CHAPTER 1

The 2008 Crisis— Tragedy or Farce?

In 1852, Karl Marx wrote that history tends to repeat itself—the first time as tragedy, the second as farce.1 Nowhere has this warning about man’s compulsion to repeat his mistakes been more frustrating to witness than in the world of finance. When it comes to finance, there is only one certainty: Mistakes will be repeated again and again until their perpetrators lose their minds, their jobs, their money, or all of the above. The worst part is that professional perpetrators will lose all of their clients’ money as well as their own. If the working definition of insanity is repeating the same mistake over and over again while getting the same bad result, then Wall Street is a living exemplar of an insane asylum. Not only do Wall Street, policymakers, and regulators repeat their mistakes, they always manage to commit larger, more expensive and more reckless ones each time around.

While driving to work at the Beverly Hills offices of the investment bank Drexel Burnham Lambert, Inc. early one morning in February 1990, I wasn’t thinking about Marx’s dictum. But by the time I drove home that afternoon (earlier than planned), I was living it. The last thing I expected that day was to be called into a meeting and told that one of the most powerful firms on Wall Street was going to declare bankruptcy later that day. I was blown away. At the time, Drexel had all of $3.5 billion in assets and was the biggest underwriter of junk bonds in the world. At the time, it all seemed like a very big deal.

Less than 20 years later, what happened at Drexel seems like small potatoes. In September 2008, Lehman Brothers Holdings, Inc., became the first large investment bank to fail since Drexel, except it was 200 times larger than my former employer with a $600 billion balance sheet. Lehman conducted business with virtually every significant financial entity in the world and its collapse threatened the stability of the global economy.

But Lehman Brothers was only the tip of the iceberg. The Bush administration and the Federal Reserve were simultaneously facing an even bigger threat that required their immediate attention: the potential collapse of insurance giant American International Group (AIG). Just a couple of days later, the government was forced to step up and bail out AIG with $85 billion of capital to avoid what would have likely been an extinction-level-event for the global financial system had AIG been allowed to go under. AIG sported a $1 trillion balance sheet and had seen fit to sell trillions of dollars of credit insurance on subprime mortgages without properly understanding or pricing their risk.

The Death of Capital

In the immediate wake of Lehman’s bankruptcy and AIG’s near-demise, capital died. Economic activity came to a grinding halt around the world. Financial markets collapsed. Lenders stopped lending. Counterparties refused to honor their obligations. The global financial system faced its most severe crisis since the Great Depression as the flow of capital ceased. Figures of economic authority in both the public and private sectors lost all credibility. Reassuring words offered by Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke and Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson rang hollow. President Bush seemed to be hiding in the White House bunker. And other important financial firms were literally facing extinction.

Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, once considered among the strongest financial institutions in the world, were pushed to the brink of failure by speculators in the thinly traded credit default swap market who were able to raise the firms’ borrowing costs with trades involving relatively small amounts of capital. Merrill Lynch, once known as the “Thundering Herd,” was revealed to be the “Dundering Herd” under the incompetent leadership of Stanley O’Neal and had to be sold overnight to Bank of America in a hasty transaction that raised myriad legal and ethical questions whose niceties were brushed aside during the heat of the crisis. The U.S. government was forced to play whack-a-mole as it veered from one crisis to another and ended up engaging in a prolonged and unprecedented series of direct and indirect interventions into the economy that ended up costing trillions of dollars and continue to have enormous and largely negative repercussions to this day.

The world learned a very hard lesson: financial markets are built on nothing more than a thin tissue of confidence and the belief that promises and commitments will be kept. Tragedy or farce, call it what you will, this crisis was the real deal. People were angry. They shook their heads and asked, “How could things have come to this?” They should have been asking instead, “How could we have reasonably expected things to turn out otherwise?”

Those of us who warned that markets were heading for a fall had been dismissed as Cassandras, just as we were treated when we issued similar warnings during the Internet Bubble that led to a spectacular crash in stocks and the credit markets in 2000–2001. When this book was originally published in 2010, the immediate crisis appeared to be over and a veneer of stability had returned to the financial markets. But the underlying economies on which markets must ultimately depend remained structurally weak, and the path toward sustained economic growth was still out of reach. Two years after the crisis, policymakers were still wrestling with how to restore financial stability. And seven years later, they have still not succeeded; the global financial system remains highly fragile. In order to forge a sustainable future, we need a better understanding of the sources of instability that caused the last financial crisis and are leading us straight into another one.

The reasons why we are heading toward another crisis are obvious and irrefutable. Since 2009, fiscal and monetary policy have failed to address the underlying problems that led to the 2008 financial crisis: too much debt and too little economic growth. The post-crisis market and economic recoveries were almost exclusively the result of an unprecedented explosion of debt around the world. By the end of 2014, global debt had grown to roughly $200 trillion, an amount that can never be repaid. Posing additional systemic risk is roughly $650 trillion of derivatives sitting on the balance sheets of the world’s largest financial institutions. While debt grew by more than 40 percent in the six years after the financial crisis, the economy only expanded by 18 percent during that period. The disparity between economic growth and debt growth demonstrates that the world is losing the ability to generate the income necessary to service its growing debt burden. Something is going to have to give.

There are only four ways to repay debt: currency devaluation; inflation; default; or growth. Since the rate of growth required to generate the income necessary to service the current stock of debt is higher than can reasonably be expected, that option is no longer feasible. That leaves the other three options, all of which are versions of the same outcome—repayment of debt at less than its face amount in constant dollars. This leaves policymakers and investors facing difficult choices in the years ahead. And the longer the day of reckoning is delayed, the more difficult those choices are going to be.

Seeds of Instability

The Committee to Destroy the World explores three key characteristics of modern economies and markets that contributed to their instability and ultimately caused the crisis that permanently wounded world capitalism in 2008 and have, if anything, accelerated since then.2 These characteristics are the following:

- Finance Dominates Industry. The financial markets have overtaken the industrial and manufacturing sectors as the dominant force in the global economy. The financial sector has grown much faster than other sectors of the economy over the last few decades. Since 1970, the financial sector’s share of national income in the U.S. and U.K. has more than doubled.3 Finance, which I define as applied economics, dominates not only the economy but culture, politics, science, and virtually all human endeavors. Finance dominates industry and manufacturing as the motive force of modern Western economies.4 Some historians, such as the eminent French historian Fernand Braudel, argue that the dominance of finance is a sign of a civilization’s waning power. Whether that will prove to be the case for the United States and Europe remains to be seen.

- Markets Are Governed by Flawed Intellectual Assumptions. Despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary, the financial system is structured on the assumptions that markets are efficient and investors are rational. Both assumptions are patently false. Furthermore, the laws that govern investor behavior require them to focus on narrow short-term economic considerations at the expense of long-term economic and social factors that would contribute to a more equitable and, in the long run, wealthier global economy. Many current investment strategies are based on concepts such as diversification and correlation that need to be revised in light of technological changes that have altered market structures. The work of great economic thinkers such as Adam Smith, Karl Marx, John Maynard Keynes, and Hyman Minsky should be reread to revise our understanding of capital to reflect the fact that capital is a highly unstable process (as opposed to a static object) that must be managed and regulated far more effectively than it has been in the past.

