Chapter 7

Photographing People

When I interview new students I always ask them what they like to shoot and why they want to be photographers. Invariably one of them says, “I like shooting people.”

This is a big subject! What kinds of photographs of people do you like? Candids? Portraits? Why do you like making photographs of people? Is it because you get to engage and talk to them? Do you photograph the people you know, or is it all about observing strangers?

Pinpointing your reasons and interests is the first, and most crucial step, to making better photographs of the people in your life.

Portraits

My guess is that 90 percent of the photographs that the average amateur shoots are some form of portraiture. Most of the time, our subjects are people who are central to our lives. These photographs are some of the most important photographs you will ever take. They are the records of everyone who touched and helped define your life. You also touch and help define theirs. Looking at your photographs of friends and family can and should be a moving experience.

They might seem like simple snapshots, but they are so much more. If my hard drive crashed tomorrow, I could deal with losing the archive of my professional work (which is all backed up), but losing the photos of my family (which I’m sloppy about) would be devastating. These are the photos that bring me joy, and I take them as seriously as any assignment or fine-art project. (I gotta get a new hard drive!)

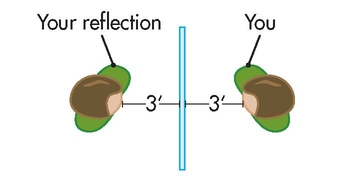

The Bathroom Mirror as a Camera

The way we see ourselves is directly influenced by what we see everyday in the bathroom mirror. We often look different in photographs, so a quick look at how the simple bathroom mirror works might be instructive.

Take a typical mirror about 18x24 inches in size. When we frame ourselves in the mirror, we are standing about two to four feet away. However, the optics of how a mirror works means that we are actually twice that distance from our image in the mirror because the light has to go from our face to the mirror and back again.

You can demonstrate this easily by focusing a camera on your reflection in a mirror and looking at the scale on the focusing ring. It will be twice the actual distance to the glass. If you focus on the surface of the mirror, your reflection will be out of focus.

Why We Look Different in Photos

When we hear someone say, “I hate the way I look in pictures!”, the important part of that statement is that he or she doesn’t hate the way he or she looks—only the way that he or she looks when photographed.

This is largely because in order to achieve the same head-and-shoulder cropping that we see in the bathroom mirror, we have to move the camera in close, typically about three to four feet away (or half the distance we see in the bathroom mirror).

Supermodels don’t look good that close up. Noses become too large, and ears disappear. It’s positively cruel to photograph someone with a short/normal lens. It’s also invasive. When I’ve been shot for television shows, I’m usually fairly at ease in front of the camera until it gets to about four feet away. Then, I become very self-conscious; I can’t stop looking at the camera sideways in candid shots, and I can’t look straight at it for an interview. It’s awful, and I would wager that most people feel the same way.

The Psychology of Portraiture

The brain behind the portraiture is another huge topic, but I think there are a couple of universal concepts that help make sense of it.

First, it starts with you. When I became a professional, I purposely started in a field (architectural photography) that never required me to shoot people. The simple reason was that I was painfully shy, and when you shoot photographs of people … guess what? They are looking back at you.

It’s the same fear of public speaking that many people have, that the audience is judging them. I had flop sweat every time I had to shoot a person. I couldn’t bear it. From talking to my students, I became aware that this is a very common experience. At least half of them find it difficult to photograph people for their own psychological reasons.

At a certain point, I realized that my inability to photograph people was a professional liability. I consulted with a sports psychologist for a year in order to get past a psychological handicap that was limiting my career. Now, I photograph people on almost every assignment, and I like it. I’m still nervous, but I can cope.

Second, it’s also them. Most people hate being photographed for the same reasons I hated shooting. It is painful to be looked at critically. Every time the camera clicks, they are aware that a judgment has been made—and they are right.

When you press the button, you have made a series of judgments and decisions. The shutter click is an audible signal to the subject that you saw something that you judged. It might have been good, but many of us are not very secure with our self-images.

