CHAPTER ELEVEN

MODEL #8: THE SOCIAL STYLE1 MODEL

BACKGROUND OF THE SOCIAL STYLE MODEL

One of the most common framings of conflict is the ubiquitous “personality conflict.” Personality conflicts seem to abound, yet there is very little consistency or common understanding about what personality conflict is or what should be done about it. There are a wide variety of models that attempt to assess different personality traits and give guidance on what can be done about the different personalities that are encountered in the world. Most of these models tend to be focused on the idea of communication styles.

Communication, and the quality of our communication processes, are central to the experience of conflict. For conflict practitioners, therefore, having a workable model to assist with personality and communication issues is important.

The most commonly known and referenced system for assessing personality traits is the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI)2. Much has been written on the Myers-Briggs model; hundreds of thousands of people have taken the MBTI assessment, creating a large database of statistical trends and analysis.

There is one significant drawback to using the MBTI system as a conflict practitioner, however: The MBTI model is based on how a person internally approaches processing and communicating information, and these internal processes are extremely hard to observe. The most common way MBTI is used is to have individuals fill out the MBTI assessment tool (a type of questionnaire) that assesses and categorizes the individual's personality and information-processing traits. The results from this assessment are then made available to the individual or the work group. This means that, for the MBTI to be useful in a conflict situation, the mediator or practitioner would need to ask parties to fill out a whole questionnaire before the intervention. Although this may not be completely out of the question, it severely limits the usefulness of the model.

In looking for an individual style-based analysis model, therefore, a more effective tool would be a model that assessed personality based on observable behavior, not internal processes. The Social Style model fits this requirement.

The Social Style model3 is another style model that comes from the same roots as the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, with two significant differences. First, the Social Style approach is focused on an individual's observable behavior, not their internal processes. This means that observable behavior can help the practitioner assess the predominant “style” of the people in the dispute and can make intervention decisions based on that assessment. Formal instruments and questionnaires do exist for assessing behavioral style under the Social Style model, with one significant difference; because observable behavior is the basis of the model, the Social Style assessment relies more on peer assessment and less on individual self-assessment. In addition, the formal use of questionnaires, whether self or peer, is not required to make effective use of the Social Style model-it can be useful to a practitioner by simply observing the behavior of the parties.

Second, the Social Style model is much simpler. The Social Style model relies on and assesses two dimensions of behavior—assertiveness and emotional responsiveness. This produces four possible “styles” or types. By comparison, the MBTI works with four different dimensions, which produces 16 different types, a far more complex model to work with. Social Style, therefore, is more functional and effective for practitioners in the conflict and dispute resolution field.

DIAGNOSIS WITH THE SOCIAL STYLE MODEL

In terms of diagnostic assessment using the Social Style model, the first step is to identify the styles of the people involved. This requires direct observation of the parties' behavior, which is done by looking for indicators along two broad dimensions of human behavior, assertiveness and responsiveness.

Assertiveness is defined as “the degree to which others perceive a person as tending to ask or tell in interactions with others.” People who are more reserved, tentative, and who tend to keep their thoughts to themselves are “ask” assertive, whereas those who are more forceful and direct in their interactions are “tell” assertive. The model recognizes that people, in general, try to get what they want, and this dimension measures whether they do this with a more “ask” assertive or more “tell” assertive approach.

Responsiveness is defined as “the degree to which others perceive a person as tending to control or display their emotions when interacting.” Individuals who are more controlled do not typically display much emotion when interacting. They tend to be concerned with getting things done in a no-nonsense manner, and tend to be more distant and formal. Those people with an emoting disposition display their emotions more readily to others and are characterized by their relatively casual manner. These individuals like to get involved with others on a personal basis.

Both dimensions have specific, observable behaviors that give clear indicators of where a person fits on the particular scale.

Indicators of Assertiveness

| Ask Assertive | Tell Assertive | |

| Less | Amount of Talking | More |

| Slower | Rate of Speaking | Faster |

| Softer | Voice Volume | Louder |

| Less, slower | Body Movement | More, faster |

| Indirect | Eye Contact | Direct |

| Leans back | Posture | Leans forward |

| Less | Forcefulness of Gestures | More |

Tell assertive individuals tend to talk more, talk louder, speak at a faster pace, tend to move faster, lean forward, and use forceful gestures. Overall, they tend to demonstrate higher energy. Ask assertive people tend to speak less often, slower, and softer; they tend to move slower, lean back, and gesture with less emphasis, if they gesture at all.