- Speculation Trumps Productive Investment. As a result of the rise of finance and misguided regulation of the financial services industry, a disproportionate amount of financial and intellectual capital is devoted to speculation rather than to productive investment. As the size and importance of the financial sector increased during the three decades leading to the financial crisis, the deregulated financial industry created incentives for capital to be directed to unproductive activities such as housing and leveraged buyouts of twilight industries that needed to be retooled rather than weighed down with new debt. By the mid-2000s, massive amounts of capital were used to leverage up the balance sheets of dying businesses such as newspapers and automobile manufacturers in what could only generously be termed a lost cause and might truly be deemed a farce (in Marx’s sense of the word). Had that capital been devoted to more productive uses, far fewer jobs might have been lost and fewer factories might sit idle today.

Since the financial crisis, a tidal wave of regulations has been unleashed to try to redress these problems. While these regulations left the U.S. financial sector nominally better capitalized than before the crisis, they did not address the hundreds of trillions of dollars of derivatives that still sit on these institutions’ balance sheets and pose a systemic risk that few people truly understand and virtually nobody wants to discuss honestly. These regulations also left the U.S. financial system more concentrated, more rigid, and less liquid. This leaves markets more vulnerable to financial accidents and more prone to crisis.

A Word on Speculation

Speculation is one of the most important concepts discussed in this book. Speculation describes economic activities that do not add to the capital stock or increase the productive capacity of the economy. Instead, financial speculation involves economic activity that is not intended to create lasting economic value but is merely intended to generate short-term financial profits. Whether or not such activities are intended to be productive is another question, but by and large economic actors do not pay attention to such questions in their quest for immediate gratification. The growth of finance has contributed to a deeply unfortunate trend in Western societies in which an incalculable amount of intellectual and financial capital is devoted to activities that do not contribute to the productive capacity of the global economy or to the improvement of the human condition.

Speculation is hardly new to the U.S. economy. As Lawrence E. Mitchell describes in his book, The Speculation Economy, speculation is hard-wired into the legal structure of American business. Professor Mitchell dates this phenomenon back to the end of the nineteenth century.

It was only during the last few years of the nineteenth century that business distress combined with surplus capital searching for investment opportunities, changes in state corporation laws, and the creative greed of private bankers, trust promoters and the newly evolving investment banks created the perfect storm that shifted the production goals of American industry from goods and services to manufacturing and selling stock.5

The type of speculation that Professor Mitchell describes is endemic to the very capital structure of the American corporation. “Waves of watered stock created by the giant modern corporation brought average Americans into the market for the first time. The instability of these new securities and the corporations that issued them provided enormous opportunity, both intended and not, for ordinary people and professionals alike to speculate, leading sometimes to mere bull runs and sometimes to widespread panic.”6 The instability inherent in corporate capital structures is a microcosm of the systemic instability described by Hyman Minsky in his “financial-instability hypothesis,” a subject discussed in Chapter 3 of this book. The important point to understand is that speculation leaves room for capital to make mischief. Rather than finding a home in productive uses, speculative capital nests in areas where it sits and festers, creating imbalances that later come home to roost.

The great economic historian Charles Kindleberger defined “pure speculation” as “buying for resale rather than use in the case of commodities, or for resale rather than income in the case of financial assets.”7 This is a polite description of what is colloquially known as the “Greater Fool Theory,” which gained an increasingly prominent role in financial markets during the series of expanding bubbles that characterized the U.S. economy and financial markets over the past 30 years. Buying on the basis that someone else will come along and pay more for your assets became a national pastime in the U.S. housing market in mid-2000s, and returned in full force to both public and private equity and debt markets during the post-crisis, central bank-fueled bull market that began in 2009.

Since the financial crisis, speculation assumed a new form as the global economy began to cannibalize itself. In the public sector, the Federal Reserve’s unconventional “quantitative easing” policy led it to purchase trillions of dollars of debt issued by the United States Treasury and other agencies of the U.S. government. Between 2009 and October 2014, the Federal Reserve purchased more than $4 trillion of Treasuries and agency securities that are currently sitting on its roughly $4.5 trillion balance sheet. This policy was copied by Mario Draghi’s European Central Bank, which launched its own $1.1 trillion bond purchase program in early 2015, just a few months after Haruhiko Kuroda’s Bank of Japan announced an even more radical program in October 2014 that included the purchase not only of Japanese Government Bonds but stocks and ETFs.

These programs are designed to lower interest rates on the theory that low interest rates will stimulate economic activity. But while they undoubtedly lowered interest rates and inflated stock and bond markets around the world, they utterly failed to create sustainable economic growth. Instead, consumers and businesses reacted to lower interest rates in ways that central bankers did not expect. Consumers opted to save rather than spend, while businesses devoted their capital to stock buybacks rather than expansion and hiring. The best laid plans of central planners fell completely flat once again.

This is most apparent in Corporate America. Since the financial crisis in 2009, U.S. corporations repurchased more than $2 trillion of their own stock. In many cases, they borrowed large amounts of money to do so, weakening their balance sheets in the process. These repurchases accelerated as stock prices rose, completely belying the argument that corporations are savvy buyers of their own stock who only buy when their stock is cheap. In fact, they generally do the opposite and buy more stock as the price rises. For the most part, they are responding to the incessant demands of institutional shareholders as well as executive compensation schemes that reward managers for boosting stock prices in the short-term regardless of the negative long-term consequences.

Economies that eat their own are doomed to perish. I am unaware of any race of cannibals that has thrived in the history of mankind. Eventually cannibals run out of victims. Rather than cannibalistic economic policies, the world hungers for pro-growth policies. These policies exist; what is lacking is the political and moral courage to carry them forward.

Financialization

In addition to the destabilizing characteristics of modern markets and economies described above, a series of changes within the actual business of finance were key contributors to systemic instability whose only logical outcome was the 2008 financial crisis and future crises. All of these changes come under the common heading of financialization, which in its broadest sense speaks to the increasingly dominant role that finance assumed in Western economies in the decades leading to the financial crisis. These features, many of which were addressed by new post-crisis regulations, included the following:

- The transition of financial institutions, in particular banks, from deposit-taking and lending institutions into risk-taking institutions.

- The increasing utilization of debt instead of equity as a source of capital at all levels of the private and public sector.

- The growth of an unregulated “shadow banking system” that consists of a nexus of private equity funds, hedge funds, money market funds, nonbanks such as GE Capital, and special purpose entities such as collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) and structured investment vehicles (SIVs) that moved control of the money supply beyond the reach of central banks.

- Dramatic changes in the short-term money markets that included the utilization of riskier assets in products that were marketed as low risk such as money market funds.

- The explosion of credit derivatives, structured credit products and other derivative financial instruments that supplanted cash securities.

- Enormous growth in the private equity business.

- Increased reliance on mathematical models to govern investment decisions.8

These pre-crisis changes were all manifestations of three trends: an overall shift in economic activity away from production in favor of speculation; toward opacity and away from transparency; and toward debt and away from equity. The result was an emphasis on business and investment practices that increased the tolerance for risk and dramatically increased the instability of the financial system.

Post-crisis, many of these destabilizing trends were addressed. Money market funds were reformed to reduce the risks they took in the period leading up to the crisis. Large banks are no longer permitted to risk their own capital to the extent they did before the crisis thanks to the Volcker Rule. U.S. banks are much better capitalized and much less leveraged than in the period prior to the crisis (the same cannot be said of European banks, which remain dangerously leveraged). SIVs were largely outlawed. More disturbingly, little has been done to address the potential threat posed by derivatives. While many consider the largest institutions “too big to fail,” it would be more appropriate to consider them “too big to save” since the volume of derivatives they hold is unthinkably large and nobody can genuinely claim to know what will happen. The only statement that can be made with certainty is that in the event of a crisis, a significant number of the counterparties to these derivatives contracts will not be in a position to meet their obligations, triggering a daisy-chain of defaults that would threaten the solvency of the highly leveraged global financial system.

