CHAPTER 9

Finance after Armageddon

For many men and women who spent their professional lives on Wall Street, the year 2008 felt like Armageddon. Not only did many of them lose their jobs, but they also lost the wealth and financial security they spent decades accumulating. Regulators and others in the seats of government surely felt as though they were facing the end-of-days when confronted with the death of capital. The global financial system was virtually paralyzed in September and October of 2009, and unimaginable measures were taken to resuscitate it.

The financial crisis was nearly an extinction-level event. Anybody who believed that the system could continue without drastic reform afterward was probably beyond convincing or stood to profit too much personally from maintaining the status quo. Each succeeding financial crisis of the last three decades was more severe than the last because the underlying imbalances that caused it were growing exponentially, distorting the economy more profoundly and becoming less susceptible to correction without inflicting severe hardship on significant parts of society. After each of the previous crises, serious financial reform was sloughed off and the reins on risk-taking were further loosened in the name of free markets. For example, conduct that increased systemic instability, such as the creation of off-balance-sheet entities to conceal debt, continued to receive favorable treatment under bank capital rules even after the abuse of such entities by Enron Corp. caused a crisis of confidence in 2001 that inflicted serious damage on the markets. Increasing tolerance for behavior that escalated systemic risk created a system characterized by extreme moral hazard in which gains are privatized in the hands of a small elite while losses are socialized among the effectively disenfranchised and overburdened American taxpayer. American economics had become little more than socialism for the rich and capitalism for the poor.

For those who still believed that capital can be a force for good in the world if wisely managed and regulated, the financial crisis created an opportunity for serious discussion about what could be changed within the limitations of a corrupt political system and a financial-political complex that exercises power over all aspects of society. The time was long overdue for a serious call-to-arms to reform a system that has the capability of doing great good but has inflicted great harm by being repeatedly diverted into wasting its resources on leverage and speculation.

Despite the profound crisis that capitalism experienced in 2008, serious discussion of reform was quickly sidelined by powerful lobbying interests. After markets hit their nadir in March 2009, a veneer of stability returned to the financial world. But below the surface, serious instabilities continued to boil. Seven years later, as the United States prepares to elect its first new post-crisis president, the enormous mountains of debt that were created to triage the global economy are weighing down sovereign balance sheets and limiting governments’ ability to deal with future challenges before they lurch into a new crisis. At the same time, despite the massive shift of debt from the private to the public sector, corporate balance sheets in the U.S. are significantly more leveraged than before the financial crisis. Low interest rates disguise the negative effects of increased leverage, but the global economy is feeling the strain in terms of slower growth. The weakened condition of the global system renders reform more urgent than ever.

Regulatory reform must be approached within the context of the consequences of what economic instability really means and what it can lead to. This requires a much greater focus on the long-term consequences of failing to act rather than concerning ourselves exclusively with reacting to short-term emergencies. The failure of a single institution is, in the long run, a relatively minor event. The system and its constituent parts will find a way to survive. But the long-term consequences of rescuing every poorly managed firm are extremely negative because of the moral hazard they create in a system that has grown accustomed to seeing risk socialized and profit privatized.

In order to develop long-term solutions to the problem of financial stability, one must learn to think in terms of the arc of history. Modern markets and media have shortened our attention spans to the point where historical consciousness has been all but obliterated, and it requires a special effort to focus on anything beyond the immediate moment. Despite the urgent necessity to remember the past and learn from it, people today have forgotten how to think historically. As the social and literary critic Frederic Jameson has written, people need “to think the present historically in an age that has forgotten to think historically in the first place.”1 This is particularly imperative at junctures when it feels like the center cannot hold, periods in which prior assumptions fail us and new answers are needed.

And what better place to start thinking about the consequences of Armageddon than to return to the gates of the place where barbarism last reigned when humanity failed us? After all, in 2015 the forces of barbarism are raging again in the Middle East and Eastern Europe and, due to our lack of vigilance, are spilling blood in the streets of Western cities as well. In 1969, Theodor Adorno called for an uncompromising standard for education that should be applied more widely to all areas of human endeavor:

The premier demand upon all education is that Auschwitz not happen again. Its priority before any other requirement is such that I believe I need not and should not justify it. I cannot understand why it has been given so little concern until now. To justify it would be monstrous in the face of the monstrosity that took place. Yet the fact that one is so barely conscious of this demand and the questions that it raises shows that the monstrosity has not penetrated people’s minds deeply, itself a symptom of the continuing potential for its recurrence as far as peoples’ conscious and unconscious is concerned. Every debate about the ideals of education is trivial and inconsequential compared to this single ideal: never again Auschwitz. It was the barbarism all education strives against.2

Some readers may view it as alarmist to compare the obligation to prevent genocide from reoccurring to the obligation to maintain stable financial markets. But such a connection is absolutely necessary. It is blindness to such comparisons that leads to barbarism, and the conditions that led to the monstrosities that occurred in Germany 70 years ago are no less present in our world today. Just ask the people fleeing ISIS in the streets of Paris or San Bernardino or the barrel bombs of Bashar al-Assad or Vladimir Putin’s forces in the Ukraine. This isn’t happening by accident; it is a direct result of the failure of America to stand up to tyrants and to enforce high standards of conduct at home and abroad. Because we fail to imagine the worst, we are unprepared to deal with the worst when it descends upon us. The world keeps teaching us that, if only we are willing to pay attention.

Adorno also wrote in the same essay quoted above: “[a]mong the insights of Freud that truly extend even into culture and sociology, one of the most profound seems to be that civilization itself produces anti-civilization and increasingly enforces it.” Nearly four decades after Adorno’s warning, insufficient attention is paid to the fact that without functioning financial markets that are capable of raising capital for productive uses and creating opportunity for the disenfranchised, the world is far more likely to spin into anarchy. We are already seeing that happen in the Middle East, Eastern Europe, and Africa. The economic grievances that led to Nazism’s vicious rise to power in the 1930s are echoed in similar complaints around the world today. Having exported economic disaster to all corners of the world in the 2000s and then laid down in the 2010s while our enemies run roughshod over our interests around the world, the United States and its allies need to reorder their moral and strategic priorities as they heal their economies in order to create a more equitable and stable global order.

As the tools of finance become more sophisticated, the obligation to regulate them prudentially increases exponentially. With great power comes great responsibility. This is the reverse of the Obama doctrine, which believes that with great power comes no responsibility, but it is the only doctrine befitting a still great power like the United States.

In Modernity and the Holocaust (1991), the sociologist Zygmunt Bauman argued that two of modernity’s signal achievements made the holocaust possible: technology and bureaucracy.3 In fact, he argues that the genocide of the Jews (and murder of millions of others) was carried out in a manner that was completely consistent with the norms of how business was conducted at the time. In other words, Auschwitz was an example of modernity cannibalizing itself. Why shouldn’t the same be said about modern finance and the succession of increasingly destabilizing financial crises that damaged the financial markets over the past two decades? Beginning with portfolio insurance, which contributed to the stock market crash of 1987, and continuing through credit default swaps, which swept away some of the world’s largest financial institutions in 2008, financial technology itself was the tool that almost destroyed the very system it was designed to protect from risk. What could be a better example of Adorno’s “civilization creating anticivilization?” And if it is indeed the case that our most advanced tools are also the ones most capable of destroying us, mustn’t we better educate ourselves to prevent that from happening? As the perpetrators of the crisis try to sneak away from the scene of their crimes unseen, it is incumbent upon the rest of us to ensure that the intellectual and moral lapses that caused so much damage are exposed for what they are. Only after their errors and crimes are exposed can they be disposed of.