Indicators of Responsiveness

| Control Responsive | Emote Responsive | |

| Controlled | Facial Animation | Animated |

| Monotone | Vocal Animation and Variance | Inflection |

| Restrained, few gestures or facial expressions | Physical Animation | Animated, strong use of physical gestures, such as hands and facial expressions |

| Rigid | Posture | Casual |

| Tasks | Subjects of Speech | People |

| Facts & Data | Focus | Opinions & Stories |

| Less | Use of Hands | More |

Emote responsive people are more animated physically and facially and use smooth, flowing gestures. They show their own feelings and acknowledge other people's feelings more often. Control responsive people4 are less animated, they gesture less, and they don't tend to acknowledge their own or other people's feelings.

The four social styles

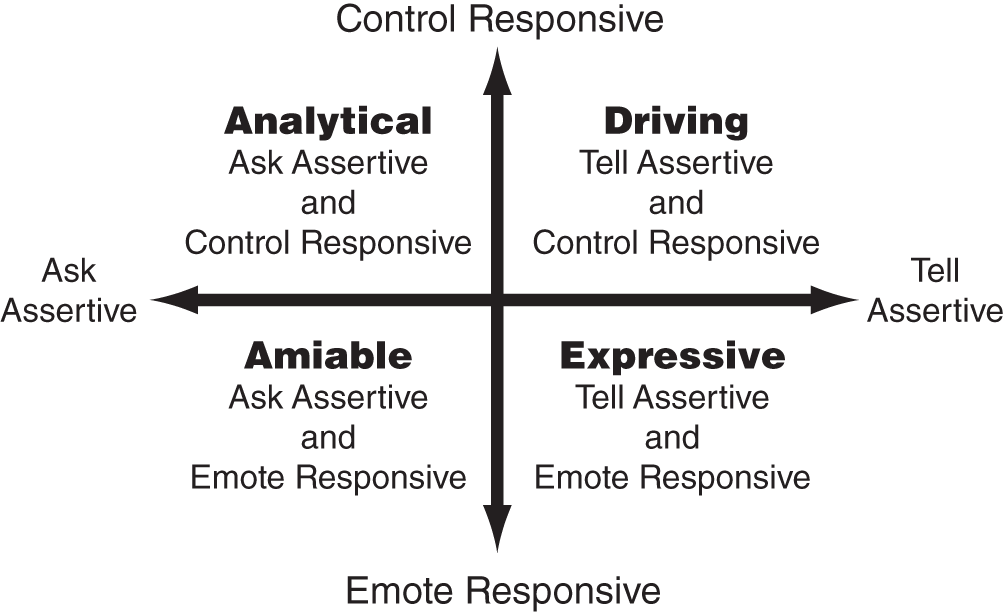

Once the practitioner has assessed the parties in terms of the assertiveness and responsiveness indicators, he or she can set the two dimensions together on a grid. This produces four quadrants or “styles” of behavior, as shown in Figure 11.1.

- Analytical Style: Analytical Style people are more ask assertive than 50% of the population and more control responsive than 50% of the population.

- Driving Style: Driving Style people are more tell assertive than 50% of the population and more control responsive than 50% of the population.

- Expressive Style: Expressive Style people are more tell assertive than 50% of the population and more emote responsive than 50% of the population.

- Amiable Style: Amiable Style people are more ask assertive than 50% of the population, and more emote responsive than 50% of the population.

Figure 11.1 Social Style model: Diagnosis

Based on the dimensions of assertiveness and responsiveness, and on the characteristics and interrelationships of these dimensions, the four Social Style groups have different qualities and tendencies identified in the following ways:

Characteristics of the Four Styles

| Analytical Characteristics: Prudent Task Oriented Detail Focused Slow, Careful Decision Makers Logical Low Key |

Driving Characteristics: Independent Task Oriented Results Oriented Decisive Fast-Paced Dominating |

| Amiable Characteristics: Dependable Relationship Oriented Supportive Confrontation Averse Open Flexible |

Expressive Characteristics: Visionary Animated Flamboyant High Energy, Fast-Paced Impulsive Opinionated |

Once the practitioner understands the predominant style of the people involved and locates them in one of the quadrants, he or she can then begin assessing the problems or causes of the conflict.