The singular failure of post-crisis policy is the inability of the global system to grow via equity rather than debt. As a result, the system is more fragile than ever. In The Committee to Destroy the World, financialization is understood as the process whereby the credit system makes increasing amounts of capital available for speculative rather than productive economic activity. Financialization is supported by lax regulation and a blind belief that markets will always make optimal capital allocation decisions. In 2008, the American economy led the global economy into what one astute observer described as “a crisis of financialization . . . a crisis of that venturesome new world of leverage, deregulation, and financial innovation.”9 Despite the heavy hand of regulation that came down on the financial system after the crisis, financialization remains a potent force in the economy and broader society.

The financialization of the U.S. economy was facilitated by two broad trends. First, as noted, regulatory and other business policies favored financial speculation over production. This took the form of accounting and tax laws that favored debt over equity and also permitted companies to disguise their true financial condition. As a formal matter, this favoring of speculation led to a system governed by formal rules that fictionalized the depiction of economic reality. These rules included:

- Accounting conventions that bear little relationship to reality (for example, the treatment of stock options and the allowance of non-GAAP earnings adjustments that grossly inflate corporate earnings).

- Accounting and tax rules that privilege debt over equity.10

- Tax rules that favor a small class of entrepreneurial capitalists so disproportionately that it created an American oligarchy to rival the Russian one that grew up in the shadow of the fall of the Soviet Union (including but not limited to the “carried interest” tax break that favored the earnings of the private equity and hedge fund industries).

- A proliferation of complex financial products that purported to reduce risk but actually increased it on a systemic basis (the first instance being portfolio insurance that contributed to the 1987 stock market crash and the latest manifestation being credit insurance in the form of credit default swaps that pushed several large financial institutions into insolvency).

The denouement of the deregulatory orgy came in two parts: the 1999 repeal of The Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 that originally prevented commercial banks from entering businesses thought to be unduly risky; and the Securities and Exchange Commission’s disastrous 2004 relaxation of net capital rules limiting the amount of leverage that the major investment banks could assume on their balance sheets.

Citigroup, Inc. was one of the main promoters of Glass-Steagall repeal under its former Chairman Sandy Weill; within a decade it was a ward of the state. The megabank spent the decade following Glass-Steagall repeal (under the chairmanship of former Treasury Secretary and proponent of Glass-Steagall repeal Robert Rubin, who joined the bank a wealthy and respected figure and departed a decade later much wealthier but far less respected) failing to combine its various businesses; breaking securities and banking laws in the United States, Japan, and elsewhere; forming multibillion dollar off-balance-sheet entities to conceal liabilities from the prying eyes of regulators, credit rating agencies, and investors; playing a key role in championing the Internet bubble through the offices of, among others, the disgraced telecommunications analyst Jack Grubman; and losing tens of billions of dollars in ill-advised mortgage and corporate loans before being forced to come hat in hand to the U.S. government for multiple bailouts. It took less than four years for three of the firms that joined Citigroup in lobbying to be allowed to break the leverage barrier in 2004—Bear Stearns & Co., Inc., Lehman Brothers Holdings, Inc., and Merrill Lynch & Co., Inc.—to blow themselves up with their newfound powers. These rule changes were based on intellectually flawed rationalizations that were given establishment imprimaturs by Nobel Prize winners and a radical free-market ideology that gained a blind following after the collapse of a Soviet system that failed based on its own deficiencies, not as a result of the genius of the American economic system.

The second facilitator of financialization was the U.S. legal system. One could fill the Library of Congress with books describing the flaws of the U.S. legal system. For the purposes of understanding the death of capital in 2008, however, there is one particular area of American jurisprudence that has been particularly damaging: the law governing fiduciary duty. Over the past century, the U.S. legal system developed a body of law governing the conduct of fiduciaries that privileges the short-term economic interests of a company’s shareholders over the long-term, noneconomic interests of society. This resulted from the adoption of what is referred to as the “agency approach” to the corporate governance challenge of aligning the interests of shareholders and management in public corporations. The agency approach promoted the view that the best way to align the interests of corporate managers and shareholders is to align their financial interests, and established that the primary or sole purpose of corporations is to maximize shareholder returns within the confines of the law.11 As a result of this ideology—and it is nothing other than an ideology, because it is simply a human thought-construct—corporate managers and boards of directors are legally required to place the interests of shareholders ahead of those of creditors, labor, the environment, and other parts of society that are arguably equally deserving of consideration.12

One of the most pernicious consequences of the imposition of a narrow profit maximization motive on corporate boards of directors was the flood of private equity transactions that consumed the public equity markets in the United States beginning in the 1980s and continuing through the eve of the financial crisis. The concept of maximizing value for shareholders was used by corporate raiders, leveraged buyout artists, and other private parties to wrest control of numerous public corporations from the hands of public shareholders. In the early days of the private equity industry in the 1970s and 1980s, this arguably pressured public company managements to improve efficiency and productivity and contributed to better management and business practices. Unfortunately, by the mid-1990s and continuing through the beginning of the 2008 financial crisis, this morphed into little more than substituting debt for equity on corporate balance sheets and diverting untold billions of dollars into private hands at the expense of public shareholders. Moreover, the going-private phenomenon imposed an enormous opportunity cost on the U.S. economy in terms of lost jobs, reduced research and development (R&D), and meaningfully lower productive investment in America’s future. But it was sanctioned by the view that shareholders of public corporations were entitled to obtain the highest possible value for their stock (and the belief that the market for corporate control is the most effective way of delivering that result).

Since the financial crisis, a new manifestation of this phenomenon arose: the rise of “activist investors,” who are just a more respectable version of the corporate raiders and “greenmailers” of the 1980s. These “activists,” who with rare exceptions (such as Nelson Peltz) never ran an operating business themselves, force companies to raise their dividends and buy back large amounts of stock (often with borrowed money) in order to meet their obligation to “maximize shareholder value.” Even the venerable Warren Buffett joined forces in 2014 with the Brazilian private equity firm 3G to purchase large companies like Heinz and Kraft and is now resorting to “rationalizing” operations through thousands of job cuts in order to “maximize” shareholder value. This is just another version of cannibal capitalism, and growth through subtraction is unlikely to provide the kind of expansion of employment, R&D and capital spending that will add to GDP in the years ahead. It is dangerous to believe that rising stock prices (which can drop as easily as rise) are an economic panacea especially when they are driven higher by cheap debt and cost cutting rather than higher productivity and sustainable revenue growth. All too often the forces that drive up stock prices exact a terrible toll on other parts of the economy that are not properly factored into the thinking of the institutions whose short-term interests are allegedly being served when activists drive up the value of their stockholdings.