Yet Congress fiddles while Rome burns, cheered on by special interests that serve to benefit from the status quo. Proposals for reform were derailed and diluted by Wall Street interests that want us to forget that 2008 even happened. According to the Center for Responsive Economics, the finance, insurance, and real estate industries spent $223 million on lobbying in the first half of 2009, a period in which these very institutions were still in serious financial distress and could have used that money to bolster their weakened balance sheets.4 Nobody should be fooled. The enemies of reform are not just enemies of reform; they are enemies of a more just and fair society in which the rewards of capital are shared rather than slopped up by a small elite like pigs gorging out at a feeding trough. Reform must start from within and it must begin now.

It is almost impossible to overstate the urgency of financial reform if we are to avoid the social and political consequences of severe economic instability. Maintaining stable and equitable financial markets is not just an economic but a strategic and moral imperative. The status quo, and any system that resembles it, is certain to lead the world into further cycles of boom and bust that will exceed the abilities of both markets and governments to repair. As our readings of Smith, Marx, Keynes, and Minsky suggest, and as our historical experience demonstrates, boom-and-bust cycles are deeply embedded in the nature of capitalism. While some may argue that the authorities effectively prevented a wholesale collapse of global finance in 2008, the need to maintain unprecedented policies long after the crisis passed is prima facie evidence that their policies are seriously deficient. The fact that financial markets suffer from imbalances of such extremity that they not only nearly collapsed in 2008 but years later still suffer from sluggish growth and terminal debt problems illustrates that the system requires radical reform. In 2008, the markets were not remotely capable of fixing themselves, and governments managed to return the system to stability by employing temporary fixes.

The unprecedented measures governments were forced to take in 2008 imposed long-term destabilizing effects on the global economy. Those actions were not permanent solutions to the economic imbalances that led to crisis; they were merely temporary bandages applied to triage the patient. They did not create the conditions necessary for sustainable economic growth; all they did was treat a debt problem by creating more debt. The post-crisis period wasn’t the first time that underlying imbalances that caused a crisis were left unresolved. In fact, they followed the pattern of the last three decades where one crisis after another caused by flawed monetary and fiscal policy was addressed by short-term fixes that left underlying imbalances unresolved. The imbalances kept growing and distorting the global economy beyond any chance of returning to equilibrium. In 2016, the result is $200 trillion of global debt that is suffocating economic growth and can never be repaid. This is a road to ruin rather than rebirth.

There is a further reason why the financial system desperately needs to be reformed to minimize the chances of future crises. Emergencies give government license to flout the rule of law. The death of capital can lead to the death of liberty and human rights, which is another reason why the moral obliquity of financiers who contribute to serial financial meltdowns is so reprehensible. Their conduct is not only wrong in itself, but because it tempts the government to abuse its power. Each time there is a financial crisis, the SEC and Justice Department throw out the rule of law at the behest of politicians seeking to divert attention from their own mistakes. As each financial crisis grows in severity, this type of post hoc criminalization of finance becomes a greater threat to our liberty. While privileged individuals who bleed the system for their own benefit deserve no special pleading, it remains incumbent on the government in a crisis to respect the rule of law. Unfortunately, all too often it does the opposite. Government by show trial should be associated with a gulag, not a republic.

The steps taken to address the 2008 crisis were in many ways a natural extension of the government’s conduct after the 9-11 attacks. The passage of the Patriot Act had already seriously weakened civil liberties by giving law enforcement powers to do virtually anything it deemed necessary in order to protect the country from potential terrorist attacks. This came to include such questionable practices as warrantless wiretapping of U.S. citizens, the practice of “extraordinary renditions,” the suspension of habeas corpus, and the torture of suspected terrorists (and these are only the practices we know about). The financial crisis of 2008 threatened such extreme economic and social chaos that the Obama administration took it upon itself to ignore the rule of law by abrogating the bankruptcy laws in the General Motors and Chrysler bankruptcies. It then used questionable measures to pass ObamaCare, make dubious recess appointments to the National Labor Relations Board (which the Supreme Court later deemed illegal), pass an illegal nuclear arms deal with Iran, and to push through countless executive orders of questionable legality. An administration that demonstrated an early proclivity to exercise raw power in the name of crisis management fell into the regular habit of ignoring the Constitution and other laws in the face of toothless Republican opposition. The most effective way to limit the government’s opportunity to rob us of our freedom in the future is to minimize the potential for future crises to occur in the first place.

By the time the economic imbalances being created today come home to roost, it will be too late to introduce the reforms necessary to strengthen institutions to withstand the coming storms and the increasingly draconian measures the government will feel licensed to take to deal with them. Accordingly, meaningful financial reform must be instituted as soon as possible to prepare the system for the instability that is certain to come when everyone least expects it (for that is what instability is, a disruption that occurs when the system is least prepared to handle it). A well-fortified and stable system will be the best protection against government again overstepping the bounds of law to manage the next crisis.

The consequences of failing to act are not theoretical. On a global basis, they include a widening gap between rich and poor, high levels of hunger and poverty not only in disenfranchised areas of the world but here at home, ecological devastation, and political instability. On a national level in the United States, the effects include the ruination of neighborhoods and communities through poverty and violence, sustained high levels of unemployment (particularly among youths and minorities), widening wealth inequality, increasing political divisiveness, and a seriously deteriorating fiscal situation. Despite all the advances that mankind is making in science and technology, there is much more work to do to fulfill even our most modest obligations to billions of people around the world. We will not have even the smallest chance of doing so without a stable financial system. Only a strong and prudently regulated global financial system whose benefits are shared equitably will be able to effectively meet the challenges posed by future threats. We do not have such a system today, and we certainly did not have one leading into the financial crisis. Instead, the system encouraged speculation at the expense of production, debt at the expense of equity, and short-term gain at the expense of long-term investment. True financial reform must be designed to reverse these priorities in order to prevent capital from dying again.

Obama Goes to Wall Street

In September 2009, on the first anniversary of the day Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy, President Barack Obama flew Marine One up from Washington, D.C. to make a lunchtime speech at Federal Hall on Wall Street to discuss financial reform. By this time, much of Wall Street (or what remained of it after 2008) had already returned to the practices that contributed to the financial crisis: exorbitant, asymmetric compensation schemes; trafficking in highly complex and highly leveraged credit derivatives; and the issuance of record levels of debt, including debt associated with leveraged buyouts and other speculative forms of investment. By mid-September 2009, it was obvious to many observers that the battle for meaningful financial reform had already been lost.