The Social Style model focuses on communication problems that can result from a clash of these styles. It shows that conflict is frequently caused by a mismatch in the styles themselves, not solely from the content of the problem. For example, if two individuals are working together on a project, one with a Driving style and the other an Amiable style, some of the key style differences may clash. The Driving style may be strongly task focused and quick to make decisions to move the project ahead, regardless of any feathers that might get ruffled in the process. The Amiable style, on the other hand, may balk at the decisions proposed, wanting to get buy-in from the people affected first, because people with an Amiable style tend to be focused on the relationships involved to a much greater degree than those with a Driving style. This may create and escalate a workplace conflict, regardless of the actual project decisions or outcomes themselves.

The Social Style model is also based on the assumption that personal styles are unconsciously learned, meaning that as we learn and grow we get comfortable with our predominant style, and we do this without being able to choose it. It simply becomes a core part of how we conduct ourselves. It is also based on the assumption that our predominant style is substantially permanent. This means that our “personality,” our core behavioral style, is unlikely to change. In some ways our style is like our native language—it is typically our most comfortable means of communication even if we learn other languages later in life.

Let's take a look at how the Social Style model can help in conflict situations.

CASE STUDY: SOCIAL STYLE DIAGNOSIS

The first step in our case study is to assess the Social Style of the people involved. The following is a description and assessment of the three parties.

- Bob: Bob was a very quiet, soft-spoken man who gravitated to very detail-oriented tasks such as accounting and record keeping. He spoke slowly, thought carefully before answering, and appeared very even tempered and low key. He spoke in a very quiet monotone with little expression and tended to look down when he spoke, moving little. Even when angry, Bob's expression was virtually unchanged. Based on these observations, a practitioner could conclude that he was ask assertive and control responsive, placing him as a strong Analytical.

- Sally: Sally was a high-energy individual who loved to describe the “big picture,” where she was leading the department, and how excited she was about the benefits of where they were headed. She spoke quickly, used her hands when she spoke, and often drew pictures on a flip chart to illustrate her point. Although not particularly argumentative, she often revisited points of disagreement to insist that her assessment made sense. She leaned forward when she spoke and often waited for the other person's reaction to what she said to confirm that they “got” her point, only then moving on to the next point. She was easy to read in terms of how she felt and tended to be positive and upbeat in general. She scored as emote responsive and tell assertive, placing her solidly in the Expressive category.

- Diane: Diane was also quiet but focused and to the point. She didn't speak very much, but when she did it was firm and clear. She made her points succinctly and expected a quick response to them. Her sentences were short and very action focused, such as “Please do this,” or “That's fine, do that.” She spoke little about how she felt and focused on the task at hand. She didn't like beating around the bush and would rather do a task than talk about it. She didn't understand why people couldn't simply get the job done and move on. She rated as tell assertive and control responsive, placing her in the Driving style.

Based on this assessment, it became clear that one aspect of the conflict was a significant communication problem. Bob complained that Sally never listened, talked over him, interrupted him, and didn't give him time to express himself. Sally complained that Bob didn't respond at all, that she would ask him a question and he would sit there and just stare at her. She would then continue talking because he didn't seem to be willing to. A significant part of the problem was their communication patterns and personal styles.

Between Bob and Diane, the problems were fewer, but still there. Diane found Bob to be slow and almost incapable of making decisions. Diane would ask him to do something and he would seem to agree, but then days later he would raise some well-thought-out objections, thus delaying the task far too long. Bob found Diane to be pushy and demanding and often rash in her decisions. He felt he was acting responsibly by raising problems before pressing forward and doing the task, and didn't understand why this upset her. On the other hand, both Bob and Diane were detail oriented and liked the feeling of finishing tasks and projects, and on that front, they worked well together.

As this analysis shows, both relationships suffered from a poor communication process caused by a significant difference in styles, or what we often refer to as “personality.” A practitioner diagnosing the conflict from this perspective can also learn and apply some effective interventions drawn from the Social Style model.

STRATEGIC DIRECTION FROM THE SOCIAL STYLE MODEL

Strategically, the Social Style model suggests three important interventions once the diagnosis is complete:

- Be versatile and flexible—change your style toward the other person's style to make them more comfortable.