This is why fashion photographers chatter and reassure models through an entire shoot. It tells the models (who are only human and often as insecure as anyone else) that they look good and that the photographer is interested in helping them look good.

How to See Others the Way They See Themselves

People are usually happiest with photos that conform to their self-image. So it’s not a bad idea to ask people flat out what they hate when they see themselves in photographs. Common complaints are:

• Crooked or large noses (easily mitigated by lens selection, posing, and/or lighting)

• Weak jaw lines and/or weight (lighting and posing makes a big difference)

• Receding hairlines (lighting and camera angle can help a lot)

The most important thing about asking them the question is psychological. The question tells them that you care about making them look as good as you can.

Here again, I use the bathroom mirror as the model. I ask my subjects to check their appearance in the mirror to see whether they are happy with their hair and makeup, and I watch them as they do this. When you watch subjects looking in the mirror, they will invariably stand or move their head to an angle that they feel makes them look their best. This is incredibly valuable knowledge. Try to find a camera angle that corresponds to the view they saw in the mirror.

People never stand or look straight when they look in a mirror. However, they walk onto a set and stand straight in front of a camera. Gently coax them to find the same position that they took in front of the mirror. Look carefully at the subject to find the most striking thing about him or her. In truth, I don’t think as much about hiding flaws as I do about accentuating the positive. Everyone has something great about their faces. It might be incredible cheekbones, a beautiful open smile, or piercing eyes. I just find something to love about them and build on that.

Lens Selection

For portraiture, it’s actually not about focal length—it’s about distance.

Most people start to look their best from about six to eight feet away. If you are including their entire body and parts of their surroundings, then go ahead and shoot with any focal length you want.

If you are shooting the classic head-and-shoulders portrait, then it’s simple. Use a focal length that is at least one and a half times the normal focal length. This mimics the view in the bathroom mirror and positions the camera at a comfortable, conversational distance. The corresponding focal lengths are at least 85 mm on a 35 mm camera or about 60 mm on a DSLR. If you can use (or have) a longer lens, then use it. The subject will just get more attractive as you move the camera away then use the lens to zoom in.

Remember the photos of the two globes we saw in Chapter 2? By using a longer lens and moving the camera back, the lens minimized or seemed to compress the distance between the two globes. The same thing happens with noses, ears, and foreheads. Shooting with a longer lens minimizes the spatial differences and yields a perspective that conforms to the subject’s self-image in the bathroom mirror.

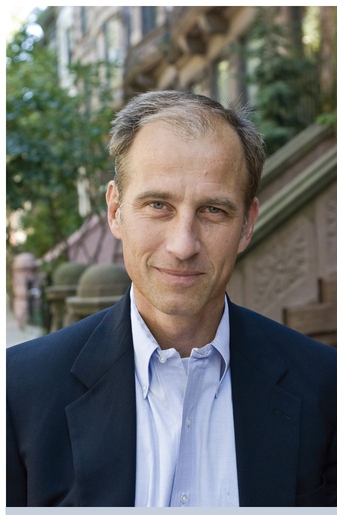

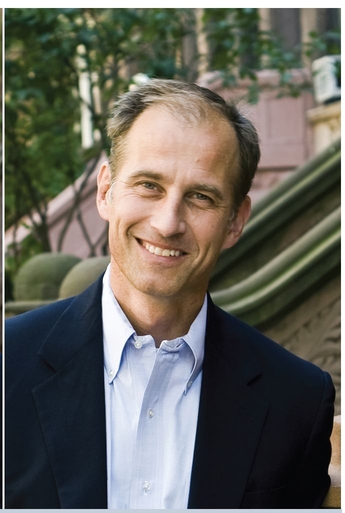

This guy is good looking, but look at how small and thin his neck looks in proportion to his nose and jaw. This photo was shot with a 32 mm lens, approximately “normal” on a DSLR.

Doubling the focal length and moving twice as far away (six to seven feet) results in the man appearing the way we see him at a normal conversational distance and the way he sees himself in the mirror. A longer lens would probably look even better.