The president’s speech repeated proposals contained in a white paper authored by Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner and the director of the National Economic Council Lawrence Summers that was released on June 14, 2009, entitled “Financial Regulatory Reform: A New Foundation.” President Obama brought all of his considerable oratory skills to bear on his audience that day, a group that included many of the most influential legislators in the financial arena as well as key representatives from the largest financial institutions and hedge funds. His message was blunt: “We will not go back to the days of reckless behavior and unchecked excess that was at the heart of this crisis, where too many were motivated only by the appetite for quick kills and bloated bonuses,” he warned his audience. “Those on Wall Street cannot resume taking risks without regard for consequences and expect that next time, American taxpayers will be there to break their fall.” To say that Obama’s plea fell flat, however, would be an understatement. His words were largely greeted with silence, according to The New York Times reporter Andrew Ross Sorkin,5 who was in the audience. Most of the financial executives in attendance were trying to position the traumas of 2008 as ancient history and were actively lobbying the government to allow them to go back to their old ways. The model of socializing risk and privatizing gain had worked exceedingly well for the financial elite sitting in Federal Hall that day while impoverishing significant portions of the general population and weakening the economic fabric of the United States. This audience was not interested in changing the status quo. And as it turned out, Mr. Obama lacked the political will and leadership skills to back up his fancy rhetoric.

The sad truth was that the reform train had left the station a long time ago. While just one year earlier the entire financial system was staring into the abyss, trillions of dollars of intervention from the U.S., European, and Chinese governments had created the illusion that all was well with the world economy. Credit markets were functioning again; the stock market had risen approximately 50 percent from its March 2009 lows of 666 on the S&P 500 and 6,547 on the Dow Jones Industrial Average; and many Wall Street firms had repaid the government money they had taken (or been forced to take) in late 2008 and were now focusing on how to overpay their employees once again. While Wall Street firms were not as leveraged as they were before the crisis, they were again taking outsized risks with their balance sheets. And while there were competing legislative proposals before Congress regarding how to overhaul financial regulation, the old set of laws was still in place with diminishing prospects for meaningful change.

A year after the death of capital, comprehensive regulatory reform of the type needed to truly stabilize the financial system was all but dead. There were some small signs of progress, such as potentially aggressive actions taken by the Federal Reserve and Treasury Department on compensation reform and by the SEC on dark pools. But on more systemically serious matters such as derivatives legislation and monetary policy management, there was little sign that serious change would be effected. This was profoundly disappointing because future financial instability, which is a certainty, rendered radical regulatory reform an urgent necessity.

Principles of Reform

Regulatory reform must be comprehensive in nature in order to maximize financial stability. Earlier in this book, I proposed specific reforms with respect to two areas that have contributed to the overall instability of the economic system—private equity (see Chapter 6) and derivatives (see Chapter 7). On a broader basis, six key areas must be addressed in order to provide a proper foundation for a more stable financial system that would no longer reward speculation at the expense of productive investment or socialize risk and privatize profit:

- Taxing speculation.

- Creating a unified regulator.

- Addressing the “too big to fail” doctrine.

- Improving the capital adequacy of financial institutions.

- Reforming monetary policy management.

- Improving systemic transparency.

Each of these areas is highly complex and requires a comprehensive approach. The complexity of the modern financial system is the major challenge of financial reform, but one that can be overcome by thoughtful and patient legislation. Partial solutions will leave too much room for abuse and the return of instability. A reform program must integrate all of the principles enunciated above in order to be effective.

The current regulatory system is based on the assumption that markets are efficient and investors are rational. Accordingly, regulation was designed to minimize governmental interference with the efficient and rational operation of markets. (Not to put too fine a point on it, but that is a polite way of saying, “garbage in, garbage out.”) Those who warn that markets are obviously inefficient and investors far from rational beings are largely marginalized in terms of influencing policy. That is unfortunate, because markets consistently demonstrate their inefficiency, and investors repeatedly exhibit their irrationality. Regulatory reform must start from the premise that markets are inefficient and investors are irrational.6 Our society should not have to continue to pay such a high price for clinging to beliefs that are consistently shown to be false. Working with any other set of assumptions will lead reform down the wrong path.

The election of Barack Obama offered some promise that things would change, but his choice of Timothy Geithner as treasury secretary, Lawrence Summers as his top economic advisor, and Mary Schapiro as head of the SEC were signs that little would change. These failed stewards of the status quo were the least likely individuals to deliver meaningful reform. Truly comprehensive and meaningful change requires the raw power of new ideas and the political courage to put them into effect rather than reshuffling the same tired old faces through the revolving door.

If financial reform is going to be effective, it must address the two most profound flaws that currently plague Western capitalism. The first is the phenomenon discussed throughout this book—the predominance of speculative over productive investment. This issue has been addressed with far more forthrightness in the United Kingdom than in the United States, where Britain’s chief financial regulator, Adair Turner, raised the ire of bankers and other members of the financial services establishment by publicly questioning the purpose of much of the activity in modern finance. In September 2009, Turner told a group of financiers at a dinner held at Mansion House, the grand residence of the Lord Mayor of London, that banks “need to be willing, like the regulator, to recognize that there are some profitable activities so unlikely to have a social benefit, direct or indirect, that they should voluntarily walk away from them.”7 While honest observers welcome such outspokenness, this message was greeted with a fair degree of disdain by the audience. But Turner, who in March 2009 authored “The Turner Review,” a fairly scathing report on the financial crisis, is on to something. The global economy simply cannot sustain a regime in which increasing amounts of capital are devoted to churning money out of money rather than adding to the productive stock of the world. Banks in particular, but other financial institutions as well, especially those that operate under the aegis of government licensure that gives them certain rights that non-licensed businesses do not enjoy, possess a public utility function that was thrown to the wayside in recent years by the obsession with free markets. It is time to restore some balance to these institutions to ensure that society is not completely sacrificed at the altar of the profit motive.8

The second flaw is the model that socializes risk and privatizes reward. This model is not only economically defective because it places an undue burden on governments and the taxpayers that fund them, but is morally retrograde in absolving individuals of responsibility for their actions, imposing the highest costs on those least responsible for harming society. This regime also widens the gulf between rich and poor and exacerbates social instability.

The basic premise of any regulatory regime must be that it creates the proper incentives that favor productive investment over speculation and more fairly distributes economic gains and losses among the populace. Society must come to understand that the way investors generate profits is just as important as the amount of profits they generate. This is why human beings were vested with moral sentiments—so they could distinguish the quality of human conduct from the quantity of what that conduct produces. And only by appreciating the quality of economic output as well as its quantity will society be able to increase productive investment and improve the quality of life for all of its citizens.

Impose a Tax on Speculation

Toward the end of 2009, proposals were floated in Congress to impose a modest tax on certain types of securities transactions. One proposed piece of legislation, titled “Let Wall Street Pay for the Restoration of Main Street,” would have imposed a 0.25 percent tax on the sale and purchase of stocks, options, derivatives, and futures contracts. Wall Street is unalterably opposed to any such tax, but it is a good idea for a number of reasons:

- Tax policy should be used to create the proper types of economic incentives, and to discourage types of behavior that damage the economic system and society at large. One of the indisputable lessons of the 2008 financial crisis is that far too much capital is being devoted to speculation and far too little is being channeled to productive investments. Increasing the cost of speculation is a logical and economically efficient way of discouraging unproductive activities.

- The U.S. government is running unsustainable deficits and is desperately in need of revenues. In addition to ending egregious tax breaks for financial interests such as the “carried interest tax” on private equity profits and permitting hedge fund billionaires to defer their taxes for periods of as long as 10 years (a boondoggle that was finally terminated), the government should be raising revenue from socially unproductive activities. The financial industry can easily afford to pay a tax on its speculative activities. Moreover, a significant amount of securities trading today is not for the purpose of providing growth capital for corporations but is merely done to churn financial profits. By 2015, approximately 75 percent of daily trading activity had nothing to do with fundamental investing but was instead tied to high frequency trading and ETF trading strategies that contribute little to capital formation or the productive capacity of the economy. Accordingly, a tax on these activities would be a perfectly reasonable and economically harmless way to raise revenues.

