Case 22. A Brazilian Dairy Cooperative: Transaction Cost Approach in a Supply Chain

† Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil; [email protected]

‡ Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil; [email protected]

Supply chain studies are important because a good management system and governance between its members can generate systematic earnings and competitive advantages for an entire supply chain. Therefore, understanding the way that a supply chain is structured and determining the main relations and transactions between its members are essential to making a critical analysis for systemic optimizations.

A cooperative supply chain has some extra peculiarity, based on its values of self-help, self-responsibility, democracy and equality, equity, and solidarity. In the Cooperativa Agropecuária Petrópolis Ltda. (COAPEL), a cooperative company (co-op) that operates in the Brazilian dairy industry, the managers have some doubts regarding the actions that need to be taken to achieve a better transaction efficiency to support the main activities of COAPEL’s supply chain and also to minimize risks within the supply chain.

This approach in this case includes a mapping of the co-op’s supply chain, the identification of its primary members, and a structural analysis of the chain. The findings presented here are based on transaction costs approach attributes and ways in which the management and the cooperative business model can influence them.

Background for the Cooperative and the Industry

COAPEL, commercially known as Piá (trademark of products), was founded in October 29, 1967, in the district of Vila Olinda in Nova Petrópolis in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, in the South region of Brazil. The co-op’s history started with a partnership between the German government and a group of 213 farmers in the region, with the goal of developing milk production in that area and seeking more price competitiveness for their dairy products. Another target of this project was to transform farmers into agricultural businessmen through professionalization, increasing their competitive edge with a better production environment and more efficient processes.

The co-op has grown, expanding its product mix and geographic reach. It currently operates in more than 80 cities in Rio Grande do Sul state, supported by the performance of its 15,000 members and revenues of 414 million Reais. The co-op represents 8.5% of dairy sales in the South Region of Brazil (Latin Panel data). The main focus of COAPEL is the Rio Grande do Sul market, representing 65%. In addition, Santa Catarina represents 20% and Paraná 15%. COAPEL usually buys milk from its members, but sometimes it will buy milk in the “spot market” when demand is higher than the supply that its members can provide. The supplier network includes both large and small farmers from the region.

Brazil is the fifth largest milk producer in the world, behind the USA, India, China, and Russia. The recent production levels represent a huge cycle of growth based on the introduction of UHT in the 1990s, changing the way of production and also manners of consumption. Investments flowed into this area, introducing technology and modernizing production with new techniques, machinery, and equipment. Milk consumption in Brazil remains low (15 kilos compared to 37 in Holland) but with better prospects due to the growth of population income and changes in diet.

The International Cooperative Alliance (ICA) provides the following definition: “A co-operative is an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social, and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically controlled enterprise.” A cooperative is also defined as a voluntary association of people, joining their production force, expenditures and, savings capacity to develop an economic and social business, generating to all members systematic gains (OCERGS, 2010). A co-op in this business model has its own values and principles. ICA has established seven principles for a co-op: voluntary and open membership; democratic member control; members’ economic participation; autonomy and independence; education, training and information; cooperation among different co-ops; and concern for community.

Cooperative relationships are based on co-op’s principles, giving emphasis to a long-term philosophy where everybody wins (Chistopherson and Coath, 2002). As a final point, some cooperatives’ doctrines, such as democracy, are useful for understanding the relationships between its members. For example, this relates to the manner in which a cooperative should be structured (administrative and management); the degree of free membership as well as free leaving; and the return of surplus capital, after deductions.

Transaction Costs Approach

The transaction costs approach, first studied by Ronald Coase in 1937 and further developed by Oliver Williamson in 1985, is the study of economic organizations, focusing on transactions and economic efforts to accomplish their activities. These transactions, according to Williamson (1985), occur when goods or services are transferred between different interfaces, having inherent process characteristics that determine the way that outputs are generated and how they are delivered to a customer. Costs are incurred for involved members to effect transactions, and internal costs accrue for each member. These relations and transactions are influenced by several factors, categorized by Williamson (1985) as behavioral and dimensional assumptions.

The behavioral assumptions focus on understanding the way that human nature works and also how the institutions work, such as laws and society, that shape these behaviors. Transaction costs related to behavioral factors include bounded rationality and opportunism of agents. Bounded rationality is related to cognitive limits of competence to formulate and solve complex problems where the knowledge of all variables is limited in a decision process, making it difficult for an agent to choose between different alternatives presented to him. Organizations try to avoid it with governance structures predicting and anticipating transactions in-house. It is also suggested as a way to increase rationality interactions between different agents as guidelines based on groups that can generate more efficient results than individual actions can (Simon, 1971, apud Gusmão, 2004). Opportunism of agents is related to the pursuit of self-interest to the detriment of others seeking their own benefits.

The dimensional assumptions are related to the way in which transactions are realized, with peculiarities of each organization. The main dimensions that describe a transaction are (1) asset specificity, which describes characteristics of an asset that express its specific value and usefulness; (2) uncertainty, which describes the future risks of a transaction related to its flows, difficult to be predicted and covered by contracts; and (3) frequency, which describes a transaction recurring between two agents.