The narrow reading of fiduciary duty that was adopted by U.S. courts may seem to be consistent with the interests of traditional laissez-faire capitalism, but is, in fact, directly contrary to the teachings of Adam Smith and other theorists of capital, as the following pages explain. Moreover, the development of the law of fiduciaries has had a questionable effect on corporate creativity and social conduct. It provides legal justification for short-sighted investment and business strategies that diminish the productive capacity of the economy while encouraging speculative activity that harms businesses and communities. The non-shareholder interests that are deliberately pushed to the side by fiduciaries—the rights of workers, the health of the environment, the long-term contributions made by corporations to their communities in supporting social and educational programs—are at least as important in building a robust economy as maximizing value for shareholders in the short term. There is not and never has been anything preordained in this interpretation of the law. Instead, this interpretation of the duties of corporate managers was a dubious intellectual and moral choice that must be challenged in order to develop a more just society and a healthier and more productive economy.

The Corruption of Moral Sentiments

There is another crucially important reason why we need to question traditional economic and legal thinking to understand how markets continue to get things so terribly wrong intellectually, strategically, and morally. In 2008, as in earlier crises, the markets were victims of a lowering of ethical standards and a thorough corruption of moral sentiments. This was hardly the first time such lapses occurred; this behavior followed a familiar pattern in which conduct that in earlier periods was clearly considered illegal, immoral, or simply feckless somehow became accepted as conventional behavior that was widely practiced, acknowledged and tolerated.

In the Internet bubble, one example of this type of conduct was the participation of research analysts in marketing initial public offerings of newly minted Internet companies that had few prospects for success. Securities laws were supposed to prevent such behavior, yet even the largest and ostensibly most reputable investment banks deployed their analysts in this manner. After the Internet bubble burst, high-tech companies engaged in a new set of shenanigans when they began repricing or resetting the dates on stock options for their top executives. Leading up to the 2008 crisis, questionable but widely known behavior was less a matter of breaking the law than violating common sense: the use of egregious amounts of leverage by virtually every participant in the financial markets (individuals, non-financial corporations, investment banks, hedge funds, private equity firms, commercial banks) in every financial activity imaginable from home ownership to the most arcane trading strategies.

These dangerous borrowing levels were in no way illegal; in fact, they were expressly sanctioned by the government. We already noted the changes in net capital rules that were implemented in 2004 by the Securities and Exchange Commission that allowed five large investment banks to increase their borrowings, ultimately pushing the leverage ratios of some of the firms that subsequently failed from 12-to-1 to over 30-to-1 (meaning that a mere 3 percent drop in asset values could render them insolvent—and in at least three cases that we know about, it did). This leverage was used to increase the short-term profitability of these firms with little regard to the long-term risks involved because their executives were compensated based on asymmetric schemes whereby they profited greatly if their firms made money but also remained obscenely wealthy even if their firms failed. As a result, firms like Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers were left in the hands of modern-day Captain Ahabs like Richard Fuld and James Cayne who could afford to watch their ships sink while retaining enormous personal wealth. Everybody knew how leveraged these firms were in 2006 and 2007 but virtually nobody spoke up to warn of the possible dangers to the financial system posed by their creaky capital structures. Markets are based on incentives. In the years leading up to the 2008 crisis, the incentive structures of Western financial markets became totally corrupted. The types of excesses seen in the last two bubbles dwarfed those of the Gilded Age or the Reagan Years. America did not suffer simply an economic crisis; it also suffered a moral crisis.

Since the financial crisis, however, we learned that the largest institutions engaged in and continue to engage in illegal and unethical conduct on what can only be considered a systemic scale. While it should surprise nobody to learn that there was widespread wrongdoing associated with the mortgage business that fed the Housing Bubble that was a proximate cause of the financial crisis, pervasive lawbreaking among the financial elite also extended to manipulation of the London Interbank Offered Rate (Libor), the lifeblood lending rate of the financial markets, the foreign exchange markets, the credit default swap market, the Treasury market, and the most extensive insider trading scandal in Wall Street history. These violations spanned the period prior to, during and after the financial crisis and included not only serial but repeat offenses by virtually every major financial institution in the world. The violations demonstrate that there is something seriously rotten at the heart of modern finance. While institutions pled guilty to criminal charges, virtually no senior executives were held to account for these crimes. One might be tempted to believe that these acts were committed in a vacuum, but unfortunately they were perpetrated by highly educated executives who knew better. The fact that individuals went unpunished breeds deep cynicism for the law and disrespect for the institution of finance.

Low Rates and Lax Rules

It was within the context described above that the economic forces that were building for years pushed the global financial system to the brink of insolvency in 2008. In an operative sense, the two proximate causes of the crisis were years of loose monetary policy and recklessly lax financial regulation, both of which were driven by free market ideologies that grew ascendant during the Reagan/Thatcher years.

Beginning in 1981, global interest rates began a long-term secular decline that continued through the financial crisis of 2008 (and the post-crisis period). These low rates pushed up asset values and financed higher debt-financed consumption funded by countries running current account surpluses whose exchange rates were tied to the dollar. Moreover, debt and consumption growth came to exceed income growth, a situation that was unsustainable. At some point, people have to pay for what they consume, and have to be able to repay their debts. Or so it would seem. As the United States recovers from the measures that were required to avoid a complete collapse of the global banking system in 2008, it is facing years of sustained high structural unemployment, below-trend economic growth, and huge deficits as far as the eye can see.

The financial world that almost collapsed in 2008 was far different from the world that was shocked by the U.S. stock market crash just two decades earlier in 1987. Financial markets were light years more technologically advanced this time around. Portfolio insurance, which contributed to the 1987 stock market crash, was primitive in comparison to the derivative weapons of mass destruction that brought the markets to their knees two decades later. Unfortunately, neither regulation nor traditional investment practices sufficiently adapted to this new regime. The explosive growth of the financial sector in Western economies created a single, interconnected global market for money and credit that no longer operated according to the old rules. Instead of being governed by sovereigns, the world came to be ruled by currencies and interest rates that were no longer confined by national boundaries. Two closely linked manifestations of the emergence of finance as a dominant force led to tears. First, the invention of credit derivatives, so-called insurance products, facilitated speculation on an unprecedented scale. Second, the banking system became supplanted by its shadow, a parallel universe of financial institutions that operated outside the control of regulators while concealing their true financial condition from investors, regulators, and lenders.13

Free market ideologies justified and reinforced the ascendancy of finance, but failed to adequately account for the radical changes that technology and globalization wrought in the fabric of the markets. Supply-side economics, which called for lower taxes and less government involvement in the economy, failed to account for the pro-cyclical nature of human behavior and the necessity to rein in the basic human instincts of greed and fear. Financial thinking on the part of investors as well as regulators failed to reflect the underlying changes in the markets and the economies whose goods they trade.

Western capitalism transformed over the past 30 years into one dominated like no time in history by financial markets where financial instruments are traded rather than manufacturing markets where goods are produced. In this phase of capitalism, every economic object is reduced to some type of marketable or tradable financial instrument. The accumulation of wealth is no longer based on the production of hard or tangible assets; today’s wealth is dominated by intangible forms that financial technology renders interchangeable and readily tradable on the world’s financial markets. The result is a global economic system that is constantly shifting below our feet. Most of the time, those shifts are incremental and manageable. But at other times, change speeds up, or changes that have been occurring over time suddenly accelerate and present a new set of economic conditions to which we have to adapt quickly. At these moments, the markets move in ways that change the course of history. Black Monday 1987 was one of those days. In 2008, we saw several such days when the stock market moved in 1,000-point arcs and credit markets froze up as though nobody would ever make another trade or extend another loan. While changes in markets themselves affect the course of history, they importantly reflect changes occurring in the world outside the markets, the most important being those wrought by the minds of men.

