had chosen to enter the credit derivatives market to insure mortgage securities! MBIA was in serious straits, with exposure to bonds backed by mortgages and CDOs of $30.6 billion, including $8.14 billion of CDO-squareds (CDOs that own pieces of other CDOs). The death-knell for the bond insurers’ new business model was sounded.

The downfall of the bond insurers was a potentially catastrophic event for the Wall Street firms that were underwriting hundreds of billions of dollars of CDOs. These firms not only relied on Ambac and MBIA to insure the AAA-tranches of these deals, making them easier to sell to gullible buyers, but also counted on this insurance to protect themselves from losses on the huge amounts of this paper they couldn’t sell and ended up purchasing to get these underwritings done. Over the coming months, these firms would work with New York Insurance Commissioner Eric Dinallo and others to reduce their exposure to CDOs, and the bond insurers ultimately survived in wind-down mode. But another piece of the financial model that led the markets to the edge of the cliff was carried out in a body bag.

Taming the Beasts (Regulating Credit Derivatives)

Fortunately, events have proved that the financial system will not go the way of Jurassic Park, at least not yet. But the obvious question once the smoke cleared was how to regulate the credit default swap market and the rest of the derivatives market to avoid a repeat of 2008. Similar questions were raised in the commodities pits about commodities derivatives contracts, which were blamed for the spike in oil prices to over $140 per barrel in 2008 and the subsequent plunge to under $40 per barrel in the midst of the global financial crisis that followed. The fact that the credit default swap market grew to over $60 trillion in size and then pushed the global financial system to the brink of collapse ranks as one of the greatest regulatory failures of the modern financial era. The fact that regulators were cowed (or conned—pick your poison) by Wall Street into allowing credit default swaps to become the monster that ate Manhattan was inexcusable.

While credit default swaps have shrunk significantly in size since the financial crisis, they remain large enough to constitute a potential time bomb inside the financial system that could blow up any time. As long as naked swaps are allowed to be written, no firm is safe from a bear raid. A new approach to regulating these beasts is sorely needed. There are a number of practical solutions to the threat they pose. As noted previously, some respected investors like George Soros recommend outlawing credit default swaps unless the purchaser owns the underlying instrument being insured. Certainly a strong argument can be made that naked credit default swaps—those in which the derivative buyer or seller does not own an interest in the underlying instrument—should be barred. Opponents of such a ban argue that these instruments improve market liquidity for the underlying instruments, but practitioners will tell you that these arguments are dubious. Prior to the financial crisis, high yield corporate bond and bank loan market liquidity was already drying up due to the migration of trading from cash markets to derivatives markets. Large sums of capital had migrated away from cash markets into the derivatives market, making less capital available for trading the underlying instruments and significantly decreasing liquidity in those markets.

Since the crisis, overall market liquidity (both cash and derivative markets) has deteriorated further due to the advent of Dodd-Frank to the point where it is raising serious concerns about what will happen during the next serious market event. By 2015, dealers’ corporate bond inventories were down 70 percent from pre-crisis levels, rendering the high yield bond market less liquid than ever. The credit derivatives markets have also become significantly less liquid though still large enough to pose a systemic threat. Outstanding credit default swaps declined to roughly $20 trillion by the end of 2014 from over $60 trillion during the financial crisis. This is still large enough to dwarf the capital of the financial system. Furthermore, a number of firms that were active in this market announced in 2014 that they were exiting the market for single name and index credit default swaps.

The real arguments supporting naked credit default swaps are mercenary; these are opaque, difficult-to-price instruments from which Wall Street earns large profits. Wall Street is not a public utility—it is a profit-seeking engine whose primary purpose is to generate money for itself. The more complex and opaque the instrument, the easier it is for Wall Street to fool investors (even supposedly smart money investors like hedge funds and large institutions) and mark up these instruments to earn outsized profits from selling and trading them.

Proposals to regulate credit derivatives after the crisis generally focused on the following three areas:

- Requiring these instruments to be listed on an exchange.

- Monitoring counterparty risk.

- Increasing collateral requirements.

Listing these instruments on an exchange was intended to enhance transparency, while increasing collateral requirements was designed to limit speculation by forcing participants to have more skin in the game. While combining these measures with rules limiting financial institutions’ leverage may reduce systemic risk, they still leave unanswered the overriding policy question of whether society wants so much intellectual and financial capital devoted to speculation in naked credit default swaps and other non-productive activities. Banning such naked swaps could make capital available for more economically productive lending activities if the proper incentives (such as investment tax credits or accelerated depreciation deductions) were offered. While such a reform should be part of a far more comprehensive economic program, it points to the fact that if regulation were to limit opportunities for speculation, it might increase the chances that money could find its way into more productive activities.