Transactions such as credit default swaps and leveraged buyouts and recapitalizations have extremely wide profit margins built into them by Wall Street dealers and can easily bear the type of tax proposed here. As someone who has worked in these markets for more than two decades, I can assure readers that Wall Street arguments to the contrary are both self-serving and false. One of the points of such a tax would be to make Wall Street firms and their clients think twice about engaging in speculative activities that contribute nothing positive to society, and force them to give something back economically if they are hell-bent on engaging in such activities.

Rather than a flat 0.25 percent tax on securities trading, I would propose a sliding scale tax rate applied to the face amount of the following types of transactions:

- Naked credit default swaps if they are not banned entirely (1.25 percent tax).

- Debt and preferred stock issued in leveraged buyouts, leveraged recapitalizations, or debt financings used to pay dividends to leveraged buyout sponsors (0.60 percent).

- Quantitative trading strategies (0.35 percent).

- Equity derivatives (options, futures contracts) (0.25 percent).

- Large block trades (0.25 percent).

- All other stock, bond, and bank loan trades (0.15 percent).

Coupled with other measures aimed at reducing systemic risk (i.e., increasing capital adequacy at financial institutions, increasing collateral requirements, and imposing listing requirements for credit default swap trades, and so on), such a tax would impose a cost on activities that add little in the way of productive capacity to the economy and increase systemic instability. Obviously any such tax would have to include provisions to prevent forum shopping so investors and traders could not avoid the tax by moving their activities abroad. Such a tax regime would also contribute to the progressivity of our tax system by asking those who benefit the most from our economy to pay a little more in the way of taxes. The tax should not be imposed on stock, bond, and bank loan investments in retirement accounts under $1 million in size (IRAs, 401ks, etc.).9

End Balkanized Regulation

One aspect of the current regulatory regime that must be reformed in order to fortify systemic stability is its balkanized structure. The current regulatory system must be replaced with a unified system. Whatever the historical and political sources of the existing multiple (and often conflicting) agencies that regulate the financial industry (the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Commodities Futures Trading Corporation, FINRA, state banking and insurance regulators, and the Federal Reserve), this structure has been rendered archaic by changes in markets and financial technology. In a world where all financial instruments can be deconstructed into 1s and 0s, effectively erasing the barriers among insurance, banking, securities, and real estate firms and rendering any one of them capable of creating systemic risk, the existing regulatory regime is a surefire recipe for disaster. There is no longer a rationale for regulating securities firms, commercial banks, and commodities firms from separate federal agency silos while leaving states to regulate mortgage brokers and insurance companies. Instead, a single regulatory body should assume responsibility for overall regulation of the financial industry and then form separate sub-agencies to regulate each separate type of firm. In a networked global economy, all of these industries are closely linked (for instance, they all trade with each other as counterparties) and must be regulated at the federal level by a unified regulatory body that is guided by the principles of regulation discussed here—encouraging production over speculation, transparency over opacity, and stability over instability.

Moreover, a single, independent regulatory body is needed to monitor and regulate systemic risk. The Federal Reserve has been touted by some observers (and by its own chair) as the most qualified candidate for the role of super-regulator. Such a choice would be unwise for several reasons.

First and foremost, the central bank’s track record in managing monetary policy is nothing short of disastrous. Despite the fact that monetary policy is almost impossible to get just right, the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy methodology is a case study in pro-cyclicality, is based on deeply flawed intellectual premises, and has placed the U.S. economy on an unsustainable path of speculation and indebtedness. A central bank that sat idly by while obvious bubbles built up and burst hardly seems qualified to prevent the same thing from happening in the future.10 This track record alone renders the institution a poor choice to serve as the party responsible for monitoring the very systemic risk its own policies consistently exacerbate.

Furthermore, the Federal Reserve’s own practices set a poor example of the type of transparency that the system requires to improve stability. It is frankly anachronistic that the central bank refuses to issue real-time releases of the minutes of the Open Market Committee meetings, and instead discloses this information only after significant time delays that leave the markets guessing as to the thinking of the most powerful monetary regulator in the world. In a day and age when information travels around the globe in the blink of an eye, and markets uncover information with astounding speed, the attempt to delay disclosure of the central bank’s deliberations borders on absurdity (and antiquity). Moreover, the central bank needs to make a greater effort to make its operations understandable to laymen rather than to economists and market experts. Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen have been far more constructive in this respect than their predecessor Alan Greenspan, who never met a sentence he couldn’t mangle whenever he testified before Congress or otherwise spoke publicly. The decision-making of the Federal Reserve should not be a state secret—it should be a process subject to public scrutiny and debate. That does not mean that the Federal Reserve should lose its independence; one can only imagine the damage that would be done to the economy if monetary policy were subject to more direct influence by Congress, which demonstrates with every passing year its inability to manage complex long-term economic issues with any degree of foresight and responsibility. But the system needs an independent risk monitor that will lead by example, and the Federal Reserve is not that body. Instead, an independent nonpartisan oversight board should be appointed to fill such a role.

Too Big to Fail

In the wake of passage of Dodd-Frank stand a smaller number of “too big to fail” institutions sitting on top of a powder keg of hundreds of trillions of dollars of derivatives contracts. Instead of reducing the threats posed by these institutions, post-crisis reforms concentrated them in fewer hands. While Dodd-Frank established wind-down procedures to deal with the failure of large financial institutions, it failed to effectively address one of the key factors that could cause them to fail in the first place: undue concentrations of derivatives on their balance sheets, a topic addressed elsewhere in this book.

The 2008 financial crisis taught the world a valuable lesson: Institutions that are too big to fail are equivalent to government protectorates. Or put another way, only the government is too big to fail, so any institution that is too big to fail must be taken over by the government. The regime that was in place before the crisis privatized these institutions’ profits before they ran into trouble and then, when they hit the skids, socialized their losses. That is unacceptable. Only the government should be considered too big to fail, and, frankly, if the United States continues on its current fiscal and monetary path, that belief will be tested as well. But the concept of permitting private institutions to grow sufficiently large to pose systemic risk in a system that privatizes their profits but socializes their losses must end. As a practical matter, there is little prospect that the government is going to break up JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, or any other firm whose failure would pose systemic risk. Accordingly, we must accept the reality that there are institutions that are too big to fail but must also impose a regime that requires a bailout of such firms to result in government ownership so that the American taxpayers can share in both the gains and the losses of the enterprise, rather than limiting the gains to insiders and shifting the losses to outsiders.

There are currently several institutions whose failure could pose a serious systemic risk. In one category are institutions that are already owned by the U.S. government like Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and others that were owned by the government and returned to private ownership like Citigroup and AIG. Then there are other institutions like JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, Goldman Sachs Group, Inc., Bank of America, Morgan Stanley, and several major insurance companies that are not owned by the government whose demise, while currently unlikely, would cause severe systemic stress. Nonetheless, the collapse of some members of this latter group of firms is not impossible, particularly without meaningful reform of derivatives The combination of lowering balance sheet leverage, reducing the risk embedded in asymmetric compensation schemes, and improving transparency through the elimination of structured investment vehicles (SIVs) have been important steps in minimizing the possibility that a single large firm could destabilize the financial system.