COAPEL Supply Chain

COAPEL management hired a company to analyze the supply chain, and one of the first findings was its structure, as shown in Exhibit 22-1.

After a restructuring process at COAPEL over the past few years, its activities were subdivided into two units, main unit and support unit, to facilitate a better development of activities. The main unit is comprised of the dairy industry, input factories and distribution centers, agriculture retail, and consumer retail/supermarkets. The support unit includes technical assistance, controllership, marketing, human resources, etc.

The co-op management is professional, but engaging in permanent interactions with the co-op’s members through cooperative councils. In addition, COAPEL has a strategic guideline for management related to matters such as transparency, promotion of the co-op’s actions and principles, maximization of members’ benefits, and self-sufficiency, among others, based on the company’s bylaws. Also, the company is mainly run according to the cooperative’s principles, as evidenced in some of COAPEL’s practices, such as programs and benefits offered to its members.

In this supply chain, the main transactions are the frequent interactions between COAPEL and its cooperative associates. In these transactions, there are exchanges for both sides: farmers provide raw materials, fresh fruit, and milk, while the co-op buys their production and supports them with some benefits for this production and development of their land. To better manage the range of associates, COAPEL has subdivided them into five areas. However, this management process has some limitations, since there is no strict control of production receipt. In addition, there is no association or supply contract with the co-op and its associates. However, to join the cooperative the associates accept the norms and rules of the organization, which includes certain liabilities.

In conclusion, the co-op is socially efficient with strong performance by members in management, especially the farmers. In this supply chain, process flows are controlled by the main co-op, COAPEL, but management of the chain is shared among professionals and cooperative members through councils, with large farming associates acting more actively.

These farmers are also consumers of the co-op’s retail activities (supermarkets and inputs). In the retail business the company also has urban members, and these associates are managed according to their purchases, obtaining profit-sharing at the end of each year.

Focal Supply Chain Analysis

Because the main and more critical transactions in this supply chain occur between the co-op and its members, the consulting team’s analysis centered on the focal supply chain presented in Exhibit 22-2.

Some requirements to join COAPEL include being a person dedicated to agricultural activity on self-owned land, selling all production to the co-op, and agreeing not to engage in practices that can harm or conflict with the co-op’s activities. Individuals and entities not dedicated to agricultural activities, but who are interested in retail consumption, may also join.

COAPEL does not have a maximum membership limitation, but membership cannot fall below 20. The association process is completed by filling out a membership proposal—there are no formal contracts in this relationship. The entrance of a new member must be approved by the COAPEL Board of Directors, and, if there are no restrictions, the candidate will subscribe to shares and become a cooperative associate. Everybody is free to join and leave the association, and COAPEL also has the right to dismiss a member that is violating its bylaws. Associate shares are transferable to heirs, aiming to maintain farmers as co-op suppliers, but in some cases it is more financially attractive to disassociate due to the appreciation of shares. COAPEL has little control over associates leaving, while some associates remain but in an inactive state.

Members’ participation occurs through the General Assembly, the main company council, where big decisions are made and the Board of Directors and Audit Committee members are elected. All members, except the ones with employment relationships, can be elected and voted into COAPEL councils. Council representatives are elected every three years, and one-third of them are allowed reelection. At least two-thirds of the Board of Directors need to be engaged in agricultural activities in order to keep focus on the co-op’s core business and generate more understanding of associates’ needs and feelings regarding issues such as raw material price changes. The main members of this supply chain are milk farmers. The co-op only buys raw materials directly from producers that are associates. COAPEL undertakes to buy all associates’ production, and associates are not allowed to sell this production to other companies (although COAPEL has little control over this). The associates have a huge range of benefits given by the co-op, and if they divert production, the co-op can charge them the amount of investments made in their land. Most of these farmers own a small amount of land, producing less than 18,000 liters of milk every day. In particular, 55% of the farmers lie in that production range and comprise 19% of total production, 36% produce between 18,000 and 100,000 liters per day and comprise 48% of total production, and the remaining 9% produce more than 100,000 liters daily and comprise 33% of total production (COAPEL 2010).

Supply Chain Analysis Based on a Transaction Costs Approach

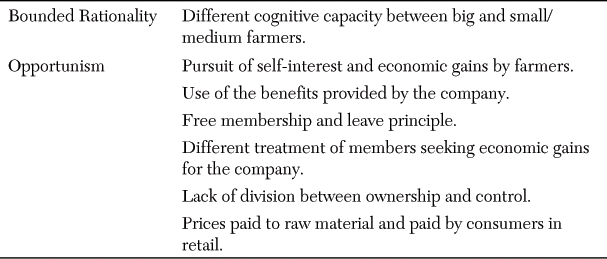

After the consulting team analyzed the relationships and management along COAPEL’s supply chain, transactions were analyzed based on transaction costs, divided into two pieces: behavioral assumptions and dimensional assumptions.