Listing Credit Derivatives on an Exchange

Listing and trading credit default swaps on an exchange even with enhanced counterparty disclosure may be better than doing nothing, but falls short of what is needed to protect the financial system against another blow-up. In fact, plans to trade complex financial instruments on exchanges, which include provisions requiring enhanced counterparty disclosure, tends to distract policymakers from comprehensive solutions while allowing the powers on Wall Street to keep minting money at the expense of everyone else. The argument that this approach will improve transparency is a red herring since it relies on the ability of regulators and other non-specialists to decipher highly complex financial instruments. Giving these individuals greater access to information on credit default swaps is a far cry from handing them the tools to be able to understand them and the risks they pose. This is analogous to arguing that making quantum physics textbooks widely available will allow the average person to construct a nuclear power plant. The inspection staffs at the Securities and Exchange Commission and FINRA repeatedly demonstrate their inability to conduct competent inspections of firms engaged in far less complex investment schemes than those involving derivatives. How can we expect regulators to suddenly understand complex financial instruments without providing them with the necessary training to understand them? This is a highly dubious proposition. Greek is still Greek to somebody who only speaks English. Despite the best intentions, it is a virtual certainty that government work will never attract the type of talent necessary to untangle abuses that clever traders can construct in the credit derivatives area. Requiring these trades to be effected on an exchange simply passes the buck from legislators to regulators. And regulators will never be up to the task.

Furthermore, moving these instruments onto an exchange does nothing to eliminate the moral hazard regime whereby risks are socialized and gains are privatized. In fact, such a solution is likely to exacerbate the likelihood that such a regime will expand to new parts of the financial sector. Thus far, the “too big to fail” doctrine has been applied to institutions whose mistakes were deemed to pose a systemic risk. Moving credit default swaps onto an exchange would likely create the necessity for the government to protect these entities were the market to collapse due to a credit market meltdown. After all, these exchanges would stand at the center of the derivatives market and their failure pose a new threat to financial stability. Bailing out these exchanges might also provide protection for many institutions (i.e., members of the new derivatives exchange) that may not themselves be systemically vital, further extending the government safety net and moral hazard to places they do not belong.

Proponents of listing requirements argue that an exchange-based system will allow regulators and others to better track trading derivatives volumes and exposures and thereby better measure overall systemic risk. While having access to that information would be an improvement over the situation that existed prior to the financial crisis, it is questionable how useful such information will ultimately prove. The credit default swap market was $60 trillion in size at the time of the crisis, although that figure included many offsetting positions and the net exposure of financial institutions to these instruments was lower (again, nobody knew or knows the real figures). As of the end of 2014, this figure reportedly had shrunk to about $20 trillion as parties worked doggedly to reduce their exposures after seeing what happened to AIG, the bond insurers, numerous hedge funds, and others who drank the credit default swap Kool-Aid. But even at $20 trillion, the market is still vast and complex and filled with instruments that few if any of the regulators and senior executives charged with overseeing them understand. It may be helpful for regulators to have some idea of the total number of outstanding credit default swaps as a first step to figuring out how to regulate them. More likely, however, it will prove of limited utility since they still won’t understand what they are regulating.

Moreover, heavy lobbying by the financial industry limited the types of contracts that must be listed on exchanges to conventional or standard derivatives contracts. Nonstandard contracts and contracts used to hedge commercial business risks are still not required to be listed. As a result, efforts to move derivatives onto clearing houses have been only partially successful. As of July 17, 2015, for example, the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) reported that of the $257.4 trillion gross notional amount of interest rate swaps that it tracked, only 61.7 percent were traded on exchanges (leaving $98.5 trillion trading elsewhere). Of the $5.4 trillion of total credit default swaps it tracked as of that date, only 29.8 percent were traded on exchanges (leaving 70 percent or $3.8 trillion trading privately). If the idea was to capture all of derivatives in these exchanges, regulators were still far short of meeting their goals.15

Proponents for such exclusions argued, among other things, that such information is proprietary. This is another self-serving red herring that should be ignored. Steps can be taken to protect truly confidential information whose disclosure would be harmful to certain businesses.