The funny thing is that some people have faces that often look a little too angular and odd when you meet them in person. However, when viewed through the longer focal-length lenses, their faces “flatten out” and they become devastatingly attractive. We call these odd creatures “supermodels.” It’s the effect of the lens flattening the strong, exaggerated, and angular features that makes some people more photogenic than others.

Lighting for Portraits

Here’s another important reason why supermodels are who they are: facial symmetry. Their faces look very similar on both sides. If you look at most photographs of typical fashion models, the lighting is usually from a large but fairly hard source directly above the lens.

Models can look great with this kind of even and symmetrical lighting because it flattens the face and because their faces are very symmetrical. They can look great when lit with a pop-up flash directly over the lens.

Most of us are not so blessed. We might have broken noses or our jaw lines might be slightly different on each side of our faces. We’re not hideous, but the pop-up flash is brutal and really exaggerates the asymmetry of the average person’s face. This is the other big reason why people hate photos of themselves: the popup flash is a cruel light source.

It is also important to remember that lots of very attractive people have very asymmetrical faces. Actor Harrison Ford’s crooked smile hasn’t seemed to hurt him a bit. But you’ll also notice that he seldom gets lit from the front when he is facing the camera.

In everyday life, we seldom see ourselves with symmetrical lighting (remember what I said about the sun being the cue to lighting? ). The light is almost always stronger on one side than the other. Again, there are no rules to lighting any more than there are to composition—but there are some conventions that can be helpful, and we’ll explore those next.

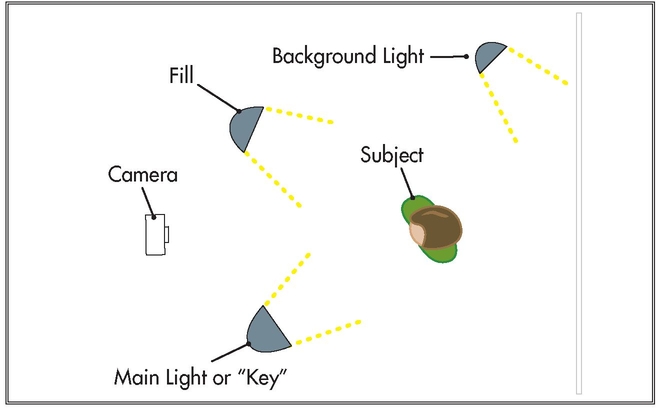

A Primer on Three-Point Lighting

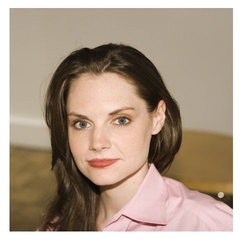

Think back to the last chapter and the first photograph where the young woman looked pasted onto the underexposed background.

Let’s call that one-point lighting (because all of the light was coming from one place: the pop-up flash). She looks pasted into the background because there was no secondary source to light the background and separate her from it. The light was contrasty because there was no fill to lighten up the shadows.

Three-point lighting is the mainstay of Hollywood. Virtually every frame you see in any film is some variation of three-point lighting. Modern film emulsions have changed the game a lot, but there are some strong principles at work in terms of how we look at people and space that continue to make the convention of three-point lighting compelling in the twenty-first century.

A fill is a light source (usually large, diffuse, and soft-edged) that reduces the contrast in shadows.

When you look at the classic photographs by George Hurrell of Marlene Dietrich, Lauren Bacall, and Humphrey Bogart, you are looking at a master of three-point lighting at work.

Here’s the basic formula:

In a classic three-point light scheme:

• The main light, or key light, is placed to one side. It is usually the strongest light on the set.

• The fill light comes from near the camera or just on the other side. It is usually a large and diffuse source. It should be so weak relative to the main light that it casts no shadows.

• The background light is positioned so that it throws light on the background and visually separates the subject from the background.

When it all goes together, it looks like this.