Within bounded rationality were found differences in cognitive abilities between large versus small farmers. Larger farmers have their rationality expanded, due to greater access to education and information and a better relationship with the company, community, and other farmers. These factors generate more subsidies to them in decision making and, consequently, result in further development of their properties. Small farmers tend to have less access to education and information along with restricted relationships with other members and the community, as well as range of cultural and social barriers. These cognitive capacity differences were visible in the members’ respective council participation, whereby small farmers lack awareness and organizational capacity due to a bigger bounded rationality to make strategic decisions.

Members’ opportunism was once more related to the farmers’ respective sizes. Bigger farmers are less loyal and have weaker ties in relationships with the co-op due to both a greater independence that they have from the co-op to develop their activities and a larger focus on self-interests. This factor was evidenced in dairy farming competition, when associates choose to no longer sell to COAPEL and instead seek greater profits offered by competing companies.

This opportunism also appeared through the use of the co-op’s benefits. Members can improve their lands and improve their production through subsidies and access to low-cost loans given by COAPEL and are free to join and leave the association at any time, which is a cooperative principle, without COAPEL receiving returns on those investments.

Another opportunism factor was evidenced in the dependence of small farmers with COAPEL to help make their activities economically viable. Some dissatisfaction was evident, as production bonuses are given, in general, to large farmers who have greater ability to modernize and invest in their land, impacting directly in volumes and quality of milk. The co-op tries to solve part of this problem through an active approach to small producers, seeking growth and development of their production. Besides, COAPEL faces a dilemma with this issue: it wants to maintain small farmers, even when economically unviable, while needing to retain large farmers, less representative in membership, but more economically profitable for the co-op.

As previously referenced by Batalha (2001), a lack of division between ownership and control of the company was also evident. Although the company is managed by professionals, trying to mitigate this risk, the associates actively influence COAPEL’s councils, directly affecting the management. Thus, there are trends in pursuit of self-interest and seek greater benefits for farmers. Finally, there was clear evidence of huge differences between the price paid to producers and those paid by consumers.

Most assets used in the dairy industrialization process are highly specific and have high monetary value. Also, equipment and machinery used for animal husbandry, as well as the animals themselves, have high value added to production and are quite specific. A dairy cow, for example, has no value or quality in its meat because its genetics result in excellent milk but poor-tasting meat.

Transaction frequency between members of the supply chain occurs on a recurring basis: (1) every two days milk is collected from the farms, (2) end products are manufactured daily, (3) these products are distributed to final clients daily, (4) product sales also occur regularly, depending on stocks and needs of consumers, and (5) technical visits occur more sporadically, depending on farmer requests.

Transaction uncertainties are also strongly related to a lack of contracts for members’ milk supply. The only contracts between COAPEL and its associates are related to financing, which guarantee payments of an associate during the contract period. Thus, there is no certainty of permanence of associates or return on investments made by subsidies given.

Another uncertainty factor is related to the dairy sector that has a high volatility of prices and other external factors such seasonality of production and demand, which directly affects the supply chain activities. The co-op seeks to mitigate these risks through product reserves, maintaining stability of prices paid to its members.

Action Plans

After analyzing COAPEL’s supply chain, the managers promoted a meeting with the council of cooperative members and other key staff members to brainstorm and list some possible action plans to be implemented in the co-op in order to reduce risks and improve the company process as a whole. Whatever actions emerge from this meeting cannot contradict the co-op’s values and principles. Also, all the actions have to be related with each of the transaction costs that come out the analysis as a form of mitigating those problems.

Chopra, S.; Meidl, P., Gerenciamento da Cadeia de Suprimentos: Estratégia, Planejamento e Operação. Prentice Hall: 2003. 465p.

Cooperative. In: Aliança Internacional Cooperativa – International Co-operative Alliance. Retrieve from <http://www.ica.coop/al-ica/>.

Cooperative. In: Organização e Sindicato das Cooperativas do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, 2010. Retrieve from <http://www.ocergs.coop.br/>.

Cristopherson Am, G; Coath, E. Collaboration or Control in Food Supply Chains: Who Ultimately Pays the Price? International conference on chain and network management in agribusiness and the food industry, 2002, Holanda: Wageningen Academic Publishers.

Farina, E. M. Q. apud Zibersztajn, D., Neves, M. F., Organização Industrial no Agribusiness, Pioneira: 2000. pp. 39–60.

Lambert, D. M.; Cooper, M. C, Issues in Supply Chain Management + Industrial Marketing Management. New York: 2000. Vol. 29, pp.65-83.

Yin, R. K., Estudo de Caso: planejamento e métodos. Bookman: 2001. 248p.

Williamson, O. E., The economic Institutions of Capitalism. Free Press: 1987. 450p.

Gusmão, S. L.L., Proposição de Um Esquema Integrando a Teoria das Restrições e a Teoria dos Custos de Transação para Identificação e Análise das Restrições em Cadeia de Suprimentos: estudo de caso na cadeia de vinhos finos do Rio Grande do Sul. Ph. D. Thesis, UFRGS, Escola de Administração: 2004. 222 p.