By the time the crisis of 2008 materialized, finance, and the rules ostensibly designed to protect finance from itself, were woefully unprepared to manage a system that had changed profoundly from the world in which the rules were written. In a world of feedback loops that operate with exponential rather than linear force, and where discontinuities are woven into the fabric of market reality, traditional investment and regulatory theories were rendered anachronistic. One explanation for what was happening is that a digital world was playing according to analog rules. Another explanation is that a globalized world was operating according to local rules. The crisis revealed that time-honored modes of thinking about concepts such as risk needed to be retrofitted to new realities. Most important, investors needed to start coming to terms with the fact that markets are not efficient and investors are not rational. How could investors be presumed rational when their thinking failed to reflect the radical changes that were occurring in markets and societies around the world?

The Global Liquidity Bubble

Abundant global liquidity gave investors a plethora of opportunities to invest based on these flawed beliefs over the last three decades. Investors who understand how to read the business cycle, which is heavily influenced by global liquidity flows, flourished in recent decades. Beginning in the mid-1980s, the world became awash in capital as a result of a series of historic economic shifts that created enormous trade and capital imbalances throughout the global economy. These shifts were accompanied by advances in financial technology that facilitated the creation of new forms of money to soak up this global liquidity. After capital became untethered from gold in the early 1970s, there was literally no limit to how much capital could be created. As a result, too much capital killed capital.

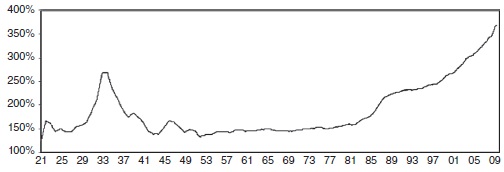

Two broad economic phenomena in the years leading up to the financial crisis illustrate the financial debacle that ensued in 2008. First, the growth of debt consistently exceeded the growth of underlying Western economies. Figure 1.1 illustrates the inexorable growth in debt in the United States over the past several decades. In the United States, total debt as a percentage of GDP grew from 255.3 percent in 1997 to 352.6 percent in 2007.14 It should also be noted that, for the first time, debt levels beginning in the early part of the 2010s began to constitute as great a percentage of GDP as they did during the Great Depression.15

Figure 1.1 United States Total Debt as Percent of GDP

SOURCE: Bridgewater Associates, Inc.

This accumulation of debt was facilitated by the ability of financiers to literally create liquidity out of the air through financial innovations such as collateralized debt obligations (which packaged up trillions of dollars of individual mortgages, automobile loans, corporate bonds or bank loans, and other types of debt) and credit default swaps (a form of insurance on debt instruments such as bonds and mortgages). As new forms of capital were spawned, debt began to grow at an extremely rapid and ultimately unsustainable pace.

As significant as the growth of debt was prior to the financial crisis, the explosion of debt after the crisis was simply breathtaking. It is both mindboggling and inexcusable that business and government leaders are not more outspoken about the dangers posed by the suffocating burden debt is placing on the global economy; they are clearly too invested in the current system to challenge a status quo that threatens to deliver another crisis to our door in the near future. Their silence is a profound betrayal of their obligations as public servants and citizens.

Second, in the years leading to the financial crisis, an increasingly globalized financial system married excess savings in developing countries with a dearth of savings in developed countries. This devil’s bargain of borrowing and lending created dependencies that ultimately grew into pacts of mutual financial destruction that, in terms of their threat to global stability, came to replace the Cold War nuclear weapons pacts of a generation earlier.16 As a result, emerging market economies accumulated trillions of dollars of dollar-denominated debts with insufficient resources to repay them.

Neither of these phenomena—massive global liquidity and money flows between developed and developing countries—could be maintained without the business of finance, whose transformation further increased instability. A world in which physicists made it possible for competing powers to blow the physical world to smithereens by splitting the atom was rendered financially unstable by financial engineers deconstructing financial instruments into 1s and 0s and then recombining them into highly leveraged lethal weapons. With far more capital than could reasonably be put to productive use, the world’s largest investors began to direct these explosives into highly speculative activities that were disguised in one of two ways. Some of these speculative activities were hidden in plain sight, like the equity and credit markets where asset prices exceeded all reason and new standards of valuation were cooked up by so-called experts to try to justify “new, new things.”17 Other activities were hidden in the “shadow banking system,” a complex web of nonbanking institutions whose holdings and true financial condition were deliberately concealed by the largest financial institutions in the world from the eyes of regulators and investors.

The immediate result was the near collapse of the global economic system and the world’s financial markets in 2008. The long-term result is prolonged and entrenched government involvement in previously lightly regulated capitalist economies and years of sluggish post-crisis economic growth that is likely to persist even if economies can be weaned off government support (something that appears to be increasingly unlikely with every passing quarter of disappointing post-crisis growth). Trillions of dollars of capital were directed to speculative activities such as derivatives trading, leveraged buyouts, and other investments that added little or nothing to the productive capacity of the economy in the pre-crisis years. In the post-crisis years, trillions of dollars were directed to various types of cannibalistic activities such as stock buybacks and quantitative easing that failed to ignite organic economic growth, leaving economies more indebted and less vibrant than before. These funds were wasted, and they are lost forever. Even in a perfect world, much of this new capital would have undoubtedly found its way into unproductive uses. But a more proactive fiscal policy regime could have directed capital to areas that are both productive and life-enhancing such as education, medical and scientific research, infrastructure improvement, and projects to improve the environment. It may not be too late, but it is getting awfully late in the game. Economies urgently need to start implementing pro-growth policies that can start directing capital to areas where they can stimulate growth.

The less-than-optimal allocation of capital was the logical result of a series of miserable policy choices. Monetary policy was strongly pro-cyclical rather than countercyclical and tended to favor debt over equity and speculation over production. Other regulatory policies that governed the financial markets during this period—capital standards, accounting rules, tax laws—led the financial sector to conduct business in a manner that exacerbated rather than limited risk. Economic actors respond to incentives and that is what they did. Rather than leading financial institutions to ease credit during boom periods and tighten credit during downturns, policy led institutions to do just the opposite. This had the unintended and destabilizing effect of intensifying cyclical changes in the economy. Rather than leading individuals and institutions to save for a rainy day and create a cushion to permit them to survive economic downturns, these policies led them to spend when they should have saved and borrow when they should have repaid debt. The result was that capital was scarce when most needed and abundant when least needed and least able to be put to productive uses.

Too much money chasing too few goods is supposed to be inflationary, but the normal processes that cause inflation were moderated over the past three decades by technological changes and the entry of billions of low-cost workers from the developing world into the global economy. These changes suppressed labor costs and gravitated against rising inflation during most of this period. But these disinflationary forces are receding while financial assets experienced an unsustainable inflationary boom since the crisis. By the same token, too much money chasing too few productive opportunities is bound to lead to speculation. Bad money supplants good money; debt supplants equity. This is the classic crisis of capitalism that Karl Marx predicted, except that instead of products seeking out new markets, finance capital itself became the product looking for new outlets. Unfortunately it found all too many willing buyers of whatever new products Wall Street could cook up.