Counterparty Surveillance

While simply listing derivatives on an exchange misses the mark, the goals of transparency and systemic stability would be much better served by requiring fuller public disclosure by the parties trading these instruments. As some observers, including this author, warned in the period leading up to the financial crisis, one of the most serious flaws in the credit derivatives regime was the inadequacy of counterparty risk monitoring. Not only did regulators and important market participants have no idea of who owed what to whom, but they had no real understanding whether the parties involved in credit default swap transactions were capable of meeting their obligations.

One of the most egregious examples of what can happen when parties fail to perform proper (or any) due diligence on their counterparties involved the Swiss banking giant UBS. UBS purchased $1.31 billion of credit insurance on the oxymoronically termed “super-senior tranche” of a subprime collateralized mortgage obligation (CMO) from a small Connecticut-based hedge fund, Paramax Capital, which had only $200 million of capital under management. Wisely unwilling to put all of its eggs in one basket, Paramax formed a special purpose entity to provide the credit insurance and capitalized it with only $4.6 million of its capital. The special purpose entity was subject to future capital calls if the value of the underlying CMO declined, which it inevitably did (this occurred in 2007), and ultimately Paramax defaulted after posting more than $30 million in collateral. Needless to say, when the hedge fund couldn’t make good on its obligation, UBS sued it, and naturally Paramax sued UBS back. If this transaction is typical of UBS’s business practices, it is little wonder that UBS announced on December 10, 2007 that it was taking a $10 billion write-down in the fourth quarter of 2007, most of it related to the type of super-senior instrument that it had somehow expected the diminutive Paramax to insure.16

Counterparty risk is separate and apart from the risk associated with the underlying debt instrument that is insured under a credit default swap agreement. It is a measure of whether the party selling the credit insurance will be capable of making good on its obligation. In order to properly evaluate counterparty risk, a party entering into a credit default swap contract needs to be able to analyze the financial condition of the other party to the transaction. This requires full disclosure of all of that party’s financial obligations, something that is an extremely tall order in today’s opaque financial world in which typical counterparties are involved in numerous balance-sheet and off-balance-sheet transactions of various degrees of complexity.

The odds of a typical counterparty being in a position to adequately measure this type of risk are extremely low. The current state of financial disclosure is inadequate to provide the type of information necessary to give counterparties the type of comfort they need to enter into these types of transactions. Reliance on financial institutions’ public financial statements or their credit ratings still leaves the system with insufficient information to evaluate counterparty risk on an institution-specific or system-wide basis. For a truly effective system to work, standards of disclosure must be significantly intensified and include provisions to protect confidential and proprietary information. Requiring parties to disclose such information could create a huge disincentive for many of them to engage in such transactions and could be an effective way of limiting speculative trading in these instruments. Increasingly opaque financial markets cannot leave the monitoring of counterparty risk in private hands; government must step in to enforce high standards of disclosure. We have already seen the results of leaving this responsibility in the hands of private sector regulators such as FINRA. Adequate disclosure would include not only counterparties’ complete financial condition (including all balance-sheet and off-balance-sheet obligations), and a complete listing of their derivative positions. While Dodd-Frank imposes significant reporting requirements on large hedge funds and other market participants that provide some of this transparency, it remains questionable whether the reams of information being disclosed can be meaningfully analyzed by regulators.

In the wake of the financial crisis, heightened disclosure requirements were greeted with howls of protest by hedge funds and other investors purporting to claim that their trading positions and strategies constituted trade secrets that need to be protected like matters of national security. These protests were properly dismissed for at least two reasons. First, regardless of what hedge fund operators like to claim, there is little that is proprietary about their positions or strategies. The only proprietary aspect of their operations is what occurs inside the heads of the funds’ managers, the thought processes that cannot be duplicated merely by viewing their positions. Moreover, in markets that operate on the basis of milliseconds, a disclosure regime that operates in arrears builds in a sufficient time delay to render this concern moot. Second, the vast majority of these hedge funds’ trades are speculative in nature; they are not increasing the productive capacity of the economy. Accordingly, the merits of disclosure in terms of enhancing systemic stability should outweigh any potential limitations on these funds’ profitability. Regulation should favor stability and productive investment over instability and speculation. The real challenge is that regulators are now in possession of so much information that it is questionable whether they are capable of analyzing it effectively.

Increasing Collateral Requirements

Higher collateral requirements come closer to the mark but still fall short of creating the type of economic incentives that would effectively discourage speculation. It was far too easy for speculators to manipulate the short-term borrowing rates of firms like Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers (and even Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley) through the credit default swap market in the midst of the financial crisis. Large investment banks or hedge funds could simply add these trades to their existing credit lines and mount bear raids on other firms in a completely unregulated environment.