Nonetheless, systemically important firms have a special dual role in the economy and in society. They are not simply profit generators; their size and reach effectively render them public utilities whose continued health is vital to the continued viability of the economy. They have gained that status in part through government licensure, which should be considered a privilege rather than a one-way grant of a right to print private profits. The best approach to the too-big-to-fail doctrine is one that ensures that gains and losses are properly allocated among different societal constituencies. Merely limiting the size of an institution will not ensure that result.

Accordingly, there must first be a regime under which large institutions are regulated to minimize the risk that they will suffer large losses that can place them—and therefore the system—at risk. Such a regime would address issues such as capital adequacy, vulnerability to financial products of mass destruction such as naked credit default swaps and other derivatives, and the imposition of countercyclical approaches to balance sheet management. Secondarily, the system must no longer be designed to address failures, which are inevitable in any capitalist economy, by socializing the losses and privatizing the gains. This would entail reforming compensation practices to better align executive rewards with risk, as well as providing the government with an ownership stake in businesses that have to be bailed out. The fact that the U.S. government profited from its investment in Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and other companies that received TARP funds was entirely appropriate. It is also why it would be inappropriate to reward shareholders of Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, or AIG that brought lawsuits claiming that the government unlawfully deprived them of their property when it stepped in to rescue those companies. Had the government not bailed out these three companies, their stockholders would have been wiped out. The only reason stockholders are able to conjure up any claim today is because the government did not want to consolidate those companies’ trillions of dollars of debt on its own balance sheet, which is a technical matter that should not lead to unjust enrichment of opportunistic investors. If we want to have an ownership society, gains and losses have to be shared more equitably than they were after the financial crisis.

Improving Capital Adequacy

One of the lessons of the 2008 crisis is that financial institutions rarely have sufficient capital cushions to sustain themselves through true market calamities or even severe economic downturns. Financial institution shareholders demand high returns on equity to boost the value of their stockholdings, particularly where employees own large amounts of stock. Unfortunately, such demands conflict with sound balance sheet practices and lead to excessive leverage and other reckless management behavior. One of the frustrating characteristics of capital is that it is most available when least needed, and least available when most desperately needed. Policy must be changed to ensure that financial institutions are required to maintain stronger balance sheets in prosperous times, even if this reduces their return on equity and lowers their stock prices. In the end, this will reduce the volatility of their stock prices and reduce their odds of failure.

Limiting Banks’ Balance Sheet Leverage

Important steps were taken after the crisis to reduce the balance sheet leverage of commercial and investment banks from the dangerously high levels that contributed to the financial crisis. Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers both sported leverage ratios of more than 30-to-1 when they failed in 2008, a direct result of the loosening of their net capital rules in August 2004. These levels did not include the off-balance-sheet leverage that these firms were concealing from regulators and investors. Such high leverage was the financial equivalent of playing Russian roulette with five of the six chambers of the gun loaded. Once the off-balance-sheet leverage with legal or reputational recourse to the sponsoring institution was added, it was the equivalent of placing a bullet in the sixth chamber. Less than a 3 percent drop in the value of these firms’ assets was sufficient to wipe out their equity. Such a thin cushion was insufficient for a traditional bank and was woefully inadequate for investment banks whose business models were based on proprietary trading and trafficking in highly complex financial instruments whose liquidity (and value) could (and did) suddenly evaporate.

Today, most of the large commercial banks and investment banks have reduced their leverage ratios significantly below where they were when the crisis began. Both Dodd-Frank and the second set of banking regulations set forth by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (Basel II) imposed much stricter capital requirements on banks designed to prevent a repeat of the financial crisis. Lower leverage will undoubtedly mean that these firms will be less profitable in rising markets. The flip side of that observation is that these firms will be more profitable and less prone to large losses in falling markets and thereby still be able to fulfill their public utility roles when most needed.

Regulation should be geared toward ensuring the stability of financial institutions, not maximizing their profitability. The fact that reducing their balance sheet leverage will reduce their profitability should be completely irrelevant in determining the best manner in which to maintain their capital adequacy. Moreover, if financial institutions were less profitable, they would likely be in a weaker position to lure America’s most talented students with lucrative compensation offers to become investment bankers and derivatives and mortgage traders. That would be nothing but a boon for U.S. society, which would greatly benefit if these talented individuals were instead to become scientists, engineers, doctors, and teachers.

Capital requirements also need to be maintained on a countercyclical rather than pro-cyclical basis. For too long, financial institutions were permitted or encouraged to reduce their capital when times were good, leaving them with insufficient capital cushions when economic conditions deteriorated. The old adage about saving money for a rainy day may be quaint, but it has survived for hundreds of years because it makes a great deal of sense. Regulators and stockholders frown upon banks and other financial institutions over-reserving for losses because this results in understating earnings, but a more sophisticated approach to reserves (and measuring bank profitability) is needed. Annual financial results are nothing more than an accounting convention, and many of the financial arrangements into which banks and other institutions enter are far longer in tenor than one year. Accordingly, it would be far more appropriate to tie reserves on longer-dated contracts to their tenor on a fully disclosed basis to permit investors to make a more informed evaluation of an institution’s reserve policy. Moreover, regulators are generally ill-equipped to set predetermined reserve requirements for complex financial instruments, and if anything should encourage institutions to err on the side of over-reserving rather than under-reserving in order to ensure that there will be adequate capital cushions when markets inevitably seize up again. A far more flexible regime is needed than a one-size-fits-all capital model. Finally, little attention should be paid to stock market investors on this issue. Reserves are intended to prevent exactly the type of irrational panics to which stock market investors are particularly prone, and they are the least qualified arbiters of capital adequacy in the marketplace.

FDIC insurance should also become subject to a countercyclical regime. In the past, prosperity has given rise to reductions in the amounts of insurance that banks were required to pay into the insurance fund. This proved to be a fateful mistake as the FDIC was rendered seriously insolvent in 2009 by a rash of bank failures. It would be far wiser for insurance rates to be maintained at high levels in strong markets, when banks can afford them, than to create a situation where these fees have to be drastically increased in the middle of a crisis to keep the fund from running out of money. Like many things, management of the FDIC is subject to the human proclivity to believe that current conditions will persist, particularly when such conditions are healthy. Regulators need to exercise imagination and consider that benign conditions are likely to encourage risk-taking and lead to trouble for which a bigger insurance fund will be needed.

Compensation Reform

Any attempt to rein in financial institutions’ balance sheet leverage after the crisis needed to include compensation reform. Asymmetric compensation schemes that favored short-term profitability over sustainable long-term financial health greatly exacerbated the balance sheet weaknesses that contributed to the financial crisis. Paying out hundreds of millions of dollars of cash compensation to their executives left firms such as Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers with diminished capital cushions to absorb losses on their mortgage and loan portfolios when the crisis occurred. Compensation reform was needed to stabilize the capital bases of systemically important institutions.