The credit crisis was the logical result of the proliferation of debt (and the substitution of debt for equity in virtually every kind of capital structure imaginable) that was eating away at the stability of the United States’ most important financial, legal, and social institutions for decades. The U.S. banking system finally collapsed in 2008 under the weight of trillions of dollars of bad loans that never should have been made in the first place. These loans were the deliberate result of decisions made by individuals who personally profited from them at a societal cost that will be calculated for decades to come. It may look like the mess was cleaned up, but it only looks that way. In addition to the trillions of dollars that were flushed down the drain, the opportunity costs are incalculable. The collapse of America’s financial markets in 2008 was an outward sign of the potential beginning of the end of U.S. global hegemony. The crisis in financial markets demands that policy makers engage in a radical rethinking of the mantras of free market ideology that have misled U.S. economic and legal policy for the past several decades.

A Crisis of Confidence

In human terms, what triggered the credit crisis and resulting collapse in financial markets was a loss of confidence on the part of virtually every institution and investor of significance. The financial system is based on trust. Financial actors of all sorts—both individuals and institutions—lost trust in each other by the end of the summer in 2008. As a result, they stopped doing business with each other on the most basic level. Banks stopped making loans, and stock and bond traders refused to trade with each other. It took historic and unprecedented government actions to restore this trust. The kind of trust that allows markets to function builds up over many years, yet it is very fragile and can evaporate overnight. Once lost, it is very difficult to regain. The fact that markets began to recover in March 2009 should not be taken as a sign that the past can be forgotten.

The question that should be on the minds of all investors going forward is what could trigger another crisis. The answer is that it will be the same thing that caused the last crisis—a loss of confidence in the system and central bankers. Central bank policies that stopped the global financial system from collapsing failed to create the conditions for long-term prosperity and caused many negative unintended consequences. Rather than stimulate spending, low interest rates led economic actors to increase savings. Rather than leading to higher growth, monetary policy led to slower growth. Rising stock prices fed by easy money distracted investors from these disturbing truths, but sooner or later reality will smack them over the head. When it does, there will be another crisis of confidence and markets will fall—and they will fall hard.

The crisis created other sinister long-term consequences. The flawed financial products and investment strategies that were responsible for what happened originated in the hearts of Western capitalism—the towers of Wall Street and the City of London. The crisis of confidence that resulted from the failure of borrowers to meet their obligations can be laid directly at the feet of the largest financial institutions and gatekeepers in the world, and all of these are Western-based. As a result, confidence in the Western model of capitalism suffered a body blow. The credit rating agencies and investment and commercial banks that promulgated the subprime mortgage debacle were profoundly discredited intellectually and morally by their conduct.

The fact that this occurred during a period when U.S. foreign policy isolated the world’s dominant economic power from its traditional allies and rightly or wrongly made it the target of hatred among large sectors of the world population may be a historical accident or may be suggestive of broader historical trends. The Obama administration’s profoundly misguided attempts to apologize for American power only made matters worse when the world learned that America could no longer be counted on as a reliable ally or global leader. The United States exited the first decade of the twenty-first century far weaker than it entered it. And rather than blaming others, the financially and militarily most powerful country in the world needs to look within and figure out how to do better.

We are still tallying the total damage from the credit crisis, but the final cost will be tens of trillions of dollars. But this capital wasn’t lost—it was murdered. As much as we should blame failures of human character and emotion (greed and fear), we must also blame failures of human intellect (stupidity). The most highly educated segment of our population—the PhDs, the MBAs, the JDs—made inexcusable errors of judgment, raising legitimate questions about the utility of such degrees when they fail to include a modicum of common sense and, more important, common decency in their curricula. As the holder of more than one of these degrees, I am highly aware of their shortcomings.

There is a huge difference between being educated and being smart. The credentialed individuals that continually lead the world into one crisis after another—which includes The Committee to Destroy the World—are of two types. The first lacks the type of real world experience that teaches humility and allows them to make smart decisions. The second are political animals who serve their own interests rather than those of the people who appointed or elected them. Either way, their pedigrees conceal hollow cores that are revealed by the catastrophic consequences of their work. Until the world learns to value honest dissent and outside-the-box thinking over the moral cowardice of groupthink and consensus, we will continue to be guided by people who may be educated but who aren’t remotely smart.

This is why nothing seemed amiss to most people while the world was going mad in the years leading up to the crisis. We had Ben Bernanke assuring everyone that plunging housing prices in the mid-2000s would not cause a crisis. And institutions like the International Monetary Fund demonstrated its ignorance of financial markets by pompously (and cluelessly) claiming that “growing recognition that the dispersal of credit risk by banks to a broader and more diverse group of investors…has helped make the banking and overall financial system more resilient.”18 In fact, some of us who were actually trading in those markets were warning that risk was not being widely dispersed but was in fact being more concentrated among a limited number of investors. But those of us who issued such warnings were sharply criticized and often ostracized. Errors of intellect and judgment were endorsed by some of the most respected business and government leaders in the world. Alan Greenspan in particular repeatedly made public comments endorsing policies that in retrospect turned out to be extremely reckless. At the time, however, these policies were part of an economic orthodoxy that few were willing to question. From an economic standpoint, this orthodoxy overlooked the important role that asset prices play in the economy as well as the increasing role that debt was playing in the growth of the economy. It also failed to account for concepts such as discontinuity, path dependency, and feedback loops that can wreak havoc on an economy and markets. The failure to include these considerations in economic analysis led to fatal deficiencies in policy.

Lionized by some, Greenspan’s reign as Federal Reserve chairman should be judged by history as an abject failure of policy and intellect. Greenspan himself felt compelled to admit that his worldview was flawed when, early in 2009, he told Congress that he had relied on his belief that financial actors would act in their own best interest while failing to understand that individual self-interest is often contrary to the public interest. In an exchange with Representative Henry Waxman, Greenspan admitted that “those of us who have looked to the self-interest of lending institutions to protect shareholders’ equity—myself especially—are in a state of shocked disbelief.” Waxman responded by saying, “In other words, you found that your view of the world, your ideology, was not right, it was not working.” The former chairman responded, “Absolutely, precisely [perhaps the clearest answer Greenspan had ever given to Congress]. You know, that’s precisely the reason I was shocked, because I have been going for 40 years or more with considerable evidence that it was working exceptionally well.”19 Had he been a student of Hyman Minsky instead of Ayn Rand, Greenspan would not have made such a fatal error.

In 1986, Minsky warned that, “the self-interest of bankers, leveraged investors, and investment producers can lead the economy to inflationary expansions and unemployment-creating contractions. Supply and demand analysis—in which market processes lead to an equilibrium—does not explain the behavior of a capitalist economy, for capitalist financial processes mean that the economy has endogenous destabilizing forces. Financial fragility, which is a prerequisite for financial instability, is, fundamentally, a result of internal market processes.”20 By ignoring the internal processes that led to an unsustainable buildup of low-cost debt, central bank policy under Greenspan fueled a false prosperity. Coupled with tax and other economic policies that were aimed at rewarding speculative rather than productive investment, the result was a gutting of the United States’ economic base and a mortgaging of its future.

Unfortunately, Mr. Greenspan’s successors learned little from his mistakes. While Ben Bernanke was rightfully praised for taking actions that prevented a complete collapse of the financial system during the financial crisis, he perpetuated these policies long after they were justified. His pre-crisis policies and failure to see the Housing Crisis unfold are also serious marks against him. His successor Janet Yellen and the rest of the Federal Reserve Governors kept interest rates at zero for far too long and engaged in a series of quantitative easing moves that failed to create sustainable economic growth. Yet rather than change course, they kept doubling down on these failed policies, leaving the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet swollen with debt, financial markets starved of liquidity and reliable price signals, the economy rife with massive misallocations of capital, and the global economy awash in trillions of dollars of debt that can never be repaid.