- Translate the communication of one party into your style (or the style of another party, as appropriate).

- When functioning as a third party, coach each person on how to change their style when they communicate with people of different styles.

Versatility—Working well with all styles

A core concept in intervening using this model is the idea of “versatility.” It is by being flexible in our behavior that we can improve communications, and the Social Style model offers two ways to improve our versatility:

- First, we can all use behaviors from all four styles in different situations and circumstances. Human beings do not fit neatly into simple boxes and stay there. We respond in a variety of ways to the various situations we encounter, and we regularly use a range of styles and skills.

- Second, everyone has a favorite or predominant style that they spend a lot of time using, a style that they are most comfortable with. This is their “home base,” the style in which they will best hear and understand other people's communications.

To go back to our analogy of language, our predominant style is our native tongue, the one we are most comfortable with. That said, many people become fluent in second and third languages, which greatly expands their ability to communicate in the world. When two people meet, one who speaks three languages and one only their native language, it makes sense for both to speak the common language rather than each insisting on speaking their own native tongue. In other words, one person needs to do something for the other person and agree to speak the other's language in order to facilitate their communication. The idea behind being versatile with Social Styles is that the other party will be able to hear and understand the communication better if the content is presented in a style that is similar to their own.

In situations where a problem is arising not necessarily because of the content itself, but because the content is getting lost or distorted due to a personality problem or a style conflict, we can change our communication style and choose behaviors that will make others more comfortable. Doing this will allow us to be better heard and received.

This idea of versatility or “doing something for others” is already implicit in our society and culture to a great degree and should not be seen as a new or foreign concept. For example, when talking to someone who has just recently learned English, we tend to slow down, speak a bit clearer, and perhaps choose language that will be easier for a new speaker of the language to understand. When we are speaking to a non-technical person about a technical issue, we will try to make it clearer for the other person by using less technical jargon. In the same way, if we are an Expressive and we know the other person is an Analytical, we should present our message in a style that an Analytical can best hear and understand; in addition, we should decode what the Analytical is saying to better understand it from an Expressive's point of view.

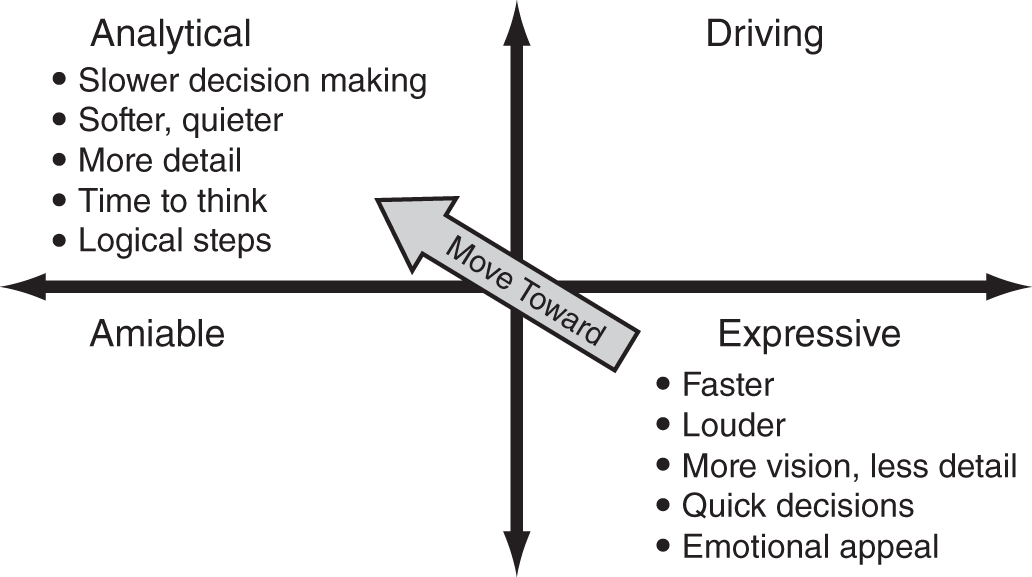

So what exactly is versatility? As Figure 11.2 shows, shifting from Expressive behaviors to Analytical behaviors would entail choices like speaking slower and quieter, using more hard data or information, presenting logical steps rather than emotional appeals, paying attention to details, and giving the Analytical a bit more time to process the information and come back later with questions. The net result of these behavioral changes is that the speaker's message is clearly delivered, eliminating resistance and conflict caused by a communication style or personality getting in the way.