Now, I know what you’re thinking. “I don’t have three lights and a studio! I can’t do that with my camera!” But you can. I did this same basic thing to create the following photograph:

The main light was the flash bounced off the wall. The fill light was from the windows, and the background light was another window.

Now, you might think that I made the two photographs like that on purpose in order to demonstrate this point. I didn’t. The “flash-on-camera” photograph was simply made to illustrate how to mix flash and available light. I composed the photos on pure instinct. It was only when I looked at them later that I realized the similarity, which proves the point about how strong the underlying principles are in three-point lighting. Once you know what it is, you will notice it in virtually every photo you see in magazines and movies.

There are hundreds of variations on this basic setup: the background light could face forward and backlight the subject; the fill can be bounced off the ceiling or even eliminated; and so on. The lights can even be different color temperatures. It’s like a pool table with a million possible shots depending on the relative location of each ball.

The basic three-point formula also applies to different races and ethnicities. There are some subtleties to the amount and strength of the fill light, but three-point lighting isn’t about skin color or complexion as much as it’s about defining the architecture of the facial structure (the bones) and the space the subject is in. Denzel Washington gets the same basic light as Harrison Ford because their bone structures are very similar.

Three-point lighting is the mainstay of Hollywood. It is also the formula for tacky high school yearbook photography. Your skill and sensitivity separate the two, however. As the famous architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe said, “God is in the details.”

Context

I actually hate the tricks used to make people look “attractive.” It’s not what real portraiture is about. But with practice, it will become very easy for you to take photographs that make people look good.

Not everyone is beautiful, but everyone is interesting. Everyone has a story and a passion. The real challenge of portraits is to make the viewer interested in the person you are photographing.

When we look at photographs of celebrities, they come with their own context. We know who they are, and that is why we are interested. When we see a photo of the president picking his nose or a pop star leaving a club, it is only interesting because of the person’s public persona. Photographing ordinary people who are unknown is a bigger challenge in many ways because the photographer has to show and explain to the viewer why the person who has been photographed is interesting.

If only you could somehow show more than just the person’s face … now things could get interesting.

Photographs that show a person’s surroundings and tell us about the person through his or her possessions or situation are commonly known in the business as “environmental portraits.” Some photographers like Annie Leibovitz, Mark Seliger, and the late great Arnold Newman have built their careers on the environmental portrait.

If you think about it, most of the photos you make are probably some form of environmental portrait: “Here’s my wife after her first triathlon” or, “Here’s my kid on our vacation.”

Almost all common snapshots are somehow built around giving the subject some form of context or story. We do this largely on instinct. The problem with photographs like the one earlier is that they have nothing to interest a viewer who isn’t emotionally connected to the subject. The missing ingredient is something that is visually compelling—some kind of visual “oomph.”

Now, I could take the easy road and say, “Don’t ask me what oomph is—but I know it when I see it!”. But that wouldn’t be very instructive.

It might be one or many things: the camera angle, the lighting, and/or the pose and beauty of the subject. I think one thing it might be is a visual surprise of some kind—something that is odd or unexpected that hooks the viewer into the photograph. Another element might be universality—something that takes the viewer beyond the specifics of the person and situation being photographed.

The interesting thing is that the “universal” is usually accomplished by being extremely specific. This is really the key to all great portraiture, from Diane Arbus to Annie Leibovitz. Somehow, the more specific a photograph is, the more universal it becomes.

Bringing the idea of context and situation into your photographs can make a huge impact on the “staying power” of your portraits.