The good news is that the Obama administration (as well as European governments) took important steps to rein in—at least for the moment—the most egregious pay practices in the financial industry. On October 22, 2009, the Obama administration’s Special Master for of Compensation, Kenneth Feinberg, and the Federal Reserve, unveiled a two-front attack on Wall Street’s pay practices. Mr. Feinberg, working out of the Treasury Department, set limits on the compensation practices of companies that received financial aid from the government during the crisis and had not yet paid it back: Citigroup, Bank of America, AIG, GMAC, General Motors Corp., Chrysler Corp., and Chrysler Financial Corporation. While these limits reportedly still left several dozen employees at these firms earning in excess of $1 million of long-term compensation, they could fairly be described as draconian (at least in Wall Street terms).11 On the same day, the Federal Reserve announced that it would incorporate compensation reviews into its routine regulatory supervision of banks, which would affect all institutions regulated by the central bank, including those that received government support during the crisis and were able to pay it back. At the time, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke said the purpose of the new rules was to tie pay to long-term performance and to ensure that pay schemes do not create “undue risk for the firm or the financial system.”12 While these steps did not cure the plague of overcompensation in the financial services industry, they were a constructive attempt to remove the asymmetry from previous pay schemes that led executives to make one-way bets with what turned out to be other peoples’ (that is, the government’s or the American taxpayer’s) money.

The payment of huge amounts of cash compensation severely weakens the balance sheets of financial institutions. Accordingly, limits must be placed on the amount of cash compensation that is paid out every year by these firms. A much greater percentage of compensation should be paid in the form of stock that vests over an extended period of time. This will strengthen balance sheets in two ways—first by increasing the firms’ cash balances, and second by increasing the amount of equity on their balance sheets. It will also help to align the incentives of the biggest earners with those of the stockholders and other stakeholders who want the firm to survive by taking prudent risks. But even if it doesn’t align these interests, it will at least keep more cash where it belongs: inside the firm.

While the senior executives of failed firms owned enormous stock positions (worth hundreds of millions of dollars or more at their peak valuations), these large ownership stakes still failed to instill the necessary ownership mentality and fear of risk. This is likely because these executives were not only granted obscenely large stock option grants annually, but were also paid tens of millions of dollars of cash compensation and retirement benefits each year by the boards of directors and compensation committees that were stacked with their cronies. A study by three Harvard Law School professors showed that executives at Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers cashed out $1.0 billion and $1.4 billion, respectively, of performance-based compensation from cash bonuses that were not clawed back and from stock sales during the 2000–2008 period.13 Lehman Brothers’ former chairman and chief executive officer Richard Fuld reportedly cashed out more than $500 million of compensation while Bear Stearns’ former chairman and chief executive officer James Cayne made off with more than $350 million. Though these men lost hundreds of millions of dollars in stock value when their firms failed, they remained among the wealthiest Americans in the wake of the crisis and the collapse of their firms. This is the epitome of the heads-I-win, tails-I-win-anyway compensation schemes that most executives on Wall Street enjoyed in the years leading up to the 2008 crisis.

Moreover, simply as a matter of common sense and moral decency, Wall Street compensation became grossly disproportionate to any contributions any individual could possibly make to a public company or to society. It is one thing when the owner of a private company earns outsized compensation; that individual is assuming the entire risk of the enterprise. In a public company, all of the expenses of operating the business are paid by others and do not fall on individual executives. Public company executives are sheltered from business risks (for example, the costs of defending litigation) by the financial wealth of the corporation, and there should be some sort of limitation on the upside that accompanies that protection from the downside. Effectively, public company executives have a one-way ticket to earn cash compensation with no return ticket to put any of that cash at risk. This is the real objection to the sky-high bonuses that were paid on Wall Street—they reflected a completely one-sided compensation arrangement in which executives suffer limited pain if their firms experience failure. These types of arrangements must be terminated because they breed a loss of confidence in the fairness of the system, which in turn erodes the moral bonds that encourage the types of constructive conduct that allows markets to function. If the directors of these firms are not prepared to make the necessary changes to these schemes, then the government should step in. The government properly has a role to play in limiting such schemes if losses are going to be socialized when financial firms fail. Firms simply cannot be permitted to perpetuate such asymmetric compensation schemes in an era when the ultimate risk of payment falls on the U.S. taxpayer.

In view of the fact that large amounts of money will continue to be paid to financial executives (even with the Federal Reserve and Treasury Department breathing down their necks), the lion’s share of compensation should be paid in the form of stock whose ownership vests over an extended period of years. Stock compensation should be based on several years of performance and include provisions that adjust awards appropriately (known in Wall Street parlance as claw back provisions) in order to avoid the error of rewarding executives for short term performance that later turns out to be illusory. For example, a senior investment banker should not be rewarded with a blank check for working on a transaction that later turns out to fail; his or her ultimate compensation should be related to the success or failure of the deal. This would be an important step to leading investment bankers to work on deals that are likely to succeed and avoid working on deals that are likely to fail (such as a highly leveraged private equity transaction). Regulators should permit firms to maintain reserve accounts and make other arrangements to facilitate these types of compensation structures and require detailed disclosure to keep investors fully informed.

Moreover, such compensation arrangements would ideally focus executives on the overall financial health of their firms and lead them to be more prudent when taking risks. They would also be designed to inculcate a culture focused on shared responsibility and respect for risk-taking, two attributes that are far too rare in the financial services industry. This might also encourage firms to develop cultures in which professionals are required to speak up when they spot reckless behavior or wrongdoing, which would further enhance systemic health. These are ideals, of course; we all know that individuals go to Wall Street primarily to make large sums of money, not to rescue puppies. Nonetheless, it is long past the time when society stopped divorcing doing well from doing good. Generous compensation and respect for the system and the institutions that pay compensation should not be mutually exclusive. In fact, the sooner people realize that these values are mutually reinforcing, the healthier and wealthier the financial system will be.

Compensation is particularly important because the powerful interests in our society repeatedly decide to bail themselves out at the expense of the disenfranchised. After the financial crisis, Former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker pointed to this flaw in the system and urged bank speculation to be reined in. “I do not think it reasonable that public money—taxpayer money—be indirectly available to support risk-prone capital market activities simply because they are housed within a commercial banking organization. Extensive participation in the impersonal, transaction-oriented capital market does not seem to me an intrinsic part of commercial banking. . . . I want to question any presumption that the federal safety net, and financial support, will be extended beyond the traditional commercial banking community.”14 Volcker was suggesting—correctly—that it would be a profound policy error to continue to permit institutions to speculate in a system that socializes their losses. His influence led to the so-called Volcker Rule that now prevents federally insured institutions from speculating with their own capital.

Reforming Monetary Policy

It is time to acknowledge that the pro-cyclical policies of the Federal Reserve consistently place the United States’ economy on an unsustainable path and that a countercyclical policy approach must be adopted. The evidence for this is the pattern of booms and busts that dominated the financial markets over the past 30 years. This pattern proved to be highly disruptive to economic growth as well as damaging to the returns that investors earn on their capital. Furthermore, important trends in the financial markets exacerbated the pro-cyclical bent of monetary policy: the globalization of markets, the digitalization of finance, and the consolidation of the financial industry.15 With markets increasingly likely to lean in the same direction, it has become imperative that monetary authorities learn to lean in the opposite direction to temper imbalances. The age of allowing imbalances to build until they burst and then cleaning up the mess should have come to an end with the crisis of 2008, but most surely it did not.

Alan Greenspan will probably spend the rest of his life defending his tenure as chairman of the Federal Reserve. Once considered the elder statesman of The Committee to Save the World, his tenure was significantly discredited by the financial crisis that unfolded shortly after he departed the most powerful position in global finance. The “Greenspan put,” which morphed into the “Bernanke put” in the hands of his successor and then into the “Yellen put” in the hands of his successor Janet Yellen, created an environment of moral hazard that was repeatedly exploited by the private sector. By constantly resorting to what some economists have termed “preemptive easing” to prevent short-term pain,16 Greenspan may have won individual battles but managed to lose the war. His policies set the United States on an unsustainable path.