Figure 11.2 Social Style model: Strategic guidance

Style versatility is primarily a behavioral change, and the following four behaviors are the most important to adjust, as appropriate to the circumstances.

Adjust your style in stages:

- Pace: Faster or Slower

- Detail/Structure: More or Less

- Small talk: More or Less

- Focus: Facts or Feelings

For all four styles, a brief indicator of the type of versatility choices that might help follows.

Amiables Working With:

Analyticals:

|

Drivers:

|

Amiables:

|

Expressives:

|

Drivers Working With:

Analyticals:

|

Drivers:

|

Amiables:

|

Expressives:

|

Expressives Working With:

Analyticals:

|

Drivers:

|

Amiables:

|

Expressives:

|

Analyticals Working With:

Analyticals:

|

Drivers:

|

Amiables:

|

Expressives:

|

By becoming versatile, the practitioner can greatly reduce resistance and friction in the communication system.

Translating and coaching the Social Style model

Another way a practitioner can help parties in a conflict is to assist by translating one person's communication from their predominant style into the other person's predominant style, using a variety of skills such as restating, reframing, paraphrasing, or changing the pacing, tone, and intensity. In this case, translating involves a great degree of versatility on the part of the translator, in that they need to be able to reach out across a whole range of styles; the speaker's style may be different from the receiver's style, both of which may be different from the translator's style.

In mediation or negotiation, for example, when all parties are present, it may be necessary to translate one party's style into a style that helps the other party to hear and understand. In one case, a strong Analytical lawyer began a joint session with a long explanation about what they liked and didn't like about the other party's most recent offer. Opposing counsel was a Driving style and was getting visibly more and more agitated the longer the Analytical spoke. The mediator gently intervened, asking, “At the end of the day, what are you recommending about their last offer?” The Analytical, looking surprised, said, “Well, we're accepting it, of course, but I thought you needed to know why.” The Driver stood up, offered his hand, and said, “All I need is a signed agreement.” The Analytical, in this case, had almost blown an agreement by staying stuck in his own style. In regard to coaching, the practitioner may be in the position of helping one party adapt their behavior to be better heard by the other side. In many negotiations or mediations, the practitioner will have each party describe and explain their issues directly to the other party. In caucus, the practitioner may well coach or prep one party to modify their presentation to make it more effective. For example, if a Driver is presenting to an Amiable, they may need to address the relationship issues (something someone with a Driving style may simply not think of), rather than just focus on the money or the task.

CASE STUDY: SOCIAL STYLE STRATEGIC DIRECTION

In our case study, there would need to be two interventions, one between Sally and Bob and a second between Bob and Diane. What follows is how a mediator might apply these interventions with the parties.

Sally and Bob

This meeting required a significant amount of versatility of the mediator. Because of her role as the manager, as well as the fact that Bob appeared less flexible than Sally, the mediator focused on helping Sally do the majority of the style adapting. Prior to the meeting, the mediator met with Sally and shared the concept of versatility with her. Sally stated that she was willing to try if it would help. The mediator coached Sally to slow down, focus on data and logic, give Bob time to digest and think about what was said, and not force quick decisions. In addition, the mediator coached Bob to ask for time to think rather than just go silent. During the meeting, the mediator helped both parties translate back and forth from the Analytical to the Expressive when needed. The result was a very productive meeting during which Bob heard and considered some key information for the first time (the fact that the structural changes were nationwide, for example, and the reasons why seniority wasn't considered in the promotion), and Sally heard how hard it was for Bob to feel like his last 12 years didn't count for anything when he had helped manage so much of the paperwork in that office. This greatly improved their ability to hear each other and allowed them to focus on solving each other's problem the first time they had ever reached the point of problem solving together. Bob even surprised Sally by saying that he didn't need time to go away to think about the discussion; he was prepared to stand by the decisions they had made that day. After the meeting, both Sally and Bob spoke to the mediator privately and wondered aloud what had made the “other person change so much.”