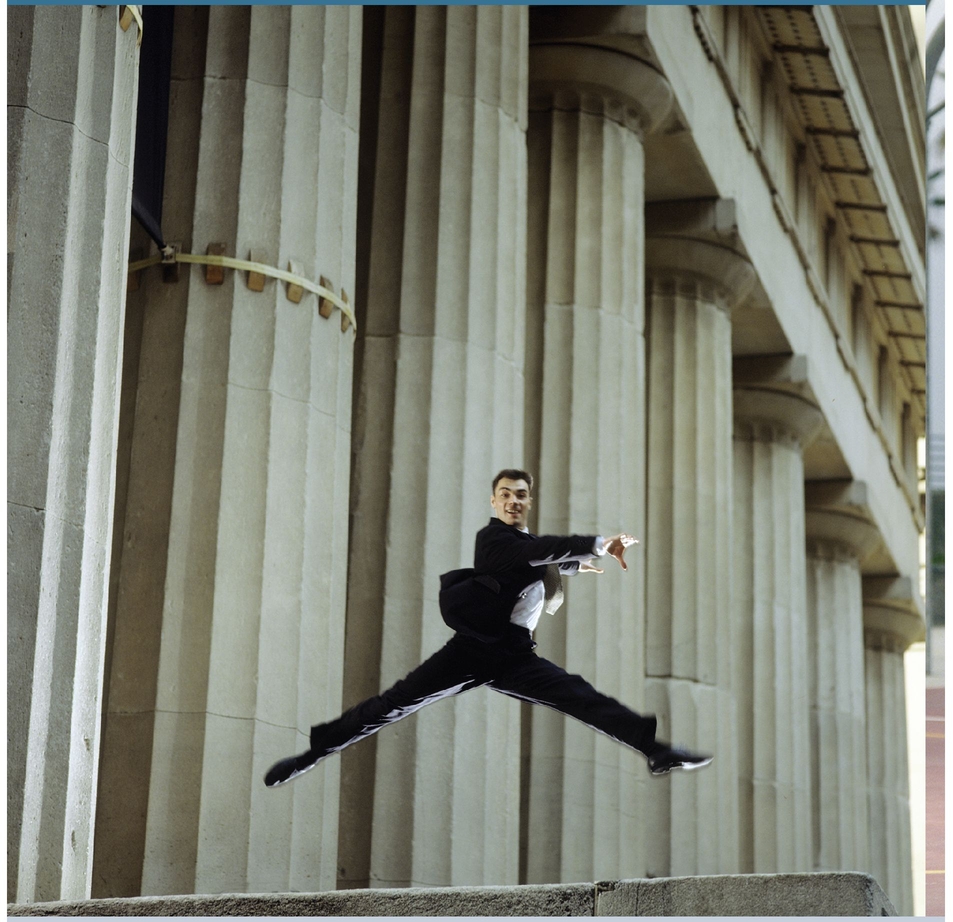

Case Study: The Environmental Portrait

This portrait of a dancer doesn’t need the surroundings to establish context. His body supplies all the information we need to know about what he does. This freed me to use an unusual location as the “odd” element.