The best face that can be put on this policy approach is that the Federal Reserve views the global economy as stuck in a simmering crisis from which it will miraculously emerge if policy is left loose enough for long enough to allow growth to re-ignite. But that is a false hope. A more realistic assessment is that the Federal Reserve is run by a group of former tenured economics professors who never managed a business or sat on a trading desk and have little understanding of how the real world works. Rather than prompt people to spend, low interest rates led people to save money. Rather than promote sustainable economic growth, QE loaded the world with trillions of dollars of debt that is suffocating growth. The world is heading toward another financial crisis when markets figure out that these policies will never produce their intended results.

Why Finance Matters

Students of history understand that the consequences of these errors are not merely theoretical. When I am asked by young people what course of study they should follow if they want to pursue a career in finance, I tell them to study History, Psychology (preferably mass psychology), Philosophy, and Economics in that order. History is the best education for people interested in learning about markets because it teaches how the world reacts to change—and change is the only constant in markets. As Winston Churchill famously said: “The further backward you look, the further forward you can see.”

In The War of the Worlds, a history of the blood-soaked twentieth century, historian Niall Ferguson argues very persuasively that economic volatility coincides with social instability. He defines economic volatility as “the frequency and amplitude of changes in the rate of economic growth, prices, interest rates, and employment, with all the associated social stresses and strains.”21 Professor Ferguson makes a strong case that “ethnic conflict is correlated with economic volatility. A rapid growth in output and incomes can be just as destabilizing as a rapid contraction. A useful measure of economic conditions, too seldom referred to by historians, is volatility, by which is meant the standard deviation of the change in a given indicator over a particular period of time.”22 He explains (in words that sounded eerie written on the eve of the 2008 financial crisis and echo even more disturbingly after witnessing the chaos wrought in America’s inner cities and around the world by years of failed Obama administration foreign and domestic policies) that:

Economic volatility matters because it tends to exacerbate social conflict. It seems intuitively obvious that periods of economic crisis create incentives for politically dominant groups to pass the burdens of adjustment on to others. With the growth of state intervention in economic life, the opportunities for such discriminatory redistribution clearly proliferated. What could be easier in a time of general hardship than to exclude a particular group from the system of public benefits? What is perhaps less obvious is that social dislocation may also follow periods of rapid growth, since the benefits of growth are very seldom evenly distributed. Indeed, it may be precisely the minority of winners in an upswing who are targeted for retribution in a subsequent downswing.23

Even the least historically minded among us need not be reminded that World War II and the Holocaust followed the Great Depression. In 2016, the geopolitical situation is more unstable than any time since the end of the Cold War largely due to the deliberate decision of the Obama administration to abdicate America’s leadership role in the world.

The world is certainly far more dangerous than during the financial crisis. Russia’s incursion into Ukraine threatens Eastern Europe, NATO, and the post-World War II balance of power on the European Continent. China is asserting its hegemony in the South China Sea in a provocative manner. As a result of America’s retreat from Iraq without a Status of Forces Agreement, the Middle East is now experiencing a Sunni-Shia war and the rise of radical Islam, including the rise of ISIS and the revival of Al Qaeda. Syria is a charnel house as Bashar al-Assad commits genocide on his own people, triggering the largest refugee crisis since the Second World War. He is actively supported by Russia and Iran in the wake of Barack Obama’s decision to enter a strategically and morally indefensible deal with Iran that will provide the world’s largest state supporter of terrorism a clear path to nuclear weapons by 2030. Terrorists are attacking Western cities like Paris with impunity while Mr. Obama and his former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton worry more about offending the vast majority of Muslims who are not terrorists than calling out those Muslims who are running around murdering people. This is the fractured state of the world in the age of Obama.

Back at home, the southern border of the United States is a sieve while the Obama administration refuses to enforce America’s immigration laws and allows sanctuary cities to harbor illegal immigrants who break the law. America’s inner cities are home to intolerable levels of poverty and out-of-control gun violence after five decades of failed progressive policies that are long overdue for reassessment. But honest dialogue about the causes of this violence are suppressed by political correctness that refuses to admit that it is primarily driven by blacks killing other blacks due to pathologies deeply embedded in their own communities. Black youth unemployment was over 30 percent in 2015 while 72 percent of black children and 53 percent of Hispanic children were born to unmarried women and 40 percent of all children were born to unmarried women in America in 2015 while a majority of all mothers under 30 are not living with the fathers of their children. The Obama administration lowered eligibility requirements for welfare payments and Social Security disability payments while pushing his failing healthcare plan on the American people. The results are rising levels of dependency that will result in rising budget deficits over the rest of the decade as the true trillion-dollar costs of ObamaCare start materializing. The fabric of American society is crumbling as economic change accelerates and we allow ourselves to be governed by policies that didn’t work in the past and aren’t going to work in the future.

As bad as things were at the end of George W. Bush’s presidency in 2008, they are considerably worse after nearly two terms at the hands of Barack Obama. The global economy is as fragile as in 1999 or 2007—years that preceded market meltdowns and recessions; the geopolitical landscape resembles 1910 or 1939, years that preceded major global wars; and America’s inner cities recall the Days of Rage of the 1960s. Our business and political leaders are fiddling while America is burning down. Without a radical course change, America and the world are headed for serious trouble.

The past has much to teach us about the consequences of ill-advised economic and foreign policies, but we needn’t search very far to see the damage that has been wrought. Our mistakes have exacted an incalculable human cost on the citizens in this country and abroad. Millions of people lost their homes and their jobs as a result of the subprime mortgage debacle. Toward the end of 2009, the official jobless rate in the United States was more than 10 percent and the number, when underemployed and discouraged workers were included, was over 17 percent. The real unemployment figure was probably in the vicinity of 20 percent. Economic hardship and the stresses unemployment causes led families to break up and addiction and suicide rates to rise. At the end of 2009, one in eight Americans was receiving at least some of his or her nutrition from food stamps, including one in four children. Communities around the country were destroyed by house foreclosures. Plant closures by the automobile industry devastated the American heartland. The social fabric of an already fraying society was badly damaged.

Six years after the crisis, things looked better but they were not as good as they looked. The unemployment rate in June 2015 had dropped to 5.3 percent, down from a peak of 10.8 percent in 2009 at the worst point of the post-crisis recession. U6, which includes discouraged and underemployed workers, was down to 10.5 percent from 17.1 percent at the same point in 2009. But if we look deeper, the job market is still in very bad shape. There are more people out of the workforce than at any time since the late 1970s. The labor participation rate was only 62.6 percent in June 2015, the lowest level since the 1970s, meaning that almost 100 million able-bodied Americans were unable to find full-time employment. If the job participation rate in June 2015 was the same as it was when Barack Obama took office in January 2009, the unemployment rate would be closer to 2009 levels. The Federal Reserve refuses to acknowledge that the low labor participation rate is an indication that there is a structural rather than a cyclical unemployment problem that is not susceptible to monetary remedies. Instead, in the absence of meaningful fiscal policy initiatives, the Fed keeps its foot on the gas of low interest rates and keeps praying for the best. Prayers work best in church and synagogue; their efficacy in the economy remains unproven.