Diane and Bob

This meeting involved a very similar process, except that the mediator decided that neither would benefit from coaching ahead of time and spent most of the meeting translating between the Driver (Diane) and the Analytical (Bob). The main point of contention in their communication process was how work would be assigned, followed up, and completed. Diane, who had a Driving style, was most comfortable telling Bob what to do and giving him orders. As an Analytical, Bob wanted time to mull over a problem before agreeing to the decision. In the end, both parties made changes for the other—Bob accepting orders on the simple and obvious tasks, and Diane accepting that Bob would need time to think about and raise issues on the more complex tasks. Because both were task oriented, they quickly agreed to develop a written description detailing exactly how various situations would be handled between them.

In both cases, the practitioner followed the strategic direction of the model:

- The mediator adapted her style toward each of the other parties' styles when communicating with them.

- The mediator translated the communications of one party into the style of the other party.

- The mediator coached Sally and Bob on how to change their style when they communicated with each other.

ASSESSING AND APPLYING THE SOCIAL STYLE MODEL

The Social Style model is broadly applicable to many conflicts in that it applies to the personality and communication part of the conflict process. It is not as directly helpful in other aspects of conflict where structural or substantive issues are the main barriers, as the model doesn't work directly with the content of any given situation.

Diagnostically, the model is useful but somewhat limited in its range of use because it diagnoses only conflict that is generated from communications problems. This ranks it as a medium on the diagnostic scale.

Strategically, the model directs a practitioner to make simple changes to his or her communication patterns in order to help with personality and communication issues. It ranks medium to high on the strategic scale.

Final thoughts on the Social Style model

Overall, the Social Style model ranks high in importance, in that all practitioners need a framework for addressing personality and communication conflicts in order to be effective when working with a wide range of clients. The whole area of personality conflict and communication issues within conflict is complex and detailed, making personality-related conflict one of the hardest areas to address. The Social Style model is one of the simplest and most effective models for tackling this and therefore is one of the most important tools a practitioner can have.

PRACTITIONER'S WORKSHEET FOR THE SOCIAL STYLE MODEL

- Assess the individuals along both dimensions, assertiveness and responsiveness.

| Ask Assertive | Tell Assertive | |

| Less | Amount of Talking | More |

| Slower | Rate of Speaking | Faster |

| Softer | Voice Volume | Louder |

| Less, Slower | Body Movement | More, Faster |

| Indirect | Eye Contact | Direct |

| Leans back | Posture | Leans forward |

| Less | Forcefulness of Gestures | More |

| Control Responsive | Emote Responsive | |

| Controlled | Facial Animation | Animated |

| Monotone | Vocal Animation | Inflection |

| Restrained, few gestures or facial expressions | Physical Animation and Variance | Animated, strong use of physical gestures such as hands and facial expressions |

| Rigid | Body Posture | Casual |

| Tasks | Subjects of Speech | People |

| Facts & Data | Focus | Opinions & Stories |

| Less | Use of Hands | More |

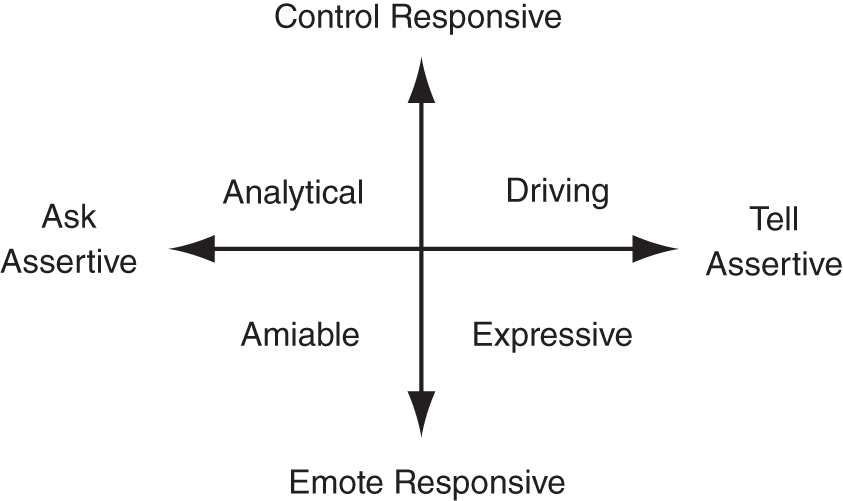

- Place the individuals into a quadrant on the grid in Figure 11.3.

- Assess what strategies will help, and where they should be applied.