The pattern of policy making since the mid-1980s was clearly pro-cyclical and created an environment that encouraged moral hazard, beginning with the reaction to the stock market crash of 1987. In order to reassure the markets in the aftermath of their 508-point drop on October 19, 1987, Chairman Greenspan promised them that the Federal Reserve stood ready to make available whatever liquidity was necessary to assure their smooth operation. This was a highly appropriate response to an unprecedented one-day drop in the stock market averages. Unfortunately, however, it became the canned response to far less critical threats. Monetary easing in response to real or perceived crises spawned bubble after bubble.

Easing in the late 1980s led to a property bubble that resulted in the savings and loan crisis in the United States in the early 1990s. Low rates in the early 1990s that were invoked to deal with fallout from the savings and loan crisis and resulting recession spurred a decline in the U.S. dollar in the mid-1990s (and dollar-linked Asian currencies in Thailand and Indonesia) and contributed to the Asian bubble that burst in 1997. Low rates also played a large role in the Long Term Capital Management debacle of 1998 (allowing the hedge fund to borrow virtually infinite amounts of cheap money to leverage itself into oblivion) as well as the Russian default of that year, which led to further emergency easing that contributed to the absurd and unsustainable boom in technology stocks beginning in 1999 and ending in tears in 2001. Greenspan also didn’t miss a chance to react to the false alarm that all of the world’s computers would supposedly shut down at midnight on December 31, 1999 (we all might be better off if they had) by keeping rates lower than he should have in the middle of what was the most obvious stock market bubble in recent memory (the NASDAQ peaked at a price/earnings ratio of 351 times during that folly). When the Internet bubble burst and dragged down the corporate credit markets that were dominated by billion-dollar debt offerings for telecommunications and technology companies that in many cases didn’t even qualify as early stage venture capital start-ups, the Federal Reserve maintained low rates in order to protect the markets from themselves once again. This led to the credit bubble of the mid-2000s that fed mortgages and corporate credit with the able assistance of the shadow banking system of structured credit, SIVs, and derivatives. By the time that bubble burst, the systemic imbalances that were permitted to build up under the aegis of the Federal Reserve were so profound that it was little wonder that capital had to be given its last rites in the fall of 2008.

The Federal Reserve and its misguided chairman didn’t accomplish this alone. The nation’s inability to bear the least amount of economic pain contaminated every level of the financial and political system. Every time the “R” word (recession) was mentioned, the political classes went into a trance and began quoting Joseph Conrad’s Mr. Kurtz—“The horror! The horror!” The United States had fallen far from the days of the Greatest Generation. The American body politic has grown insufferably intolerant of the least degree of hardship. The possibility of a mere recession has become such an anathema to the political classes of this country that it leads policy makers to pull out all the short-term stops to prevent a downturn while completely ignoring the long-term consequences of such a strategy.

This inordinate fear of the slightest economic downturn ignores the fact that recessions are completely normal and absolutely necessary in a capitalist economy. More important, it neglects the basic economic truth that pain deferred is pain increased. Little or no attention was paid each time the potential of an economic slowdown was raised to whether the remedies would sow the seeds of deeper problems later. The Federal Reserve chairman found more-than-willing co-conspirators in the United States Congress, whose inability to rein in spending over the past three decades illustrates beyond a shadow of a doubt that today’s U.S. government bears little resemblance to the one envisioned by the Founders. No doubt there was corruption back when the country was formed, and there has been corruption ever since in various forms, but today’s corruption is so deeply embedded into the system that it threatens the very future of this country. Drastic measures are needed to reverse course.

The Federal Reserve is justifiably subject to intense criticism by certain members of the political class not only for its actual performance, which has fed one bubble after another, but also for its lack of transparency. Congressman Ron Paul has been in the forefront of this movement. Certainly there should be no reason why the central bank should not set an example for high standards of transparency. In fairness, under Chairman Ben Bernanke and his successor Janet Yellen, the central bank has taken major steps to become more open in its operations. But the bigger issue is one of substance, not form. The Federal Reserve must make an intellectual shift toward a countercyclical policy approach and away from the pro-cyclical policy regime that it has followed since the Greenspan years. Effectively, the Federal Reserve has functioned as a massive momentum machine, feeding liquidity into the market at points when it perceived that it was needed and letting it run too long. You can’t day trade a twenty trillion dollar economy, yet that is what the Federal Reserve is trying to do. This has left the U.S. economy with too much debt, too much capacity in too many industries and too few sources of internal growth. In September 2009, capacity utilization in the U.S. and European factory sectors (they are linked in today’s global economy) had fallen to a depressed 65 percent and facing a slow recovery. Other sectors of the U.S. economy, such as retailing, hospitality, commercial real estate, and financial services (the latter after shrinking significantly in 2008 and 2009), were also suffering from significant overcapacity. It has taken years for capacity utilization to recover and it is still below optimal levels in 2015. The repercussions of pro-cyclical policy will reverberate through the economy for years to come.

Private sector actors are going to do whatever they can to maximize their profits. After all, as discussed in the previous chapter, it is their fiduciary duty to do so, even if their actions hurt the overall economy. If low-cost leverage is available and can increase profits, economic actors will use it. Accordingly, the maintenance of artificially low interest rates is an invitation for people to borrow and spend.17 Part of the goal of monetary policy at various times in recent years was clearly to encourage risk-taking and the use of leverage. Until the financial crisis forced Chairman Bernanke and his colleagues to become far more aggressive and creative in employing the tools of the central bank (some might argue in contravention of the law), the primary tool used to manage monetary policy was the Federal Reserve’s ability to set the overnight lending rate between banks, known as the Federal Funds rate or the discount rate. The problem is that the overall policy bent has been highly asymmetric—the Federal Reserve has been much quicker to lower rates and ease liquidity at the least sign of economic stress than to raise rates and tighten the flow of money when conditions improved.18

But during the Greenspan years, and the first couple of years of Bernanke’s term that preceded the crisis, the Federal Reserve also refused to aggressively address growing imbalances in the economy. One reason for this hands-off approach was the oft-stated rationale that monetary policy should only be tightened to battle inflationary threats. This approach was based both on a narrow interpretation of the central bank’s mandate and on Alan Greenspan’s belief that it is impossible to identify a bubble when it is occurring. While one would have hoped the latter view would have been discredited by the Fed’s failures, it is clear by the Fed’s refusal to take any action to raise rates until December 2015 that it has not.

Contrary to Greenspan’s oft-repeated assertion that it is impossible to identify a bubble, there are clear indicia of when asset prices are rising to unsustainable levels. Moreover, it doesn’t require a bubble to justify the imposition of countercyclical policies. Any significant departure from long-term valuation trends should capture the attention and concern of central bankers and trigger a response. But the types of deviations from the norm that occurred in the decade preceding the crisis of 2008 were far more than mere departures from long-term trends; they were obvious bubbles that required no special economic knowledge to identify. Stock prices traded at a multiple of 351 earnings on the NASDAQ Stock Exchange at their peak on March 10, 2000; the average price/earnings multiple at previous market peaks was no higher than 20.19 The risk premium (known as spread) on Credit Suisse’s High Yield Index reached 271 basis points over Treasuries on May 31, 2007, a record level that exceeded the historical average of 570 to 580 basis points by over 50 percent.20 Asking central bankers to rein in liquidity when markets reach such extreme points of overvaluation is a far cry from asking them to overstep their mandate. Central bankers have the tools at their disposal to counteract such trends, and they should use them more proactively than the Federal Reserve has done. There is a better answer than simply choosing between stepping aside and letting bubbles run their course and creating a command economy with too much government intervention and control.