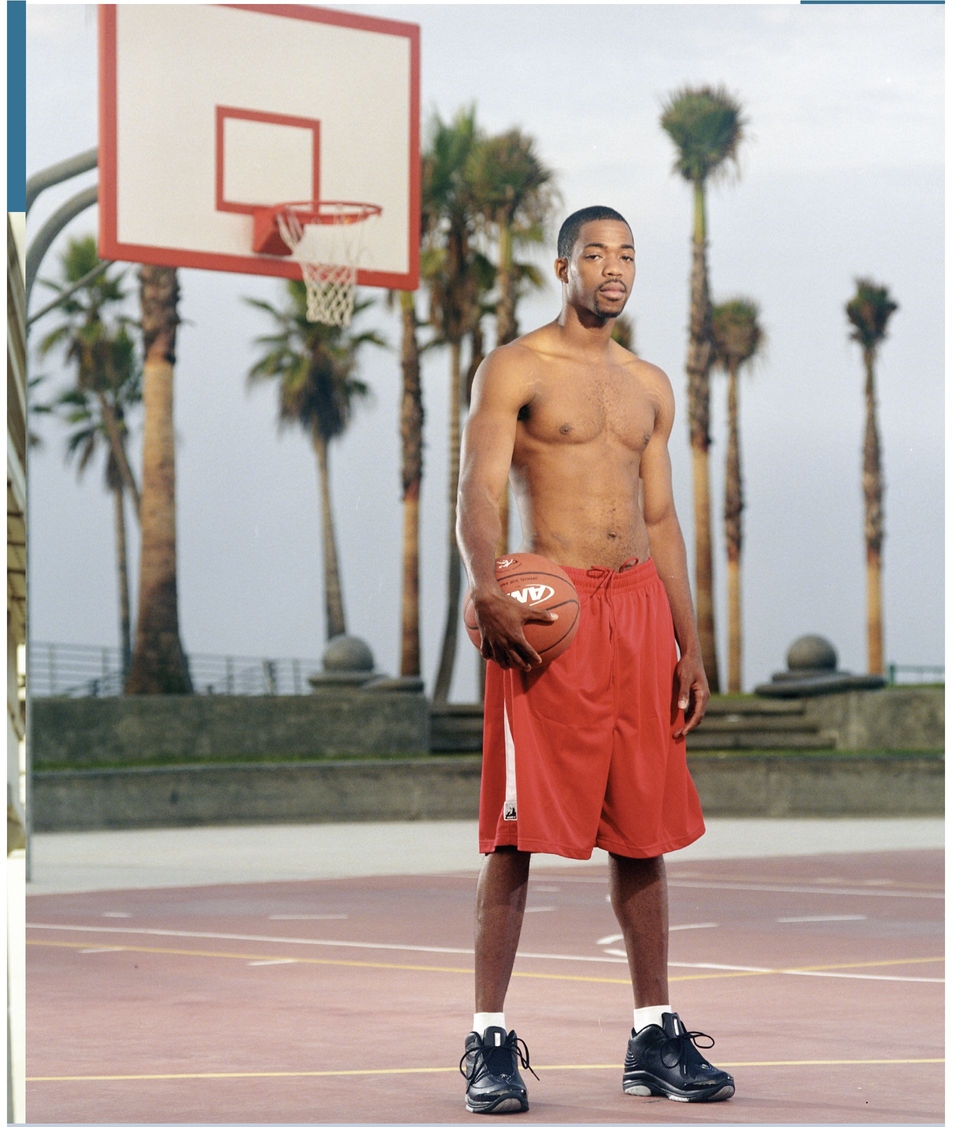

Having a cooperative subject is a huge help. For this portrait of NBA star Rafer “Skip to My Lou” Alston, I relied on using the sun as my background light. Lighting was set up at 4 A.M. for a sunrise shoot. Alston was a good sport and graciously arrived before dawn in order to catch the early light.

Candid Photographs of People

Candid photographs of people should be the easiest photographs to make, but this is the one area where I think the kit zoom lens and Program mode really hurt amateur photographers.

The problem is that the zoom lens doesn’t have a very wide aperture. This isn’t a big deal outdoors, but it’s a real problem when you are inside and want to remain unobtrusive. At the long end of the lens’s zoom range, the maximum aperture is only about f/5.6 for most kit zooms. Even if you crank the ISO up to 800, the maximum aperture of f/5.6 is still very slow for available-light photography indoors. If your camera is set to Auto mode, the flash is going to pop up automatically on most cameras. It’s pretty hard to be unobtrusive when the flash is going off all the time. If the shutter click is a subtle, audible signal to the subject about a judgment you have made, the flash is a giant blinking neon sign. If you like shooting candidly, then at least one really fast lens with a large maximum aperture (like a 50 mm, f/1.8) is a good investment and very inexpensive.

There is a really great way to get people to forget that you are shooting (and making judgments about them) that is a little surprising: shoot a lot. A whole lot. Shoot so much that they can’t keep track of it all.

Think about it. In the early days of photography, having a photograph taken was a major event. People rented clothes just to be photographed. There was a lot riding on every single exposure.

Shooting a lot of photos when you are trying to shoot candid photographs makes every photograph seem less important to the subject and might help him or her feel less self-conscious. But it can also backfire, so be careful.