Where will versatility help? What steps can be taken to adapt to other styles?

Figure 11.3 Styles of people involved

| Pace: Faster or Slower? |

| Detail and Structure: More or Less? |

| Small Talk: More or Less? |

| Focus: Facts or Feelings? |

| Where will translating help? Between which parties? |

| Where will coaching help? With which parties? |

ADDITIONAL CASE STUDY: SOCIAL STYLE MODEL

Case Study: The Vision Thing

A small start-up company that delivered services in a very technical area of the financial services field was experiencing a significant amount of conflict. The company had 35 staff, including five supervisors, two directors, and the chief executive officer. In the two years they'd been in business the company had been very successful, and the CEO was committed to an “open” management style. He met with the entire staff twice a year, each time sharing the status of the company in relation to the business plan and how the company was doing. He often painted a clear picture and vision for where the company was going.

About six months after the initial staff were hired, there was some grumbling about not being able to trust the CEO and concerns about the direction of the company. Initially the CEO ignored the grumbling, but it continued to grow. The CEO asked his management team to communicate more with the staff, to reiterate the vision and direction, but the issue seemed to get worse. The CEO arranged another town hall, once again articulated the direction and goals of the company, and again thought that he had gotten through to the staff. The dissent, however, continued to grow and became a significant drain on morale in the company. The CEO didn't know what to do but continued meeting with the staff as much as possible to reassure them and talk about the future of the company. The decline in morale, however, continued.

To turn things around, the CEO once again held a town hall meeting, trying to rally the staff and get them refocused on the future and the goals of the company. It didn't help. Three staff members quit to take other positions, and there was a widespread feeling that this was no longer a good place to work.

Social Style model diagnosis: The Vision Thing

The management team decided to do a large-scale intervention and brought in consultants who recommended the use of the Social Style instrument. Everyone in the company was assessed by three peers, up to and including the CEO. The results were startling. Of the 35 staff, the styles broke down this way:

- Amiables – 2

- Drivers – 5

- Analyticals – 27

- Expressives – 1

Even more interesting was the breakdown of roles in the company among those with different styles. Of the five supervisors, three were Drivers and two were Analyticals. Of the two directors, one was Amiable, the other a Driver. The lone Expressive was the CEO.

This information was shared at a full company retreat, immediately revealing a major source of the dissatisfaction and conflict. It became clear that what was missing was not communication in general (as there was plenty of that) but rather a specific type of communication. The Analyticals were missing a significant amount of detail and structure about the company plans and directions, information that Analyticals typically need to feel comfortable and well informed. The CEO had correctly sensed that more communication was needed, but what he gave them was a broad vision for the future (something that Expressives focus on) rather than specific detail (which Analyticals tend to look for). This had the effect of convincing the Analyticals that the CEO didn't really know what he was doing, that he was blowing smoke rather than giving them concrete information about the short-term, tactical steps that would actually help achieve the vision. The more the CEO gave them the “big picture” rather than the tactics and details, the less they trusted him.

In addition, three of the supervisors were Drivers who had little patience for the type of information and decision-making time the Analyticals needed. When they asked for input from their teams, they rarely gave the staff enough time to give thoughtful responses, and consequently at least three of the teams felt railroaded by their supervisors.

It became clear that the style and quality of communication needed to be improved.

Social Style model strategic direction: The Vision Thing

The consultants asked the CEO these questions as to what should be done strategically to resolve the issues:

Epilogue of the case study

A year after the company retreat, a major change had occurred. Communication patterns had shifted significantly, guided by regular feedback from the staff. The CEO was happy, in that he felt his message was finally getting through. He had moments when he needed to walk through the vision once more, but he combined that with other communication approaches that met the staff's need for detail. Satisfaction levels had increased substantially, and the communication side of the surveys rated the company over 90% on “quality of staff communication.”

NOTES

- 1. Social Style is copyrighted material owned by The TRACOM Group and used here with permission.

- 2. I. B. Myers and M. H. McCaulley, A Guide to the Development and Use of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1985).

- 3. D. W. Merrill and R. H. Reid, Personal Styles & Effective Performance (CRC Press: Boca Raton, 1984).

- 4. It should be noted that in regard to responsiveness, control responsive people have just as many feelings as anyone else, and there is no implication otherwise. The only distinction is whether they allow those feelings to show or not.