Global Threats Require Systemic Stability

The world desperately needs a healthy financial system as it faces unprecedented strains on its resources, rising geopolitical tensions, and challenges to human survivability in the twenty-first century and beyond. Finance should not be treated like just another national pastime that is followed through the media like baseball or cricket. And the financial markets are not the economy, even though they play one on television. The markets are the lifeblood of human civilization. They are the organizations that enable us to feed and clothe and heal our fellow humans, and abusing them is no different than abusing ourselves and risking our future. Like the capital they shepherd, markets must be nurtured and protected, not abused and neglected and left to the offices of greed and fear.

Any serious book about markets today must be written with a consciousness of the significant challenges facing the human species as it enters the twenty-first century. There are many fine books on finance, but today’s world calls for something more. Finance needs to be understood as the force driving most of the social, political, ecological, and spiritual trends at work in the world. Unfortunately, many of these trends pose long-term threats to our species. Fixing the global financial system is not only an economic imperative—it is arguably a requirement for the survival of mankind. One telling example will suffice to illustrate what is at stake.

The world is facing a growing trend toward aging populations. Some countries like Russia and Japan are facing demographic disasters in the years ahead as their populations are projected to plunge in size. The costs of dealing with this inexorable demographic phenomenon dwarf the trillions of dollars that were spent by governments to prevent a global depression in 2008. Table 1.1, developed by the International Monetary Fund,24 shows how much each country spent on the financial crisis as a percentage of its GDP, compared to how much each country is projected to spend as a percentage of its GDP to deal with the cost of its aging population. The latter so far exceeds the former as to render the amounts spent on the financial crisis almost trivial in present value terms.

Table 1.1 Net Present Value Impact on Fiscal Deficit of Crisis Compared to Age-Related Spending as a Percent of GDP

| Country | Crisis | Aging | Age-Related Spending/Crisis Spending |

| Australia | 26% | 482% | 18.5x |

| Canada | 14 | 726 | 51.9 |

| France | 21 | 276 | 13.1 |

| Germany | 14 | 280 | 20.0 |

| Italy | 28 | 169 | 6.0 |

| Japan | 28 | 158 | 5.6 |

| Korea | 14 | 683 | 48.8 |

| Mexico | 6 | 261 | 43.5 |

| Spain | 35 | 652 | 18.6 |

| Turkey | 12 | 204 | 17.0 |

| United Kingdom | 29 | 335 | 11.6 |

| United States | 34 | 495 | 14.6 |

| Advanced G-20 Countries | 28 | 409 | 14.6 |

The column on the far right side of Table 1.1 divides projected age-related spending by crisis spending to show how future age-related spending is going to swamp crisis-related spending. For example, in the United States, age-related spending will amount to 14.6 times the amount that was spent on the financial crisis! Coincidentally, in all of the G20 countries, average age-related spending will also amount to approximately 14.6 times the cost of the financial crisis.

What Table 1.1 shows is that the United States and other G20 countries were facing forbidding financial challenges even before they had to step in with trillions of dollars of emergency funds in 2008. In other words, if we think we are facing fiscal challenges now, just wait until we get a few years down the road.

Moreover, beyond the example of aging populations and the cost of managing the financial crisis, there are other long-term threats to human survival, some of which require serious and immediate attention where a healthy global financial system will have to play an essential role.25

These threats, which are listed in Table 1.2, are by their very nature unpredictable and have the potential to trigger extreme impacts—in short, they are examples of the Black Swans that Nassim Nicholas Taleb brought into popular consciousness that have been circling in the skies above us throughout history. They are among the threats that mankind must confront and overcome in order to preserve its future.

Table 1.2 Future Black Swans?

Environmental degradation and climate change Nuclear proliferation Terrorism Population imbalances An increasing gulf between rich and poor Ethnic conflict A pandemic such as AIDS, SARS, or something worse World hunger |

If one adds the costs of addressing these issues (which are enormous but incalculable) to those found in Table 1.1, the potential magnitude is overwhelming. A negative outcome with respect to any of these potential crises would be a game-changer, resulting in exponential rather than linear damage: environmental catastrophe, a world war, a global health crisis, or a collapse of civil authority. These are precisely the type of discontinuities that the vast majority of investment strategies are unable to hedge against.

The world is going to have to search high and wide for the resources to deal with these threats. But even if it can find the resources, it will not be able to deliver them if the global financial system remains an unstable house of cards. A strong and stable financial system will be the bare minimum required to deal with these threats, and we don’t have such a system today. Moreover, such a system will have to be managed by men and women who possess not only raw intelligence and intellectual creativity but wisdom, real-world experience, and moral courage. Our finance-driven world, unfortunately, rewards only the first two of these attributes, and its failure to value the last three is nothing short of catastrophic.

People like Brooksley Born, the former chairperson of the Commodities Futures Trading Commission, whose advocacy for regulating the growing market for financial derivatives fell on deaf ears in the 1990s, are only recognized for their courage in speaking truth to power after the damage they sought to prevent is done. We need more Brooksley Borns and fewer Alan Greenspans, Lawrence Summers, and Robert Rubins, the men who rejected her recommendation to regulate derivatives based on rigid ideology rather than an understanding of the facts. The most highly celebrated individuals in public life repeatedly fail us, yet they are celebrated by a complicit and superficial financial and political media. Individuals in positions where they can make a difference in the world need to be smarter, wiser, and more courageous than their predecessors, very few of whom were willing to speak out or exercise their influence to upset the status quo. Just as polities get the leaders they deserve, societies get the financial systems they deserve. We must look inward to examine the deeply embedded cultural values and intellectual assumptions that consistently lead economic actors of all types—investors, regulators, corporate executives—to conduct themselves in a manner that places the stability of the financial system, and therefore of society, at risk.

The global economy and financial markets have yet to face the disruptive challenge of unwinding the massive amounts of stimulus that the world’s governments injected after the crisis in order to prevent a global depression. Seven years after the financial crisis, it remains very difficult to foresee how stimulus can be withdrawn without triggering serious market volatility. While many pundits were claiming throughout the 2013–2015 period that that the global economy was on the cusp of a self-sustaining recovery, there was in fact no evidentiary basis for making such a claim. “Self-sustaining” presumably means “without the support of central banks,” and markets have not experienced a single minute of existence without massive central bank support since the financial crisis. Accordingly, there has never been a basis for making any claim for a self-sustaining recovery since the crisis.

If economic growth is insufficient to fund not just ongoing deficits but the repayment of the trillions of dollars of debt already incurred, withdrawal of stimulus can only lead to slower or negative growth. One alternative is that stimulus simply won’t be withdrawn in any meaningful way, creating a situation in which massive government deficits will continue to grow as far as the eye can see. The U.S. federal deficit will soon pass $20 trillion and the annual cost of servicing that deficit will likely hit $1 trillion in the first half of the next decade; thus far, this cost has been mercifully suppressed by the low interest rates engineered by the Federal Reserve. But while mercy may have its limits, markets do not.

The only reason the financial system has not yet collapsed under its own weight is because interest rates have been maintained at zero since the financial crisis, but sooner or later investors will insist on a positive return on their capital. And when that happens, all hell will break lose. If the dollar was not the global reserve currency, an objective observer would view the U.S. balance sheet as resembling that of a country heading for a sovereign debt default. Other countries that defaulted on their debt did not have the privilege of issuing debt in the global reserve currency, but eventually the United States will no longer enjoy that advantage unless it radically changes its ways.