Pro Tip

Smile. It tells people that you like them. When I am on an assignment that requires shooting candid photos of people I don’t know, I am often greeted with a hard, angry glare when the subject realizes I have been shooting him or her. Just lower the camera, smile, and say, “You looked great!” It works every time as long as it’s a true statement (and it usually is).

Point of View in Candid Photography

I am often hired to be a fly on the wall for commercial and photojournalism assignments, but many of my magazine assignments are stories that I am writing as well—usually in the form of a first-person narrative.

Whatever the assignment is, the photographs have to reflect the differences in the photographer’s point of view. Amateurs really never think about this; neither do a lot of pros. When we read a book, the author has always made a fundamental choice to write in either first person or third person. It’s either, “I watched the killer come closer” or “The killer stalked the unsuspecting victim.” As a photographer, whether you know it or not, you are always choosing between the two.

People FAQs

How do I stay inconspicuous when I shoot candid photographs?

The traditional answer to this question is to shoot with a very long focal length lens, but I couldn’t disagree more.

Long lenses actually limit your ability to move around a subject and change your vantage point because you have to move so far in order to make comparatively small changes to the composition. You can end up circling around the subject like a bird of prey and actually draw more attention to yourself. You are also pointing a very large and threatening lens at them. When you look carefully at the work of great photojournalists it’s pretty apparent that the long lens is usually a last resort.

I find that by shooting with very wide lenses I am able to move closer and then I simply pretend to be shooting something else. I then focus on an object that is about the same distance as my intended subject (the pro term for this technique is “surrogate focusing”) and then watch my subject with my other eye (or keep them in view at the very edge of the frame). When the moment is right you just swing into the final composition. This technique also tends to reinforce the first person point-of-view.

Another technique is to simply not look through the lens and just shoot from the hip. With some practice it is very easy to visualize the final photo without ever looking through the camera. You see photojournalists do this all the time in crowded situations (like holding the camera overhead) and they know to a very high degree of certainty exactly what they will get.

How do I get people to smile comfortably for portraits?

Professional models know how to perform for every frame, and this ability makes them worth every cent they make. Ordinary people need some help and it’s our job to help them.

Sitting for a portrait is an almost hypnotic experience; I’ll break up the session momentarily when I see the subject start to glaze over or I see the smile become frozen. I’ll tell them to take a five second stroll around the set, or have grimace and make faces to loosen up their facial muscles. The little breaks really help them to feel comfortable in front of the camera. Encouraging them to do something that feels silly (like making a big goofy face) can often really help them to relax.

Photosensitive

Whatever you do, don’t tell them a joke! I have never seen this work, for me, or any other photographer. At best you get a momentary guffaw, more often it’s a condescending smirk.

Case Study: Point of View

Here are some photos that reflect different points of view.

This photo has most of the signature elements of candid photography. The subject is unaware and although it is shot with a long lens, I still used surrogate focusing in order to avoid pointing the lens at him for a prolonged period of time. People seem to be able to sense a camera trained on them no matter how far away you are.

For my Baja story, I wanted to give the readers a feel for what the racers experience from the rider’s point of view. I borrowed a race bike from the Honda Team and followed Honda factory rider Steve Hengeveld on one of his practice runs.

I used a relatively slow shutter speed of 1⁄30th of a second at f/22 to exaggerate the frantic effect of motion. There was no place to mount the camera, so I just hung it around my neck and guessed at the angle of view. The camera was fired by a remote release taped to my left hand.

I swear that I didn’t set this one up. One of the classic elements that reinforces the omniscient, third-person point of view is the “dirty frame.” In this case, it’s the motion of the car going past.

The first-person point of view acknowledges the presence of the photographer and the camera. Even kids who are photographed every day can get a little annoyed.

Like all good art, photographs of people need to be decisive and strongly reflect a particular point of view.

The Least You Need to Know

• Portraits that offer insight into the person are more effective and interesting than photos that simply describe a face.

• Understanding how subjects view themselves is important in making photographs that will be pleasing to both of you.

• Learning to use light well makes your portraits stronger.

• Establishing a distinct point of view helps strengthen your photographs.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.