It was apparent to many observers, including this author,21 that technology and Internet stocks were experiencing a bubble at the turn of the millennium. The Nasdaq Composite Index was trading at a valuation of more than 20 times higher than its previous peak. The housing market was experiencing a similar unsustainable rise in prices in the mid-2000s when housing prices were well outpacing the growth in personal income. The corporate debt market was trading at unsustainable levels on the eve of the financial crisis when spreads were more than 50 percent tighter than historical norms. The fact that the Federal Reserve either did not recognize these bubbles or simply ignored them is either a severe indictment of its monetary management or a clear sign that formal reform of its mandate is overdue. Today’s economy and markets would be unrecognizable to the people responsible for founding the Federal Reserve in 1913, and the central bank’s original mandate needs to be revisited. The world cannot afford more pro-cyclical policies that ignore bubbles that are blowing up in central bankers’ faces and inflicting damage for which future generations will be left to pay.

Respected authorities such as the Bank for International Settlements have begun to call for countercyclical monetary policy management in recent years. Such a policy is often confused—deliberately perhaps by opponents—as a form of targeting asset prices, but such criticism is misplaced. Asset prices are a symptom of an underlying disease, not the disease itself. Monetary policy is designed to treat diseases, not symptoms, and should be more proactive in addressing burgeoning imbalances in order to help avoid the immense damage that market crises impose on economies and societies. No system can be perfect and eliminate imbalances, but a better system than the one operating today would proactively tighten policy by raising interest rates and tightening liquidity conditions based on movements in certain economic indicators.

Economist William White suggests the following indicators as some of those that might give rise to proactive tightening: “unusually rapid credit and monetary growth rates, unusually low interest rates, unusually high asset prices, unusual spending patterns (say very low household saving or unusually high investment levels).” He also suggests that “unusually high external trade positions” be considered.22 I would add a series of more specific indicators, including corporate credit spreads, mortgage spreads, differentials between changes in house prices and changes in personal income levels, and the absolute level of existing interest rates. The key question monetary authorities should be asking is whether markets are underpricing risk. The proper pricing of risk (which is an art and not a science) is one of the most effective ways to prevent systemic imbalances from growing out of control and creating threats that turn into crises. Consideration of these factors in the fashioning of monetary policy would be a major improvement over the current narrow focus on inflation, which is itself a far different phenomenon than it was in 1913 when the Federal Reserve’s original mandate was implemented.

Enhancing Systemic Transparency

One of the keys to encouraging productive investment and discouraging speculation would be to improve systemic transparency. Obscurity is the enemy of stability. If investors are deprived of the information necessary to evaluate specific securities or markets, they are incapable of accurately determining the level of risk they are assuming or that financial institutions are assuming. If they are not provided with the information regarding the holdings of financial institutions because these holdings are being concealed in off-balance-sheet entities, investors can’t possibly evaluate the financial condition of these institutions. Without the ability to make that determination, investors are deprived of the ability to accurately evaluate financial industry or systemic risk. This increases uncertainty, which in turn leads investors to lose trust more easily in their counterparties and the markets themselves. Increasing uncertainty and decreasing trust in market mechanisms leads to less rational behavior as investors act to protect their own interests regardless of the consequences for the system, leading to full-blown market sell-offs like those we saw in 2008. Opponents of transparency need to understand that they are not only harming the system but they are hurting their own interests by ultimately promoting systemic instability.

If there is one common denominator among speculative practices in the financial markets, it is that they tend to be opaque. Earlier chapters in this book examined two of these practices in detail: private equity (and related strategies that invest in nonpublic market securities) and derivatives. Each of these strategies depends in part on the ability to obscure investment holdings (and their valuations) from the prying eyes of investors and regulators. This is done in a number of different ways. For private equity and other nonpublic market strategies, obscurity is obtained through investments in securities that are not traded on a public market and can only be valued through highly subjective procedures that are unverifiable with any degree of certainty by reference to independent pricing sources. For derivatives (and related quantitative strategies), prices are obscured by how the instruments or trades themselves are dressed up in mathematical complexity that most investors and regulators are incapable of understanding.

As a result of these stratagems, these investment programs are effectively operating in regulatory and due diligence vacuums with few checks and balances. At best, it is up to auditors to confirm the validity and the accuracy of prices and investment returns, and auditors only offer post hoc reviews of investments and trades and can do little to prevent fraud or other abuses while they are occurring. Moreover, auditors generally have limited knowledge of the substance of what they are reviewing, so any protection they afford is extremely limited. Accordingly, the link between non-productive investment strategies and opacity is deeply embedded and intentional. That link must be identified, and then these strategies must be forced into the light.

Ban Structured Investment Vehicles

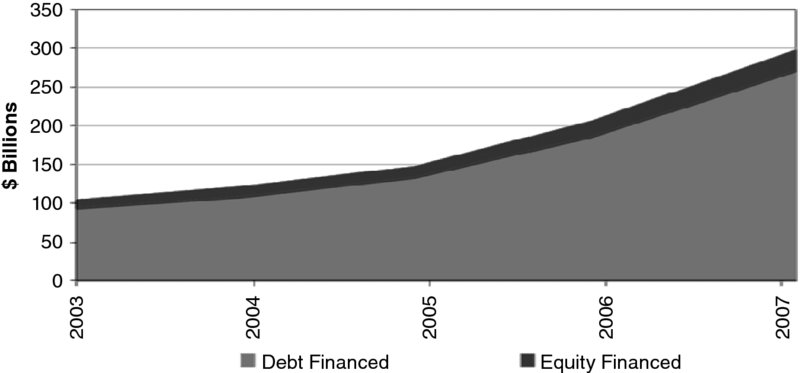

There were times during the 2008 crisis when it felt as though the authorities were not going to be able to stop the stampede of panic selling that was threatening to send the markets into a tailspin from which they would never recover. Perhaps the greatest fear motivating panic sellers was fear of the unknown, which was hardly surprising in view of the revelations about hundreds of billions of dollars of highly risky assets that the world’s largest financial institutions were concealing in undisclosed SIVs. The assets held in these vehicles were not included in traditional measures of these firms’ leverage, which left regulators and investors in the dark with respect to the risks that these institutions were facing. As these entities lost their access to short-term funding in late 2007, legal commitments as well as reputational concerns and governmental and regulatory pressures forced tens of billions of dollars of these assets back onto the balance sheets of their sponsoring institutions, further burdening already overleveraged balance sheets and in some cases threatening outright insolvency. These SIVs were a large part of the shadow banking system that was able to operate outside the purview of regulators and permitted financial institutions to employ even more leverage than the already high levels of leverage they used on their balance sheets. Figure 9.1 shows the growth of these vehicles in the years prior to when the walls came crashing down.

Figure 9.1 Growth of SIVs' Total Assets

SOURCE: Standard & Poor's.