The real question comes back to the type of instrument represented by a credit default swap. These are insurance contracts that, in the case of naked swaps, do not require the party purchasing the insurance to own an insured interest. As a result, their economic interest in the outcome of the trade remains limited and their incentive to see companies fail remains high; increasing collateral requirements does little to change either of these conditions. Limited liability provides enormous incentives for investors to speculate and is another aspect of the moral hazard problem that haunts the U.S. financial system. Increasing collateral requirements in the absence of requiring an insurable interest in credit default swaps will do little to stem the type of speculation that contributed to the 2008 financial crisis. At best, such a regime will force some weak hands out of the market.

At the end of the day, it is difficult to escape the conclusion that anything less than an outright ban on naked credit default swaps will accomplish the goal of directing more financial and intellectual capital into productive rather than speculative uses while improving systemic transparency and stability. The advent of credit default swaps has done little to improve liquidity in underlying cash markets; in fact, it has produced the opposite effect as trading capital has migrated out of those markets and into the derivatives markets.17 Moreover, the types of perverse incentives these instruments create to see companies fail rather than succeed suggest that the system could do with fewer of them. Requiring purchasers of credit insurance to have an insurable interest in the underlying debt instrument would be the surest way of addressing the most significant regulatory challenges they pose.

One of the arguments in favor of naked swaps is the same argument in favor of naked short-selling of stocks. Proponents argue that such a strategy imposes an important discipline on companies and provides an incentive for them to maintain strong credit quality. But as George Soros has pointed out, credit default swaps work in a completely different manner than selling stocks short.18 When an investor is short a stock, an increase in the stock price raises his exposure and renders it increasingly expensive to maintain the position. Moreover, the margin rules require the short-seller to post additional collateral to hold the position (although short positions effected through options and other derivatives can minimize margin requirements). These pressures discourage short-selling.

Credit default swaps do not discourage short-selling because they offer limited risk and unlimited reward. An investor who wants to short a credit can purchase a credit default swap for a fixed amount of money and limit his exposure to that amount of money. As that credit deteriorates, the value of his swap increases and he does not have to post additional collateral (and may, depending on his agreement with his lender, be able to withdraw collateral). This encourages the short-selling of credit. Taking the other side of this trade is much less attractive (that is, selling the credit insurance) because the seller of insurance must continue to post additional collateral as the underlying credit deteriorates. The asymmetry between selling insurance (going long) and buying insurance (going short) can encourage short-selling and introduce a significant short bias into the marketplace. This is far different from imposing an honest discipline on companies to improve their balance sheets and maintain strong credit quality. Instead, credit default swaps introduce a strong incentive to speculate on the short side, which is hardly conducive to directing capital to productive economic uses. The structure of credit default swaps therefore renders them far more destabilizing to markets than other types of hedging instruments and bolsters the case for limiting their usage to situations in which the buyer owns the underlying debt.

❊❊❊

There is another wonderful scene in Jurassic Park when the scientists are touring the laboratory where the dinosaurs are bred. One of the scientists tries to explain to Dr. Malcolm that the park has bred only female velociraptors, a particularly dangerous breed of dinosaurs that come to wreak their own special havoc throughout the film (and its many sequels). Dr. Malcolm responds that it isn’t possible to limit the breeding to females, and the scientist condescendingly explains that it’s really a rather simple matter of excluding a male hormone from the genetic mix. Dr. Malcolm disagrees and simply says, “Life finds a way.” The same is true of Wall Street when it comes to regulation. Wall Street will find a way to manipulate its way around restrictions placed on its ability to create new products and generate profits regardless of the systemic risks its behavior poses.

One of the methods that institutions have employed to avoid restrictions on their derivatives operations since the crisis has been to shift derivatives trades to overseas affiliates, primarily those in London that are no longer guaranteed by their U.S. parent or alternatively to revoke guarantees on specific transactions. In June 2015, the CFTC finally approved a proposal to close this loophole and require the offshore units of U.S. institutions to adhere to CFTC rules even when they are not explicitly on the hook for the trades. As this book was going to press, the proposed rule was still subject to comments and has to be voted on a second time to go into effect. The constant cat-and-mouse game between regulators and traders is an age-old competition that will continue as long as there are markets. That is why it is incumbent upon every individual and institution that is affected by what occurs in the financial markets to not only understand derivatives but to appreciate why they can’t be allowed to run wild like dinosaurs in a china shop.